ABSTRACT

The accurate diagnosis of endometrial cancer (EC) holds great promise for improving its treatment choice and prognosis prediction. This work aimed to identify diagnostic biomarkers for differentiating EC tumors from tumors in other tissues, as well as prognostic signatures for predicting survival in EC patients. We identified 48 tissue-specific markers using a cohort of genome-wide methylation data from three common gynecological tumors and their corresponding normal tissues. A diagnostic classifier was constructed based on these 48 CpG markers that could predict cancerous versus normal tissue with an overall correct rate of 98.3% in the entire repository. Fifteen CpG markers associated with the overall survival (OS) and development of EC were also identified based on the methylation patterns of the EC samples. A prognostic model that aggregated these prognostic CpG markers was established and shown to have a higher discriminative ability to distinguish EC patients with an elevated risk of mortality than the FIGO staging system and several other clinical prognostic variables. This study presents the utility of DNA methylation in identifying biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of EC and will help improve our understanding of the underlying mechanisms involved in the development of EC.

KEYWORDS: Endometrial cancer, diagnostic marker, DNA methylation, overall survival, prognostic marker

Introduction

In recent years, gynecologic cancer, including ovarian cancer (OC), endometrial cancer (EC), cervical cancer (CC), vaginal cancer, and vulvar cancer, has become the third leading cause of death for women worldwide. Among them, EC is the most commonly diagnosed gynecological cancer in developed countries, accounting for approximately 7% of new cancer cases in women [1]. Currently, FIGO staging – determined by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics –, together with histological classification are the main factors used for EC patient stratification. The diagnosis of EC is generally based on histological subtype [2] and other markers identified via histology and immunohistochemistry. Accurate diagnosis is crucial when choosing the proper treatment and predicting survival [3]. However, complex anatomy may influence the accurate identification of the tissue of origin or tumor type. In addition, the acquisition of low-quality biopsy specimens may also increase the diagnostic uncertainty. Therefore, the improvement of diagnostic certainty is urgent. At present, molecular characterization is increasingly applied to predict cancer prognoses and responses to therapy. In addition, candidate biomarker studies have consistently identified many specific molecular alterations in EC, including mutations, DNA methylation, microsatellite instability, copy number alterations, and gene expression patterns [4–8].

Gene promoter DNA methylation, an epigenetic regulator of gene expression that usually results in gene silencing [9], is a crucial factor in cancer progression. Although DNA methylation is highly cell specific, some changes in methylation are reproducibly found in nearly all cases of a specific type of cancer [3]. Therefore, DNA methylation could be used as a biomarker of cell types to distinguish ambiguous tissues and infer underlying cell type proportions [10]. Due to its early occurrence in carcinogenesis and its stability and detectability using highly sensitive and specific assays [8], DNA methylation has rapidly gained clinical attention as a biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of malignant carcinomas such as lung cancer [11,12]. Although methylation studies in EC are still preclinical, the understanding of DNA methylation associated with the EC phenotype continues to rapidly improve [13] as genome-wide technologies continue to develop, such as the Infinium HumanMethylation27 array and HumanMethylation450 array.

Other types of tissues, such as cervix, are inevitably mixed with our tissue of interest in the process of clinical diagnostic sampling. Therefore, in this study, we focused on the accurate diagnosis of EC, as well as in the differentiation of EC from other gynecological cancers. We analyzed genome-wide methylation profiles from three common gynecological tumors and their corresponding normal tissues to identify tissue-specific methylation markers. A diagnostic classifier was subsequently constructed to distinguish the presence of a malignancy as well as its tissue of origin. Additionally, we identified prognostic methylation markers of EC based on DNA methylation patterns and constructed a prognostic model to predict survival of EC patients.

Materials and methods

Data sources and data processing

As shown in Supplementary Table S1, HumanMethylation450 array data and the corresponding clinical information from a total of 1303 tissue samples, including three common gynecological tumors (n = 576 for primary CC tumors; n = 464 for primary EC tumors; n = 185 for primary OC tumors) and their corresponding normal tissue samples (n = 22 for normal cervix tissues; n = 46 for normal uterine tissues; n = 10 for normal ovary tissues), were retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) database (https://icgc.org/). Among these samples, the CC group was mainly composed of squamous cell carcinoma and most of the OC group were serous cystadenocarcinomas. The EC group mainly included endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma and serous endometrial adenocarcinoma (Supplementary Table S2). Among the EC group samples, the EC cohort (n = 422 for primary EC tumors, Supplementary Table S3) from TCGA database was used for the identification of prognostic markers and the construction of the prognostic model. The entire cohort was used for the identification of tissue-specific markers and the construction of the diagnostic classifier. The expression profiling cohort of EC (n = 422 for primary EC tumors) was also downloaded from the TCGA database. Normalization of beta values from the methylation data was performed using the background normalization method. Beta values for any markers that did not exist across all 1303 samples were excluded.

Identification of tissue-specific CpG markers

COHCAP, an accurate unique tool for single-nucleotide resolution DNA methylation analysis [14], can determine regions showing differential methylation and has been shown to meet or exceed the accuracy of all the other algorithms in previous studies [15]. Therefore, COHCAP was used to identify the differential methylation of CpG sites with FDR <0.05 and delta-beta >0.3. Considering the possibility of mixed tissues, we not only compared EC with normal uterine tissue but also with other two gynecologic cancers in order to exclude the non-specific CpG sites and improve the specificity of the markers for EC. Therefore, each type (CC, EC, OC, and their corresponding normal tissues) was compared against all other five types of samples to identify tissue-specific signatures. For each of the six types of tissue, the entire cohort was randomly split into training and testing cohorts at a 2:1 ratio (Supplementary Table S4). The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), a variable selection method suitable for high-dimensionality on the prescreened training cohort, was implemented in R language (glmnet package) and used for variable selection. The tuning parameters were determined according to the expected generalization error estimated from 10-fold cross-validation. As the results can strongly depend on the arbitrary choice of a random sample split for sparse high-dimensional data, we adopted the ‘multi-split’ method [16], a remedy to improve variable selection consistency while controlling finite sample error. We repeated the ‘randomly split-screen-selection’ procedure 10 times and ended up with 10 different sets of candidate sites. These sites were then aggregated into the most common ones and subjected to the next round of LASSO analysis for the identification of tissue-specific markers.

Construction and evaluation of the diagnostic classifier

Unsupervised hierarchal clustering according to the methylation pattern of these tissue-specific markers was performed using the pheatmap package in R language. The construction of the diagnostic classifier based on the panel of tissue-specific CpG markers was conducted by performing LASSO under a multinomial distribution. The confusion matrix and receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were provided to further evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic classifier in addition to prediction accuracy.

Identification of prognostic CpG markers in EC

The entire cohort of 422 EC samples was randomly split into training (n = 281) and testing (n = 141) cohorts at a 2:1 ratio (Supplementary Table S4). Univariate Cox regression analysis, a univariate pre-screening procedure, was performed on the training cohort to remove excessive noise and accelerate the computational procedure, which was generally conducted prior to applying any variable selection method [17]. Due to the limitations of the Cox model with high-dimensional data when the sample-size-to-variables ratio is too low (such as <10:1) [18], a Cox model regularized by LASSO penalty was conducted in Coxnet package for further variable selection. The optimal step was determined by the expected generalization error estimated from 10-fold cross-validation. Just as in the aforementioned procedure, we repeated the ‘randomly split-screen-selection’ procedure 10 times to ensure the stability of the variable selection procedure. In addition, the prognostic markers were ultimately identified by performing Coxnet based on the most common markers present in these sets of candidate sites.

Construction and evaluation of the prognostic model of EC

Using the training cohort of EC patients, the prognostic model was constructed by fitting the regularized Cox regression model using markers selected at the optimal step as the covariates. The predictability of the model was evaluated by two criteria: the proportion of explained randomness [19], calculated from the training cohort, and the C-index [20], computed from the test cohort. For the prognostic model, the survival risk score for each patient was calculated by summing the product of the methylation level of a marker and its corresponding regression coefficient. For the model proposed by O’Mara et al., the prognostic score for each patient (used for plotting ROC curve in Supplementary Figure S3A) was calculated using the panel of nine gene signature (PDLIM1, FBP1, NLRC3, ST6GALNAC1, C4BPA, PPP2R3A, TRIM46, EPH2, and PRRG1), as previously described [21]. The ROC curve was plotted for 5-year OS prediction to estimate the sensitivity and specificity of the prognostic model. The optimal cut-off risk score was obtained based on the maximum Youden index in the ROC curve and was used to stratify patients into distinct prognostic groups. Non-parametric (Kaplan-Meier) and semi-parametric (Cox proportional hazards regression prediction) curves were used to analyze the correlations between variables and OS. Hazard ratio (HR) and P values were calculated to compare survival curves by using the ‘survdiff’ function in R language. Wilcoxon rank sum test implemented in survcomp package was employed to compare any two integrated areas under the curves (IAUC) through the results of time dependent ROC curves at some points in time.

Co-expression and functional enrichment analyses of prognostic markers

The correlations between the methylation levels of the prognostic markers and the expression levels of regulated genes were calculated by Spearman’s correlation test. The co-expression relationships between the genes were computed by Pearson’s correlation test. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses of the co-expressed genes were performed using the clusterProfiler package [22]. Hypergeometric testing was used as the statistical method, while whole human genes were used as background genes. Only the top 35 pathways with a P value threshold of <0.05 were shown and considered to be significantly enriched functional categories.

Results

Identification of the tissue-specific methylation markers

The entire cohort, comprised of CC (n = 576), EC (n = 464), OC (n = 185) and their corresponding normal tissue samples, was incorporated in this analysis (Supplementary Table S1). By performing differential methylation analyses, a list of tissue-specific methylation sites for six types of tissues was obtained. Subsequently, the number of these markers was narrowed down to select optimal signatures by using LASSO. Repeated calculations based on 10 training cohorts (randomly partitioned cohorts) were performed continuously to stabilize the variable selection procedure. As a result, 10 sets of candidate sites (average: 96.4, minimum: 84, maximum: 117) were identified from these 10 training cohorts.

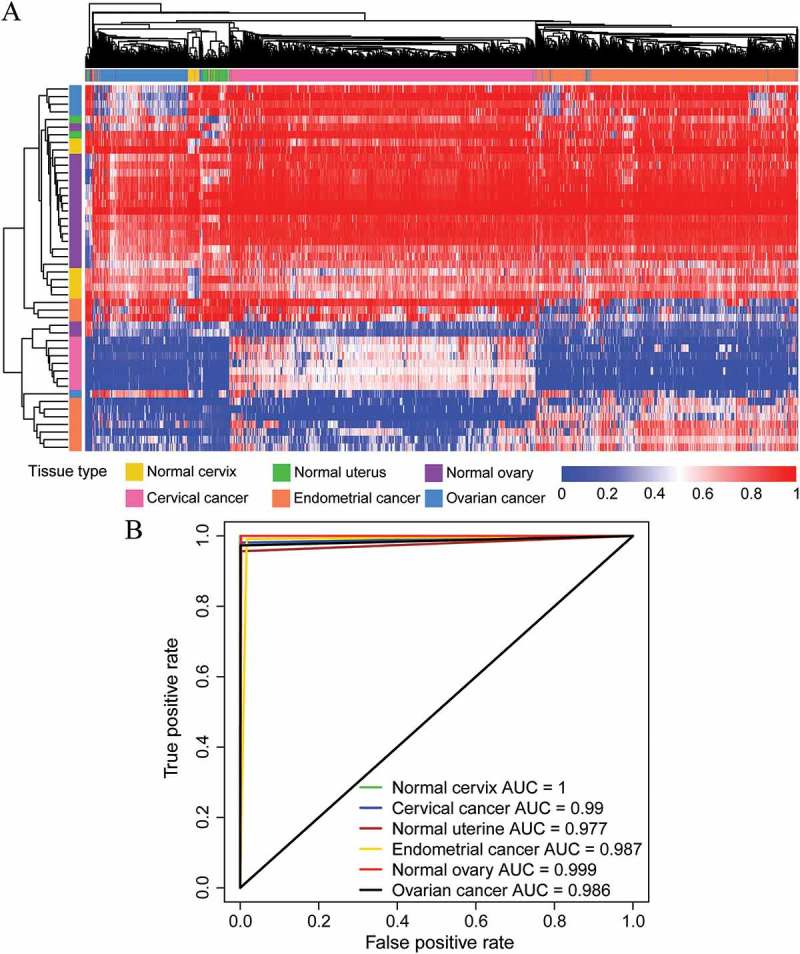

Based on the candidates present in at least 7 out of 10 sets, a panel of 48 CpG sites was ultimately selected as tissue-specific methylation markers for these six types of tissues (Supplementary Table S5). Unsupervised hierarchal clustering of entire cohort samples according to the methylation pattern of these tissue-specific markers was performed, and the heatmap showed that most of the same types of tissues clustered together apart from a few exceptions (Figure 1(a)). Similarly, the relatively obvious discrimination between cancer and normal tissue was also observed when cohorts were stratified by cervix, uterus, and ovary (Supplementary Figure S1). These results reveal that these methylation markers might be used to distinguish the three types of cancer tissue, as well as to differentiate cancer tissue from normal tissue.

Figure 1.

Performance of the DNA methylation diagnostic classifier in tissue prediction using the entire cohort. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and heatmap of the entire cohort based on the methylation patterns of the tissue-specific markers selected. (B) ROC curves were generated to predict the six types of cancerous and normal tissues.

Construction of a diagnostic classifier based on tissue-specific markers

A multiclass prediction system (diagnostic classifier) was constructed based on this panel of tissue-specific markers to predict the group membership of the tissue samples (Supplementary Table S6). When using this diagnostic classifier, the overall correct diagnosis rates in the training and testing cohorts were 99.1% and 96.8%, respectively (Table 1). And an overall correct rate of 98.3% was observed when this diagnostic classifier was applied to the entire cohort (Table 1). Remarkably, no false-positive case was found in the entire cohort, suggesting the high prediction accuracy of this classifier. The ROC curves for various tissue predictions were plotted to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of this classifier (Figure 1(b)), and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) of each tissue was consistently higher than 0.97. Taken together, these results demonstrate the robustness of these methylation patterns in identifying the presence of a malignancy, as well as its tissue site of origin.

Table 1.

Confusion table of the training, testing and entire cohorts.

| Cervical cancer | Endometrial cancer | Ovarian cancer | Normal cervix | Normal uterus | Normal ovary | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical cancer | 0.990, 0.964, 0.981 | 0.000, 0.006, 0.002 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | |

| Endometrial cancer | 0.010, 0.031, 0.017 | 0.997, 0.981, 0.991 | 0.016, 0.032, 0.022 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | |

| Ovarian cancer | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.006, 0.002 | 0.976, 0.968, 0.973 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | |

| Normal cervix | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 1.000, 1.000, 1.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | |

| Normal uterus | 0.000, 0.005, 0.002 | 0.003, 0.000, 0.002 | 0.008, 0.000, 0.005 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 1.000, 0.867, 0.957 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | |

| Normal ovary | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.006, 0.002 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.133, 0.043 | 1.000, 1.000, 1.000 | |

| False-negative | 0.000, 0.005, 0.002 | 0.003, 0.006, 0.004 | 0.008, 0.000, 0.005 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.002, 0.005, 0.003 |

| False-positive | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 |

| Wrong tissue | 0.010, 0.031, 0.017 | 0.000, 0.013, 0.004 | 0.016, 0.032, 0.022 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.000, 0.133, 0.043 | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000 | 0.007, 0.028, 0.014 |

| Correct | 0.990, 0.964, 0.981 | 0.997, 0.981, 0.991 | 0.976, 0.968, 0.973 | 1.000, 1.000, 1.000 | 1.000, 0.867, 0.957 | 1.000, 1.000, 1.000 | 0.991, 0.968, 0.983 |

The rows represent the predictions and the columns represent the true values. The values of the table indicate the proportion of the predicted number of a cancer type (represented by the row) in overall samples of the cancer type (represented by the column) in training, testing and entire cohorts, repectively. False-negative represents the cancer samples were misclassified as normal samples. False-positive represents the normal samples were misclassified as cancer samples. Wrong tissue represents the misclassified types of cancer or normal samples.

Identification of prognostic methylation markers in EC

In this section, we explored the prognostic utility of a methylation signature in EC. Using the training data, CpG sites associated with OS were identified by fitting univariate Cox proportional hazard regression models with P values <0.05. Meanwhile, only significantly differentially methylated sites between EC and normal uterine tissues were considered for further analysis. As a result, an average of 881 (min.: 557, max.: 1135) OS-related CpG sites was retained in 10 randomly generated training cohorts. By fitting the Cox model regularized by LASSO penalty, 10 sets of candidate sites (avg.: 27, min.: 6, max.: 56) were identified from these 10 training cohorts. A panel of 15 sites was finally selected as methylation markers using Coxnet based on the candidates present in at least 3 out of 10 groups.

Construction of a methylation prognostic model for predicting OS in EC

Subsequently, the DNA methylation levels of the 15 methylation markers in a newly generated training cohort was used to construct a survival risk score system (prognostic model) and, thus, the regression coefficient for each CpG was obtained (Table 2). On average, the proportion of explained randomness calculated from the training data was 0.78 (min.: 0.72, max.: 0.82) and the average C-index calculated from the test data was 0.83 (min.: 0.78, max.: 0.88), indicating the good predictability of these methylation signatures.

Table 2.

Fifteen methylation markers included in the prognostic model of EC.

| Methylation marker | Coefficient | Chromosome location | Gene name | Methylation level association with poor prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg00143527 | 1.50 | Chr15: 81,292,171 | MESDC1 | High |

| cg20072442 | −0.03 | Chr2: 80,530,255 | LRRTM1 | Low |

| cg22032364 | 1.26 | Chr13: 26,112,093 | ATP8A2 | High |

| cg00463767 | 1.71 | Chr2: 63,282,043 | OTX1 | High |

| cg22912497 | −1.55 | Chr19: 38,974,117 | RYR1 | Low |

| cg04385765 | −0.11 | Chr7: 5,122,887 | - | Low |

| cg19832521 | −0.37 | Chr14: 27,065,974 | NOVA1 | Low |

| cg11793269 | 2.72 | Chr5: 2,752,545 | C5orf38; IRX2 | High |

| cg14537713 | −0.97 | Chr6: 27,258,466 | - | Low |

| cg14359824 | −0.72 | Chr9: 72,435,533 | C9orf135 | Low |

| cg21233675 | 1.81 | Chr12: 66,122,497 | - | High |

| cg05165559 | 0.78 | Chr20: 62,037,758 | KCNQ2 | High |

| cg26697065 | −1.20 | Chr16: 30,456,379 | SEPHS2 | Low |

| cg01750724 | −1.15 | Chr8: 1,570,635 | DLGAP2 | Low |

| cg03241649 | −1.14 | Chr19: 44,405,924 | - | Low |

In detail, the survival risk score was calculated based on the following formula: Risk score = [1.50 × beta value (BV) of cg00143527] + (−0.03 × BV of cg20072442) + (1.26 × BV of cg22032364) + (1.71 × BV of cg00463767) + (−1.55 × BV of cg22912497) + (−0.11 × BV of cg04385765) + (−0.37 × BV of cg19832521) + (2.72 × BV of cg11793269) + (−0.97 × BV of cg14537713) + (−0.72 × BV of cg14359824) + (1.81 × BV of cg21233675) + (0.78 × BV of cg05165559) + (−1.20 × BV of cg26697065) + (−1.15 × BV of cg01750724) + (−1.14 × BV of cg03241649). Based on the formula above, a higher score indicates an increased risk of mortality, whereas a lower score denotes a better outcome. Based on the BV of these 15 markers in the training cohort, survival risk scores were calculated for each patient. In addition, the 281 patients were partitioned into two groups according to the median of risk score. The Kaplan-Meier curve for these two groups was plotted, which demonstrated a significant difference between the OS for patients in Group 1 and Group 2 (P <0.001, Supplementary Figure S2A). The analogous situation was observed for the test cohort P <0.001, Supplementary Figure S2B). These findings indicate that the methylation prognostic model might be used to predict the OS for EC patients.

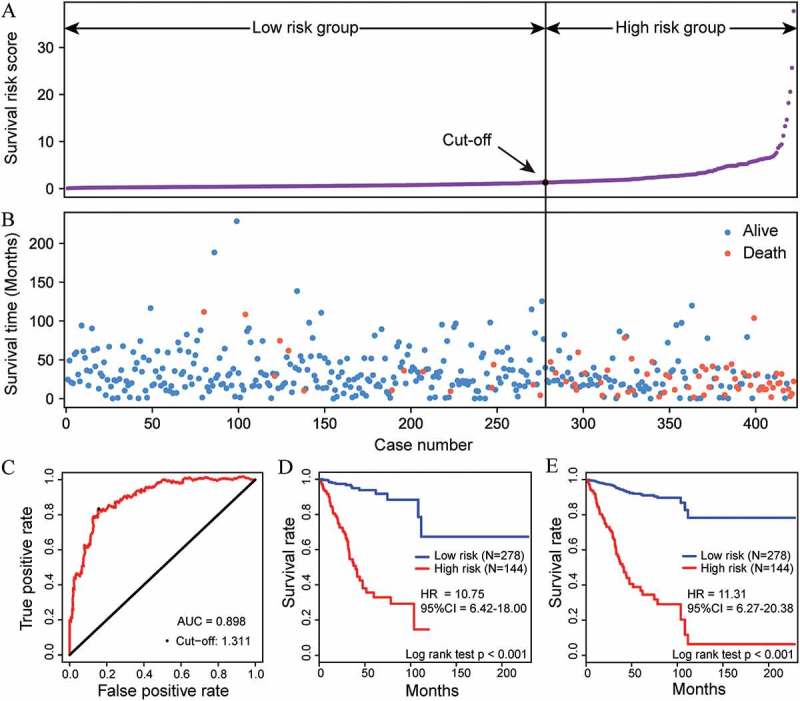

Performance evaluation of the methylation prognostic model

For entire EC cohort (n = 422), the risk score of EC patients ranged from 0.072 to 37.733 (Figure 2(a,b)). The time-dependent ROC curve for 5-year OS prediction was plotted with an AUC of 0.898 (Figure 2(c)), confirming the ability of this methylation model to predict prognosis in EC patients. The patients were divided into 2 risk groups (Figure 2(a,b)) based on the optimal cut-off risk score (1.311, Figure 2(c)) determined by the maximum Youden index in the ROC curve. More specifically, 278 (65.88%) patients were classified into the high-risk group, whereas the remaining 144 (34.12%) patients were categorized into the low-risk group. It is noteworthy that there was a significant difference in the number of deaths between these two groups (40.28% in high-risk vs. 5.04% in low-risk, P <0.001, Figure 2(b)). A significant difference in the 5-year OS between the 2 risk groups was demonstrated by a Kaplan-Meier curve (HR = 10.75, P <0.001, Figure 2(d)) and a Cox proportional hazards regression prediction curve (HR = 11.31, P <0.001, Figure 2(e)). The high concordance between the non-parametric and semi-parametric prediction curves indicated the possibility of accurately predicting a new patient’s survival status for any future time point using this methylation model.

Figure 2.

Performance of the methylation prognostic model in the OS prediction of patients with EC. The distribution of survival risk score (A) and survival (or censoring) time (B) of EC patients in the entire EC cohort (n = 422). (C) The ROC curve was generated for 5-year OS predictions with an AUC of 0.898. An optimal cut-off value (1.311), shown as a black straight line in A and B, was obtained to divide the patients into low- and high-risk groups. Kaplan-Meier curves (D) and Cox proportional hazards regression prediction curves (E) were plotted to analyze the correlations between this model and OS, respectively. Patients in the high-risk group exhibited a poorer OS than patients in the low-risk group (all P <0.001).

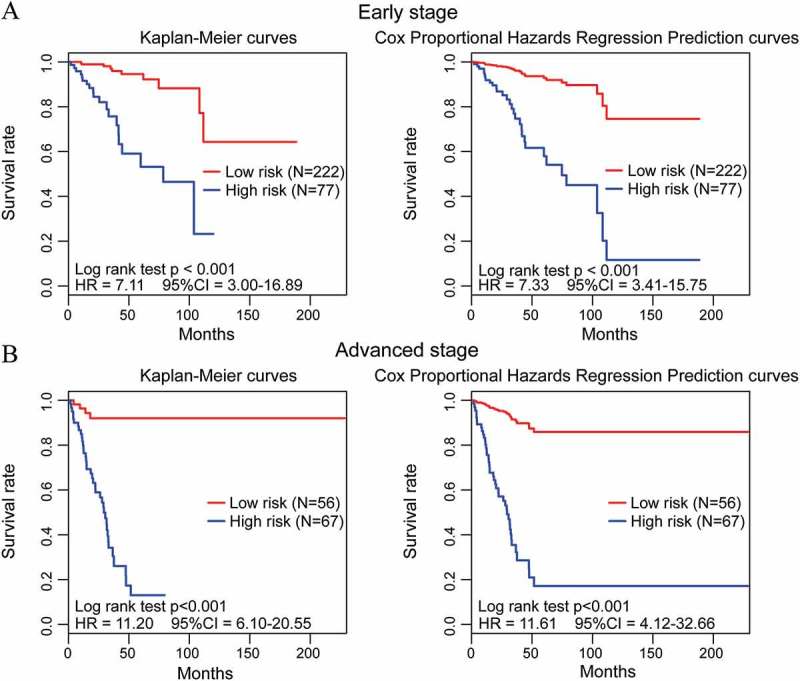

FIGO stage and histological type correlate with the prognosis of EC and are very important markers in achieving optimal treatment outcomes. Therefore, several clinical variables potentially associated with prognosis, including age, FIGO stage, histological type, and histologic grade, together with this methylation model, were included in univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses using entire and test EC cohorts (Table 3), which indicated the relatively high prognostic ability of this methylation model in predicting OS of EC patients (all P <0.001). These findings suggest that this model might be an independent classifier for prognostic predictions of EC patients. Additionally, survival analysis was further performed to evaluate the effectiveness of the prognostic model in subsets of patients with the clinical variables mentioned above. When stratified by these variables, our model also displayed a clinical and statistical significance (all P <0.001, Table 4). For instance, EC patients in the same FIGO stage [early stage (I/II stage in Figure 3(a)) and advanced stage (III/IV stage in Figure 3(b)) could be successfully separated into high-risk and low-risk subgroups by plotting both Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards regression prediction curves (all P <0.001, Figure 3).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses of potential prognostic variables for EC patients.

| Variables | Entire EC cohort |

Test EC cohort |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Univariable analysis | |||||

| Age | >60 vs. ≤60 | 2.27 (1.25–4.15) | 0.007 | 2.18 (0.46–0.73) | 0.16 |

| FIGO stage | Advanced stage vs. Early stage | 4.55 (2.83–7.31) | ###### | 4.89 (2.04–11.68) | ###### |

| Histologic grade | G3 vs. G1/G2 | 3.61 (1.85–7.05) | ###### | 5.16 (1.20–22.19) | 0.03 |

| Histological type | MSE vs. EEA | 2.36 (0.92–6.04) | 0.07 | 5.50 (1.45–20.83) | 0.01 |

| SEA vs. EEA | 3.13 (1.93–5.08) | ###### | 5.14 (2.00–13.24) | ###### | |

| Methylation model | High risk vs. low risk | 11.31 (6.27–20.38) | ###### | 18.00 (6.00–54.00) | ###### |

| Multivariable analysis | |||||

| Age | >60 vs. ≤60 | 1.41 (0.75–2.63) | 0.28 | 0.78 (0.22–2.77) | 0.70 |

| FIGO stage | Advanced stage vs. Early stage | 3.13 (1.90–5.18) | ###### | 5.31 (1.78–15.89) | ###### |

| Histologic grade | G3 vs. G1/G2 | 1.37 (0.64–2.90) | ###### | 2.18 (0.43–10.99) | 0.34 |

| Histological type | MSE vs. EEA | 1.04 (0.39–2.76) | 0.94 | 1.82 (0.38–8.66) | 0.45 |

| SEA vs. EEA | 0.76 (0.43–1.35) | 0.35 | 0.41 (0.10–1.63) | 0.20 | |

| Methylation model | High risk vs. low risk | 8.78 (4.55–16.95) | ###### | 22.41 (5.58–89.98) | ###### |

Advanced stage: I/II stage; Early stage: III/IV stage; EEA: Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma; MSE: Mixed serous and endometrioid; SEA: Serous endometrial adenocarcinoma.

Table 4.

Stratification analysis of the methylation prognostic model.

| Subgroup | Entire EC cohort |

Test EC cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | HR (95% CI) | P value | No. of Patients | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤60 | 132 | 16.90 (3.90–73.20) | 3.58E-09 | 45 | Inf | 7.09E-08 |

| >60 | 290 | 8.32 (4.86–14.24) | 1.92E-14 | 96 | 8.97 (3.06–26.32) | 2.82E-06 |

| FIGO stage | ||||||

| Early stage | 299 | 7.11 (3.00–16.89) | 2.70E-09 | 103 | 8.37 (1.60–43.84) | 2.56E-04 |

| Advanced stage | 123 | 11.20 (6.10–20.55) | 5.07E-09 | 38 | 19.68 (6.05–64.02) | 4.50E-05 |

| Histological type | ||||||

| EEA | 303 | 9.80 (4.15–23.12) | 8.33E-15 | 104 | 8.90 (0.89–88.70) | 1.63E-04 |

| SEA | 98 | 6.16 (3.03–12.53) | 5.46E-04 | 29 | Inf | 7.09E-03 |

| MSE | 21 | 14.03 (0.72–272.79) | 7.24E-05 | 8 | Inf | 4.31E-02 |

| Histologic grade | ||||||

| G1/G2 | 151 | 13.04 (1.70–100.08) | 1.84E-07 | 52 | 13.67 (0.06–3338.65) | 1.18E-02 |

| G3 | 271 | 8.39 (5.03–14.00) | 1.06E-13 | 89 | 15.15 (5.44–42.22) | 5.92E-09 |

Advanced stage: I/II stage; Early stage: III/IV stage; EEA: Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma; MSE: Mixed serous and endometrioid; SEA: Serous endometrial adenocarcinoma.

Figure 3.

Performance of the methylation prognostic model in the OS prediction of EC patients stratified by FIGO stage. (A, B) EC patients with early (FIGO I/II stage) and advanced stage (FIGO III/IV stage) were divided into high- and low-risk groups based on their cut-off value, respectively. By plotting Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards regression prediction curves, the prognostic model capability for OS prediction of EC patients with early stage (A) and advanced stage (B) was assessed individually.

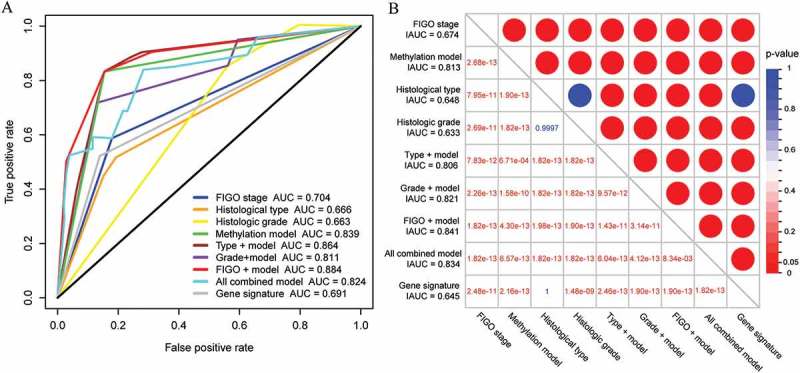

Subsequently, ROC curve analysis was performed to compare the sensitivity and specificity in OS prediction among these different prognostic variables (Figure 4(a)). Here, we assumed that a larger AUC value of ROC curves implies a better model for prediction [23]. As shown in Figure 4(b), the IAUC value of the methylation prognostic model was significantly higher than that of the FIGO stage, histological type, and histologic grade (all <0.001). These findings further demonstrate that this model is a novel prognostic marker with better predictive ability than other clinical variables. Remarkably, a combined model comprised of the methylation model and FIGO stage (Figure 4(a,b)) had a larger AUC than those of the prognostic factors alone and other forms of combined models, suggesting that our model might be used to assist prognosis predictions for EC patients. In addition, a nine-gene signature proposed by O’Mara et al. [21] was also included in this analysis (Figure 4), which demonstrated its ability to predict the prognosis for EC (Supplementary Figure S3). By comparison, our model exhibited a significantly increased IAUC value (P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the survival prediction power of the potential prognostic variables for EC. (A) The time-dependent ROC curves for the 5-year OS prediction of the potential prognostic variables. (B) Comparison of the integrated areas under the ROC curves of the potential prognostic variables for EC. The entry values of the table represent the P values calculated from the Wilcoxon rank sum test for the comparison between larger IAUC and smaller IAUC.

Characterization and functional analysis of the prognostic methylation markers

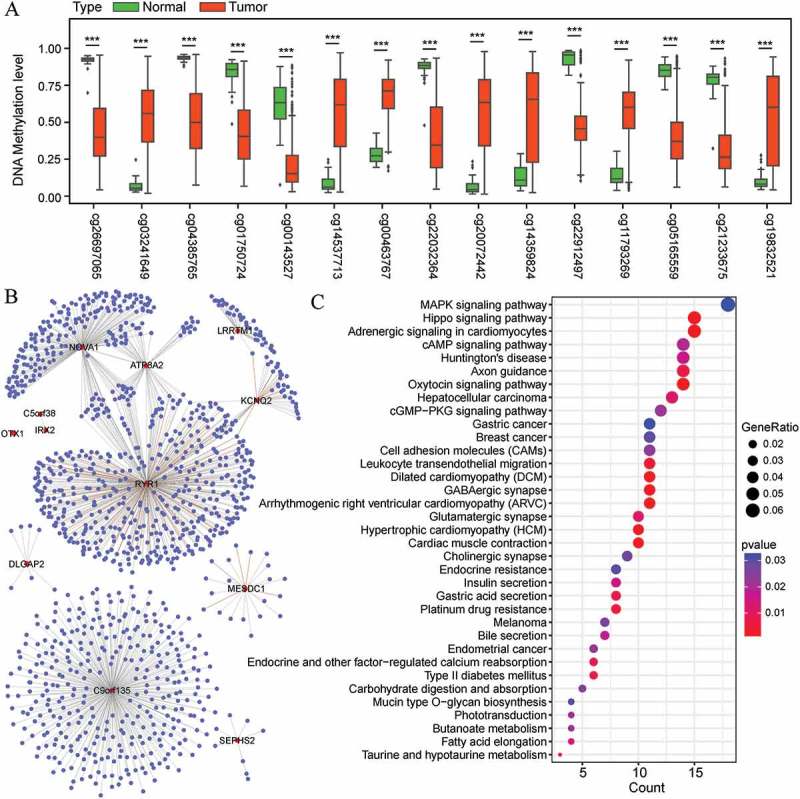

As for the characteristics of these methylation markers, higher methylation levels of the six markers were associated with shorter OS (coefficient >0) whereas higher methylation levels of the remaining nine markers were related to longer OS (coefficient <0, Table 2). A comparison of the DNA methylation levels of these 15 prognostic marker sites between EC and normal uterine tissues was conducted using the EC subset (n = 464 for primary EC tumors and n = 46 for normal uterine tissues) of the full cohort. Remarkably, the methylation level of eight markers were significantly downregulated in the 464 EC samples compared with the 46 normal uterine tissues (all FDR <0.001, Figure 5(a)). In contrast, the methylation level of the remaining seven markers were upregulated in EC tissues (all FDR <0.001, Figure 5(a)). These findings suggest that these 15 selected markers may be not only associated with prognosis of EC but also involved in the development of EC.

Figure 5.

Differential methylation analysis of 15 selected markers and the co-expression analysis of their regulated genes. (A) DNA methylation levels of the 15 markers in 464 EC tissues and 46 normal uterine tissues. The distributions of the methylation level data are represented by box plots and the FDRs were calculated by COHCAP. (***FDR <0.001) (B) Cytoscape visualization of the co-expression of the 12 genes regulated by the 15 methylation markers with other genes (Pearson’s correlation coefficient >0.40) (C) Functional enrichment of the co-expressed genes in EC with the 12 annotated genes.

The relationship between the 15 selected markers and their regulated genes was annotated (Table 2) and subsequently analyzed using the EC cohort (n = 422) and its corresponding gene expression profiling cohort (n = 422). Based on Spearman’s correlation tests, the correlation between methylation level and gene expression was significantly inversed for MESDC1 (P = 2.38E-06), LRRTM1 (P = 1.65E-07), NOVA1 (P = 1.06E-51), C5orf38 (P = 1.33E-11), IRX2 (P = 4.92E-10), C9orf135 (P = 9.10E-08), and SEPHS2 (P = 4.55E-16), and significantly positive for ATP8A2 (P = 1.50E-21), OTX1 (P = 9.21E-23), RYR1 (P = 0.012), KCNQ2 (P = 5.04E-09), and DLGAP2 (P = 6.76E-10).

To further investigate the potential biological roles of the genes regulated by the 15 methylation markers, the co-expression relationships between these twelve genes and all genes in the EC expression dataset were evaluated. A co-expression network was further constructed based on the Pearson’s correlation coefficients (>0.40, Figure 5(b)), and the expression of 1148 genes was highly correlated with that of at least one of the twelve genes. Subsequently, these co-expressed genes were included in KEGG enrichment analyses. The top 35 significantly enriched pathways (P <0.05) are shown in Figure 5(c). In detail, these genes are associated with various signaling pathways, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, hippo signaling pathway, and oxytocin signaling pathway, as well as several pathways involved in cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma, endometrial cancer, and breast cancer (Figure 5(C)).

Discussion

This study demonstrates the utilization of a series of methylation signatures to identify cancer tissue of origin. Although we focused on the diagnosis of EC here, we also included other two common gynecologic tumors (and their corresponding normal tissues) in the identification of tissue-specific methylation markers to improve the specificity of our diagnostic classifier in these common gynecological cancers. After multiple screening, a panel of 48 tissue-specific markers was ultimately identified, which could distinguish the origins of these three cancers as well as differentiate them from their corresponding normal tissues. A diagnostic classifier was subsequently constructed based on this panel of tissue-specific markers, followed by performance evaluations using fusion tables and ROC curves, which demonstrated the accuracy and effectiveness of this classifier in the diagnosis of EC as well as two other gynecological tumors.

Beyond that, we also utilized methylation signatures to predict prognosis in EC patients. By performing multiple screening procedures, 15 CpG sites were selected as methylation markers that may be not only associated with the prognosis of EC but also involved in the development of EC. Twelve genes, including MESDC1, LRRTM1, NOVA1, C5orf38, IRX2, C9orf135, SEPHS2, ATP8A2, OTX1, RYR1, KCNQ2, and DLGAP2, that corresponded to the selected CpG markers were determined via annotation and correlation analyses. It is noteworthy that some of these genes have been reported in previous studies associated with cancer. For example, MESDC1 is thought to have an oncogenic function in human bladder cancer [24]. C5orf38 and IRX2 may be closely implicated in the carcinogenesis of intestinal type gastric carcinomas [25]. OTX1 is involved in human colon carcinogenesis and may serve as a potential therapeutic target for human colorectal cancer [26]. To further investigate the potential biological roles of the genes regulated by these 15 methylation markers, we constructed a co-expression network comprising these 12 genes and their 1148 highly correlated genes. Functional enrichment analysis showed that these genes were enriched in several pathways in cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma, endometrial cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, and gastric cancer. Moreover, a significant enrichment of these genes in various signaling pathways, such as the MAPK signaling pathway, hippo signaling pathway, oxytocin signaling pathway, and cell adhesion molecule pathways, was also observed. Oxytocin may play a regulatory role in tumor growth [27], and the presence of the oxytocin receptor in endometrial cancer cells represents a key factor in endometrial cancer progression [28]. The Ras-activated MAPK signaling pathway has been well studied [29] and is known to regulate the transcription of genes that are important in the cell cycle [30]. The hippo pathway plays a key role in regulating organ size and tumorigenesis by inhibiting cell proliferation, promoting apoptosis, and regulating stem/progenitor cell expansion [31], which represent potential therapeutic targets in diseases such as degeneration and cancer [32]. Cell adhesion molecules play an important role during the progression of a wide variety of human diseases including cancer. Through their adhesive activities and their dialogue with the cytoskeleton, adhesion molecules directly influence the invasive and metastatic behavior of tumor cells and, by their signaling function, they can be involved in the initiation of tumorigenesis [33]. A prognostic model was ultimately constructed based on these 15 selected CpG markers and further evaluated by plotting ROC curves and non-parametric and semi-parametric prediction curves of OS prediction, confirming the ability of this methylation model to predict prognosis in EC patients.

Notably, histological typing correlates not only with prognosis but also with molecular alterations, expression, and methylation profiles in each tumor type [5,34]. Nevertheless, there is some overlap between different types of EC, both morphologically and molecularly, as noted by the distribution of several genetic alterations described earlier [13]. Moreover, the limitation of histological classification in prognostic predictions has been demonstrated in clinical practice [35]. Therefore, the various histological types of these three gynecologic tumors (e.g., endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma, and serous endometrial adenocarcinoma in EC) were all included in this work to construct a robust model that would be applicable for each type of EC. It is worth noting that mutation profile and clinical outcome of mixed endometrioid-serous endometrial carcinomas are different from that of pure endometrioid or serous carcinomas [36]. Therefore, the mixed endometrioid-serous endometrial carcinoma was included in the analyses.

Further evaluation procedure was conducted using the entire and test EC cohorts; the prognostic model was demonstrated to be an independent prognostic factor capable of predicting OS of EC patients. Additionally, a comparison of the survival prediction power of this model with those of other clinical prognostic variables as well as a nine-gene signature was also performed, further demonstrating that our model is a novel prognostic marker with higher accuracy that might be used to assist in prognosis prediction for EC patients.

Several studies have proposed a series of novel candidate prognostic or diagnostic markers in EC based on gene expression profiles [21,37,38] and protein assays [35] that mainly depended on fresh-frozen specimens. Some biomarkers previously identified usually contained only a single marker [39,40] or several markers [37,38] that lacked risk score formulas or biomarker coefficients, which restricted the widespread use of these biomarkers in clinical practice. Integrating multiple biomarkers into a single model would substantially improve prognostic value compared with a single biomarker alone [41]. Here, we not only identified methylation biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of EC but also constructed two models with specific marker coefficients, which make this system both efficient and convenient for clinical application. Notably, methylation experimentation requires only a small amount of tissue to obtain adequate DNA, thus potentially allowing the use of lower-quality biopsies, such as formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material. Therefore, this methylation classifier can also be efficiently applied to the identification of EC in cases without adequate tissue yields or quality for histological diagnosis, which requires the preservation of the tissue architecture. Compared with other methylation profile analyses used in the diagnosis of EC [8], our models were established based on the HumanMethylation450 array data that includes wider CpG site coverage. Although our diagnostic classifier contains more methylation markers, it has a high discriminative ability to distinguish not only three gynecological cancers but also their corresponding normal tissues.

The limited available data about EC and two other gynecological cancers (CC and OC) impose some limitations to this study that should be acknowledged. First, due to the limited sample amount currently available in the database, especially normal tissue samples, more samples are required to further prove the diagnostic and prognostic values of our models in patients before they are applied in the clinic. Second, only a fraction of human CpG sites were included in the analysis, although array data with wider CpG site coverage (HumanMethylation450) was incorporated into this work. Thus, the markers identified here may not be the best signatures among all CpG candidate sites that are potentially associated with the diagnosis or prognosis of EC. Finally, we lack information on the mechanisms behind the diagnostic and prognostic values of these markers in EC, and experimental studies on these CpG markers will provide valuable information to further enhance the understanding of their functional roles. However, despite these drawbacks, our models exhibited potentially powerful abilities in the diagnosis and prognosis of EC patients.

In summary, we constructed a methylation diagnostic classifier based on 48 tissue-specific markers in three common gynecological cancers that could accurately and effectively identify the presence of a malignancy as well as its site of origin. We also established a robust prognostic model aggregating 15 CpG markers that can be used to efficiently assist in prognosis prediction for EC patients and may help to guide the application of rational therapy in clinical practice. In addition, this study will help to improve the understanding of the underlying mechanisms involved in the development of EC.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 31670784 and 31370795

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015. March 1;136(5):E359–86. PubMed PMID: 25220842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piulats JM, Guerra E, Gil-Martin M, et al. Molecular approaches for classifying endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2017. April;145(1):200–207. PubMed PMID: 28040204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hao X, Luo H, Krawczyk M, et al. DNA methylation markers for diagnosis and prognosis of common cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. July 11;114(28):7414–7419. PubMed PMID: 28652331; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5514741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang SW, Li J, Podratz K, et al. Application of DNA methylation biomarkers for endometrial cancer management. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2008. September;8(5):607–616. PubMed PMID: 18785809; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5650066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Kandoth C, Schultz N, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013. May 2;497(7447):67–73. PubMed PMID: 23636398; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3704730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou XC, Dowdy SC, Podratz KC, et al. Epigenetic considerations for endometrial cancer prevention, diagnosis and treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2007. October;107(1):143–153. PubMed PMID: 17692907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinde I, Bettegowda C, Wang Y, et al. Evaluation of DNA from the Papanicolaou test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. Sci Transl Med. 2013. January 9;5(167):167ra4 PubMed PMID: 23303603; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3757513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wentzensen N, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Killian JK, et al. Discovery and validation of methylation markers for endometrial cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014. October 15;135(8):1860–1868. PubMed PMID: 24623538; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4126846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaissiere T, Sawan C, Herceg Z.. Epigenetic interplay between histone modifications and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Mutat Res. 2008. Jul-Aug;659(1–2):40–48. PubMed PMID: 18407786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Titus AJ, Gallimore RM, Salas LA, et al. Cell-type deconvolution from DNA methylation: a review of recent applications. Hum Mol Genet. 2017. October 1;26(R2):R216–R224. PubMed PMID: 28977446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock MV, Hooker CM, Ota-Machida E, et al. DNA methylation markers and early recurrence in stage I lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008. March 13;358(11):1118–1128. PubMed PMID: 18337602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteller M. Relevance of DNA methylation in the management of cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2003. June;4(6):351–358. PubMed PMID: 12788407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartosch C, Lopes JM, Jeronimo C. Epigenetics in endometrial carcinogenesis - part 1: DNA methylation. Epigenomics. 2017. May;9(5):737–755. PubMed PMID: 28470096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warden CD, Lee H, Tompkins JD, et al. COHCAP: an integrative genomic pipeline for single-nucleotide resolution DNA methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013. June;41(11):e117 PubMed PMID: 23598999; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3675470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warden C. COHCAP analysis of CpG Island methylation for illumina 450k methylation arrays. Protocol Exchange. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meinshausen N, Meier L, Buhlmann P. p-Values for high-dimensional regression. J Am Stat Assoc. 2009. December;104(488):1671–1681. PubMed PMID: WOS:000273995500033; English. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasserman L, Roeder K. High-Dimensional variable selection. Ann Stat. 2009. October;37(5A):2178–2201. PubMed PMID: WOS:000268604900004; English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon R, Altman DG. Statistical aspects of prognostic factor studies in oncology. Br J Cancer. 1994. June;69(6):979–985. PubMed PMID: 8198989; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1969431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Quigley J, Xu R, Stare J. Explained randomness in proportional hazards models. Stat Med. 2005. February 15;24(3):479–489. PubMed PMID: 15532086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrell FE Jr., Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996. February 28;15(4):361–387. PubMed PMID: 8668867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Mara TA, Zhao M, Spurdle AB. Meta-analysis of gene expression studies in endometrial cancer identifies gene expression profiles associated with aggressive disease and patient outcome. Sci Rep. 2016. November 10;6:36677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, et al. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics. 2012. May;16(5):284–287. PubMed PMID: 22455463; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3339379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics. 2000. June;56(2):337–344. PubMed PMID: 10877287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatarano S, Chiyomaru T, Kawakami K, et al. Novel oncogenic function of mesoderm development candidate 1 and its regulation by MiR-574-3p in bladder cancer cell lines. Int J Oncol. 2012. April;40(4):951–959. PubMed PMID: 22179486; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3584521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu YY, Ji J, Lu Y, et al. High-resolution analysis of chromosome 5 and identification of candidate genes in gastric cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2006. February;28(2):84–87. PubMed PMID: 16750006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu K, Cai XY, Li Q, et al. OTX1 promotes colorectal cancer progression through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014. January 31;444(1):1–5. PubMed PMID: 24388989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imanieh MH, Bagheri F, Alizadeh AM, et al. Oxytocin has therapeutic effects on cancer, a hypothesis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014. October 15;741:112–123. PubMed PMID: 25094035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dery MC, Chaudhry P, Leblanc V, et al. Oxytocin increases invasive properties of endometrial cancer cells through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT-dependent up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-1, −2, and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein. Biol Reprod. 2011. December;85(6):1133–1142. PubMed PMID: 21816851; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4480429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avruch J, Khokhlatchev A, Kyriakis JM, et al. Ras activation of the Raf kinase: tyrosine kinase recruitment of the MAP kinase cascade. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56:127–155. PubMed PMID: 11237210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers GT, et al. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001. April;22(2):153–183. PubMed PMID: 11294822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010. October 19;19(4):491–505. PubMed PMID: 20951342; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3124840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mo JS, Park HW, Guan KL. The Hippo signaling pathway in stem cell biology and cancer. EMBO Reports. 2014. June;15(6):642–656. PubMed PMID: 24825474; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4197875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vleminckx K. Cell adhesion molecules In: Schwab M, editor. Encyclopedia of cancer. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2017. p. 885–891. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeramian A, Moreno-Bueno G, Dolcet X, et al. Endometrial carcinoma: molecular alterations involved in tumor development and progression. Oncogene. 2013. January 24;32(4):403–413. PubMed PMID: 22430211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang JY, Werner HM, Li J, et al. Integrative protein-based prognostic model for early-stage endometrioid endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016. January 15;22(2):513–523. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0104. PubMed PMID: 26224872; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4715969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coenegrachts L, Garcia-Dios DA, Depreeuw J, et al. Mutation profile and clinical outcome of mixed endometrioid-serous endometrial carcinomas are different from that of pure endometrioid or serous carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2015. April;466(4):415–422. PubMed PMID: 25677978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun Y, Zou X, He J, et al. Identification of long non-coding RNAs biomarkers associated with progression of endometrial carcinoma and patient outcomes. Oncotarget. 2017. August 08;8(32):52604–52613. PubMed PMID: 28881755; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5581054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Catasus L, D’Angelo E, Pons C, et al. Expression profiling of 22 genes involved in the PI3K-AKT pathway identifies two subgroups of high-grade endometrial carcinomas with different molecular alterations. Mod Pathol. 2010. May;23(5):694–702. PubMed PMID: 20173732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeimet AG, Reimer D, Huszar M, et al. L1CAM in early-stage type I endometrial cancer: results of a large multicenter evaluation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013. August 07;105(15):1142–1150. PubMed PMID: 23781004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Li J, Wen S, et al. CHRM3 is a novel prognostic factor of poor prognosis in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7(5):902–911. PubMed PMID: 26175851; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4494141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kratz JR, He J, Van Den Eeden SK, et al. A practical molecular assay to predict survival in resected non-squamous, non-small-cell lung cancer: development and international validation studies. Lancet. 2012. March 3;379(9818):823–832. PubMed PMID: 22285053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3294002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.