Abstract

Many nutritionists adopt feeding strategies designed to increase ruminal starch fermentation because ruminal capacity for starch degradation often exceeds amounts of starch able to be digested in the small intestine of cattle. However, increases in fermentable energy supply are positively correlated with increased instances of metabolic disorders and reductions in DMI, and energy derived by cattle subsequent to fermentation is less than that derived when glucose is intestinally absorbed. Small intestinal starch digestion (SISD) appears to be limited by α-glycohydrolase secretions and a precise understanding of digestion of carbohydrates in the small intestine remains equivocal. Interestingly, small intestinal α-glycohydrolase secretions are responsive to luminal appearance of milk-specific protein (i.e., casein) in the small intestine of cattle, and SISD is increased by greater postruminal flows of individual AA (i.e., Glu). Greater flows of casein and Glu appear to augment SISD, but by apparently different mechanisms. Greater small intestinal absorption of glucose has been associated with increased omental fat accretion even though SISD can increase NE from starch by more than 42% compared to ruminal starch degradation. Nonetheless, in vitro data suggest that greater glucogenicity of diets can allow for greater intramuscular fat accretion, and if greater small intestinal absorption of glucose does not mitigate hepatic gluconeogenesis then increases in SISD may provide opportunity to increase synthesis of intramuscular fat. If duodenal metabolizable AA flow can be altered to allow for improved SISD in cattle, then diet modification may allow for large improvements in feed efficiency and beef quality. Few data are available on direct effects of increases in SISD in response to greater casein or metabolizable Glu flow. An improved understanding of effects of increased SISD in response to greater postruminal flow of Glu and casein on improvements in NE and fates of luminally assimilated glucose could allow for increased efficiency of energy use from corn and improvements in conversion of corn grain to beef. New knowledge related to effects of greater postruminal flow of Glu and casein on starch utilization by cattle will allow nutritionists to more correctly match dietary nutrients to cattle requirements, thereby allowing large improvements in nutrient utilization and efficiency of gain among cattle fed starch-based diets.

Keywords: amino acid, cattle, small intestine, starch digestion

INTRODUCTION

Limitations to efficient production of animal products (i.e., meat and milk) by cattle are often associated with dietary restrictions in NE to support physiologically productive purposes. Small intestinal starch digestion (SISD) can provide greater amounts of NE in comparison to ruminal fermentation (Owens et al., 1986; Huntington, 1997; Harmon, 2009; Owens et al., 2016), but extent of small intestinal digestion is limited in comparison to amounts of starch able to be fermented in the rumen. Several authors have concluded that several factors (e.g., physiochemical characteristics of starch, intestinal retention time, hydrolytic capacity) can limit SISD in cattle. Several attempts to model (Huntington, 1997; Mills et al., 2017) SISD have concluded that utilization of dietary energy from starch is potentially limited by α-glycohydrolase secretions in cattle. Nonetheless, imprecision in recent attempts to model SISD (Mills et al., 2017) and inherently large estimates of variance in measures of SISD among cattle fed grain-based diets (Owens et al., 1986) indicate that a precise understanding of digestion of carbohydrates in the small intestine of cattle remains equivocal. Thus, most ruminant nutritionists currently adopt feeding strategies designed to increase ruminal starch fermentation to improve productive efficiencies. However, increases in fermentable energy supply are positively correlated with increased instances of metabolic disorders and reductions in DMI, and energy derived by cattle subsequent to fermentation is less than that derived when glucose is absorbed intestinally. Yet, pancreatic α-amylase secretions are responsive to greater luminal appearance of high-quality protein in the small intestine of cattle, and SISD is increased by greater postruminal flows of individual AA (i.e., L-Glu). Indeed, several authors have speculated that transient asynchronies in AA and carbohydrate flow to different segments of the alimentary tract likely contribute to limits in SISD. A greater understanding of effects of AA flows to the small intestine on SISD will allow diets to more appropriately match needs of cattle and facilitate increased efficiencies of energy utilization from dietary starch while reducing incidences of metabolic disorders.

SMALL INTESTINAL STARCH DIGESTION IN RUMINANTS

The action of starch digestion occurs similarly in both ruminants and nonruminants, and its digestion can be separated into three independent segments (Huntington, 1997): 1) hydrolysis by α-amylase to smaller oligosaccharides, 2) release of glucose from oligosaccharides by α-glycohydrolases closely associated with intestinal epithelium, and 3) transport of glucose from the lumen by transmembrane glucose transporters in intestinal epithelia. Digestion of starch appearing in the lumen of the small intestine is initiated by α-amylase that is secreted from acinar cells in the pancreas as part of its exocrine function (Brannon, 1990). α-Amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) is secreted in the lumen in its active form where it attacks 5, α-1,4-linked, resident glucose molecules in starch and releases smaller oligosaccharides (i.e., maltose, maltotriose and branched limit-dextrins). Released oligosaccharides are subsequently hydrolyzed to glucose by brush border α-glycohydrolases (i.e., isomaltase, maltase, glucoamylase) that are secreted by, and are closely associated with enterocytes. Ultimately, glucose molecules released from starch are actively transported across the brush border membrane.

Typically, ruminants digest only 5% to 20% of dietary starch consumed postruminally (Harmon, 1992), despite digestion of starch being theoretically more energetically efficient in the small intestine. When Owens et al. (1986) reviewed the available literature, they reported that small intestinal starch provides 42% more energy than starch fermented in the rumen. Similarly, McLeod et al. (2001) reported that the partial efficiency of converting ME from partially hydrolyzed starch to tissue energy was increased 25% when partially hydrolyzed starch was infused abomasally vs. ruminally. Additionally, when the observed partially efficiency for conversion of ME from partially hydrolyzed starch to tissue energy is corrected for the expected small intestinal digestibility of partially hydrolyzed starch (i.e., 88%; Branco et al., 1999), the increases reported by McLeod et al. (2001) are in agreement (i.e., a 42% increase) with the report of Owens et al. (1986). Apparent increases in energy available from SISD compared to starch ruminally fermented led Owens et al. (2016) to calculate that shifting site of starch digestion from steam-flaked corn from the rumen to the small intestine by 15% could improve the energetic efficiency of cattle by 3.3%. However, it is known that SISD in cattle is limited (Orskov, 1976; Owens et al., 1986; Theurer, 1986; Harmon, 1992; Huntington, 1997), and this limitation is proportionally related to small intestinal starch appearance rather than having an absolute maximal value beyond which no further starch can be digested (Orskov, 1976; Theurer, 1986). Orskov et al. (1969) were the first to suggest that limitations in SISD could be expressed as a proportion of starch flowing to the small intestine. These authors (Orskov et al., 1969) concluded that ileal starch concentration could be calculated as , where y is ileal starch concentration and x is abomasal concentration. This model suggests that SISD is linearly related to starch flow to the abomasum, but limited to only 56% digestibility. However, digestion of starch is typically greater in sheep than cattle when either of these species are fed similar diets (Orskov, 1976). Therefore, it may be that SISD is limited to an even greater extent in cattle than sheep. When Huntington (1997) summarized data from recent reviews on limitation of SISD in cattle and applied a linear regression model to the data, he reported that the slope indicated a digestibility of 55%. A proportional limitation in SISD in ruminants suggests that digestion is responsive to nutrient intake, flow to the abomasum, and energy intake. However, as is commonly observed in nature, it has been demonstrated that maximal limits of small intestinal digestive enzymes in ruminants can be exceeded and absolute limitations may exist (Orskov et al., 1970), but this is yet to be observed with starch flows that could be achieved naturally by the animal. Regardless, it is clear that SISD in ruminants is limited in comparison to nonruminants who are typically capable of digesting nearly all starch appearing luminally in the small intestine (Brannon, 1990).

POTENTIAL LIMITATIONS OF SMALL INTESTINAL STARCH DIGESTION IN RUMINANTS

A clear explanation of the discrepancy between small intestinal starch digestibilities in ruminants and nonruminants has received considerable attention by many researchers; however, these species differences remain a biological enigma and further study is necessary before greater achievements in starch digestion of ruminants can be obtained. Owens et al. (1986) described some potential physiological factors that may explain the reduced ability of ruminants to digest starch in the small intestine: 1) inadequate time for sufficient digestion, 2) reduced capabilities in glucose absorption from the lumen, and 3) deficient activities of small intestinal α-glycohydrolases (i.e., α-amylase and brush border α-glycohydrolases).

Digesta can flow through the ruminant small intestine in less than 3 h (Owens et al., 1986). Under normal feeding situations, flow of digesta to the small intestine is constant (Merchen, 1988), but alterations in DMI can affect the rate of digesta passage (Merchen, 1988). Additionally, flow of digesta through the small intestine is closely regulated and responsive to nutrient composition. Greater appearance of nutrients capable of enzymatic degradation at distal locations in the gastrointestinal tract leads to increased secretion of hormonal and neural regulators that act to slow digesta passage and increase digestion of nutrients in more proximal locations (Croom et al., 1992). If digestion is limited by rates of digesta passage in the small intestine of ruminants, the response of these regulators must be minimal or their secretion must be too insignificant to elicit a response. Even if rates of digesta passage limit digestion, this factor is not independent of either activity or amounts of small intestinal α-glycohydrolases, and limitations in SISD associated with rates of passage would certainly be mitigated with increasing amounts and activities of α-glycohydrolases.

Monosaccharides (e.g., glucose, fructose, galactose) can be absorbed from the small intestinal lumen through both energy-dependent (facilitated by the energy-dependent production of a Na+ gradient) or energy-independent routes (Van Beers et al., 1995). The Na+-glucose transporter 1 (SGLT1) is specific to glucose and galactose; this transporter utilizes the energy-dependent Na+ gradient. Energy-independent assimilation of monosaccharides is mediated either by the broad transport of glucose, galactose, and fructose by glucose transporter 2, glucose transporter 5, or via paracellular absorption. Greater flows of polymerized starch to the small intestine apparently increase expression of both SGLT1 and glucose transporter 2, but not glucose transporter 5 (Liao et al., 2010). Energy-independent absorption, however, requires relatively large concentrations of luminal monosaccharides or increased fluid flow capable of penetrating tight-junctions of enterocytes (Pappenheimer, 1993; Wright et al., 1994), and Krehbiel et al. (1996) reported that nearly all glucose absorbed from the intestinal lumen of cattle was likely assimilated via energy-dependent or energy-independent transporters. Thus, transit of glucose from the lumen of the small intestine to the cytosol of the enterocyte is thought to be dominated by the activity of SGLT1 (Wright, 1993; Shirazi-Beechey et al., 2011).

Expression of SGLT1 has been reported in sheep (Shirazi-Beechey et al., 1991) and cattle (Rodriguez et al., 2004; Guimaraes et al., 2007). Reports (Mayes and Orskov, 1974; Kreikemeier and Harmon, 1995) of free glucose concentrations in the terminal ileum of ruminants beyond the apparent affinity for glucose of SGLT1 have led to speculations that starch digestion may be first limited by transport from the lumen. However, Shirazi-Beechey et al. (1991) observed that SGLT1 is upregulated between 50- and 80-fold in response to increases in luminal free glucose. Several researchers (Bauer et al., 2001; Guimaraes et al., 2007) have studied the relationship of glucose uptake ability and capabilities for hydrolysis of oligosaccharides along the small intestine of cattle. These authors reported that glucose uptake abilities exceed capabilities of hydrolytic cleavage of oligosaccharides along all locations of the small intestine except the ileum. Bauer et al. (2001) speculated that reports of free glucose at the terminal ileum were likely a result of lesser concentrations of SGLT1 in that region relative to α-glycohydrolases. Excretion of pancreatic α-amylase occurs via the pancreatic duct located at the terminal duodenum (St-Jean et al., 1992), and it is likely that hydrolytic cleavage of starch occurs at its greatest rates near that location (Bauer et al., 2001). Apparently, the digestive physiology of ruminants seems well suited to maximize absorption of free glucose liberated from the hydrolytic activity of α-amylase and the brush border α-glycohydrolases because the greatest concentrations of SGLT1 are located in the jejunum (Bauer et al., 2001; Guimaraes et al., 2007), and it would seem unlikely that transport of free glucose is first limiting to starch assimilation in the small intestine of ruminants. Indeed, when Huntington and Reynolds (1986) infused either glucose or starch postruminally, approximately 65% of glucose was recovered in the portal blood supply whereas only 35% of infused starch appeared. Additionally, when hydrolyzed starch is postruminally infused in cattle, glucose uptake by SGLT1 remains unaffected (Bauer et al., 2001; Guimaraes et al., 2007). If the ability for SGLT1 regulation by free glucose is conserved between ruminants, this would suggest that other factors, such as hydrolytic cleavage of polysaccharides and oligosaccharides, is more limiting to SISD.

POTENTIAL LIMITATIONS OF SMALL INTESTINAL CARBOHYDRASES IN RUMINANTS

It is likely that the primary factor currently limiting small intestinal digestion of starch is suboptimal capabilities for hydrolytic cleavage of polysaccharides and oligosaccharides. Early investigations concerning limitations of small intestinal α-glycohydrolases using sheep led some (Mayes and Orskov, 1974) to conclude that α-amylase was not limiting to SISD. However, sheep are more efficient digesters of starch than cattle (Orskov, 1976) with greater postruminal digestibilities of starch (Tucker et al., 1968), and it is known that small intestinal digestion is significantly greater in sheep than cattle (Theurer, 1986). Thus, responses in sheep may not translate to equivalent responses in cattle. Kreikemeier and Harmon (1995) measured small intestinal disappearance and portal flux of glucose when they abomasally infused glucose, corn dextrins, or cornstarch. These authors (Kreikemeier and Harmon, 1995) reported that both starch and ethanol-insoluble reducing sugars (i.e., oligosaccharides) were present in digesta of the terminal ileum when cattle were infused with either cornstarch or corn dextrins. Even though observed means for portal glucose flux were unable to be separated, due to a relatively large coefficient of variation (28%), those cattle infused with corn dextrins had 163% more glucose appearing in the portal blood supply than those infused with corn starch. Based on their results, Kreikemeier and Harmon (1995) speculated that either α-amylase or brush border α-glycohydrolases may be first limiting to SISD in cattle. Others (Kreikemeier et al., 1990) have reported that both pancreatic α-amylase and a small intestinal brush border α-glycohydrolase (i.e., glucoamylase) in calves are affected by energy intake and cereal grain content of the diet. Kreikemeier et al. (1990) fed calves either a forage- or grain-based diet and restricted intakes to either at or twice the level required for maintenance. They observed that both α-amylase and glucoamylase activities were increased (240% and 156%, respectively) when energy intake was doubled. However, when starch content was increased, activities of both carbohydrases were paradoxically decreased. Interestingly, as energy content was increased in diets with grain, the disparity between grain and forage-fed cattle in activity for glucoamylase was reduced (27% to 15%), but for activity of α-amylase it was increased (40% to 46%). Similarly, several others have reported reductions in α-amylase activity (Swanson et al., 2002) or starch digestion (Taniguchi et al., 1995; Branco et al., 1999) when concentrations of starch flowing to the small intestine increase. Guimaraes et al. (2007) reported values for brush border maltase activity that were increased approximately 179% when starch was infused. Furthermore, these authors (Guimaraes et al., 2007) observed an equivalent increase in maltase activity when casein was infused. Additionally, Le Huerou et al. (1992) reported that activities of small intestinal brush border α-glycohydrolases continually increased with age in weaned calves. Collectively, these data may suggest that as finishing cattle are fed to amounts more similar to typical intakes that α-amylase may become more limiting to SISD than brush border α-glycohydrolases. Indeed, when Huntington (1997) developed models to simulate SISD in cattle, he concluded that rate and extent of starch assimilation were most limited by the hydrolytic capabilities of pancreatic α-amylase rather than brush border α-glycohydrolase activities or glucose transport. Nonetheless, Mills et al. (2017) developed a model to describe SISD in lactating cows and calculated that brush border α-glycohydrolases or passage of oligosaccharides from the unstirred water layer limited SISD. Thus, limitations in SISD in cattle are likely a combination of both pancreatic α-amylase and the brush border α-glycohydrolases.

ADAPTATION OF α-GLYCOHYDROLASE SECRETIONS TO DIETARY PROTEIN AND AMINO ACIDS

Researchers have suggested for over a century that enzymatic secretions of the pancreas in nonruminants are responsive to dietary components flowing to the small intestine (Pavlov, 1898; Snook, 1971; Merritt and Karn, 1977; Brannon, 1990). A dependence between carbohydrate and functional AA (i.e., those AA that regulate key metabolic pathways to improve development, growth, health, lactation, and reproduction; Wu, 2010) concentration flowing to the duodenum has been characterized in nonruminants for optimal pancreatic α-amylase secretions (Snook, 1971; Johnson et al., 1977; Riepl et al., 1996). Snook (1971) reported that pancreatic α-amylase secretions were increased 114% when up to 30% of the diet was replaced with casein in rats. Johnson et al. (1977) provided diets with either zein or casein; they observed increased responses in pancreatic enzymatic secretions of rats when casein was fed. Additionally, they (Johnson et al., 1977) noted that when zein was reconstituted with AA, to resemble casein, responses in pancreatic enzyme secretions were similar to when casein was provided. Thus, these authors (Johnson et al., 1977) concluded that high-quality protein flow to the small intestine was essential for optimal secretions of pancreatic enzymes. Schick et al. (1984) replaced dietary carbohydrate with casein fed to rats and observed that response in α-amylase secretion was quadratic and greatest when casein composed 22% of the diet. Therefore, they (Schick et al., 1984) concluded that a proportional relationship was required between small intestinal carbohydrate and functional AA flow for optimal starch digestion and speculated that this response was likely conserved across many species. Indeed, similar responses have been reported in man (Riepl et al., 1996). Yet, some (Croom et al., 1992) have speculated that pancreatic enzymatic secretions of ruminants are dissimilar and not responsive to composition of nutrients flowing to the small intestine because postprandial passage rates are more constant.

Nonetheless, we now know that pancreatic secretions of enzymes in ruminants are responsive to changes in composition of digesta flowing to the lumen of the small intestine (Harmon, 1992; Huntington, 1997; Swanson et al., 2004). A preponderance of the published data suggests that response in pancreatic α-amylase secretion to casein (i.e., AA) is conserved between ruminants and nonruminants. Wang and Taniguchi (1998) reported that increased postruminal starch depressed α-amylase secretion, but additions of postruminal casein restored α-amylase secretions to that of the control. Direct measures of rate and content of pancreatic secretions among surgically modified steers in response to increasing abomasal infusions of casein were reported by Richards et al. (2003). These researchers (Richards et al., 2003) observed linear increases in concentration, specific activity, and rate of pancreatic α-amylase with greater amounts of casein. Swanson et al. (2008) fed increasing levels of ruminal-escape soybean meal and reported similar responses in pancreatic enzymes to Richards et al. (2003) that correlated with greater live animal performance characteristics, and speculated that greater amounts of postruminal protein (i.e., AA) led to greater rates and amounts of enzymatic secretions. Recent reports (Swanson et al., 2004; Liao et al., 2009) suggest that interactions between supplemental proteins (i.e., AA) and α-amylase might be dynamic and that requirements for functional AA to optimize pancreatic secretions may be proportional to starch appearing in the lumen of the small intestine. Ostensibly, postruminal protein and likely AA increase pancreatic α-amylase secretions in cattle. However, a significant paucity in the available data exists for direct effects of functional AA on pancreatic α-amylase secretions, and data are necessary in this area before starch digestion can be optimized in most finishing cattle feeding systems.

Based on observations of digesta flow from the abomasum (Merchen, 1988) and measurements of pancreatic secretions in relation to the duodenal migrating myoelectric complex in cattle (Zabielski et al., 1997), it appears that ruminants are in a continuous state of digestion that is analogous to the intestinal contributing phase in nonruminants. Regulation of pancreatic secretions during the intestinal contributing phase has been attributed almost entirely to cholecystokinin (CCK) secretion by the gut (Konturek et al., 2003), and although this accounts for a preponderance of pancreatic response in nonruminants (~70%), it may be suggested that CCK mediates the entire pancreatic response in ruminants.

Cholecystokinin is produced by enteroendocrine I cells in small intestinal mucosa (Wang et al., 2002; Zabielski, 2003; Jaworek et al., 2010; Nilaweera et al., 2010). The apical membrane of enteroendocrine I cells contacts the small intestinal lumen, and sensing of luminal nutrients via apically located protein receptors and transporters facilitates increased secretion of CCK. Considerable effort has focused on elucidating the precise method by which enteroendocrine I cells sense luminal nutrients, and which nutrients act as CCK secretagogues.

Increased dietary protein has been associated with increased plasma CCK in both nonruminants (Konturek et al., 1973; Nishi et al., 2003; Veldhorst et al., 2008) and ruminants (Furuse et al., 1992). Intestinal release of CCK is also apparently regulated by two CCK releasing peptides, monitor peptide and luminal CCK releasing factor, which are produced by the pancreas and enterocytes, respectively (Miyasaka and Funakoshi, 1992).

Typically, in nonruminants, it is generally considered that basal secretions of monitor peptide and luminal CCK releasing factor do not influence release of CCK from the alimentary tract (Sale et al., 1977; Konturek et al., 2003) because sufficient trypsin is available for digestion of luminal CCK releasing factor and adsorption to monitor peptide (Konturek et al., 2003). Presently, we are unaware of any data that directly measured the effects of monitor peptide and luminal CCK releasing factor in ruminants. Direct extrapolation of conclusions from nonruminant data might lead one to conclude that these peptides do not exert influence on release of CCK from the ruminant small intestine because ruminants apparently do not experience postprandial increases in pancreatic secretions (Kato et al., 1984; Zabielski et al., 1997). An alternative hypothesis may be that monitor peptide and luminal CCK releasing factor may potentiate significant responses in CCK release from the small intestine in ruminants; particularly, in response to greater amounts of protein flowing to the duodenum. Indeed, flow of digesta to the small intestine in ruminants is apparently continuous (Merchen, 1988; Zabielski et al., 1997) and typically contains considerable amounts of protein (Titgemeyer, 1997). Also, the pH of digesta in the proximal duodenum of cattle is low (pH ~ 3; Russell et al., 1981; Hibberd et al., 1985; Hill et al., 1991), and monitor peptide binds trypsin in a 1:1 ratio at pH 3 to 7 (Konturek et al., 2003). Thus, a continuous flow of protein and a low pH of duodenal digesta in cattle may limit digestion of luminal CCK releasing factor by trypsin in the regions of the small intestine most densely populated with enteroendocrine I cells (Moran and Kinzig, 2004; Cummings and Overduin, 2007); however, small intestinal digestion of protein in cattle is generally considered to be extensive (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2016), and at least one report in cattle failed to measure increases in plasma CCK in response to greater luminal protein supplies (Swanson et al., 2004). Nonetheless, several G-protein transmembrane receptors have been identified in immortalized cells analogous to enteroendocrine I cells that are responsive to protein hydrolysates and L-AA. Also, the peptide transporter PEPT1 has been suggested to effect CCK secretion by enteroendocrine I cells (Choi et al., 2007). Thus, greater postruminal flows of protein or specific AA (e.g., glutamic acid) may increase SISD in cattle by augmenting pancreatic secretions via greater CCK release. However, it is possible that the precise mechanism in which CCK secretion is increased differs in response to greater postruminal flow of protein or a specific AA.

Currently, we are not aware of any direct measures of greater postruminal protein or AA flows on brush border α-glycohydrolases in cattle. However, our recent data (Brake et al., 2014a) indicate that greater postruminal flows of Glu increase SISD and luminal hydrolysis of small-chain oligosaccharides in cattle. Thus, it is possible that greater postruminal flows of Glu increase SISD by augmenting brush border α-glycohydrolases in cattle.

Regulation of brush border α-glycohydrolases is apparently far less complex than regulation of pancreatic α-amylase secretion. Sucrase-isomaltase is expressed to a much greater extent than maltase-glucoamylase in nonruminants and is thought to be the primary enzyme that hydrolyzes small-chain oligosaccharides in these species (Van Beers et al., 1995). Ruminants, however, have no measurable sucrase activity in the small intestine (Siddons, 1968) and this is strong evidence that the evolutionary divergence of ruminants has led to some level of altered small-chain oligosaccharide digestion (Harmon, 1992). In fact, ruminants commonly express greater activity of maltase-glucoamylase throughout the small intestine (Russell et al., 1981; Janes et al., 1985; Kreikemeier et al., 1990), and it may be that small-chain oligosaccharide digestion is primarily controlled by this enzyme in ruminant small intestines.

Basal amounts of expression of all the brush border α-glycohydrolases is developmentally imprinted, early on in fetal development, and is relatively insensitive to effects of hormones (Van Beers et al., 1995). Despite the fact that brush border α-glycohydrolase expression is developmentally imprinted there is strong evidence that general regulatory mechanisms can influence brush border α-glycohydrolase expression in nonruminants (Van Beers et al., 1995). Goda et al. (1983) reported that decreased starch intake by rats led to rapid decreases in maltase-glucoamylase and other brush border α-glycohydrolase activities. Bustamante et al. (1986) and Morrill et al. (1989) observed significant increases in brush border α-glycohydrolase activities that corresponded to increased starch intake in rats. Interestingly, starvation increased expression of jejunal sucrase-isomaltase, but not lactase in rats (Nsi-Emvo et al., 1994). Furthermore, when rats were re-fed, a band of enterocytes migrating up the intestinal villi with upregulated sucrase-isomaltase existed (Nsi-Emvo et al., 1994). These data have been interpreted to suggest that enterocyte regulation of brush border α-glycohydrolases is only capable of occurring in developing stem cells located in the intestinal crypt and that mature enterocytes are incapable of differentially expressing α-glycohydrolases. It is yet to be clearly defined whether these apparent mechanisms for regulation of brush border α-glycohydrolase expression in nonruminant enterocytes are controlled at the transcriptional level.

To date, there are no reports that indicate that cattle are capable of increasing small intestinal brush border α-glycohydrolase activity in response to greater luminal flows of small-chain oligosaccharides; however, several authors (Russell et al., 1981; Khatim and Osman, 1983; Kreikemeier et al., 1990; Bauer et al., 2001) have reported the relative activities of small intestinal brush border α-glycohydrolases along the small intestine. All of these reports (Russell et al., 1981; Khatim and Osman, 1983; Kreikemeier et al., 1990; Bauer et al., 2001) indicated that brush border α-glycohydrolase activity was greatest in the jejunum and significantly less in the proximal and distal portions of the small intestine. Russell et al. (1981) fed cattle increasing amounts of energy as either a forage- or corn-based diet and observed no effects on intestinal maltase activity. Yet, Janes et al. (1985) observed an increased hydrolytic capacity of sheep fed a corn- vs. a grass-based diet. Maltase activity was not affected by treatment, but increases in isomaltase activity mirrored increases in hydrolytic capacity. Additionally, the report of Janes et al. (1985) may indicate an increase in the functional area in the small intestine in which small-chain oligosaccharides may be hydrolyzed because isomaltase activity was greatest in the proximal one-third of the small intestine for corn-fed sheep rather than in the middle third. Kreikemeier et al. (1990) fed cattle a forage- or corn-based diet at one or two times maintenance energy requirements and reported that brush border α-glycohydrolase activities were unaffected; however, maltase and isomaltase activities were greater over the entire small intestine as a result of a longer small intestine when more energy was fed. When Harmon (1992) reviewed these data, he concluded that small intestinal brush border α-glycohydrolase activity of cattle was responsive to dietary energy rather than substrate and that responses of cattle were less than their nonruminant counterparts.

A precise understanding of responses among small intestinal α-glycohydrolases to greater postruminal protein flows is yet to be elucidated; however, an increasing number of reports indicate that SISD in cattle is augmented by greater postruminal protein flows. Taniguchi et al. (1995) studied nutrient fluxes across splanchnic tissues with either ruminal or postruminal supply of casein when cornstarch was provided abomasally. These authors (Taniguchi et al., 1995) observed that as postruminal protein supply increased, a concomitant increase occurred for glucose release across both the portal-drained viscera and total splanchnic tissues leading to increased circulating glucose concentrations. These improvements in circulating glucose were related to a nearly 50% improvement in N retention by these cattle.

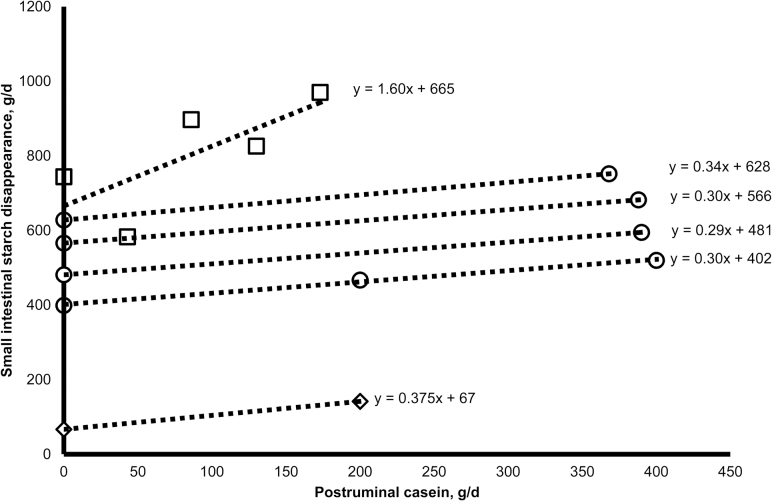

Apparently, greater postruminal flows of casein linearly increase SISD in cattle (Figure 1). Richards et al. (2002) directly measured small intestinal cornstarch digestibility with titrated levels of casein provided abomasally and observed a 1.60 g increase in SISD for each gram of casein abomasally infused. Others (Taniguchi et al., 1995) measured a more modest increase (0.38 g increase in glucose released to the portal-drained viscera for each gram of casein abomasally infused) in glucose release to the portal-drained viscera among cattle provided abomasal infusions of starch in response to abomasal casein infusion. We have conducted a series of studies (Brake et al., 2014a, 2014b; Blom et al., 2016) and measured an average increase of 0.31 ± 0.02 in SISD for each gram of casein duodenally infused. Furthermore, Brake et al. (2014b) reported that linear increases among SISD in cattle to greater amounts of postruminal casein were rapid and that greater postruminal flows of AA can increase SISD in cattle similar to casein.

Figure 1.

Effects of postruminal casein flow on small intestinal starch digestion in cattle (Taniguchi et al., 1995, ◊; Richards et al., 2002, □; Brake et al., 2014a, 2014b, ○; Blom et al., 2016, ○).

EFFECT OF GLUTAMIC ACID ON SMALL INTESTINAL STARCH DIGESTION IN CATTLE

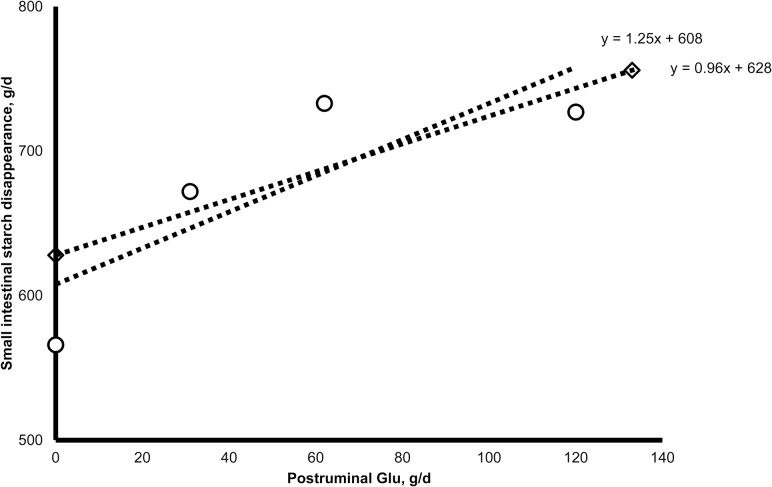

Clearly, greater postruminal flows of casein increase SISD in cattle (Taniguchi et al., 1995; Richards et al., 2002; Brake et al., 2014a, 2014b; Blom et al., 2016). When Harmon (2009) reviewed the available data, he concluded that a major nutritional factor affecting small intestinal hydrolytic capacity in cattle was energy provided from postruminal protein flows. Glutamic acid is the primary anaplerotic substrate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle in small intestinal epithelium in cattle (El-Kadi et al., 2009). Few data are available on effects of greater flows of Glu to the small intestine. Our data (Brake et al., 2014b) indicate that mixtures of AA similar to casein, mixtures of nonessential AA similar to that provided by casein or Glu alone can increase SISD. Additionally, casein and a mixture of essential AA similar to that provided by casein appeared to increase pancreatic α-amylase secretion (indicated by greater ileal flows of small-chain α-glycosides), but a mixture of essential AA similar to that provided by casein did not increase SISD (Brake et al., 2014b). In contrast, a mixture of nonessential AA similar to that provided by casein and Glu increased SISD, but not ileal flows of oligosaccharides (i.e., ethanol-soluble starch) suggesting that greater postruminal flow of casein and Glu increases SISD but by apparently different mechanisms. Furthermore, our data suggest that increases in SISD in response to increases in duodenal Glu are greater in comparison to increases in SISD in response to greater postruminal casein flow (Figure 2). Brake et al. (2014b) observed a 0.96 g/d increase in SISD for each gram of duodenal Glu, and Blom et al. (2016) reported that postruminal Glu increased SISD by 1.25 g/d for each gram of duodenal Glu flow.

Figure 2.

Effects of postruminal Glu flow on small intestinal starch digestion in cattle (Brake et al., 2014a, 2014b, ◊; Blom et al., 2016, ○).

More data are needed before a complete understanding of the physiological responses to greater postruminal flows of Glu can be elucidated. Additionally, increased knowledge related to tissue utilization of carbon from enhanced small intestinal assimilation of starch in cattle is necessary to understand the benefit of greater postruminal Glu flows to cattle production.

EFFECTS OF GREATER POSTRUMINAL STARCH DIGESTION ON TISSUE ACCRETION

Glucose from greater SISD in cattle must either be oxidized or used for tissue gain (McLeod et al., 2006). Data related to effects of greater SISD on body composition and tissue accretion are limited. McLeod et al. (2001) ruminally or abomasally infused a partially hydrolyzed starch in cattle limit-fed a forage diet. These authors (McLeod et al., 2001) reported that abomasal infusions of partially hydrolyzed starch increased retained energy to a greater extent than ruminal infusions. Additionally, 70% of the retained energy from ruminal infusion of partially hydrolyzed starch was partitioned to lipid and the remainder was protein (McLeod et al., 2001). Similarly, Blom et al. (2016) measured linear increases in SISD in response to greater duodenal flow of Glu, but reported that despite large increases in SISD (and presumably retained energy) that N retention did not differ. Thus, increases in retained energy from abomasal infusions of partially hydrolyzed (McLeod et al., 2001) or raw corn starch (Blom et al., 2016) appeared to be primarily associated with lipid accretion. McLeod et al. (2007) suggested that differences in tissue accretion related to site of starch digestion in cattle is apparently independent of energy and is likely impacted to a greater extent by differences in nutrients absorbed from the alimentary tract.

Generally, contribution of glucose carbon to lipid accretion in cattle is largely deposited in intramuscular fat, and contributions of glucose carbon to other fat depots are small compared to contributions from acetic acid (Smith and Crouse, 1984). However, Nayananjalie et al. (2015) reported that incorporation of acetic acid and glucose carbons to palmitate synthesis among different fat depots did not differ in vivo. Nonetheless, McLeod et al. (2007) reported that abomasal infusions of partially hydrolyzed starch increased intramuscular fat in the Longissimus dorsi; however, fat associated with the alimentary tract, pancreas, and kidney of cattle was also increased. These authors (McLeod et al., 2007) calculated that 35% of increases in lipid accretion were associated with alimentary tissues. Nonetheless, shifting site of starch digestion to the small intestine can increase the glucogenicity of the diet, and greater contributions of glucose to intramuscular fat could increase carcass quality despite greater lipid accretion associated with alimentary tissues.

Understanding the fate of glucose carbon is needed to determine the value of added gain in cattle when site of starch digestion is shifted from the rumen to the small intestine. Shifting site of starch digestion provides large opportunity to increase rates of gain in cattle (Owens et al., 1986; McLeod et al., 2001); however, gain as lipid associated with alimentary tissues provides little value to cattle production. Clearly, increase in gain from shifting site of starch digestion from the rumen to small intestine has value to cattle because intramuscular fat in the Longissimus dorsi is increased, but lipid accretion among alimentary tissues is also increased (McLeod et al., 2007). Currently, no data are available for effects of increasing SISD with greater postruminal flows of protein or Glu on lipid accretion in cattle. Perhaps increases in alimentary lipid from glucose or acetic acid carbon are mitigated by greater postruminal flows of protein or Glu, because Glu is the major anaplerotic substrate for the tricarboxylic acid cycle in small intestinal epithelium (El-Kadi et al., 2009). Additional data are needed before a precise understanding of the value of increasing SISD with greater postruminal flows of protein or Glu in cattle can be obtained.

CONCLUSIONS

Improving SISD in finishing cattle provides large potential for increases in efficiency of energy use from starch. If direct effects of postruminal Glu on SISD in cattle were elucidated, it is possible that energetic efficiency of cattle fed diets with large amounts of starch could be increased. Additionally, enhanced nutritional models may be developed to more accurately predict responses among cattle consuming proteins with greater amounts of metabolizable Glu. This would facilitate maximal amounts of starch digestion and energy available for growth in most finishing cattle feeding systems. Clearly, if this were achieved, nutritionists would be able to more correctly match dietary nutrients to those required, and this may facilitate improved nutrient utilization and efficiencies of gain in finishing cattle.

Footnotes

This material is based on the work that is supported by the Foundational Program (grant no. 2016-67016-24862) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. This material is a contribution from the South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station, Brookings, SD, 57007.

Based on a presentation at the Ruminant Nutrition Symposium entitled “Effects of postruminal flows of protein and amino acids on small intestinal starch digestion in beef cattle” held at the 2017 ASAS-CSAS Annual Meeting, July 9, 2017, Baltimore, MD.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bauer M. L., Harmon D. L., Bohnert D. W., Branco A. F., and Huntington G. B.. 2001. Influence of alpha-linked glucose on sodium-glucose cotransport activity along the small intestine in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 79:1917–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom E. J., Anderson D. E., and Brake D. W.. 2016. Increases in duodenal glutamic acid supply linearly increase small intestinal starch digestion but not nitrogen balance in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 94:5332–5340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brake D. W., Titgemeyer E. C., and Anderson D. E.. 2014a. Duodenal supply of glutamate and casein both improve intestinal starch digestion in cattle but by apparently different mechanisms. J. Anim. Sci. 92:4057–4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brake D. W., Titgemeyer E. C., Bailey E. A., and Anderson D. E.. 2014b. Small intestinal digestion of raw cornstarch in cattle consuming a soybean hull-based diet is improved by duodenal casein infusion. J. Anim. Sci. 92:4047–4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco A. F., Harmon D. L., Bohnert D. W., Larson B. T., and Bauer M. L.. 1999. Estimating true digestibility of nonstructural carbohydrates in the small intestine of steers. J. Anim. Sci. 77:1889–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon P. M. 1990. Adaptation of the exocrine pancreas to diet. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 10:85–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante S. A., Goda T., and Koldovsky O.. 1986. Dietary regulation of intestinal glucohydrolases in adult rats: comparison of the effect of solid and liquid diets containing glucose polymers, starch, or sucrose. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 43:891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S., Lee M., Shiu A. L., Yo S. J., Hallden G., and Aponte G. W.. 2007. GPR93 activation by protein hydrolysate induces CCK transcription and secretion in STC-1 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 291:G753–G761. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00516.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croom W. J., Bull L. S., and Taylor I. L.. 1992. Regulation of pancreatic exocrine secretion in ruminants: A review. J. Nutr. 122:191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings D. E., and Overduin J.. 2007. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J. Clin. Invest. 117:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kadi S. W., Baldwin R. L. VI, McLeod K. R., Sunny N. E., and Bequette B. J.. 2009. Glutamate is that major anaplerotic substrate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle of isolated rumen epithelial and duodenal mucosal cells from beef cattle. J. Nutr. 139:869–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M., Kato M., Yang S. I., Asakura K., and Okumura J.. 1992. Influence of dietary protein concentrations or of duodenal amino acid infusion on cholecystokinin release in goats. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Comp. Physiol. 101:635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda T., Yamada K., Bustamante S., and Koldovsky O.. 1983. Dietary-induced rapid decrease of microvillar carbohydrase activity in rat jejuno-ileum. Am. J. Physiol. 245:G418–G423. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.1983.245.3.G418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes K., Hazelton S., Matthews J., Swanson K., Harmon D., and Branco A.. 2007. Influence of starch and casein administered postruminally on small intestinal sodium-glucose cotransport activity and expression. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 50:963–970. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon D. L. 1992. Dietary influences on carbohydrases and small intestinal starch hydrolysis capacity in ruminants. J. Nutr. 122:203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon D. L. 2009. Understanding starch utilization in the small intestine of cattle. Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. 22:915–922. [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd C. A., Wagner D. G., Hintz R. L., and Griffin D. D.. 1985. Effect of sorghum grain variety and reconstitution on site and extent of starch and protein digestion in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 61:702–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T. M., Schmidt S. P., Russell R. W., Thomas E. E., and Wolfe D. F.. 1991. Comparison of urea treatment with established methods of sorghum grain preservation and processing on site and extent of starch digestion by cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 69:4570–4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington G. B. 1997. Starch utilization by ruminants: From basics to the bunk. J. Anim. Sci. 75:852–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington G. B., and Reynolds P. J.. 1986. Net absorption of glucose, l-lactate, volatile fatty acids, and nitrogenous compounds by bovine given abomasal infusions of starch or glucose. J. Dairy Sci. 69:2428–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes A. N., Weekes T. E. C., and Armstrong D. G.. 1985. Carbohydrase activity in the pancreatic tissue and small intestine mucosa of sheep fed dried-grass or ground maize-based diets. J. Agric. Sci. 104:435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworek J., Nawrot-Porabka K., Leja-Szpak A., and Konturek S. J.. 2010. Brain-gut axis in the modulation of pancreatic enzyme secretion. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 61:523–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., Hurwitz R., and Kretchmer N.. 1977. Adaptation of rat pancreatic amylase and chymotrypsinogen to changes in diet. J. Nutr. 107:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S., Usami M., and Ushijima J.. 1984. The effect of feeding on pancreatic exocrine secretion in sheep. Jap. J. Zootech. Sci. 55:973–977. [Google Scholar]

- Khatim M. S. E. L., and Osman A. M.. 1983. Effect of concentrate feeding on bovine intestinal and pancreatic carbohydrases. Evidence of induced increase in their activities. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 74:275–281. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(83)90600-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konturek S. J., Pepera J., Zabielski K., Konturek P. C., Pawlik T., Szlachcic A., and Hahn E. G.. 2003. Brain-gut axis in pancreatic secretion and appetite control. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Rev. 54:293–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konturek S. J., Radecki T., Thor P., and Dembinski A.. 1973. Release of cholecystokinin by amino acids. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 143:305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krehbiel C. R., Britton R. A., Harmon D. L., Peters J. P., Stock R. A., and Grotjan H. E.. 1996. Effects of varying levels of duodenal or midjejunal glucose and 2-deoxyglucose infusion on small intestinal disappearance and net portal glucose flux in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 74:693–700. doi:10.2527/1996.743693x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreikemeier K. K., and Harmon D. L.. 1995. Abomasal glucose, maize starch and maize dextrin infusions in cattle: small-intestinal disappearance, net portal glucose flux and ileal oligosaccharide flow. Br. J. Nutr. 73:763–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreikemeier K. K., Harmon D. L., Peters J. P., Gross K. L., Armendariz C. K., and Krehbiel C. R.. 1990. Influence of dietary forage and feed intake on carbohydrase activities and small intestinal morphology of calves. J. Anim. Sci. 68:2916–2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Huerou I., Guilloteau P., Wicker C., Mouats A., Chayvialle J. A., Bernard C., Burton J., Toullec R., and Puigserver A.. 1992. Activity distribution of seven digestive enzymes along small intestine in calves during development and weaning. Dig. Dis. Sci. 37:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S. F., Harmon D. L., Vanzant E. S., McLeod K. R., Boling J. A., and Matthews J. C.. 2010. The small intestinal epithelia of beef steers differentially express sugar transporter messenger ribonucleic acid in response to abomasal versus ruminal infusion of starch hydrolysate. J. Anim. Sci. 88:306–314. doi:10.2527/jas.2009-1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S. F., Vanzant E. S., Harmon D. L., McLeod K. R., Boling J. A., and Matthews J. C.. 2009. Ruminal and abomasal starch hydrolysate infusions selectively decrease the expression of cationic amino acid transporter mRNA by small intestinal epithelia of forage-fed beef steers. J. Dairy Sci. 92:1124–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes R. W., and Orskov E. R.. 1974. The utilization of gelled maize starch in the small intestine of sheep. Br. J. Nutr. 32:143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod K. R., Baldwin R. L. VI, El-Kadi S. W., and Harmon D. L.. 2006. Site of starch digestion: Impact on energetic efficiency and glucose metabolism in beef and dairy cattle. In: Cattle Grain Processing Symposium, Oklahoma State University p. 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod K. R., Baldwin R. L. VI, Harmon D. L., Richards C. J., and Rumpler W. V.. 2001. Influence of ruminal and postruminal starch infusion on energy balance in growing steers. In: Chwalibog A. and K. Jakobsen, editors. Energy metabolism in farm animals. Vol. 103 Wageningen (The Netherlands): EAAP Publ, Wageningen Pers; p. 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod K. R., Baldwin R. L. VI, Solomon M. B., and Baumann R. G.. 2007. Influence of ruminal and postruminal carbohydrate infusion on visceral organ mass and adipose tissue accretion in growing beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 85:2256–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchen N. R. 1988. Digestion, absorption and excretion in ruminants. In: Church D. C, editors. The ruminant animal digestive physiology and nutrition. Long Grove (IL): Waveland Press; p. 172–201. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt A. D., and Karn R. C.. 1977. The human alpha-amylases. Adv. Hum. Genet. 8:135–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills J. A. N., France J., Ellis J. L., Crompton L. A., Bannink A., Hannigan M. D., and Dijkstra J.. 2017. A mechanistic model of small intestinal starch digestion and glucose uptake in the cow. J. Dairy Sci. 4650–4670. doi:10.3168/jds.2016–12122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka K., and Funakoshi A.. 1992. Isolation and bioactivity of putative cholecystokinin-releasing peptide from rat small intestinal mucosa. J. Gastroenterol. 27:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran T. H., and Kinzig K. P.. 2004. Gastrointestinal satiety signals II. Cholecystokinin. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 286:G183–G188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill J. S., Kwong L. K., Sunshine P., Briggs G. M., Castillo R. O., and Tsuboi K. K.. 1989. Dietary CHO and stimulation of carbohydrases along villus column of fasted rat jejunum. Am. J. Physiol. 256:G158–G165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayananjalie W. A. D., Wiles T. R., Gerrard D. E., McCann M. A., and Hanigan M. D.. 2015. Acetate and glucose incorporation into subcutaneous, intramuscular, and visceral fat of finishing steers. J. Anim. Sci. 93:2451–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle. 8th rev. ed Washington (DC): The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/19014 [Google Scholar]

- Nilaweera K. N., Giblin L., and Ross R. P.. 2010. Nutrient regulation of enteroendocrine cellular activity linked to cholecystokinin gene expression and secretion. J. Physiol. Biochem. 66:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi T., Hara H., and Tomita F.. 2003. The soybean beta-conglycinin beta 51–63 fragment suppresses appetite by stimulating cholecystokinin release in rats. J. Nutr. 133:2537–2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsi-Emvo E., Foltzer-Jourdainne C., Raul F., Gosse F., Duluc I., Koch B., and Freund J. N.. 1994. Precocious and reversible expression of sucrase-isomaltase unrelated to intestinal cell turnover. Am. J. Physiol. 266:G568–G575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orskov E. R. 1976. The effect of processing on digestion and utilization of cereals by ruminants. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 35:245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orskov E. R., Fraser C., and Kay R. N.. 1969. Dietary factors influencing the digestion of starch in the rumen and small and large intestine of early weaned lambs. Br. J. Nutr. 23:217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orskov E. R., Fraser C., Mason V. C., and Mann S. O.. 1970. Influence of starch digestion in the large intestine of sheep on caecal fermentation, caecal microflora and faecal nitrogen excretion. Br. J. Nutr. 24:671–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens C. E., Zinn R. A., Hassen A., and Owens F. N.. 2016. Mathematical linkage of total-tract digestion of starch and neutral detergent fiber to their fecal concentrations and the effect of site of starch digestion on extent of digestion and energetic efficiency of cattle. Prof. Anim. Sci. 32:531–549. doi:10.15232/pas.2016-01510. [Google Scholar]

- Owens F. N., Zinn R. A., and Kim Y. K.. 1986. Limits to starch digestion in the ruminant small intestine. J. Anim. Sci. 63:1634–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappenheimer J. R. 1993. On the coupling of membrane digestion with intestinal absorption of sugars and amino acids. Am. J. Physiol. 265:G409–G417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov I. P. 1898. Die arbeit der verdauungsdrusen. Bergmann, Wiesbaden, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Richards C. J., Branco A. F., Bohnert D. W., Huntington G. B., Macari M., and Harmon D. L.. 2002. Intestinal starch disappearance increased in steers abomasally infused with starch and protein. J. Anim. Sci. 80:3361–3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards C. J., Swanson K. C., Paton S. J., Harmon D. L., and Huntington G. B.. 2003. Pancreatic exocrine secretion in steers infused postruminally with casein and cornstarch. J. Anim. Sci. 81:1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riepl R. L., Fiedler F., Ernstberger M., Teufel J., and Lehnert P.. 1996. Effect of intraduodenal taurodeoxycholate and L-phenylalanine on pancreatic secretion and on gastroenteropancreatic peptide release in man. Eur. J. Med. Res. 1:499–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S. M., Guimaraes K. C., Matthews J. C., McLeod K. R., Baldwin R. L. VI, and Harmon D. L.. 2004. Influence of abomasal carbohydrates on small intestinal sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter activity and abundance in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 82:3015–3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. R., Young A. W., and Jorgensen N. A.. 1981. Effect of dietary corn starch intake on pancreatic amylase and intestinal maltase and pH in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 52:1177–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sale J. K., Goldberg D. M., Fawcett A. N., and Wormsley K. G.. 1977. Chronic and acute studies indicating absence of exocrine pancreatic feedback inhibition in dogs. Digestion. 15:540–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick J., Verspohl R., Kern H., and Scheele G.. 1984. Two distinct adaptive responses in the synthesis of exocrine pancreatic enzymes to inverse changes in protein and carbohydrate in the diet. Am. J. Physiol. 247:G611–G616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi-Beechey S., Hirayama B., Wang Y., Scott D., Smith M., and Wright E.. 1991. Ontogenic development of lamb intestinal sodium-glucose cotransporter is regulated by diet. J. Physiol. 437:699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi-Beechey S. P., Moran A. W., Batchelor D. J., Daly K., and Al-Rammahi M.. 2011. Glucose sensing and signalling; regulation of intestinal glucose transport. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 70:185–193. doi:10.1017/S0029665111000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddons R. C. 1968. Carbohydrase activities in the bovine digestive tract. Biochem. J. 108:839–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. B., and Crouse J. D.. 1984. Relative contributions of acetate, lactate and glucose to lipogenesis in bovine intramuscular and subcutaneous adipose tissue. J. Nutr. 114:792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snook J. T. 1971. Dietary regulation of pancreatic enzymes in the rat with emphasis on carbohydrate. Am. J. Physiol. 221:1383–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Jean G., Harmon D., Peters J., and Ames N.. 1992. Collection of pancreatic exocrine secretions by formation of a duodenal pouch in cattle. Am. J. Vet. Res. 53:2377–2380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson K. C., Benson J. A., Matthews J. C., and Harmon D. L.. 2004. Pancreatic exocrine secretion and plasma concentration of some gastrointestinal hormones in response to abomasal infusion of starch hydrolyzate and/or casein. J. Anim. Sci. 82:1781–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson K. C., Kelly N., Salim H., Wang Y. J., Holligan S., Fan M. Z., and McBride B. W.. 2008. Pancreatic mass, cellularity, and a-amylase and trypsin activity in feedlot steers fed diets differing in crude protein concentration. J. Anim. Sci. 86:909–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson K. C., Matthews J. C., Woods C. A., and Harmon D. L.. 2002. Postruminal administration of partially hydrolyzed starch and casein influences pancreatic alpha-amylase expression in calves. J. Nutr. 132:376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K., Huntington G. B., and Glenn B. P.. 1995. Net nutrient flux by visceral tissues of beef steers given abomasal and ruminal infusions of casein and starch. J. Anim. Sci. 73:236–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theurer C. B. 1986. Grain processing effects on starch utilization by ruminants. J. Anim. Sci. 63:1649–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titgemeyer E. C. 1997. Design and interpretation of nutrient digestion studies. J. Anim. Sci. 75:2235–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker R. E., Mitchell G. E. Jr., and Little C. O.. 1968. Ruminal and postruminal starch digestion in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 27:824–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beers E. H., Buller H. A., Grand R. J., Einerhand A. W. C., and Dekker J.. 1995. Intestinal brush border glycohydrolases: structure, function, and development. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30:197–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhorst M., Smeets A., Soenen S., Hochstenbach-Waelen A., Hursel R., Diepvens K., Lejeune M., Luscombe-Marsh N., and Westerterp-Plantenga M.. 2008. Protein-induced satiety: effects and mechanisms of different proteins. Physiol. Behav. 94:300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Prpic V., Green G. M., Reeve J. R. Jr., and Liddle R. A.. 2002. Luminal CCK-releasing factor stimulates CCK release from human intestinal endocrine and STC-1 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 282:G16–G22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., and Taniguchi K.. 1998. Activity of pancreatic digestive enzyme in sheep given abomasal infusion of starch and casein. Anim. Sci. Technol. 69:870–874. [Google Scholar]

- Wright E. M. 1993. The intestinal Na+/glucose cotransporter. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 55:575–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright E. M., Hirayama B. A., Loo D. D. F., Turk E., and Hager K.. 1994. Intestinal sugar transport. In: E. R., Johnson, editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract, 3rd ed New York, NY: Raven Press; p. 1751–1772. [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. 2010. Functional amino acids in growth, reproduction, and health. Adv. Nutr. 1:31–37. doi:10.3945/an.110.1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabielski R. 2003. Luminal CCK and its neuronal action on exocrine pancreatic secretion. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 54:81–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabielski R., Kiela P., Lesniewska V., Krzeminski R., Mikolajczyk M., and Barej W.. 1997. Kinetics of pancreatic juice secretion in relation to duodenal migrating myoelectric complex in preruminant and ruminant calves fed twice daily. Br. J. Nutr. 78:427–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]