Abstract

Piglet vocalization rates are used as welfare indicators. The emission rates of the two gross categories of piglet calls, namely low frequency calls (“grunts”) and high frequency calls (“screams”), may contain different information about the piglet’s internal state due to differing communicative functions of the two call types. More knowledge is needed about the sources of variation in calling rates within and between piglets. We examined to what extent the emission rates of the two call types are codetermined by individual and litter identity, i.e., whether the rates are repeatable within individuals and similar between littermates. We recorded frequency of grunts and screams in one mildly negative (short-term Isolation) and one moderately negative (manual Restraint) situation during the first week (week 1) and the 4th week (week 4) of life and asked the following questions: 1) Are within-individual vocalization rates stable across the suckling period? 2) Are within-individual vocalization rates stable across the two situations? 3) Is there within-litter similarity in vocalization rates? 4) Does this within-litter similarity increase during the suckling period? Within-individual vocalization rates were stable between week 1 and week 4 (grunts in Restraint P < 0.05; grunts in Isolation P < 0.001; screams in Restraint P < 0.001; screams in Isolation P < 0.001). Across the two situations at the same age, the vocalization rates were not stable for grunts but were stable for screams at week 1 and week 4 (P < 0.05). Vocalization rates were more similar between littermates than between piglets belonging to different litters (grunts in Restraint P < 0.001; grunts in Isolation P < 0.01; screams in Restraint P < 0.001; screams in Isolation P < 0.001). This litter effect did not grow stronger from week 1 to week 4 as the within-litter coefficient of variance did not decrease between the two ages. Sex of the piglet had no influence on vocalization rates while greater body weight was associated with lower screaming rates in the Restraint situation (P < 0.05). In conclusion, our study demonstrates that both individuality of the piglet and litter identity affect the vocalization rates of piglets in negatively valenced situations. For screams, the repeatability of individual vocalization rates holds even across situations, while for grunts, the rates are repeatable during ontogeny within the situations, but not across situations.

Keywords: individual differences, ontogeny, preweaning piglets, vocalization

INTRODUCTION

In piglets, vocalization rates have been utilized as indicators of compromised welfare (Weary and Fraser, 1997; Taylor and Weary, 2000; Marchant-Forde et al., 2009, 2014). When quantifying vocal activity, it is important to distinguish between various call types as they may carry different information about the animal’s subjective state (Illmann et al., 2013). Preweaning piglets produce two broad categories of calls (Tallet et al., 2013). Low-frequency “grunts” are produced during periods of moderate to high arousal, while high-frequency “scream” calls are emitted in situations of urgent discomfort such as pain, restraint, prolonged isolation, or fighting for a teat (Kiley, 1972). In the context of distress, such as when isolated or manually restrained, piglets produce call series with various proportions of grunts and screams (Puppe et al., 2005; Linhart et al., 2015).

Vocalization rates are influenced not only by the current subjective state, but also by other factors, including the personality profile of individual animals. In postweaning pigs, some individuals are steadily more vocal than others (Friel et al., 2016). It has never been investigated in preweaning piglets whether individual differences in vocalization rates are stable over the duration of the suckling period or across situations and if so, whether the stability applies both to high- and low-frequency calls. The aim of this study was to quantify within-individual stability in the emission rates of grunts and screams by preweaning piglets in two negative situations (Restraint and Isolation). Specifically, we investigated the following questions: 1) Are within-individual vocalization rates stable across the suckling period? 2) Are within-individual vocalization rates stable between the Isolation and the Restraint situations? 3) Is there within-litter similarity in vocalization rates? 4) Does this within-litter similarity increase during the suckling period?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experiment was conducted in accordance with the valid Czech laws and regulations, in compliance with the Ethic Committee of the Institute of Animal Sciences, Prague – Uhříněves. The study was performed under accreditations no. 60444/2011-MZE-17214 and 18480/2016-MZE-17214.

Place and Animals

The experiment was accomplished at the Netluky pig farm owned by the Institute of Animal Science in Prague (Czech Republic) during the years 2014 and 2015. The mother sows were Large White × Landrace pigs housed in standard farrowing pens 2.3 × 2 m with a crate. The sows were provided with ad-libitum lactating sow feed and water while the piglets had continuous access to a heated nest, creep formula feed (starting from day 10 of life) and a nipple drinker. We used piglets from 13 litters (Large White × Landrace) × (Duroc × Pietrain) within median litter size of 11 piglets (range 7 to 16) at the age of the first testing (see below). We aimed at testing 10 piglets from each litter, or the maximum number available in litters with less than 10 piglets. However, piglets that were sick, injured, and severely underweight at the moment of the respective test were excluded from testing. The analysis was then based on all the 91 piglets (50 females, 41 males) for which data from all four tests were obtained. Male piglets were castrated within a few days after the first testing, resulting in a period of at all 18 d between the castration and the second testing. All piglets were marked with a unique ear tag and weighed on the days of testing.

Testing and Recording

All piglets were tested first at the age of 3 to 7 d (week 1) and then before weaning (at 25 to 30 d, week 4). The variation in age at testing was caused by a necessity to avoid days when husbandry procedures such as castration or weaning occurred at the farm that could have affected the emotional states of the piglets. At both week 1 and week 4, each piglet was recorded in two different situations: in Isolation and in Restraint. For the tests, piglets were individually taken from the mother within 20 min after the last nursing to avoid them being hungry during the testing. Experiments took place in a separate room, thus piglets were affected neither by the presence nor the sounds of other piglets or sows. Piglets in Isolation were recorded for 1 min in a wooden box (0.5 m × 0.5 m × 0.5 m) and after that they were turned on their back and held for 1 min on a flat surface (Restraint test) and simultaneously recorded. We used an Olympus recorder (Linear PCM recorder LS-12) in all experiments. The recorder was placed one meter above the floor of the isolation box or 1 m from the snout of the piglet in the case of the Restraint test. All piglets were placed back with the sow and littermates immediately after the recordings were finished. From the recordings, two classes of vocalizations were distinguished based on mean peak frequency (Puppe et al., 2005) and counted separately, namely low-frequency calls (“grunts”, <1,000 Hz) and high-frequency calls (“screams”, >1,000 Hz).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R (R Core Team, 2016). Individual stability of vocalization rates across weeks was tested using Pearson correlation coefficient in the case of grunts in Restraint, grunts in Isolation, and screams in Restraint. Repeatability of vocalization rates between situations (e.g., grunts in week 1 across Restraint and Isolation) was also tested using Pearson correlations. In the case of screams in Isolation, many piglets did not emit any screams and thus we divided piglets in two groups that did/did not emit screams. Next, we assessed with chi-square test whether piglets that screamed in Isolation in week 1 were more likely to scream in week 4 (repeatability of Isolation screaming rates during ontogeny). Further we used t-test to compare whether piglets that emitted screams in Isolation screamed more during Restraint than piglets that did not emit any screams in Isolation (repeatability of screaming rate across situations).

To assess whether vocalization rates of piglets were more similar within a litter, we considered each of the four call type × situation combinations separately. We ran generalized linear mixed-effect models (“lmer” and “glmer” functions) using “lme4” package (Bates et al., 2015) to assess the fixed effects of age (week 1/week 4), sex, and body weight on vocalization rates. Body weight entered the models as logarithmized deviations from the average weight at the given week as we wanted to have the weight as orthogonal, rather than correlated with week. Identity of piglet and litter were entered as random factors. In preliminary analyses, we also included litter size and exact piglet age (as a deviation from average age at week 1 and week 2 testing), but as neither of these factors affected vocalization rates, they were not included in the final models. Package “lme4” does not estimate degrees of freedom and significances for fixed and random factors. Therefore, significances of the fixed effects of “week” and “sex” factors as well as significance of “litter” random factor were obtained by comparing models with and without each factor. For the model of screams in Isolation data, we used presence of screaming (1/0) and binomial distribution (logit link function), instead of scream counts because many piglets did not scream in Isolation. For the other three models (grunts in Restraint, grunts in Isolation, screams in Restraint) we did not use any transformation of data and used number of vocalization as a response variable (identity link function). We visually inspected model residuals to confirm model assumptions in these cases.

Finally, to evaluate whether vocalization rates of piglets from one litter become more similar during ontogeny, we computed coefficients of variations (CV) of vocalization rates for piglets within each litter and used paired t-test to compare CVs in week 1 and week 4. This has been done for three of the four combinations of situation and call type. For screams in Isolation, it was not possible due to the fact that many piglets did not emit any screams.

RESULTS

Individual Stability of Vocalization Rates

Within the Isolation and the Restraint situation, within-individual vocalization rates were significantly stable during ontogeny (Figure 1) for both grunting and screaming (grunts in Restraint: r = 0.261, df = 84, P < 0.05; grunts in Isolation: r = 0.403, df = 84, P < 0.001; screams in Restraint: r = 0.543, df = 84, P < 0.001; screams in Isolation: χ2 = 13.85, df = 1, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Relationships between individual vocalization rates at week 1 and week 4 for grunts in Restraint (a), grunts in Isolation (b), screams in Restraint (c), and screams in Isolation (d). Linear regression lines were added to illustrate trends (a–c). For screams in Isolation (d), the heights of the bars represent the number of piglets that screamed in week 1 (Yes—left bar, No—right bar), while colors represent how many piglets screamed in week 4 (Yes—gray, No—white). For instance, there were five piglets that did not scream in week 1 but screamed in week 4.

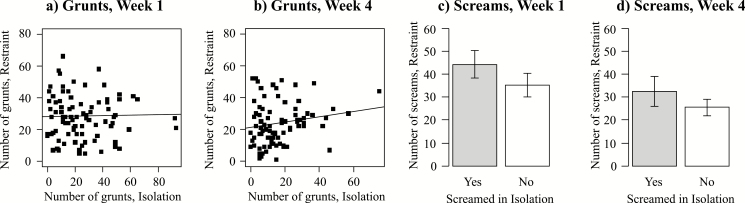

Across the two situations, the within-individual vocalization rates followed a different pattern for grunts and for screams. Individual grunting rates did not correlate between Isolation and Restraint either at week 1 (r = 0.025, df = 84, P = 0.822) or at week 4 (r = 0.170, df = 84, P = 0.118). To the contrary, individual propensity to scream was related across the two situations (Figure 2), as those piglets that screamed at least once in Isolation produced more screams during Restraint at both week 1 (t = −2.350, df = 84, P < 0.05) and week 4 (t = −1.998, df = 84, P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Relationships between vocalization rates in Isolation and in Restraint for grunts at week 1 (a), grunts at week 4 (b), screams at week 1 (c), and screams at week 4 (d). Linear regression lines were added to illustrate trends (a, b). Means and 95% confidence intervals are presented (c, d).

Effects of Age, Weight, Sex, and Litter

Vocalization rate decreased from week 1 to week 4 for both grunts and screams in both situations (Figure 3; grunts in Restraint: F = 5.89, P = 0.017; grunts in Isolation: F = 21.23, P < 0.001; screams in Restraint: F = 45.08, P < 0.001; screams in Isolation: F = 8.05, P = 0.008).

Figure 3.

Effect of age on vocalization rates (numbers of calls, proportion of piglets emitting screams) of piglets during Restraint (a, c) and Isolation (b, d). Means and 95% confidence intervals (a–c) and proportion of piglets emitting scream and 95% confidence intervals (d) are presented.

Greater body weight was associated with lower screaming rates in the Restraint situation (Figure 4, F = 6.43, P = 0.011). No other combination of situation with call type was influenced by body weight (grunts in Restraint F = 2.40, P = 0.130; grunts in Isolation F = 0.39, P = 0.521; screams in Isolation F = 1.65, P = 0.218).

Figure 4.

Illustration of the effect of weight on screaming rate during Restraint situation. Weight residuals are residuals from linear regression of common logarithm of weight on age. Data for week 1 and week 4 are plotted together. A simple linear regression line is added to illustrate the overall trend (y = −28.7x + 33.6).

There was no effect of piglet sex on the number of grunts or screams emitted in either situation (all P’s > 0.45).

The litter identity effect proved significant on vocalization rates in all cases, namely for grunting during Restraint (P < 0.001), grunting in Isolation (P < 0.01), screaming during Restraint (P < 0.001), and screaming in Isolation (P < 0.001). That is, vocalization rates were more similar between littermates than between piglets belonging to different litters.

This litter effect did not grow stronger from week 1 to week 4 as the within-litter coefficient of variance did not decrease between the two ages (grunts in Isolation: t = −1.157, df = 12, P = 0.270; grunts in Restraint: t = −0.119, df = 12, P = 0.908; screams in Restraint: t = −0.583, df = 12, P = 0.571).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of our study is that vocalization rates were individually stable, thus producing interindividual differences that contributed significantly to the overall variability in piglet vocalization rates during negatively valenced situations. The first aspect of the individual stability in signaling rates is in the ontogenetic dimension. The individual vocalization rates during the first week of life correlated with vocalization rates of the same individuals before weaning. This was true for both types of calls in either of the two situations. It needs to be noted, though, that the correlations between vocalization rates at week 1 and week 4 were weak to moderate, especially for grunts, and thus only a minor proportion of overall variability in vocalization rates was explained by the ontogenetically stable individual differences.

The second aspect of the individual differences in vocalization rates concerns the stability across different situations. In our study, individual stability in vocalization rates across the two situations was found for screams, but not for grunts. This difference may be explained by the different functions of the two types of calls. Screams are considered to communicate the perceived severity of distress by the calling pig (Marx et al., 2003; Linhart et al., 2015). Therefore, more stress-prone individuals may emit more screams in the restraint situation and also be inclined to produce screams in the (much less negative) situation of Isolation, which is what we found in this study. In contrast to screams, grunts are contact calls rather than emergency signals (Garcia et al., 2016). As such, emission of grunts may be less dictated by individual stress-sensitivity and therefore the grunting rate in one situation may be unrelated to the grunting rate in another.

Our results are in agreement with a recent study on postweaning pigs at the age of 6 to 8 wk (Friel et al., 2016). Friel et al. found that emission rates of low-frequency calls were repeatable over the examined 2-wk period and also across two testing situations, namely social isolation and novel object test. Our study covered an earlier ontogenetic period and included two types of calls. A further difference is that Friel et al. investigated the vocal activity in two situations that were quite similar to each other (isolation without and with a novel object), while the two situations in our study (isolation and restraint by hand) caused very different distress levels in the pigs, as documented by the large difference in screaming rate. Our study is thus the first to show in pigs that repeatability in calling rates is already present in the first weeks of life and that it applies to situations widely differing in the intensity of negative emotional valence.

While the relative differences in vocalization rates between piglets persevered over the preweaning period, the average rates declined from week 1 to week 4. One explanation for this decline in acoustic signaling may be that older piglets need less maternal care and protection due to their better thermoregulation and more advanced body development and thus they are less likely to convey information about their negative situation to the mother. Another possibility is that lower vocalization rates at week 4 were due to habituation to the testing procedure, although this does not seem very plausible given that 3 wk occurred between the first and the second exposure of the piglets to the tests. Finally, the everyday contact with people due to husbandry activities might have habituated the piglets to any human contact, including the testing. However, that explanation would only apply to the Restraint and not to the Isolation in which no human contact was involved.

Body weight was negatively related to rates of scream emission during restraint, but none of the other three situation and vocalization type combinations was affected by body weight. In a previous study (Illmann et al., 2013), we found that lighter piglets vocalized more frequently in a situation that simulated (with a 5 kg hand pressure) being trapped under the sows body. The current results show that even in a less stressful situation (being restrained but not pressured), lighter piglets signal more frequently, possibly because they are in greater need of help by an action of the mother. Both studies agree that piglet vocalization rates in a negative yet much less threatening situation of short-term isolation are unaffected by piglet body weight.

Our data also show that vocalization rates of piglets from the same litter were more similar to each other than the vocalization rates of piglets from different litters. The within-litter similarity in vocalization rates was a strong phenomenon in our data as we found it in all four combinations of situation and vocalization type. This within-litter similarity could be due to genetic relatedness of the siblings, effects of common prenatal environment, or common postnatal effects. The postnatal effects could include mutual social learning as piglets are responsive to each other’s vocalizations, e.g., when they synchronously attempt to initiate a nursing from their mother. However, in our study, there was no increase in the litter effect over the suckling period. Thus, the within-litter similarity was already fully established in the first week of life of the piglets, pointing to a genetic, prenatal, or early ontogenetic cause of this phenomenon.

The current results complement our recent finding (Syrová et al., 2017) that preweaning piglets individually differ in the acoustic properties of their vocalization and that vocalization of piglets from the same litter are acoustically more similar to each other than vocalization of piglets from another litter. In combination, the two studies indicate that piglets possess individual vocal profiles that are expressed in both how much they call and how the calls are structured, and that these profiles are similar among litter-mates.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that both individuality of the piglet and litter identity affect the vocalization rates of piglets in negatively valenced situations. For the high-frequency vocalizations, the repeatability of individual vocalization rates holds even across situations, while for the low-frequency grunts, the rates are repeatable during ontogeny within the situations, but not across the situations. These findings need to be taken into account when vocalization rates are used as indicators of arousal, emotional states or welfare.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Czech Science Foundation (grant number 14-27925S), Czech Ministry of Agriculture (grant number MZERO0717), and Grant Agency of the University of South Bohemia (GAJU 04-151/2016/P). We would like to thank Vladimír Němeček, Miroslav Král, and Lydie Máchová for their collaboration during the experiments.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., and Walker S.. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67:1–48. doi:10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [Google Scholar]

- Friel M., Kunc H. P., Griffin K., Asher L., and Collins L. M.. 2016. Acoustic signaling reflects personality in a social mammal. R. Soc. Open. Sci. 3:160178. doi:10.1098/rsos.160178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M., Gingras B., Bowling D. L., Herbst C. T., Boeckle M., Locatelli Y., and Fitch W. T.. 2016. Structural classification of wild boar (Sus scrofa) vocalizations. Ethol. 122:329–342. doi:10.1111/eth.12472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illmann G., Hammerschmidt H., Špinka M., and Tallet C.. 2013. Calling by domestic piglets during simulated crushing and isolation: signal of need?PLoS One 8:e83529. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiley M. 1972. The vocalizations of ungulates, their causation and function. Z. Tierpsychol. 31:171–222. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1972.tb01764.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhart P., Ratcliffe V. F., Reby D., and Špinka M.. 2015. Expression of emotional arousal in two different piglet call types. PLoS One. 10:e0135414. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant-Forde J. N., Lay D. C. Jr., McMunn K. A., Cheng H. W., Pajor E. A., and Marchant-Forde R. M.. 2009. Postnatal piglet husbandry practices and well-being: the effects of alternative techniques delivered separately. J. Anim. Sci. 87:1479–1492. doi:10.2527/jas.2008-1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant-Forde J. N., Lay D. C., McMunn K. A., Cheng H. W., Pajor E. A., and Marchant-Forde R. M.. 2014. Postnatal piglet husbandry practices and well-being: the effects of alternative techniques delivered in combination. J. Anim. Sci. 92:1150–1160. doi:10.2527/jas.2013–6929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx G., Horn T., Thielebein J., Knubel B., and von Borell E.. 2003. Analysis of pain-related vocalization in young pigs. J. Sound Vibration. 266:687–698. doi:10.1016/S0022-460X(03)00594-7 [Google Scholar]

- Puppe B., Schon P. C., Tuchscherer A., and Manteuffel G.. 2005. Castration-induced vocalisation in domestic piglets, Sus scrofa: complex and specific alterations of the vocal quality. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 95:67–78. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.05.001 [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2016. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Syrová M., Policht R., Linhart P., and Špinka M.. 2017. Ontogeny of individual and litter identity signaling in grunts of piglets. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 142:3116–3121. doi:10.1121/1.5010330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallet C., Linhart P., Policht R., Hammerschmidt K., Šimeček P., Kratinová P., and Špinka M.. 2013. Encoding of situations in the vocal repertoire of piglets (Sus scrofa): a comparison of discrete and graded classifications. PLoS One 8:e71841. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. A., and Weary D. M.. 2000. Vocal responses of piglets to castration: identifying procedural sources of pain. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 70:17–26. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(00)00143-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weary D. M., and Fraser D.. 1997. Vocal response of piglets to weaning: effect of piglet age. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 54:153–160. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(97)00066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]