Abstract

Heat stress (HS) and immune challenges negatively impact nutrient allocation and metabolism in swine, especially due to elevated heat load. In order to assess the effects of HS during Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) infection on metabolism, 9-wk old crossbred barrows were individually housed, fed ad libitum, divided into four treatments: thermo-neutral (TN), thermo-neutral PRRSV infected (TP), HS, and HS PRRSV infected (HP), and subjected to two experimental phases. Phase 1 occurred in TN conditions (22 °C) where half the animals were infected with PRRS virus (n = 12), while the other half (n = 11) remained uninfected. Phase 2 began, after 10 d with half of the uninfected (n = 6) and infected groups (n = 6) transported to heated rooms (35 °C) for 3 d of continuous heat, while the rest remained in TN conditions. Blood samples were collected prior to each phase and at trial completion before sacrifice. PPRS viral load indicated only infected animals were infected. Individual rectal temperature (Tr), respiration rates (RR), and feed intakes (FI) were determined daily. Pigs exposed to either challenge had an increased Tr, (P < 0.0001) whereas RR increased (P < 0.0001) with HS, compared to TN. ADG and BW decreased with challenges compared to TN, with the greatest loss to HP pigs. Markers of muscle degradation such as creatine kinase, creatinine, and urea nitrogen were elevated during challenges. Blood glucose levels tended to decrease in HS pigs. HS tended to decrease white blood cell (WBC) and lymphocytes and increase monocytes and eosinophils during HS. However, neutrophils were significantly increased (P < 0.01) during HP. Metabolic flexibility tended to decrease in PRRS infected pigs as well as HS pigs. Fatty acid oxidation measured by CO2 production decreased in HP pigs. Taken together, these data demonstrate the additive effects of the HP challenge compared to either PRRSV or HS alone.

Keywords: heat stress, metabolism, pig, PRRSV

INTRODUCTION

Increased global temperature and global populations have resulted in more people living in tropical or subtropical locations (Renaudeau et al., 2012; Pachauri et al., 2014). The increased temperature index due to these shifts is detrimental to animal agriculture, especially in pigs that lack functional sweat glands to alleviate the heat load resulting in heat stress (HS). HS however, is not the only detrimental factor to the swine industry. Pigs often suffer from pathogen challenges that can be bacterial or viral infections. Of these pathogens, Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) is one of the most antagonistic pathogens plaguing the industry and has an estimated annual economic impact of over $560 million (Neumann et al., 2005). Economic estimates of PRRS account for decreased reproductive health, increased death, and reduction in the efficiency of growth (Neumann et al., 2005).

During immune and heat challenges, feed intake can be reduced, with nutrient repartitioning toward immune responses and heat alleviation, respectively. The decreased nutrient availability reduces muscle growth and increases production cycle length. Muscle accretion decreases and muscle degradation increases during both challenges in order to provide amino acids in support of acute phase protein and heat shock protein synthesis (Johnson, 1997; Rhoads et al., 2013). Opposing effects are seen during HS compared to immune challenge with respect to increased lipid retention (Rhoads et al., 2009) verse increased lipid mobilization, respectively (Webel et al., 1997). Moreover, HS alters metabolism differently than typical metabolic profiles related to plane of nutrition and energy balance (Baumgard and Rhoads, 2013). This implies that immune challenge and HS could potentially be affecting metabolism in an opposite manner.

Developing a strategy to mitigate the effects of immune and HS challenges on production requires a better understanding of how multiple stresses may affect production, nutrient allocation, and metabolism. The objective of this study was to determine effects of HS during PRRSV infection on production and metabolism in pigs. We hypothesized the combined HS and PRRSV infection would be more detrimental to growth and metabolism than either challenge alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Treatment

The Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures involving animals. All animals were housed in an Animal Biosafety Level 2 facility with independent ventilation systems and temperature control, and controlled entry into each of four identical rooms. Animals (crossbred barrows; n = 24) were purchased from a PRRSV free, commercial farm (Murphy-Brown, Roanoke, VA) at 6 wk of age with initial BW of 30.1 kg. Upon receipt of the pigs at Virginia Tech, blood samples were collected and tested for the presence of PRRSV antibody using a commercial ELISA kit (HerdChek PRRS 3X ELISA; IDEXX Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, ME) as described previously (Li et al., 2015). All pigs tested negative. Animals were housed in individual pens equipped with feeders and waters throughout the study. Upon receipt, the animals were placed into two of the rooms (12 pens per room) at thermo-neutral conditions (22 °C) with a 12:12 (L:D) h cycle, and fed an antibiotic free commercial diet ad libitum that provided adequate levels of all essential nutrients (Table 1) for 3 wk. Pigs had ad libitum access to water. Prior to initiation of treatments, animals (n = 24) were weighed and randomly assigned to one of four treatments based on BWs in a 2 × 2 factorial design. The treatments consisted of: 1) thermo-neutral (TN) conditions (22 °C ± 1 °C; 30% to 50% relative humidity), 2) TN + PRRSV infection (TP), 3) HS conditions (constant 35 °C ± 1 °C; 20% to 40% relative humidity), and 4) HS + PRRSV infection (HP).

Table 1.

Ingredients (DM basis) and chemical composition of diet

| Items | Content |

|---|---|

| Ingredient | % of AFa |

| Corn | 59.61 |

| Soybean meal | 28.30 |

| Distiller dried grains | 5.00 |

| Lard | 1.69 |

| Blood meal | 1.50 |

| Ground limestone | 1.21 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.18 |

| Lysine 78.8% | 0.360 |

| Salt (plain) | 0.350 |

| Vitamin/mineral premixb | 0.150 |

| DL-Methionine | 0.150 |

| L-Threonine 98.5% | 0.100 |

| Selenium premix (0.06%) | 0.037 |

| Choline chloride (60%) | 0.075 |

| Maxi-MIL HP Binderc | 0.050 |

| Bacitracin (132 g/kg) | 0.208 |

| Ronozyme P-CTd | 0.025 |

| Formulated nutrients | % of AF |

| ME, kcal/kg | 2,961 |

| CP | 21.29 |

| Crude fat | 5.0 |

| Ca | 0.85 |

| Total P | 0.57 |

| Lysine | 1.43 |

| Methionine | 0.47 |

| Methionine+ cystine | 0.79 |

| Threonine | 0.87 |

aAF = air-dried feed.

bProvided per kilogram of diet AF: 348 mg Zn, 397 mg Fe, 54 mg Cu, 1.3 mg I, 157 mg Mn, 11,015 IU vitamin A, 1,764 IU vitamin D, 122 IU vitamin E, 70 mg niacin, 30 mg pantothenic acid, 0.40 mg biotin, 1.6 g choline, 2.1 mg folic acid, and 4.4 mg pyridoxine.

cAnatox, Lawrenceville, GA.

dNovozymes, Bagsværd, Denmark.

During the acclimation phase one pig was removed from the trial due to injury, resulting in one less pig (n = 5) in the TN control group, whereas all other treatments (TP, HS, HP) had n = 6 per treatment. The experiment was divided into two periods based on experimental conditions: 1) infection (day 1–11) and 2) HS (day 11–14). Day 1 marked the beginning of the trial with the differentiation of the two TN rooms into noninfected and infected. The pigs designated for infection were inoculated intramuscularly with 1 mL of PRRSV (VR-2385; 1 × 104 50% tissue culture infectious dose/ml; kindly provided by Dr. X.J. Meng, Virginia Tech and prepared as described previously, Piñeyro et al., 2015). The route of administration and infection time-course have been validated previously (Hermann et al., 2005; Li et al., 2015; Piñeyro et al., 2015). Room entry was controlled to ensure that PRRSV was not transferred to the noninfected room. On day 11, pigs assigned to the HS treatments were moved in their stalls into two preheated rooms (35 °C), while the rest remained in thermo-neutral conditions. On day 14 after 3 d of constant heat, all animals were sacrificed for sample collection. Each room’s temperature and humidity were measured (Acurite model Thermo Hygro, Bellingham, WA) and recorded at 6:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. An electric forced air heater (Model F3F551QT, TPI Corporation) with constant circulation maintained the HS room temperatures and humidity was not governed. Room temperature was maintained under the control of a computer system (Siemens Building Automation System) and recorded in 30-min intervals. All animals were monitored for signs of distress throughout the experiment by measuring rectal temperature and respiration rates as described previously (Pearce et al., 2013a; 2013b). Rectal temperature and respiration rates were measured twice daily (6:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m.) or thrice daily during the 3-d HS period (6:00 a.m., 12:00 p.m., 5:00 p.m.). Rectal temperatures were taken with a digital thermometer (Welch Alleyn Sure Temp PLUS, Skaneateles Falls, NY) and respiration rates (breaths/min) measured by visual observation with a stopwatch. If body temperature rose above 40.5 °C the pigs were hosed down with cool water for 2 min and their temperature retaken. If the temperature was still elevated pigs, were removed from the room for 5 min or until body temperature decreased below 40.5 °C as described previously (Pearce et al., 2013a). During this cooling period the pigs had access to water. Pigs were fed ad libitum and feed intake was recorded once daily (6:00 a.m.). BWs were taken (6:00 a.m.) every 3 d (Way Pig 300, Raytec Manufacturing, Schuyler, NE), including on days 1, 11, and 14.

Jugular vein blood samples were collected into vacutainers containing lithium heparin or a silicone coat (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) on day 1 prior to inoculation, day 11 prior to environmental treatment, and day 14 prior to sacrifice. After blood samples were collected on day 14 the pigs were euthanized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital followed by exsanguination.

All tissues were harvested within 10 min postmortem and included: Longissimus Dorsi muscle and liver. The Longissimus Dorsi was excised using aseptic technique, a sample was taken for immediate metabolic analysis and the rest was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until analysis. A liver sample was taken and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Metabolite Assays

Plasma was aliquoted into three 2 mL tubes, two stored at −20 °C and one was sent to the Virginia Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine Diagnostic Laboratory for analysis of creatine kinase (CK), creatinine, urea nitrogen, and glucose. All plasma samples were analyzed with the Beckman Coulter AU480 (Brea, CA). Serum was allowed to coagulate at room temperature for 1 h before centrifuging at 4 °C for 20 min at 1,425 × g. Serum was aliquoted into 2 mL micro-centrifuge tubes and stored: one sample at −80 °C for qPCR and the rest at −20 °C. A additional sample of jugular vein blood was collected on day 14 into a vacutainer containing K2EDTA and sent to the Virginia Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine Diagnostic Laboratory for complete blood count (CBC) analysis. Serum samples were analyzed with a Siemens Advia 2120 (Malvern, PA).

Viral Load Determination

PRRSV plasmid pACYC VR2385 was kindly provided by Dr. X.J. Meng (CRC, Virginia Tech). The plasmid was transformed into E. coli MACH-1 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with Kanamycin antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Colonies were picked and incubated in LB Broth in the orbital shaker (Thermo Scientific MaxQ4450, Rockford, IL) at 37 °C for 16 h. Plasmid DNA was extracted using the Qiagen Mini Prep Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A Nanophotometer Pearl (Implen, Westlake Village, CA) was used to determine purity and concentration of DNA. DNA was stored in a −20 °C freezer.

The plasmid DNA was linearized and serial diluted in order to create a standard curve to determine the PRRS viral load using the Promega (Madison, WI) buffers and XBA1 enzymes. RNA extraction was performed on serum in continuation for determining viral load using Trizol cell lysis reagent (5 Prime, Gaithersburg, MD) and Phase Lock Gels (Eppendorf AG; Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Analysis of Gene Expression

Total RNA was extracted from muscle and liver samples (100 mg) using Trizol cell lysis reagent (5 Prime) and Phase Lock Gels (Eppendorf AG; Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturers’ instructions as described previously (Rhoads et al., 2010). The RNA was cleaned with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA) and DNase treated with the RNase-Free DNase kit (Qiagen). The RNA content of each sample was calculated based on absorbance at 260 nm measured by spectrophotometry (Nanodrop 1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The RNA quality was evaluated by calculating the ratio of absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm, followed by Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.; Santa Clara, CA) analysis. The RNA was stored at −80 °C. The Bio-Rad iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Hercules, CA) for RT-qPCR was used to reverse transcribe 1 μg of RNA to cDNA.

Real-time quantitative PCR using SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix Kit from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) was performed on samples as described previously (Rhoads et al., 2011). Primers for each gene of interest were designed using the Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA; Table 2). PCR quantification of each sample was performed in triplicate and SYBER Green fluorescence was quantified with the CFX96 Touch Real Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). For each assay 40 PCR cycles were run and a dissociation curve was included to verify the amplification of a single PCR product. Analyses of amplification plots were performed with the CFX Manager Software version (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Data were analyzed using a five-point relative standard curve generated using serial 10-fold dilutions of cDNA prepared and pooled from experimental samples. Each assay plate contained negative controls and the standard curve to determine amplification efficiency of the respective primer pair. Unknown sample expression was then determined from the standard curve, and normalized to the geometric mean of the housekeeping genes (18S, EEFIA1, and β-actin).

Table 2.

Primers used for expression analyses

| Genes | Direction | Sequence 5′ to 3′ |

|---|---|---|

| PRRSV pACYC | Forward | GGCAACTCAGACGACCGAAC |

| Reverse | AGTAGTAATTGGACAGCGAGAAGG | |

| 18S rRNA | Forward | GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCAT |

| Reverse | CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG | |

| β-actin | Forward | CCAGCACCATGAAGATCAAGATC |

| Reverse | ACATCTGCTGGAAGGTGGACA | |

| EEFIA1 | Forward | TCATTGATGCTCCAGGACACA |

| Reverse | CCGTTCTTGGAAATACCTGCTT | |

| PDK2 | Forward | ACTGCAACGTCTCTGAGGTG |

| Reverse | AGGTGGGAGGGGACATAGAC | |

| PDK4 | Forward | CTGGGAGCACCACCCCACCT |

| Reverse | GCGCATCACAAAGCGAGCCG | |

| PC | Forward | CAGGAGAACATCCGCATCAAC |

| Reverse | ACCAGCAGGGAATCGTAGTG | |

| PEPCK1 | Forward | AGGAGAGAAAACGTAGGCGA |

| Reverse | GACTTTGGCCGAGTGGTTGA | |

| PEPCK2 | Forward | ACCAATGTGGCTGAGACGAG |

| Reverse | AGTTAGGATGTGCACAGGGC |

Fatty Acid Oxidation, Glucose Oxidation, and Metabolic Flexibility

Mitochondria were isolated from LD muscle as previously described with modifications (Frezza et al., 2007). Tissue samples were collected in buffer containing 67 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM EDTA/ Tris, and 10% bovine serum albumin (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Samples were minced and digested in 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min. Samples were homogenized and mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation.

Palmitate ([1-14C]-palmitic acid), glucose ([U-14C]-glucose), and pyruvate ([1-14C]-pyruvate) oxidation were performed as previously described (Hulver et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2014). Skeletal muscle samples used to assess substrate metabolism and metabolic flexibility were immediately placed in SET buffer (0.25 M Sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 0.01 M Tris-HCl and 2 mM ATP) and stored on ice until homogenization (~25 min). Each skeletal muscle sample was minced ~200 times with scissors, transferred to a glass homogenization tube and homogenized on ice using a Teflon pestle (12 passes at 150 RPM). The sample rested on ice for ~30 s and the homogenization steps were repeated. The homogenate was transferred to an Eppendorf tube and fresh sample was used to measure substrate oxidation and metabolic flexibility. Metabolic flexibility was assessed by comparing ([1-14C]-pyruvate) oxidation with and without 100 uM palmitic acid. The degree to which pyruvate oxidation decreased in the presence of FFA was used as an index of metabolic flexibility. A greater reduction (percent decrease) in pyruvate oxidation in the presence of palmitate is indicative of appropriate substrate switching and thus metabolic flexibility (Tarpey et al., 2017).

Reactive Oxygen Species

Amplex Red Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase assay Kit was used for measures of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production as performed previously (McMillan et al., 2015; Flack et al., 2016). To measure ROS production from complex 1, complex 3, and reverse electron transfer (REV), isolated mitochondria were plated on a 96-well black plate at a concentration of 5 ug/well under three different conditions, respectively. The three conditions were pyruvate (20 mM)/malate (10 mM)/oligomycin (2 µM)/rotenone (200 nM) for complex 1, pyruvate (20 mM)/malate (10 mM)/oligomycin (2 µM)/SOD (400 U/ml)/antimycin A (2 µM) for complex 3, and succinate (20 mM)/oligomycin (2 µM) for reverse electron flow to complex 1 (REV). Experiments were conducted in sucrose/mannitol solution in order to maintain the integrity of the mitochondria. Experiments consisted of 1 min delay and 1 min reading cycles, followed by a 5 s mixing cycle performed every third reading. All experiments were performed at 37 °C. Measures for ROS levels were conducted on a microplate reader (Biotek synergy 2, Winooski, VT). Fluorescence of Amplex Red, added prior to plate reading, was measured using a 530 nm excitation filter and a 560 nm emission filter.

Data Analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using the PROC MIXED procedure of SAS (Version 9.4, SAS institute Inc., Cary NC) with the experimental unit being pig. Data were evaluated using two distinct models. Daily measurements of rectal temperature, respiration rates, feed intake, and blood sample data were analyzed as a 2 × 2 factorial with repeated measures using an autoregressive covariance structure, with pig serving as the repeated unit and environment, PRRSV status, and day serving as the main effects. A Tukey adjustment was used to protect against type 1 error due to multiple comparisons. Least square means were separated with the PDIFF option. Data was tested for normality. For CBC and metabolic data, the model contained environment and PRRSV status as main effects and their interaction. Statistical differences were accepted as significant at P < 0.05 or a tendency at P < 0.10.

RESULTS

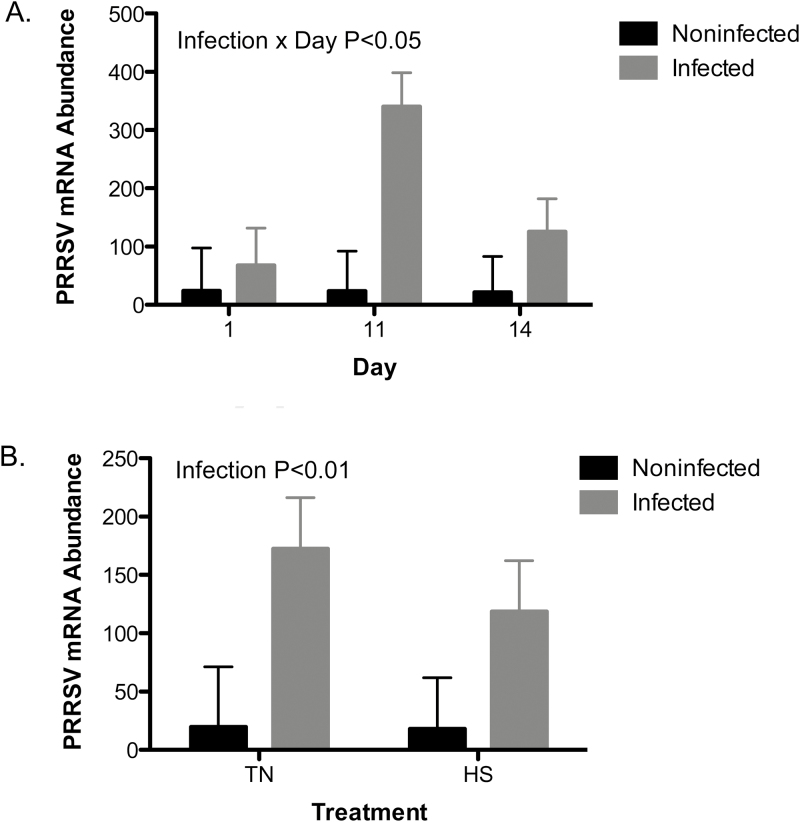

There were significant interactions between immune challenge and day for PRRSV mRNA abundance in pigs. Immune challenged pigs had an increased PRRS viral load (P < 0.05) on day 11 compared to day 1. In the noninfected group, there was no difference between days. We did not detect an effect of temperature on viral load (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Challenge of PRRSV and heat stress effects on temporal change in PRRS viremia. A PRRS viral challenge in thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions or uninfected thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions from day 1 to 11 and HS, uninfected (HS; 35 °C) conditions or HS infected (HP; 35 °C) conditions from day 11 to 14 on (A) temporal change of PRRS viral load and (B) effects of TN, TP, HS, and HP on change in viral load at day 14 of the experiment. Data represent LS means ± S.E.M. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

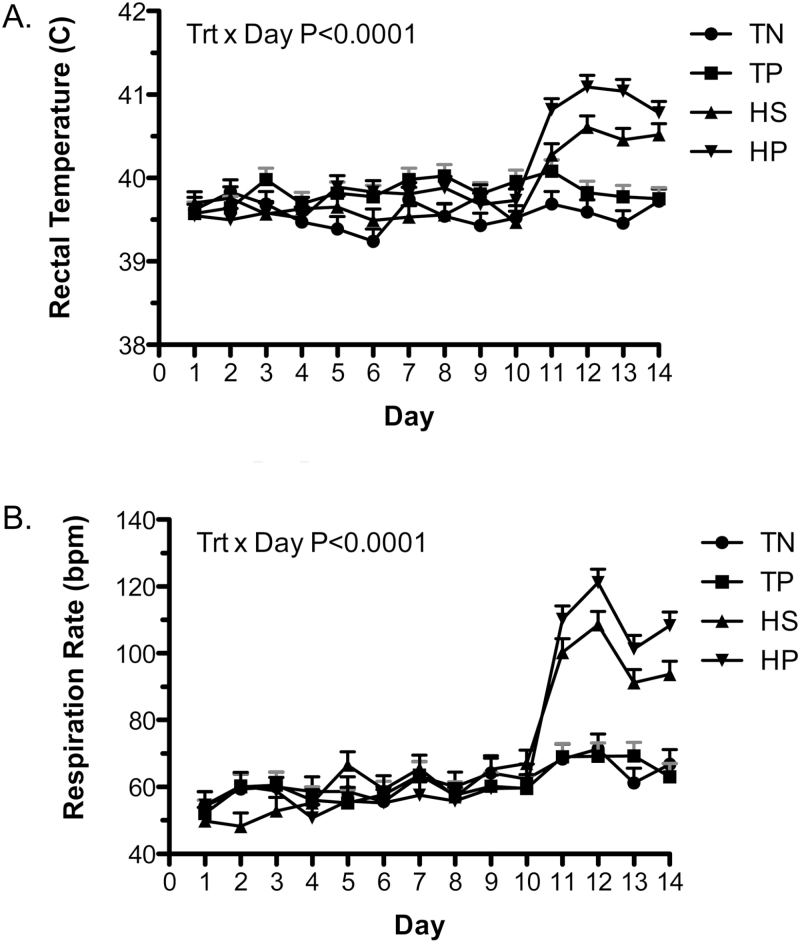

There was a treatment by day interaction for rectal temperature (P < 0.0001; Figure 2A). Pigs exposed to immune challenge, HS, or both had increased rectal temperatures compared to TN (P < 0.0001). Pigs with both immune and HS challenge (HP) had the highest rectal temperature. There was a treatment by day interaction (P < 0.0001) and a temperature effect (P < 0.0001) with increased respiration during HS compared to TN conditions (Figure 2B). Following initiation of HS, a tendency for increased (P < 0.1) respiration rate in HP animals compared to HS animals was observed during the last 3 d of the experiment. In comparison to the thermo-neutral environment pigs, the HS pigs exhibited increased (P < 0.0001) respiration rates (105 bpm vs. 67 bpm).

Figure 2.

Challenge effects of PRRS virus and HS on rectal temperature (A) and respiration rate (B). A PRRS viral challenge in thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions or uninfected thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions from day 1 to 11 and HS, uninfected (HS; 35 °C) conditions or HS infected (HP; 35 °C) conditions from day 11 to 14 on (A) Rectal temperature and (B) Respiration rates in growing pigs. Data represent LS means ± S.E.M. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

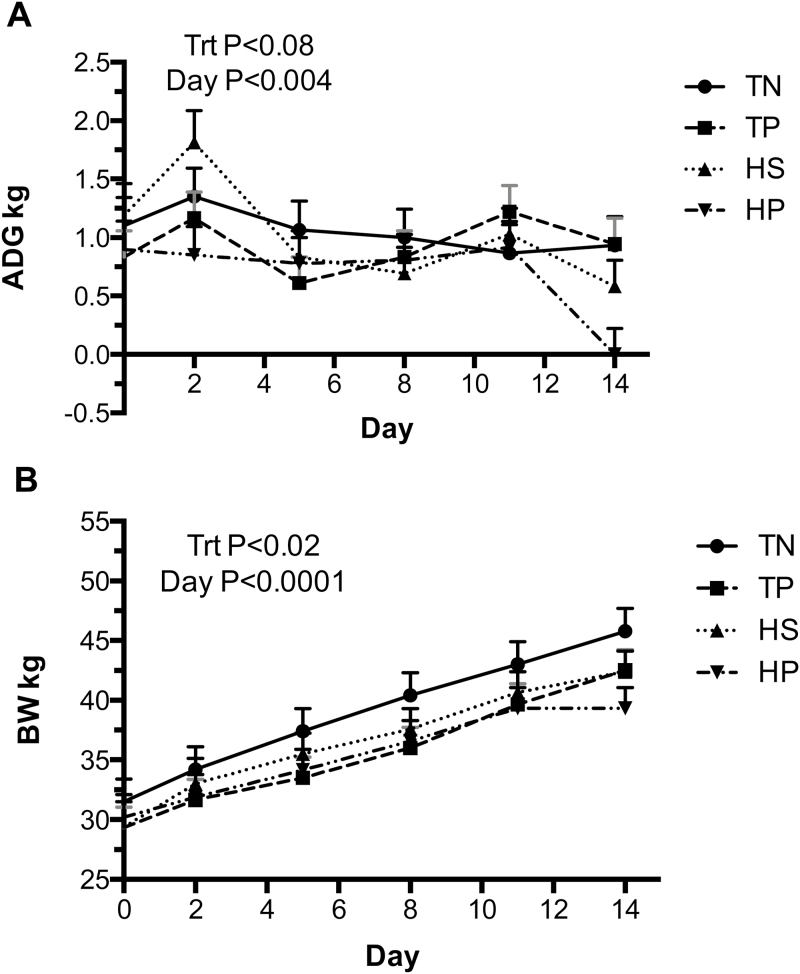

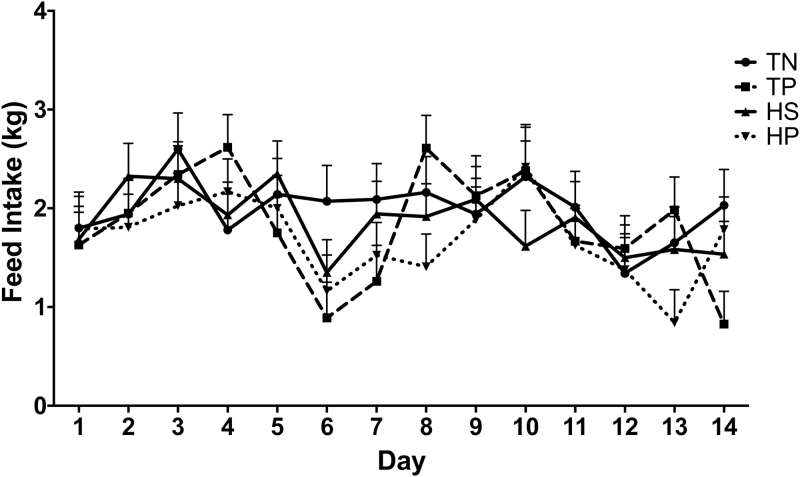

There was no treatment by day interactions for ADG and BW. Irrespective of day, immune challenge (TP) decreased ADG (P = 0.05) compared to TN, with the greatest decrease seen in the HP animals (Figure 3A). BW was less (P < 0.05) in TP, HS, and HP pigs as compared to TN animals (35.4 kg, 36.4 kg, 35.2 kg vs. 38.7 kg; Figure 3B). On day 14, BW was decreased in HP pigs compared to TN pigs (39.3 kg vs. 45.8 kg) (P < 0.05). Noninfected animals had a tendency to have greater feed intake (P = 0.06) than PRRSV infected animals with an intake of 1.93 and 1.77 kg/d, respectively (Figure 4). Feed intake did not differ between environments (P = 0.12; Figure 4). There was no interaction between environment and infection on feed intake (P = 0.99).

Figure 3.

Challenge effects of PRRS virus and HS on ADG (A) and BW (B). A PRRS viral challenge in thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions or uninfected thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions from day 1 to 11 and HS, uninfected (HS; 35 °C) conditions or HS infected (HP; 35 °C) conditions from day 11 to 14. Data represent LS means ± S.E.M. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Challenge effects of PRRS virus and HS on average daily feed intake. A PRRS viral challenge in thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions or uninfected thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions from day 1 to 11 and HS, uninfected (HS; 35 °C) conditions or HS infected (HP; 35 °C) conditions from day 11 to 14. Data represent LS means ± S.E.M. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Blood metabolite analyses indicated an effect on protein metabolism by both TP and HS. There was a treatment by day interaction for CK level (P < 0.05) (Table 3). On day 14, HS pigs had the highest CK level; TP and HP pigs had intermediate CK compared to TN and HS pigs. Creatinine levels increased for HP pigs compared to HS and TP pigs (P < 0.01, Table 3). Creatinine in HP pigs increased (P < 0.01, Table 3) on day 14 compared to day 11 and was elevated (P < 0.05, Table 3) on day 14 compared to TP pigs. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were different by day (P < 0.05, Table 3) where BUN increased on day 11 and 14 compared to day 1, but there were no treatment effects detected.

Table 3.

Effects of PRRS virus and HS on plasma metabolite concentration in growing pigs

| Days of experimenta | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 14 | P-value | |||||||||||||

| Variable | TNb | HS | TPc | HPd | TN | HS | TP | HP | TN | HS | TP | HP | SEM | Trt | Day | T × D2 |

| CK, ULe | 4,680 | 1,710 | 2,979 | 2,015 | 8,349 | 2,456 | 3,326 | 1,417 | 2,618 | 15,119 | 3,818 | 4,699 | 2,101 | 0.16 | 0.05 | <0.005 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 1.0 | 0.92 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.98 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.05 | <0.02 | <.0001 | <0.01 |

| Urea Nitrogen, mg/dL | 10.8 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 11.5 | 14.2 | 12.0 | 13.3 | 11.3 | 13.6 | 14.0 | 12.5 | 12.6 | 1.0 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.58 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 120.8 | 122.3 | 127.7 | 119.0 | 117.2 | 108.7 | 112.5 | 109.2 | 134.6 | 114.2 | 125.8 | 112.7 | 5.1 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.45 |

aPigs were exposed to thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions; thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions; HS (35 °C) conditions; or HS infected (HP; 35 °C). A PRRS viral challenge in thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions or uninfected thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions from day 1 to 11 and HS, uninfected (HS; 35 °C) conditions or HS infected (HP; 35 °C) conditions from day 11 to 14 Significant difference at P < 0.05. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6.

bThermo-neutral.

cThermo-neutral and PRRSV.

dHS and PRRSV.

eCreatine Kinase.

Plasma glucose concentration tended to differ between treatments (P < 0.06) as concentration decreased during HS (Table 3). Plasma glucose concentrations decreased (P < 0.05) between day 1 and 11 and increased (P < 0.05) between day 11 and 14.

Analysis of CBC data are shown in Table 4. White blood cell (WBC) counts had a tendency to decrease (P = 0.1) with HS compared to TN. The percentage of lymphocytes also decreased (P < 0.01) during HS compared to TN animals. However, increased monocyte (P < 0.05) and eosinophil (P < 0.05) percent was observed during HS compared to TN. Percent segmented neutrophils tended to increase (P < 0.1) during HP compared to HS and TP. No significant difference in red blood cells and platelets was observed.

Table 4.

Effects of PRRS virus and HS on CBC in growing pigs

| Day 14 of experiment a | P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | TNb | HS | TPc | HPd | SEM | Temp | Immune | T × I |

| RBCe | 7.66 | 7.36 | 7.35 | 7.10 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.92 |

| WBCf | 23.0 | 19.7 | 25.0 | 20.4 | 2.9 | 0.10 | 0.56 | 0.78 |

| Lymph%g | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.002 | 0.58 | 0.17 |

| SEG%h | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.48 | <0.1 |

| MONO%i | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.33 |

| EOS%j | 0.012 | 0.025 | 0.005 | 0.040 | 0.011 | <0.02 | 0.65 | 0.22 |

| Platelets | 397.4 | 324.0 | 446.8 | 276.5 | 151.8 | 0.32 | 0.99 | 0.69 |

aPigs were exposed to thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions; thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions; HS (35 °C) conditions; or HS infected (HP; 35 °C). Significant difference at P < 0.05. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6.

bThermo-neutral.

cThermo-neutral and PRRSV.

dHS and PRRSV.

eRed blood cells.

fWhite blood cells.

gLymphocytes percent of WBC.

hSegmented neutrophils percent of WBC.

iMonocytes percent of WBC.

jEosinophils percent of WBC.

Metabolic flexibility measured by percent change in pyruvate oxidation in response to FFA, tended to decrease (P = 0.08) in PRRS infected pigs (3.98 vs. 19.09) compared to noninfected (Table 5). Metabolic flexibility tended to decrease during HS. Fatty Acid oxidation via CO2 production decreased (P < 0.05, Table 5) in combination challenged pigs compared to PRRSV and HS challenge (0.108 vs. 0.157, 0.161 nmol/mg protein/h) respectively. No significant differences were observed in pyruvate oxidation, pyruvate +FA oxidation, incomplete fatty acid oxidation (acid soluble metabolites), and total fatty acid oxidation (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effects of PRRS virus and HS on skeletal muscle metabolic flexibility in growing pigs

| Environmenta | P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variableb | TNc | HS | TPd | HPe | SEM | Temp | Immune | T × I |

| Pyruvate Oxidation | 324.53 | 366.02 | 359.82 | 344.53 | 47.39 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.57 |

| Pyruvate + FA Oxidation | 249.64 | 312.33 | 325.92 | 306.26 | 33.94 | 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| Metabolic Flexibility% | 22.87 | 15.31 | 3.43 | 4.52 | 7.92 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.59 |

| FAO Oxidationf | 0.086 | 0.161 | 0.157 | 0.108 | 0.027 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.04 |

| FAO ASMg | 2.23 | 2.25 | 2.18 | 1.47 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.19 |

| FAO Totalh | 2.31 | 2.41 | 2.34 | 1.58 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

aPigs were exposed to thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions; thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions; HS (35 °C) conditions; or HS infected (HP; 35 °C). Significant difference at P < 0.05. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6.

bThe units for pyruvate oxidation, pyruvate+FA oxidation, FAO oxidation, FAO ASM, FAO total is nmol/mg protein/h.

cThermo-neutral.

dThermo-neutral and PRRSV.

eHS and PRRSV.

fFatty acid oxidation by CO2 production.

gFatty acid oxidation by Acid soluble metabolites.

hTotal fatty acid oxidation.

Skeletal muscle PDK2 mRNA abundance was down regulated (P < 0.05) in HS compared to TN conditions, but not affected by immune status (Table 6). There was an interaction between temperature and immune status in skeletal muscle PDK4 gene abundance (P < 0.05). HS increased PDK4 mRNA expression compared to TN, and PRRS challenge increased PDK4 mRNA expression under TN conditions compared to HS conditions. No significant differences were observed in metabolic gene expression in the liver of PC, PEPCK1, and PEPCK2 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effects of PRRS virus and HS on metabolic gene abundance

| Environmenta | P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | TNb | HS | TPc | HPd | SEM | Temp | Immune | T × I |

| PC (liver)e | 0.0011 | 0.0030 | 0.0012 | 0.0013 | 0.0008 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.25 |

| PEPCK1 (liver)f | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.19 |

| PEPCK2 (liver) | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 0.23 |

| PDK2 (muscle)g | 0.00037 | 0.00024 | 0.00044 | 0.00021 | 0.00004 | 0.001 | 0.66 | 0.26 |

| PDK4 (muscle) | 0.00023 | 0.00049 | 0.00124 | 0.00025 | 0.00023 | 0.17 | 0.15 | <0.03 |

aPigs were exposed to thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions; thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions; HS (35 °C) conditions; or HS infected (HP; 35 °C). Significant difference at P < 0.05. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6.

bThermo-neutral.

cThermo-neutral and PRRSV.

dHS and PRRSV.

ePyruvate carboxylase.

fPhosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase.

gPyruvate dehydrogenase kinase.

We observed no differences in production of mitochondrial ROS from REV and electron transport chain complexes I and III, compared to controls (Table 7).

Table 7.

Effects of PRRS virus and HS on skeletal muscle mitochondrial ROS production in growing pigs

| Environmenta | P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (FU/min*µg) | TNb | HS | TPc | HPd | SEM | Temp | Immune | T × I |

| ROS Complex 1e | 104.4 | 95.8 | 76.2 | 88.5 | 14.1 | 0.90 | 0.23 | 0.48 |

| ROS Complex 3f | 171.6 | 177.0 | 158.3 | 153.2 | 25.5 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.84 |

| ROS REVg | 693.6 | 777.67 | 766.8 | 746.2 | 116.0 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.66 |

aPigs were exposed to thermo-neutral (TN; 22 °C) conditions; thermo-neutral infected (TP; 22 °C) conditions; HS (35 °C) conditions; or HS infected (HP; 35 °C). SEM HP: 15.4; 28.0; 127.1. Significant difference at P < 0.05. TN n = 5, TP n = 6, HS n = 6, HP n = 6.

bThermo-neutral.

cThermo-neutral and PRRSV.

dHS and PRRSV.

eMitochondrial ROS Complex 1.

fMitochondrial ROS Complex 3.

gMitochondrial ROS REV receptor.

DISCUSSION

Pathogenic and HS challenges antagonize growing pig performance and economic gain. Determining the mechanism(s) by which these changes independently or interactively impact whole-body or tissue energy homeostasis and metabolism in growing pigs may allow for future nutritional or pharmaceutical interventions to ameliorate the negative effects of challenge.

PRRS viremia was significantly increased in the challenged pigs, and as expected, the viral load varied by day, displaying a dramatic increase from day 1 to day 11 post infection, and then decreased from day 11 to 14 as the pigs recovered. An initial effect of each challenge, depending on severity, is increased body temperature (Sutherland et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2012; Pearce et al., 2013a; 2013b; Kim et al., 2015). In this study, the experimental protocol resulted in marked pyrexia as all infected animals had increased body temperatures 3 d after inoculation compared to TN, and this was sustained throughout the experimental period. Hyperthermia ensued after initiation of HS as all body temperatures were elevated above that of TN. The HS regimen was held constant at 35 °C ± 1 °C and lacked a cyclical or diurnal pattern of ambient temperature, which prevented the pigs from returning to euthermia during the cooler hours of the night. Consequently, our HS protocol may resemble tropical or semitropical regions and southern regions of the United States. According to USDA (APHIS, 2009) the percentage of unvaccinated pigs that were positive for PRRS virus in the southern region of United States is 69.6%, which was higher than that of north, west central and east central area (59.3%, 41.7%, and 30.2% respectively). Therefore, the interactive effects of these two stresses on pig performance is economically important.

HS conditions caused a dramatic increase in respiration rate compared to TN, although infection did not play a significant role. The lack of functional sweat glands in pigs does not permit normal skin evaporative cooling (Anderson and Bates, 1984). As the pigs heat load increases the pigs increase respiration rate to dissipate heat (Patience et al., 2005).

A conserved response to challenged animals is reduced feed intake (Neumann et al., 2005; Renaudeau et al., 2012). In our study, feed intake decreased during PRRSV challenge although it did not significantly differ in response to HS. The lack of a significant decrease in feed intake due to HS differs from our previous study (Pearce et al., 2013a). A possible explanation may be due to differences in magnitude of HS between the two studies where Pearce et al., observed a greater rectal temperature and respiration rate (approximately 1 °C and 20 bpm greater, respectively) than the current study. The reduced feed intake during PRRSV infection may be responsible for the negative impact on growth observed in the HP pigs. However, it has been demonstrated previously that decreased ADG was not solely due to decreased feed intake, as pair-fed counterparts had a greater reduced ADG compared to HS animals (Pearce et al., 2013a). Significant reductions in feed intake and ADG were also reported previously in PRRSV infected pigs (Escobar et al., 2006; Sutherland et al., 2007; Li et al., 2015; Schweer et al., 2016). On day 5 post challenge, ADG was reduced in HP pigs and by day 11 had recovered to pre-infection status. However, addition of HS to the PRRSV infection resulted in a dramatic decline in ADG of the HP challenge that was greater than either TP or HS challenge. The physical parameters measured in this study indicate combination challenged pigs had the most detrimental impacts on production than either PRRSV or HS alone consistent with the notion that multiple stressors can negatively impact growth or other parameters in an additive fashion as demonstrated previously (Laugero and Moberg, 2000; Carroll et al., 2012).

CBCs in heat stressed chickens show decreased WBC counts and antibody production (Mashaly et al., 2004). In heat stressed pigs, increased neutrophil numbers were seen whereas antibody-producing cells decreased (Morrow-Tesch et al., 1994). In support of this, we observed decreased lymphocytes and a trend toward decreased WBC counts during HS as well as increased monocytes and eosinophils. Also, neutrophil numbers were elevated during the combined challenges in comparison to individual challenges. It is tempting to speculate that HS requires more of an innate immune response verse an adaptive response. In a similar study to the current study, Sutherland et al. (2007) examined the impact of heat and PRRSV infection on pig physiology. Although a significant infection by temperature interaction was not observed for the immune measures, PRRSV infection did alter immune cell populations by decreasing lymphocyte percentage and increasing total number of macrophages. It also has been reported that infection with a highly pathogenic PRRSV strain showed elevated levels of macrophages and neutrophils in the lung (Han et al., 2014). However, we failed to find an effect of PRRSV infection on immune cells in the blood. An obvious explanation may relate to infection length and severity. Pigs were infected on day 1, and the blood counts were only measured on day 14. It is possible that immune cell counts were changed on the first a few days of infection and back to normal 2 wk later consistent with previous observations demonstrating transient leukopenia and lymphopenia (Nielsen and Bøtner, 1997; Toepfer-Berg et al., 2004; Sutherland et al., 2007).

Muscle growth is dependent on the occurrence of greater protein accretion than protein degradation. Muscle accounts for 60–75% of BW which makes it a good source of amino acids and energy (Frost and Lang, 2007). Negative energy balance may cause skeletal muscle degradation and increased circulating urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine, which can be used to assess proteolysis (Pearce et al., 2013a; 2013b). In this study, BUN was not affected by treatment, but was increased on day 11 and day 14 compared to day 1. Increased BUN has been observed during HS in pigs, cows, and heifers (Rhoads et al., 2013). Pearce et al. (2013a; 2013b) observed a decline in BUN levels after 3 d of HS. This suggests that BUN in HS pigs may have been elevated at initial onset of treatment and declined over time. In LPS infected pigs, BUN was observed to increase 8 to 12 h after infection, and only tended toward elevation by 24 h (Webel et al., 1997). Consistent with those results, Stuart et al. (2015) found that BUN was not affected by either LPS or PRRSV after 48 h of challenge in growing pigs. It is possible that BUN is a short-term measure of proteolysis and blood sampling was not frequent enough to observe a change. In our experiment, plasma creatinine was elevated in HS, immune, and multiple challenged pigs compared to thermo-neutral controls. Creatinine can be an indicator of muscle proteolysis as it is produced from the breakdown of creatine phosphate. Creatine phosphate is converted to creatine by CK during muscle catabolism (Berg, 2007). Increased plasma creatinine results agree with previous data in heat stressed swine (Pearce et al., 2013a). Plasma CK levels were elevated on day 14, suggesting that an increase in muscle catabolism was occurring over the challenged pigs. The increased creatinine and CK levels during HS and immune challenge support the notion of increased muscle degradation.

Skeletal muscle plays an important role in regulating whole body energy homeostasis and is a major site for glucose and fatty acid oxidation. Fatty acid oxidation measured by CO2 production (complete fatty acid oxidation) significantly decreased during HS and PRRS challenge compared to PRRS challenge only. Fatty acid oxidation measured by ASM (incomplete fatty acid oxidation) numerically decreased during the combination challenge as well as total fatty acid oxidation. This observation may indicate that during a combination challenge there was decreased fatty acid use. Additionally, plasma glucose tended to decrease in heat stressed and combination challenged animals, possibly indicating a shift between fuel sources of fatty acids and glucose or reduced feed intake. Therefore, metabolic flexibility, the ability to switch between carbohydrates and lipids as fuel sources (Stump et al., 2006) was measured by the degree to which pyruvate oxidation decreased in the presence of FFA. The PRRSV challenged pigs appeared to become less metabolically flexible compared to noninfected pigs. In addition, when evaluated solely on temperature, HS pigs appeared to become less metabolically flexible compared to TN pigs. A decrease in metabolic flexibility in PRRS infected and HS pigs suggests the muscle may lose the ability to switch from glucose to fatty acid oxidation. This may be part of the reason for altered body composition and adipose retention that has been observed during HS (Verstegen et al., 1978; Heath, 1983; Baumgard and Rhoads, 2013).

Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH) catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, the latter being a common intermediate in glucose and fatty acid metabolism making PDH a target for substrate competition between those two fuels (Sugden et al., 2001). Phosphorylation of PDH by PDK causes inactivation and a shift toward fatty acid oxidation to spare glucose (Sugden and Holness, 2003). Among four PDK isoenzymes, PDK2 is extensively expressed in all the tissues, and PDK4 is highly expressed in heart and skeletal muscle (Bowker-Kinley et al., 1998). In this study, we observed increased PDK4 mRNA expression during HS. An elevated PDK4 expression has also been observed during HS by Sanders et al. (2009). However, PDK2 expression was decreased in HS animals. Since contrary results were obtained, the phosphorylation level needs to be measured in the future to elucidate the effect of HS on PDH. We also observed an increase in PDK4 mRNA expression in PRRS infected pigs under TN condition. In agreement with our result, influenza A virus infection has been observed to suppress mitochondrial energy homeostasis by up-regulating PDK4 in mouse muscle (Yamane et al., 2014). Increased PDK4 expression acts to inactivate PDH and reduce substrate oxidation, which may serve to reduce mitochondrial ROS production and prevent cellular damage (Baumgard and Rhoads, 2012).

ROS can be produced by oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria. Under normal physiological conditions, ROS production is regulated by complex 1 and electron scavengers. However, when mitochondria are malfunctioning there are excessive amounts of electrons that accumulate in the electron carriers that increase ROS production (Wallace and Fan, 2010). The mitochondrial oxidative capacity is typically reduced and ROS production elevated during reduced metabolic flexibility (Stump et al., 2006). Interestingly, analysis of mitochondrial ROS produced by complex 1, complex 3, and REV was not significantly affected by any challenge condition.

In conclusion, a combination challenge appears to have the most detrimental impacts on physiological parameters with respect to body temperature and BW gain in pigs. The combination challenged animals also displayed the highest degree of muscle degradation as indicated by the blood markers creatinine, CK, and BUN. During HS, decreased blood glucose concentration and decreased metabolic flexibility were observed. In the combination challenged pigs, decreased fatty acid oxidation and metabolic flexibility was also observed. Collectively, these data may indicate that the combination of HS and PRRSV reduces growth performance in growing pigs due to significant metabolic changes including protein degradation and reduced metabolic flexibility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Projects and results described herein were supported by National Research Initiative Competitive (2008-35206-18817) and Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive (2010-65206-20644, 2011-6700330007 and 2014-67015-21627) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

LITERATURE CITED

- Anderson J. F., and Bates D. W.. 1984. Environmental-management in animal agriculture - Curtis,SE. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 184:592. [Google Scholar]

- APHIS 2009. PRRS Seroprevalence on U.S. Swine Operations Veterinary Services Centers for Epidemiology and Animal Health. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgard L. H., and Rhoads R. P.. 2012. Ruminant nutrition symposium: ruminant production and metabolic responses to heat stress. J. Anim. Sci. 90:1855–1865. doi:10.2527/jas.2011-4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgard L. H., and Rhoads R. P. Jr. 2013. Effects of heat stress on postabsorptive metabolism and energetics. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 1:311–337. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-031412-103644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J. M., Tymoczko J. L., and Stryer L.. 2007. Biochemistry. 5th ed New York: W H Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bowker-Kinley M. M., Davis W. I., Wu P., Harris R. A., and Popov K. M.. 1998. Evidence for existence of tissue-specific regulation of the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem. J. 329:191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J. A., Burdick N. C., Chase C. C. Jr, Coleman S. W., and Spiers D. E.. 2012. Influence of environmental temperature on the physiological, endocrine, and immune responses in livestock exposed to a provocative immune challenge. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 43:146–153. doi:10.1016/j.domaniend.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, J., T. L. Toepfer-Berg, J. Chen, W. G. Van Alstine, J. M. Campbell, and R. W. Johnson RW. 2006. Supplementing drinking water with Solutein did not mitigate acute morbidity effects of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 84:2101–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack K. D., Davy B. M., DeBerardinis M., Boutagy N. E., McMillan R. P., Hulver M. W., Frisard M. I., Anderson A. S., Savla J., and Davy K. P.. 2016. Resistance exercise training and in vitro skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in older adults. Physiol. Rep. 4:e12849. doi:10.14814/phy2.12849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezza C., Cipolat S., and Scorrano L.. 2007. Organelle isolation: functional mitochondria from mouse liver, muscle and cultured fibroblasts. Nat. Protoc. 2:287–295. doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R. A., and Lang C. H.. 2007. Regulation of muscle growth by pathogen associated molecules. Poultry Sci. 86:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D., Hu Y., Li L., Tian H., Chen Z., Wang L., Ma H., Yang H., and Teng K.. 2014. Highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection results in acute lung injury of the infected pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 169:135–146. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath M. E. 1983. The effects of rearing-temperature on body composition in young pigs. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. a. Comp. Physiol. 76:363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann J. R., Muñoz-Zanzi C. A., Roof M. B., Burkhart K., and Zimmerman J. J.. 2005. Probability of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus infection as a function of exposure route and dose. Vet. Microbiol. 110:7–16. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulver M. W., Berggren J. R., Carper M. J., Miyazaki M., Ntambi J. M., Hoffman E. P., Thyfault J. P., Stevens R., Dohm G. L., Houmard J. A.,. et al. 2005. Elevated stearoyl-coa desaturase-1 expression in skeletal muscle contributes to abnormal fatty acid partitioning in obese humans. Cell Metab. 2:251–261. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachauri, R. K., M. R. Allen, V. R. Barros, J. Broome, W. Cramer, R. Christ, J. A. Church, L. Clarke, Q. Dahe, P. Dasgupta. 2014. In: Pachauri, R., and L. Meyer, editors. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC; p. 151, ISBN: 978-92-9169-143-2. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. W. 1997. Inhibition of growth by pro-inflammatory cytokines: an integrated view. J. Anim. Sci. 75:1244–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T., C. Park, K. Choi, J. Jeong, I. Kang, S. J. Park, and C. Chae. 2015. Comparison of two commercial type 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) modified live vaccines against heterologous type 1 and type 2 PRRSV challenge in growing pigs. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 22:631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugero K. D., and Moberg G. P.. 2000. Summation of behavioral and immunological stress: metabolic consequences to the growing mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 279:E44–E49. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.1.E44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. M., Seelenbinder K. M., Ponder M. A., Deng L., Rhoads R. P., Pelzer K. D., Radcliffe J. S., Maxwell C. V., Ogejo J. A., and Hanigan M. D.. 2015. Effects of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on pig growth, diet utilization efficiency, and gas release from stored manure. J. Anim. Sci. 93:4424–4435. doi:10.2527/jas.2015-8872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashaly M. M., Hendricks G. L. III, Kalama M. A., Gehad A. E., Abbas A. O., and Patterson P. H.. 2004. Effect of heat stress on production parameters and immune responses of commercial laying hens. Poult. Sci. 83:889–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan R. P., Wu Y., Voelker K., Fundaro G., Kavanaugh J., Stevens J. R., Shabrokh E., Ali M., Harvey M., Anderson A. S.,. et al. 2015. Selective overexpression of toll-like receptor-4 in skeletal muscle impairs metabolic adaptation to high-fat feeding. Am. j. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 309:R304–R313. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00139.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Tesch, J. L., J. J. Mcglone, and J. L. Salak-Johnson. 1994. Heat and social stress effects on pig immune measures. J. Anim. Sci. 72:2599–2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann E. J., Kliebenstein J. B., Johnson C. D., Mabry J. W., Bush E. J., Seitzinger A. H., Green A. L., and Zimmerman J. J.. 2005. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome on swine production in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 227:385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J., and Bøtner A.. 1997. Hematological and immunological parameters of 4 ½-month old pigs infected with PRRS virus. Vet. Microbiol. 55:289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patience J. F., Umboh J. F., Chaplin R. K., and Nyachoti C. M.. 2005. Nutritional and physiological responses of growing pigs exposed to a diurnal pattern of heat stress. Livest. Prod. Sci. 96:205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce S. C., Gabler N. K., Ross J. W., Escobar J., Patience J. F., Rhoads R. P., and Baumgard L. H.. 2013a. The effects of heat stress and plane of nutrition on metabolism in growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 91:2108–2118. doi:10.2527/jas.2012-5738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce S. C., Mani V., Boddicker R. L., Johnson J. S., Weber T. E., Ross J. W., Rhoads R. P., Baumgard L. H., and Gabler N. K.. 2013b. Heat stress reduces intestinal barrier integrity and favors intestinal glucose transport in growing pigs. Plos One 8:e70215. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeyro P. E., Kenney S. P., Giménez-Lirola L. G., Heffron C. L., Matzinger S. R., Opriessnig T., and Meng X. J.. 2015. Expression of antigenic epitopes of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in a modified live-attenuated porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) vaccine virus (PCV1-2a) as a potential bivalent vaccine against both PCV2 and PRRSV. Virus Res. 210:154–164. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaudeau D., Collin A., Yahav S., de Basilio V., Gourdine J. L., and Collier R. J.. 2012. Adaptation to hot climate and strategies to alleviate heat stress in livestock production. Animal 6:707–728. doi:10.1017/S1751731111002448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads R. P., Baumgard L. H., and Suagee J. K.. 2013. 2011 and 2012 early careers achievement awards: metabolic priorities during heat stress with an emphasis on skeletal muscle. J. Anim. Sci. 91:2492–2503. doi:10.2527/jas.2012-6120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads M. L., Kim J. W., Collier R. J., Crooker B. A., Boisclair Y. R., Baumgard L. H., and Rhoads R. P.. 2010. Effects of heat stress and nutrition on lactating holstein cows: II. Aspects of hepatic growth hormone responsiveness. J. Dairy Sci. 93:170–179. doi:10.3168/jds.2009-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads R. P., La Noce A. J., Wheelock J. B., and Baumgard L. H.. 2011. Alterations in expression of gluconeogenic genes during heat stress and exogenous bovine somatotropin administration. J. Dairy Sci. 94:1917–1921. doi:10.3168/jds.2010-3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads M. L., Rhoads R. P., VanBaale M. J., Collier R. J., Sanders S. R., Weber W. J., Crooker B. A., and Baumgard L. H.. 2009. Effects of heat stress and plane of nutrition on lactating holstein cows: I. Production, metabolism, and aspects of circulating somatotropin. J. Dairy Sci. 92:1986–1997. doi:10.3168/jds.2008-1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S. R., Cole L. C., Flann K. L., Baumgard L. H., and Rhoads R. P.. 2009. Effects of acute heat stress on skeletal muscle gene expression associated with energy metabolism in rats. Faseb J. 23:598.7. (Abstr.). [Google Scholar]

- Schweer, W. P., S. C. Pearce, E. R. Burrough, K. Schwartz, K. J. Yoon, J. C. Sparks, and N. K. Gabler. 2016. The effect of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus challenge on growing pigs II: intestinal integrity and function. J. Anim. Sci. 94:523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, W. D., T. E. Burkey, N. K. Gabler, K. Schartz, and C. F. M. De Lange. 2015. Models of immune system stimulation in growing pigs: porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) versus E. coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS). J. Anim. Sci. 93(E-Suppl 2):165. (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- Stump C. S., Henriksen E. J., Wei Y., and Sowers J. R.. 2006. The metabolic syndrome: role of skeletal muscle metabolism. Ann. Med. 38:389–402. doi:10.1080/07853890600888413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden M. C., Bulmer K., and Holness M. J.. 2001. Fuel-sensing mechanisms integrating lipid and carbohydrate utilization. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 29:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden M. C., and Holness M. J.. 2003. Recent advances in mechanisms regulating glucose oxidation at the level of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by PDKs. Am. j. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 284:E855–E862. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00526.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland M. A., Niekamp S. R., Johnson R. W., Van Alstine W. G., and Salak-Johnson J. L.. 2007. Heat and social rank impact behavior and physiology of PRRS-virus-infected pigs. Physiol. Behav. 90:73–81. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpey M. D., Davy K. P., McMillan R. P., Bowser S. M., Halliday T. M., Boutagy N. E., Davy B. M., Frisard M. I., and Hulver M. W.. 2017. Skeletal muscle autophagy and mitophagy in endurance-trained runners before and after a high-fat meal. Mol. Metab. 6:1597–1609. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toepfer-Berg T. L., Escobar J., Van Alstine W. G., Baker D. H., Salak-Johnson J., and Johnson R. W.. 2004. Vitamin E supplementation does not mitigate the acute morbidity effects of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 82:1942–1951. doi:10.2527/2004.8271942x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstegen M. W. A., Brascamp E. W., and Vanderhel W.. 1978. Growing and fattening of pigs in relation to temperature of housing and feeding level. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 58:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D. C., and Fan W.. 2010. Energetics, epigenetics, mitochondrial genetics. Mitochondrion 10:12–31. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel D. M., Finck B. N., Baker D. H., and Johnson R. W.. 1997. Time course of increased plasma cytokines, cortisol, and urea nitrogen in pigs following intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide. J. Anim. Sci. 75:1514–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane K., Indalao I. L., Chida J., Yamamoto Y., Hanawa M., and Kido H.. 2014. Diisopropylamine dichloroacetate, a novel pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 inhibitor, as a potential therapeutic agent for metabolic disorders and multiorgan failure in severe influenza. Plos One 9:e98032. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., McMillan R. P., Hulver M. W., Siegel P. B., Sumners L. H., Zhang W., Cline M. A., and Gilbert E. R.. 2014. Chickens from lines selected for high and low body weight show differences in fatty acid oxidation efficiency and metabolic flexibility in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 38:1374–1382. doi:10.1038/ijo.2014.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]