Abstract

Rapeseed (RS) is an abundant and inexpensive source of energy and AA in diets for monogastrics and a sustainable alternative to soybean meal. It also contains diverse bioactive phytochemicals that could have antinutritional effects at high dose. When the RS-derived feed ingredients (RSF) are used in swine diets, the uptake of these nutrients and phytochemicals is expected to affect the metabolic system. In this study, 2 groups of young pigs (17.8 ± 2.7 kg initial BW) were equally fed a soybean meal-based control diet and an RSF-based diet, respectively, for 3 wk. Digesta, liver, and serum samples from these pigs were examined by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry–based metabolomic analysis to determine the metabolic effects of the 2 diets. Analyses of digesta samples revealed that sinapine, sinapic acid, and gluconapin were robust exposure markers of RS. The distribution of free AA along the intestine of RSF pigs was consistent with the reduced apparent ileal digestibility of AA observed in these pigs. Despite its higher fiber content, the RSF diet did not affect microbial metabolites in the digesta, including short-chain fatty acids and secondary bile acids. Analyses of the liver and serum samples revealed that RSF altered the levels of AA metabolites involved in the urea cycle and 1-carbon metabolism. More importantly, RSF increased the levels of multiple oxidized metabolites and aldehydes while decreased the levels of ascorbic acid and docosahexaenoic acid–containing lipids in the liver and serum, suggesting that RSF could disrupt redox balance in young pigs. Overall, the results indicated that RSF elicited diverse metabolic events in young pigs through its influences on nutrient and antioxidant metabolism, which might affect the performance and health in long-term feeding and also provide the venues for nutritional and processing interventions to improve the utilization of RSF in pigs.

Keywords: amino acid metabolism, metabolomics, rapeseed, redox balance, swine

INTRODUCTION

Rapeseed (RS; Brassica sp.) has an AA profile and energy content comparable to soybean (Rutkowski, 1971). Rapeseed-derived feed ingredients (RSF), such as RS meal (RSM), are considered an economical source of AA and energy for monogastrics. However, widespread adoption of RSF is limited because RS components, mainly fiber and phytochemicals, have negative impacts on animal growth performance and health. For example, high-fiber content in RSF may interfere with digestibility of other nutrients (Noblet et al., 2013). More importantly, bioactive phytochemicals in RSF, including glucosinolates, phenolic acids, and erucic acid, function as antinutrients at high doses (Mailer et al., 2008). Glucosinolates are thioglucose compounds that have goitrogenic and hepatotoxic effects at high doses (Mawson et al., 1994a; Tripathi and Mishra, 2007), while phenolic acids may decrease palatability of the diet by contributing to a bitter taste and astringency of RSF. Overall, the influence of RSF on animal growth performance is largely determined by the balance between the nutritional and antinutritional events elicited by RS components.

Feed efficiency is of great interest for pig and poultry production because feed represents over 70% of the total production cost. Feed efficiency is the result of digestion, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of nutrients in feed. These processes are responsible for linking the diet and growth performance responses and have been reported as major contributors to variation in feed efficiency (Herd and Arthur, 2009). Because RS contains abundant nutrients and diverse bioactive phytochemicals, the disposition of RSF is expected to result in unique changes and features in the body through both direct contribution and indirect regulation, especially in the metabolome. However, knowledge on the metabolic effects of RSF is primarily limited to growth performance, energy and nutrient digestibility, and detection of RS phytochemicals. A comprehensive investigation on the metabolic effects of RS in pigs has not been reported.

In a recent feeding trial, the performance of pigs fed the control diet and RSF, including their physiological status and digestion efficiency, was compared, and the results have been reported (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017). Feeding RSF did not affect the histomorphology of ileum and colon, but enlarged the thyroid gland. In addition, RSF reduced the apparent ileal digestibility (AID) and total tract digestibility of energy and nutrients, which coincided with a decreased trypsin activity in the jejunum. The AID of crude protein, total AA, and all individual AA (except for Met) were decreased by the RSF (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017). In this study, the metabolic effects of RSF were further assessed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS)-based metabolomic analysis of digesta, serum, and tissue samples collected from this feeding trial. The metabolites associated with RSF treatment were identified and characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The protocol of feeding trial in this study was reviewed and approved by the Norwegian Food Safety Authority.

Chemicals and Reagents

The protocol of feeding trial in this study was reviewed and approved by the Norwegian Food Safety Authority. Amino acid standards, n-butanol, and sodium pyruvate were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); LC–MS-grade water, acetonitrile (ACN), and formic acid were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Houston, TX); 2,2′-dipyridyl disulfide (DPDS) was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Santa Ana, CA); dansyl chloride (DC) was purchased from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ); 2-hydrazinoquinoline (HQ) and triphenylphosphine (TPP) were obtained from Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA), and p-chlorophenylalanine was from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA).

Animals, Dietary Treatments, and Sample Collection

The compositions of control and RSF diets, as well as the design, procedures, and methods of animal feeding, have been reported (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017). Briefly, 40 Norwegian Landrace castrated pigs (17.8 ± 2.7 kg initial BW) were assigned to 1 of 2 dietary treatments (20 pigs/diet) at the experimental farm of the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. Dietary treatments consisted of feeding an soybean meal (SBM)-based control diet or an RSF where SBM was partially replaced with high-fiber RS coproducts. High-fiber RS coproducts were to increase the difference in fiber content and fiber composition between the diets (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017). These coproducts consisted of 20% of a coarse fraction from air-classified RSM and 4% of pure RS hulls. Pigs were fed twice daily an amount of their respective experimental diets equivalent to 3.5% of BW. After 3 wk of feeding, the pigs were time fed and sacrificed, and digesta samples from 5 different sites along the intestinal tract (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon), along with serum and liver samples were collected, snap frozen, and stored at −80 °C for metabolomic analysis.

Metabolomics

The LC–MS-based metabolomic analysis comprised sample preparation, chemical derivatization, LC–MS analysis, data deconvolution and processing, multivariate data analysis (MDA), and marker characterization and quantification as described previously (Chen et al., 2007).

Sample preparation.

Digesta samples (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon) were prepared by mixing with 50% aqueous ACN in 1:9 (wt/vol) ratio and then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min to obtain digesta extract supernatants. For serum samples, deproteinization was conducted by mixing 1 volume of serum with 19 volumes of 66% aqueous ACN and then centrifuging at 18,000 × g for 10 min to obtain the supernatants. Liver tissue samples were fractionated using a modified Bligh and Dyer method (Bligh and Dyer, 1959). Briefly, 100 mg of liver sample were homogenized in 0.5 mL of methanol and then mixed with 0.5 mL of chloroform and 0.4 mL of deionized water. After 10-min centrifugation at 18,000 × g, the upper aqueous fraction was harvested and the chloroform fraction was dried with nitrogen gas and then reconstituted in n-butanol.

Chemical derivatization.

For detecting metabolites containing amino functional groups in their structure, the samples were derivatized with DC prior to the LC–MS analysis. Briefly, 5 μL of sample or standard was mixed with 5 μL of 100 μmol/L p-chlorophenylalanine (internal standard), 50 μL of 10 mmol/L sodium carbonate, and 100 μL of DC solution (3 mg/mL in acetone). The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 15 min and centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was transferred into a sample vial for LC–MS analysis. Samples were derivatized with HQ prior to the LC–MS analysis to detect carboxylic acids, aldehydes, and ketones (Lu et al., 2013). Briefly, 2 μL of sample was added into a 100 μL of freshly prepared ACN solution containing 1 mmol/L DPDS, 1 mmol/L TPP, and 1 mmol/L HQ. The reaction mixture was incubated at 60 °C for 30 min, chilled on ice, and then mixed with 100 μL of ice-cold deionized water. After centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was transferred into an HPLC vial for LC–MS analysis.

Conditions of LC–MS analysis.

Comprehensive coverage of the metabolome was achieved using 4 different LC–MS conditions to analyze lipids and hydrophilic metabolites, as well as HQ- and DC-derivatized metabolites in digesta, serum, and liver extracts. A 5 μL aliquot was injected into an ultraperformance liquid chromatography–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOFMS) system (Waters, Milford, MA) and separated by a BEH C18 column (Waters) with a gradient of mobile phase ranging from water to 95% aqueous ACN containing 0.1% formic acid over a 10-min run. Capillary voltage and cone voltage for electrospray ionization were maintained at 3 kV and 30 V for positive mode detection, respectively. Source temperature and desolvation temperature were set at 120 and 350 °C, respectively. Nitrogen was used as both cone gas (50 L/h) and desolvation gas (600 L/h), and argon was used as collision gas. For accurate mass measurement, the mass spectrometer was calibrated with sodium formate solution (range m/z 50 to 1,000) and monitored by the intermittent injection of the lock mass leucine enkephalin ([M + H]+ = 556.2771 m/z) in real time. Mass chromatograms and mass spectral data were acquired and processed by MassLynx software (Waters) in centroided format. Additional structural information was obtained by tandem MS (MS/MS) fragmentation with collision energies ranging from 15 to 40 eV.

Data analysis and visualization.

After data acquisition in the UPLC-QTOFMS system, chromatographic and spectral data of samples were deconvoluted by MarkerLynx software (Waters) to provide a multivariate data matrix containing information on sample identity, ion identity (retention time and m/z), and ion abundance. The abundance of each ion was calculated by normalizing the single ion counts vs. the total ion counts in the entire chromatogram. The data matrix was then exported into SIMCA-P+ software (Umetrics, Kinnelon, NJ) and transformed by Pareto scaling. Multivariate data analysis, including principal components analysis (PCA) and partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), was used to model the digesta, serum, and liver samples for the control and RS treatment groups. Metabolite markers were identified by analyzing ions contributing to sample separation in MDA models. After Z score transformation, the concentrations or relative abundances of identified metabolite markers in the samples were presented in heat maps generated by the R program (http://www.R-project.org), and correlations among these metabolite markers were defined by hierarchical clustering analysis.

Characterization, quantification, and pathway analysis of metabolite markers.

The chemical identities of metabolite markers were determined by accurate mass measurement, using elemental composition analysis, by searching the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Lipid Maps databases using MassTRIX search engine (http://masstrix3.helmholtz-muenchen.de/masstrix3/; Suhre and Schmitt-Kopplin, 2008), as well as MS/MS fragmentation and comparisons with authentic standards if available. Individual metabolite concentrations were determined by fitting the ratio between the peak area of each metabolite and the peak area of the internal standard with a standard curve using QuanLynx software (Waters). The relevant pathway analysis of metabolite markers was performed by MetaboAnalyst 3.0 (www.metaboanalyst.ca) using KEGG pathway database.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis of metabolomic parameters was performed as 2-tailed Student’s t tests for unpaired data. Results are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between dietary treatments were considered significant if P < 0.05 and were considered a trend if the P value was between 0.05 and 0.10.

RESULTS

Effects of RSF on Digesta Metabolite Composition in Small and Large Intestines

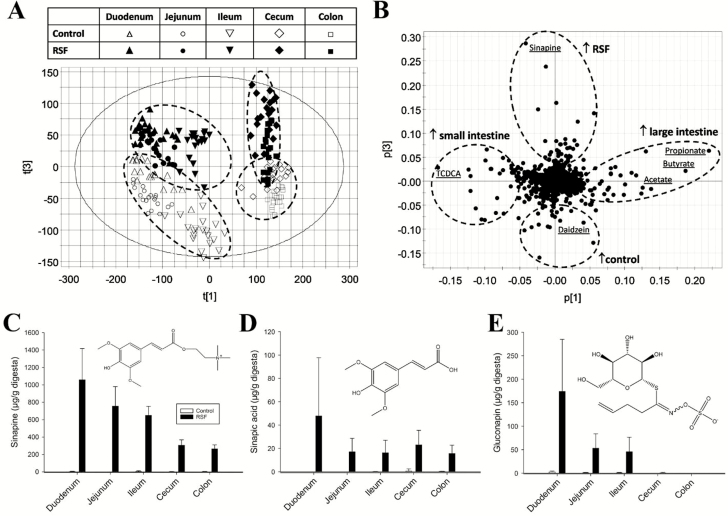

A comprehensive coverage of small-molecule nutrients and metabolites in digesta extracts, including phytochemicals, AA, organic acids, bile acids, and microbial metabolites, was achieved through a combination of chemical derivatization, and optimized chromatographic and spectroscopic conditions. In the PCA model of pooled LC–MS data, small intestine samples (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum) from both dietary treatments were separated clearly from their corresponding large intestine samples (cecum and colon) along the principal component (PC) 1 of the model (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the control samples from all the intestinal sites were also separated from their corresponding RSF samples along the PC 3 of the model (Fig. 1A). The markers contributing to the separation between the control and RSF samples, as well as the markers that changed along the intestinal tract, were revealed in the loadings plot, and further characterized by structural and quantitative analyses (Fig. 1B). Phytochemicals from RS and soybean were the major contributors to the differences between digesta samples from the 2 dietary treatments. Sinapine, sinapic acid, and gluconapin were identified as exposure markers of RSF because of their presence in the digesta of the pigs fed RSF and their near absence in the digesta of the pigs fed the control diet (Fig. 1C–E). Sinapic acid and sinapine, the choline conjugate of sinapic acid, were present along the entire intestinal tract after RSF feeding (Fig. 1C and D). By contrast, gluconapin, a glucosinolate, was mainly present in the small intestine, but nearly absent in the large intestine (Fig. 1E). Daidzein, a soy isoflavone, was positively correlated to control feeding because of its high abundance in the ileum and cecum of control pigs as compared to the RSF pigs (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Identification of exposure markers through metabolomic modeling of digesta samples after feeding young pigs with soybean-based control or rapeseed-based diets for 3 wk. Data from liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC–MS) analysis of digesta samples (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon) were processed by principal component analysis (PCA) for identifying rapeseed-induced metabolic changes and temporal–spatial distribution of metabolites along the intestinal tract. Concentration and distribution of rapeseed phytochemicals across the intestine were determined. (A) Scores plot of the PCA model. (B) Loadings plot of the PCA model. Major metabolites contributing to the separation between the control and rapeseed samples and the separation between the small and large intestine samples are labeled. ↑ indicates positive correlation. (C) Sinapine. (D) Sinapic acid. (E) Gluconapin.

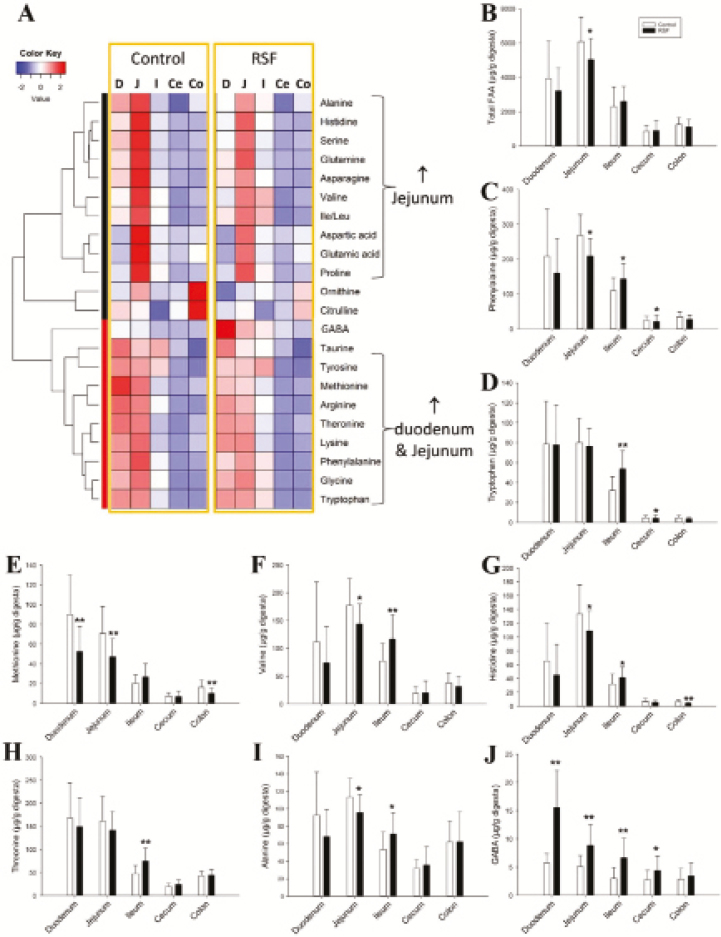

Distribution of free AA (FAA) along the intestinal tract was assessed by quantitative analysis and clustering analysis, resulting in the observation of 2 similar clusters of proteinogenic AA for both dietary treatments in the heat map (Fig. 2A). One AA cluster, including Gly, Thr, Met, Lys, Arg, and aromatic AA (Phe, Tyr, and Trp), was more abundant in both duodenum and jejunum, while the other cluster, including Ala, His, Ser, Pro, branched-chain AA (Val, Leu, Ile), and acidic AA (Asp, Asn, Glu, and Gln), had higher concentrations in jejunum (Fig. 3A). Subtle differences in the distribution of proteinogenic AA were observed between the 2 dietary treatments (Supplementary Table S1). Compared to the control, the RSF pigs had lesser concentrations (P < 0.05) of total AA, Phe, Met, Val, His, and Ala in jejunum, but greater concentrations (P < 0.05) of Phe, Trp, Val, His, Thr, and Ala in the ileum (Fig. 2B–I). Interestingly, from duodenum to cecum, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a nonproteinogenic AA and also a neurotransmitter, was present in greater (P < 0.05) concentration in all section of the gastrointestinal of pigs fed RSF compared to the control pigs (Fig. 2J). The concentrations of GABA in control and RSF diets were further determined as 0.12 and 0.26 g/kg, respectively.

Figure 2.

Influences of rapeseed on the distribution of free AA (FAA) along the intestinal tract: (D = duodenum, J = jejunum, I = ileum, Ce = cecum, Co = colon). Concentrations of FAA along the intestinal tract were quantified and then processed by clustering analysis. (A) Heat map of the FAA distribution along the intestinal tract. ↑ indicates positive correlation. (B) Total free AA (FAA). (C) Phenylalanine. (D) Tryptophan. (E) Methionine. (F) Valine. (G) Histidine. (H) Threonine. (I) Alanine. (J) Gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). Significant differences between the control and rapeseed feed (RSF) samples are marked by * (P < 0.05) and ** (P < 0.01).

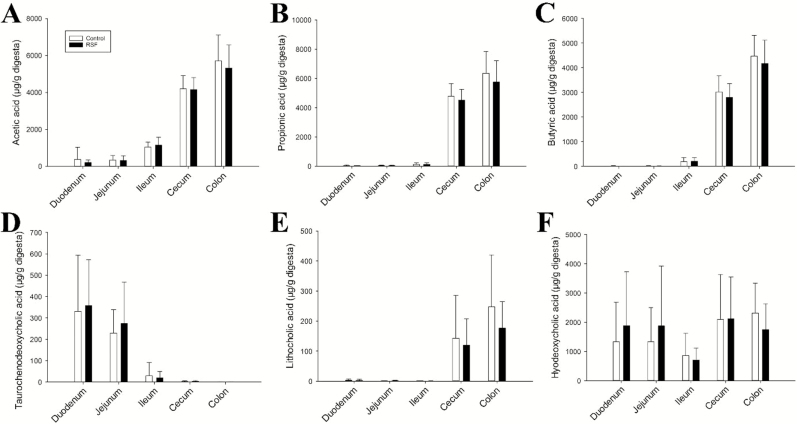

Figure 3.

Distribution of metabolites related to microbial metabolism in the intestine after feeding young pigs with soybean meal-based control or rapeseed feed (RSF) for 3 wk. Concentrations of short-chain fatty acids and bile acids were determined. (A) Acetic acid. (B) Propionic acid. (C) Butyric acid. (D) Hyodeoxycholic acid. (G) Lithocholic acid. (H) Taurochenodeoxycholic acid.

The influence of RS feeding on the metabolism of the intestinal microbiota was evaluated by measuring the concentrations of major short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) and bile acids in digesta, which are 2 groups of metabolites either formed or metabolized by the microbiota. The results from quantitative analysis of SCFA and bile acids showed no differences between the 2 dietary treatments (Fig. 3A–F). As expected, the concentrations of acetic, propionic, and butyric acids were greater in the large intestine than in the small intestine of both dietary treatments (Fig. 3A–C). The concentration of taurochenodeoxycholic acid, a primary bile acid, was greater in the small intestine than in the large intestine of pigs fed both dietary treatments (Fig. 3D). By contrast, the concentration of lithocholic acid, a secondary bile acid, was greater (P < 0.05) in the large intestine than in the small intestine of pigs fed both dietary treatments (Fig. 3E). Considerable amounts of hyodeoxycholic acid were detected along the entire intestinal tract of pigs fed both diets (Fig. 3F).

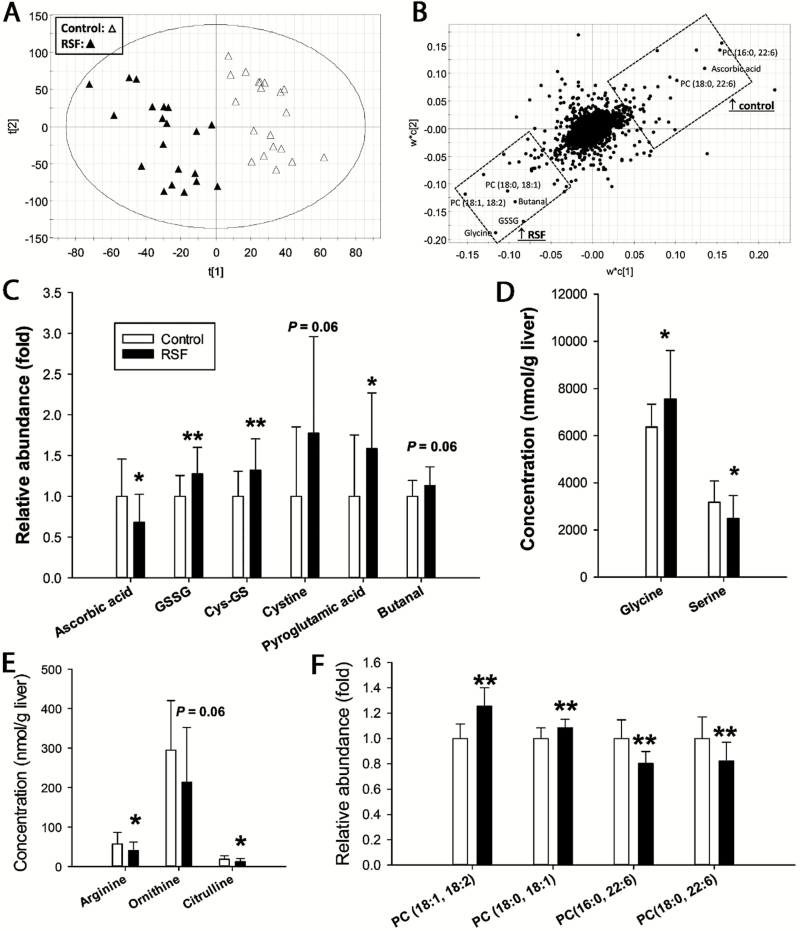

Effects of RSF on the Hepatic Metabolome

Metabolomic analysis of liver extracts revealed RS-induced metabolic changes in the liver because control and RSF samples from individual pigs were separated in a PLS-DA model (Fig. 4A). The hepatic metabolites contributing to the separation of the samples from the 2 dietary treatments were identified in the loadings plot and structurally elucidated by authentic standards or tandem mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 4B). Feeding RSF affected multiple metabolites associated with oxidative stress and redox balance. Decreased concentration of ascorbic acid (P < 0.05), an antioxidant, was observed in the livers of RSF pigs, while increased concentrations of oxidized disulfide metabolites, including oxidized glutathione (GSSG, P < 0.01), cysteine-glutathione (Cys-GS, P < 0.01), and cysteine (P = 0.06), were observed in the same samples (Fig. 4C). Moreover, pyroglutamate (P < 0.05), a metabolite marker of oxidative stress, and butanal (P = 0.06), a degradation product of in vivo lipid peroxidation, were also increased by RSF (Fig. 4C). Total FAA and most individual FAA in the liver were comparable between control and RSF treatments (Supplementary Table S2). Feeding the RSF diet affected 2 major donors of 1-carbon units to the folate cycle differently by increasing (P < 0.05) glycine while decreasing (P < 0.05) serine concentrations in the liver (Fig. 4D). The concentrations of arginine (P < 0.05), ornithine (P = 0.06), and citrulline (P < 0.05), which are involved in the urea cycle, were reduced in the liver of RSF pigs compared to that of control pigs (Fig. 4E). The composition of phospholipids in the liver was also affected by RSF, because RSF increased (P < 0.01) the levels of 2 C18 fatty acid–containing phosphatidylcholines (PC), PC (18:0, 18:1) and PC (18:1, 18:2), and decreased (P < 0.01) the concentrations of 2 docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)-containing PC, PC (16:0, 22:6) and PC (18:0, 22:6) (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Influences of rapeseed feeding on pig hepatic metabolome. Data from liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC–MS) analysis of aqueous and lipid fractions of liver samples were processed by partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) to identify rapeseed-induced metabolic changes in the liver. (A) Scores plot of PLS-DA model. (B) Loadings plot of PLS-DA model. ↑ indicates positive correlation. Major metabolites contributing to the separation between the soybean meal-control and the rapeseed samples are labeled. (C) Metabolites associated with redox balance. (D) Serine and glycine. (E) Urea cycle metabolites. (F) Phosphatidylcholine metabolites. Significant differences between the control and RSF samples are marked by * (P < 0.05) and ** (P < 0.01).

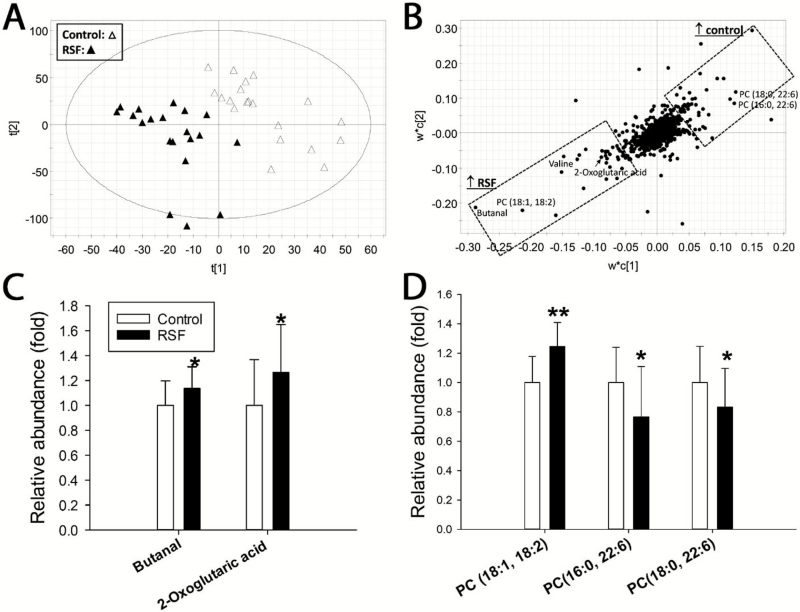

Effects of RSF on the Serum Metabolome

Quantitative analysis of serum FAA showed that RSF resulted in a greater concentration of total serum FAA, which were mainly due to the increases of Glu, Gln, Val, and Thr in serum (Supplementary Table S3). Metabolomic analysis revealed a clear separation between the control and RSF treatments in serum samples in the scores plot of a PLS-DA model (Fig. 5A). Serum metabolites contributing to the separation between the 2 dietary treatments were identified in the loadings plot and structurally elucidated by authentic standards or tandem mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 5B). Butanal and 2-oxoglutaric acid were identified as markers of RSF because their concentrations were greater (P < 0.05) in the serum of these pigs compared with the control (Fig. 5C). In addition, 3 of the 4 phospholipid markers identified in the liver after RS feeding changed consistently in serum, with increased (P < 0.01) PC (18:1, 18:2) and reduced (P < 0.05) PC (16:0, 22:6) and PC (18:0, 22:6) (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Influences of rapeseed feeding on pig serum metabolome. Data from liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC–MS) analysis of serum samples were processed by partial least squares-discriminatory analysis (PLS-DA) for identifying rapeseed-induced metabolic changes in serum. (A) Scores plot of PLS-DA model. (B) Loadings plot of PLS-DA model. Major metabolites contributing to the separation between the soybean meal-control and the rapeseed samples are labeled. ↑ indicates positive correlation. (C) Metabolites associated with redox balance. (D) Phosphatidylcholine metabolites. Significant differences between the control and RSF samples are marked by * (P < 0.05) and ** (P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Sustainability of pork production demands new approaches to reduce carbon, water, and land consumption. Replacing soybean meal with RSF decreases the environmental impact of pork production (van Zanten et al., 2015). However, antinutritional factors in RS and their negative effects on growth performance limit the inclusion of RSF in swine diets. Because metabolism is the foundation of nutrient utilization and growth performance, examining the metabolic effects of RSF could guide the intervention efforts that aim to help pigs cope with antinutritional factors in RSF.

Due to inherent differences between RS and soybean in nutrient and phytochemical compositions, feeding pigs with the products of these 2 oilseeds are expected to yield different metabolic profiles. Metabolomic analysis in this study confirmed this hypothesis through modeling the digesta, liver, and serum samples from young pigs fed SBM- and RS-based diets. The extensive impacts of RS on the metabolome of young pigs are reflected by the structural and functional diversity of the metabolites responsive to RSF. Discussions on the significance of these metabolites in monitoring RS feeding and their potential associations with the performance and the health of the pigs are based on the sources and functions of these metabolites, including exposure markers, microbial metabolites, protein digestion and amino acid metabolism, and redox status.

Phytochemicals as Exposure Markers

Detecting the presence of phenolics and glucosinolates in digesta of pigs fed the RS diet was expected because they are the most abundant and bioactive phytochemicals in RS (Mailer et al., 2008). However, the concentrations of these components in pig digesta and their distribution along the segments of small and large intestines have not been reported in previous studies. In the present study, digesta samples from 5 sites of the small and large intestines were separated in a multivariate model, largely based on their anatomical locations in the intestinal tract (Fig. 1A). This pattern of distribution reflected gradual transformation of feed components, including phytochemicals, along the intestinal tract through digestion, absorption, microbial metabolism, and excretion. A prominent observation from the quantitative analysis of RS phytochemicals was the detection of significant amount of sinapine (up to 1 mg/g wet weight) in the digesta along the entire intestinal tract of RSF pigs. This is consistent with the fact that sinapine is abundant in RS and canola seeds, accounting for about 80% of their total phenolic content, and present at a concentration of about 10 g/kg in defatted canola seeds and press cake (Khattab et al., 2010; Nićiforović and Abramovič, 2014). Sinapic acid was also detected in the digesta along the entire intestinal tract in the RSF pigs. This observation was in contrast to the observation in broiler chickens, in which sinapic acid, up to 0.1% (wt/wt) of feed, was almost completely absorbed in the small intestine, with little presence in the large intestine (Qiao et al., 2008). Because sinapine is the choline ester of sinapic acid, continuous hydrolysis of sinapine in RSF pigs was likely a major source of the sinapic acid detected along the intestinal tract, including the large intestine. Gluconapin is the most abundant glucosinolate in RS (Mawson et al., 1993a). The consistent presence of gluconapin in the small intestine and its disappearance in the large intestine agrees with previous observations, indicating that glucosinolates are resistant to digestive enzymes, but susceptible to the myrosinase-like activities of cecal microbiota, such as lactic acid bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, Bifidobacterium, and Bacteroides spp (Lai et al., 2010; Mullaney et al., 2013). It should be noted that the degradation of gluconapin and other glucosinolates in the cecum can produce corresponding isothiocyanates, which are bioactive compounds that can mediate antioxidant responses in the body (Mawson et al., 1993b). The identification of daidzein as a robust exposure marker in the digesta of control pigs was also expected because daidzein is an abundant and naturally occurring isoflavone in legumes (Jung et al., 2000). The observation of greater abundance of daidzein in the ileum and cecum and less abundance in the duodenum, jejunum, and colon may reflect the fact that daidzein, as an aglycone of soybean isoflavones, is formed through β-glucosidases-mediated hydrolysis in jejunum and then degraded by microbial metabolism in cecum and colon (Day et al., 1998; Zubik and Meydani, 2003).

Microbial Metabolites

The prominence of microbial metabolites, especially SCFA and bile acids, in the chemical composition of digesta was illustrated by their clear contribution to the separation of the small intestine samples from the large intestine sample in the metabolomic model (Fig. 1A and B). The distribution of SCFA, primary bile acids, and secondary bile acids was consistent with the localization and metabolic function of the microbiota in the large intestine. The RSF diet in this study is a high-fiber diet based on its levels of neutral detergent fiber and acid detergent fiber (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017). Considering the extensive interactions between fiber and gut microbiota (Simpson and Campbell, 2015), including the metabolic interactions (Koh et al., 2016), changes of microbial metabolites in the digesta of RSF pigs were initially expected. However, no differences in the concentrations of SCFA and bile acids in the digesta were observed between the 2 dietary treatments. This observation, together with the fact that the RSF diet did not affect the histomorphology of the ileum and colon of the pigs (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017), suggests that the quantity and/or the type of fiber in the RSF diet might not significantly affect the metabolic functions of microbiota as well as the intestinal tissues housing the microbiota during the 3-wk feeding period. Whether long-term feeding of RS could affect the microbiota and microbial metabolism requires further investigation.

Protein Digestion and AA Metabolism

An observation associated with protein digestion in the intestinal tract was the presence of 2 major clusters of FAA in the heat map of FAA concentrations of the digesta samples from both dietary treatments (Fig. 3A). One FAA cluster was present in greater concentrations in jejunum, while the other FAA cluster was present in greater concentrations in both duodenum and jejunum. This observation indicates that individual AA do not share the same temporal-spatial profile along the intestinal tract when released from the digestion of the proteins in these 2 diets. This pattern of FAA clustering may be the result of different site-specific proteolytic enzyme activities and different efficiency in site-specific AA absorption due to the distribution of proteolytic enzymes and transporters for individual AA in the intestinal tract (Erickson and Kim, 1990). Furthermore, the FAA pool only explains a small fraction of the total AA absorption because a large proportion of AA is directly absorbed as dipeptides and tripeptides (Gilbert et al., 2008).

The control and RSF diets had relatively comparable levels and composition of AA (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017). However, differences in the FAA profiles of digesta, liver, and serum samples were observed between 2 dietary groups (Supplementary Table S1–S3). The lower concentration of total FAA in the jejunal digesta of the RSF pigs, together with the reduced AID of CP and AA observed in these pigs, indicates a delay in the protein digestion process in these pigs. This is supported by the reduced trypsin activity in the jejunal digesta of the RSF pigs reported before (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017). Interestingly, the delay and reduction in protein digestion induced by RS feeding did not lead to significant changes in the concentration of total FAA in the liver. In fact, greater concentrations of total FAA and specific individual AA were observed in the serum of the RSF pigs. The increase in the serum FAA pool may be due to reduced protein synthesis, a metabolic process directly associated with growth performance, or to an increase in protein degradation. The latter possibility is supported by the upregulation of the hepatic urea cycle observed in the RSF pigs, as indicated by the reduced concentrations of intermediates of the urea cycle (Arg, Cit, and Orn) in the liver and the increase of nitrogen carriers in the serum (Glu and Gln) of the RSF pigs. In addition to the changes in total FAA, specific individual AA were also affected by RS feeding. Hepatic-free Ser and Gly, 2 important intermediate metabolites in 1-carbon metabolism, were decreased and increased by the RS diet, respectively. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase is the primary enzyme in the conversion of serine into glycine (Narkewicz et al., 1996). Whether RS feeding could affect the expression level and the activity of this enzyme remains to be examined. Moreover, GABA from RSF dramatically increased the GABA level from duodenum to cecum, as well as in the liver. GABA, as a minor nonproteinogenic AA and an inhibitory neurotransmitter, is found in many plants, including Brassica species such as Chinese cabbage (Bouché and Fromm, 2004; Kim et al., 2013). GABA receptors are expressed along the intestinal tract and modulate both motor and secretory activities (Krantis, 2000; Auteri et al., 2015). Interestingly, sinapic acid, the most abundant phenolic compound in RS, was reported to potentiate GABA signals (Yoon et al., 2007). Further investigation is required to address whether the increase of GABA and its copresence with sinapic acid in the intestinal lumen could contribute to the RS-elicited changes in AA digestibility.

Redox Status

The decrease of ascorbic acid and the increase of multiple oxidized metabolites, including oxidized thiols and pyroglutamate, were the most prominent effects of RSF on hepatic and serum metabolome. These observations clearly indicate that RSF can disrupt redox balance in pigs, which might contribute to the organ toxicity observed in previous RS feeding experiments (Mawson et al., 1994b). On the other hand, our results are in contrast to the antioxidant properties assigned to certain RS components based on the following facts: 1) RS is a rich source of vitamin C (Krumbein et al., 2005); 2) sinapic acid and other phenolic acids in RS can function as antioxidants (Gaspar et al., 2010; Nićiforović and Abramovič, 2014); and 3) isothiocyanates, the degradation products of glucosinolates, are robust inducers of antioxidant enzymes (de Figueiredo et al., 2013). A plausible explanation for this phenomenon is that the dose of RS coproducts in the present experiment might be too high for young pigs because enlarged thyroid glands were observed in these RSF-fed pigs (Pérez de Nanclares et al., 2017). It is likely that this goitrogenic dose caused a strong pro-oxidant effect, overriding the antioxidant activity of RS components. Future studies using a dose titration of RS and antioxidants are needed to validate this hypothesis. Despite the apparent redox imbalance in the RSF pigs, short-term RS feeding did not affect the growth of the pigs in the current study. However, negative influences of RS feeding on growth performance have been observed in other feeding experiments with longer terms (Kracht et al., 2004; Choi et al., 2015), as well as in our following long-term feeding study (data not shown). The intermediate events occurring between the changes in redox status induced by feeding RS and the changes in feed efficiency and growth performance remain to be elucidated.

Lipids are the cellular components sensitive to disruption of redox balance. Butanal, as an aldehydic product of lipid peroxidation (Esterbauer et al., 1982), was increased in serum and the liver by RSF in this study. Analyses of phospholipids in the liver and serum revealed that RSF increased the levels of oleic acid–containing PC, which is consistent with the fact that RS (canola) oil contains more oleic acid than soybean oil. However, RSF decreased the levels of DHA-containing PC in the liver and serum, which is in contrast to the fact that RS oil contains more α-linolenic acid, a precursor of DHA, than soybean oil (USDA Food Composition Databases, https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/). A plausible explanation for this phenomenon is that both α-linolenic acid and DHA, which are omega-3 fatty acids, are more susceptible to lipid peroxidation compared with oleic acid. In fact, when RS products were fed together with selenium, a cofactor of the glutathione peroxidase complex, the concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids, including DHA, were increased in meat and back fat of growing-finishing pigs (Gjerlaug-Enger et al., 2015). Therefore, upregulation of antioxidant system might be an effective approach to improve the responses and performance when feeding RS diets to pigs.

In summary, the disposition of RS phytochemicals and nutrients, as well as their influences on microbial, lipid, and antioxidant metabolism, was examined through both untargeted metabolomic analysis and targeted quantitative analysis of digesta, liver, and serum samples from young pigs fed an RS diet compared with an SBM-control diet. Rapeseed feeding had limited effects on microbial and AA metabolism, but it had a prominent negative influence on the redox status of young pigs. Therefore, identifying the causes of redox imbalance, investigating its impact on feed efficiency and growth performance, and exploring dietary interventions for alleviation will be meaningful topics in further research on how to use RS coproducts as a source of energy, protein, and other nutrients in animal feeds.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Animal Frontiers online.

Footnotes

This study was financially supported by FeedMileage-Efficient use of Feed Resources for a Sustainable Norwegian Food Production (Research Council of Norway, Oslo, Norway; grant no. 233685/E50), and Foods of Norway, Centre for Research-based Innovation (Research Council of Norway; grant no. 237841/030). The research by C.C. is partially supported by a USDA Agricultural Experiment Station project MIN-18-092.

LITERATURE CITED

- Auteri M., Zizzo M. G., and Serio R.. 2015. GABA and GABA receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: From motility to inflammation. Pharmacol. Res. 93:11–21. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh E. G., and Dyer W. J.. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37:911–917. doi:10.1139/o59-099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouché N., and Fromm H.. 2004. GABA in plants: just a metabolite?Trends Plant Sci. 9:110–115. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2004.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Gonzalez F. J., and Idle J. R.. 2007. LC-MS-based metabolomics in drug metabolism. Drug Metab. Rev. 39:581–597. doi:10.1080/03602530701497804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. B., Jeong J. H., Kim D. H., Lee Y., Kwon H., and Kim Y. Y.. 2015. Influence of rapeseed meal on growth performance, blood profiles, nutrient digestibility and economic benefit of growing-finishing pigs. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 28:1345–1353. doi:10.5713/ajas.14.0802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day A. J., DuPont M. S., Ridley S., Rhodes M., Rhodes M. J., Morgan M. R., and Williamson G.. 1998. Deglycosylation of flavonoid and isoflavonoid glycosides by human small intestine and liver beta-glucosidase activity. FEBS Lett. 436:71–75. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01101-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Figueiredo S. M., Filho S. A., Nogueira-Machado J. A., and Caligiorne R. B.. 2013. The anti-oxidant properties of isothiocyanates: A review. Recent Pat. Endocr. Metab. Immune Drug Discov. 7:213–225. doi:10.2174/18722148113079990011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson R. H., and Kim Y. S.. 1990. Digestion and absorption of dietary protein. Annu. Rev. Med. 41:133–139. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.41.020190.001025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterbauer H., K. H. Cheeseman M. U. Dianzani G. Poli, and Slater T. F.. 1982. Separation and characterization of the aldehydic products of lipid peroxidation stimulated by ADP-Fe2+ in rat liver microsomes. Biochem. J. 208:129–140. doi:10.1042/bj2080129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar A., Martins M., Silva P., Garrido E. M., Garrido J., Firuzi O., Miri R., Saso L., and Borges F.. 2010. Dietary phenolic acids and derivatives: Evaluation of the antioxidant activity of sinapic acid and its alkyl esters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58:11273–11280. doi:10.1021/jf103075r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert E. R., Wong E. A., and Webb K. E. Jr. 2008. Board-invited review: Peptide absorption and utilization: Implications for animal nutrition and health. J. Anim. Sci. 86:2135–2155. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerlaug-Enger E., Haug A., Gaarder M., Ljøkjel K., Stenseth R. S., Sigfridson K., Egelandsdal B., Saarem K., and Berg P.. 2015. Pig feeds rich in rapeseed products and organic selenium increased omega-3 fatty acids and selenium in pork meat and backfat. Food Sci. Nutr. 3:120–128. doi:10.1002/fsn3.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd R. M., and Arthur P. F.. 2009. Physiological basis for residual feed intake. J. Anim. Sci. 87(Suppl 14):E64–E71. doi:10.2527/jas.2008-1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung W., O. Yu S. M. Lau D. P. O’Keefe J. Odell G. Fader, and McGonigle B.. 2000. Identification and expression of isoflavone synthase, the key enzyme for biosynthesis of isoflavones in legumes. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:208–212. doi:10.1038/72671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattab R., Eskin M., Aliani M., and Thiyam U.. 2010. Determination of sinapic acid derivatives in canola extracts using high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 87:147–155. doi:10.1007/s11746-009-1486-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Jung Y., Song B., Bong Y. S., Ryu D. H., Lee K. S., and Hwang G. S.. 2013. Discrimination of cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. Pekinensis) cultivars grown in different geographical areas using ¹H NMR-based metabolomics. Food Chem. 137:68–75. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh A., De Vadder F., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., and Bäckhed F.. 2016. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 165:1332–1345. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kracht W., Dänicke S., Kluge H., Keller K., Matzke W., Hennig U., and Schumann W.. 2004. Effect of dehulling of rapeseed on feed value and nutrient digestibility of rape products in pigs. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 58:389–404. doi:10.1080/00039420400005018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantis A. 2000. GABA in the mammalian enteric nervous system. News Physiol. Sci. 15:284–290. doi:10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.6.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumbein A. B., Schonhof I., and Schreiner M.. 2005. Composition and contents of phytochemicals (glucosinolates, carotenoids and chlorophylls) and ascorbic acid in selected Brassica species (B. juncea, B. rapa subsp. nipposinica var. chinoleifera, B. rapa subsp. chinensis and B. rapa subsp. rapa). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 79:168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lai R. H., Miller M. J., and Jeffery E.. 2010. Glucoraphanin hydrolysis by microbiota in the rat cecum results in sulforaphane absorption. Food Funct. 1:161–166. doi:10.1039/c0fo00110d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Yao D., and Chen C.. 2013. 2-Hydrazinoquinoline as a derivatization agent for LC-MS-based metabolomic investigation of diabetic ketoacidosis. Metabolites 3:993–1010. doi:10.3390/metabo3040993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailer R. J., McFadden A., Ayton J., and Redden B.. 2008. Anti-nutritional components, fibre, sinapine and glucosinolate content, in Australian Canola (Brassica napus L.) Meal. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 85:937–944. [Google Scholar]

- Mawson R., Heaney R. K., Piskuła M., and Kozłowska H.. 1993a. Rapeseed meal-glucosinolates and their antinutritional effects. Part 1. Rapeseed production and chemistry of glucosinolates. Nahrung 37:131–140. doi:10.1002/food.19930370206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawson R., Heaney R. K., Zdunczyk Z., and Kozlowska H.. 1993b. Rapeseed meal-glucosinolates and their antinutritional effects. Part II. Flavour and palatability. Nahrung 37:336–344. doi:10.1002/food.19930370405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawson R., R. K. Heaney Z. Zdunczyk, and Kozłowska H.. 1994a. Rapeseed meal-glucosinolates and their antinutritional effects. Part 4. Goitrogenicity and internal organs abnormalities in animals. Nahrung 38:178–191. doi:10.1002/food.19940380210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawson R., Heaney R. K., Zdunczyk Z., and Kozłowska H.. 1994b. Rapeseed meal-glucosinolates and their antinutritional effects. Part 3. Animal growth and performance. Nahrung 38:167–177. doi:10.1002/food.19940380209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullaney J. A., W. J. Kelly T. K. McGhie J. Ansell, and Heyes J. A.. 2013. Lactic acid bacteria convert glucosinolates to nitriles efficiently yet differently from Enterobacteriaceae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61:3039–3046. doi:10.1021/jf305442j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkewicz M. R., Sauls S. D., Tjoa S. S., Teng C., and Fennessey P. V.. 1996. Evidence for intracellular partitioning of serine and glycine metabolism in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem. J. 313(Pt 3):991–996. doi:10.1042/bj3130991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nićiforović N., and Abramovič H.. 2014. Sinapic acid and its derivatives: Natural sources and bioactivity. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 13:34–51. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblet J., H. Gilbert Y. Jaguelin-Peyraud, and Lebrun T.. 2013. Evidence of genetic variability for digestive efficiency in the growing pig fed a fibrous diet. Animal 7:1259–1264. doi:10.1017/S1751731113000463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez de Nanclares M., Trudeau M. P., Hansen J. Ø., Mydland L. T., Urriola P. E., Shurson G. C., Piercey Åkesson C., Kjos N. P., Arntzen M. Ø., and Øverland M.. 2017. High-fiber rapeseed co-product diet for Norwegian Landrace pigs: Effect on digestibility. Livest. Sci. 203:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2017.06.008 [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H. Y., Dahiya J. P., and Classen H. L.. 2008. Nutritional and physiological effects of dietary sinapic acid (4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy-cinnamic acid) in broiler chickens and its metabolism in the digestive tract. Poult. Sci. 87:719–726. doi:10.3382/ps.2007-00357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski A. 1971. The feed value of rapeseed meal. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 48:863–868. doi:10.1007/BF02609300 [Google Scholar]

- Simpson H. L., and Campbell B. J.. 2015. Review article: Dietary fibre-microbiota interactions. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 42:158–179. doi:10.1111/apt.13248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhre K., and Schmitt-Kopplin P.. 2008. Masstrix: Mass translator into pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W481–W484. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi M. K., and Mishra A. S.. 2007. Glucosinolates in animal nutrition: A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 132:1–27. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2006.03.003 [Google Scholar]

- van Zanten, H. H., P. Bikker, H. Mollenhorst, B. G. Meerburg, I. J. de Boer. 2015. Nov. Environmental impact of replacing soybean meal with rapeseed meal in diets of finishing pigs. Animal. 9(11):1866–1874. doi: 10.1017/S1751731115001469 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yoon B. H., Jung J. W., Lee J. J., Cho Y. W., Jang C. G., Jin C., Oh T. H., and Ryu J. H.. 2007. Anxiolytic-like effects of sinapic acid in mice. Life Sci. 81:234–240. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubik L., and Meydani M.. 2003. Bioavailability of soybean isoflavones from aglycone and glucoside forms in American women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 77:1459–1465. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.6.1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.