Abstract

The spliceosome catalyzes the excision of introns from pre-mRNA in two steps, branching and exon ligation, and is assembled from five small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs; U1, U2, U4, U5, U6) and numerous non-snRNP factors1. For branching, the intron 5'-splice site (5'SS) and the branch point (BP) sequence are selected and brought into the prespliceosome by the U1 and U2 snRNPs1, which is a focal point for the regulation by alternative splicing factors2. The U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP subsequently joins the prespliceosome to form the complete pre-catalytic spliceosome. Recent studies have revealed the structural basis of the branching and exon-ligation reactions3. However, the structural basis of early spliceosome assembly events remains poorly understood4. Here we report the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae prespliceosome at near-atomic resolution. The structure reveals an induced stabilization of the 5'SS in the U1 snRNP, and provides structural insights into the functions of the human alternative splicing factors LUC7-like (yeast Luc7) and TIA-1 (yeast Nam8) that are linked to human disease5,6. In the prespliceosome, the U1 snRNP associates with the U2 snRNP through a stable contact with the U2 3' domain and a transient yeast-specific contact with the U2 SF3b-containing 5' region, leaving its tri-snRNP-binding interface fully exposed. The results suggest mechanisms for 5'SS transfer to the U6 ACAGAGA region within the assembled spliceosome and for its subsequent conversion to the activation-competent B complex spliceosome7,8. Taken together, the data provide a working model to investigate the early steps of spliceosome assembly.

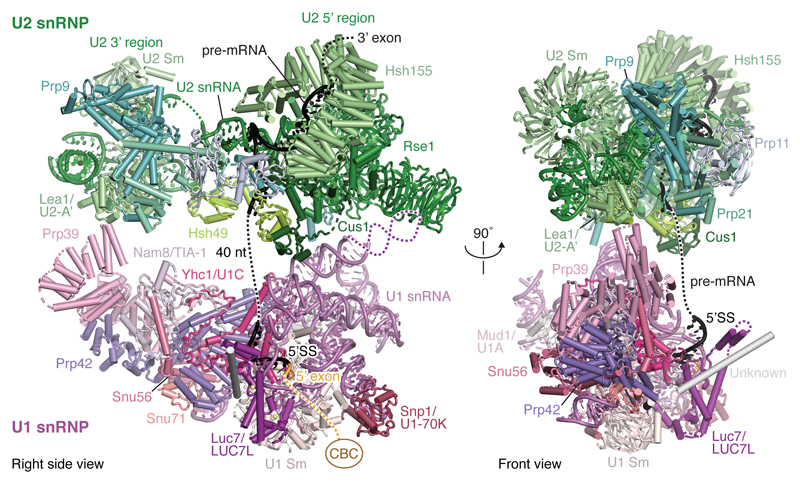

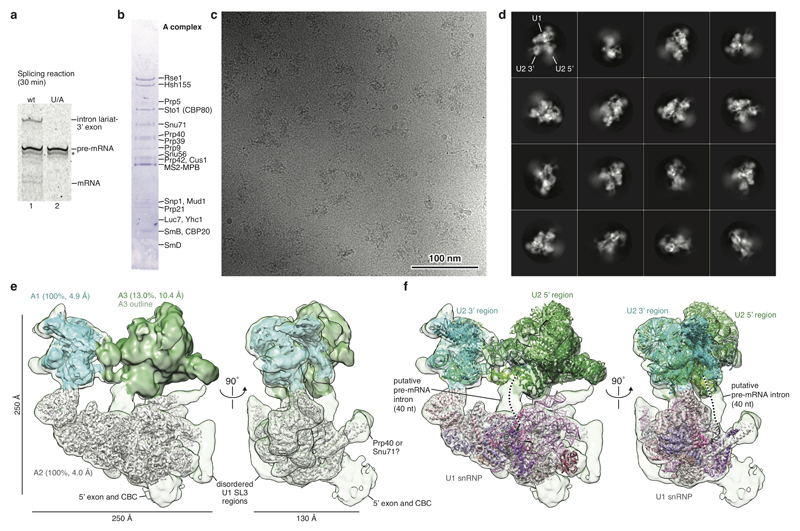

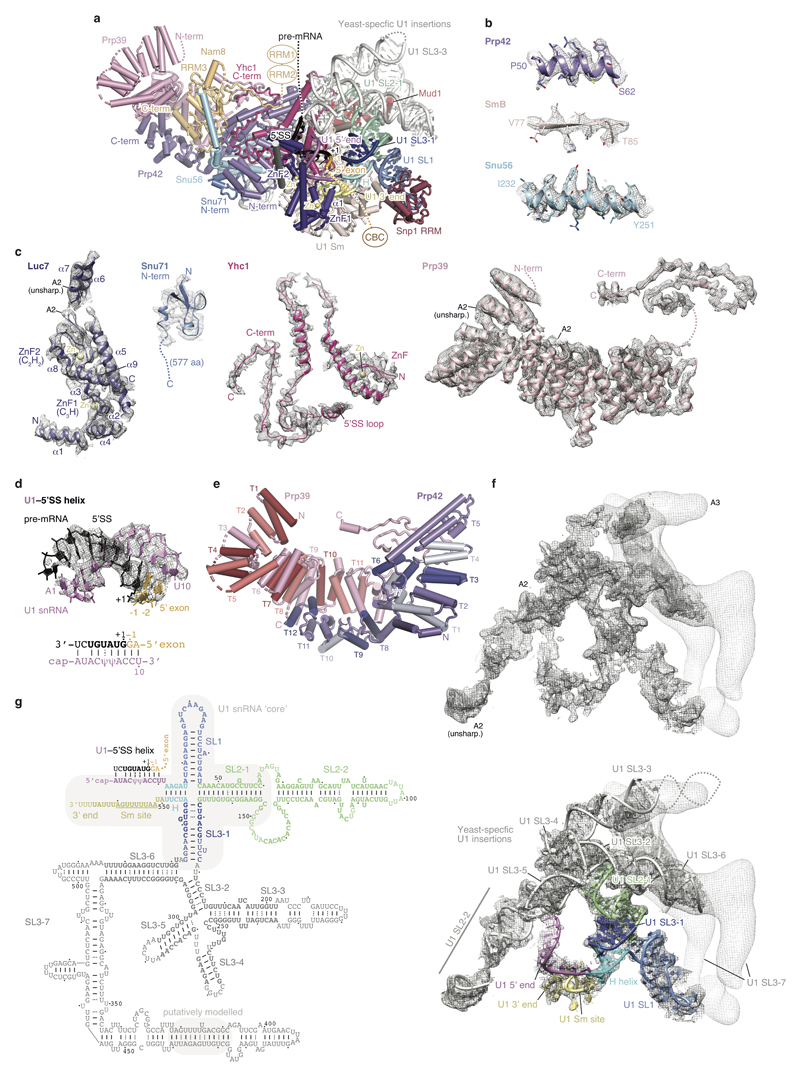

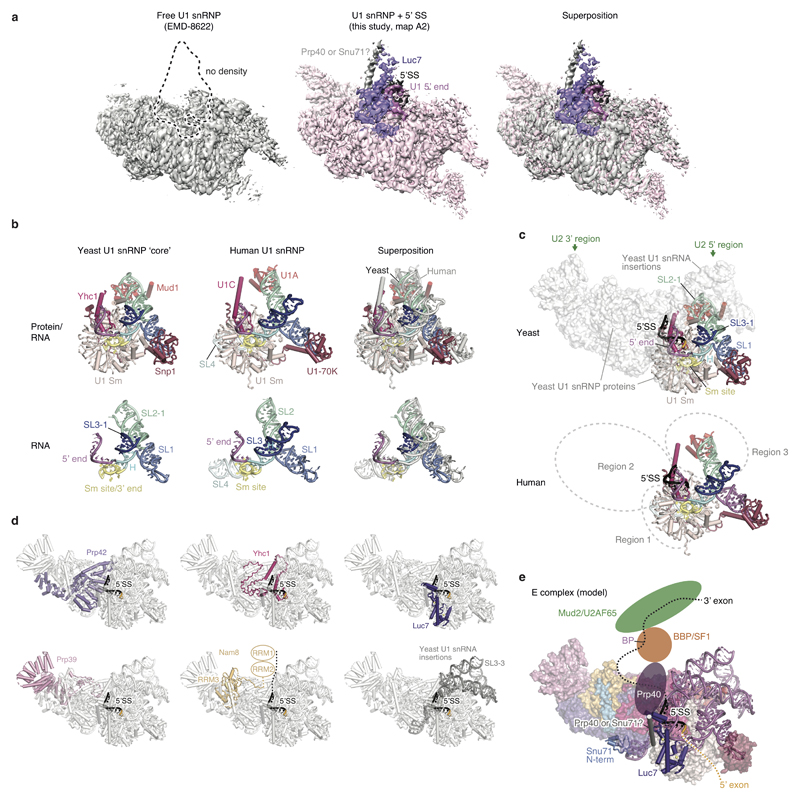

To gain structural insights into early spliceosome assembly, we prepared the yeast prespliceosome A complex on UBC4 pre-mRNA carrying a mutation in the pre-mRNA branch point (BP) sequence, which was previously used to stall the A complex9 (UACUAAC to UACAAAC, where A is the BP adenosine) (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b; Methods). The purified A complex contained stoichiometric amounts of the U1 and U2 snRNP proteins (Extended Data Fig. 1b), and was used to determine cryo-EM densities of the A complex at 4.0 Å (U1 snRNP, map A2) and 4.9-10.4 Å (U2 snRNP, maps A1 and A3) resolution, respectively (Extended Data Figs 1c,d,e, 2, Methods). From these densities we could build a near-complete atomic model of the A complex (Fig. 1, Supplementary videos 1 and 2, supplementary file, Extended Data Fig. 1f), comprising 34 proteins, U1 and U2 snRNAs, and 34 nucleotides of pre-mRNA. The final model lacks the mobile cap-binding complex, Prp5 or the U1 subunit Prp40 (Extended Data Fig. 1b,d,e and Extended Data Table 1). The elongated U1 and U2 snRNPs bind the pre-mRNA 5'SS and BP sequences, respectively, and associate in a parallel manner to form the A complex (Fig. 2a). The U1 snRNP structure contains all essential regions of U1 snRNA and 16 proteins (Fig. 1). The U1 snRNP ‘core’ is highly similar to its human counterpart (Extended Data Figs 3 and 4; ref. 10), comprising the seven-membered Sm ring and orthologues of the human U1 snRNP proteins (Snp1, human U1-70k; Mud1, human U1A; Yhc1, human U1C), and is bound to the peripheral yeast U1 proteins Luc7, Nam8, Prp39, Prp42, Snu56, and Snu71 (ref. 11) (Extended Data Figs 3, 4). The U2 snRNP has a bipartite structure as observed in B complex8, comprising the SF3b subcomplex (‘5' region’) and the U2 3' domain/SF3a subcomplex (‘3' region’) that are organized around the 5' and 3' regions of U2 snRNA, respectively (Figs 1, 2a, Extended Data Fig. 5). The conformation of the U2 5' region is unchanged from the B complex8, where the pre-mRNA BP sequence is base-paired with U2 snRNA and the BP adenosine is bulged out and accommodated in a pocket formed by U2 SF3b subunits Hsh155 and Rds3. After we completed the A complex structure, the cryo-EM structure of the free yeast U1 snRNP was reported12. This model is in good agreement with the U1 snRNP in our A complex structure, but there are important differences12.

Figure 1. Prespliceosome A complex structure.

Two orthogonal views of the yeast A complex structure. Subunits are coloured according to snRNP identity (U1, shades of purple, U2, shades of green), and the pre-mRNA intron (black) and its 5' exon (orange) are highlighted. Orthologous human proteins are shown after the backslash. The location of the cap-binding complex (CBC) is indicated with a brown oval (Extended Data Figure 1d,e).

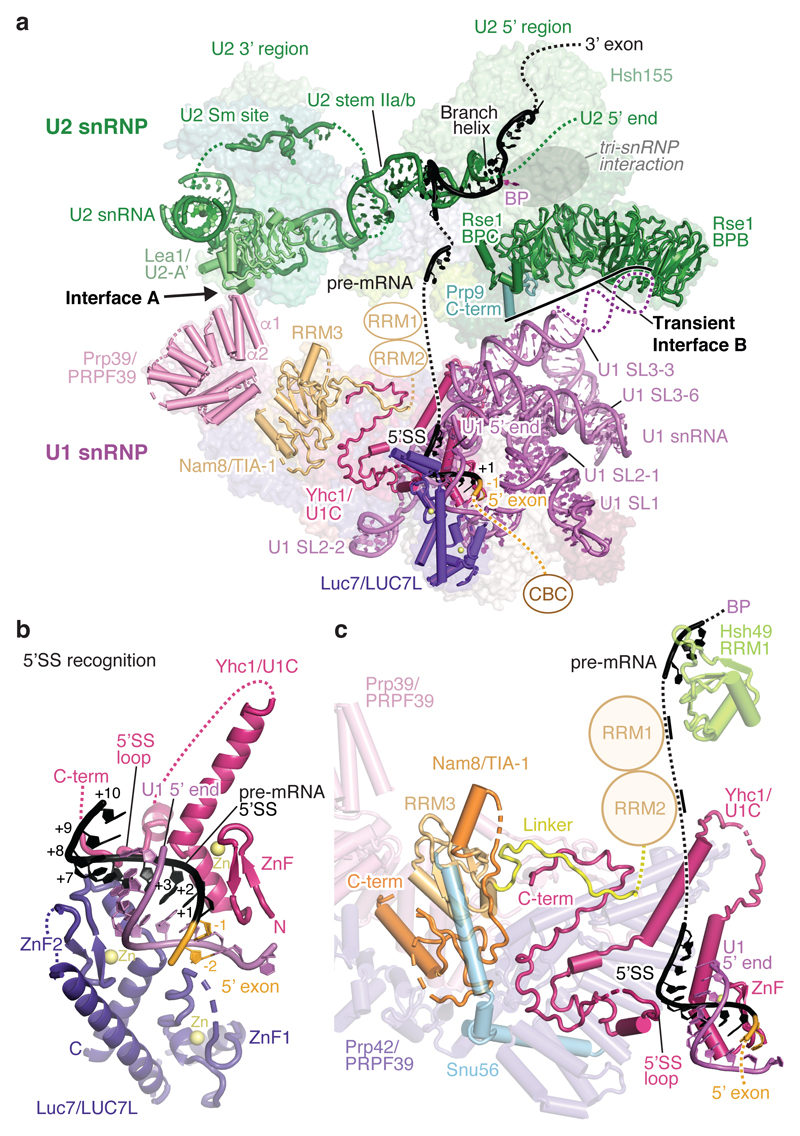

Figure 2. 5'SS recognition and implications for alternative splicing.

a. The A complex U1-U2 snRNP interfaces (A and B) and RNA network are shown as cartoons, and are superimposed on transparent surfaces of prespliceosome proteins. The U2 subunit Hsh155 surface (gray oval), which interacts with the tri-snRNP in the B complex, is freely accessible in the A complex. The U1 snRNP proteins Nam8 (orange, human TIA-1), Luc7 (purple, human LUC7-like, LUC7L) and Yhc1 (magenta, human U1C) are shown as ribbons. The remaining densities are likely accounted for by Nam8 (see c) and cap binding complex (CBC). Branch point, BP; β-propeller B and C, BPB and BPC; RNA-recognition motif, RRM. b. The pre-mRNA 5'SS is recognized by the U1 snRNA 5' end, and is stabilized by Luc7 and Yhc1. Notably, the Yhc1 ZnF and Luc7 ZnF2 domains are arranged with pseudo-C2 symmetry around the U1-5'SS helix. c. Nam8 binds the U1 snRNP through its linker (yellow), RNA recognition motif 3 (RRM3, light orange) and C-terminal regions (orange), while its RRM1 and RRM2 domains are mobile and project towards the intron, to bind uridine-rich sequences downstream of the pre-mRNA 5’SS (dashed line), like its human counterpart TIA-1 (ref. 18). Nam8 contacts the Yhc1 (human U1C) C-terminus, and human TIA-1 biochemically also interacts with human U1C18. Snu56 (blue), Prp39 (magenta), Prp42 (violet), and Hsh49 (light green) are shown as transparent ribbon models and other protein and U1 snRNA elements were removed for clarity.

The first 10 nucleotides of U1 snRNA are disordered in the free U1 snRNP12, but become ordered in our A complex structure by pairing with the pre-mRNA 5'SS (Fig. 2a,b). Additional density appeared adjacent to the U1–5'SS helix, into which we could build a newly ordered Yhc1 peptide (human U1C) that contacts the 5'SS phosphate backbone (+5 and +6 positions, the ‘Yhc1 5'SS loop’) and a near-complete model of Luc7 (Luc7 in ref. 12 was attributed to what is now assigned as Snu71) (Extended Data Figs 3a,c, 4a). While Luc7 is disordered in the free U1 snRNP, it associates stably with the U1–5'SS helix in the A complex (Extended Data Fig. 4a), suggesting a mechanism for the selection of weak 5'SS sequences13. In our structure Luc7 is anchored by its N-terminal α–helix 1 to the Sm ring subunit SmE, and its C3H-type Zn-finger 1 (ZnF1) domain binds where the 5' exon emerges from the U1–5'SS helix, in excellent agreement with RNA-protein crosslinks13 (Fig. 2b). The adjacent Luc7 C2H2-type ZnF2 contacts the U1–5'SS helix minor groove and the U1 snRNA phosphate backbone (nucleotides U5-C8). This interaction mirrors that between the Yhc1 ZnF domain and the 5'SS nucleotides +1 to +4 downstream of the 5'SS junction10 (Fig. 2b). Thus, Yhc1 and Luc7 make no base-specific interactions with the U1–5'SS helix, and instead cradle the U1–5'SS helix phosphate backbone to stabilize 5'SS binding. Consistent with the structure, weakening of any of these interactions can impair splicing and bypass the requirement for Prp28 helicase activity13–16.

The A complex structure reveals the first structural insights into the functions of the human alternative splicing factors LUC7-like (yeast Luc7) and TIA-1 (yeast Nam8) (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). Luc7 and its human homologues LUC7-like 1-3 are highly conserved, suggesting that the LUC7L N-terminal α-helix also anchors it to the SmE protein and that the invariant ZnF2 helix α8 similarly stabilizes the U1–5'SS helix to promote the inclusion of weak alternative splice sites13 (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Figs 3c, 6a). The yeast U1 snRNP subunit Nam8 and its human homologue TIA-1 contain three RNA recognition motif (RRM) domains and a C-terminal Gln-rich (Q-rich) extension (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Human TIA-1 binds to uridine-rich sequences downstream of the 5'SS predominantly through its RRM217,18 to allow the use of weak 5’SSs. The Nam8 RRM2 shows high sequence similarity to the TIA-1 RRM2, including the nearly identical RNP1 and RNP2 motifs, indicating that Nam8 binds uridine-rich sequences also through its RRM2 (Extended Data Fig. 6b). In the A complex structure the Nam8 RRM3 and its C-terminal region bind in a cavity of the Prp39-Prp42 heterodimer and contact the Yhc1 C-terminal region near the U1–5'SS helix (Fig. 2c). From this location, Nam8 could project its mobile RRM2 domain to bind uridine-rich intron sequences downstream of the 5'SS, consistent with crosslinking experiments17, and thereby promote meiotic pre-mRNA splicing19 (Fig. 2a,c).

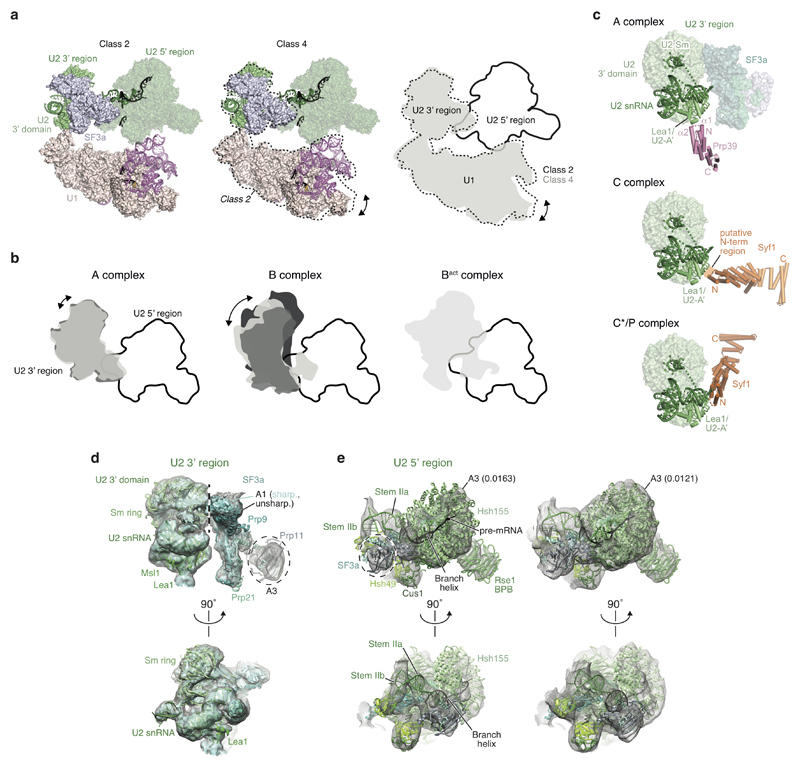

In the A complex, the U1 snRNP binds to the U2 snRNP through two interfaces, A and B (Fig. 2a). In interface A, the N-terminal helices α1-2 of the U1 protein Prp39 stably bind the U2 3' domain subunit Lea1 (human U2A') (Fig. 2a; Extended Data Fig. 5). The Prp39-Prp42 heterodimer binds Yhc1 to anchor the U2 snRNP 3' domain to the U1 snRNP. Similar interactions were observed biochemically between the human alternative splicing factor PRPF39 homodimer and U1C12 (yeast Yhc1), suggesting that PRPF39 may likewise contact the human U2 3' domain, though it is not an obligate component of the human A complex20 (Fig. 2a). Different, non-overlapping Lea1 surfaces are used to interact with the NTC protein Syf1 in the yeast C and C*/P complex conformations of the spliceosome21 (Extended Data Fig. 5c), suggesting that Lea1 aids in repositioning the U2 3' domain in multiple stages of splicing. Interface B is transient and found only in a subset of cryo-EM images (Extended Data Figs 2a, 5a,b). It involves weak interactions between the yeast-specific U1 snRNA Stem–loop (SL) 3-3 and the U2 SF3b Rse1 subunit β-propellers B and C (BPB, BPC) and the U2 SF3a Prp9 C-terminus. The pre-mRNA 5'SS and BP branching reactants are positioned ~150 Å apart in the A complex, with 40 nucleotides of the UBC4 intron looped out in-between (Fig. 2a, ED Fig. 1e,f). The surprisingly small interfaces between U1 and U2 snRNPs orient the snRNPs relative to each other, and this may facilitate 5'SS transfer in the assembled spliceosome and the subsequent dissociation of the U1 snRNP, consistent with structural and biochemical data7,8. While the precise U1–U2 snRNP interfaces may differ in the human A complex, a key function of U1–U2 (alternative) splicing factors could be to ensure that U1 and the U1–5’SS helix is oriented correctly relative to the U2 snRNP.

Prior to A complex formation, the yeast Msl5-Mud2 heterodimer recognizes the BP sequence through Msl5 and binds the U1 snRNP subunit Prp40 (human PRPF40) in the E complex, looping out the intron between the 5'SS and BP sequences22 (Extended Data Fig. 4e). While Prp40 was not identified in the free U1 snRNP12 or in our A complex structure, Prp40 crosslinks to Luc7 and Snu71 (ref. 12) and unassigned cryo-EM density in the A complex may indicate its peripheral location near Luc7 (Extended Data Figs 1e, 4a,e). Msl5-Mud2 may then be destabilized by the Sub2 helicase, allowing the Prp5 helicase to remodel U2 snRNA for the stable association of the U2 snRNP with the BP sequence in the A complex9. Prp5 was shown to physically interact with the U2 SF3b subunit Hsh155 HEAT repeats 1-6 and 9-12 (ref. 23) and with U2 snRNA at and surrounding the branchpoint-interacting stem–loop9. Thus, after Prp5 activity, Prp5 needs to dissociate to fully expose the Hsh155 HEAT repeats 11-13 together with the U2 snRNA 5' end in the A complex, to allow for the subsequent U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP association to assemble the spliceosome7–9 (Fig. 2a).

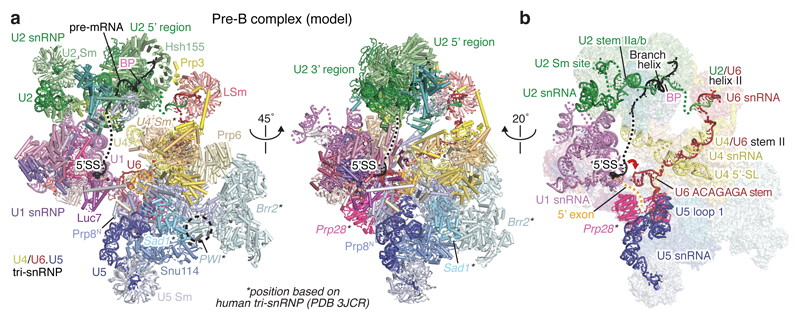

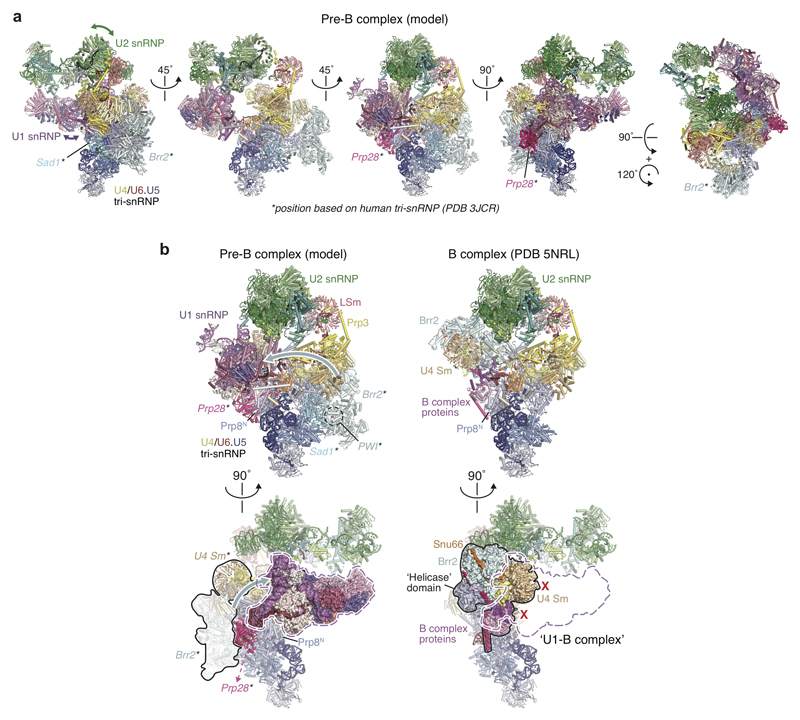

The A complex structure also provides new insights into formation of the fully assembled pre-B complex spliceosome, which requires integration of the tri-snRNP with the A complex. The subsequent Prp28 helicase-mediated transfer of the 5'SS from U1 to U6 snRNA and destabilization of the U1 snRNP produces the B complex spliceosome24. We first modelled a fully assembled yeast spliceosome, by superimposing the U2 snRNP SF3b-containing domains of the yeast A complex (this study) and the yeast B complex structure8. As in the B complex structure8, the U2 snRNP would associate with tri-snRNP via U2/U6 helix II and Prp3 (Extended Data Fig. 7). The modelling shows that the U1 snRNP would clash with large parts of the Brr2-containing ‘helicase’ domain (‘U1–B complex’; Extended Data Figs. 7b, 8b), which may be relieved owing to their known flexibilities8 (Extended Data Fig. 5a). However the known binding site for Prp28 at the U5 Prp8 N-terminal domain (Prp8N) observed in human tri-snRNP25 would be sterically occluded by the pre-bound B-complex proteins7,8,26. We therefore considered an alternative model for the assembled yeast ‘pre-B complex’ spliceosome, by combining the available data from yeast and human systems8,25,27,28 (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Figs. 7a, 8a). First, the isolated human25 and yeast tri-snRNP26,29 structures differ in their protein composition and conformation, indicating that different complexes accumulate at steady-state. In the human tri-snRNP structure25 the BRR2 helicase is held near SNU114 by the SAD1 protein and PRP28 is bound to the PRP8 N-terminal domain (PRP8N). In the yeast tri-snRNP26,29 and yeast and human B complex structures7,8 Brr2 is repositioned and loaded onto its U4 snRNA substrate and the B complex proteins replace Prp28 at the Prp8N domain, ready for spliceosome activation. Second, in humans, an ATPase-deficient PRP28 helicase stalls spliceosome assembly at the pre-B complex stage, prior to disruption of the U1–5'SS interaction28 and this complex comprises the U1 and U2 snRNPs, a loosely associated tri-snRNP, and SAD1 (ref. 28). Third, in yeast, Sad1 is essential for splicing and is very transiently associated with tri-snRNP27. Given the high conservation of the major spliceosome components in yeast and humans, the yeast spliceosome may likewise assemble with a human-like tri-snRNP that contains Prp28, Sad1, and a repositioned Brr2 helicase25,28. Based on these assumptions, we modelled a yeast pre-B complex spliceosome that comprises all five snRNPs with a combined molecular weight of ~3.1 megadalton and with only minor clashes (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). Notably, this model indicates that the U2 snRNP positions the U1 snRNP to deliver the U1–5'SS helix to the exposed U6 ACAGAGA stem in tri-snRNP, only ~20 Å away, where Prp28 is likely to mediate 5'SS transfer, consistent with protein-RNA crosslinks30 (Fig. 3b). This suggests that repositioning of the Brr2 helicase onto U4 snRNA would coincide with U1 snRNP release due to a steric clash, rendering Brr2 competent for spliceosome activation only after successful 5’SS transfer (see Extended Data Figs 7b and 8a for details). The model thus indicates a new molecular checkpoint to couple 5'SS transfer with U1 snRNP release and formation of the B complex (Extended Data Figs 7b and 8a).

Figure 3. Spliceosome assembly and 5'SS transfer.

a. One of the two alternative pre-B-complex models, suggesting that the U2 snRNP orients the U1 snRNP to deliver the pre-mRNA 5'SS to the U6 ACAGAGA stem. The model was obtained by superposing the yeast A (this study) and B complex structures (PDB 5NRL) and by modifying the locations of Brr2, U4 Sm ring, Sad1, and Prp28 to resemble a human-like pre-B complex conformation based on biochemical data and the human U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP structure (PDB 3JCR) (see Methods). Coloured as in Fig. 1 and ref. 8.

b. The pre-B complex RNA network and the Prp28 helicase are shown as cartoons and are superimposed on transparent surfaces of spliceosome proteins. Prp28 is positioned at the Prp8 N-terminal domain as in human tri-snRNP25 and may clamp onto the pre-mRNA near the U1–5'SS helix to destabilize it and transfer the 5'SS from U1 snRNA to the U6 snRNA ACAGAGA stem (red arrow), which are separated by ~20 Å in the pre-B model.

In summary, our prespliceosome structure reveals how the U1 and U2 snRNPs recognize the two reactants of the branching reaction and associate together with tri-snRNP into the fully assembled spliceosome. The results further suggest how the human alternative splicing factors LUC7-like and TIA-1 may influence splice site selection.

Methods

Prespliceosome preparation and purification

To obtain the prespliceosome A complexes for structural study, we prepared yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae containing a genomic TAPS affinity tag on the U2 snRNP subunit Hsh155, essentially as described31. Yeast were then grown in a 120 L fermenter, and splicing extract was prepared using the liquid nitrogen method, essentially as described32. Capped UBC4 pre-mRNA containing a point mutation (U to A) two nucleotides upstream of the branch point adenosine (BP) and three MS2 stem loops at the 3'-end was produced by in vitro transcription9,33. The RNA product was labelled with Cy5 at its 3’-end to monitor complex purification34. The pre-mRNA substrate was bound to MS2-MBP fusion protein and added to an in vitro splicing reaction carried out for 90 min at 23 ºC, essentially as described33. The reaction mixture was then centrifuged through a 40% glycerol cushion in buffer A (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.04% NP-40). The cushion was diluted with buffer A containing 1% glycerol, and applied to amylose resin (NEB) pre-washed with buffer B (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 75 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.03% NP-40). After 12 h incubation at 4 ºC, the resin was washed with buffer B and eluted in buffer B containing 50 mM KCl and 12 mM maltose. Fractions containing A complex were pooled and applied to Strep-Tactin resin (GE Healthcare), pre-washed with buffer B, and incubated for 4 h at 4 ºC. The resin was washed with buffer B containing 2 mM MgCl2, and eluted with buffer B containing 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM desthiobiotin, and 2 mM MgCl2. The A complex fractions were pooled and crosslinked using 1.1 mM BS3 (Sigma) on ice for 1 h, and subsequently quenched with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The sample was concentrated to ~0.4 mg mL-1 and immediately used for EM sample preparation. Mass spectrometry (not shown), indicated that homogenous A complex was purified, containing sub-stoichiometric amounts of Prp5 (Extended Data Fig. 1b). The splicing assay in Extended Data Fig. 1a was carried out as for A complex purification, but in a volume of 25 µL and in the absence of MS2-MBP fusion protein, and was visualized after 30 min of splicing at 23 ºC on a denaturing 14% polyacrylamide TBE gel with a Typhoon scanner (GE Healthcare).

Electron microscopy

For cryo-EM analysis the A complex sample was applied to R2/2 holey carbon grids (Quantifoil), precoated with a 5–7 nm homemade carbon film. Grids were glow-discharged for 20 s before deposition of 2.5 µL sample (~0.4 mg mL-1), and subsequently blotted for 2–3.5 s and vitrified by plunging into liquid ethane with a Vitrobot Mark III (FEI) operated at 4 °C and 100% humidity. Cryo-EM data was acquired on three separate FEI Titan Krios microscopes (datasets 1-3) operated in EFTEM mode at 300 keV, each equipped with a K2 Summit direct detector (Gatan) and a GIF Quantum energy filter (slit width of 20 eV, Gatan). Datasets 1 and 2 were recorded using ‘Krios 1’ and ‘Krios 2’ at the MRC-LMB, respectively, and dataset 3 using ‘Krios 2’ at the Astbury Biostructure Laboratory (University of Leeds). For dataset 1 5,935 movies were acquired using EPU (FEI) with a defocus range of –0.4 µm to –4.4 µm at a nominal magnification of 105,000x (1.13 Å pixel–1). The camera was operated in ‘counting’ mode with a total exposure time of 13 s fractionated into 20 frames, a dose rate of 4.25 e- pixel–1 s–1, and a total dose of 43 e- Å-2 per movie. Dataset 2 was collected in the same manner, except that 727 movies were recorded using SerialEM35, at a nominal magnification of 105,000x (1.14 Å pixel–1), a total exposure time of 8 s fractionated into 20 frames, a dose rate of 4.33 e- pixel–1 s–1 and a total dose of 27 e- Å-2 per movie. Dataset 3 was collected with EPU (FEI) similar to dataset 1, except that 2,745 movies were collected at a nominal magnification of 130,000x (1.07 Å pixel–1), a total exposure time of 8 s fractionated into 20 frames, a dose rate of 7.94 e- pixel–1 s–1 and a total dose of 56 e- Å-2 per movie.

Image processing

Movies were aligned using MOTIONCOR2 (ref. 36) with 5x5 patches and applying a theoretical dose-weighting model to individual frames. CTF parameters were estimated using Gctf37. Resolution is reported based on the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) (0.143 criterion) as described38 and B-factors were determined and applied automatically in RELION 2.1 (refs 39,40). Particles from dataset 1 were automatically picked using Gautomatch (Kai Zhang) and screened manually, and were then extracted in RELION with a 5602 pixel box size and pre-processed. Particles from datasets 2 and 3 were picked and pre-processed in the same way, and were then rescaled to the pixel size of dataset 1 (1.13 Å pixel–1) in RELION 2.1 by Fourier cropping during particle extraction with a 5602 pixel box. For rescaling, we first calculated 3D refinements in RELION 2.1 for each dataset (1-3) and performed real space correlation fits in UCSF Chimera to identify scaling factors for datasets 2 and 3 relative to dataset 1. Because the absolute magnification values differed slightly for the different microscopes, we re-determined the CTF values for datasets 2 and 3 using the new pixel sizes with Gctf37, and then re-extracted and rescaled the particles to the 5602 pixel box. Combining datasets 1-3 yielded a total dataset of 406,272 particles that were used for subsequent processing.

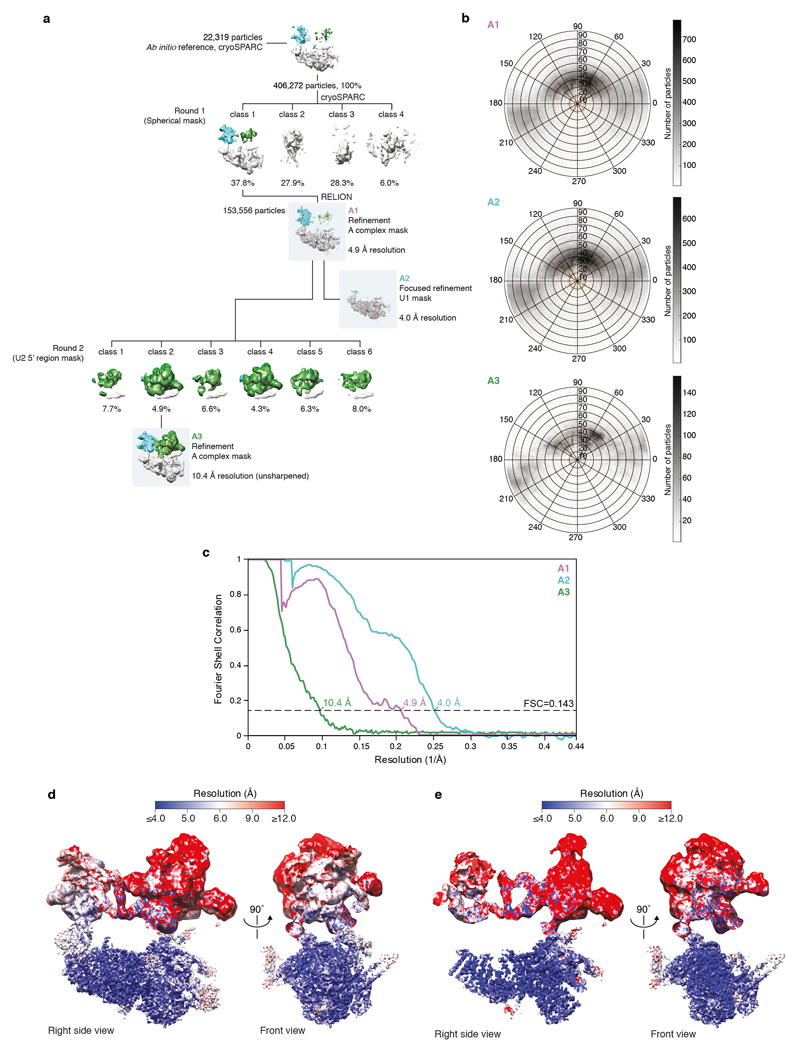

The first 22,319 particles from dataset 1 were used to generate an ab initio 3D reference for the A complex using default parameters and three classes in cryoSPARC41 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). The complete dataset (1-3) was subjected to a ‘heterogeneous’ (multi-reference) refinement in cryoSPARC using default parameters and four classes: the ab initio A complex reference and three ‘junk’ references (Extended Data Fig. 2a; Round 1). Class 1 contained 153,570 particles (37.8%, percentage of particles form the full dataset) and was used for a 3D refinement in RELION 2.1 with a soft mask in shape of the A complex. This yielded a density (map A1) with an overall resolution of 4.9 Å and a B-factor of -188 Å2, comprising U1 snRNP and the U2 snRNP 3’ region (Extended Data Figs 1e,d, 2, 9). To improve the U1 snRNP density, we prepared a soft mask enveloping the U1 snRNP with the volume eraser in UCSF Chimera42 and RELION 2.1 (refs 39,40). This allowed the focused refinement of the U1 snRNP (map A2) from the same 153,570 particles to an overall resolution of 4.0 Å resolution and a B-factor of -146 Å2 (Extended Data Figs 1e,d, 2, 9). In A complex the U2 snRNP 5' region is flexible relative the U1 and the U2 3' region (Extended Data Fig. 2). To position the U2 snRNP 5' region in the A complex, we used a soft mask surrounding the U2 5' region and carried out 3D classification without image alignment with six classes (Round 2, Extended Data Fig. 2a). This revealed a class with defined U2 5' region from 19,937 particles (4.9%) that could be refined to an overall resolution of 10.4 Å (Extended Data Figs 2, 9). Local resolution was estimated using ResMap43 (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e).

Structural Modeling

We prepared a composite model of the A complex by combining the A1-3 densities (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f). Model building was carried out in COOT44. The U1 snRNP coordinates were refined into the sharpened A2 density in PHENIX45 using the phenix.real_space_refine routine, and applying secondary structure, rotamer, nucleic acid, and metal ion restraints. Homology models for yeast Yhc1, Snp1, and Mud1 were generated using MODELLER46 from the human U1 snRNP crystal structures10 (PDB ID 4PJO, 4PKD) and were fitted and manually adjusted in the A2 map. The yeast B complex U5 Sm ring model was used as the initial model for the U1 Sm ring, and was manually adjusted in the A2 density. Initial models for Prp39 and Prp42 were generated by I-TASSER47 and were subsequently adjusted and extended manually. The Prp39 N-terminal residues 47-339 were modelled as poly-alanine due to a lower local resolution of ~5-6Å (Extended Data Figs 2d,e, 3c). Snu56, the Yhc1 C-terminus, the Snu71 N-terminus were modelled de novo, where Yhc1 residues 48-82 and 135-142 were modelled as poly-alanine. To build the Luc7 model a C3H-type ZnF (from PDB ID 1RGO) for ZnF1 and a C2H2-type ZnF (from Yhc1) for ZnF2 were used to guide modelling in the A2 density, with a local resolution of 4-5Å (Extended Data Fig. 3c). The helices connecting Luc7 ZnF1 and ZnF2 (α5-7) were modelled as poly-alanine, and assigned based on density connectivity. The U1 snRNP protein model is in excellent agreement with biochemical and protein crosslinking results12. The U1 snRNA model was generated based on similarity to U1 snRNA in the human U1 snRNP crystal structures (PDB ID 3CW1, 4PJO, 4PKD) and according to the yeast U1 snRNA secondary structure prediction48. All basepairing U1 snRNA regions (helix H, SL1, SL2-1, -2, SL3-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6), except for the SL3-7 and the tip of SL3-3, were modelled (Extended Data Fig. 3f,g). The human SL1 loop (PDB ID 4PKD) was rigid-body-fitted together with the homology model of the yeast Snp1 (described above), and the human U1 snRNA sequence was replaced with that from yeast. The loops connecting SL2-1 to SL2-2 as well as SL3-3 to SL3-4 and SL3-4 to SL3-5 and the tips of SL2-2, SL3-3, -4, and -5 were not built, due to a lower local resolution (~4.5Å). The location of a region of U1 snRNA SL3-7 was modelled as a phosphate backbone only and may correspond to the sequence surrounding residues 378-391 and 428-440. The U1 snRNA–pre-mRNA 5' splice site helix was modelled de novo, and the UBC4 pre-mRNA contained 12 nucleotides, ten from the intron (+1 to +10) and two from the 5' exon (–1 to –2).

The U2 snRNP 3' region (U2 3' domain and SF3a subcomplexes) from the yeast B complex structure (PDB ID 5NRL) were fitted into the A1 density using UCSF Chimera42, and the positions of Lea1, Msl1 and U2 snRNA residues 139-1169 were adjusted as a rigid body in COOT44. The U2 snRNP 5' region from the yeast B complex structure (PDB ID 5NRL) was fitted into the A3 density in UCSF Chimera. This provided an excellent fit, suggesting that the U2 5' region structure is not changed significantly from that observed in the yeast B complex8. To generate the complete A complex model, the refined U1 snRNP model and the U2 snRNP 3' region were fitted into the A3 density in UCSF Chimera, together with the fitted U2 snRNP 5' region. The final model comprises 34 proteins, U1 and U2 snRNAs, and the pre-mRNA substrate.

To generate the pre-B complex model we modified and combined structural models using COOT44, based on structural and biochemical data from yeast and human systems8,25,28. We first superimposed our A complex structure on the yeast B complex structure8 using the U2 SF3b-containing domain. The free human tri-snRNP structure (PDB ID 3JCR), which is likely to resemble the pre-B conformation7,25, was used to model the yeast tri-snRNP in the pre-B complex conformation. We first removed the B complex proteins from the yeast B complex structure, because they are absent in the purified human pre-B complex28. Human pre-B instead contained the PRP28 helicase and SAD1, and we therefore added crystal structures of the yeast Prp28 helicase49 (PDB ID 4W7S) and yeast Sad150 (PDB ID 4MSX) in their human tri-snRNP locations25. We then positioned the U4 Sm ring and Brr2 as in the human tri-snRNP structure, where the Brr2 PWI domain makes a conserved contact with Sad1 (ref. 51). We removed a Snu66 peptide bound to Brr2 from the model, since its binding at this site is uncertain in the pre-B complex conformation. Several minor differences remain between the free human tri-snRNP structure25 and the pre-B complex model, and these were not modelled. The final pre-B model contained only minor clashes, and one observed clash between the highly flexible Prp28 RecA-2 lobe25 and the flexible U6 snRNA 5' stem loop8,26 could be resolved by a minor repositioning of either domain. The final pre-B model comprises 66 proteins, five snRNAs, the pre-mRNA substrate, and has a combined molecular weight of ~3.1 MDa.

Figures were generated with PyMol (http://www.pymol.org) and UCSF Chimera.

Data availability

Three-dimensional cryo-EM density maps A1, A2, and A3 have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under the accession numbers EMD-4363, EMD-4364, and EMD-4365, respectively. The coordinate file of the A complex has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 6G90.

Extended Data

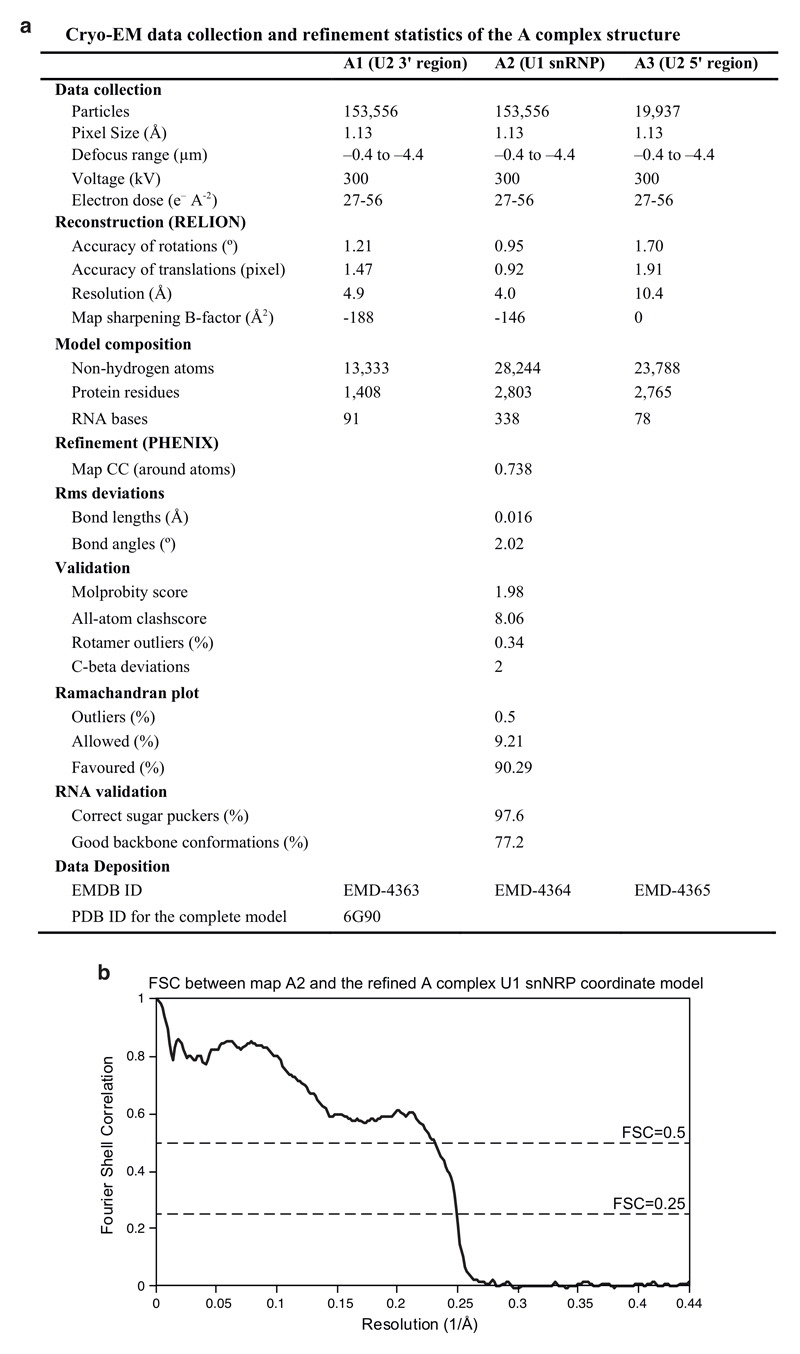

Extended Data Figure 1. Biochemical characterization and cryo-EM of the prespliceosome A complex.

a. Mutation of the UBC4 pre-mRNA branch point sequence (UACUAAC to UACAAAC, where A is the BP adenosine) stalls splicing before the first step, as described9. Splicing reactions were carried out for 30 min at 23 ºC in yeast extract using wild-type (lane 1) or mutant (U/A, lane 2) pre-mRNA (see Methods for details). This experiment was performed three times. The asterisk indicates a degradation product. For gel source data see Supplementary Fig. 1a. b. Protein analysis of purified A complex (SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie blue). The U2-associated Prp5 protein is sub-stoichiometric and not observed in the A complex structure. The purification and analysis of protein compositions were performed at least five times with similar results. For gel source data see Supplementary Fig. 1b. c. Cryo-EM micrograph of the A complex. Scale bar, 100 nm. d. 2D class averages of the A complex were determined in RELION 2.1 (refs 39,40), and reveal a bipartite architecture, comprising the U1 snRNP and the U2 snRNP 3' and 5' regions, respectively. e. Composite cryo-EM density of the A complex shown in two orthogonal views (compare Fig. 1). The respective densities used for modeling the U1 snRNP (A2, gray), the U2 3' region (A1, cyan), and the U2 5' region (A3, green) are coloured and superimposed on a transparent outline of the full A3 map (Methods). The overall resolution of each map as well as the percentage from the cleaned dataset of 153,556 particles are shown in parentheses. Non-modelled regions are indicated and putatively assigned. f. Composite cryo-EM density with the final A complex model superimposed in a cartoon representation. The path of 40 nucleotides of the disordered UBC4 pre-mRNA intron are indicated. A complex components are coloured as in Fig. 1. Views as in panel e.

Extended Data Figure 2. Cryo-EM image classification and refinement.

a. Image processing workflow for analysis of the A complex cryo-EM data set (Methods). To visualize differences between the reconstructions the U1 snRNP (gray), U2 3' (cyan) and U2 5' regions (green) are coloured. For each round of three-dimensional classification, the percentage of the data and the type of soft-edged mask are indicated. The type of mask and overall resolution are indicated for each 3D refinement (blue box). b. Orientation distribution plots for all particles that contribute to the respective A1, A2, and A3 cryo-EM reconstructions. c. Gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC = 0.143) of the respective A1, A2, and A3 cryo-EM reconstructions. d. Two views of the composite A complex cryo-EM density (maps A1, A2, and A3) coloured by local resolution as determined by ResMap43. e. As panel d, but for a central slice through the composite A complex cryo-EM map.

Extended Data Figure 3. Details of the U1 snRNP.

a. U1 snRNP structure with subunits coloured as in Fig. 1, except for Nam8 (orange), Snu56 (light blue), Snu71 (blue), Luc7 (dark purple), Mud1 (red) and U1 snRNA (various). The pre-mRNA nucleotides are labelled relative to the first nucleotide (+1) of the intron. The Nam8 RRM1 and RRM2 domains are flexible and project downstream of the 5'SS. The protein attributed to Luc7 in the free U1 snRNP structure12 was re-assigned to Snu71. Stem loop, SL; RNA recognition motif, RRM; Zn-finger, ZnF; N-terminus, N-term; C-terminus, C-term. In the structure we do not observe any evidence that the C-terminal tails of SmB, SmD1, and SmD3 interact with the 5’SS, consistent with their absence in the human 5’SS–minimal U1 snRNP crystal structure10. b. Representative regions of the sharpened U1 snRNP density determined at 4 Å resolution (map A2) are superimposed on the refined coordinate model. The density reveals side-chain details, and here segments from the Prp42 N-terminus (TPR repeat 1), the Sm ring subunit SmB, and the Snu56 α-helical domain are shown. c. The A2 cryo-EM density is shown superimposed on the coordinate models of a selection of U1 snRNP proteins: Luc7, Snu71, Yhc1, and Prp39. In the structure most of Snu71 is disordered, except for a small N-terminal domain (residues 2-43) that binds between the Prp42 N-terminus and the Snu56 KH-like fold, consistent with protein crosslinking12. Functional regions and disordered domains are indicated. d. The U1 snRNA–pre-mRNA 5' splice site (U1–5'SS) model is superimposed on its cryo-EM density (map A2). A secondary structure diagram of the U1–5'SS interaction is shown underneath the model. The register of the 5'SS is shifted by one nucleotide compared to the minimal human 5'SS–U1 snRNP crystal structure, due to an additional nucleotide in yeast U1 snRNA10 (U11). Lines indicate Watson–Crick base pairs and dots pseudouridine (ψ)-containing base pairs. e. The Prp39-Prp42 heterodimer is coloured to indicate each of their respective TPR repeats. f. Cryo-EM density of U1 snRNA from maps A2 (dark gray) and A3 (light gray) without (top) and with the superimposed coordinate model of yeast U1 snRNA (bottom). The model is labelled and coloured according to functional regions of U1 snRNA (5' end, pink; H helix, cyan; SL1, dark blue; SL2-1, green; SL3-1, light blue; SL2-2 and SL3-2 to -7, gray; 3’end and Sm site, yellow). Stem loop, SL. g. Secondary structure diagram of U1 snRNA. Bold letters indicate residues included in the model, lines indicate Watson–Crick base pairs, and dots G–U wobble and pseudouridine (ψ)-containing base pairs. Compare panel e. The conserved U1 snRNA ‘core’ is outlined with a gray box. The region of the putative phosphate backbone model of part of the U1 SL3-7 region is indicated with a gray box.

Extended Data Figure 4. Comparisons of yeast and human U1 snRNPs and implications for alternative splicing.

a. Formation of the U1–5'SS helix induces stable binding of Luc7. In the absence of a pre-mRNA 5'SS in the free U1 snRNP density (left, EMD-8622), Luc7 and the U1 5' end are disordered. Upon 5'SS recognition at the U1 5' end (center, map A2), Luc7 becomes ordered and stabilizes the U1–5'SS interaction, suggesting a mechanism for the selection of weak 5'SS sequences. The free U1 snRNP and the 5'SS-bound (map A2) cryo-EM densities are superimposed on the right. Although the long α-helical density next to Luc7 cannot be assigned with confidence, protein-protein crosslinking data12 and protein secondary structure prediction are consistent with either to Prp40 or Snu71. Based on additional biochemical data on the interaction between the α-helical Prp40 FF1 domain and Luc7 ZnF2 (ref. 52), we would speculate that the Prp40 FF1 domain is the most likely candidate for this density. b. Comparison of the yeast U1 snRNP ‘core’ with the human U1 snRNP crystal structure (PDB ID 3CW1). Protein and RNA (top) and RNA only (bottom) are shown side-by-side (left and center) and superimposed by a global alignment in PyMOL (right). Coloured as in Extended Data Fig. 3a. c. The yeast U1 snRNP model suggests regulatory mechanisms for human alternative splicing factors. The human homologues of the peripheral yeast U1 proteins may function through stabilization of the U1–5'SS interaction (region 1), of the U1-U2 3' region interface (region 2), or the U1-U2 5' interface (region 3). The yeast U1 snRNP ‘core’ is shown superimposed on a surface representation of the U1 snRNP model (top), compared with the similarly coloured human U1 snRNP (below). Interaction sites with the U2 snRNP are labelled (top). d. The location of yeast U1 snRNP components with homology to human splicing factors are indicated in the U1 snRNP structure. The Prp39-Prp42 heterodimer (human PRPF39 homodimer), Nam8 (ref. 18) (human TIA-1 and TIA-R), Luc7 (ref. 53) (human LUC7-like 1-3), and the Yhc1 C-terminus (human U1C) have clear counterparts in the human system. The yeast-specific U1 snRNA insertions may be replaced in the human system by alternative splicing factors that modulate interactions with the U2 5' region. e. Schematic model of the yeast E complex based on the U1 snRNP structure and biochemical data22. Luc7, Snu71, and Prp40 form a heterotrimer in vitro52, and their interacting regions may be located near unassigned density (compare Extended Data Fig. 1e) at the tip of an unassigned 40-residue α-helix next to Luc7 ZnF2. This helix is likely to belong to the U1 subunit Snu71 or Prp40, consistent with protein crosslinking12 and protein secondary structure prediction. Prp40 could then bind the yeast branch point binding protein (BBP, human SF1), which in turn interacts with Mud2 (human U2AF65) to tether the pre-mRNA branch point sequence in the E complex22.

Extended Data Figure 5. Conformational flexibility of the U2 snRNP.

a. Two defined positions of the U1 snRNP-U2 3' region could be identified relative to the U2 5' region. A complex models were fitted into class 2 and 4 from Round 2 of three-dimensional image classification (compare Extended Data Fig. 2a). The classes are aligned via their U2 5' region, illustrating their relative flexibility. b. Cartoon schematic of observed positions of the U2 3' region relative to the U2 5' region in A complex (left), B complex8 (center), and Bact complex (right, modelled from ref. 54). While in B complex the U2 3' region is free, in A and Bact complexes its position is influenced by interactions with Prp39 as well as Syf1 and Clf1, respectively. c. The U2 snRNP subunit Lea1 (human U2A’) aids to position the U2 snRNP 3' domain in different spliceosome states. In our A complex structure, the Prp39 TPR repeat T1 contacts the helical C-terminus of Lea1. In the yeast C complex structure, non-modeled density for the Syf1 N-terminus binds a neighboring but non-overlapping surface of Lea1 (PDB ID 5LJ5). In C*/P complex55 (PDB ID 6EXN), the Syf1 N-terminus binds yet another Lea1 surface and the U2 3' domain is repositioned relative to its C complex location. Together, this suggests that the Lea1 provides multiple interfaces that can be used to position the U2 3' domain in different spliceosomal complexes. d. Fit of the U2 3’ region coordinate model to the A1 cryo-EM density. The dashed black separates the U2 3’domain (Sm ring, Msl1 and Lea1 subunits, and U2 snRNA) and the SF3a subcomplex (Prp9, Prp11, and Prp21). Two orthogonal views are shown. See Supplementary Video 2. e. Fit of the U2 5’ region coordinate model to the A3 cryo-EM density. Density consistent with U2 snRNA stem IIa/b and the branch helix is observed. Two density thresholds are shown side-by-side (left, 0.0163; right, 0.0121), and orthogonal views are shown underneath. See Supplementary Video 2.

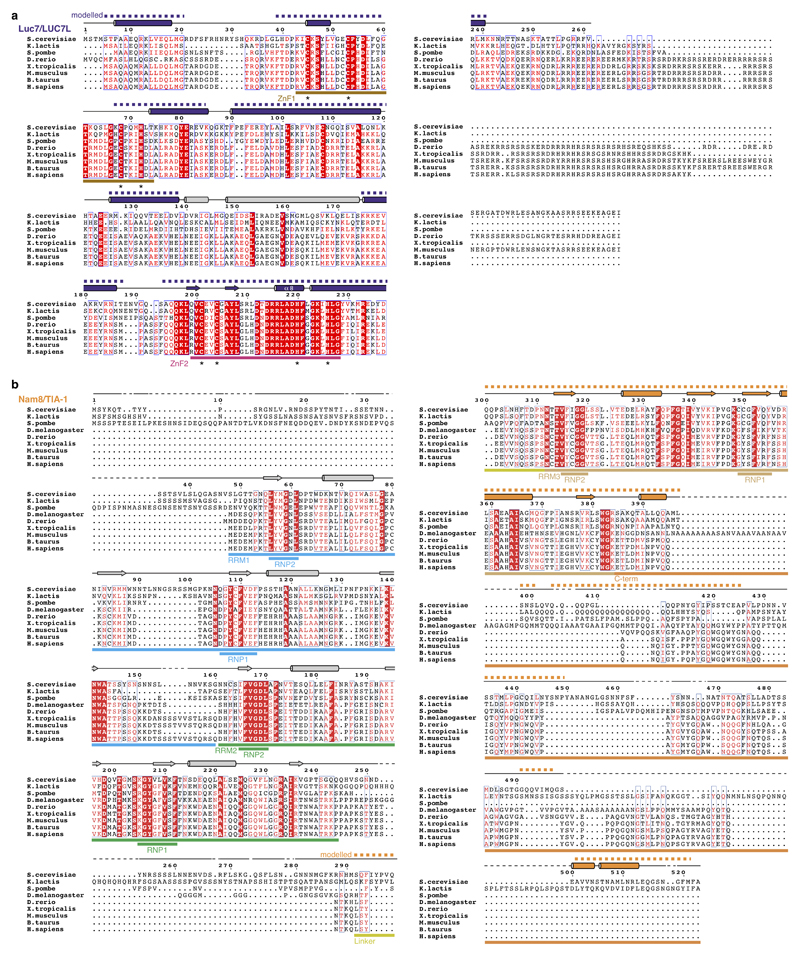

Extended Data Figure 6. Luc7 and Nam8 sequence alignments.

a. The Luc7 (human LUC7-like) amino acid sequence alignment comparing Saccharmoyces cerevisiae, Kluyveromyces lactis, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Danio rerio, Xenopus tropicalis, Mus musculus, Bos taurus, and Homo sapiens was generated with Clustal Omega and visualized with ESPript 3 (refs 56,57). For the human sequence, LUC7-like 1 was used. Secondary structure elements are indicated above the sequence and derive from the A complex structure (purple) or PSIPRED58 secondary structure prediction (gray). Modelled regions (dashed line) and the Zn-coordinating residues of Zn-finger 1 and 2 (ZnF, asterisk) are indicated. Invariant or conserved residues are highlighted with a red box or red letter font, respectively. b. As panel a but for Nam8 (human TIA-1) comparing Saccharmoyces cerevisiae, Kluyveromyces lactis, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Drosophila melanogaster, Danio rerio, Xenopus tropicalis, Mus musculus, Bos taurus, and Homo sapiens amino acid sequences. RNA recognition motif, RRM; ribonucleoprotein domain, RNP.

Extended Data Figure 7. Details of the pre-B complex model.

a. Multiple views of the pre-B complex model, generated by combining functional and structural data from yeast and human systems8,25. The mobility of the U1 snRNP relative to the U2 snRNP in A complex (this study) as well as of the U2 snRNP relative to tri-snRNP in the B complex structure8 are indicated (left). The pre-B model contained only minor clashes, and a clash between the highly flexible Prp28 C-terminal RecA-2 lobe (from human tri-snRNP25) and the highly flexible U6 snRNA 5' Stem loop (from yeast B complex8) may be resolved by small movements of either domain. See Methods for details on the pre-B model. b. Structural comparisons of the yeast pre-B model (this study) and the yeast B complex structure (PDB ID 5NRL, ref. 8) suggest the existence of a molecular checkpoint to couple 5'SS transfer to U1 snRNP release and formation of the activation-competent B complex. In the pre-B model (left) Sad1 tethers Brr2 through its interaction with the conserved Brr2 PWI domain51, and the U1 snRNP and its U1–5'SS helix are positioned near the U6 ACAGAGA region and the helicase Prp28. Subsequent to Prp28-mediated 5'SS transfer, Brr2 is repositioned onto its U4 snRNA substrate, guided by the B complex-specific proteins (right). In this conformation the Brr2 helicase and its associated factors would clash with the U1 snRNP, consistent with U1 snRNP destabilization and release yeast and human B complexes7,8. Brr2 is now ready to initiate spliceosome activation and formation of the active site in the Bact complex. Regions that are changed between pre-B and B complex models (black outline) and the clash between the Brr2-containing ‘helicase’ domain and the U1 snRNP in B complex (red ‘X’) are indicated. The lower right panel would conform to the alternative ‘U1-B complex’ model.

Extended Data Figure 8. Model for early splicing events.

a. Cartoon schematic of proposed early splicing events, detailing (I) assembly of pre-B complex spliceosome from A complex and the U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP and (II) the subsequent conversion to the pre-catalytic B complex spliceosome. In the pre-B model the mobile U1 snRNP is next to Prp28, which is bound at the Prp8N domain. To initiate 5'SS transfer, Prp28 could clamp the pre-mRNA at or next to the U1–5'SS helix to destabilize it and to hand over the 5'SS to the U6 ACAGAGA region of tri-snRNP, consistent with protein-RNA crosslinks30. Formation of the U6–5'SS interaction may induce the binding of the B complex proteins to replace Prp28 at the Prp8N domain and induce the large movement of Brr2 to its B complex location on U4 snRNA (Fig. 5). The U1 snRNP, now loosely tethered to U2, may dissociate from B complex due to the steric clash with the Brr2-containing ‘helicase’ domain8 (Extended Data Fig. 7b). In agreement with this, the human pre-B complex converts to a B complex-like state in presence of a 5'SS oligonucleotide, which coincides with U1 snRNP release28. This model can explain how Brr2 is kept inactive to prevent premature U4/U6 duplex unwinding26. The model thereby implies the existence of a molecular checkpoint, coupling 5'SS transfer from U1 to U6 snRNA with Brr2 helicase repositioning and U1 snRNP release to generate the activation-competent B complex spliceosome. b. Cartoon schematic of an alternative model for spliceosome assembly and 5'SS transfer that relies only on the yeast A complex (this work), tri-snRNP26,29, and B complex structures8. In this model the tri-snRNP that associates with A complex already contains the Brr2 helicase bound to the U4 snRNA substrate and the yeast B complex proteins at the Prp8 N-terminal (Prp8N) domain. The tri-snRNP then binds the A complex (transition I, ‘Assembly’), requiring a significant readjustment to avoid a steric clash of the Brr2-containing ‘helicase’ domain and the U1 snRNP (‘U1-B complex’). The Prp28 helicase is then recruited to U1 snRNP directly as the Prp28-binding site on the Prp8 N-terminal domain in human tri-snRNP is occupied by B complex proteins25. Prp28 then disrupts the U1-5'SS helix, leading to 5'SS transfer (transition II, ‘Transfer’). Similar to the ‘pre-B complex’ assembly model in panel a, the U1 snRNP, now freed from the 5'SS, may then be released due to a steric clash with the Brr2-containing ‘helicase’ domain. This model does not require Sad1. Compare to panel a.

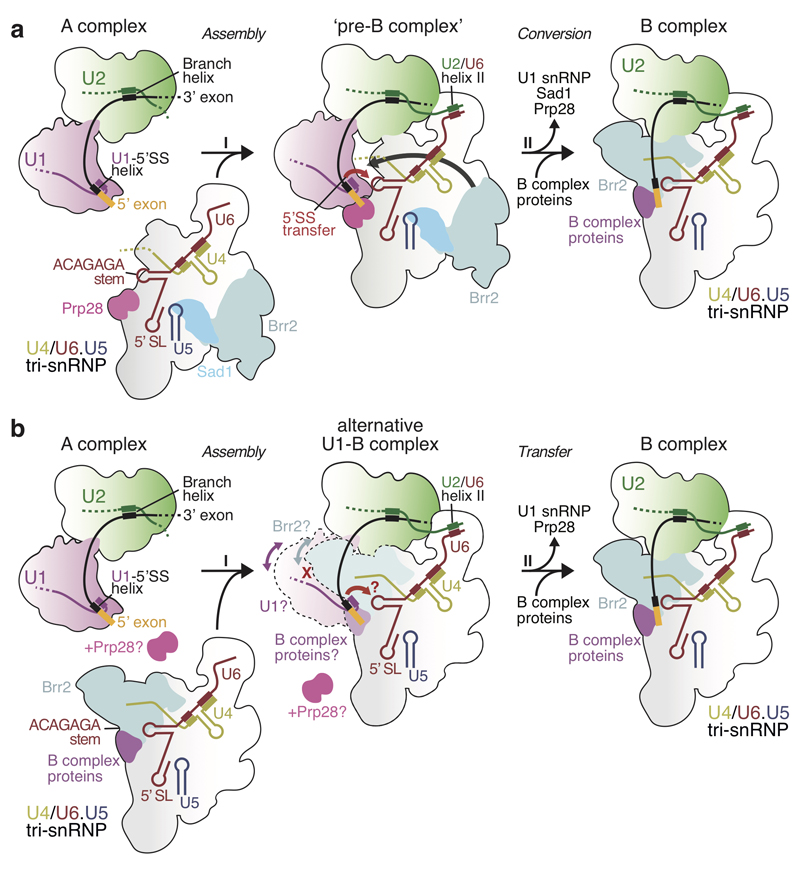

Extended Data Figure 9. Data collection, refinement statistics, and validation.

a. Cryo-EM data collection and refinement statistics of the A complex structure. Maps A1 and A3 were used to position the U2 snRNP 3' and 5' regions, respectively (see Methods). b. FSC between the A2 cryo-EM density and the refined A complex U1 snRNP coordinate model.

Extended Data Table 1. Summary of the components modelled into the A complex cryo-EM densities.

| Proteins and RNA included in the model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-complexes | Protein/RNA | Total residues | M.W. (kDa) | Modelled residues | Modelling template (PDB ID) | Modelling | Chain ID | Human name |

| U1 snRNP | Mud1 | 298 | 34.4 | 17-42; 62-81; 84-94 97-123; 134-148 | 4PKD | Docked | A | U1A |

| Snp1 | 300 | 34.4 | 5-55; 58-88; 94-204 | 4PJO, 4PKD | Docked and rebuilt | B | U1-70K | |

| Yhc1 | 231 | 27.0 | 2-59; 67-142; 153-195 | 4PJO, 4PKD | Docked, rebuilt, de novo | C | U1C | |

| Prp39 | 629 | 74.8 | 47-63; 66-85; 88-102; 108-119 124-136; 139-154; 160-172; 177-190; 193-208; 217-236; 250-266; 271-275; 276-286; 289-304; 307-321; 325-382; 388-553; 561 -626 | de novo | D | PRPF39 | ||

| Prp42 | 544 | 65.1 | 2-542 | de novo | E | PRPF39 | ||

| Nam8 | 523 | 57.0 | 292-400; 404-425; 434-449 491-497; 501-521 | de novo | F | TIA-1 | ||

| Snu56 | 492 | 56.5 | 45-104; 109-170; 185-294 | de novo | G | |||

| Luc7 | 261 | 30.2 | 5-20; 39-59; 67-84; 91-120 126-138; 175-187; 195-241 | de novo | H | LUC7L | ||

| Snu71 | 620 | 71.4 | 2-43 | de novo | J | RBM25 | ||

| SmB | 196 | 22.4 | 2-63; 73-131 | 5NRL | Docked and adjusted | b | SmB | |

| SmD3 | 101 | 11.2 | 3-95 | 5NRL | Docked and adjusted | d | SmD3 | |

| SmD1 | 146 | 16.3 | 1-73; 78-119 | 5NRL | Docked and adjusted | h | SmD1 | |

| SmD2 | 110 | 12.9 | 8-108 | 5NRL | Docked and adjusted | i | SmD2 | |

| SmE | 96 | 9.7 | 8-63; 73-93 | 5NRL | Docked and adjusted | e | SmE | |

| SmF | 86 | 10.4 | 12-84 | 5NRL | Docked and adjusted | f | SmF | |

| SmG | 77 | 8.5 | 2-77 | 5NRL | Docked and adjusted | g | SmG | |

| U1 snRNA | 568 | 182.3 | 1-61; 67-95; 103-112; 115-144; 152-173; 181-202; 236-258; 260-264; 270-275; 280-287; 295-325; 378-394; 424-440; 516-532; 538-564 | 4PJO, 4PKD | Docked and de novo | 1 | ||

| Unknown | 1-56 | de novo | X | |||||

| U2 snRNP | Msl1 | 111 | 12.8 | 28-111 | 5NRL | Docked | Y | U2-B" |

| Leal | 238 | 27.2 | 1-170 | 5NRL | Docked | W | U2-A' | |

| SmB | 196 | 22.4 | 12-54; 76-102 | 5NRL | Docked | s | SmB | |

| SmD3 | 101 | 11.2 | 4-85 | 5NRL | Docked | v | SmD3 | |

| SmD1 | 146 | 16.3 | 1-48; 78-101 | 5NRL | Docked | t | SmD1 | |

| SmD2 | 110 | 12.9 | 17-108 | 5NRL | Docked | u | SmD2 | |

| SmE | 96 | 9.7 | 10-63; 71-93 | 5NRL | Docked | w | SmE | |

| SmF | 86 | 10.4 | 12-84 | 5NRL | Docked | x | SmF | |

| SmG | 77 | 8.5 | 2-76 | 5NRL | Docked | y | SmG | |

| Hsh155 | 971 | 110.0 | 132-149; 157-971 | 5NRL | Docked | O | SF3B1 | |

| Rse1 | 1361 | 153.8 | 53-305; 323-571; 581-784; 814-890; 918-1265; 1292-1361 | 5NRL | Docked | P | SF3B3 | |

| Cus1 | 436 | 50.3 | 125-213; 239-353; 361-376 | 5NRL | Docked | Q | SF3B2 | |

| Hsh49 | 213 | 24.5 | 9-86; 106-144; 147-185; 189-203 | 5NRL | Docked | R | SF3B4 | |

| Rds3 | 107 | 12.3 | 2-104 | 5NRL | Docked | S | SF3B14b | |

| Ysf3 | 85 | 10.0 | 2-84 | 5NRL | Docked | z | SF3B5 | |

| Prp9 | 530 | 63.0 | 1-97; 112-378; 407-478; 503-528 | 5NRL | Docked | T | SF3A3 | |

| Prp11 | 266 | 29.9 | 34-47; 51-105; 115-136; 149-253 | 5NRL | Docked | U | SF3A2 | |

| Prp21 | 280 | 33.1 | 89-206; 220-228 | 5NRL | Docked | V | SF3A1 | |

| U2 snRNA | 1175 | 363.8 | 3-13; 30-73; 79-86; 108-122; 139-150; 1089-1109; 1115-1130; 1138-1154; 1159-1169 | 5NRL | Docked | 2 | ||

| UBC4 U/A pre-mRNA | 135 | 40.6 | -1-10; 51-53; 57-79 | 5NRL, 4PJO | Docked and rebuilt | I | ||

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information containing original gel data (Supplementary Fig. 1), two supplementary videos (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2) and a PyMol session of the A complex coloured as in Fig. 1 (PDB coordinate file: 6G90) are available in the online version of the paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Savva, S. Chen, G. Cannone, G. McMullan, J. Grimmett and T. Darling for maintaining electron microscopy and computing facilities; the mass spectrometry facility for protein identification; A. Murzin for discussions; E. Hesketh for assistance with cryo-EM data collection and S.-C. Cheng, A. Newman, L. Strittmatter, M. E. Wilkinson for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank J. Löwe, V. Ramakrishnan, D. Barford and R. Henderson for their continuing support. The project was supported by the Medical Research Council (MC_U105184330) and European Research Council Advanced Grant (693087-SPLICE3D). C.P. was supported by an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship (984-2015).

Footnotes

Author contributions

C.P. and P.-C.L. established complex preparation, performed cryo-EM data analysis, model building, and refinement. C.C. assisted with cryo-EM analysis. C.P., P.-C.L. and K.N. analyzed the structure and wrote the manuscript. C.P. and P.-C.L. designed the project and K.N. supervised the project.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author information

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Will CL, Lührmann R. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003707. a003707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papasaikas P, Valcarcel J. The spliceosome: The ultimate RNA chaperone and sculptor. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson ME, Lin PC, Plaschka C, Nagai K. Cryo-EM Studies of Pre-mRNA Splicing: From Sample Preparation to Model Visualization. Annu Rev Biophys. 2018 doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070317-033410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behzadnia N, et al. Composition and three-dimensional EM structure of double affinity-purified, human prespliceosomal A complexes. EMBO J. 2007;26:1737–1748. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao G, Dudley SC., Jr RBM25/LUC7L3 function in cardiac sodium channel splicing regulation of human heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2013;23:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hackman P, et al. Welander distal myopathy is caused by a mutation in the RNA-binding protein TIA1. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:500–509. doi: 10.1002/ana.23831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertram K, et al. Cryo-EM structure of a pre-catalytic human spliceosome primed for activation. Cell. 2017;170:701–713 e711. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plaschka C, Lin PC, Nagai K. Structure of a pre-catalytic spliceosome. Nature. 2017;546:617–621. doi: 10.1038/nature22799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang WW, Cheng SC. A novel mechanism for Prp5 function in prespliceosome formation and proofreading the branch site sequence. Genes Dev. 2015;29:81–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.253708.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo Y, Oubridge C, van Roon AM, Nagai K. Crystal structure of human U1 snRNP, a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle, reveals the mechanism of 5' splice site recognition. Elife. 2015;4:e04986. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neubauer G, et al. Identification of the proteins of the yeast U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex by mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:385–390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, et al. CryoEM structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae U1 snRNP offers insight into alternative splicing. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1035. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01241-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puig O, Bragado-Nilsson E, Koski T, Seraphin B. The U1 snRNP-associated factor Luc7p affects 5' splice site selection in yeast and human. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5874–5885. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal R, Schwer B, Shuman S. Structure-function analysis and genetic interactions of the Luc7 subunit of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae U1 snRNP. RNA. 2016;22:1302–1310. doi: 10.1261/rna.056911.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwer B, Shuman S. Structure-function analysis of the Yhc1 subunit of yeast U1 snRNP and genetic interactions of Yhc1 with Mud2, Nam8, Mud1, Tgs1, U1 snRNA, SmD3 and Prp28. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:4697–4711. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen JY, et al. Specific alterations of U1-C protein or U1 small nuclear RNA can eliminate the requirement of Prp28p, an essential DEAD box splicing factor. Mol Cell. 2001;7:227–232. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puig O, Gottschalk A, Fabrizio P, Seraphin B. Interaction of the U1 snRNP with nonconserved intronic sequences affects 5' splice site selection. Genes Dev. 1999;13:569–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Förch P, Puig O, Martinez C, Seraphin B, Valcarcel J. The splicing regulator TIA-1 interacts with U1-C to promote U1 snRNP recruitment to 5' splice sites. EMBO J. 2002;21:6882–6892. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spingola M, Ares M., Jr A yeast intronic splicing enhancer and Nam8p are required for Mer1p-activated splicing. Mol Cell. 2000;6:329–338. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agafonov DE, et al. ATPgammaS stalls splicing after B complex formation but prior to spliceosome activation. RNA. 2016;22:1329–1337. doi: 10.1261/rna.057810.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fica SM, Nagai K. Cryo-electron microscopy snapshots of the spliceosome: structural insights into a dynamic ribonucleoprotein machine. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24:791–799. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abovich N, Rosbash M. Cross-intron bridging interactions in the yeast commitment complex are conserved in mammals. Cell. 1997;89:403–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang Q, et al. SF3B1/Hsh155 HEAT motif mutations affect interaction with the spliceosomal ATPase Prp5, resulting in altered branch site selectivity in pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev. 2016;30:2710–2723. doi: 10.1101/gad.291872.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staley JP, Guthrie C. An RNA switch at the 5' splice site requires ATP and the DEAD box protein Prp28p. Mol Cell. 1999;3:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agafonov DE, et al. Molecular architecture of the human U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP. Science. 2016;351:1416. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen THD, et al. CryoEM structure of the yeast U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP at 3.7 Å resolution. Nature. 2016;530:298–302. doi: 10.1038/nature16940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang YH, Chung CS, Kao DI, Kao TC, Cheng SC. Sad1 counteracts Brr2-mediated dissociation of U4/U6.U5 in tri-snRNP homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:210–220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00837-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boesler C, et al. A spliceosome intermediate with loosely associated tri-snRNP accumulates in the absence of Prp28 ATPase activity. Nature Communications. 2016;7:11997. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wan R, et al. The 3.8 A structure of the U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP: Insights into spliceosome assembly and catalysis. Science. 2016;351:466–475. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ismaili N, Sha M, Gustafson EH, Konarska MM. The 100-kda U5 snRNP protein (hPrp28p) contacts the 5' splice site through its ATPase site. RNA. 2001;7:182–193. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201001807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen THD, et al. The architecture of the spliceosomal U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP. Nature. 2015;523:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature14548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umen JG, Guthrie C. A novel role for a U5 snRNP protein in 3' splice site selection. Genes Dev. 1995;9:855–868. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galej WP, et al. CryoEM structure of the spliceosome immediately after branching. Nature. 2016;537:197–201. doi: 10.1038/nature19316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Ach RA, Curry B. Direct and sensitive miRNA profiling from low-input total RNA. RNA. 2007;13:151–159. doi: 10.1261/rna.234507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng SQ, et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang K. Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J Struct Biol. 2016;193:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheres SHW, Chen S. Prevention of overfitting in cryo-EM structure determination. Nature methods. 2012;9:853–854. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimanius D, Forsberg BO, Scheres SH, Lindahl E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. Elife. 2016;5:e18722. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, Tagare HD. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat Methods. 2014;11:63–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Webb B, Sali A. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2014. Ch. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J, et al. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12:7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kretzner L, Krol A, Rosbash M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae U1 small nuclear RNA secondary structure contains both universal and yeast-specific domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:851–855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacewicz A, Schwer B, Smith P, Shuman S. Crystal structure, mutational analysis and RNA-dependent ATPase activity of the yeast DEAD-box pre-mRNA splicing factor Prp28. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:12885–12898. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hadjivassiliou H, Rosenberg OS, Guthrie C. The crystal structure of S. cerevisiae Sad1, a catalytically inactive deubiquitinase that is broadly required for pre-mRNA splicing. RNA. 2014;20:656–669. doi: 10.1261/rna.042838.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Absmeier E, Santos KF, Wahl MC. Functions and regulation of the Brr2 RNA helicase during splicing. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:3362–3377. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1249549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ester C, Uetz P. The FF domains of yeast U1 snRNP protein Prp40 mediate interactions with Luc7 and Snu71. BMC Biochem. 2008;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kimura E, et al. Serine-arginine-rich nuclear protein Luc7l regulates myogenesis in mice. Gene. 2004;341:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan C, Wan R, Bai R, Huang G, Shi Y. Structure of a yeast activated spliceosome at 3.5 A resolution. Science. 2016;353:904–911. doi: 10.1126/science.aag0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilkinson ME, et al. Postcatalytic spliceosome structure reveals mechanism of 3'-splice site selection. Science. 2017;358:1283–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robert X, Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W320–324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sievers F, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W349–357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Three-dimensional cryo-EM density maps A1, A2, and A3 have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under the accession numbers EMD-4363, EMD-4364, and EMD-4365, respectively. The coordinate file of the A complex has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 6G90.