Abstract

In addition to muscle weakness, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is associated with an increased incidence of skeletal fractures. The SOD1G93A mouse model recapitulates many features of human ALS. These mice also exhibit decreased bone mass. However, the functional, or biomechanical, behavior of the skeleton in SOD1G93A mice has not been investigated. To do so, we examined skeletal phenotypes in end-stage (16-week-old) SOD1G93A female mice and healthy littermate female controls (N=9–10/group). Outcomes included trabecular and cortical bone microarchitecture by microcomputed tomography; stiffness and strength via three-point bending; resistance to crack growth by fracture toughness testing; and cortical bone matrix properties via cyclic reference point indentation.

SOD1G93A mice had similar bone size, but significantly lower trabecular bone mass (−54%), thinner trabeculae (−41%) and decreased cortical bone thickness (−17%) and cortical area (−18%) compared to control mice (all p<0.01). In line with these bone mass and microstructure deficits, SOD1G93A mice had significantly lower femoral bending stiffness (−27%) and failure moment (−41%), along with decreased fracture toughness (−18%) (all p<0.001).

This is the first study to demonstrate functional deficits in the skeleton of end-stage ALS mice, and imply multiple mechanisms for increased skeletal fragility and fracture risk in patients in ALS. Importantly, our results provide strong rationale for interventions to reduce fracture risk in ALS patients with advanced disease.

Keywords: ALS mouse model, bone strength, bone biomechanics, fracture toughness, microCT

Introduction

In addition to severe skeletal muscle deterioration, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) has recently been linked to increased incidences of skeletal fractures, as well as elevated serum bone turnover markers in ALS patients (1, 2). These patients exhibit decreased bone mineral density, which is associated with increased fracture risks (3, 4). It is postulated that reduced mechanical load from skeletal muscle atrophy contributes to bone loss, but the exact alterations in bone functional, or biomechanical, properties are still unclear.

The ALS SOD1G93A mouse model has recently been shown to have reduced trabecular and cortical bone mass (5). This bone loss was due to reduced bone formation and increased bone resorption in 16-week-old SOD1G93A mice. While this prior study characterized alterations in molecular, cellular, and structural properties of skeleton in the ALS mouse model, the impact of the SOD1G93A mutation on functional properties of the skeleton is still unknown. By assessing the biomechanical properties of long bones from these mice, we can infer alterations in the functional properties of bone as a consequence of ALS.

Thus, we examined bone mass, microarchitecture, and biomechanics in ALS SOD1G93A mice. We hypothesized that bone microstructure and biomechanical outcomes, such as the bending stiffness and moments and fracture toughness, will be lower in ALS SOD1G93A mice compared to their littermate controls.

Materials and Methods

Animals:

We used 16-week-old ALS SOD1G93A female mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and their sex- and age-matched littermate controls (n = 9–10/group) for this study. These same animals had been previously demonstrated to exhibit decline in electrophysiological and functional parameters in the skeletal muscle (6). Mice were housed 3–5 per cage, maintained on a 12/12 hour light/dark cycle, had ad libitum access to standard laboratory rodent chow and water, and were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation at the end of the experiment. All animal procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Specimen harvesting and preparation:

After being cleaned of its soft tissue, the left femur was wrapped in saline-soaked gauze and stored at −20 °C until imaging by microcomputed tomography (microCT) and mechanical testing by unnotched three point bending. The right femur was wrapped in saline soaked gauze and stored at −20 °C until fracture toughness testing. The right tibia was stored similarly until cyclic reference point indentation testing.

Mechanical testing:

The left frozen femurs were thawed and subjected to three-point bending (Bose ElectroForce 3200 with 150 N load cell, Bose Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN). To determine the bending stiffness (N•mm2), maximum moment (N•mm), and failure moment (N•mm), femur was loaded to failure on the posterior surface at a constant displacement rate of 0.03 mm/sec with the two lower support points spaced 8 mm apart. Force-displacement data were acquired at 30 Hz. Estimated elastic modulus (Effective modulus, MPa) was calculated by using the moment of inertia derived from microCT scans (7).

To assess the effects of ALS on resistance to fracture in the skeleton, the right frozen femurs were thawed and subjected to fracture toughness testing (8). A through-wall notch was first created on the anterior surface of the femur using a low-speed saw and polished with a razor blade. After microCT characterization of the notch dimensions, femurs were subjected to three-point bending (Bose ElectroForce 3200 with 150 N load cell; Bose Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) with a span length of 8 mm and preload at −0.4 N and a constant displacement rate of 0.001 mm/s to failure. Force-displacement data and the critical stress intensity factor (Kc; fracture toughness) were analyzed and calculated by MatLab R2011b (MathWorks, Natick, MA):

where Pc is the maximum load, S is the span length, Ro and Ri are the mean outer and inner radii of the femoral cortex, Rm is the average of Ro and Ri, θc is the initial crack angle, and Fb is the geometry factor. Ro, Ri, and θc were determined from microCT images of the notched femurs.

In addition to assessing the whole bone mechanical properties, we assessed cortical bone matrix properties by cyclic reference point indentation (Biodent 1000; Active Life Scientific, Santa Barbara, CA) (9). The system was equipped with a 90° conical, 2.5 μm radius tip test probe. Indentation tests were conducted at a maximum force of 2 N at 2 Hz for 10 cycles. Three indentation measurements of 10 cycles each were taken at the distal end of the tibia diaphysis in the medial quadrant, a minimum of 500 μm apart, and averaged per specimen. Outcomes included total indentation distance (TID, μm), indentation distance increase (increase in indentation distance of the last cycle relative to the first cycle, IDI, μm), and creep indentation distance (CID, μm) (10).

Bone microarchitecture:

Micro-computed tomographic (µCT) imaging was performed on the distal metaphysis and mid-diaphysis of the femur using a high-resolution desktop imaging system (µCT40, Scanco Medical AG, Brüttisellen, Switzerland) in accordance with the ASBMR guidelines for the use of µCT in rodents (11). Scans were acquired using a 10 µm3 isotropic voxel size, 70 kVp and 114 mA peak x-ray tube potential and intensity, 200 ms integration time, and were subjected to Gaussian filtration. We determined femoral length by measuring the distance from the femoral head to the distal end of femoral condyles on µCT scans. The distal metaphyseal region that we analyzed began 200 µm (20 slices) proximal to the distal growth plate and extended proximally 1.3 mm (130 slices). Cortical bone morphology was evaluated in the femoral mid-diaphysis in a region that started 55% of the bone length below the femoral head and extended 500 µm (50 slices) distally. Thresholds of 456 and 700 mg HA/cm3 were used for evaluation of trabecular and cortical bone, respectively. Trabecular bone outcomes included trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV, %), thickness (Tb.Th, µm), number (Tb.N, μm−1) and separation (Tb.Sp, µm). Cortical bone outcomes included cortical tissue mineral density (TMD, mg HA/mm3), cortical thickness (Ct.Th, µm), total cross-sectional and cortical bone areas (mm2), cortical bone area fraction (Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar, %), and the maximum and minimum moments of inertia (Imax and Imin , mm4).

Statistical analysis:

All data were checked for normality, and standard descriptive statistics were computed. Two-tailed student t-test was used to test for differences between groups. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05. Data are reported as mean ± SEM, unless noted.

Results

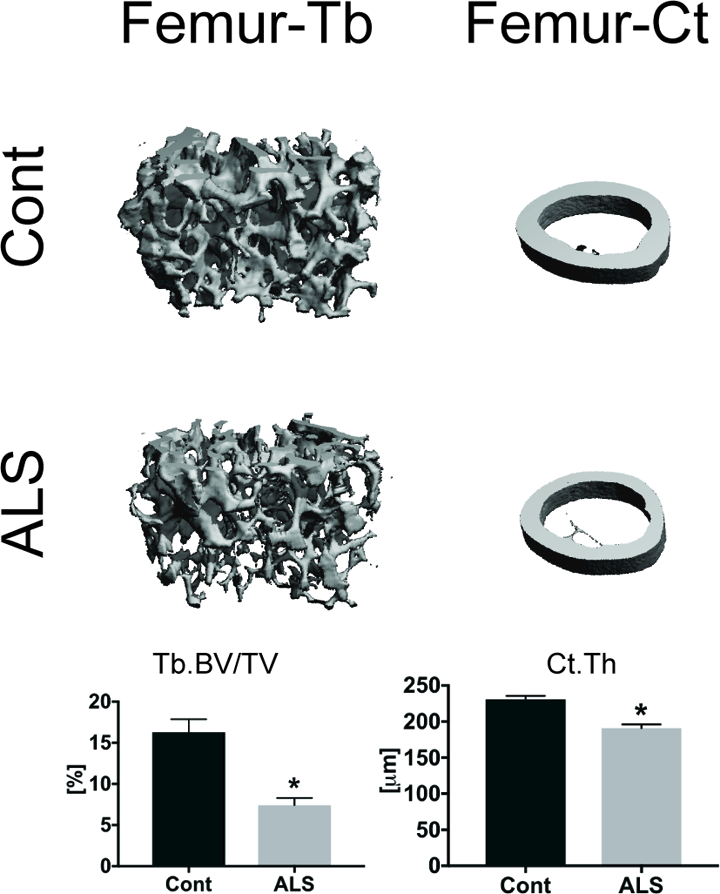

Both trabecular and cortical bone mass and microarchitecture were deficient in the SOD1G93A mice compared to controls (Table 1). In particular, trabecular BV/TV was 54% lower in ALS mice than controls (p = 0.0002, Fig 1), largely attributable to a decrease in trabecular thickness (−41%, p<0.001). Trabecular separation and number did not differ between ALS SOD1G93A mice and their littermate controls. Femoral cortical bone thickness and area were lower by 17% (p < 0.0001) and 18% (p = 0.0002), respectively, in ALS mice compared to their littermate controls (Figure 1, Table 1). While the total bone area and cortical bone area fraction did not differ, cortical tissue mineral density was 3% lower in ALS SOD1G93A mice (p < 0.0001). The maximum area moment of inertia was 21% lower (p = 0.002) in ALS SOD1G93A mice.

Table 1:

Femoral trabecular and cortical bone microarchitecture, assessed by µCT (mean ± SEM).

| Cont | ALS | % Difference ALS vs. Cont |

p-value ALS vs. Cont |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trabecular | Tb.Th [μm] | 68.7±1.4 | 40.6±1.4 | −40.8 | <0.0001 | |

| Tb.Sp [μm] | 280±14 | 287±13 | −2.3 | 0.75 | ||

| Tb.N [1/μm] | 3.55±0.16 | 3.49±0.13 | −1.7 | 0.77 | ||

| Cortical | Total Area [mm2] | 1.97±0.06 | 1.87±0.03 | −4.7 | 0.17 | |

| Bone Area [mm2] | 1.04±0.03 | 0.86±0.02 | −17.7 | 0.0002 | ||

| Area Fraction [%] | 40.9±7.7 | 36.8±6.1 | −9.8 | 0.68 | ||

| TMD [mg HA/cm3] | 1260±4.2 | 1220±4.6 | −2.7 | <0.0001 | ||

| Imax [mm4] | 0.36±0.02 | 0.28±0.01 | −21.0 | 0.002 | ||

| Imin [mm4] | 0.16±0.01 | 0.14±0.01 | −15.6 | 0.067 | ||

Abbreviations: trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), trabecular number (Tb.N), cortical tissue mineral density (TMD), maximum and minimum moment of inertia (Imax and Imin)

Figure 1.

Representative MicroCT images of femoral trabecular and cortical bone from ALS SOD1G93A and littermate controls. Trabecular bone mass (Tb.BV/TV) and cortical bone thickness (Ct.Th) were lower in ALS SOD1G93A mice than controls. *p<0.05 for Cont vs. ALS. Error bars represent one SEM.

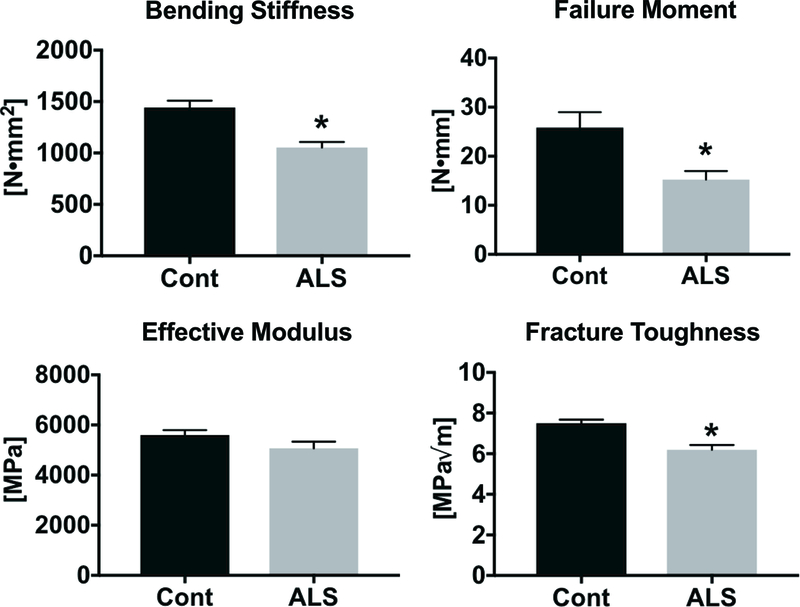

In addition to deficits in bone microstructure, bone functional properties were reduced in ALS SOD1G93A mice. In particular, femoral bending stiffness, maximum moment and failure moment were 27%, 23% and 41% lower, respectively, in ALS SOD1G93A mice (p < 0.005 for all, Table 2, Figure 2). In contrast, the effective modulus, which is derived from the bending stiffness by normalizing to the area moment of inertia, and reflects the intrinsic properties of the bone material, did not differ between groups. Fracture toughness, which assesses the material’s resistance to crack growth, was 18% lower in ALS SOD1G93A mice than controls (p = 0.0006). Similar to the effective modulus, cortical micromechanical properties assessed by cyclic reference point indentation were similar in ALS SOD1G93A mice and their littermate controls.

Table 2:

Femoral and tibial biomechanical properties, assessed by three-point bending and reference point indentation (Mean ± SEM)

| Cont | ALS | % Difference ALS vs. Cont |

p-value ALS vs. Cont |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femur | Bending Stiffness [N•mm2] | 1440 ± 66 | 1050 ± 53 | −27.0 | 0.0002 |

| Effective Modulus [MPa] | 5600 ± 200 | 5070 ± 270 | −9.4 | 0.14 | |

| Failure Moment [N•mm] | 25.9 ± 3.1 | 15.2 ± 1.8 | −41.1 | 0.007 | |

| Maximum Moment [N•mm] | 48.1 ± 2.6 | 37.0 ±1.9 | −23.0 | 0.003 | |

| Tibia | TID [μm] | 36.6±1.4 | 34.3±1.2 | −6.3 | 0.22 |

| IDI [μm] | 5.97±0.4 | 5.42±0.3 | −9.1 | 0.30 | |

| CID [μm] | 1.06±0.1 | 1.01±0.03 | −4.8 | 0.40 | |

Abbreviations: total indentation distance (TID), indentation distance increase (IDI, μm), creep indentation distance (CID).

Figure 2.

Functional assessment of bone in ALS SOD1G93A and littermate controls. Bending stiffness, failure moment, and fracture toughness were lower in ALS SOD1G93A mice than controls. *p<0.05 for Cont vs. ALS. Error bars represent one SEM.

Discussion

While the muscular consequences of ALS have been extensively studied, the effects of ALS on skeleton fragility are less well understood. Our results demonstrate that the whole bone mechanical properties are compromised in ALS SOD1G93A mice. Specifically, the bending stiffness, failure and maximum moments, and fracture toughness were lower in SOD1G93A mice compared to age- and sex-matched littermate controls. In addition, we found that femoral trabecular and cortical bone mass and microstructure are compromised in ALS SOD1G93A mice, consistent with a prior report (5).

It is likely that the lower femoral bending properties in ALS SOD1G93A mice are due primarily to a secondary effect of impaired muscle function and reduced physical activity in these mice, rather than a direct effect of the SOD1G93A mutation on bone. In our study, ALS mice showed a very low compound motor action potential amplitude (15.4 ± 2.8 mV) and markedly reduced motor unit number estimate (38.8 ± 6.5 Motor Units) compared to values observed in healthy animals (6, 12–14). In addition, clinical and preclinical studies have demonstrated that ALS leads to decreased muscle mass, cross-sectional area, and strength (13, 15, 16). Decreased muscle cross-sectional area has been correlated with decreased bone area (17), which can lead to increased fracture risk (18). Also, bed rest studies demonstrate that calf muscle cross sectional area decreases more rapidly compared to bone mineral content in the tibial epiphysis (19). This rapid decline in muscle function leads to reduced mechanical loading environment on bone, which subsequently leads to reduced bone mass and area as the bone adapts to the reduced mechanical loads (20). Stimulating muscle contractions in hindlimb suspended rats prevents bone loss associated with unloading, providing evidence of the key connection between of muscular contraction and bone metabolism (21). Altogether, these studies suggest that functional impairment of bone in ALS SOD1G93A mice is secondary to declines in neuromuscular function.

While reduced bone strength is likely largely secondary to impairments in skeletal muscle function in ALS SOD1G93A mice, clinical studies suggest that the skeletal deficits may occur independent of skeletal muscle deficits, as the increased incidence of bone fractures precedes the ALS diagnosis by as much as 10 years (1, 22). In ALS SOD1G93A mice, mitochondrial dysfunction was observed in cortical bone osteocytes due to accumulation of mutant SOD1G93A protein (23). To determine if mitochondrial dysfunction continues despite absence of skeletal muscle atrophy, mutant SOD1G93A protein was overexpressed in the osteocytic cell line MLO-Y4 cells. In addition to increased mitochondrial dysfunction, MLO-Y4 cells overexpressing SOD1G93A protein showed increased apoptosis. Osteocyte apoptosis is associated with increased RANKL, which promotes osteoclastic bone resorption and subsequent bone loss and microarchitectural deterioration (24). These studies suggest that in addition to reduced mechanical loading on bone due to skeletal muscle atrophy, altered bone cell homeostasis mutation may contribute to skeletal fragility and increased skeletal fracture risk in ALS patients.

Limitations of current studies include a lack of functional assessment of bone in male ALS mice. Fracture risk may differ in male versus female ALS patients, as studies in similarly-aged healthy cohorts show that women have up to a 4-fold higher fracture incidence than men (25). Also, to determine the underlying cause of increased fracture incidence prior to ALS diagnosis, future studies should examine bone functional assessments at earlier time points in the ALS SOD1G93A mice. Finally, since SOD1G93A mutation is only presented in a small fraction of ALS patients, other mouse models with different genetic mutations (C9orf72, TDP-43, FUS, VCP) that also lead to ALS should be examined to determine if bone functional properties are also similarly altered in these models (26).

In conclusion, our study is the first to demonstrate that in addition to impairment of skeletal muscle function, ALS SOD1G93A mice exhibit skeletal fragility, as indicated by reduced femoral bending properties and fracture toughness compared to control mice. These results have important implications. As new treatments are introduced that extend the survival of ALS patients, targeted therapies to prevent skeletal fractures should also be considered, including drugs that inhibit bone resorption, such as bisphosphonates or denosumab, and drugs that promote bone formation, such as teriparatide or abaloparatide. Ultimately, fracture prevention may be proven to be an important aspect of sustaining quality of life among longer-surviving ALS patients.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dimitrios Psaltos for assistance during microCT scanning and analysis.

Funding: This work was supported by NASA NNX16AL36G and NIH R01-NS055099

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Peters TL, Weibull CE, Fang F, Sandler DP, Lambert PC, Ye W, et al. Association of fractures with the incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2017;18(5–6):419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown RH, Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017;377(2):162–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato Y, Honda Y, Asoh T, Kikuyama M, Oizumi K. Hypovitaminosis D and decreased bone mineral density in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur Neurol 1997;37(4):225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanis JA. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporos Int 1994;4(6):368–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu K, Yi J, Xiao Y, Lai Y, Song P, Zheng W, et al. Impaired bone homeostasis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice with muscle atrophy. J Biol Chem 2015;290(13):8081–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Sung M, Rutkove SB. Electrophysiologic biomarkers for assessing disease progression and the effect of riluzole in SOD1 G93A ALS mice. PLoS One 2013;8(6):e65976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jepsen KJ, Silva MJ, Vashishth D, Guo XE, van der Meulen MC. Establishing biomechanical mechanisms in mouse models: practical guidelines for systematically evaluating phenotypic changes in the diaphyses of long bones. J Bone Miner Res 2015;30(6):951–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritchie RO, Koester KJ, Ionova S, Yao W, Lane NE, Ager JW, 3rd. Measurement of the toughness of bone: a tutorial with special reference to small animal studies. Bone 2008;43(5):798–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devlin MJ, Van Vliet M, Motyl K, Karim L, Brooks DJ, Louis L, et al. Early-onset type 2 diabetes impairs skeletal acquisition in the male TALLYHO/JngJ mouse. Endocrinology 2014;155(10):3806–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen MR, McNerny EM, Organ JM, Wallace JM. True Gold or Pyrite: A Review of Reference Point Indentation for Assessing Bone Mechanical Properties In Vivo. J Bone Miner Res 2015;30(9):1539–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Muller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25(7):1468–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancuso R, Santos-Nogueira E, Osta R, Navarro X. Electrophysiological analysis of a murine model of motoneuron disease. Clin Neurophysiol 2011;122(8):1660–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Pacheck A, Sanchez B, Rutkove SB. Single and modeled multifrequency electrical impedance myography parameters and their relationship to force production in the ALS SOD1G93A mouse. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2016;17(5–6):397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Geisbush TR, Arnold WD, Rosen GD, Zaworski PG, Rutkove SB. A comparison of three electrophysiological methods for the assessment of disease status in a mild spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. PLoS One 2014;9(10):e111428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobrowolny G, Aucello M, Rizzuto E, Beccafico S, Mammucari C, Boncompagni S, et al. Skeletal muscle is a primary target of SOD1G93A-mediated toxicity. Cell Metab 2008;8(5):425–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutkove SB, Caress JB, Cartwright MS, Burns TM, Warder J, David WS, et al. Electrical impedance myography correlates with standard measures of ALS severity. Muscle Nerve 2014;49(3):441–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rittweger J, Beller G, Ehrig J, Jung C, Koch U, Ramolla J, et al. Bone-muscle strength indices for the human lower leg. Bone 2000;27(2):319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riggs BL, Melton Iii LJ, 3rd, Robb RA, Camp JJ, Atkinson EJ, Peterson JM, et al. Population-based study of age and sex differences in bone volumetric density, size, geometry, and structure at different skeletal sites. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19(12):1945–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rittweger J, Frost HM, Schiessl H, Ohshima H, Alkner B, Tesch P, et al. Muscle atrophy and bone loss after 90 days’ bed rest and the effects of flywheel resistive exercise and pamidronate: results from the LTBR study. Bone 2005;36(6):1019–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burr DB. Muscle strength, bone mass, and age-related bone loss. J Bone Miner Res 1997;12(10):1547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swift JM, Nilsson MI, Hogan HA, Sumner LR, Bloomfield SA. Simulated resistance training during hindlimb unloading abolishes disuse bone loss and maintains muscle strength. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25(3):564–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gresham LS, Molgaard CA, Golbeck AL, Smith R. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and history of skeletal fracture: a case-control study. Neurology 1987;37(4):717–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, Yi J, Li X, Xiao Y, Dhakal K, Zhou J. ALS-associated mutation SOD1(G93A) leads to abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in osteocytes. Bone 2018;106:126–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cabahug-Zuckerman P, Frikha-Benayed D, Majeska RJ, Tuthill A, Yakar S, Judex S, et al. Osteocyte Apoptosis Caused by Hindlimb Unloading is Required to Trigger Osteocyte RANKL Production and Subsequent Resorption of Cortical and Trabecular Bone in Mice Femurs. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31(7):1356–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, de Laet CE, Burger H, Seeman E, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone 2004;34(1):195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGoldrick P, Joyce PI, Fisher EM, Greensmith L. Rodent models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1832(9):1421–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]