Abstract

Although parenting is one of the most commonly studied predictors of child problem behavior, few studies have examined parenting as a multidimensional and dynamic construct. This study investigated different patterns of developmental trajectories of two parenting dimensions (harsh discipline [HD] and parental warmth [PW]) with a person-oriented approach, and examined the associations between different parenting patterns and child externalizing problems and callous-unemotional traits. Data were drawn from the combined high-risk control and normative sample (n = 753) of the Fast Track Project. Parent-reported HD and observer-reported PW from kindergarten to Grade 2 were fit to growth mixture models. Two subgroups were identified for HD (low decreasing, 83.0%; high stable, 17.0%) and PW (high increasing, 78.7%; low increasing, 21.3%). The majority of parents (67.0%) demonstrated the low decreasing HD and high increasing PW pattern, while the prevalence of the high stable HD and low increasing PW pattern was the lowest (6.8%). Parenting satisfaction, parental depression, family socioeconomic status, and neighborhood safety predicted group memberships jointly defined by the two dimensions. Children from the high stable HD and low increasing PW pattern showed the highest levels of externalizing problems in Grades 4 and 5. Children from the low decreasing HD and low increasing PW pattern showed the highest levels of callous-unemotional traits in Grade 7. These findings demonstrate the utility and significance of a person-oriented approach to measuring parenting as a multidimensional and dynamic construct, and reveal the interplay between HD and PW in terms of their influences on child developmental outcomes.

Keywords: parental warmth, harsh discipline, externalizing problems, developmental trajectory, person-oriented approach

Parenting has a potent impact on the socialization of children, and different dimensions of parenting are associated with various child and adolescent outcomes. For instance, harsh discipline (HD) and low levels of parental warmth (PW) are implicated in the emergence of antisocial outcomes in childhood, including externalizing problems (Deater-Deckard et al. 1996; Rothbaum and Weisz 1994) and callous-unemotional (CU) traits (e.g., lack of guilt and empathy) (Waller et al. 2013). As such, evidence-based preventive interventions focus on improving parenting practices to prevent child and adolescent problem behaviors (Sandler et al. 2011).

Parenting is a dynamic construct that changes over time, dependent on the reciprocal relationship with child outcomes and specific developmental periods (Pardini 2008; Pettit and Arsiwalla 2008). However, prior studies typically include parenting assessed at a single time point as a predictor of child outcomes. For instance, Prinzie et al. (2005) reported that higher HD was associated with slower decrease of aggressive behaviors over 3 years in children aged 4–7 years. Barnes et al. (2000) found that higher parental monitoring predicted slower increase of adolescent alcohol misuse over 6 years. Relatively few longitudinal studies have examined developmental trajectories of parenting, notably during early and middle childhood. Prior studies have shown that parent-child warmth did not change or increase in middle childhood but decreased from early to mid-adolescence (Shanahan et al. 2007a) and that parent-child conflict generally decreased throughout adolescence, but its peak was timed with the firstborns’ transition into adolescence (Shanahan et al. 2007b). Parental monitoring generally decreases from childhood through adolescence (e.g., Pettit et al. 2007). Notably in one study, Simon et al. (2001) assessed inept parenting (a composite measure of parental monitoring, HD, consistent discipline, and inductive reasoning) and deviant peer affiliation over 4 years in adolescents aged 12–13 years, and found that higher increase of inept parenting predicted higher increase of deviant peer affiliation. Therefore, examining the developmental trajectory of parenting could shed light on associations between its change and the change of child outcomes to elucidate developmental processes (Pardini 2008;Pettit and Arsiwalla 2008).

In addition to being dynamic, parenting is multifaceted and includes both positive and negative dimensions (Power 2013). PW is a relationship-based aspect of parenting and involves positive affect (MacDonald 1992), whereas HD is a goal-directed parenting practice and involves negative affect (Patterson et al. 1992). In families of early school-aged children, parents frequently use discipline and/or warmth to gain child compliance; the former strategy can rapidly escalate to HD in the context of coercive parent-child interactions (Patterson et al., 1992). Thus, both HD and PW are particularly salient during the early school-age period and are robust predictors of later externalizing outcomes (Deater-Deckard and Dodge 1997; Deater-Deckard et al. 1996; Rothbaum and Weisz 1994). Although these parenting dimensions are theoretically distinct, they are negatively correlated (Pardini et al. 2007; Waller et al. 2015). Moreover, one dimension of parenting may augment the effects of another. That is, parenting dimensions can interact throughout development (Darling and Steinberg 1993; Power 2013). For instance, high levels of PW have been shown to reduce the negative effects of HD on child externalizing problems (Deater-Deckard and Dodge 1997; McKee et al. 2007). In this light, it is surprising that few studies have examined parenting as a multidimensional and dynamic construct. One study assessed PW and harsh punishment annually over 6 years in a large group of 7–12 years old girls, and found that both dimensions uniquely predicted girls’ conduct problems (Hipwell et al. 2008). However, the developmental trajectories of PW and punishment were not examined.

Most previous research has assessed parenting with a variable-oriented approach, which assumes that the associations among parenting variables themselves and with child outcomes are the same across all individuals. However, parenting dimensions are not expressed alone but interact with other dimensions in a complex and transactional system; different parents demonstrate different parenting patterns or styles (Baumrind 1991; Darling and Steinberg 1993; Power 2013). For example, some parents may demonstrate high levels of both PW and HD, whereas other parents may exhibit low levels of PW and high levels of HD. To capture homogenous subgroups of parents who demonstrate similar parenting patterns, and to examine the associations of different parenting patterns with child outcomes, it is necessary to adopt a person-oriented approach to the measuring of parenting. A person-oriented approach takes a holistic view toward multiple dimensions of parenting, and can be particularly helpful in identifying unique combinations of parenting dimensions that interactively and synergistically predict child outcomes, which would otherwise be statistically difficult to detect with a variable-oriented approach such as multiple regression (e.g., 3- or 4-way interaction). Particularly, as opposed to examining the association between parenting measured at a single time point and child outcomes, using the person-oriented approach to investigate different developmental trajectories of parenting measured at multiple time points can elucidate the relationships between different patterns of change of parenting and child outcomes. This could inform future intervention research and design because family-focused interventions essentially aim to improve child outcomes by influencing (i.e., change) parenting practices (Sandler et al. 2011).

The utility and validity of a person-oriented approach has been demonstrated in studies examining various developmental risks and child outcomes (e.g., Lanza and Rhoades 2013; Lanza et al. 2010). Only a few studies, however, have adopted a person-oriented approach to examine developmental trajectories of parenting and/or their associations with child and adolescent outcomes. Laird et al. (2009) identified three developmental trajectories of parental supervision in a group of 12–16 year-old adolescents: low decreasing, moderate stable, and high stable. Tobler and Komro (2010) examined developmental trajectories of parental monitoring and communication from grades 6 to 8 and identified four trajectories: high, medium, decreasing, and inconsistent. Adolescents in the decreasing and inconsistent group were at greater risk for drug use at grade 8 relative to those in the high group. Van Ryzin and Dishion (2012) identified five trajectories of parental monitoring from age 12 to 17: high, moderate, rising, declining, and low. Adolescents in the high parental monitoring group had the lowest level of externalizing problems at age 19. While these three studies only examined single dimensions of parenting, Luyckx et al. (2011) examined dynamic parenting patterns defined by developmental trajectories of three dimensions (monitoring, positive parenting, and inconsistent discipline) from grades 1 to 12. Children from the group with high and increasing (as opposed to stable) levels of monitoring, high and stable (as opposed to decreasing) levels of positive parenting, as well as low levels of inconsistent discipline, showed the lowest levels of externalizing problems and substance use. Using a small sample followed from age 5 to 15, Trentacosta et al. (2011) identified three developmental trajectories of mother-son warmth: high quadratic, moderate decreasing, and low decreasing, and four trajectories for mother-son conflict: high stable, high decreasing, moderate quadratic, and low quadratic. Notably, the two high conflict groups (but not warmth group memberships) had higher levels of adolescent antisocial behavior than the low conflict group.

The Current Study

These findings demonstrate the utility of a person-oriented approach to capture parenting as a multidimensional and dynamic construct. However, to address significant limitations in prior studies, further research is needed that includes PW and HD and examines developmental patterns of key parenting dimensions across the critical first few years of school when problem behavior first emerges for many children (Deater-Deckard and Dodge 1997; Deater-Deckard et al. 1996; Rothbaum and Weisz 1994). In light of the multifaceted nature of child antisocial outcomes, there is also a priority for research that focuses on relations between parenting and both externalizing problems and CU traits. CU traits mark a particularly severe trajectory of externalizing problems; however, these traits can also be elevated in the absence of high levels of externalizing problems (Viding and McCrory 2012) and are studied as a subset of antisocial behavior. For instance, prior results from a study that included a subset (54%) of the current sample showed that HD and PW were differentially linked to externalizing problems and CU traits, respectively (e.g., Pasalich et al. 2016). Moreover, CU traits predict long-term antisocial outcomes over and above baseline levels of externalizing problems (e.g., McMahon et al. 2010). Thus, we examined externalizing problems in grades 4 and 5 as well as the most proximal assessment of CU traits, which occurred in grade 7.

There were three goals in the current study: 1) identify the developmental patterns of PW and HD from kindergarten to grade 2 separately and jointly; 2) examine the prediction of different developmental patterns of parenting by parent (parenting efficacy and satisfaction, parental depression), family (socioeconomic status [SES]), and neighborhood (neighborhood safety) variables that have demonstrated associations with parenting, parent-child relationships, and child outcomes (e.g., Belsky 1984; Dodge et al. 1994; Downey and Coyne 1990; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000); and 3) examine associations of different developmental patterns of parenting with externalizing problems and CU traits in late childhood. Based on prior work (e.g., Trentacosta et al. 2011), we expected that there would be: a) subgroups of parents that demonstrate different developmental patterns for HD (e.g., high stable, decreasing) and for PW (e.g., decreasing, increasing); b) different developmental patterns of HD and PW would be predicted by parent, family, and neighborhood variables; and that c) relatively problematic parenting patterns (i.e., involving higher levels of HD and/or lower levels of PW) would be associated with elevated levels of externalizing problems and CU traits.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were drawn from a community-based sample of children from the Fast Track project, a longitudinal multisite investigation of the development and prevention of childhood conduct problems (CPPRG 1992, 2000). Participants were recruited from four distinct school sites: Durham, NC; Nashville, TN; Seattle, WA; and rural Pennsylvania. In 1991–1993, 9,594 kindergarteners across three cohorts were screened by teachers for classroom conduct problems, and a subset of these participants were then screened for home behavior problems using a parent- report measure. After the multiple-gating screening procedure, children were selected for the high-risk sample (control = 446, intervention = 445) and the normative sample (n = 387). The current study combined data from the high-risk control group (65% male; 49% African American, 48% European American, 3% other race) and normative (51% male; 43% African American, 52% European American, 5% other race) sample. With 79 of those recruited for the high-risk control group included as part of the normative sample, the sample includes 753 participants (1 participant was excluded from analyses because of a missing weighting value). Informed written consent from parents and oral assent from children were obtained. Parent(s) were compensated with $75 for completing each of the summer interviews while teachers were paid $10/child each year for completing all classroom measures.

Measures

Covariates.

The covariates included sex (male = 58%), race/urban status (urban Black = 46.0%, urban White = 24.2%, rural White = 25.7%), total severity-of-risk screen score summed from standardized teacher and parent screening scores (M = 1.01, SD = 1.64, ranging from −3 to 5), age at the start of the project (M = 6.54 years, SD = .58), and cohort (cohort 1 = 61.4%, cohort 2 = 21.4%, cohort 3 = 17.2%).

Parental warmth.

In the summers following kindergarten (6–7 years old), grade 1 (7–8 years old), and grade 2 (8–9 year old), participants and their mothers completed the Parent-Child Interaction Task (PCIT) at home. The PCIT included four tasks: Child’s Game (5 minutes), Parent’s Game (5 minutes), Lego Task (5 minutes), and Clean-Up (3 minutes). After each task, an observer completed the Interaction Rating Scale (IRS; Crnic and Greenberg 1990). The IRS includes a 5-point rating system (1 = low or negative value; 5 = high or positive value) of 16 global items of parent-child interaction based on gratification, sensitivity, and involvement. PW was calculated by using the mean of six items that were coded across the four different tasks (interrater intraclass correlation coefficient = .73). The items were related to maternal gratification (e.g., enjoyment in the interaction with the child), sensitivity (e.g., sensitive responding to the child’s cues), and involvement (e.g., time spent interacting with the child). The αs ranged from .87 to .92 across three time points.

Harsh discipline.

As part of the summer interview after kindergarten, grade 1, and grade 2, parents answered the Life Changes Interview (Dodge et al. 1990), which assessed constructs related to the parent-child relationship, developmental history, child-care, and discipline strategies. Parents were asked how they would handle six different situations of child misbehavior – delivered in the form of short written vignettes (e.g., hitting another child, noncompliance). Their responses were coded into one of several mutually exclusively categories (e.g., inductive reasoning, withdrawal of privileges, proactive guidance, physical punishment). Responses were coded as 0 (not mentioned), 1 (mentioned), or 2 (typical). The physical punishment subscale was used, with the overall score computed by averaging parents’ responses across the six vignettes; αs ranged from .41 to .57 across three time points. Despite a relatively low α which was possibly due to its smaller potential range (0–2) and generally low levels in the sample (means between .21–.12 across waves), the high inter-rater correlation coefficient for HD (.93) available for a subset of the combined Fast Track high-risk intervention and control sample partly supports the reliability of this measure (CPPRG 1992).

Parenting efficacy and satisfaction.

In the summer following kindergarten, parents completed a 12-item questionnaire, Being A Parent, adapted from the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (Johnston and Mash 1989) to assess competency, problem-solving ability, and capability in the parenting role (efficacy; 6 items, α = .76), and parenting frustration, anxiety, and motivation (satisfaction; 6 items, α = .74). Parents read a series of statements about parenting and responded on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree).

Parental depression.

In the summer following kindergarten, parents completed the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (Radloff 1977), assessing current levels of depressive symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale based on how frequently the experience occurred during the previous week (1 = “less than 1 day,” 2 = “1–2 days,” 3= “3–4 days,” and 4 = “5–7 days”) (α =.88).

Neighborhood safety.

In the summer following kindergarten, parents completed the 16-item Neighborhood Questionnaire (CPPRG 1991), assessing satisfaction with the families’ neighborhood. The Neighborhood Safety Subscale was used, composed of five items assessing the incidence of violent crime, neighborhood drug traffic, and local police protection (α = .81).

SES.

Parents completed the Family Information Form (FIF; CPPRG 1990) in the summer following kindergarten, which assessed demographic information as well as SES, and family structure and composition information. Using a formula derived by Hollingshead (1975), the SES Continuous Code was created. The score was “calculated by multiplying the scale value for an occupation by a weight of five and the scale value for education by a weight of three” (Hollingshead 1975). Higher scores indicated higher SES.

Externalizing symptoms.

Externalizing symptoms were measured using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991a). Parents answered questions about their child’s behavior problems and competencies using a 3-point Likert scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true). Nationally normed t scores from the Externalizing broad-band scale (33 items) obtained in grades 4 and 5 (αs = .90 and .91) were used, the two time points with available externalizing measures immediately after the final assessment of parenting in grade 2. A similar measure, the Teacher’s Report Form (TRF; Achenbach 1991b) was given to teachers to rate their students on the same 3-point Likert scale. T scores from the Externalizing scale (34 items) obtained in grades 4 and 5 (αs = .97 and .96) were used.

CU traits.

The Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD; Frick and Hare 2001) was used to assess youth CU traits. The parent-report was administered during the summer after the participants completed grade 7. The APSD is a 20-item scale that assesses CU traits, narcissism, and impulse control/conduct problems in youth on a 3-point scale (0 = not at all true, 1 = sometimes true, 2 = definitely true). The 6-item CU traits subscale has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity in prior research (e.g., McMahon et al. 2010) and in this study, α = .65. Example items (reverse-scored) include: “Is concerned about the feelings of others” and “Feels bad or guilty when he/she does something wrong.”

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS 19.0 and growth mixture modeling was done in Mplus 7.2 (Muthen and Muthen 1998–2012). All variables including covariates, predictors, and outcomes were generally normally distributed (skewness between −0.81 and 1.42, kurtosis between −0.64 and 3.29); therefore, raw scores were used in analyses without transformation. The retention rates were high (>91%, 86%, and 82% in grade 2, 5, and 7, respectively) with low missing data. Full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to handle missing data, so participants with at least one available outcome measure were all included in analyses (Rubin and Little 2002). A probability weight was used in all analyses to account for the oversampling of high-risk children (Jones et al. 2002). A maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR) that are robust to non-normality of the data was used in all analyses. Starting from 1-class up to a 4-class solution, multiple models (500) with randomly generated starting values were run for each solution to avoid local optima. The Lo- Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT; Lo et al. 2001) was used to choose the best model. A significant LMR-LRT p value indicates that a model with k classes fits better than the model with k-l classes. In addition, a number of fit indices based on information criteria were also employed to help choose the best model (the smaller the better): Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the sample size-adjusted BIC (aBIC) (Nylund et al. 2007). After the best class solution was chosen, predictors and covariates were included simultaneously in multinomial logistic regressions to predict group membership in Mplus 7.2. Finally, child externalizing problems and CU traits were included as distal outcomes for their pairwise mean difference comparisons between latent groups using the Waldχ2 test.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

As shown in Table 1, PW and HD demonstrated modest and significant negative correlations (rs between −.12 and −.21) across all three time points. Generally, the mean levels of PW increased, while HD decreased, from kindergarten to grade 2. Notably, the low levels of HD suggested that most parents in the sample rarely endorsed any HD. Parenting satisfaction, neighborhood safety, and SES positively correlated with PW and negatively with HD, while parental depression showed the opposite pattern. PW correlated negatively, and positively for HD, with child externalizing problems and CU traits.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Parenting Variables, Predictors, and Child Outcomes

| PWK | PW1 | PW2 | HDK | HDK | HDK | PEK | PSK | PDK | NSK | SESK | CBC4 | CBC5 | TRF4 | TRF5 | CU7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PW1 | .42** | |||||||||||||||

| PW2 | .35** | .49** | ||||||||||||||

| HDK | −.15** | −.21** | −.18** | |||||||||||||

| HD1 | −.21** | −.14** | −.12** | .41** | ||||||||||||

| HD2 | −.16* | −.15** | −.13** | .30** | .35** | |||||||||||

| PEK | .01 | −.05 | .02 | −.11** | −.04 | −.01 | ||||||||||

| PSK | .18** | .19** | .20** | −.18** | −.17** | −.14** | .22** | |||||||||

| PDK | −.16** | −.22** | −.26** | .22** | .18** | .09* | −.17** | −.40** | ||||||||

| NSK | .22** | .18** | .20** | −.12** | −.07 | −.10** | .00 | .18** | −.23** | |||||||

| SESK | .28** | .35** | .28** | −.16** | −.15** | −.08* | −.02 | .25** | −.30** | .31** | ||||||

| CBC4 | −.04 | −0.80* | −.16** | .18** | .11** | .07 | −.25** | −.30** | .27** | −.08 | −.13** | |||||

| CBC5 | −.05 | −2.12** | −.19** | .19** | .15** | .13** | −.21** | −.26** | .22** | −.09* | −.15** | .78** | ||||

| TRF4 | −.15** | −.17** | −.15** | .18** | .12** | .13** | −.06 | −.18** | .24** | −.22** | −.24** | .38** | .36** | |||

| TRF5 | −.16** | −.15** | −.19** | .10* | .10* | .07 | −.02 | −.13** | .17** | −.18** | −.18** | .34** | .31** | .64** | ||

| CU7 | −.16** | −.25** | −.21** | .09* | .10* | .07 | −.11** | −.16** | .21** | −.16** | −.29** | .31** | .32** | .30** | .26** | - |

| M | 3.52 | 3.67 | 3.65 | .21 | .19 | .12 | 5.58 | 4.06 | 14.92 | 32.86 | 25.66 | 54.12 | 53.08 | 58.73 | 57.42 | .63 |

| (SD) | (.79) | (.82) | (.84) | (.23) | (.22) | (.16) | (0.79) | (1.19) | (10.06) | (11.74) | (12.90) | (11.62) | (11.84) | (11.87) | (11.32) | (.37) |

p < .01.

p < .05.

Note. PW = parental warmth. HD = harsh discipline. PE = parenting efficacy. PS = parenting satisfaction. PD = parental depression. NS = neighborhood safety. SES = socioeconomic status. CBC = parent-reported CBCL externalizing problems t scores. TRF = teacher’s report form of CBCL externalizing problems t scores. CU = callous-unemotional traits. K = kindergarten. Numbers (1–2, 4–5, 7) represents grades.

Developmental Patterns of Harsh Discipline and Parental Warmth

Supplemental Table 1 provides fit indices of 1-through 4-class models for HD and PW, respectively. For HD, the significant LMR-LRT (p = .043) for the 2-class solution suggested a better fit of the 2-class model over 1-class model. The information criteria of the 2-class solution (AIC = −1508.49, BIC = −1462.25, aBIC = −1494.01) were lower than that of the 1-class solution (AIC = −1344.34, BIC = −1311.97, aBIC = −1334.20). Despite lower information criteria than the 2-class solution (AIC = −1630.64, BIC = −1570.52, aBIC = −1611.80), the non-significant LMR-LRT (p = .742) for the 3-class solution suggested that including the third class (which had an estimated prevalence of 3.5%) did not significantly improve the model fit. Therefore, based on parsimony and interpretation, the 2-class model was selected for HD (entropy = .87). Similarly for PW, compared to the 1-class solution (AIC = 4792.06, BIC = 4815.18, aBIC = 4799.30), the 2-class solution had lower information criteria (AIC = 4591.62, BIC = 4633.22, aBIC = 4604.64), and significant LMR-LRT (p = .005). The 3-class solution had lower information criteria (AIC = 4564.63, BIC = 4615.48, aBIC = 4580.55) but non-significant LMR-LRT (p = .056). Therefore, the 2-class model was selected (entropy = .74).

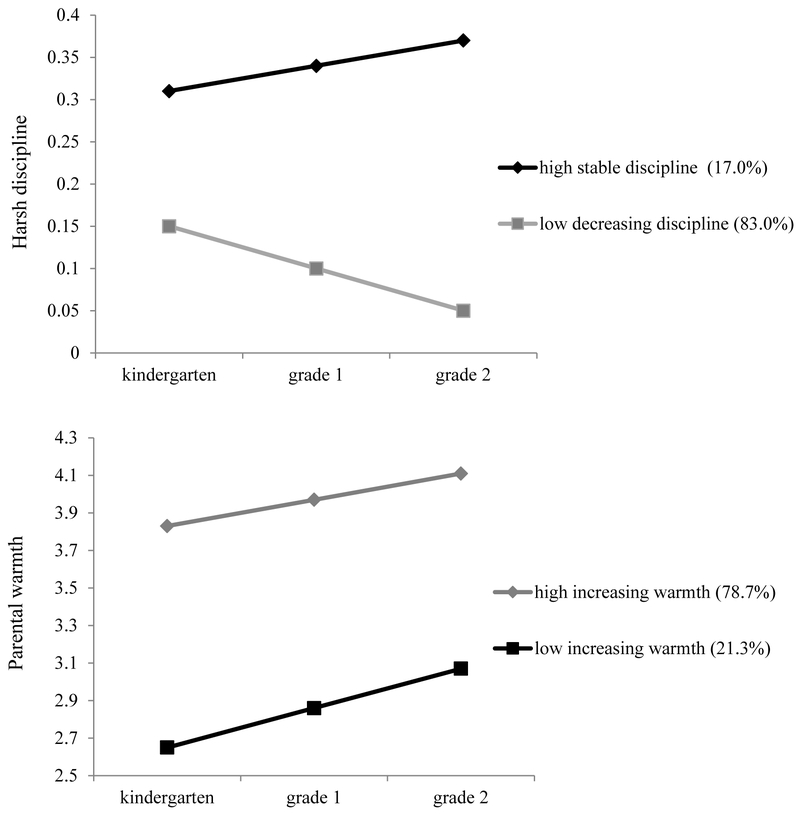

Figure 1 shows the estimated developmental trajectories in the 2-class model for HD and PW. For HD, the majority of parents belonged to a normative group (83.0%) with lower levels of HD at kindergarten (0.15, SE = 0.01, p < .001) that decreased (−0.05, SE = 0.01, p < .001) through grades 1 and 2, labeled as low decreasing discipline (LDD). The other group had a smaller prevalence (17.0%) with higher levels of HD at kindergarten (0.31, SE = 0.03, p < .001) that remained generally stable (0.03, SE = 0.02, ns) through grade 1 and 2, labeled as high stable discipline (HSD). For PW, the majority of parents belonged to a normative group (78.7%) with higher levels of PW at kindergarten (3.83, SE = 0.05, p < .001) that increased (0.14, SE = 0.04, p < .001) through grades 1 and 2, labeled as high increasing warmth (HIW). The other group had a smaller prevalence (21.3%) with lower levels of PW at kindergarten (2.65, SE = 0.17, p < .001) that increased (0.21, SE = 0.10, p < .05) through grades 1 and 2, labeled as low increasing warmth (LIW). The majority of parents (67.0%, n = 522) demonstrated the relatively normative pattern of LDD-HIW, whereas the prevalence of parents showing the relatively problematic patterns of HSD-LIW was the smallest (6.8%, n = 46). About 15.8% (n = 113) parents showed the LDD-LIW pattern, whereas 10.4% (n = 71) parents showed the HSD-HIW pattern.

Figure 1.

Developmental trajectories of harsh discipline (top) and parental warmth (bottom).

Predictions of Developmental Patterns of Parenting

We first examined the prediction of group membership for each parenting dimension alone. Neither the parenting variables nor parental depression predicted group membership for either HD or PW (see Supplemental Table 2). Family SES predicted group membership for PW; neighborhood safety did so marginally. Specifically, parents from families with higher SES (B = −.07, OR = 0.94, p < .01) or who lived in safer neighborhoods (B = −0.05, OR = 0.95, p = .052) were less likely to be in the LIW group than in the HIW group. Neither family SES nor neighborhood safety predicted group membership for HD.

The prediction revealed more nuanced results when predicting the joint developmental patterns of HD and PW (Table 2). Specifically, parents with higher depressive symptoms (B = 0.08, OR = 1.08, p < .05) or from families with lower SES (B = −0.13, OR = 0.88, p < .01) were more likely to be in the HSD-LIW group than to be in the LDD-HIW group. Parental depression also put parents at higher risk of being in the HSD-LIW group than in either the LDD-LIW group (B = 0.10, OR = 1.10, p < .05) or in the HSD-HIW group (B = 0.12, OR = 1.13, p < .05). Parents with lower parenting satisfaction (B = −0.61, OR = 0.54, p < .05), from families with lower SES (B = −0.06, OR = 0.94, p < .01), and/or from less safe neighborhoods (B = −0.10, OR = 0.91, p < .01) were more likely to be in the LDD-LIW group than in the LDD-HIW group. Finally, parents from less safe neighborhoods (B = −0.13, OR = 0.88, p < .01) were more likely to be in the HSD-HIW group than in the LDD-HIW group.

Table 2.

Joint Group Membership Prediction with Multinomial Logistic Regression

| HSD-LIWa | LDD-LIWa | HSD-HIWa | HSD-LIWb | HSD-HIWb | HSD-LIWc | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | OR | B (SE) | OR | B (SE) | OR | B (SE) | OR | B (SE) | OR | B (SE) | OR | ||

| Parenting efficacy | 0.49 (0.40) | 1.63 | 0.43 (0.31) | 1.53 | 0.76 (0.68) | 2.14 | 0.06 (0.43) | 1.06 | 0.34 (0.65) | 1.40 | −0.27 (0.90) | 0.76 | |

| Parenting satisfaction | 0.05 (0.39) | 1.05 | −0.61 (0.28)* | 0.54 | −0.56 (0.32) | 0.57 | 0.66 (0.47) | 1.93 | 0.05 (0.27) | 1.05 | 0.61 (0.52) | 1.84 | |

| Parental depression | 0.08 (0.03)* | 1.08 | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.98 | −0.05 (0.04) | 0.96 | 0.10 (0.04)* | 1.10 | −0.02 (0.04) | 0.98 | 0.12 (0.05)* | 1.13 | |

| SES | −0.13 (0.05)** | 0.88 | −0.06 (0.02)** | 0.94 | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.98 | −0.07 (0.05) | 0.93 | 0.04 (0.02) | 1.04 | −0.11 (0.06) | 0.90 | |

| Neighborhood safety | 0.00 (0.07) | 1.00 | −0.10 (0.04)** | 0.91 | −0.13 (0.04)** | 0.88 | 0.10 (0.09) | 1.10 | −0.03 (0.03) | 0.97 | 0.13 (0.09) | 1.14 | |

p < .01.

p < .05.

LDD-HIW group as the reference group.

LDD-LIW group as the reference group.

HSD-HIW group as the reference group. Note. OR = odds ratio. HSD = high stable discipline. LIW = low increasing warmth. LDD = low decreasing discipline. HIW = high increasing warmth.

As for covariates, children with higher total severity-of-risk score were more likely to be in the LDD-LIW (B = 0.60, OR = 1.82, p < .01) or the HSD-HIW group (B = 0.74, OR = 2.10, p < .01) than in the LDD-HIW group. Older children were more likely to be in the LDD-LIW (B = 0.98, OR = 2.67, p < .05) than in the LDD-HIW group; and less likely to be in the HSD-HIW (B = −1.05, OR = 0.35, p < .05) than in the LDD-LIW group.

Developmental Patterns of Parenting with Child Externalizing Problems and CU Traits

The associations between different parenting patterns and child outcomes were also examined first for each parenting dimension alone (see Supplemental Table 3). Children in the HIW group consistently showed significantly lower levels of parent- and teacher-reported externalizing problems and CU traits, except for parent-reported grade 4 externalizing problems, than the LIW group. For HD, however, children in the LDD group showed lower levels of externalizing problems than children in the HSD group, but only reached significance for parent-reported externalizing problems at grade 5. Notably, the levels of CU traits were not significantly different between the two groups.

For parent-reported child externalizing problems, children of parents in the HSD-LIW group demonstrated significantly higher levels of externalizing problems (M = 55.69, SE = 3.07) than children of parents in the LDD-HIW group (M = 48.95, SE = 0.86) in grades 4 and 5 (M = 54.11, SE = 3.34 vs. M = 47.22, SE = 0.88) (see Table 3). For teacher-reported child externalizing problems, children of parents in both the HSD-LIW and the LDD-LIW groups engaged in significantly higher levels of externalizing problems (M = 63.96, SE = 2.84 and M = 57.05, SE = 1.88, respectively) than children of parents in the HSD-HIW group (M = 49.97, SE = 1.58), or children of parents in the LDD-HIW group (M = 51.31, SE = 0.84) in grade 4. The same pattern was observed in grade 5: children in the HSD-LIW group (M = 60.03, SE = 2.55) and LDD-LIW group (M = 59.48, SE = 2.48) both showed significantly higher levels of externalizing problems than children in the HSD-HIW group (M = 53.25, SE = 1.83) and LDD-HIW group (M = 51.85, SE = 0.98). In grade 7, children of parents in the LDD-LIW group showed significantly higher levels of parent-reported CU traits (M = 0.75, SE = 0.06) than children of parents in the LDD-HIW group (M = 0.44, SE = 0.04) or in the HSD-HIW group (M = 0.47, SE = 0.06).

Table 3.

Child Externalizing Problems between Groups

| HSD-LIW (n = 46) |

LDD-LIW (n= 113) |

HSD-HIW (n = 71) |

LDD-HIW (n = 522) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SE) | M(SE) | M(SE) | M(SE) | |

| Parent report | ||||

| Grade 4 externalizing | 55.69 (3.07)a | 50.82 (1.95) | 49.98 (1.52) | 48.95 (0.86) |

| Grade 5 externalizing | 54.11 (3.34)a | 51.40 (2.17) | 50.77 (2.07) | 47.22 (0.88) |

| Grade 7 CU trait | 0.57 (0.09) | 0.75 (0.06)a,b | 0.47 (0.06) | 0.44 (0.04) |

| Teacher report | ||||

| Grade 4 externalizing | 63.96 (2.84)a,b | 57.05 (1.88)a,b | 49.97 (1.58) | 51.31 (0.84) |

| Grade 5 externalizing | 60.03 (2.55)a,b | 59.48 (2.48)a,b | 53.25 (1.83) | 51.85 (0.98) |

Significantly different from LDD-HIW group at 0.05 level using the Wald χ2 test with 1 degree of freedom.

Significantly different from HSD-HIW group at 0.05 level using the Waldχ2 test with 1 degree of freedom.

Note HSD = high stable discipline. LIW = low increasing warmth. LDD = low decreasing discipline. HIW = high increasing warmth.

Discussion

Parenting is multifaceted and changes across development; however, the conventional strategy to measuring parenting uses a variable-centered approach. The current study aimed to capture parenting as a multidimensional and dynamic construct by identifying developmental patterns of PW and HD from kindergarten to grade 2 using a person-oriented approach with multi-informant measures of parenting and child outcomes in an ethnically diverse sample of families. Similar to prior longitudinal studies (e.g., Pettit et al. 2007; Shanahan et al. 2007a, 2007b; Simon et al. 2001), as opposed to being a static construct that remains stable, PW and HD both demonstrated a developmental pattern of change: In general, PW increased whereas HD decreased. These findings support the claim that parenting should be examined longitudinally as a dynamic construct, the change of which could inform the development of child outcomes (Pardini 2008; Pettit and Arsiwalla 2008).

Current findings also revealed inter-individual differences in developmental trajectories of the parenting dimensions. HD for some parents remained high and stable over time, and levels of PW at kindergarten differed substantially between parents. More specifically, similar to some prior studies that employed a person-oriented approach and primarily focused on parental monitoring (e.g., Laird et al. 2009; Luyckx et al. 2011; Van Ryzin and Dishion 2012) and parent-child warmth and conflict (e.g., Shanahan et al. 2007a, 2007b; Trentacosta et al. 2011) in middle childhood and adolescence, we found evidence for homogenous subgroups of parents who demonstrated similar developmental patterns of parenting with regard to HD (i.e., decreasing vs. stable) and PW (i.e., high vs. low). It is important to note that with regard to HD, despite a relatively higher level than the LDD group, parents of the HSD group nevertheless had low absolute levels, rarely endorsing any harsh discipline. Therefore, the interpretation of developmental patterns of parenting should be understood relative to identified subgroups themselves. These findings suggest that the levels of HD and PW in early childhood, possibly before kindergarten, have important implications for how these trajectories will develop over time, and also suggest that early intervention focusing on parenting for at-risk families before school entry might be especially warranted when disparities in HD and PW are already apparent.

More importantly, when considering HD and PW jointly as multidimensional aspects of parenting, most parents demonstrated the relatively normative developmental pattern of LDD- HIW (67%), whereas the relatively problematic pattern of HSD-LIW was the smallest (6.8%). Together the two subgroups included approximately 74% of the sample. This finding indicates that HD and PW are not independent from each other, and supports their negative association reported in previous studies (e.g., Pardini et al. 2007; Waller et al. 2015). However, a substantial portion of parents were also discordant regarding HD and PW. The LDD-LIW group (15.8%) possibly reflects a relatively neglectful or inconsistent pattern of parenting where parents provided low warmth and discipline, whereas the HSD-HIW pattern (10.4%) might represent an authoritative type of group of parents who would show their children warmth but would also administer harsh discipline in certain situations. Together, these results show that parents demonstrate different parenting patterns or styles (Baumrind 1991; Darling and Steinberg 1993; Power 2013), and demonstrate the unique benefit of a person-oriented approach to capturing these subgroups of parenting as a multidimensional construct with complex and dynamic developmental patterns, rather than along continuous scales.

Extant research has linked parenting with various variables at multiple levels involving parent (e.g., parenting efficacy and satisfaction, parental depression; Belsky 1984; Downey and Coyne 1990), family (e.g., SES; Dodge et al. 1994), and neighborhood (e.g., neighborhood safety; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000). The findings that neither parenting satisfaction nor parental depression predicted group membership in either PW or HD but did so in their joint patterns further illustrate the benefit of a person-oriented approach to capturing the unique combinations of multiple dimensions of parenting. Specifically, parents with lower parenting satisfaction were more likely to be in the LDD-LIW group relative to the LDD-HIW group, whereas parents with higher depressive symptoms were at higher risk of being in the HSD-LIW group relative to any of the three other groups. These results suggest that low parenting satisfaction and high depressive symptoms put parents at higher risk of demonstrating certain problematic patterns of parenting that could possibly lead to later negative child outcomes (Belsky 1984; Downey and Coyne 1990). In addition, SES and neighborhood safety generally predicted the group membership of problematic patterns relative to the normative LDD-HIW group. These results further consolidate the general finding that family and neighborhood disadvantages can affect child outcomes through their influences on parenting (Dodge et al. 1994; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000), and illustrate the importance of examining ecological contexts in which children develop to identify risks at multiple levels (Lanza and Rhoades 2013; Lanza et al. 2010).

Prior studies have shown that high HD and low PW are associated with elevated levels of child externalizing problems (Deater-Deckard et al. 1996; Rothbaum and Weisz 1994) and CU traits (Pasalich et al. 2016; Waller et al. 2013). Studies using a person-oriented approach to parenting generally found that relatively positive developmental patterns of parental monitoring (e.g., high and increasing) (e.g., Luyckx et al. 2011; Tobler and Komro 2010; Van Ryzin and Dishion 2012) and low levels of mother-son conflict (e.g., Trentacosta et al. 2011) were associated with better adolescent outcomes. Similarly, our findings demonstrated that different developmental patterns of HD and PW were associated with different child outcomes. Results from each parenting dimension alone suggest that low levels of PW were more closely associated with child externalizing problems, especially teacher-reports, and CU traits. The association between PW and CU traits is in line with prior results from a study (Pasalich et al. 2016) that used a subset of the sample in the study. While the associations of HD alone with child outcomes were not apparent, its effects appeared when combined with PW subgroups. Specifically, the relatively normative pattern of LDD-HIW was associated with the most optimal child outcomes, whereas the relatively problematic pattern HSD-LIW was associated with poorer child outcomes, notably regarding parent- and teacher-reported externalizing problems in grades 4 and 5. Thus, our findings are congruent with those reported by Luyckx et al. (2011), who found that children in the group demonstrating good parenting on multiple dimensions (monitoring, positive parenting, and inconsistent discipline) showed the least externalizing problems and substance use.

For teacher reports, children in the LDD-LIW group also demonstrated more externalizing problems in grades 4 and 5 than children in the HSD-HIW and LDD-HIW groups. This finding suggests that in addition to children of the relatively problematic HSD-LIW group, children in the LDD-LIW group may also face the risk of developing negative outcomes, especially given that children in this group also had the highest levels of CU traits in grade 7. It seems that, at least in the current sample for teacher reports, both groups that had the HIW pattern demonstrated low levels of externalizing problems, whether they showed HSD or LDD pattern regarding HD. Therefore, as reported previously (Deater-Deckard and Dodge 1997; McKee et al. 2007), high levels of PW seems to reduce the negative effect of HD on externalizing problems. However, children in the LIW group showed the worst externalizing problems for both parent and teacher reports when combined with HSD. Thus, one dimension of parenting may augment (LIW and HSD) or ameliorate (HIW over HSD) the effects of another. These findings also suggest the highly interactive and synergistic effects of multiple parenting dimensions in influencing child outcomes, and again demonstrate the benefits of a person-oriented approach to parenting.

Notable strengths of this study include the use of multi-informant measures of parenting (parent- and observer-reported) and child externalizing problems (parent- and teacher-reported) that provided the opportunity to capture their unique variance. Furthermore, the sample included families from diverse ethnic backgrounds, which enhances the generalizability of the results. It is important to note, however, that Cronbach’s α for HD was relatively low compared to other measures, which was possibly due to its smaller potential range and generally low levels in the sample. Future studies could consider jointly using other measurement instruments (e.g., Parent- Child Conflict Tactics Scale; Straus et al. 1998) to better tap into this construct. Additionally, future research employing a person-oriented approach should also include other dimensions of parenting (e.g., inconsistent parenting) during early and middle childhood.

Implications for Parenting Research and Prevention Science

Our results highlight the value of adopting a person-oriented approach to capture the multidimensional and dynamic nature of parenting. In contrast to the conventional variable-oriented approach to assessing parenting along continuous dimensions, a person-oriented approach assesses subgroups of parents that demonstrate different parenting patterns that are predicted by different variables at multiple levels and associated with different child outcomes. The prediction of different parenting patterns by various parent, family, and neighborhood variables suggests potential targets for family-centered interventions that aim to influence parenting to improve child developmental outcomes. Identifying subgroups in the population could inform future tailored and personalized interventions to better allocate limited resources and to achieve optimal outcomes by maximizing the fit between individuals and the type and dosage of intervention programs. Specifically, parents who have elevated levels of depressive symptoms and low levels of parental satisfaction (and are therefore at increased risk for developing high stable HD and low PW) may benefit from targeted preventive interventions that aim to reduce or prevent these risk factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement.

This article used data from the Fast Track project (for additional information about Fast Track, see http://www.fasttrackproject.org). We are grateful for the collaboration of the Durham Public Schools, the Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, the Bellefonte Area Schools, the Tyrone Area Schools, the Mifflin County Schools, the Highline Public Schools, and the Seattle Public Schools. We appreciate the hard work and dedication of the many staff members who implemented the project, collected the evaluation data, and assisted with data management and analyses. We are grateful to the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (Karen L. Bierman, John D. Coie, Kenneth A. Dodge, Mark T. Greenberg, John E. Lochman, Robert J. McMahon, and Ellen E. Pinderhughes) for providing the data and for additional involvement.

Funding. This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grants R18 MH48043, R18 MH50951, R18 MH50952, R18 MH50953, K05MH00797, and K05MH01027; National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grants DA016903, K05DA15226, and P30DA023026; and Department of Education Grant S184U30002. The Center for Substance Abuse Prevention also provided support through a memorandum of agreement with the NIMH. Additional support for the preparation of this work was provided by a LEEF B.C. Leadership Chair award, Child & Family Research Institute Investigator Salary and Investigator Establishment Awards, and a Canada Foundation for Innovation award to Robert J. McMahon.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991a). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (1991b). Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Reifman AS, Farrell MP, & Dintcheff BA (2000). The effects of parenting on the development of adolescent alcohol misuse: A six-wave latent growth model. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D (1991). Parenting styles and adolescent development In Brooks-Gunn J, Lerner R, & Petersen AC (Eds.), The encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 746–758). New York: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1990). Family Information Form. Available from the Fast Track Project website: http://www.fasttrackproiect.org.

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1991). Neighborhood Questionnaire. Available from the Fast Track Project website: http://www.fasttrackproiect.org.

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1992). A developmental and clinical model for the prevention of conduct disorder: The FAST Track Program. Development and Psychopathology, 4, 509–527. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2000). Merging universal and indicated prevention programs: The Fast Track model. Addictive Behaviors, 25, 913–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K, & Greenberg M (1990). Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development, 61, 1628–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, & Steinberg L (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, & Dodge KA (1997). Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry, 8, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (1996). Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (1990). Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science, 250, 1678–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, & Bates JE (1994). Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development, 65, 649–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G., & Coyne JC. (1990). Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 50–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, & Hare RD (2001). The Antisocial Process Screening Device. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell A, Keenan K, Kasza K, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, & Bean T (2008). Reciprocal influences between girls’ conduct problems and depression, and parental punishment and warmth: A six year prospective analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 663–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB (1975). Four Factor Index of Social Status Unpublished manuscript. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, & Mash EJ (1989). A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Dodge KA, Foster EM, Nix R, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2002). Early identification of children at risk for costly mental health service use. Prevention Science, 3, 247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Criss MM, Pettit GS, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2009). Developmental trajectories and antecedents of distal parental supervision. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29, 258–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, & Rhoades BL (2013). Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prevention Science, 14, 157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Rhoades BL, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2010). Modeling the interplay of multilevel risk factors for future academic and behavior problems: A person-centered approach. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 313–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, & Brooks-Gunn J (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 309–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, & Rubin DB (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Tildesley EA, Soenens B, Andrews JA, Hampson SE, Peterson M, & Duriez B (2011). Parenting and trajectories of children’s maladaptive behaviors: A 12- year prospective community study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 468–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K (1992). Warmth as a developmental construct: An evolutionary analysis. Child Development, 63, 753–773. [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Roland E, Coffelt N, Olson A, Forehand R, Massari C, ... & Zens MS. (2007). Harsh discipline and child problem behaviors: The roles of positive parenting and gender. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Witkiewitz K, Kotler JS, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2010). Predictive validity of callous-unemotional traits measures in early adolescence with respect to multiple antisocial outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 752–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL., Asparouhov T., & Muthen BO. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA (2008). Novel insights into longstanding theories of bidirectional parent-child influences: Introduction to the Special Section. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 627–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, Lochman JE, & Powell N (2007). The development of callous-unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: Are there shared and/or unique predictors? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 319–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich DS, Witkiewitz K, McMahon RJ, Pinderhughes EE, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2016). Indirect effects of the Fast Track intervention on conduct disorder symptoms and callous-unemotional traits: Distinct pathways involving discipline and warmth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 587–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, & Dishion TJ (1992). Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS., & Arsiwalla DD. (2008). Commentary on Special Section on “bidirectional parent-child relationships”: The continuing evolution of dynamic, transactional models of parenting and youth behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Keiley MK, Laird RD, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2007). Predicting the developmental course of mother-reported monitoring across childhood and adolescence from early proactive parenting, child temperament, and parents’ worries. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 206–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TG (2013). Parenting dimensions and styles: A brief history and recommendations for future research. Childhood Obesity, 9(s1), S-14–S-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinzie P, Onghena P, & Hellinckx W (2006). A cohort-sequential multivariate latent growth curve analysis of normative CBCL aggressive and delinquent problem behavior: Associations with harsh discipline and gender. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 444–459. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, & Weisz JR (1994). Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 55–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB, & Little RJ (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I., Schoenfelder E., Wolchik S., & MacKinnon D. (2011). Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 299–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, McHale SM, Crouter AC, & Osgood DW (2007a). Warmth with mothers and fathers from middle childhood to late adolescence: within-and between-families comparisons. Developmental Psychology, 43, 551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, McHale SM, Osgood DW, & Crouter AC (2007b). Conflict frequency with mothers and fathers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Within-and between-families comparisons. Developmental Psychology, 43, 539–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Chao W, Conger RD, & Elder GH (2001). Quality of parenting as mediator of the effect of childhood defiance on adolescent friendship choices and delinquency: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, & Runyan D (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22, 249–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler AL, & Komro KA (2010). Trajectories of parental monitoring and communication and effects on drug use among urban young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, 560–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Criss MM, Shaw DS, Lacourse E, Hyde LW, & Dishion TJ (2011). Antecedents and outcomes of joint trajectories of mother-son conflict and warmth during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 82, 1676–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2012). The impact of a family-centered intervention on the ecology of adolescent antisocial behavior: Modeling developmental sequelae and trajectories during adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 24, 1139–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, & McCrory EJ (2012). Why should we care about measuring callous-unemotional traits in children? British Journal of Psychiatry, 200, 177–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, & Hyde LW (2013). What are the associations between parenting, callous-unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, & Hyde LW (2015). Callous-unemotional behavior and early-childhood onset of behavior problems: The role of parental harshness and warmth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.