Abstract

Objectives

We tested how variations of the warning message on e-cigarette packages influenced risk and ambiguity perceptions, and whether including a modified risk statement on the package influenced how the warning label was perceived.

Method

A 4 (warning text) × 2 (modified risk statement), plus control, experiment (N = 451) was conducted.

Results

Smoking status, sex, and the language used in the warning statements interacted to influence risk perceptions. For example, non-smoking women perceived e-cigarettes with the FDA text at 30% of the package as riskier than the FDA text at 12-point type. Additionally, including a modified risk statement on the package increased ambiguity among non-smokers, as did an abstract warning label.

Conclusions

When evaluating the effectiveness of warning label text, it is important to consider smoking status and sex. Additionally, including modified risk statements on the package with the warning label could potentially increase ambiguity among non-smokers.

Keywords: e-cigarettes, warning labels, modified risk statements

Although electronic cigarettes have been used to help smokers stop using traditional cigarettes,1–3 recreation use or use for purposes other than cessation, has come to public attention in recent years because of data reporting increased use among teenagers, including never-smokers.4–6 The debate as to whether e-cigarettes represent a harm reduction strategy or a threat to tobacco control is multifaceted.7–9

On the harm reduction side, there is general agreement that e-cigarettes present substantially less of a health risk than traditional cigarettes.8 This is not inconsequential, as there are close to a half million tobacco-related deaths in the United States (US) each year, and reducing them is an important public health initiative.10 Prior research also has noted that cessation efforts through reduced harm products can be more effective if they are supported by a belief that the product is actually associated with lower health risks.11

Supporting the viewpoint that e-cigarettes represent a threat to tobacco control, scholars have noted simultaneous use of multiple tobacco products by individuals seeking cessation,6,9,12 lower than expected levels of sustained or exclusive use among daily smokers,9,13 the unknown long-term health effects from chronic use of e-cigarettes, concern for the developing adolescent brain,4 and the increase in uptake among adolescents and the potential gateway to cigarette smoking.5 However, whereas teen usage data have shown that e-cigarettes are associated with an increased likelihood of trying traditional cigarettes,4,5 scholars have cautioned against viewing these data as gateway effects, pointing out that only correlative conclusions are appropriate, that these statistics do not differentiate trial from sustained use, and that other factors influence which kids are most likely to try e-cigarettes, including the same risk factors for uptake of traditional cigarettes.8

This issue is complex.7,9,14 Indeed, some studies have shown that e-cigarettes facilitate quitting traditional cigarettes, but others have shown they hinder cessation.9,14 Whereas the extent to which e-cigarettes may be harm-reducing or harm-elevating is disputed, e-cigarettes can be thought of as potentially harm-reducing for traditional cigarette smokers and harm-elevating for non-tobacco users.4 The purpose of this work is to determine which type of health warning messages most effectively conveys risk, and to test whether adding a modified risk statement increases ambiguity in response to the package.

This inquiry is particularly timely. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finalized a rule in 2016 that extends the agency's regulatory authority to e-cigarettes, making it possible to require warning labeling on the product.15 The FDA faced legal opposition to its proposed graphic warning labels for traditional cigarette packages, and the decisions made on e-cigarettes could possibly face legal scrutiny as well. Specifically, the FDA may need to justify its proposed warning label: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical.15 Additionally, an e-cigarette manufacturer can file an application and substantiate claims that its product is a modified risk tobacco product, and if approved, market it accordingly.16 For example, a manufacturer may seek to add text stating its product has a lower risk of tobacco-related disease than traditional cigarettes to the packages.16 Therefore, it is important to know the impact of including modified risk messages on packages.

There has been a great deal of research conducted on health warning labels for traditional cigarette packages, including investigations into the effectiveness of graphic warning labels17–19 and plain packaging with pictorial warnings.20 For example, previous work has shown that pictorial labels for traditional cigarettes are more effective than text-based labels at increasing risk and harm perceptions, recall, attention to the warnings, and fear.21–27 Tat said, because the health risks associated with e-cigarettes, as well as the existing knowledge base surrounding those risks, are different than for traditional cigarettes,28,29 it is important to consider research specific to e-cigarette labeling.

E-cigarette Labeling and Risk Perceptions

To date, considerably less research has been conducted on e-cigarette labeling. To date, research has found limited or nuanced effects regarding the ability of warning labels to influence risk perceptions of e-cigarettes. For example, in one study, there was no difference in how risky e-cigarettes were perceived (perceived harm, addictiveness) following exposure to an e-cigarette advertisement with warning statements (manufacturer warnings and statement on the addictiveness of nicotine) compared to the advertisement without the warning statements.30 In a study varying the warning statements on e-cigarette television advertisements, only those warning statements that focused on the negative aspects of the e-cigarette industry increased risk perceptions, whereas those that focused on the e-cigarette ingredients did not.31

Further evidence that the type of warning statement may matter was provided by a survey with youth that tested the relative effectiveness of gain-framed versus loss-framed e-cigarette prevention messages. The authors found that loss-framed messages, which are messages focused on the negative consequences of use, were preferred when the topic was related to health risks, addiction or being labeled as a smoker, and gain-framed messages, which are messages focused on the positive consequences of non-use, were preferred when the topic was financial.32 In this study, sex also influenced how risks were perceived, with women preferring loss-framed messages.32 Additionally, in a discrete choice experiment, participants preferred to select either e-cigarette packages with no warning statement or the ones with the most extensive warning statement from the European Commission.33 The authors explain that it is likely that the comprehensive warnings provided participants with reassurance that the participants already knew about the risks.

Finally, in a series of focus groups with e-cigarette users and non-users, existing warnings on Vuse and MarkTen products were found to influence risk perceptions in complex ways.34 Researchers found that participants responded strongly to the claims that e-liquids can be poisonous or contain toxins and to the claim that they were not a safe alternative to traditional cigarettes. However, the participants also found these claims to be exaggerated and misleading.

While sex has been shown to influence risk perceptions in numerous other contexts, with men more likely than women to take risks,35 research on this topic in the context of e-cigarette labeling is underexplored. In his theoretical model, Gustafson provides a number of reasons for differences between how men and women perceive risk, including sex structures that influence norms, values, and perspectives.36 The consequence of this is that a sex effect can be found, even when exposure to the warning message does not differ.36 Additionally, the way participants describe themselves as women or men (sex-related adjectives) can influence how they interpret uncertainty or conflicting information when making risk assessments.37 Therefore, it is likely that men and women will differ when making risk assessments about e-cigarettes.

Overall, the existing research provides a complex picture as to whether and how e-cigarette warning labels influence risk perceptions. The present research aims to address this complexity by investigating how factors such as the type of warning statement, smoking status, and the sex of the participant influence risk perceptions in response to e-cigarette warning labels. We tested 4 variations of warning text that are explained below.

Conflicting Information

Conflicting information refers to 2 or more claims within the same message or package that are discordant.38 There may be ambiguity in how the public views e-cigarettes due to conflicting messages regarding their role as a potential smoking cessation and harm reduction tool versus reports of increased recreational use with associated harm.1,2,4,8,28,39,40 As noted above, an e-cigarette manufacturer may apply to have its product designated a modified risk tobacco product.16 For example, it may claim and substantiate that the product is associated with lower tobacco-related disease than traditional cigarettes.16 However, if a modified risk statement stating this claim were added on the same package as the warning label, these 2 pieces of information would constitute conflicting information, which as noted above, could lead to confusion and ambiguity. There is some evidence that this would occur.

There has been extensive research on how conflicting information influences persuasion in branding and advertising,41–43 risk communication,44–46 and health information.38 However, to our knowledge, only one study has been conducted on the role of conflicting information regarding modified risk statements for e-cigarettes.47 In a series of focus groups, smokers and e-cigarette users were shown 2 different e-cigarette modified risk statements stylized as warning statements, following a study in which they considered e-cigarette warning labels.47 Participants reported that although the modified risk statements communicate that e-cigarettes are safer and include information they want to know, they did not appear to be true warnings, and the phrase substantially lower risks was deemed to be misleading and difficult to interpret.47

In a study considering modified risk statements and snus, current tobacco users reported lower harm perceptions and an increased likelihood of using the product; however, never smokers who viewed the modified risk statement that included the phrase substantially lower risks had higher purchasing intentions.48 Additionally, studies on brewer-sponsored, responsible drinking campaigns have demonstrated that conflicting information in the messages, including commercial content alongside specific warnings about unsafe drinking, were ambiguous, leading to misinterpretation of the messages.49,50 Therefore, we hypothesize that packages with a modified risk statement and a warning label are associated with greater ambiguity than packages without a modified risk statement and with just a warning label.

Methods

We conducted an online experiment with smokers and non-smokers exposed to different e-cigarette warning labels. Participants were randomly assigned to either view packages with a warning label or with a warning label and a modified risk statement.

Participants

First, we conducted a power analysis with G*Power 3.1 and selected a sample size that provided adequate power to detect a medium effect size. Participants were 462 Amazon Mechanical Turk workers who completed the study in May 2016. They were paid $2.00 each to complete the study. Only mTurk participants who were US-based and had completed at least 100 assignments with an 80% approval rate were eligible to do the study. Furthermore, we informed participants that they needed to be able to read and write English fluently, and we collected a writing sample from them. Overall, 450 participants reported that English was their first language, and 460 reported that they spoke English for over 10 years.

We excluded 11 participants from the study. Some participants (N = 7) were excluded for failing an attention check, which means that they inaccurately replied to a question stating: For this item, please select the answer Agree to indicate that you are paying attention. Additionally, we excluded some participants for a timing problem with the study (N = 4). The remaining 451 participants took an average of 11 minutes and 11 seconds to complete the study. They ranged in age from 18-72 years (M = 34.76, SD = 10.87). Among participants, 270 (60%) reported they were men, and 181 (40%) reported they were women. Additionally, 148 (33%) reported smoking traditional cigarettes within the past 30 days, and 110 (24%) reported using e-cigarettes within the past 30 days. Of the e-cigarette users, 35 (7.8%) participants reported not smoking traditional cigarettes in the past 30 days, and of these, only one person reported never smoking traditional cigarettes. Participants in the experimental conditions were randomly assigned to one of 8 conditions in the 4 (warning text) × 2 (modified risk statement), full-factorial experiment. We also randomly assigned 51 participants to a comparison control condition, and those participants did not view warning statements or modified risk statements. This control condition is used only as a comparison for the manipulation check, as the other measures are not informative when no warning statement is viewed.

Manipulations

Stimulus materials

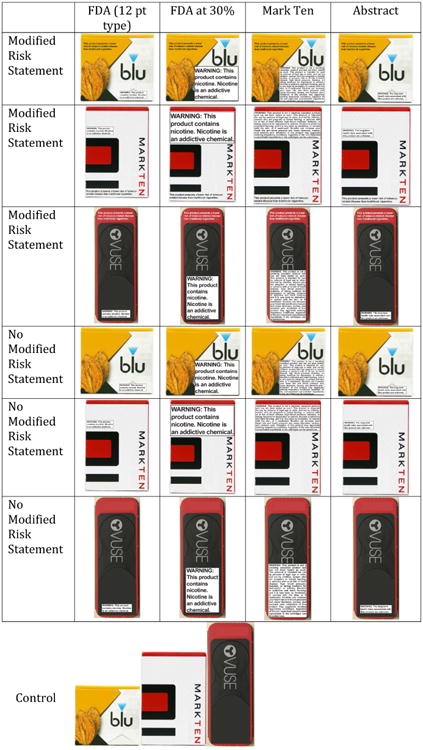

Participants viewed a series of images showing e-cigarette cartridge boxes (Figure 1). The packages included one of 4 warning labels (described further below). Half of the participants viewed images of the packages with a warning statement and without a modified risk statement, and the other half viewed images of packages with both a warning statement and a modified risk statement. Participants in the control condition viewed package fronts that did not contain a warning label or a modified risk statement. The box size, font, and style of the labels were standardized across conditions. Each participant viewed for 10 seconds each, 9 images of e-cigarette cartridge boxes representing 3 brands (3 of each brand). The e-cigarette brands used were ones launched by big tobacco companies: Vuse, Blu, and MarkTen, which together represent 66.5% of the brick-and-mortar market share in the US.51 The size of the boxes was screen-proportioned to appear optically at the sizes they would if they were held in one's hand.52

Figure 1. Stimuli by Warning Text Condition and Modified Risk Statement Condition.

Warning text

As noted above, the FDA deeming states that the packages must display the language: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical, and that this text should fill a box that is 30% of the size of the package using no less than 12-point type. If the FDA should need to defend its restriction on commercial speech, it may be necessary for them to show that this statement is more effective compared than others that might be proposed. In the public comments on the deeming, for example, comments questioned whether the warnings needed to be 30% of the package, or whether 12-point type might be sufficient.15 Therefore, it is useful to compare the FDA proposed text at 30% of package with the less restrictive FDA proposed text at 12-point type.

The manufacturer of MarkTen currently uses a 117-word warning that mentions several detailed health consequences associated with e-cigarette use, including the toxicity of nicotine and that ingestion of the cartridge contents can be poisonous. These consequences are also noted in the public comments on the deeming, and the FDA acknowledged the importance of this concern and an interest in data that “helps to inform regulatory actions with respect to nicotine exposure warnings.”15(p 59) Therefore, it is useful to compare the MarkTen warning to the FDA-approved text.

One critique of e-cigarette warning labels is that information about the long-term risks is still unknown, and therefore, it is difficult to measure the public health impact of their use.7 Prior research has shown that this influences how warning labels are interpreted.47 For example, in a focus group study on modified risk claims and e-cigarettes, participants expressed concern about strong reduced harm messages because actual risks of e-cigarettes are currently unknown.47 From a theoretical perspective, construal level theory would suggest that the more distant a health consequence, both temporally or in hypotheticality, the more abstractly we think about it.53 In other words, if health risks are unknown at this time, we will think about them more abstractly than if they are fully understood and easy to quantify. A more abstract warning (The long-term health risks associated with this product are unknown) would capture this uncertainty and can be thought of as a less extensive regulation than the FDA-approved warning. Therefore, it is useful to compare this abstract warning to the FDA-approved warning text and to set the abstract warning at the less restrictive 12-point type. Drawing upon these substantive examples, participants were randomly assigned to view one of 4 warning text conditions: (1) the FDA text at 12-point type; (2) the FDA text at 30% of package size, as proposed; (3) the MarkTen 117-word warning; or (4) the abstract warning mentioned above.

Modified risk statement

As noted, it is possible that an e-cigarette manufacturer could apply to have its product considered a modified risk tobacco product. For example, the manufacturer may be able to substantiate: This product presents a lower risk of tobacco-related disease than traditional cigarettes. Participants were randomly assigned to view packages with or without this sample modified risk statement, and this factor was fully-crossed with the warning text variations mentioned above.

Procedure

All participants completed the study online. They clicked on a link in Amazon Mechanical Turk that launched the study in Qualtrics. First, they responded to demographic and tobacco use questions. Next, they were randomly assigned by Qualtrics to receive one of the 8 warning label/modified risk statement conditions or the control condition, which did not include warning text or a modified risk statement. Participants viewed a short message that introduced the labels and provided instructions on reading them carefully. They were informed that they may see a package more than once. Next, they viewed 9 images (3 brands: Blu, Vuse, MarkTen, 3 times each) in their assigned condition. The images remained on the screen for a minimum of 10 seconds before participants had the option to advance the page. The number of images viewed and the amount of time they remained on-screen were selected to be consistent with prior literature on the FDA-proposed graphic warning labels.54 Following the presentation of the stimuli, participants completed dependent measures. They were debriefed.

Measures

Risk perceptions

To measure risk perceptions, a question was adapted from prior research.55 We asked participants: In your opinion, is using electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) risky for one's health? They responded on a 3-point scale (1 = not at all; 2 = maybe; 3 = yes), (N = 400, M = 2.45, SD = .57).

Ambiguity

To measure ambiguity perceptions, participants responded on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = very much) to 4 statements: the packages were confusing, the packages were contradictory, the packages were ambiguous, and I was confused by the packages I viewed.56 These items were averaged to form an ambiguity scale (N = 400, M = 2.28, SD = 1.37, α = .83).

Data Analysis

We used SPSS software version 22 (IBM, SPSS) to conduct the analyses. Data were summarized by means and standard deviations (SD) within subgroups defined by our factorial design. We related the conditions of interest against either a comparison (modified risk/ no modified risk condition) or control (warning label language/ control) on measures to test our experimental manipulations. Next, to investigate the effects of warning statement, sex, and smoking status on risk perceptions, we isolated only those participants who saw the warning label without a modified risk statement, entered these 3 factors as the independent variables and ran an ANOVA on the dependent variable of risk perceptions. For this full-factorial design, we used Tukey post hoc analyses and planned pairwise comparisons to determine main effects and interactions. For ambiguity perceptions, we split the data on smoking status and ran an ANOVA with sex, modified risk condition, and label condition entered as predictors, and the ambiguity scale entered as the dependent variable. Again, Tukey post hoc analyses and planned pairwise comparisons were used in this full-factorial design to establish significant main effects and interactions.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Modified risk statement

As a manipulation check for modified risk statement, participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale, (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree to the item, the products you viewed are associated with a lower risk of tobacco-related disease than traditional cigarettes. Participants in the modified risk statement condition (N = 201, M = 3.78, SD = .93) scored higher on this item than participants in the no modified risk statement condition (N = 199, M = 3.32, SD = 1.04), F (1, 399) = 21.77, p < .001, η2 = .05. Additionally, these strong findings hold for smokers, p < .001, and non-smokers, p = .005.

Warning label statement

As a manipulation check for warning label statement, participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale, (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree, to statements mentioned in their labeling condition. As expected, participants in the FDA warning statement conditions (N = 98, M = 4.69, SD = .49; N = 100, M = 4.82, SD = .39) agreed more than participants in the control condition (N = 51, M = 4.06, SD = .95) with the statement, the products you viewed contain nicotine, F(4, 244) = 15.79, p < .001, η2 = .21. Participants in the MarkTen warning statement conditions (N = 102, M = 4.35, SD = .78) agreed more than participants in the control condition (N = 51, M = 3.82, SD = .82) with the statement, the products you viewed can increase your heart-rate, F(2, 150) = 7.61, p = .001, η2 = .09. And, participants in the abstract warning statement condition (N = 100, M = 4.41, SD = .89) agreed more than participants in the control condition (N = 51, M = 3.71, SD = 1.22) with the statement, the long-term health risks associated with the products you viewed are unknown, F(2, 148) = 8.16, p = .001, η2 = .10.

Risk Perceptions

First, we tested whether the type of warning statement, smoking status, and the sex of the participant influence risk perceptions in response to e-cigarette warning labels. Isolating the analyses to only those participants who viewed a warning statement alone (without a modified risk statement), warning statement condition, smoking status, and sex were entered as the independent variables and risk perceptions was entered as the dependent variable into an ANOVA. Table 1 includes means, standard deviations, and significance of planned comparisons. There was a main effect for warning statement condition, F(3, 183) = 3.59, p = .02, η2 = .05, and smoking status, F(1, 183) = 12.36, p = .001, η2 = .05, and a 3-way interaction between all factors, F(3, 183) = 4.04, p = .008, η2 = .05. Therefore, risk perceptions varied based on which label was viewed, whether the participant was a smoker or not and the interaction of these 2 factors with sex.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations for Risk Perceptions – Label-Only Conditions.

| Label Condition (No Modified Risk Statement) | Sex | Smoking Status | Risk Perception M (SD) | Significance of Planned Comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA Text 12 Point | Men | Cigarette Smoker | 2.27 (.65) | *FDA12-pt,M,NCS |

| Not Cigarette Smoker | 2.79 (.43) | *FDA12-pt,M,CS, **FDA12-pt,W,NCS, **Abs,M,NCS | ||

|

|

||||

| Women | Cigarette Smoker | 2.33 (.82) | ||

| Not Cigarette Smoker | 2.25 (.68) | **FDA12-pt,M,NCS, *FDA30%,W,NCS, +MarkT,W,NCS | ||

|

|

||||

| FDA Text, 30% Pack | Men | Cigarette Smoker | 2.67 (.50) | *FDA30%,W,CS, **Abs,M,CS, *MarkT,M,CS |

| Not Cigarette Smoker | 2.58 (.61) | *Abs,M,NCS | ||

|

|

||||

| Women | Cigarette Smoker | 2.00 (.58) | *FDA30%,M,CS, **FDA30%,W,NCS, +MarkT,W,CS | |

| Not Cigarette Smoker | 2.67 (.62) | *FDA12-pt,W,NCS, **FDA30%,W,CS | ||

|

|

||||

| Abstract Warning | Men | Cigarette Smoker | 2.00 (.41) | **FDA30%,M,CS |

| Not Cigarette Smoker | 2.13 (.52) | **FDA12-pt,M,NCS, *FDA30%,M,NCS, *Abs,W,NCS **MarkT,M,NCS | ||

|

|

||||

| Women | Cigarette Smoker | 2.00 (.63) | *Abs,W,NCS, +MarkT,W,CS | |

| Not Cigarette Smoker | 2.56 (.51) | *Abs,M,NCS, *Abs,W,CS | ||

|

|

||||

| MarkTen Warning | Men | Cigarette Smoker | 2.17 (.39) | *FDA30%,M,CS, **MarkT,M,NCS |

| Not Cigarette Smoker | 2.74 (.45) | **Abs,M,NCS, **MarkT,M,CS | ||

|

|

||||

| Women | Cigarette Smoker | 2.57 (.54) | +FDA30%,W,CS, +Abs,W,CS | |

| Not Cigarette Smoker | 2.64 (.50) | +FDA12-pt,W,NCS | ||

Note.

FDA 12-pt = FDA text 12 point; FDA 30% = FDA text 30% of pack; Abs = Abstract Warning; MarkT = MarkTen Warning

M = Men; W = Women

CS = cigarette smoker; NCS = Not Cigarette Smoker

Asterisks denote statistically significant differences: ns = non-significant;

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

The last column identifies which conditions differ from the condition identified in the row. For example, in the first row, male, smokers who viewed the FDA text at 12-point were significantly different (p < .05) than male, non-smokers who viewed that same label.

Raw means are reported in Table 1. Significant differences are based on the least squares means.

First, there was a main effect for warning statement condition on risk perceptions. Participants who viewed the MarkTen text (N = 52, M = 2.56, SD = .50) and the FDA text at 30% of package (N = 50, M = 2.54, SD = .61) reported significantly higher risk perceptions than participants who viewed the abstract warning statement condition (N = 50, M = 2.22, SD = .55), p = .01 and p = .02, respectively. Participants who viewed the FDA warning text at 12-point type were in the middle, (N = 47, M = 2.43, SD = .65), but did not differ significantly from the other conditions. Therefore, the FDA text at 30% of package and the MarkTen text resulted in higher levels of risk perceptions.

Non-smokers

Overall, non-smokers (N = 128, M = 2.55, SD = .57) perceived e-cigarettes as riskier than smokers did (N = 71, M = 2.24, SD = .57), and this was particularly true for non-smoking men (compared to smoking men) who viewed the FDA text at 12-point (p = .02) and those who viewed the MarkTen text (p = .005) and for non-smoking women (compared to smoking women) who viewed the FDA text at 30% of package (p = .008) and those who viewed the abstract text (p = .03). Non-smoking women who viewed the FDA text at 30% of package perceived e-cigarettes as riskier than those who viewed the FDA text in 12-point font (p = .035). Non-smoking men who viewed the abstract warning text perceived e-cigarettes as less risky than non-smoking men in the other warning statement conditions (FDA text at 12-point: p = .002; FDA text at 30% of package: p = .02; Mark-Ten text: p = .002). The abstract warning text was interpreted differently by non-smoking men and women (p = .03) with it reducing risk perceptions in the case of non-smoking men and increasing risk perceptions in the case of non-smoking women.

Smokers

Smoking men who viewed the FDA-proposed text at 30% of package perceived e-cigarettes as riskier than did smoking men who viewed the MarkTen text (p = .04) or smoking men who viewed the abstract text (p = .005). Among smoking women, there were no significant differences in how the different label conditions were perceived.

Overall, warning statement, sex, and smoking status influenced risk perceptions, with the abstract text eliciting lower risk perceptions among non-smoking men, but not among women and with the FDA proposed text at 30% of package conveying greater risks than the same text at a smaller size among non-smoking women.

Ambiguity Perceptions

As mentioned above, we predicted that participants who viewed e-cigarette warning labels with a modified risk statement would report higher levels of ambiguity than participants who viewed the labels without a modified risk statement. Splitting the data on smoking status, an ANOVA was conducted with sex, modified risk condition, and label condition entered as predictors and the ambiguity scale entered as the dependent variable. Table 2 includes means, standard deviations, and significance of planned comparisons. As predicted, among non-smokers, participants who viewed the warning label with a modified risk statement (N = 135, M = 2.64, SD = 1.48) reported higher levels of ambiguity than those who did not view the modified risk statement (N = 128, M = 1.81, SD = 1.17), F(1, 247) = 26.63, p < .001, η2 = .09. This effect was not found among smokers.

Table 2. Means and Standard Deviations for Ambiguity Perceptions – Split by Smoking Status.

| Sex | Modified Risk Condition | Label Condition | Ambiguity Scale - Cigarette Smokers M (SD) | Ambiguity Scale (Not Cigarette Smokers) M (SD) | Significance of Planned Comparisons (non-smokers) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | No Modified Risk | FDA Text at 12-pt | 2.61 (1.23) | 1.71 (.82) | |

| FDA Text at 30% of pack | 2.00 (1.42) | 1.37 (.63) | *M, NMR, Abs, *M, MR, FDA 30% | ||

| Abstract Text | 2.56 (1.19) | 2.38 (1.69) | *M, NMR, FDA 30%, +M, MR, Abs | ||

| Mark Ten Text | 2.46 (1.11) | 1.64 (.95) | *M, MR, MarkT | ||

| Modified Risk | FDA Text at 12-pt | 2.07 (1.12) | 2.01 (1.36) | **M, MR, Abs, **W, MR, FDA 12-pt | |

| FDA Text at 30% of pack | 2.40 (.80) | 2.40 (.92) | *M, MR, Abs, *M, NMR, FDA 30% | ||

| Abstract Text | 2.55 (1.70) | 3.28 (1.46) | **M, MR, FDA 12-pt, *M, MR, FDA 30%, +M, MR, MarkT, +M, NMR, Abs | ||

| Mark Ten Text | 3.44 (1.36) | 2.58 (1.26) | +M, MR, Abs, *M, NMR, MarkT | ||

| Women | No Modified Risk | FDA Text at 12-pt | 1.71 (.84) | 2.13 (1.46) | *W, MR, FDA 12-pt |

| FDA Text at 30% of pack | 1.36 (.63) | 1.83 (1.44) | |||

| Abstract Text | 1.79 (1.08) | 2.08 (1.16) | +W, MR, Abs | ||

| Mark Ten Text | 2.46 (2.02) | 1.43 (.70) | *W, MR, MarkT | ||

| Modified Risk | FDA Text at 12-pt | 2.25 (.54) | 3.32 (2.09) | *W, MR, FDA 30%, **M, MR, FDA 12-pt, *W, NMR, FDA 12-pt | |

| FDA Text at 30% of pack | 2.11 (.84) | 2.25 (1.07) | *W, MR, FDA 12-pt | ||

| Abstract Text | 3.00 (2.22) | 3.05 (1.48) | +W, NMR, Abs | ||

| Mark Ten Text | 2.61 (1.09) | 2.55 (2.06) | *W, NMR, MarkT |

Note.

M = Men; W = Women

NMR = no modified risk; MR = modified risk

FDA-12pt = FDA text 12-point; FDA 30% = FDA text 30% of pack; Abs = Abstract Warning; MarkT = MarkTen Warning

Asterisks denote statistically significant differences: ns = non-significant;

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

In Table 2, we only report significant differences within non-smokers. However, one significant difference (p<.05) was found within smokers: males who viewed the FDA text at 12-point with a modified risk statement differed from males who viewed the MarkTen label with a modified risk statement.

Raw means are reported in Table 2. Significant differences are based on least squares means.

There was also a main effect for warning statement text among non-smokers, F(3, 247) = 3.78, p = .01, η2 = .04, with participants in the abstract warning label condition (N = 60, M = 2.70, SD = 1.51) reporting higher ambiguity perceptions. Specifically, they reported higher ambiguity perceptions than participants who viewed the FDA text at 30% of package (N = 70, M = 1.96, SD = 1.09), p = .009, and those who viewed the MarkTen text (N = 67, M = 2.07, SD = 1.34), p = .038.

Discussion

Review of Findings

Risk perceptions

We tested whether varying the warning statement on an e-cigarette cartridge package would influence risk perceptions. The findings reflect a main effect for smoking status, such that non-smokers report higher risk perceptions than smokers in response to the warning statements. It is likely that participants are responding based on their own comparison anchors, with smokers juxtaposing with traditional cigarette use and non-smokers comparing e-cigarettes to not using tobacco at all.

There was also a main effect for warning label condition, regardless of smoking status and sex. Participants who viewed either the MarkTen text or the FDA proposed text at 30% of package reported higher risk perceptions than those who viewed the abstract text, while those who viewed the FDA-approved warning text at 12-point type were in the middle. One inquiry to consider is why the FDA-approved warning text at the larger size with larger text did not yield higher risk perceptions than the FDA-approved warning text at the smaller size with 12-point text. First, it is important to note, as will be discussed further below, that this finding did emerge among non-smoking women, and therefore, it is possible that the greater number of men than women in our study prevented detection of the overall difference. It is also worth noting that the means were in the expected direction, so one possibility is that the effect size was too small or that the risk perception measure used did not include enough variability in the scale.

Our results also showed an interaction among warning label condition, sex, and smoking status. Whereas non-smoking men reported lower risk perceptions after exposure to the abstract text, women, including non-smoking women, did not. Prior research has considered how men and women differ regarding risk perceptions, with women reporting greater certainty in their perception that something is risky.57–59 Therefore, it is possible that women perceived the abstract warning statement, which expressed unknown health risks, as certain that risks existed, even if they were unknown at present.

As mentioned above, non-smoking women perceived the FDA required text at 30% of package as conveying greater risks than the same text in a smaller warning box at 12-point font. Additionally, smoking men who viewed the FDA proposed text at 30% of package perceived e-cigarettes as riskier than those who viewed the MarkTen text and the abstract text, but not those who viewed the smaller FDA text. As noted above, in a prior study on e-cigarettes, it was found that warning labels that mentioned e-cigarette ingredients did not increase risk perceptions;31 however, in this study, the FDA proposed text at 30% of package, which mentions the product ingredient nicotine, generated higher ratings of risk perceptions among non-smoking women and smoking men.

It also was mentioned above that in a prior study about e-cigarette warning labels, loss-framed messages were particularly effective among women.32 Whereas this study was not designed specifically to test gain-framed versus loss-framed messages, non-smoking women did report higher risk perceptions than non-smoking men following exposure to the abstract text, which featured a message that can be thought of as a loss-framed appeal, as it focuses on unknown health consequences of e-cigarette use.

Ambiguity perceptions

Our study established that adding a modified risk statement to the e-cigarette cartridge packages can lead to ambiguity among non-smokers. Specifically, among non-smokers, packages that included a modified risk statement and packages with the abstract warning statement were seen as more ambiguous than packages without a modified risk statement and packages with other warning statements, respectively. Smokers did not differ in their ambiguity ratings based on condition. It is possible that this is because they did not perceive the nicotine in the e-cigarettes to be as addictive as their usual brand of traditional cigarettes.

Limitation and Future Research

It is essential to clarify some limitations of this project and to articulate some key areas that future research might address. This study was conducted online with an mTurk, adult participant pool. Although this recruitment strategy facilitated the collection of data from both smokers and non-smokers, it is essential that future research is conducted with teenagers. According to the 2015 National Youth Tobacco Survey, 25.3% of high school students report tobacco product use, with the majority (16%, 3 million high school students) reporting use of e-cigarettes at least once in the past 30 days.60 Additionally, it is important to test different types of exposure to the warning message, including a longer duration, repeated viewing, and point-of-purchase.

Many of the procedures and measures in this study have been validated in prior research. That said, we fully recognize that the concepts we are studying can be researched in different ways. For example, our risk perception measure featured a 3-point scale, and it may have been more informative to use a scale that facilitated a greater range.

We randomly assigned participants to conditions, with the assumption that factors such as sex, smoking status, and e-cigarette usage would be spread evenly across conditions as a function of random assignment. For the most part, this worked as intended, and these sociodemographic factors were represented in all conditions and spread pretty evenly (although not perfectly) across conditions. There were about 12-13 participants who were e-cigarette users in most conditions. However, there were a few additional traditional smokers and e-cigarette users in the abstract warning label-modified risk statement condition, and this is probably because there was a slightly higher number of men in this condition as well. There were fewer e-cigarette users in the FDA warning label at 30% of package size-no modified risk statement condition and the FDA warning label at 12-point type-modified risk statement condition, and these were primarily traditional cigarette smokers. Future research may consider whether segmenting the sample by sex and tobacco use status would be useful.

Furthermore, we did not measure or control for other individual difference factors, including prior knowledge about the risks of e-cigarettes, trait reactance, or sensation seeking, and these can be investigated in future research.61 We also did not measure whether or not participants held any misperceptions associated with nicotine.62 Prior research has indicated that people sometimes have uncertainty over whether or not nicotine causes cancer, and this could influence how reduced harm products are perceived by smokers.63 Therefore, future research should consider how nicotine misperceptions influence risk perceptions associated with warning labels and modified risk statements.

Additionally, we selected to include the abstract warning text at 12-point type, rather than 30% of the box. We viewed the abstract text condition as a less restrictive infringement on commercial speech rights than the other conditions, and therefore, we wanted to be able to compare it to the less restrictive version of the FDA warning statement condition (12-point type). However, one might argue it could be more informative to test this condition at 30% of package size, and this can be tested in future research. Future research also should test how other types of conflicting information on the packages, such as novelty favors, influence responses to the warning messages.

Implications for Tobacco Regulation

Authors of a theoretical taxonomy of conflicting information have argued that it is essential to research particular substantive domains directly.38 As mentioned previously, to our knowledge, little research has been conducted on e-cigarette labeling in regards to conflicting information, such as a modified risk statement.47

As the FDA begins to enforce which language is required and what is permitted on e-cigarette packages, social scientific research can provide guidance. For example, our study demonstrated that abstract warning labels led to lower risk perceptions than other warning labels, specifically among non-smoking men. Among non-smoking women, the FDA warning at the required 30% of package size was more effective at generating risk perceptions than the same text in a smaller proportional size. This finding supports the view that the FDA warning at 30% of package might be appropriate, as it increases risk perceptions among non-smoking women.

Furthermore, whereas smoking men, who may consider e-cigarettes as a possible cessation or harm reduction tool, expressed higher risk perceptions after viewing the FDA text at 30% of package than they did in the Mark-Ten and the abstract warning text conditions, there were no differences in risk perceptions regardless of whether the FDA text was large or small, so it does not appear the increased size deters use among those who could consider e-cigarettes a cessation tool. On the other hand, as the FDA-approved warning text will be placed on small packages, including e-cigarette liquids, it may often appear at a physically small size. Therefore, it is helpful to know that the statement can influence risk perceptions at both large and small sizes.

A practical recommendation emerged regarding modified risk statements. The application for including a modified risk statement on an e-cigarette product is likely to be made on the premise that the statement can help draw smokers away from traditional, more toxic cigarettes, and our manipulation check indicates that a modified risk statement can foster the perception that e-cigarettes are associated with a lower risk of tobacco-related disease than traditional cigarettes. This finding suggests that modified risk statements may encourage smoking cessation. However, it is important to note that non-smokers also reported perceiving a lower risk of tobacco-related disease, as well as increased ambiguity perceptions, after viewing the packages with modified risk statements. The findings involving non-smokers are concerning, as the lower risk perception and increased ambiguity could similarly lower resistance to trying the product. Future research could test whether this is true, and explore the potential impacts of modified risk claims further.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this paper was supported in part, by the National Institutes of Health/ National Cancer Institute (U19 CA157345), by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (R03 DA043022), and by funds from the University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts and Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA/NIH, the FDA, or the University of Minnesota.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement: The Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota gave permission to collect data in May 2016.

Conflict of Interest Statement: There are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Sherri Jean Katz, Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Bruce Lindgren, Coordinator, Masonic Cancer Center Biostat Core, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Minnesota.

Dorothy Hatsukami, Tobacco Research Programs Director, Department of Psychiatry Professor, Associate Director of Cancer Prevention and Control, Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

References

- 1.Brown J, Beard E, Kotz D, et al. Real world effectiveness of e-cigarettes when used to aid smoking cessation: a cross-sectional population study. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1531–1540. doi: 10.1111/add.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS. Electronic cigarettes as a smoking-cessation tool: results from an online survey. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(4):472–475. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal College of Physicians. Nicotine without smoke: tobacco harm reduction. [Accessed June 24, 2017];2016 Available at: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction-0.

- 4.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students in the United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunnell R, Israel A, Apelberg B, et al. Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking U.S. middle and high school electronic cigarette users, National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):228–235. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilreath TD, Leventhal A, Barrington-Trimis JL, et al. Patterns of alternative tobacco product use: emergence of hookah and e-cigarettes as preferred products amongst youth. J Adolesc Heal. 2016;58(2):181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrams DB. Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete? JAMA. 2014;311(2):135–136. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozlowski LT, Warner KE. Adolescents and e-cigarettes: objects of concern may appear larger than they are. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;174:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bareham D, Ahmadi K, Elie M, Jones AW. E-cigarettes: controversies within the controversy. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(11):868–869. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. Center for tobacco products overview. [Accessed May 31, 2017]; Available at: https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/AboutCTP/ucm383225.htm.

- 11.Haddock CK, Lando H, Klesges RC, et al. Modified tobacco use and lifestyle change in risk-reducing beliefs about smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, et al. Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(1):79–89. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.958857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giovenco DP, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD. Factors associated with e-cigarette use: a national population survey of current and former smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):476–480. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall MG, Pepper JK, Morgan JC, Brewer NT. Social interactions as a source of information about e-cigarettes: a study of U.S. adult smokers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(8):788. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13080788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Health & Human Services and Food and Drug Administration. Deeming Tobacco Products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Control Act. [Accessed June 24, 2017];Fed Regist. 2016 81(90):28973–29106. Available at: http://webapps.dol.gov/federalregister/PdfDisplay.aspx?DocId=26927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. 111th United States Congress. [Accessed May 31, 2017];2009 Available at: http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr1256/text.

- 17.Trasher JF, Hammond D, Fong GT, Arillo-Santillán E. Smokers' reactions to cigarette package warnings with graphic imagery and with only text: a comparison between Mexico and Canada. Salud Publica Mex. 2007;49(Suppl 2):S233–S240. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342007000800013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, et al. Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: findings from the international tobacco control four country study. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(3):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A, et al. Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii19–iii25. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCool J, Webb L, Cameron LD, Hoek J. Graphic warning labels on plain cigarette packs: will they make a difference to adolescents? Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(8):1269–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bansal-Travers M, Hammond D, Smith P, Cummings KM. The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20(3):327–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond D, Fong GT, Zanna MP, et al. Tobacco denormalization and industry beliefs among smokers from four countries. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(3):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Hegarty M, Pederson LL, Nelson DE, et al. Reactions of young adult smokers to warning labels on cigarette packages. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(6):467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White V, Webster B, Wakefield M. Do graphic health warning labels have an impact on adolescents' smoking-related beliefs and behaviours? Addiction. 2008;103(9):1562–1571. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCool J, Webb L, Cameron LD, Hoek J. Graphic warning labels on plain cigarette packs: will they make a difference to adolescents? Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(8):1269–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider S, Gadinger M, Fischer A. Does the effect go up in smoke? A randomized controlled trial of pictorial warnings on cigarette packaging. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farsalinos KE, Polosa R. Safety evaluation and risk assessment of electronic cigarettes as tobacco cigarette substitutes: a systematic review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5(2):67–86. doi: 10.1177/2042098614524430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goniewicz ML, Lingas EO, Hajek P. Patterns of electronic cigarette use and user beliefs about their safety and benefits: an Internet survey. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(2):133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mays D, Smith C, Johnson AC, et al. An experimental study of the effects of electronic cigarette warnings on young adult nonsmokers' perceptions and behavioral intentions. Tob Induc Dis. 2016;14(17) doi: 10.1186/s12971-016-0083-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanders-Jackson A, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP, Henriksen L. Effect of warning statements in e-cigarette advertisements: an experiment with young adults in the United States. Addiction. 2015;110(12):2015–2024. doi: 10.1111/add.12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, et al. Preference for gain- or loss-framed electronic cigarette prevention messages. Addict Behav. 2016;62:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czoli CD, Goniewicz M, Islam T, et al. Consumer preferences for electronic cigarettes: results from a discrete choice experiment. Tob Control. 2016;25(e1):e30–e36. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wackowski OA, Hammond D, O'Connor RJ, et al. Smokers' and e-cigarette users' perceptions about e-cigarette warning statements. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(7) doi: 10.3390/ijerph13070655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Byrnes JP, Miller DC, Schafer WD. Sex differences in risk taking: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(3):367–383. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gustafson PE. Sex differences in risk perception: theoretical and methodological perspectives. Risk Anal. 1998;18(6):805–811. doi: 10.1023/b:rian.0000005926.03250.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson BB, Slovic P. Presenting uncertainty in health risk assessment: initial studies of its effects on risk perception and trust. Risk Anal. 1995;15(4):485–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carpenter DM, Geryk LL, Chen AT, et al. Conflicting health information: a critical research need. Health Expect. 2016;19(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1111/hex.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, et al. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):847–854. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, et al. E-cigarette use among high school and middle school adolescents in Connecticut. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):810–818. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chatterjee S, Kang YS, Mishra DP. Market signals and relative preference: the moderating effects of conflicting information, decision focus, and need for cognition. J Bus Res. 2005;58(10):1362–1370. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naylor RW, Droms CM, Haws KL. Eating with a purpose: consumer response to functional food health claims in conflicting versus complementary information environments. J Public Policy Mark. 2009;28(2):221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fennis BM, Stroebe W. Psychology of Advertising. 2nd. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group; 2016. pp. 125–243. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stern PC. Learning through conflict: a realistic strategy for risk communication. Policy Sci. 1991;24(1):99–119. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasperson RE, Renn O, Slovic P, et al. The social amplification of risk: a conceptual framework. Risk Anal. 1988;8(2):177–187. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cameron TA. Updating subjective risks in the presence of conflicting information: an application to climate change. J Risk Uncertain. 2005;30(1):63–97. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wackowski OA, O'Connor RJ, Strasser AA, et al. Smokers' and e-cigarette users' perceptions of modified risk warnings for e-cigarettes. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodu B, Plurphanswat N, Hughes JR, Fagerström K. Associations of proposed relative-risk warning labels for snus with perceptions and behavioral intentions among tobacco users and nonusers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):809–816. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agostinelli G, Grube JW. Alcohol counter-advertising and the media: a review of recent research. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26(1):15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith SW, Atkin CK, Roznowski J. Are “drink responsibly” alcohol campaigns strategically ambiguous? Health Commun. 2009;20(1):91–99. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc2001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Team T. Who stands to gain from the e-cigarette phenomenon? [Accessed May 31, 2017];Forbes. 2015 Jul 23; Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2015/06/23/who-stands-to-gain-from-the-e-cigarette-phenomenon/#573eac37c8db.

- 52.Duchowski AT. Eye Tracking Methodology. 2nd. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liberman N, Trope Y. The psychology of transcending the here and now. Science. 2008;322(5905):1201–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1161958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Byrne S, Katz SJ, Mathios A, Niederdeppe J. Do the ends justify the means? A test of alternatives to the FDA proposed cigarette warning labels. Health Commun. 2014;30(7):680–693. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.895282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez D, Romer D, Audrain-McGovern J. Beliefs about the risks of smoking mediate the relationship between exposure to smoking and smoking. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(1):106–113. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802e0f0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uhrig JD, Lewis MA, Bann CM, et al. Addressing HIV knowledge, risk reduction, social support, and patient involvement using SMS: results of a proof-of-concept study. J Health Commun. 2012;17(Supp1):128–145. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.649156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lundborg P, Andersson H. Sex, risk perceptions and smoking behavior. J Health Econ. 2008;27(5):1299–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flynn J, Slovic P, Mertz CK. Sex, race, and perception of environmental health risks. Risk Anal. 1994;14(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1994.tb00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garbarino E, Strahilevitz M. Sex differences in the perceived risk of buying online and the effects of receiving a site recommendation. J Bus Res. 2004;57(7):768–775. [Google Scholar]

- 60.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No decline in overall youth tobacco use since 2011. [Accessed May 31, 2017];2016 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0414-youth-tobacco.html.

- 61.Miller CH, Burgoon M, Grandpre JR, Alvaro EM. Identifying principal risk factors for the initiation of adolescent smoking behaviors: the significance of psychological reactance. Health Commun. 2006;19(3):241–252. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1903_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zwar N, Bell J, Peters M, et al. Nicotine and nicotine replacement therapy – the facts. Pharmacist. 2006;25(12):969–973. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferguson SG, Gitchell JG, Shiffman S, et al. Providing accurate safety information may increase a smoker's willingness to use nicotine replacement therapy as part of a quit attempt. Addict Behav. 2011;36(7):713–716. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]