Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Uncertainty regarding clopidogrel effectiveness attenuation because of a drug-drug interaction with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) has led to conflicting guidelines on concomitant therapy. In particular, the effect of this interaction in patients who undergo a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), a population known to have increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, has not been systematically evaluated.

OBJECTIVE:

To synthesize the evidence of the effect of clopidogrel-PPI drug interaction on adverse cardiovascular outcomes in a PCI patient population.

METHODS:

We conducted a systematic literature review for studies reporting clinical outcomes in patients who underwent a PCI and were initiated on clopidogrel with or without a PPI. Studies were included in the analysis if they reported at least 1 of the clinical outcomes of interest (major adverse cardiovascular event [MACE], cardiovascular death, all-cause death, myocardial infarction, stroke, stent thrombosis, and bleed events). We excluded studies that were not exclusive to PCI patients or had no PCI subgroup analysis and/or did not report at least a 6-month follow-up. Statistical and clinical heterogeneity were evaluated and HRs and 95% CIs for adverse clinical events were pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects meta-analysis method.

RESULTS:

We identified 12 studies comprising 50,277 PCI patients that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Our analysis included retrospective analyses of randomized controlled trials (2), health registries (3), claims databases (2), and institutional records (5); no prospective studies of PCI patients were identified. On average, patients were in their mid-60s, male, and had an array of comorbidities, including hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking history. Concomitant therapy following PCI resulted in statistically significant increases in composite MACE (HR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.24-1.32), myocardial infarction (HR = 1.51; 95% CI = 1.40-1.62), and stroke (HR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.15-1.86). However, concomitant therapy had no statistically significant effect on stent thrombosis, mortality measured by all-cause or cardiovascular death, or major bleeding before or after the grouping of studies that reported a major or minor bleed outcome. Only 1 study reported on gastrointestinal bleed, and pooled analysis could not be conducted. Statistical testing suggested heterogeneity among studies, but subgroup analysis did not reveal a clear source.

CONCLUSIONS:

Based on the results from this meta-analysis of retrospective analyses of randomized controlled trials and observational studies, concomitant clopidogrel-PPI therapy following PCI appears to be significantly associated with adverse cardiovascular events. Further research on the effect of individual PPIs is needed.

What is already known about this subject

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), including omeprazole and esomeprazole, inhibit CYP2C19 metabolism to varying degrees and have been shown to have a pharmacokinetic effect on clopidogrel when administered concomitantly.

Meta-analyses have shown an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events with concomitant therapy, but none have focused exclusively on high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) patients.

What this study adds

This is the first meta-analysis to analyze clinical outcomes associated with the interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel in an exclusively PCI population.

Findings suggest that PCI patients on concomitant clopidogrel and PPI therapy are at higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with clopidogrel alone.

Approximately 500,000 percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures to alleviate acute coronary syndrome (ACS) ischemia are performed in the United States each year.1 The standard of care following PCI is treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy, consisting of a thienopyridine (typically clopidogrel) or ticagrelor with aspirin, to prevent reinfarction and other subsequent ischemic events.2 Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are often added to this regimen to prevent gastrointestinal hemorrhage, a serious bleeding complication associated with long-term antiplatelet therapy.3

Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that PPIs as a class attenuate the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel; however, the proposed cause of the interaction—inhibiting cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19)-facilitated metabolism of the prodrug to its active metabolite 2-oxo-clopidogrel—is stronger in some PPIs compared with others.4,5 Pharmacogenomic studies have shown that CYP2C19 variants that lead to reduced enzymatic activity lead to attenuated clopidogrel effectiveness. However, the results of studies populated by patients exhibiting a wide spectrum of ACS severity and invasive procedure use have largely been inconclusive.6 Notably, the most consistent and significant effects have been observed in patients undergoing PCI.7,8 These findings raise the question of whether concomitantly treated ACS patients, particularly those who undergo PCI, have a similarly elevated risk for poor cardiovascular outcomes.9

Clinical practice guidelines offer conflicting guidance on the significance of this interaction. In 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced a nonboxed warning to “avoid concomitant use of clopidogrel with drugs that are strong or moderate CYP2C19 inhibitors (e.g., the PPIs omeprazole and esomeprazole).”10 More recently, in 2012, clinical guidelines from the American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association stated that they do “not prohibit the use of PPI agents in appropriate clinical settings” and appeal for more randomized controlled trials (RCTs) until enough clinical evidence exists to inform a more scientifically derived recommendation.2,11-13

The preliminary results of the discontinued COGENT trial (3,761 ACS patients, 71% PCI) indicated no significant differences in clinical outcomes between clopidogrel monotherapy and concomitant omeprazole study arms.3 In the 5 ensuing years, a large number of retrospective cohort studies in various patient populations have been conducted to evaluate this drug-drug interaction and have produced largely conflicting results.14-19 Although a number of published meta-analyses have evaluated these studies,20-22 they have not focused exclusively on a PCI population.

The objective of this study was to synthesize the evidence of the effect of clopidogrel-PPI drug interaction on adverse cardiovascular outcomes in a PCI patient population. We conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of published clinical studies to evaluate whether drug-drug interactions between clopidogrel and a PPI lead to worse health outcomes in PCI patients than patients treated with clopidogrel only.

Methods

Literature Review and Eligibility Criteria

The meta-analysis followed recommendations described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.23 We conducted a systematic literature search for all relevant clinical studies and meta-analyses using PubMed, Cochrane Database, and EMBASE databases through March 2015 with the key words “proton pump inhibitor” and “clopidogrel.” We then searched the bibliographies of all database-extracted papers for additional relevant studies that the database search may have missed. Our study included any RCT or observational study that reported at least 1 of the following outcomes: major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE; a composite outcome typically composed of myocardial infarction, stroke, and/or cardiovascular death), cardiovascular (CV) death, all-cause (AC) death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, stent thrombosis (ST), thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) bleed, and gastrointestinal (GI) bleed. Studies were excluded if they were composed of non-PCI patients, if there was no PCI subgroup analysis, or if there was not at least a 6-month follow-up period to avoid studies focusing on short-term or in-hospital outcomes. Clopidogrel dose and concurrent aspirin therapy were evaluated but not used as exclusion criteria. We also collected data on study design, study size, follow-up length, and PPI used but did not exclude studies based on which individual PPI was used. Studies were assessed by 2 reviewers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Analysis

We conducted a DerSimonian and Laird method random-effects meta-analysis, which considers both within-study and between-study variation, using STATA statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).24 Similarity between hazard ratios (HRs) and odds ratios (ORs) was assumed in all outcomes of uncommon events (α < 5%), and ORs were evaluated in event rates over 5% in sensitivity analyses.25 To mitigate the risk of bias and confounding in cohort studies, we used adjusted HRs or propensity score matching HRs from these studies if available.26-28 Heterogeneity was evaluated using the Χ2 statistic and the degree assessed using the I2 measure to display overall variability of interstudy versus intrastudy heterogeneity. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis by individual exclusion of each study for each outcome to assess their effects on the pooled outcome HR. We measured significance using a P value of less than 0.05; adjustment to the P value criteria for multiple comparisons was not conducted because of the complementary nature of the hypothesis.8 Results are presented as HRs and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Studies Identified

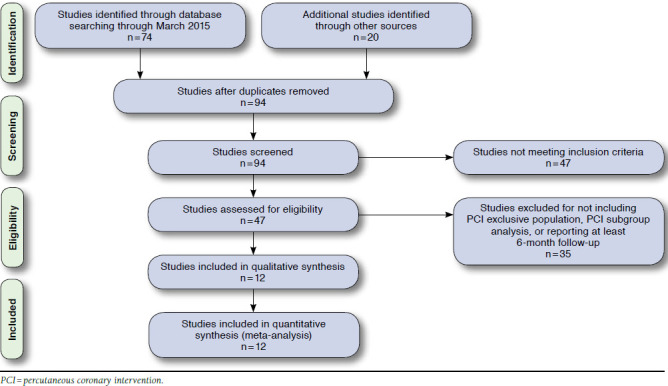

We identified 94 potentially relevant studies and screened each for inclusion, collecting data on study design, study size, follow-up length, PPI used, and efficacy and safety. Of those studies, 82 were not used because they did not use an exclusively PCI population, only provided pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic data, did not report on any of the relevant outcomes, or were not conducted for the minimum amount of time (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow Diagram of Article Selection

The final analysis included 12 retrospective analyses of RCTs (2), health registries (3), claims databases (2), and institutional records (5) and comprised 50,277 patients; no prospective studies of PCI patients were identified (Table 1). Eleven of the 12 included studies (42,295 patients, 19,695 on concomitant therapy) reported a MACE or other composite cardiovascular outcome, while 1 study reported only MI as an outcome.27-36 Included were studies conducted in a variety of countries over 3 continents (Asia, Europe, and North America), indicating broad international use of concomitant therapy in PCI patients. Overall, patient populations had similar proportions of comorbidities, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking status (Table 2). Aspirin dose and PPI drug choice varied among studies, with aspirin doses ranging from 75 mg per day to 325 mg per day and individual PPIs including omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, or lansoprazole. Compared with cardiovascular outcomes, fewer studies reported on TIMI (3 studies) and GI (1 study) bleed outcomes.26,28,31,34 Of those studies reporting a TIMI bleed outcome, 2 reported a major bleed outcome, and the other reported on a major or minor bleed outcome.28,31,34

TABLE 1.

Study Characteristics

| Study, Date | Study Design of Included Studies | Original Study Selection Criteria | Aspirin Dose | PPIs Included (in Order of Most Use) | Follow-up Time | Individual Outcomes Reported | MACE or Composite Outcome Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O’Donoghue et al. 200931 | Secondary retrospective analysis of the TRITON-TIMI 38 RCT | Patients who underwent PCI and were randomized into TRITON-TIMI 38 trial | 75-162 mg | Pantoprazole, omerprazole, esomeprazole, landoprazole, rabeprazole | 15 months | All-cause death, cardiovascular death, MI, stent thrombosis, TIMI major bleed | Cardiovascular death, MI, stroke |

| Zairis et al. 201030 | Retrospective cohort | Patients who underwent coronary stenting due to stable angina or ACS | 100-325 mg | Omeprazole | 1 year | Cardiovascular death, MI, stent thrombosis | Cardiovascular death and hospitalization for nonfatal MI |

| Kreutz et al. 201032 | Retrospective cohort | Patients at aged at least 18 years and had hospitalization claim for PCI with stent placement | NS | Esomeprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole | 1 year | Cardiovascular death, MI, stroke | Hospitalization for cerebrovascular event, ACS, cardiovascular death, coronary revascularization |

| Tentzeris et al. 201033 | Prospective registry | Patients who underwent PCI and stent implantation | 100 mg | Pantoprazole, esomeprazole, omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole | 1 year | All-cause death, cardiovascular death, stent thrombosis | All-cause death, re-ACS, stent thrombosis |

| Evanchan et al. 201042 | Retrospective cohort | Patients who underwent PCI with stent placement | NS | NS | 1 year | MI | No composite outcome |

| Rossini et al. 201134 | Retrospective cohort | Patients who underwent PCI and DES implantation | NS | Lansoprazole, pantoprazole, omeprazole | 1 year | All-cause death, stent thrombosis, TIMI major bleed | All-cause death, MI, destabilizing symptoms leading to hospitalization, nonfatal stroke |

| Harjai et al. 201128 | Retrospective cohort | Patients who underwent successful PCI of native coronary artery or bypass graft for stable or unstable coronary artery disease | NS | Omeprazole, esomeprazole (others not stated) | 6 months | All-cause death, MI, stent thrombosis, TIMI major or minor bleed | All-cause death, MI, target vessel revascularization, stent thrombosis |

| Burkard et al. 201235 | Secondary retrospective analysis of the BASKET RCT | Patients were an all-comer population undergoing PCI irrespective of clinical indication | 100 mg | Esomeprazole, pantoprazole, omeprazole, lansoprazole | 3 years | MI | Cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, target vessel revascularization |

| Aihara et al. 201226 | Retrospective cohort | Patients who underwent PCI including coronary stenting | 200 mg | Lansoprazole, omeprazole, rabeprazole | 1 year | All-cause death, MI, stroke | All-cause death or MI |

| Gupta et al. 201036 | Retrospective cohort | Patients who underwent PCI | 75 mg | Rabeprozole, omeprazole, lansoprazole | 4 years | All-cause death | Cardiovascular and all-cause death, nonfatal MI, target vessel failure |

| Banerjee et al. 201127 | Retrospective cohort | Patients who underwent PCI with coronary stent implantation | NS | Omeprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole | 1 year | All-cause death | All-cause death, nonfatal MI, repeat revascularization |

| Zou et al. 201429 | Retrospective cohort | Patients who underwent PCI with DES placement | 100 mg | Omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole | 1 year | Cardiovascular death, MI, stent thrombosis | All-cause death, MI, target vessel revascularization, target lesion revascularization CABG, stent thrombosis |

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; DES = drug-eluting stent; MACE = major adverse cardiovascular event; MI = myocardial infarction; NS = not stated; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI = proton pump inhibitor; RCT = randomized controlled trial; TIMI = thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

TABLE 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Study | Number | Age (SD) | Male n (%) | Hypertension n (%) | Hyperlipidemia n (%) | DM n (%) | Smoker n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aihara et al.26 | |||||||

| +PPI | 500 | 68 (±11.0) | 363 (72.6) | 356 (71.2) | 415 (83.0) | 204 (40.8) | 223 (44.6) |

| -PPI | 500 | 69 (±11.0) | 379 (75.8) | 345 (69.0) | 419 (83.8) | 197 (39.4) | 216 (43.2) |

| Burkard et al.35 | |||||||

| +PPI | 109 | 66.5 (±10.5) | 75 (68.8) | 79 (72.5) | 80 (73.4) | 32 (29.4) | 27 (24.8) |

| -PPI | 692 | 63.3 (±11.3) | 553 (79.9) | 450 (65.0) | 525 (75.9) | 119 (17.2) | 206 (29.8) |

| Harja et al.28 | |||||||

| +PPI | 751 | 66 (±11.0) | 463 (61.7) | 548 (73.0) | 591 (78.7) | 225 (30.0) | 160 (21.3) |

| -PPI | 1,902 | 64 (±12.0) | 1,368 (71.9) | 1,237 (65.0) | 1,335 (70.2) | 505 (26.6) | 494 (26.0) |

| Rossini et al.34 | |||||||

| +PPI | 1,158 | 64 (±11.0) | 875 (75.6) | 736 (63.6) | 762 (65.8) | 314 (27.1) | 571 (49.3) |

| -PPI | 170 | 63 (±11.0) | 138 (81.2) | 111 (65.3) | 123 (72.4) | 48 (28.2) | 84 (49.4) |

| Evanchan et al.42 | |||||||

| +PPI | 1,369 | 63.5 (NR) | NR | 837 (61.1) | 850 (62.1) | 630 (46.0) | NR |

| -PPI | 4,425 | 62.9 (NR) | NR | 2,835 (64.1) | 2,734 (61.8) | 1,601 (36.2) | NR |

| Kreutz et al.32 | |||||||

| +PPI | 6,828 | 67.5 (±10.4) | 4,232 (62.0) | 3,454 (50.6) | 4,630 (67.8) | 1,767 (25.9) | NR |

| -PPI | 9,862 | 65.2 (±10.6) | 7290 (73.9) | 4,581 (46.5) | 6,254 (63.4) | 2,238 (22.7) | NR |

| Zairis et al.30 | |||||||

| +PPI | 340 | 62.1 (±10.5) | 280 (82.4) | 173 (50.9) | 226 (66.5) | 102 (30.05) | 169 (49.7) |

| -PPI | 248 | 61.7 (±10.8) | 203 (81.9) | 115 (46.4) | 162 (65.3) | 65 (26.2) | 126 (50.8) |

| Tentzeris et al.33 | |||||||

| +PPI | 691 | 64.1 (±12.4) | 452 (65.4) | 509 (73.7) | 528 (76.4) | 129 (18.7) | 193 (27.9) |

| -PPI | 519 | 64.4 (±11.9) | 377 (72.6) | 406 (78.2) | 400 (77.1) | 135 (26.0) | 120 (23.1) |

| O’Donoghue et al.31 | |||||||

| +PPI | 2,257 | 62 (±8.0) | 1,587 (70.3) | 1,488 (65.9) | 1,274 (56.4) | 547 (24.2) | 828 (36.7) |

| -PPI | 4,538 | 60 (±8.0) | 3,390 (74.7) | 2,883 (63.5) | 2,516 (55.4) | 1,023 (22.5) | 1,755 (38.7) |

| Gupta et al.36 | |||||||

| +PPI | 72 | 61.7 (±1.2) | NR | 55 (76.4) | 48 (66.7) | 26 (36.1) | 18 (25.0) |

| -PPI | 243 | 62 (±0.7) | NR | 166 (68.3) | 146 (60.1) | 73 (30.0) | 81 (33.3) |

| Banerjee et al.27 | |||||||

| +PPI | 867 | 64.5 (±10.3) | 851 (98.2) | 801 (92.4) | 777 (89.6) | 446 (51.4) | 347 (40.0) |

| -PPI | 3,678 | 63.8 (±9.9) | 3,615 (98.3) | 3,269 (88.9) | 3,141 (85.4) | 1,630 (44.3) | 1,428 (38.8) |

| Zou et al.29 | |||||||

| +PPI | 6,188 | 66.2 (±10.2) | 4,548 (73.5) | 4,412 (71.3) | 3,725 (60.2) | 1,597 (25.8) | 1,993 (32.2) |

| -PPI | 1,465 | 65.7 (±10.6) | 1,083 (73.9) | 1,031 (70.4) | 913 (62.3) | 346 (23.6) | 454 (31.0) |

| Total/average | |||||||

| +PPI | 21,130 | 64.1 | 13,726 (69.7)a | 13,448 (63.6) | 13,906 (65.8) | 6,019 (28.5) | 4,529 (35.0)a |

| -PPI | 28,242 | 63.7 | 18,396 (78.0)a | 17,429 (61.7) | 18,668 (66.1) | 7,980 (28.3) | 4,964 (35.6)a |

a Percentages exclude populations without reported outcome.

DM = diabetes mellitus; NR = not reported; +PPI = with proton pump inhibitor; -PPI = without proton pump inhibitor; SD = standard deviation.

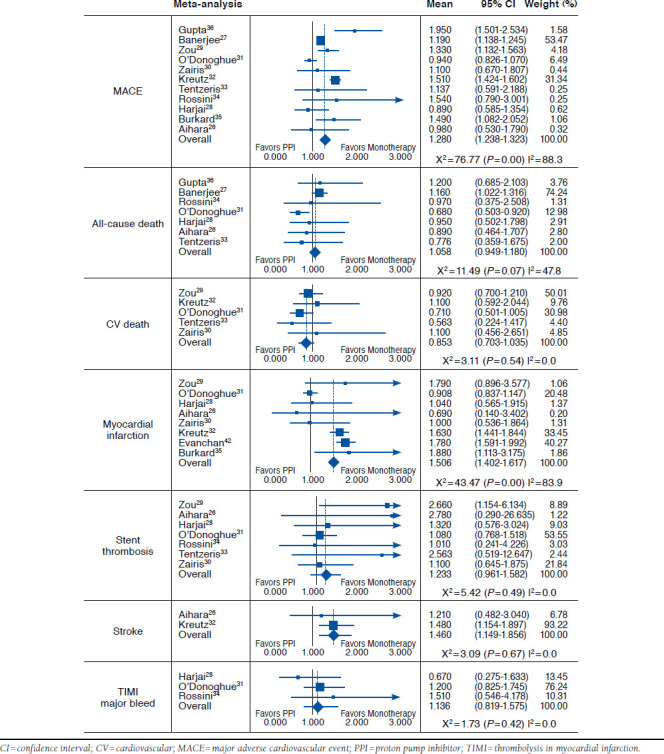

Heterogeneity Assessment

For the MACE composite outcome, heterogeneity Χ2 was 77.57 (P < 0.005) and I2 was 87.1%, displaying a high variability between studies. Comparing heterogeneity using the Χ2 and I2 statistics within each of the 5 listed outcomes under MACE generated the following results: Χ2 of 11.49 (P = 0.07) and I2 of 47.8% for AC death; Χ2 of 3.11 (P = 0.54) and I2 of 0% for CV death; Χ2 of 43.47 (P < 0.05) and I2 of 83.9% for MI; Χ2 of 5.42 (P = 0.49) and I2 of 0% for ST; and Χ2 of 3.09 (P = 0.67) and I2 of 0% for stroke. The statistically significant heterogeneity observed for MI could not be eliminated through exclusion of any single study. We did not identify evidence of heterogeneity for the safety outcome of TIMI bleed: Χ2 of 0.17 (P = 0.678) and I2 of 0%.

Cardiovascular Outcomes

Concomitant therapy showed a statistically significant increase in composite MACE outcomes compared with clopidogrel monotherapy (HR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.24-1.32; Figure 2). Of the individual components of MACE, there were statistically significant increases in risk with concomitant therapy for MI (HR = 1.51; 95% CI = 1.40-1.62) and stroke (HR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.15-1.86). The other 3 outcomes of all-cause death (HR = 1.06; 95% CI = 0.95-1.18), cardiovascular death (HR = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.70-1.04), and stent thrombosis (HR = 1.23; 95% CI = 0.96-1.58) were not statistically significant.

FIGURE 2.

Results of Pooled Analyses for MACE and Individual Clinical Outcomes

Bleeding Outcomes

The major bleed outcome had a pooled HR of 1.14 (95% CI = 0.82-1.58); however, the pooled analysis could have been affected by the grouping of major and minor bleed in the Harjai et al. (2011) study.28 When this study was removed from the analysis, the pooled HR for the remaining studies was 1.23 (95% CI = 0.87-1.75). Only the study by Aihara et al. (2012), reported a GI bleed outcome, so no pooled analysis was conducted; however, the HR reported in the Aihara et al. study was 0.30 (95% CI = 0.08-0.87).26

Sensitivity Analysis

The high level of heterogeneity in MACE could be a result of the different criteria for the composite outcome, with many studies having little overlap in the criteria to constitute a MACE compared with others (Table 1). Attempts were made to separate out studies by similar definitions of the MACE outcome, yet the little overlap in composite outcome definition made any logical grouping with a majority of the 11 studies difficult.

In a sensitivity analysis by single study exclusion for each outcome, the greatest differences were for AC death. Exclusion of Banerjee et al. (2011) changed the results in favor of concomitant therapy, to HR = 0.81 (95% CI = 0.66-1.01) although remaining not statistically significant,27 while the exclusion of O’Donoghue et al. (2009) made the results statistically significant with an HR of 1.06 (95% CI = 1.01-1.27).31 For every other outcome, the exclusion of any study did not significantly alter the results or the heterogeneity, except with MI, where exclusion of O’Donoghue et al. changed the estimate to an HR of 1.68 (95% CI = 1.55-1.82) and substantially altered the Χ2 to 7.68 (P = 0.262) and I2 to 21.9%.31

Discussion

We conducted a meta-analysis of 12 studies that included more than 50,000 PCI patients on concomitant therapy with clopidogrel and a PPI. We found that concomitant therapy is associated with a significantly increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events. Individual cardiovascular outcomes of MI and stroke significantly increased with concomitant therapy; however, concomitant therapy had no trending effect on mortality measured by all-cause or cardiovascular death.

The potential health effects of this interaction are considerable given that approximately 500,000 PCI procedures are performed annually in the United States alone.1,37,38 Our findings imply that clinical guidelines and practice should carefully consider this interaction and that additional studies evaluating the effect of individual PPIs in this patient population are warranted.

The results of this study were directionally similar to those of other concomitant therapy meta-analyses on a broader population of patients. Huang et al. (2012) included a patient population of approximately 160,000 and found a statistically significant increase in MACE (HR = 1.40; 95% CI = 1.19-1.64); however, their findings for all-cause death (HR = 1.30; 95% CI = 0.91-1.86) and cardiovascular death (HR = 1.21; 95% CI = 0.60-2.43) were nonsignificant.21 In another recent meta-analysis by Focks et al. (2013), the OR for MACE was found to be 1.63 (95% CI = 1.45-1.83); however, the OR was nominally nonsignificant in prospective studies (OR = 1.13; 95% CI 0.98-1.30).20 Both of these large studies included non-PCI patients. In contrast, this study focused specifically on PCI patients, in whom the effect of this drug-drug interaction could potentially have a larger absolute effect because of the higher baseline risk of MACE outcomes in PCI patients.7,8

Current FDA recommendations warn against the use of concomitant therapy of clopidogrel with omeprazole or esomeprazole, but not other PPIs.10 Conversely, this study evaluated PPIs as a class, and no separate analysis could be conducted for only combination therapy with omeprazole or esomeprazole because of a lack of subgroup reporting. However, a previous meta-analysis by Kwok et al. (2013) looked at this interaction by individual PPI type and found that all PPIs displayed increases in MACE when taken with clopidogrel.22 This evaluation was not exclusively PCI patients; however, the study showed that individual PPIs, such as the more potent CYP2C19 inhibitor omeprazole, might not be exclusive offenders of this drug-drug interaction. Furthermore, a recent study by Shah et al. (2015) identified an independent association between PPIs and adverse cardiovascular events using a large data-mining approach, but this was also not specific to PCI patients.39

Evaluation of rare individual events, such as all-cause or cardiovascular death, would require extremely large studies to achieve sufficient statistical power to detect differences; hence, the MACE composite outcome is typically used in clinical trials. When exploring individual outcomes, we found a significant increase in MIs (HR = 1.51; 95% CI = 1.40-1.62) and strokes (HR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.15-1.86) with concomitant therapy. Counterintuitively, outcomes of all-cause and cardiovascular death did not show a similar increased risk with combined therapy. The most likely explanation for this finding is that the studies were underpowered to assess mortality.

Limitations

A significant limitation of this study was that the composite MACE outcomes were not defined uniformly among the pooled studies. While most studies included some combination of MI, stroke, and/or cardiovascular death, the exclusion of any of these or the inclusion of additional outcomes such as stent thrombosis may have affected the results. While an attempt was made to stratify based on MACE definition, the lack of overlap between studies made it difficult to pool studies in large enough groups to perform separate analyses. Other limitations included (a) not studying PPIs by individual drug, (b) the lack of standardization for aspirin dosage among studies, (c) no uniform time to endpoint in each study, (d) a lack of studies reporting on gastrointestinal events, and (e) possible confounding by indication (e.g., patients taking PPIs are more likely to be older and sicker and thus more likely to experience a MACE outcome) is a concern in all of the observational studies included in this analysis. The overall consistent increase in MIs and strokes exhibited in patients on concomitant therapy after a PCI suggest that our findings are robust to some confounding factors.

A further limitation is the possibility of inconsistent quality between studies. Drepper et al. (2012) raised this issue in a systematic review of PCI and non-PCI patients.40 Findings from 3 previous meta-analyses suggested high-quality (well-performed RCTs) and moderate-quality (post hoc analysis of RCTs and propensity matched studies) studies found a decreased MACE interaction, or lack of a statistically significant interaction, when compared with low-quality studies (observational studies without propensity matching or adjustment).40 Thus, unmeasured confounders might be a cause of the results in lower quality studies.41 In our study, where no high-quality RCTs met inclusion criteria, separate analysis by study quality was not performed; however, all of the studies included in our analysis had either internal adjustments or used propensity matching. Yet, in the O’Donoghue et al. study, a post hoc analysis of an RCT and likely the study of highest quality in our analysis, the MACE interaction HR showed no risk difference for concomitant therapy.31

Conclusions

This meta-analysis of retrospective analyses of RCTs and observational studies evaluating PCI-specific patients receiving concomitant PPI-clopidogrel versus clopidogrel monotherapy suggests that concomitant therapy may be associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. Further research on the effect of individual PPIs is needed.

References

- 1.Marso SP, Teirstein PS, Kereiakes DJ, Moses J, Lasala J, Grantham JA.. Percutaneous coronary intervention use in the United States: defining measures of appropriateness. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(2):229-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Spencer FA, Baglin TP, Weitz JI.. Antiplatelet drugs: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e89S-119S. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3278069/. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1909-17. Available at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1007964. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbel Y, Birati EY, Finkelstein A, et al. Platelet inhibitory effect of clopidogrel in patients treated with omeprazole, pantoprazole, and famotidine: a prospective, randomized, crossover study. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(6):342-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (omeprazole CLopidogrel aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(3):256-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes MV, Perel P, Shah T, Hingorani AD, Casas JP.. CYP2C19 genotype, clopidogrel metabolism, platelet function, and cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306(24):2704-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaglia MA Jr, Torguson R, Hanna N, et al. Relation of proton pump inhibitor use after percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents to outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(6):833-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mega JL, Simon T, Collet JP, et al. Reduced-function CYP2C19 genotype and risk of adverse clinical outcomes among patients treated with clopidogrel predominantly for PCI: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1821-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazui M, Nishiya Y, Ishizuka T, et al. Identification of the human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the two oxidative steps in the bioactivation of clopidogrel to its pharmacologically active metabolite. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(1):92-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Interaction between esomeprazole/omeprazole and clopidogrel label change. Updated December 11, 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm327922.htm. Accessed June 26, 2016.

- 11.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham NS, Hlatky MA, Antman EM, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 expert consensus document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(12):2533-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, O’Gara PT, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt M, Johansen MB, Robertson DJ, et al. Concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors is not associated with major adverse cardiovascular events following coronary stent implantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(1):165-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray WA, Murray KT, Griffin MR, et al. Outcomes with concurrent use of clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitors: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(6):337-45. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3176584/. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockl KM, Le L, Zakharyan A, et al. Risk of rehospitalization for patients using clopidogrel with a proton pump inhibitor. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):704-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman SG, Clare R, Pieper KS, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitor use on cardiovascular outcomes with clopidogrel and ticagrelor: insights from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes Trial. Circulation. 2012;125(8):978-86. Available at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/125/8/978.long. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Johansson S, Cea Soriano L.. Use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors after a serious acute coronary event: risk of coronary events and peptic ulcer bleeding. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(5):1014-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009;301(9):937-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Focks JJ, Brouwer MA, van Oijen MG, Lanas A, Bhatt DL, Verheugt FW.. Concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors: impact on platelet function and clinical outcome—a systematic review. Heart. 2013;99(8):520-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang B, Huang Y, Li Y, et al. Adverse cardiovascular effects of concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(3):212-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwok CS, Jeevanantham V, Dawn B, Loke YK.. No consistent evidence of differential cardiovascular risk amongst proton-pump inhibitors when used with clopidogrel: meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(3):965-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Kacker R.. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):105-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Symons MJ, Moore DT.. Hazard rate ratio and prospective epidemiological studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):893-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aihara H, Sato A, Takeyasu N, et al. Effect of individual proton pump inhibitors on cardiovascular events in patients treated with clopidogrel following coronary stenting: results from the Ibaraki Cardiac Assessment Study Registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80(4):556-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banerjee S, Weideman RA, Weideman MW, et al. Effect of concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(6):871-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harjai KJ, Shenoy C, Orshaw P, Usmani S, Boura J, Mehta RH.. Clinical outcomes in patients with the concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors after percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Guthrie Health Off-Label Stent (GHOST) Investigators. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(2):162-70. Available at: http://circinterventions.ahajournals.org/content/4/2/162.long. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou JJ, Chen SL, Tan J, et al. Increased risk for developing major adverse cardiovascular events in stented chinese patients treated with dual antiplatelet therapy after concomitant use of the proton pump inhibitor. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84985. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3885647/. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zairis MN, Tsiaousis GZ, Patsourakos NG, et al. The impact of treatment with omeprazole on the effectiveness of clopidogrel drug therapy during the first year after successful coronary stenting. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26(2):e54-e57. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2851393/. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;374(9694):989-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreutz RP, Stanek EJ, Aubert R, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on the effectiveness of clopidogrel after coronary stent placement: the clopidogrel medco outcomes study. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(8):787-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tentzeris I, Jarai R, Farhan S, et al. Impact of concomitant treatment with proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel on clinical outcome in patients after coronary stent implantation. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(6):1211-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rossini R, Capodanno D, Musumeci G, et al. Safety of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors in patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation. Coron Artery Dis. 2011;22(3):199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burkard T, Kaiser CA, Brunner-La Rocca H, et al. Combined clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitor therapy is associated with higher cardiovascular event rates after percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the BASKET trial. J Intern Med. 2012;271(3):257-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta E, Bansal D, Sotos J, Olden K.. Risk of adverse clinical outcomes with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following percutaneous coronary intervention. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(7):1964-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidelbaugh JJ, Kim AH, Chang R, Walker PC.. Overutilization of proton-pump inhibitors: what the clinician needs to know. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5(4):219-32. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3388523/. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cutlip D, Nicolau JC.. Antiplatelet therapy after coronary artery stenting. UpToDate. Updated May 11, 2016. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/antiplatelet-therapy-after-coronary-artery-stenting. Accessed June 26, 2016.

- 39.Shah NH, LePendu P, Bauer-Mehren A, et al. Proton pump inhibitor usage and the risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0124653. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4462578/. Accessed June 26, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drepper MD, Spahr L, Frossard JL.. Clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors—where do we stand in 2012? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(18):2161-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwok CS, Loke YK.. Meta-analysis: the effects of proton pump inhibitors on cardiovascular events and mortality in patients receiving clopidogrel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(8):810-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evanchan J, Donnally MR, Binkley P, Mazzaferri E.. Recurrence of acute myocardial infarction in patients discharged on clopidogrel and a proton pump inhibitor after stent placement for acute myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):168-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]