Abstract

Background:

We identified predictors of receiving treatment (brief therapy [BT] and/or extended-release injectable naltrexone [XR-NTX]) for the treatment of alcohol use disorders (AUDs) in primary care. We also examined the relationship between receiving BT and XR-NTX.

Methods:

Secondary data analysis of SUMMIT, a randomized controlled trial of collaborative care. Participants were 290 individuals with AUDs who reported no past 30-day opioid use and who were receiving primary care at a multi-site Federally Qualified Health Center. Bivariate and multivariate analyses examined predictors of BT and/or XR-NTX.

Results:

Thirty-two percent (N=93) received either BT or XR-NTX, 28% (N=82) received BT and 13% (N=37) received XR-NTX; 9% (N=26) received both BT and XR-NTX. Older age, white race, talking with a professional about alcohol use and having more negative consequences all predicted receipt of evidence-based treatment; being homeless was a negative predictor. The predictors of receiving BT included not being homeless and previously talking with a professional; the predictors of receiving XR-NTX included older age, white race and experiencing more negative consequences. In 80% of those who received both BT and XR-NTX, receipt of BT preceded XR-NTX.

Conclusions:

Patient factors were important predictors of receiving primary-care based AUD treatment and differed by type of treatment received. Receiving BT was associated with subsequent use of XR-NTX and may be associated with a longer duration of XR-NTX treatment. Providers should consider these findings when considering ways to increase primary-care based AUD treatment.

Keywords: Alcohol use disorder, Treatment utilization, Primary care, Brief treatment, Extended-Release injectable naltrexone

1. Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are among the behavioral health disorders with the lowest rates of treatment utilization (Cohen et al., 2007). In the United States, 15.8 million individuals had a current need for treatment, yet in 2015 only 1.9 million (12%) received treatment for an alcohol problem (SAMHSA, 2016). The consequences of unmet need are great, and include increased morbidity and mortality, avoidable healthcare costs, and long-term harmful effects on families and communities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; Kanny et al., 2015; Roerecke and Rehm, 2013; Sacks et al., 2015; Yoon and Yi, 2012). Increasing access to treatment could reduce individual suffering, improve healthcare outcomes, and decrease health care costs (Harwood et al., 2009; Substance Abuse Policy Research Program, undated).

Reasons for low AUD treatment utilization are understudied. Population-based studies have generally found that older age, male gender, lower education, lower income, higher substance use severity, and comorbid psychiatric and/or drug use disorders are associated with receiving treatment and that the most common type of treatment accessed was Alcoholics Anonymous (Cohen et al., 2007). Having previously accessed treatment was one of the most important correlates of current treatment entry. Studies examining access to specialty care have found similar results, with the client’s age, gender, marital status, income, education, the perceived need for treatment, and prior use of services being important factors associated with specialty treatment utilization (Ilgen et al., 2011; Weisner et al., 2002).

Few studies have examined predictors of primary-care based treatment. A single study in the United States compared factors associated with initiating specialty care vs. general medical care and found that being married, college student status, having more medical conditions, and having co-morbid substance dependence all increased the probability of initiating care (Dawson et al., 2012). Cross-sectional studies done in Europe found that co-morbid depression and anxiety, alcohol-related medical complications, and the daily amount of alcohol used (Rehm et al., 2015a,b) all increased the likelihood patients would be identified and use primary-care based treatment. Neither of these studies, however, examined specific treatment types. This is important because the two broad types of evidence-based treatment, psychotherapy and medication-assisted treatment (MAT), depend on different workforces and require different organizational resources. A single study examining correlates of specialty care for AUDs in the Department of Veterans Affairs, identified co-morbid mental health and drug use disorders, Hispanic ethnicity and black race as being significantly associated with receipt of treatment, but did not examine the type of treatment accessed (Glass et al., 2010). Given the key role patients play in deciding to initiate care, and the emerging importance of integrated models of treatment, it is important to understand what factors are associated with utilization of primary-care based AUD treatment, and whether patient characteristics influence treatment selection.

The Andersen model provides a framework to understand utilization and treatment selection (Andersen, 2008; Andersen et al., 2013) and posits three categories of factors explain use. Predisposing factors include patient characteristics such as gender, race, and age; variations in utilization across predisposing factors may suggest disparities in access. Enabling factors that serve to make utilization either easier or more difficult and include characteristics such as insurance status and housing status. Need includes both perceived and actual need for health care and includes illness severity and medical and drug use co-morbidity.

Primary care is emerging as an essential and underutilized setting in which to identify and treat AUDs (National Academy for State Health Policy, 2017). Although specialty care is important for individuals with severe disorders, limited availability and stigma mean it is unlikely that specialty care alone will be able to meet all unmet need. Among individuals with substance use disorders who were not currently in treatment, more report being willing to enter primary-care based treatment (Barry et al., 2016) than specialty care. While it is unknown why primary care-based treatment may be more appealing, primary care offers the flexibility for patients to choose treatments along with a continuum and according to preference. This may be especially important in primary care, where patients are often being seen for issues the patient does not see as related to their alcohol use, and where they may not identify as having a disorder. Understanding predictors of primary-care based AUD treatment utilization may help providers and policymakers consider ways to increase utilization for individuals who may want treatment but who are unable or unwilling to access specialty care.

The current study is a secondary analysis of data from the Substance Use Motivation and Medication Integrated Treatment (SUMMIT) randomized controlled trial of the impact of collaborative care (CC) on treatment for alcohol and/or opioid use disorders (OAUD) (Ober et al., 2015; Watkins et al., 2017). The two treatments supported were a six-session brief psychotherapy treatment (BT) (Osilla et al., 2016), and/or medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with either extended-release injectable naltrexone (XR-NTX) for AUDs or Buprenorphine/naloxone for opioid use disorders (Heinzerling et al., 2016). We report here on the subgroup of participants with primary AUDs and examine patient predictors of utilization. We also examine the temporal relationship between receiving BT and XR-NTX, and, because we hypothesized that engaging in BT would promote adherence to XR-NTX, examine whether receiving BT was associated with more use of XR-NTX.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study overview

This study used data collected as part of the SUMMIT trial (Watkins et al., 2017). The CC intervention included population-based patient monitoring and tracking by a care coordinator and integration of addiction expertise through a psychologist affiliated with the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. The study was conducted in partnership at two clinics within a multi-site Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), located in Los Angeles, California that at the time of this study provided on-site behavioral health care for depression and anxiety disorders but not substance use disorders. Of 114,512 patients seen in 2016, 58% were of Hispanic origin, and 11% were African-American; the 28 full-time medical providers include internists, family practitioners, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. At the time of the study, there were 7 behavioral health providers.

All patients attending primary care were screened by a medical assistant using a 3-question screener based on the NIDA quick screen (National Institute on Drug Abuse, undated). Consenting patients with risky use were referred for additional assessment. Inclusion criteria were (1) age 18 years or older; (2) probable OAUD diagnosis, based on the NIDA-modified ASSIST; (3) English or Spanish-speaking; (4) willing to switch behavioral health therapists if already receiving therapy at the clinic. Exclusion criteria were (1) marked functional impairment from bipolar disorder or schizophrenia (Arbuckle et al., 2009; Luciano et al., 2010); and (2) currently receiving OAUD treatment.

2.2. Assessments

The baseline assessment included demographics; homeless status; past 30-day use of alcohol and opioids using the Timeline Follow-back (TLFB) (Sobell and Sobell, 1992); DSM IV diagnoses of alcohol, heroin, and prescription opioid abuse or dependence using the Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Version 3.0, sections 11 and 12 (Forman et al., 2004; Haro et al., 2006); consequences of substance use using the Short Inventory Of Problems Alcohol and Drugs (SIP-AD) (Alterman et al., 2009; Blanchard et al., 2003); depression symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (Gelaye et al., 2014; Kroenke et al., 2001); emergency department or hospital stay related to substance use in the past 90 days; and previous use of substance use treatment, including whether or not they had spoken with a professional about their use. Patients were included in the current study if they had a diagnosis of an AUD based on the CIDI and did not report opioid use in the 30-days prior to the assessment; some had a co-morbid opioid use disorder that was in remission. We excluded individuals who endorsed opioid use in the previous 30-days (N = 96) to examine the behavior of individuals for whom alcohol was the focus of treatment. We combined individuals from both arms of the parent study to maximize sample size, because we had no reason to believe that the two arms would be different, and because, despite the CC intervention, in both arms most did not access care (39% vs. 17%).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Dependent variables

We examined three binary outcome variables: initiation of any evidence-based treatment (either BT or XR-NTX), initiation of any BT, and initiation of any XR-NTX. Sample size precluded examining predictors of receiving both BT and XR-NTX. BT visit data were obtained from electronic medical record files, and XR-NTX data were obtained from a pharmacy dispensing log. The comparison groups are everyone who did not receive any evidence-based treatment, everyone who did not receive BT, and everyone who did not receive XR-NTX.

2.3.2. Predictor variables

We used the Andersen model of health care utilization (Andersen, 2008; Andersen et al., 2013) to organize and select predictor variables. Predisposing characteristics included age, gender identity, race (White, Black other/multiple races), Hispanic ethnicity, married or living with a partner, and having at least a high school education. Enabling or inhibiting resources included being homeless; currently working full or part-time for pay; having talked previously with a professional about alcohol use, and depression symptoms. Professional help was defined as talking with a medical doctor, psychologist, counselor, spiritual advisor, herbalist, acupuncturists, or other healing professional. Need or severity factors included having a co-occurring opioid use disorder in remission in addition to AUD, having had an emergency department visit or hospital stay in the past 90 days, and endorsing more negative consequences related to substance use. We also included in all models a site fixed effect and whether the patient was assigned to CC in the original study. For models predicting use of BT, we included whether the person also received XR-NTX and for models predicting use of XR-NTX we included whether the person also received BT.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses to test the baseline differences between participants who did and did not receive any evidence-based treatment (BT or XR-NTX), any BT, or any XR-NTX using a chi-squared test for categorical variables and a t-test for continuous variables. We assessed the collinearity of predictor variables and included in the multivariate analyses predictors that were significantly different between groups at a relaxed alpha level of less than 0.10. We conducted multivariate logistic regression to test which characteristics were predictive of the three outcome variables, controlling for clinic enrollment site, clinical trial assignment group, and receipt of the other evidence-based treatment, (i.e., receipt of BT when predicting receipt of XR-NTX and vice versa). To confirm our decision to combine data from both arms of the study, we repeated the analyses, stratifying by treatment assignment.

We examined the temporal relationship between receipt of BT and XR-NTX, and, because we hypothesized that engaging in BT would promote adherence to XR-NTX, we created a histogram to display the distribution of XR-NTX doses received by whether the individual also received BT. We examined the median and the modal number of doses of XR-NTX received by whether the person also received BT.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population. Nearly half were homeless, a quarter had a co-occurring opioid use disorder in remission, and 35.5% had an ER visit or overnight hospital stay in the previous 90 days. Thirty-two percent (N = 93) received either BT or XR-NTX, 28% (N = 82) received BT-only, and 13% (N = 37) received XR-NTX-only; 9% (N = 26) received both BT and XR-NTX. In all bivariate analyses, having previously talked with a professional and reporting more negative consequences for substance use were associated with utilization; being homeless was negatively associated with utilization. In the bivariate analyses examining the likelihood of receipt of any evidence-based treatment, we additionally observed significant associations with age, female gender, and having a high school education or more, an income of greater than $20,000 per year, and a higher PHQ-8 depression score. Individuals receiving BT were also significantly more likely to be female, to endorse more depressive symptoms, and to receive XR-NTX. Individuals receiving XR-NTX were more likely to be older, female, white, have a high school education or more, and to receive BT. Among the 26 individuals who received both BT and XR-NTX, 21 (80%) started with BT before receiving XR-NTX.

Table 1.

Prevalence of predisposing, enabling and need factors of primary care patients with alcohol use disorders and stratified by receipt of any evidence-based treatment and treatment type.

| All |

Received any evidence-based practice |

No evidence-based practice |

P-value | Received brief therapy |

No brief therapy |

P-value | Received XR-NTX |

No XR-NTX |

P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | |||

| Predisposing | |||||||||||||||||

| Age | 43.0 | 11.8 | 45.0 | 11.3 | 42.0 | 12.0 | 0.046 | 44.8 | 11.21 | 42.3 | 12.02 | 0.105 | 48.0 | 11.59 | 42.2 | 11.71 | 0.005 |

| Male | 219 | 75.5 | 62 | 66.7 | 157 | 79.7 | 0.016 | 54 | 65.9 | 165 | 79.3 | 0.016 | 22 | 59.5 | 197 | 77.9 | 0.015 |

| White | 118 | 40.7 | 45 | 48.4 | 73 | 37.1 | 0.067 | 40 | 48.8 | 78 | 37.5 | 0.078 | 23 | 62.2 | 95 | 37.5 | 0.004 |

| Hispanic | 98 | 33.8 | 31 | 33.3 | 67 | 34.0 | 0.909 | 28 | 34.1 | 70 | 33.7 | 0.936 | 10 | 27.0 | 88 | 34.8 | 0.352 |

| Married/living w partner | 55 | 19.0 | 22 | 23.7 | 33 | 16.8 | 0.162 | 18 | 22.0 | 37 | 17.8 | 0.415 | 10 | 27.0 | 45 | 17.8 | 0.181 |

| High school education or more | 123 | 42.4 | 48 | 51.6 | 75 | 38.1 | 0.029 | 42 | 51.2 | 81 | 38.9 | 0.057 | 23 | 62.2 | 100 | 39.5 | 0.009 |

| Enabling/inhibiting resources | |||||||||||||||||

| Income over $20,000 per year | 70 | 24.3 | 30 | 32.6 | 40 | 20.4 | 0.024 | 25 | 30.9 | 45 | 21.7 | 0.105 | 13 | 35.1 | 57 | 22.7 | 0.100 |

| Homeless | 136 | 46.9 | 25 | 26.9 | 111 | 56.3 | <0.001 | 24 | 29.3 | 112 | 53.8 | <0.001 | 10 | 27.0 | 126 | 49.8 | 0.010 |

| Working full or part-time | 83 | 28.6 | 32 | 34.4 | 51 | 25.9 | 0.134 | 27 | 32.9 | 56 | 26.9 | 0.308 | 14 | 37.8 | 69 | 27.3 | 0.184 |

| Ever talked to professional about alcohol use | 151 | 52.2 | 61 | 65.6 | 90 | 45.9 | 0.002 | 54 | 65.9 | 97 | 46.9 | 0.004 | 25 | 67.6 | 126 | 50.0 | 0.046 |

| Received treatment for alcohol in past 12 months | 32 | 11.1 | 15 | 16.1 | 17 | 8.7 | 0.059 | 12 | 14.6 | 20 | 9.7 | 0.225 | 6 | 16.2 | 26 | 10.3 | 0.286 |

| PHQ8 scale for depression | 10.9 | 6.5 | 12.1 | 6.9 | 10.3 | 6.2 | 0.028 | 12.2 | 6.83 | 10.4 | 6.26 | 0.032 | 11.4 | 7.31 | 10.8 | 6.34 | 0.623 |

| Need | |||||||||||||||||

| Co-occurring diagnosis of opioid use disorder in remission | 72 | 24.8 | 25 | 26.9 | 47 | 23.9 | 0.578 | 22 | 26.8 | 50 | 24.0 | 0.620 | 12 | 32.4 | 60 | 23.7 | 0.252 |

| ER visit or overnight hospital stay in past 90 days | 103 | 35.5 | 33 | 35.5 | 70 | 35.5 | 0.993 | 29 | 35.4 | 74 | 35.6 | 0.973 | 13 | 35.1 | 90 | 35.6 | 0.959 |

| Negative consequences from substance use | 8.5 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 7.7 | 5.0 | <0.001 | 9.7 | 4.79 | 8.0 | 5.04 | 0.006 | 10.6 | 4.17 | 8.2 | 5.08 | 0.006 |

| Received XR-NTX | 37 | 12.8 | - | - | - | - | - | 26 | 31.7 | 11 | 5.3 | <0.001 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Received brief therapy | 82 | 28.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 26 | 70.3 | 56 | 22.1 | <0.001 |

Note: XR-NTX = Injectable Extended-Release Naltrexone; SD = standard deviation; PHQ8 = eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale; ER = emergency room.

Tables 2–4 show the results of the multivariate logistic regression for the three outcome variables: either evidence-based treatment, BT, and XR-NTX. In the multivariate analysis predicting either evidence-based treatment, older age, being of white race, talking with a professional about alcohol use, and having more negative consequences were associated with an increased likelihood of treatment utilization; being homeless was associated with a decreased likelihood of treatment utilization. In the multivariate analysis predicting BT utilization, talking with a professional was positively associated with utilization; being homeless was negatively associated with utilization. In the multivariate analysis predicting XR-NTX utilization, older age, white race, and higher negative consequences predicted utilization. Results from the stratified analyses were similar in magnitude and direction, except that having a high school education or more became a significant predictor of BT in the comparison arm.

Table 2.

Predictors of receipt of evidence-based treatment among primary care patients with alcohol use disorder* (N = 290).

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Odds ratio | Low | High | P-value |

| Predisposing | ||||

| Age | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 0.009 |

| Male | 0.83 | 0.37 | 1.89 | 0.661 |

| White | 2.44 | 1.24 | 4.78 | 0.010 |

| Hispanic | ||||

| Married/living w partner | ||||

| High school education or more | 1.19 | 0.61 | 2.29 | 0.614 |

| Enabling/inhibiting resources | ||||

| Income over $20,000 per year | 1.56 | 0.74 | 3.30 | 0.245 |

| Homeless | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.39 | < 0.001 |

| Working full or part-time | ||||

| Ever talked to professional about alcohol use | 2.66 | 1.28 | 5.49 | 0.008 |

| Received treatment for alcohol in past 12 months | 0.99 | 0.32 | 3.07 | 0.986 |

| PHQ8 scale for depression | 1.01 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 0.756 |

| Need | ||||

| Co-occurring diagnosis of opioid use disorder | ||||

| ER visit or overnight hospital stay in past 90 days | ||||

| Negative consequences from substance use | 1.17 | 1.08 | 1.27 | < 0.001 |

Note: PHQ8 = eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale; ER = emergency room; CI = confidence interval.

All models included site and clinical trial enrollment group.

Table 4.

Predictors of receipt of XR-NTX among primary care patients with alcohol use disorder* (N = 290).

| 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Odds ratio | Low | High | P-value |

| Predisposing | ||||

| Age | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 0.0071 |

| Male | 0.94 | 0.35 | 2.50 | 0.9032 |

| White | 3.27 | 1.36 | 7.86 | 0.0083 |

| Hispanic | ||||

| Married/living w partner | ||||

| High school education or more | 1.70 | 0.72 | 4.01 | 0.2258 |

| Enabling/inhibiting resources | ||||

| Income over $20,000 per year | ||||

| Homeless | 0.39 | 0.14 | 1.06 | 0.0657 |

| Working full or part-time | ||||

| Ever talked to professional about alcohol use | 1.10 | 0.44 | 2.71 | 0.8421 |

| Received treatment for alcohol in past 12 months | ||||

| PHQ8 scale for depression | ||||

| Need | ||||

| Co-occurring diagnosis of opioid use disorder | ||||

| ER visit or overnight hospital stay in past 90 days | ||||

| Negative consequences from substance use | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.26 | 0.0062 |

| Received brief therapy | 3.83 | 1.50 | 9.75 | 0.0049 |

Note: XR-NTX = Injectable Extended-Release Naltrexone; PHQ8 = eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale; ER = emergency room; Cl = confidence interval.

A11 models included site and clinical trial enrollment group.

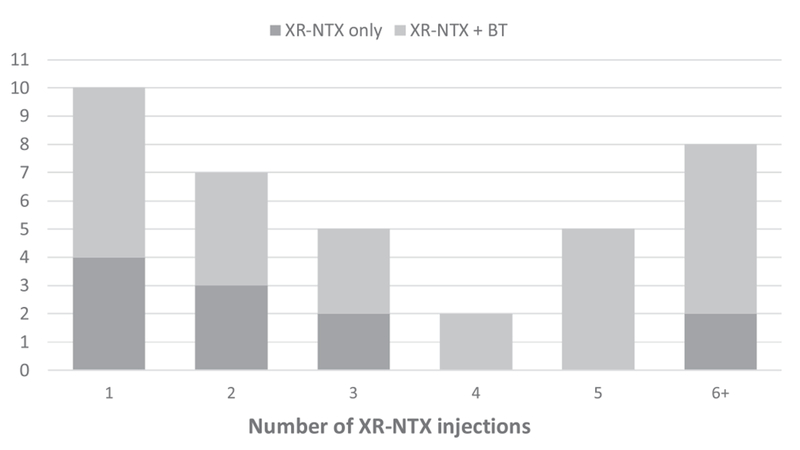

Fig. 1 shows the number of XR-NTX injections the patient received by whether the patient also received BT. For patients who received XR-NTX alone, the median number of injections was 2, and the mode was 1. For patients receiving both XR-NTX and BT, the median number of injections was 3.5, and the mode was 6 or more.

Fig. 1.

Histogram: Number of extended-release injectable naltrexone injections, by OAUD treatment group.

Note: OAUD = opioid and alcohol use disorders; XR-NTX = Extended-Release Injectable Naltrexone; XR-NTX + BT = Extended-Release Injectable Naltrexone and Brief Therapy.

4. Discussion

Among patients with AUDs receiving primary care, in multivariate analyses the predictors of receiving any AUD treatment included older age, being of white race, homeless status, talking with a professional about one’s alcohol use, and reporting more negative consequences. When specific types of treatment were examined, being homeless was a predictor of the decreased likelihood of receiving BT and talking with a professional was a predictor of increased likelihood of receiving BT; predictors of receiving XR-NTX included older age, being of white race, and experiencing more negative consequences. An examination of the temporal relationship between receipt of BT and XR-NTX indicated that in 80% of the cases, BT preceded receipt of XR-NTX and that receiving BT appeared to be associated with more use of XR-NTX.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify factors associated with receipt of BT and/or XR-NTX for the treatment of AUD in primary care and to examine the temporal relationship between receipt of BT and XR-NTX. Primary care providers are a key component of efforts to increase access to AUD treatment. Although screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is widely recommended, for those individuals with an AUD, SBIRT has not been effective in linking patients with specialty treatment (Glass et al., 2015). Thus, recent efforts to increase access have focused on increasing the delivery of primary-care based AUD treatment (Bobb et al., 2017; Rehm et al., 2016; Spithoff and Kahan, 2015). However, because individuals identified through population-based screening may be different in important ways from those entering specialty care, characterizing who receives primary care-based treatment may help providers and policymakers design more effective interventions. Identifying which patients select which treatments are important area for future research.

Consistent with previous research, the need was an important and appropriate determinant of utilization. When examining specific types of treatment, having more negative consequences predicted receipt of XR-NTX. Previously having spoken with a professional was also a significant predictor of any treatment, and utilization of BT, suggesting that conversations with health care providers, even if they do not immediately result in treatment utilization, may help individuals recognize the negative impact of excessive alcohol use and motivate them for treatment. This finding is consistent with previous research that has found that intervention by medical professionals was an important precursor of specialty treatment access (Kaner et al., 2007; Weisner et al., 2002), and with studies that have found that illness severity, as measured by a diagnosis of alcohol dependence as compared to alcohol abuse, is associated with pharmacotherapy use (Harris et al., 2010).

Understanding whether treatment utilization varies by patient characteristics unrelated to need can also shed light on the equity of access. In this regard, it is concerning that non-white individuals were less likely to receive any evidence-based treatment, even after controlling for indicators of need. When comparing predictors of any BT and any XR-NTX, this result appears to be primarily driven by individuals of white race being more likely to receive XR-NTX. It is not known whether the stronger relationship between receipt of XR-NTX and white race is driven by patient preference or by factors related to the health system; future research should investigate this further. While our findings are consistent with previous research in veterans, there is contradictory evidence on the role of race and ethnicity in treatment utilization adjusted for need (Vaeth et al., 2017; Verissimo and Grella, 2017; Williams et al., 2017).

People who are homeless face many barriers accessing and receiving both medical care and AUD treatment (Baggett et al., 2010; Holtyn et al., 2017; Koegel et al., 1999; Kushel et al., 2001; Orwin et al., 1999; Wenzel et al., 2001). AUDs are common in homeless individuals, and chronically homeless individuals with AUDs have high rates of medical and psychiatric co-morbidity (Aldridge et al., 2017; Dunne et al., 2015; Fazel et al., 2014; Montgomery et al., 2016). In our study, homelessness was a large and significant predictor of not receiving any treatment, and specifically of not receiving BT. The observation that being homeless was not negatively associated with receipt of XR-NTX is consistent with a recent report that, in the context of receiving care at a community-based organization that endorsed a harm-reduction approach, homeless individuals will accept XR-NTX (Collins et al., 2015). Understanding homeless individuals’ preferences for AUD treatment may shed further light on this finding and should be examined in subsequent research, given the strong association between homelessness and poor outcomes. Further research should confirm whether XR-NTX treatment for AUD is seen by individuals who are homeless as an acceptable and preferable treatment option compared to psychotherapy. More generally, identifying predictors of who enters treatment and receives which treatments could contribute to interventions to increase treatment rates and reduce the harms associated with untreated AUDs.

Having a co-occurring opioid use disorder or depression symptoms did not predict treatment in multivariate analyses, although it was significant in the bivariate analyses (Chartier et al., 2016; Cohen et al., 2007). In epidemiological studies, having a co-occurring drug and alcohol use disorder, or psychiatric disorder is correlated with increased access (Han et al., 2017; Park-Lee et al., 2012). It is possible that in these analyses because we excluded individuals with past 30-day opioid use, the severity level of the opioid use disorder was not high enough to result in increased utilization. It is also possible that either patients or providers may not have wanted to use XR-NTX in patients with co-morbid AUD and opioid use, and we excluded patients currently in OUD treatment. Because we measured depressive symptoms and excluded individuals who were currently receiving behavioral health care and not willing to switch therapists, we may have obscured the relationship between a depressive disorder and treatment utilization. Future studies should investigate this further.

It is notable that 80% of individuals who received both BT and XR-NTX started with BT. This suggests that primary care patients may prefer to initiate treatment with psychotherapy rather than pharmacotherapy and suggests it may be important for providers to offer both types of treatment. It is also noteworthy that both the median and the modal number of XR-NTX injections was higher in patients who also received BT and suggests that receipt of BT may be associated with longer-term use of XR-NTX. Substantial research has found that better adherence to pharmacotherapy is associated with lower relapse rates (Department of Veteran Affairs, 2015; Jonas et al., 2014).

There are several limitations to this study. The study took place at a single, multi-site FQHC, with a large homeless population and integrated behavioral health, limiting generalizability. The original study was a randomized controlled trial, and although there were few exclusion criteria and more than 90% of identified and eligible patients enrolled in the study, this may impact generalizability. The FQHC was participating in a study to increase access to AUD treatment, and, while we included the CC intervention as a covariate, it is possible that subjects in the CC and comparison arms had different patient-level predictors, although this was not supported when we conducted stratified analyses. We examined treatment initiation and did not look at retention; future studies should examine predictors of treatment retention. We only examined one type of pharmacotherapy, and our findings may not apply to other medications for AUDs. While we included in our models co-occurring opioid use disorders, we did not measure and include other drug use disorders. Our study does not include any measures of motivation or readiness to change, both of which are associated with treatment entry (DiClemente et al., 2009; Penberthy et al., 2011). While we observed associations between predisposing, enabling, and need factors with treatment utilization, we do not know the cause of the associations or whether they are driven by patient or provider factors. We did not examine whether outcomes differed by treatment type, because 26 individuals received both treatments, making the sample sizes too small for analysis. This is an important area for future research. Because of the small sample size, caution should be taken when interpreting the relationship between BT and the use of XR-NTX.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this is the first study to examine predictors of any evidence-based treatment for AUD in primary care, in a setting where the availability of treatment was not constraining. It is also the first study to look at predictors of two specific types of evidence-based treatment. In addition to need, patient factors were important predictors of treatment utilization and differed by type of treatment received. This suggests that either treatment may not be delivered equitably or that patient preference may be an important factor in determining who gets what treatment. We also found that receiving BT was associated with subsequent use of XR-NTX and may be associated with a longer duration of XR-NTX treatment. Providers should consider these findings when considering ways to increase primary-care based AUD treatment.

Table 3.

Predictors of receipt of brief therapy among primary care patients with alcohol use disorder* (N = 290).

| 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Odds ratio | Low | High | P-value |

| Predisposing | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Male | 1.03 | 0.47 | 2.27 | 0.943 |

| White | 1.94 | 0.97 | 3.88 | 0.062 |

| Hispanic | ||||

| Married/living w partner | ||||

| High school education or more | 0.97 | 0.50 | 1.87 | 0.924 |

| Enabling/inhibiting resources | ||||

| Income over $20,000 per year | ||||

| Homeless | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.62 | 0.001 |

| Working full or part-time | ||||

| Ever talked to professional about alcohol | 2.57 | 1.28 | 5.16 | 0.008 |

| Received treatment for alcohol in past 12 months | ||||

| PHQ8 scale for depression | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.09 | 0.219 |

| Need | ||||

| Co-occurring diagnosis of opioid use disorder | ||||

| ER visit or overnight hospital stay in past 90 days | ||||

| Negative consequences from substance use | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.14 | 0.093 |

| Received XR-NTX | 4.34 | 1.79 | 10.54 | 0.001 |

Note: XR-NTX = Injectable Extended-Release Naltrexone; PHQ8 = eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale; ER = emergency room; CI = confidence interval.

A11 models included site and clinical trial enrollment group.

Acknowledgements

Alkermes provided long-acting injectable naltrexone at no charge to patients with alcohol use disorders who were prescribed the medication by their primary care physician. This arrangement was disclosed and approved by the National Institutes of Health project officer, as well as to the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee. The authors acknowledge all study participants and healthcare providers at the Venice Family Clinic for their contributions to and participation in the study. We also thank the RAND Survey Research Group, all the staff from Venice Family Clinic and Tiffany Hruby for their contributions to carrying the study. The authors also acknowledge the SUMMIT Scientific Advisory Board for their input on the study design.

Role of funding source

This research was funded by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)R01DA034266 (PI: Watkins). The National Institute on Drug Abuse had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared

References

- Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, Nordentoft M, Luchenski SA, Hartwell G, Tweed EJ, Lewer D, Vittal Katikireddi S, Hayward AC, 2017. Morbidity and mortality In homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 391, 241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Ivey MA, Habing B, Lynch KG, 2009. Reliability and validity of the alcohol short index of problems and a newly constructed drug short index of problems. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 70, 304–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM, 2008. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med. Care 46, 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Baumeister SE, 2013. Improving access to care In: Kominski GF (Ed.), Changing the S.S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle R, Frye MA, Brecher M, Paulsson B, Rajagopalan K, Palmer S, Degl’ Innocenti A , 2009. The psychometric validation of the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 165, 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggett TP, O’Connell JJ, Singer DE, Rigotti NA, 2010. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am. J. Public Health 100, 1326–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Epstein AJ, Fiellin DA, Fraenkel L, Busch SH, 2016. Estimating demand for primary care-based treatment for substance and alcohol use disorders. Addiction 111, 1376–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard KA, Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, Lobouvie EW, Bux DA, 2003. Assessing consequences of substance use: psychometric properties of the inventory of drug use consequences. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 17, 328–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb JF, Lee AK, Lapham GT, Oliver M, Ludman E, Achtmeyer C, Parrish R, Caldeiro RM, Lozano P, Richards JE, Bradley KA, 2017. Evaluation of a pilot implementation to integrate alcohol-related care within primary care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014. Excessive Drinking Is Draining the U.S. Economy. (Accessed on June 16, 2016). http://www.cdc.gov/features/alcoholconsumption/.

- Chartier KG, Miller K, Harris TR, Caetano R, 2016. A 10-year study of factors associated with alcohol treatment use and non-use in a US population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 160, 205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR, 2007. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 86, 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Duncan MH, Smart BF, Saxon AJ, Malone DK, Jackson TR, Ries RK, 2015. Extended-release naltrexone and harm reduction counseling for chronically homeless people with alcohol dependence. Subst. Abus 36, 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Grant BF, 2012. Factors associated with first utilization of different types of care for alcohol problems. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 73, 647–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veteran Affairs, Department of Defense (VA/DoD), 2015. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders. Version 3.0. (Accessed on February 18, 2018). http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf.

- DiClemente CC, Doyle SR, Donovan D, 2009. Predicting treatment seekers’ readiness to change their drinking behavior in the COMBINE Study. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 33, 879–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne EM, Burrell LE 2nd, Diggins AD, Whitehead NE, Latimer WW, 2015. Increased risk for substance use and health-related problems among homeless veterans. Am. J. Addict. 24, 676–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M, 2014. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet 384, 1529–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman RF, Svikis D, Montoya ID, Blaine J, 2004. Selection of a substance use disorder diagnostic instrument by the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 27, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelaye B, Tadesse MG, Williams MA, Fann JR, Vander Stoep A, Andrew Zhou XH, 2014. Assessing validity of a depression screening instrument in the absence of a gold standard. Ann. Epidemiol. 24, 527–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JE, Perron BE, Ilgen MA, Chermack ST, Ratliff S, Zivin K, 2010. Prevalence and correlates of specialty substance use disorder treatment for Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare System patients with high alcohol consumption. Drug Alcohol Depend. 112, 150–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA, 2015. Specialty substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction 110, 1404–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Colpe LJ, 2017. Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of US adults with mental health and substance use disorders. Health Aff. (Millwood) 36, 1739–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine JP, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC, 2006. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO world mental health surveys. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 15, 167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AHS, Kivlahan DR, Bowe T, Humphreys KN, 2010. Pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorders in the Veterans Health Administration. Psychiatr. Serv. 61, 392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood HJ, Zhang Y, Dall TM, Olaiya ST, Fagan NK, 2009. Economic implications of reduced binge drinking among the military health system’s TRICARE Prime plan beneficiaries. Mil. Med. 174, 728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzerling KG, Ober AJ, Lamp K, De Vries D, Watkins KE, 2016. SUMMIT: Procedures for Medication-assisted Treatment of Alcohol or Opioid Dependence in Primary Care (TL-148-NIDA). RAND Corporation, Santa Monica. CA. [Google Scholar]

- Holtyn AF, Jarvis BP, Subramaniam S, Wong CJ, Fingerhood M, Bigelow GE, Silverman K, 2017. An intensive assessment of alcohol use and emergency department utilization in homeless alcohol-dependent adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 178, 28–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen MA, Price AM, Burnett-Zeigler I, Perron B, Islam K, Bohnert AS, Zivin K, 2011. Longitudinal predictors of addictions treatment utilization in treatment-naive adults with alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 113, 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Bobashev G, Thomas K, Wines R, Kim MM, Shanahan E, Gass CE, Rowe CJ, Garbutt JC, 2014. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 311, 1889–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, Heather N, Saunders J, Burnand B, 2007. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev, CD004148.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanny D, Brewer RD, Mesnick JB, Paulozzi LJ, Naimi TS, Lu H, 2015. Vital signs: alcohol poisoning deaths - United States, 2010-2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 63, 1238–1242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel P, Sullivan G, Burnam A, Morton SC, Wenzel S, 1999. Utilization of mental health and substance abuse services among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Med. Care 37, 306–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, 2001. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS, 2001. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA 285, 200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano JV, Bertsch J, Salvador-Carulla L, Tomas JM, Fernandez A, Pinto-Meza A, Haro JM, Palao DJ, Serrano-Blanco A, 2010. Factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity of the Sheehan Disability Scale in a Spanish primary care sample. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 16, 895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery AE, Szymkowiak D, Marcus J, Howard P, Culhane DP, 2016. Homelessness, unsheltered status, and risk factors for mortality: findings from the 100,000 homes campaign. Public Health Rep. 131, 765–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy for State Health Policy, 2017. Integrating Substance Use Disorder Treatment and Primary Care. National Academy for State Health Policy, Portland, ME. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018. NIDA Drug Screening Tool: NIDA-modified ASSIST (NM ASSIST), undated. (Accessed on March 20, 2017). https://www.drugabuse.gov/nmassist/.

- Ober AJ, Watkins KE, Hunter SB, Lamp K, Lind M, Setodji CM, 2015. An organizational readiness intervention and randomized controlled trial to test strategies for implementing substance use disorder treatment into primary care: SUMMIT study protocol. Implement. Sci 10, 66.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwin RG, Garrison-Mogren R, Jacobs ML, Sonnefeld LJ, 1999. Retention of homeless clients in substance abuse treatment. Findings from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Cooperative Agreement Program. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 17, 45–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osilla KC, D’Amico EJ, Lind M, Ober AJ, Watkins KE, 2016. Brief Treatment for Substance Use Disorders: a Guide for Behavioral Health Providers (TL-147-NIDA). RAND Corporation, Santa Monica. CA. [Google Scholar]

- Park-Lee E, Lipari RN, Hedden SL, Kroutil LA, Porter JD, 2012. Receipt of Services for Substance Use and Mental Health Issues Among Adults: Results From the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. CBHSQ Data Review. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), Rockville, MD, pp. 1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penberthy JK, Hook JN, Vaughan MD, Davis DE, Wagley JN, Diclemente CC, Johnson BA, 2011. Impact of motivational changes on drinking outcomes in pharmacobehavioral treatment for alcohol dependence. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 35, 1694–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Allamani A, Elekes Z, Jakubczyk A, Manthey J, Probst C, Struzzo P, Della Vedova R, Gual A, Wojnar M, 2015a. Alcohol dependence and treatment utilization in Europe - a representative cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Fam. Pract 16, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Manthey J, Struzzo P, Gual A, Wojnar M, 2015b. Who receives treatment for alcohol use disorders in the European Union? A cross-sectional representative study in primary and specialized health care. Eur. Psychiatry 30, 885–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Anderson P, Manthey J, Shield KD, Struzzo P, Wojnar M, Gual A, 2016. Alcohol use disorders in primary health care: What do we know and where do we go? Alcohol Alcohol. 51, 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M, Rehm J, 2013. Alcohol use disorders and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 108, 1562–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD, 2015. 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. Am. J. Prev. Med 49, e73–e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA, 2016. NSDUH Data Review. (Accessed on February 16, 2018). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR2-2015/NSDUH-FFR2-2015.htm.

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, 1992. Timeline follow-Back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption In: Litten RZ, Allen JP (Eds.), Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spithoff S, Kahan M, 2015. Paradigm shift: moving the management of alcohol use disorders from specialized care to primary care. Can. Fam. Phys. 61 (491–493), 495–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse Policy Research Program, 2018. Policy Brief: Substance Abuse Treatment Benefits and Costs, undated. Accessed on February 16, 2018. https://www.saprp.org/knowledgeassets/knowledge_brief.cfm?KAID = 1.

- Vaeth PA, Wang-Schweig M, Caetano R, 2017. Drinking, alcohol use disorder, and treatment access and utilization among U.S. Racial/ethnic groups. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 41, 6–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verissimo AD, Grella CE, 2017. Influence of gender and race/ethnicity on perceived barriers to help-seeking for alcohol or drug problems. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 75, 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, Lind M, Setodji C, Osilla KC, Hunter SB, McCullough CM, Becker K, Iyiewuare PO, Diamant A, Heinzerling K, Pincus HA, 2017. Collaborative care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: the SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med 177, 1480–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Matzger H, Tam T, Schmidt L, 2002. Who goes to alcohol and drug treatment? Understanding utilization within the context of insurance. J. Stud. Alcohol 63, 673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SL, Burnam MA, Koegel P, Morton SC, Miu A, Jinnett KJ, Sullivan JG, 2001. Access to inpatient or residential substance abuse treatment among homeless adults with alcohol or other drug use disorders. Med. Care 39, 1158–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EC, Gupta S Rubinsky AD, Glass JE, Jones-Webb R, Bensley KM, Harris AHS, 2017. Variation in receipt of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorders across racial/ethnic groups: a national study in the US Veterans Health Administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. 178, 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon YH, Yi HY, 2012. Surveillance Report #93: Liver Cirrhosis Mortality in the United States. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda, MD, pp. 1970–2009. [Google Scholar]