Abstract

A critical property of a prophylactic HIV vaccine is likely to be its ability to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs). BnAbs typically have multiple unusual features and are generated in a fraction of HIV-infected individuals through complex pathways. Current vaccine design approaches seek to trigger quite rare B cell precursors and then steer affinity maturation toward bnAbs in a multi-stage multi-component immunization approach. These vaccine design strategies have been facilitated by molecular descriptions of bnAb interactions with stabilized HIV trimers, the use of an array of sophisticated approaches for immunogen design, the development of novel animal models for immunogen evaluation and advanced technologies to interrogate Ab responses. In this review, we will discuss leading HIV bnAb vaccine immunogens, immunization strategies and future improvements.

Introduction

A prophylactic vaccine that can induce protective antibodies against HIV is paramount for controlling the HIV pandemic, which remains a major global health problem. Although an HIV vaccine remains elusive, remarkable progress has been made over the last decade. This progress includes the isolation of more than 200 broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) from HIV infected donors, which have revealed critical vaccine targets on the envelope (Env) protein [1–7]. A second significant discovery was the stabilization and structural characterization of a recombinant soluble Env trimer that mimics native Env present on the viral surface [8,9]. The coupling of these bnAbs and the trimer with structural studies have immensely facilitated structure-guided immunogen design and have made the development of an HIV neutralizing antibody vaccine appear to be an achievable goal.

A relatively small fraction of HIV-infected humans elicit potent bnAb responses, which target the Env spike or trimer and are effective against a wide range of viral isolates [2]. Passive transfer of these bnAbs into non-human primates (NHPs) provides complete protection against mucosal challenge with the virus [2,10]. These proof-of-concept studies suggest that a vaccine that elicits bnAbs of sufficient breadth, potency and concentration may exhibit sterilizing HIV immunity in humans. However, classical vaccine approaches have failed to elicit bnAbs for multiple reasons, including sequence variation in Env, difficulties of accessing bnAb epitopes hidden beneath the canopy of the Env glycan shield and the unique genetic requirements that reduce the frequency of precursors encoding bnAbs [1–3,6,11–14]. Recent immunogen design strategies seek to tackle the obstacles outlined by adoption of a multi-stage vaccine approach, which involves priming by bnAb precursor targeting molecules to initiate appropriate B cell lineages followed by sequential and/or cocktail immunogen boosts to drive affinity maturation along pathways to bnAbs.

In this review, we will focus on current HIV bnAb immunogen design strategies, recent progress made in the development of animal models to evaluate potential vaccine candidates, advances in the technology to analyze antibody responses, and emerging concepts in understanding B cell developmental pathways that may facilitate HIV vaccine design strategies.

Approaches to design immunogens capable of inducing HIV bnAbs

Native Env trimer immunogens

A major immunogen design effort focuses on the stabilization of native-like soluble trimers (Figure 1A). The SOSIP.664 design platform, which links the gp120 and gp41 subunits by a disulfide bond and stabilizes the trimer in the pre-fusion state through an I559P substitution, is the lead strategy in this category [8,15–20]. In contrast, design approaches that incorporate a linker between gp120 and gp41 have also been employed [21–23]. These native-like trimers are particularly advantageous, because they sequester inter-protomer surfaces to occlude immunodominant, non-neutralizing epitopes while presenting broadly neutralizing epitopes, including quaternary sites. While previous immunizations with gp120 or non-native trimers have generally produced tier 1 nAb responses, but failed to induce autologous tier 2 neutralizing Ab titers. Immunizations in mice, rabbits, guinea pigs and NHPs with the BG505 SOSIP trimer have produced autologous tier 2 neutralizing responses, indicating the presentation to the humoral immune system of at least some elements of native structure [16,18–20]. However, these native trimer immunizations yielded responses with very limited or no neutralization breadth [16,18–20].

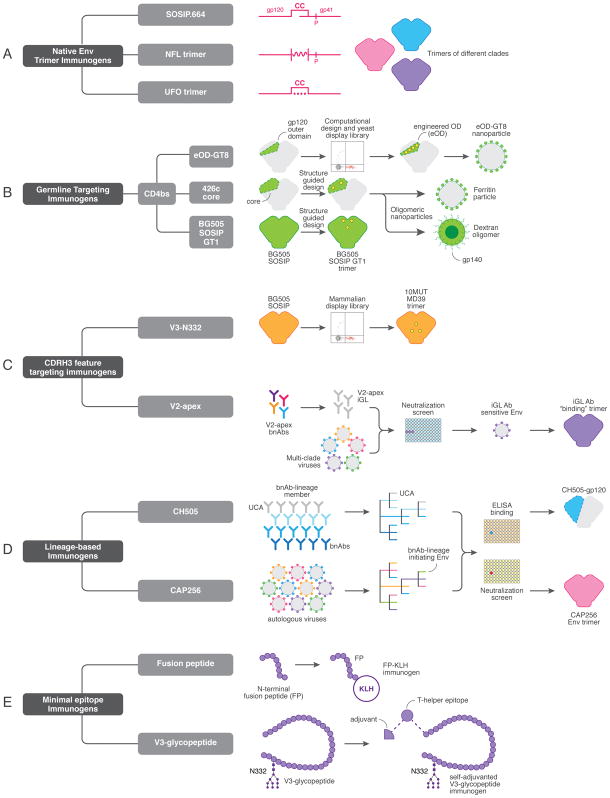

Figure 1. Immunogens that can form components of a neutralizing antibody-based HIV vaccine.

(a) Schematic showing native envelope trimer immunogens (SOSIP.664, native flexibly-linked (NFL) and uncleaved prefusion optimized (UFO) platforms), which form the basis of both priming and boosting immunization steps are shown. Trimers from multiple clades can be generated. (b) CD4 binding site (CD4bs) germline-targeting immunogens, including the engineered outer domain germline-targeting version 8 (eOD-GT8) immunogen (generated by computational approaches and refined through yeast-display and multimerized on nanoparticles), the 426c gp120 core, (which incorporates multiple glycan deletions around the CD4bs) and BG505 SOSIP-GT1 (SOSIP.664 modified to have enhanced binding of CD4bs germline-reverted antibodies) are illustrated. (c) Immunogens designed to select for antibodies with a long heavy chain complementarity determining region 3 (CDRH3), including the BG505 10MUT MD39 trimer to elicit PGT121-class V3-N332 bnAbs and trimers possessing “glycan holes” close to the trimer apex to generate V2 apex bnAbs. (d) Lineage-based immunogens, derived from virus-antibody co-evolution studies in donors CH505 and CAP256, are in development for the elicitation of CD4bs and V2 apex bnAbs. (e) Minimal epitope immunogens, including the N-terminal region of the fusion peptide (FP) fused to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) and V3-glycopeptides coupled to a T-helper epitope.

Studies of natural HIV infection demonstrated that exposure to viral variation within a bnAb epitope drives antibody maturation towards neutralization breadth [1,3,24]. Based on this, one approach to eliciting a protective nAb response incorporates trimeric immunogens derived from Envs representative of the global viral diversity within specific bnAb epitopes. In this approach, immunizations consisting of a cocktail of multi-clade Env-derived trimers would be administered repeatedly until bnAbs develop. These native trimer immunogen design approaches incorporate stabilizing mutations to increase thermostablity, prevent CD4-induced trimer opening, and improve immunogenicity by masking non-essential immunodominant epitopes [15,17,25,26].

bnAb germline-targeting immunogens

The concept of targeting germline-encoded features of bnAb precursors arose from the observations that inferred germline-reverted precursors (iGLs) of HIV bnAbs lack detectable binding affinity for native Env proteins [27], and that CD4 binding site (CD4bs) bnAbs isolated from multiple donors used a common germline-derived heavy chain immunoglobulin (Ig) gene, VH1-2*02 [14]. Accordingly, Jardine et al employed computational design coupled with a yeast display library platform to generate an outer domain (OD) molecule of Env gp120 with binding affinity for multiple VRC01-class bnAb precursors [13] (Figure 1B). The resulting germline-targeting molecule termed “eOD-GT6” was displayed on nanoparticles to increase multivalency for more efficient activation of VRC01 precursor B cells in vivo. Indeed, a successor to this molecule, eOD-GT8, successfully primed the appropriate precursors in a VRC01 GL knock-in (KI) mouse and enriched for VRC01–class precursors from naïve human B cells of HIV seronegative donors [28,29]. In addition, these eOD-GT8 primed responses displayed accumulation of somatic hypermutation along the VRC01-class maturation pathway. However, the lack of tier 2 neutralizing activity by these responses relied on their inability to tolerate the N276 glycan [add refs 32 and 33]. Trimeric boosting immunogens with increasing glycan complexity have been proposed to overcome the N267 hurdle to neutralization.

Although, eOD-GT8 immunogen can effectively prime the VRC01-like B cell precursors in appropriate animal models, its ability to select these germline B cell precursors varied substantially across different model systems [29–32]. While eOD-GT8 was most effective in the VRC01 GL KI mouse model, its ability to engage 3BNC60 germline expressing mouse BCRs was substantially lower and even weaker still in more competitive polyclonal mouse B cell immune systems that express either germline VH1-2*02 (excluding the CDRH3) or the entire human heavy chain Ig locus KI mouse models [31,32]. For example, in the human Ig transgenic mouse model (KymAb), a single immunization with eOD-GT8 revealed selection of only 1% of epitope specific VRC01-like B cell precursors of the total eOD-GT8 binders [31]. The variable efficiency of eOD-GT8 to engage VRC01-like B cell precursors from different animal models could be attributed to various factors including, its diverse affinity for VRC01 GLs and differences in the frequencies of appropriate precursors compared to off-target B cells. [32,33]. Based on these animal studies the eDO-GT8 priming immunogen will be tested in a Phase I clinical trial in 2018 to assess its ability to select VRC01-like precursors in humans.

In addition to eOD-GT8, other germline-targeting immunogens are being developed, including a core gp120 derived from a clade C Env, 426c, which binds VRC01-class germline precursors and primes germline receptor-expressing B cells in vivo [30,34], and modified versions of the BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer, which can bind multiple bnAb germline specificities [35] (Figure 1B). Overall, these strategies aim to activate VRC01-like precursor B cell receptors (BCRs) with a germline-targeting immunogen, followed by boosting with more native-like Env molecules to shepherd Ab responses along favorable bnAb developmental pathways [29–33].

CDRH3-feature targeting immunogens

Following the encouraging results of the VRC01 bnAb germline-targeting approach, a cell-surface mammalian display library platform was employed to select mutations within the BG505 SOSIP trimer backbone that would enable binding to iGL precursors of the PGT121-class of V3-N332 glycan-dependent bnAbs [36] (Figure 1C). Since bnAbs in this class use a long CDRH3 to bind the glycoprotein epitope at the base of the V3 loop and adjacent V1V2 loops, the authors created a glycan “hole” by removing specific glycans, altering variable loop lengths and substituting several residues within and around the epitope [12,36]. Sequential immunizations with four germline-targeting modified BG505 SOSIP trimers followed by boosts with a variable loop cocktail in a KI-mouse model expressing the PGT121 iGL BCR induced a nAb response with moderate breadth [37]. This five-month immunization scheme sequentially incorporated gradual changes to restore the native bnAb epitope, followed by diversification through variable loop length modifications in the final boosts. The study demonstrated that an HIV Env glycan-dependent nAb response could be triggered by a rationally designed sequential immunization strategy and represented the first example of a vaccine-induced cross-reactive nAb response in any animal model [37].

Another example of long CDRH3 germline feature targeting is apparent for V2 apex bnAbs, which bind to a glycoprotein epitope at the 3-fold axis of the trimer apex. These bnAbs use an unusually long anionic CDRH3 loop to reach the positively charged lysine-rich patch that forms the core protein epitope. Two independent studies by Andrabi et al., and Gorman et al. searched for Env sequences that could interact with iGL versions of the V2-apex bnAbs [38,39] (Figure 1C). Both studies identified viruses that were sensitive to neutralization by V2 apex bnAb iGL antibodies and the corresponding Envs could be adapted as soluble trimer immunogens. Notably, the majority of these Envs possessed uncommon glycan holes around the apex that may provide increased access to the core lysine patch at the V2-apex [20]. Trimer immunization in rabbits induced autologous neutralizing responses that largely targeted basic residues within the V2 region that forms the core bnAb epitope for human V2-apex bnAbs [20]. We have extended these V2 apex germline targeting efforts to chimeric V1V2 HIV trimers and an SIVcpzPtt Env (that shares the V2-apex bnAb epitope with HIV-1) based trimer designs. Administration of these trimers in a sequential prime/boost immunization strategy in a V2 apex CH01 UCA-expressing KI-mouse model induced Ab responses with some cross neutralization targeted to the V2 apex region (Andrabi et al, unpublished data).

The use of naturally existing or artificially created glycan holes on Env trimer immunogens to increase accessibility of immunoquiescent epitopes or to improve germline Ab binding has also been extended to the CD4bs bnAb epitope [35,40,41]. However, the glycan shield protects the underlying protein from immune recognition, therefore these immunogens may also increase accessibility of immunodominant, non-bnAb epitopes. Non-relevant B cells to these immunodominant epitopes would therefore present considerable competition for rare long CDRH3-bearing B cells. Nevertheless, sequential addition of these glycans in boosting immunogens may be able to eliminate unwanted B cell responses and encourage bnAb development.

Lineage-based immunogens

Approaches to understand bnAb development in natural infection have focused on identification of the ancestor precursor B cell, the corresponding viruses that initiated these precursor responses, and longitudinal tracing of their co-evolutionary developmental pathways. The ultimate goal is to use this information to design immunogens and strategies to recapitulate elicitation of these responses through vaccination. To date, virus and antibody co-evolution studies of HIV-infected individuals who developed bnAb responses to the CD4bs, V2 apex and V3-N332 bnAb sites have been described in great detail [1,3,6,42] (Figure 1D). These studies described the viral variants responsible for both the elicitation of rare bnAb precursors and the maturation of these responses to neutralization breadth.

The first of these studies described the development of a CD4bs bnAb lineage, CH103, presumably initiated by the founder Env, CH505, that exhibited detectable binding with the unmutated common ancestor (UCA) Ab [6]. Further, it was demonstrated that a helper B cell lineage, CH235, which itself became a bnAb lineage later, in this donor was critical for CH103 Ab bnAb development [1,4,6]. Unlike the VRC01-class CD4bs bnAbs, whose binding activity is in large part achieved by heavy chain V-gene encoded residues, the CH103 and CH235 CD4bs bnAbs are CDRH3-dominated [43]. The presence of the CD4bs bnAb site on gp120 subunit proteins is demonstrated by the high affinity binding of precursor and broad members of the CH103 and CH235 lineages. Therefore, Haynes and colleagues have defined a series of gp120 immunogens aimed at mimicking the evolution of the virus in the CH505 donor [1,44]. This approach includes priming with the founder virus-derived gp120 and boosting with various gp120s that incorporate the Env diversity observed during the development of the bnAb response.

Another strategy based on virus-antibody co-evolution in donor CAP256 is being pursued to elicit V2 apex bnAbs. In this case, the use of trimeric immunogens is required, as the V2 apex bnAb epitope is only present on native pre-fusion trimer and not on Env subunits. This approach will make use of bnAb-initiating Env immunogens to prime these responses followed by a series of sequential immunogens that incorporate diversity at key strand-C residues, as well as variable loop lengths and alternate glycosylations to train B cells to accumulate somatic mutations, including those specific to complex glycans around the V2-apex [3,24,45].

Lineage-based immunogen design and bnAb germline-targeting approaches may appear similar, however the former uses related antibodies at various points along the bnAb maturation pathway of a specific lineage to select for multiple sequential immunogens, while the latter employs structure-guided yeast display to identify immunogens with affinity to bnAb precursors.

Minimal epitope immunogens

Env trimers or monomeric gp120 immunogens display a large antigenic surface that can engage diverse BCRs. One strategy for immunofocusing to a very limited set of BCRs is to immunize with minimal Env constructs that incorporate a portion of a bnAb epitope. Constructs meeting this requirement are gp41-fusion peptides and molecules including the base of the V3 loop protein and critical glycans (Figure 1E).

One approach uses an 8-amino acid residue stretch of the N-terminus of a gp41 fusion peptide (FP) that binds to FP-targeting bnAb, VRC34 [5]. This FP, conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) through maleimide-linkage chemistry, was used to immunize mice, resulting in the induction of Abs that cross-neutralized ~20% of a global panel of viruses. (Kai Xu, Peter Kwong et al, Keystone-2018, unpublished). These initial FP-KLH immunizations mark important progress towards HIV vaccine-induced neutralizing responses in an unbiased B cell repertoire model. However further boosting sequentially with SOSIP trimers to encourage Ab recognition of key glycans surrounding the FP bnAb epitope will be critical to expand the neutralization breadth.

To design V3-glycopeptide based immunogens, another study used a chemoenzymatic method to synthesize and design a cyclic 33-mer gp120-V3 loop glycopeptide that represented a minimal epitope for the V3-glycan-dependent bnAbs, PGT128 and 10-1074 [46]. This V3-glycopeptide was further conjugated with a universal T-helper epitope and a Toll-like receptor 2 lipopeptide ligand (Pam3CSK4) to enhance immunogenicity. Immunizations in rabbits with this synthetic self-adjuvanted V3-glycopeptide elicited glycan-dependent antibody responses that were not neutralizing but displayed broader recognition of HIV-1 gp120s than the response induced by a non-glycosylated V3 peptide version.

Development of animal models for vaccine evaluation

Significant progress has been made over the past few years in the generation of immunoglobulin (Ig) knock-in (KI) mouse models that express the pre-rearranged V(D)J-encoding inferred germline genes of HIV bnAbs precursors to evaluate candidate immunogens (Figure 2A) [29,30,32,37,47]. Much of this activity has focused on VRC01-bnAb germline-KI models, but expansion to other bnAb precursors is in progress [37,48]. Immunizations in these models have yielded valuable insights, especially with respect to selection and early maturation of B cell precursors by germline-targeting immunogens. However, these KI mouse models have a selective advantage over unbiased B cell repertoires, as all or at least part of the bnAb precursor genes replace the natural mouse Ig genes. While these KI mouse studies have been informative, certain limitations, such as B cell receptor editing and peripheral anergy have complicated analysis of the experimental outcomes [47]. Nevertheless, precursor B cell adoptive transfers into wild-type animal models can provide models that more closely resemble those anticipated in humans and can provide estimates of the affinities of immunogens that may be required to trigger appropriate B cell lineages [49]. In addition, animal models with more complete human BCR repertoire diversity have been employed to assess the ability of germline-targeting immunogens to select appropriate precursors [31].

Figure 2. Animal models for immunogen evaluation and analysis of antibody responses.

(a) Five animal models (non-human primates, cows, guinea pigs, rabbits and mice) have been used to evaluate the immunogenicity of several current vaccine candidates. Within the mouse model, wild-type, immunoglobulin (Ig) gene knock-in mice (containing the rearranged Ig genes for the inferred unmutated common ancestor (UCA) versions of HIV broadly neutralizing antibodies), and mice transgenic for the human Ig locus have been used. The particular immunogen design platforms tested within each animal model system are shown. (b) Schematic depicting three critical technologies that have been used to evaluate vaccine-elicited antibody responses. Monoclonal antibodies, isolated by antigen-specific single B cell sorting and deep sequencing of B cell transcripts can then be used to identify many members of the corresponding B cell lineages. Finally, electron microscopy can be used to identify the epitopes of the vaccine-elicited antibodies. Information derived from the technologies can be fed back to support iterative immunogen design.

Animal models such as wild-type mice, guinea pigs, rabbits and NHPs have been mainly used to evaluate the immunogenicity of native-like trimer immunogens (Figure 2A). These studies have demonstrated induction of autologous tier 2 neutralizing responses by native-like trimers, which often, especially in rabbits, target immunodominant Env glycan holes, that may potentially distract from desired immune responses [16,18,19]. The responses, however, do vary across different model species. Interestingly, repeated immunization in cows with a single immunogen, the BG505 SOSIP trimer, induced rapid bnAb responses [50]. This contrasted sharply with the theory that sequential immunizations with different antigens will be required to generate bnAbs. However, these cow antibodies, which targeted the CD4bs, possessed ultra-long CDRH3 loops encoded by a VH-DH germline gene combination that is unique to the cow B cell repertoire. This ultra-long CDRH3 alone facilitated access to the CD4bs, which is otherwise sterically shielded from more traditional human bnAbs through glycosylation and oligomerization of the trimer [50]. Nevertheless, why immunization with a single immunogen produced continuous neutralization broadening rather than a narrower reactivity and higher affinity to the immunizing strain (BG505) is unclear.

Technological innovations to interrogate immune responses

The iterative design of HIV vaccine immunogens has been immensely facilitated by extensive characterization of the Abs isolated from both infected individuals and immunized animals. Technological advances in three areas have particularly contributed to this progress including, i) ability to rescue Ig transcripts from single B cells, ii) deep sequencing to identify bnAb lineages and trace their development through affinity maturation, and, iii) recent advances in structural biology tools (cryo-electron microscopy and x-ray crystallography) that have revealed critical interaction of Abs and antigen to facilitate structure-guided design strategies (Figure 2B). Historically, conventional approaches investigated vaccine-elicited Ab responses by ELISA or virus neutralization. However, such approaches are inadequate to deal with sequential staged immunization strategies that may only reveal the desired response such as virus neutralization at the final stage. It then becomes crucial to monitor progress at individual stages in the immunization strategy. Single B cell Ab isolation and next generation sequencing (NGS) of B cell expressed Ig transcripts made possible with the emergence of high-throughput sequencing platforms such as Illumina, have enabled the identification of the origin of B cell lineages and trace their development during affinity maturation in natural infection and in vaccination [3,6,31,33,42,51,52].

Recent advances in understanding the basis of B cell affinity maturation

The HIV Env trimer represents a complex antigenic surface, and the B cell affinity maturation processes to generate HIV bnAbs is intricate [3,6,24,45]. Therefore, understanding the biological basis of germinal center (GC) B cell selection to HIV immunogens at the primary and secondary stages of immune evaluation is important to design robust vaccine immunogens and strategies. Unfortunately, current understanding of antigen driven GC B cell selection comes from rather simple antigens and studies have only recently begun to investigate B cell responses to complex antigens like influenza hemagglutinin and bacillus anthracis protective antigen to observe a higher complexity of B cells responses [53,54]. Interestingly, these studies revealed that the GC B cell selection driven by complex antigens is more permissive to B cell clonal diversity and a range of BCR affinities than non-complex antigens described in earlier studies. Further studies of the complex antigen driven GC B cell selection as a function of change in antigenic surface under different immunization schemes at primary and secondary stages of immune responses will improve our understanding of how effective Ab responses are generated and facilitate design of better vaccine strategies.

Conclusions

The overall course of HIV vaccine development looks promising. One of the important questions to be addressed for germline-targeting immunogens is what are the affinity and frequency requirements to effectively trigger a rare bnAb precursor BCR. Multivalent display of immunogens [55–57] can activate precursor BCRs more efficiently and strategies that can reduce off-target B cell responses may guide immunofocused responses [58]. Deep mining of heathy human naïve B cell repertoires to determine precursor frequencies for each bnAb specificity will be an important consideration to devise optimal design strategies. Whether immunogen trafficking to secondary lymphoid follicles can be enhanced by immune complexes is an area of growing interest [59]. Also, a deeper understanding of GC B cell selection and Tfh biology for complex antigens at the primary and secondary immunization stages will be critical for developing more effective vaccine strategies. Finally, a multi-stage HIV vaccine will require manufacturing of several HIV vaccine immunogens, setting up of human clinical trials and an extensive pipeline for analysis of the immune responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology and Immunogen Discovery Grant UM1AI100663) (to D.R.B); the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) through the Neutralizing Antibody Consortium SFP1849 (D.R.B.); the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard (D.R.B.). This study was made possible by the generous support of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery (CAVD, OPP115782 and OPP1084519) and the American people through USAID. We thank Christina Corbaci for her help in the preparation of figures and members of our laboratory for helpful suggestions.

References

- 1.Bonsignori M, Zhou T, Sheng Z, Chen L, Gao F, Joyce MG, Ozorowski G, Chuang GY, Schramm CA, Wiehe K, et al. Maturation Pathway from Germline to Broad HIV-1 Neutralizer of a CD4-Mimic Antibody. Cell. 2016;165:449–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton DR, Hangartner L. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies to HIV and Their Role in Vaccine Design. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:635–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doria-Rose NA, Schramm CA, Gorman J, Moore PL, Bhiman JN, DeKosky BJ, Ernandes MJ, Georgiev IS, Kim HJ, Pancera M, et al. Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2014;509:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao F, Bonsignori M, Liao HX, Kumar A, Xia SM, Lu X, Cai F, Hwang KK, Song H, Zhou T, et al. Cooperation of B cell lineages in induction of HIV-1-broadly neutralizing antibodies. Cell. 2014;158:481–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong R, Xu K, Zhou T, Acharya P, Lemmin T, Liu K, Ozorowski G, Soto C, Taft JD, Bailer RT, et al. Fusion peptide of HIV-1 as a site of vulnerability to neutralizing antibody. Science. 2016;352:828–833. doi: 10.1126/science.aae0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao HX, Lynch R, Zhou T, Gao F, Alam SM, Boyd SD, Fire AZ, Roskin KM, Schramm CA, Zhang Z, et al. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature. 2013;496:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, et al. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science. 2009;326:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward AB, Wilson IA. The HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein structure: nailing down a moving target. Immunol Rev. 2017;275:21–32. doi: 10.1111/imr.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, et al. Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1477–1483. doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pegu A, Hessell AJ, Mascola JR, Haigwood NL. Use of broadly neutralizing antibodies for HIV-1 prevention. Immunol Rev. 2017;275:296–312. doi: 10.1111/imr.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kepler TB, Liao HX, Alam SM, Bhaskarabhatla R, Zhang R, Yandava C, Stewart S, Anasti K, Kelsoe G, Parks R, et al. Immunoglobulin gene insertions and deletions in the affinity maturation of HIV-1 broadly reactive neutralizing antibodies. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garces F, Lee JH, de Val N, de la Pena AT, Kong L, Puchades C, Hua Y, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Moore JP, et al. Affinity Maturation of a Potent Family of HIV Antibodies Is Primarily Focused on Accommodating or Avoiding Glycans. Immunity. 2015;43:1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jardine J, Julien JP, Menis S, Ota T, Kalyuzhniy O, McGuire A, Sok D, Huang PS, MacPherson S, Jones M, et al. Rational HIV immunogen design to target specific germline B cell receptors. Science. 2013;340:711–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1234150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West AP, Jr, Diskin R, Nussenzweig MC, Bjorkman PJ. Structural basis for germ-line gene usage of a potent class of antibodies targeting the CD4-binding site of HIV-1 gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2083–2090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208984109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Taeye SW, Ozorowski G, Torrents de la Pena A, Guttman M, Julien JP, van den Kerkhof TL, Burger JA, Pritchard LK, Pugach P, Yasmeen A, et al. Immunogenicity of Stabilized HIV-1 Envelope Trimers with Reduced Exposure of Non-neutralizing Epitopes. Cell. 2015;163:1702–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klasse PJ, LaBranche CC, Ketas TJ, Ozorowski G, Cupo A, Pugach P, Ringe RP, Golabek M, van Gils MJ, Guttman M, et al. Sequential and Simultaneous Immunization of Rabbits with HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein SOSIP. 664 Trimers from Clades A, B and C. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005864. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulp DW, Steichen JM, Pauthner M, Hu X, Schiffner T, Liguori A, Cottrell CA, Havenar-Daughton C, Ozorowski G, Georgeson E, et al. Structure-based design of native-like HIV-1 envelope trimers to silence non-neutralizing epitopes and eliminate CD4 binding. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1655. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01549-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCoy LE, van Gils MJ, Ozorowski G, Messmer T, Briney B, Voss JE, Kulp DW, Macauley MS, Sok D, Pauthner M, et al. Holes in the Glycan Shield of the Native HIV Envelope Are a Target of Trimer-Elicited Neutralizing Antibodies. Cell Rep. 2016;16:2327–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanders RW, van Gils MJ, Derking R, Sok D, Ketas TJ, Burger JA, Ozorowski G, Cupo A, Simonich C, Goo L, et al. HIV-1 VACCINES. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies induced by native-like envelope trimers. Science. 2015;349:aac4223. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voss JE, Andrabi R, McCoy LE, de Val N, Fuller RP, Messmer T, Su CY, Sok D, Khan SN, Garces F, et al. Elicitation of Neutralizing Antibodies Targeting the V2 Apex of the HIV Envelope Trimer in a Wild-Type Animal Model. Cell Rep. 2017;21:222–235. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Georgiev IS, Joyce MG, Yang Y, Sastry M, Zhang B, Baxa U, Chen RE, Druz A, Lees CR, Narpala S, et al. Single-Chain Soluble BG505. SOSIP gp140 Trimers as Structural and Antigenic Mimics of Mature Closed HIV-1 Env. J Virol. 2015;89:5318–5329. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03451-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong L, He L, de Val N, Vora N, Morris CD, Azadnia P, Sok D, Zhou B, Burton DR, Ward AB, et al. Uncleaved prefusion-optimized gp140 trimers derived from analysis of HIV-1 envelope metastability. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12040. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma SK, de Val N, Bale S, Guenaga J, Tran K, Feng Y, Dubrovskaya V, Ward AB, Wyatt RT. Cleavage-independent HIV-1 Env trimers engineered as soluble native spike mimetics for vaccine design. Cell Rep. 2015;11:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhiman JN, Anthony C, Doria-Rose NA, Karimanzira O, Schramm CA, Khoza T, Kitchin D, Botha G, Gorman J, Garrett NJ, et al. Viral variants that initiate and drive maturation of V1V2-directed HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2015;21:1332–1336. doi: 10.1038/nm.3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng Y, Tran K, Bale S, Kumar S, Guenaga J, Wilson R, de Val N, Arendt H, DeStefano J, Ward AB, et al. Thermostability of Well-Ordered HIV Spikes Correlates with the Elicitation of Autologous Tier 2 Neutralizing Antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005767. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon YD, Pancera M, Acharya P, Georgiev IS, Crooks ET, Gorman J, Joyce MG, Guttman M, Ma X, Narpala S, et al. Crystal structure, conformational fixation and entry-related interactions of mature ligand-free HIV-1 Env. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao X, Chen W, Feng Y, Zhu Z, Prabakaran P, Wang Y, Zhang MY, Longo NS, Dimitrov DS. Germline-like predecessors of broadly neutralizing antibodies lack measurable binding to HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: implications for evasion of immune responses and design of vaccine immunogens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jardine JG, Kulp DW, Havenar-Daughton C, Sarkar A, Briney B, Sok D, Sesterhenn F, Ereno-Orbea J, Kalyuzhniy O, Deresa I, et al. HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody precursor B cells revealed by germline-targeting immunogen. Science. 2016;351:1458–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jardine JG, Ota T, Sok D, Pauthner M, Kulp DW, Kalyuzhniy O, Skog PD, Thinnes TC, Bhullar D, Briney B, et al. HIV-1 VACCINES. Priming a broadly neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1 using a germline-targeting immunogen. Science. 2015;349:156–161. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dosenovic P, von Boehmer L, Escolano A, Jardine J, Freund NT, Gitlin AD, McGuire AT, Kulp DW, Oliveira T, Scharf L, et al. Immunization for HIV-1 Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies in Human Ig Knockin Mice. Cell. 2015;161:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sok D, Briney B, Jardine JG, Kulp DW, Menis S, Pauthner M, Wood A, Lee EC, Le KM, Jones M, et al. Priming HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in human Ig loci transgenic mice. Science. 2016;353:1557–1560. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian M, Cheng C, Chen X, Duan H, Cheng HL, Dao M, Sheng Z, Kimble M, Wang L, Lin S, et al. Induction of HIV Neutralizing Antibody Lineages in Mice with Diverse Precursor Repertoires. Cell. 2016;166:1471–1484e1418. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Briney B, Sok D, Jardine JG, Kulp DW, Skog P, Menis S, Jacak R, Kalyuzhniy O, de Val N, Sesterhenn F, et al. Tailored Immunogens Direct Affinity Maturation toward HIV Neutralizing Antibodies. Cell. 2016;166:1459–1470e1411. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGuire AT, Hoot S, Dreyer AM, Lippy A, Stuart A, Cohen KW, Jardine J, Menis S, Scheid JF, West AP, et al. Engineering HIV envelope protein to activate germline B cell receptors of broadly neutralizing anti-CD4 binding site antibodies. J Exp Med. 2013;210:655–663. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medina-Ramirez M, Garces F, Escolano A, Skog P, de Taeye SW, Del Moral-Sanchez I, McGuire AT, Yasmeen A, Behrens AJ, Ozorowski G, et al. Design and crystal structure of a native-like HIV-1 envelope trimer that engages multiple broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in vivo. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2573–2590. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steichen JM, Kulp DW, Tokatlian T, Escolano A, Dosenovic P, Stanfield RL, McCoy LE, Ozorowski G, Hu X, Kalyuzhniy O, et al. HIV Vaccine Design to Target Germline Precursors of Glycan-Dependent Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Immunity. 2016;45:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escolano A, Steichen JM, Dosenovic P, Kulp DW, Golijanin J, Sok D, Freund NT, Gitlin AD, Oliveira T, Araki T, et al. Sequential Immunization Elicits Broadly Neutralizing Anti-HIV-1 Antibodies in Ig Knockin Mice. Cell. 2016;166:1445–1458e1412. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrabi R, Voss JE, Liang CH, Briney B, McCoy LE, Wu CY, Wong CH, Poignard P, Burton DR. Identification of Common Features in Prototype Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies to HIV Envelope V2 Apex to Facilitate Vaccine Design. Immunity. 2015;43:959–973. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorman J, Soto C, Yang MM, Davenport TM, Guttman M, Bailer RT, Chambers M, Chuang GY, DeKosky BJ, Doria-Rose NA, et al. Structures of HIV-1 Env V1V2 with broadly neutralizing antibodies reveal commonalities that enable vaccine design. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:81–90. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubrovskaya V, Guenaga J, de Val N, Wilson R, Feng Y, Movsesyan A, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Ward AB, Wyatt RT. Targeted N-glycan deletion at the receptor-binding site retains HIV Env NFL trimer integrity and accelerates the elicited antibody response. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006614. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou T, Doria-Rose NA, Cheng C, Stewart-Jones GBE, Chuang GY, Chambers M, Druz A, Geng H, McKee K, Kwon YD, et al. Quantification of the Impact of the HIV-1-Glycan Shield on Antibody Elicitation. Cell Rep. 2017;19:719–732. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacLeod DT, Choi NM, Briney B, Garces F, Ver LS, Landais E, Murrell B, Wrin T, Kilembe W, Liang CH, et al. Early Antibody Lineage Diversification and Independent Limb Maturation Lead to Broad HIV-1 Neutralization Targeting the Env High-Mannose Patch. Immunity. 2016;44:1215–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou T, Lynch RM, Chen L, Acharya P, Wu X, Doria-Rose NA, Joyce MG, Lingwood D, Soto C, Bailer RT, et al. Structural Repertoire of HIV-1-Neutralizing Antibodies Targeting the CD4 Supersite in 14 Donors. Cell. 2015;161:1280–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams WB, Zhang J, Jiang C, Nicely NI, Fera D, Luo K, Moody MA, Liao HX, Alam SM, Kepler TB, et al. Initiation of HIV neutralizing B cell lineages with sequential envelope immunizations. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1732. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01336-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrabi R, Su CY, Liang CH, Shivatare SS, Briney B, Voss JE, Nawazi SK, Wu CY, Wong CH, Burton DR. Glycans Function as Anchors for Antibodies and Help Drive HIV Broadly Neutralizing Antibody Development. Immunity. 2017;47:524–537e523. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai H, Orwenyo J, Giddens JP, Yang Q, Zhang R, LaBranche CC, Montefiori DC, Wang LX. Synthetic Three-Component HIV-1 V3 Glycopeptide Immunogens Induce Glycan-Dependent Antibody Responses. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:1513–1522e1514. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verkoczy L, Alt FW, Tian M. Human Ig knockin mice to study the development and regulation of HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies. Immunol Rev. 2017;275:89–107. doi: 10.1111/imr.12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders KO, Nicely NI, Wiehe K, Bonsignori M, Meyerhoff RR, Parks R, Walkowicz WE, Aussedat B, Wu NR, Cai F, et al. Vaccine Elicitation of High Mannose-Dependent Neutralizing Antibodies against the V3-Glycan Broadly Neutralizing Epitope in Nonhuman Primates. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2175–2188. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbott RK, Lee JH, Menis S, Skog P, Rossi M, Ota T, Kulp DW, Bhullar D, Kalyuzhniy O, Havenar-Daughton C, et al. Precursor Frequency and Affinity Determine B Cell Competitive Fitness in Germinal Centers, Tested with Germline-Targeting HIV Vaccine Immunogens. Immunity. 2018;48:133–146e136. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sok D, Le KM, Vadnais M, Saye-Francisco KL, Jardine JG, Torres JL, Berndsen ZT, Kong L, Stanfield R, Ruiz J, et al. Rapid elicitation of broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV by immunization in cows. Nature. 2017;548:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature23301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Havenar-Daughton C, Carnathan DG, Torrents de la Pena A, Pauthner M, Briney B, Reiss SM, Wood JS, Kaushik K, van Gils MJ, Rosales SL, et al. Direct Probing of Germinal Center Responses Reveals Immunological Features and Bottlenecks for Neutralizing Antibody Responses to HIV Env Trimer. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2195–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeKosky BJ, Ippolito GC, Deschner RP, Lavinder JJ, Wine Y, Rawlings BM, Varadarajan N, Giesecke C, Dorner T, Andrews SF, et al. High-throughput sequencing of the paired human immunoglobulin heavy and light chain repertoire. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:166–169. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuraoka M, Schmidt AG, Nojima T, Feng F, Watanabe A, Kitamura D, Harrison SC, Kepler TB, Kelsoe G. Complex Antigens Drive Permissive Clonal Selection in Germinal Centers. Immunity. 2016;44:542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tas JM, Mesin L, Pasqual G, Targ S, Jacobsen JT, Mano YM, Chen CS, Weill JC, Reynaud CA, Browne EP, et al. Visualizing antibody affinity maturation in germinal centers. Science. 2016;351:1048–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bale JB, Gonen S, Liu Y, Sheffler W, Ellis D, Thomas C, Cascio D, Yeates TO, Gonen T, King NP, et al. Accurate design of megadalton-scale two-component icosahedral protein complexes. Science. 2016;353:389–394. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ingale J, Stano A, Guenaga J, Sharma SK, Nemazee D, Zwick MB, Wyatt RT. High-Density Array of Well-Ordered HIV-1 Spikes on Synthetic Liposomal Nanoparticles Efficiently Activate B Cells. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1986–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He L, de Val N, Morris CD, Vora N, Thinnes TC, Kong L, Azadnia P, Sok D, Zhou B, Burton DR, et al. Presenting native-like trimeric HIV-1 antigens with self-assembling nanoparticles. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12041. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S, Mata-Fink J, Kriegsman B, Hanson M, Irvine DJ, Eisen HN, Burton DR, Wittrup KD, Kardar M, Chakraborty AK. Manipulating the selection forces during affinity maturation to generate cross-reactive HIV antibodies. Cell. 2015;160:785–797. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang TT, Maamary J, Tan GS, Bournazos S, Davis CW, Krammer F, Schlesinger SJ, Palese P, Ahmed R, Ravetch JV. Anti-HA Glycoforms Drive B Cell Affinity Selection and Determine Influenza Vaccine Efficacy. Cell. 2015;162:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]