Abstract

The Himalayas are water tower for billions of people; however in recent years due to climate change several glaciers of Himalaya are receding or getting extinct which can lead to water scarcity and political tensions. Thus, it requires immediate attention and necessary evaluation of all the environmental parameters which can lead to conservation of Himalayan glaciers. This study is the first attempt to investigate the bacterial diversity from debris-free Changme Khang (CKG) and debris-cover Changme Khangpu (CK) glacier, North Sikkim, India. The abundance of culturable bacteria in CKG glaciers was 1.5 × 104 cells/mL and CK glacier 1.5 × 105 cells/mL. A total of 50 isolates were isolated from both the glacier under aerobic growth condition. The majority of the isolates from both the glaciers were psychrotolerant according to their growth temperature. Optimum growth temperatures of the isolates were between 15 and 20 °C, pH 6–8 and NaCl 0–2%. The phylogenetic studies of 16S RNA gene sequence suggest that, these 21 isolates can be assigned within four phyla/class, i.e., Firmicutes, Beta-proteobacteria, Gamma-proteobacteria and Actinobacteria. The dominant phyla were Firmicutes 71.42% followed by Actinobacteria 14.28%, Alpha-proteobacteria 9.52% and Beta-proteobacteria 4.76%. The isolate Bacillus thuringiensis strain CKG2 showed the highest protease activity (2.24 unit/mL/min). Considering the fast rate at which Himalayan glaciers are melting and availability of limited number of research, there is urgent need to study the microbial communities confined in such environments.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12088-018-0747-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Psychrophiles, Psychrotolerant, Changme Khang, Changme Khangpu, Glacier

Introduction

The Himalayas, termed now as the Third Pole, is not only the water tower for billions of people, but also the climate driving force for the entire Asia. The Himalaya still covers around 10% of ice (glaciers and ice niches), and cryospheric area which could be as much as ~ 20% more than solid glacier cover. Committee on Himalayan Glaciers, Hydrology, Climate Change, 2012 in its report “Himalayan Glaciers: Climate Change, Water Resources, and Water Security”, highlighted the potential impacts of climate change on Himalayan glaciers leading to water scarcity and which in turn could play an increasing role in political tensions. The factors that control and affect the Himalayan glacier dynamics is still poorly understood including the other peri-glacial/permafrost affected areas [1]. The World Meteorological Organization, 2012 has already reported that the polar areas have already undergone rapid decrease in snow and ice; thus releasing methane from permafrost regions causing rise in sea-level [2]. The role of cryosphere in moderating/controlling temperature through albedo effect is also not fully understood. The consequence of loss of the Himalayan cryosphere on the society invites immediate attention and necessary evaluation of all the environmental parameters so that a resilient and robust future plan could be drawn.

According to the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report 2007, warming of the climate system is occurring at unprecedented rates and an increase in greenhouse gas concentrations due to anthropogenic activities is responsible for most of this warming [3]. Microorganisms present in soil and water (frozen and liquid) contribute significantly to the production and consumption of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and nitric oxide (NO) which is further aggravated by microbes because of human activities such as waste disposal and agriculture. In the response to the increase in concentration of the greenhouse gases, microbes develop feedback system which might accelerate or slow down global warming, however, the extent of these effects are unknown [4]. Thus, understanding the role of these microbes in climate change might help us to determine whether they can be used to curb emissions or if they will push us even faster towards climatic disaster.

In recent years glacier studies attracted a lot of attentions as it is believed that glaciers and its micro-biota can be the best indicators of climate change and also source of several types of psychrophilic microorganisms [5, 6]. These microorganisms do not merely endure such extremely harsh conditions but permanently adapt to these environments, as most psychrophiles are incapable to grow at mesophilic conditions. The glaciers with structural differences in terms of physical and chemical properties may prove to be a source of novel cold-adapted bacteria [7, 8].

In contrast to general observation, a greater level of microbial diversity was observed in extremely cold habitats of Arctic and Antarctica regions [9]. However, the microbial diversity of Himalayan glacier has been less explored compared to other cold habitats around the globe. Some cultural bacterial diversity studies have been done on Himalayan glaciers. Zhang et al. have investigated the culturable bacterial diversity from Mt. Qomolangma (Everest) and the predominent phylum they found were Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Deinococcus [10, 11]. Similarly, Firmicutes, Alpha-proteobacteria, Gamma-proteobacteria and Actinobacteria were also reported from East Rongbuk Glacier, Mt. Everest ice core by Shen [12]. Similar types of bacteria were also isolated from the Muztag Ata Glacier, China by Xiang [13, 14]. The Eastern Himalayas is cataloging one of the major biodiversity hot spot regions in the world. Although the distribution and abundance of diverse bacterial species from sub-glacial and surface soil samples of certain parts of Himalayas have been reported, still there are many unexplored glaciers in Himalayan regions exist. In terms of microbiological studies in Indian Himalayan glaciers, very limited studies have been conducted. Thus, the present study aimed at understanding the diversity and distribution of culturable bacteria in the Sikkim Himalayas. For, the same the two glaciers, i.e., Changme Khang (CKG) and Changme Khangpu (CK) glacier from North Sikkim, India were selected and microbiological studies were carried out.

Materials and Methods

Site Description

GPS Mapping was done through GPS MAP 78S, an automated Global Positioning device. It was used to determine the coordinates of the glacier study sites, elevation of the land and the atmospheric temperature. The coordinates were processed through the programmed software’s like Google Earth and Arc GIS for mapping (Supplementary (S) Fig. 1).

Sample Collection and Pretreatment

The sample was taken by drilling the surface of the glacier ice about 2 meters from Changme Khangpu (CK) glacier and Changme Khang (CKG) glacier accumulation zone, North Sikkim (Supplementary (S) Fig. 2a, b) and immediately transported to the laboratory. The glacier ice core sample was processed and cut into small pieces about 6 inches and were kept for storage in the freezer at − 20 °C. The aseptic measures were taken and the glacier ice core samples were cut with a sterilized saw-tooth knife and around 5 mm annulus was discarded. The remaining inner core was rinsed with cold ethanol (4 °C; 95%), and finally with cold (4 °C) autoclaved water. The glacier ice core samples were placed in the sterile containers and melted at 4 °C incubator. These handling procedures were undertaken at temperatures below 20 °C aseptically using positive pressure laminar flow hood as described by Zhang [15].

Isolation and Cultivation of Psychrophilic Bacteria

200 µL of thawed glacial ice core melt water from each glacier inner ice core sample was directly spread on Luria–Bertani Agar (LBA) and Antarctica Bacterial Media (ABM), and then the cultures were incubated at 15 °C for 3 weeks. 200 µL of thawed glacial ice core melt water sample was enriched in 250 mL conical flask containing 50 mL Luria–Bertani broth and was incubated at 15 °C for 14 days in shaker incubator cum shaker at 120 rpm. After enrichment, the culture was spread plated on LBA and ABM agar media and incubated for 3 weeks at 15 °C until the colonies became visible. Morphologically different colonies were selected and sub-cultured by standard streak plate method. A total of 50 pure isolates were isolated from CK and CKG glacier. The pure bacterial isolates were cryopreserved at − 80 °C in 40% glycerol.

Physicochemical Characterization

The temperature dependent growth profile of the isolates were checked in Luria–Bertani broth at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 40 °C in incubator, and growth was measured by taking optical density (O.D.) at 600 nm in spectrophotometer (Lamda 25 UV/VIS, Perkin Elmer, USA). Similarly, NaCl dependent growth profile was checked at different concentrations of NaCl (0, 1 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10%) in Luria–Bertani broth incubated at 15 °C incubator. pH dependent growth profile was checked at different pH [16].

Cold-Active Extra Cellular Enzyme Activity

Amylase and protease enzyme activities were tested qualitatively using agar plates containing the specific substrate and incubating it at 15 °C for 10–15 days [17, 18].

Measurement of Protease Activity

The protease positive cultures were inoculated in M2 media containing 1% glucose, 0.5% peptone, 0.3% yeast extract, 0.02% MgCl2, 0.04% CaCl2 at pH 7.0 and incubated on a 15 °C rotary shaker at 180 rpm for 8 days. The protease activity was determined by the method of Ramakrishna, 1988 using Azocasein (Sigma Aldrich, USA) as substrate [19] and enzyme activity was measured at 650 nm in spectrophotometer (Lamda 25 UV/VIS, Perkin Elmer, USA). One unit of protease is defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyses the release of 1 µmol of l-Tyrosine per min under the above assay conditions.

DNA Extraction, Amplification and Identification

A total of 21 isolates were chosen for DNA extraction and sequencing. Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted by QIAamp kit according to the manufacturer protocol (QIAGEN, India). 16S rRNA genes were PCR amplified using the universal bacterial primer 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (CGGTTAC CTTGTTACGACTT-3′). PCR was carried out in a final volume of 50 µL using 2 µL template DNA, 2 µL MgCl2, 4 µL each dNTP, 1 µL each primer, 1 µL taq DNA polymerase, and 33 µL ddH2O. Reactions were performed in the thermo cycler (BioRAD) with the following reaction conditions; 94 °C for 5 min for initial denaturation followed by 30 cycle of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min, and the final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

The PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR clean up system kit (QIAGEN, India) and sequenced by ABI Applied Biosystems (3500 Genetic Analyzer) using each universal primer i.e., 27F and 1492R. The sequences were assembled and aligned using Codon Code Aligner software. The sequences were identified using nucleotide blast (NCBI search tool) and phylogenetic tree was created by using neighbor joining method [20]. The identified sequences were submitted to NCBI gene bank in order to get accession numbers.

Statistical Analysis

Assessment of the culturable bacterial diversity of five Himalayan glaciers (Roungbuk glacier, Changme Khangpu glacier, Changme Khang glacier, Muztag Ata glacier and Roopkund glacier) on the basis of predominant 16S rRNA gene sequences was carried out by Principal Component Analysis. Principal Component analysis (PCA) was done using XLSTAT 2014.03 software. Similarly, physicochemical correlations with bacterial diversity were analyzed by PCA. Bacterial diversity heat map was generated by ClustVis online software [21].

Results and Discussion

Site Description

Changme Khangpu (CK) and Changme Khangpu (CKG) glacier are located at Teesta river basin, in the upper catchment of one of its major tributaries, Lachung Chu (Lachung river), in the Sebu valley of North Sikkim, India. Both the glaciers originated from the southern slope of Gurudongmar peak. Changme Khang glacier is debris-free valley type glacier where as Changme Khangpu is a debris-cover valley type glacier trending north south, having a length of 5.87 km and width vary from 0.6 to 1 km Changme. These glaciers are located at latitude 27°58′N; longitude 88°42′E (CK) and latitude 27°56′N; longitude 88°39′E (CKG) glacier (Fig. 1). The melt water of these glacier feeds into Sebu Chu, a tributary of Lachung Chu, at Lachung North Sikkim, India [Supplementary (S) Fig. 1, 2a, b].

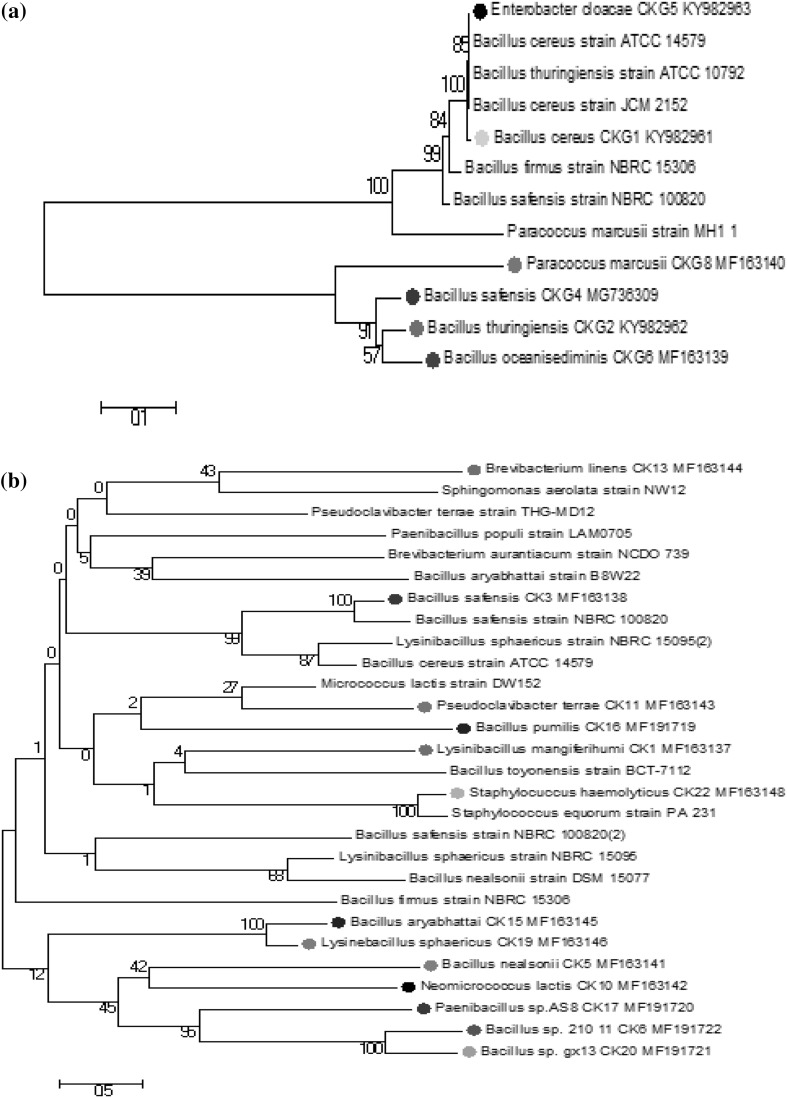

Fig. 1.

a, b Phylogenetic tree of Changme Khang and Changme Khangpu isolates. Neighbor-joining trees showing the phylogenetic relationships of bacteria 16S rRNA gene sequences from a Changme Khang glacier and b Changme Khangpu glacier ice core to closely related sequences from the GenBank database

Isolation of Psychrophilic Bacteria

A total of 50 bacteria were isolates from Changme Khangpu glacier and Changme Khang glacier on Luria–Bertani Agar (LBA) and Antarctica Bacterial Medium (ABM) at 15 °C. The abundance of culturable bacteria in Changme Khang glacier was 1.5 × 104 cells/mL and Changme Khangpu glacier 1.5 × 105 cells/mL.

Morphological and Biochemical Characterization of the Isolates

Based on colony morphology, 21 bacterial isolates, i.e., six bacterial isolates from Changme Khangpu glacier and fifteen isolates from Changme Khang glacier were selected for further analysis. The selection and grouping was done on the basis of biochemical and morphological characterization. The 21 isolates were mostly off white and rod shaped, however few were yellow, orange and cocci in shape (S. Table 1). The Gram-staining result showed that most of the isolates were Gram-positive and few were Gram-negative (S. Table 1). Most of the isolates, i.e., 12 out of 15 isolates from CK and 4 out of 6 isolates from CKG were spore formers (S. Table 1).

Growth at Different: Temperature, pH and NaCl

Isolates were examined for their growth at different temperature ranges (0–40 °C) so as to find out the optimum temperature required for their growth. All the isolates showed good growth at 15 °C (S. Table 2), but among all the isolates, eight isolates (CK1, CK5, CK9, CK13, CK17, CK19 and CK21) showed the highest growth at 15 °C and thus it might be the optimum temperature for these bacteria. For other isolates it was found that they could tolerate a wide range of temperature from 0 to 30 °C as they showed growth within this range (S. Table 2). pH values are also significant in deciphering the physiology of bacteria. Depending up on the bacterial optimum pH conditions, they are classified as acidophiles and alkaliphiles. This characteristic feature was investigated for the isolates of Changme Khang and Changme Khangpu isolates. At pH 4 to pH6, CK5, CK19, CK20, CK21 and CK22 isolates showed growth, whereas, CK6, CK9, CK10, CK11, CK16, CK19, CK20, CKG1, CKG2, CKG4, CKG6 and CKG8 isolates showed growth at pH6 and pH8. Majority of the isolates showed maximum growth at either pH6 or pH8 (S. Table 2).

Some of the isolates (33%) showed optimum growth at 2 and 5% of NaCl, indicating that these isolates are salt tolerant, while majority of isolates preferred low concentrations of NaCl (S. Table 2). In active ecology of glacial environment, water is found in nuclei forms inside the glacier mass, the solutes around that environment diffuse to these active ecological environments and make it hypertonic condition [21]. The exposure of bacteria to such high salt concentration might lead to salt tolerance. Salt and low temperatures are necessary for the stability of the cellular structure of psychrophilic bacteria and lysis of bacterial cell can occur at low ionic strength [22].

Enzymatic Activity

The identified bacterial isolates, Bacillus safensis CKG4, Bacillus cereus strain CKG1 and Enterobacter cloacae CKG5 were positive for proteases enzymes. With the crude cell extract it was found that Bacillus thuringiensis strain CKG2 showed maximum protease activity, i.e., 2.24 Units/mL/min (S. Table 3). The production of extracellular proteases and amylases by psychrophilic bacteria on a commercial level is more valuable than any other enzymes used for biotechnological and industrial applications [23, 24]. Due to high catalytic activity at low temperature, cold adapted psychrophilic enzymes have the potency to offer novel application for biotechnological uses [25]. Carbohydrate fermentation test has shown that majority of the isolates were able to ferment simple sugar such as Arabinose, Glucose, Mannose, Maltose, Mannitol and Ribose, however, all the isolates were unable to ferment sugars such as Dextrose, Galactose, Cellubiose and Fructose as shown in S. Table 4.

Identification of Bacterial Isolates

A total of 21 bacteria were selected on the basis of morphology and biochemical characteristic and were further subjected to 16S rRNA sequence analysis. Sequence analysis using BLAST showed that majority of the isolates were Gram-positive bacteria compare to Gram-negative bacteria. On the basis of similarity criteria of at least 97% for the 16S rRNA gene sequence, 21 isolates distributed within four different phyla/classes: Firmicutes (Bacillus cereus, Bacillus thuringinensis, Bacillus safensis, Bacillus oceanisediminis, Lysinibacillus mangiferahumi, Bacillus nealsonii, Bervibacillus brevis, Bacillus aryabhattai, Bacillus pumilus, Paenibacillus populi, Lysinibacillus sphaericus, Bacillus sp. gx13, Staphylococcus haemolyticus and Bacillus sp. 210-11), Actinobacteria (Neomicrococcus lactis, Pseudoclavibacter terrae and Bervibacterium linens), Alpha-proteobacteria (Paracoccus marcusii and Sphingomonas sp. PDD-69b-4) and Gamma-proteobacteria (Enterobacter cloacae). A phylogenetic tree including a representative from each of glacier isolates and their closest relatives are shown in Fig. 1a, b. The sequence analysis showed that the phylum Firmicutes in both the glacier are dominant, particularly the genus Bacillus. It was found that 66.6% isolates of Changme Khang and 73.3% Changme Khangpu were Firmicutes, followed by Alpha-proteobacteria (16.6% Changme Khangpu and Changme Khang 6%), Gamma-proteobacteria were present in Changme Khang glacier only (16.6%) whereas Actinobacteria on the other hand present only in Changme Khang glacier (14.28%).

Our result is closely associated with the previous study by Shen, 2012 at East Rongbuk debris-cover glacier ice core, Mt. Everest. They showed that phylum Firmicute were dominant phyla followed by Actinobacteria [12]. These bacteria are known to be resistant to extreme environments, including cryo-habitats such as ice sheet, permafrost, glaciers, sea ice and hot spring [10]. Their predominance might be due to one of several aspects, including (1) they are spore formers (2) their ability to utilize a wide range of organic substrates as their sole or principal sources of carbon and energy [23]. However, the survival of these bacteria in extremely stressful conditions is due to the formation of spores in Gram-positive bacteria as previously described by Boetius [26]. These findings strongly support to our study as most of our isolates were Gram-positive spore formers. Spore formation might help them to survive at low temperature, desiccation and uv radiation [27].

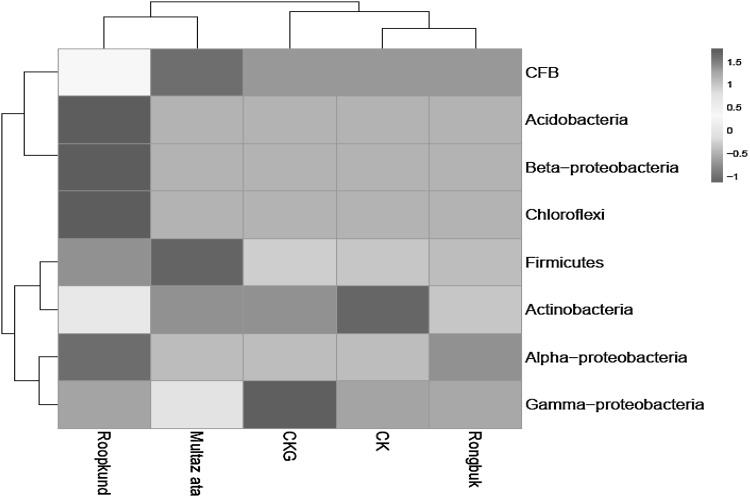

Heat Map Analysis

Heat Map analysis of culturable bacterial diversity among five different Himalayan glaciers (Rongbuk, Muztaz Ata, Roopkund, Changme Khang and Changme Khangpu glacier) showed that the phylum Firmicutes of Changme Khang, Changme Khangpu, Rongbuk and Roopkund glacier were positively correlated with each other while Multaz Ata glacier was negatively correlated. The phylum Actinobacteria of Changme Khangpu, Roopkund and Rongbuk glaciers indicated positive correlation among each other while Multaz Ata glacier isolates was negatively correlated. Only Gamma-proteobacteria of Multaz Ata showed positive correlation with Changme Khangpu while Changme Khangpu, Roopkund and Rongbuk glacier isolates were negatively correlated (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Bacterial diversity Heat map. A color scale heat-map showing culturable bacterial diversity assessment of five Himalayan glacier predominant 16S rRNA gene based bacterial sequences classified at Phylum level. Light green indicate higher abundance; light blue and dark blue indicate lower abundance. Roungbuk glacier, Changme Khangpu glacier (CK), Changme Khang glacier (CKG), Muztag Ata glacier and Roopkund glacier respectively (color figure online)

Principal Component Analysis of Bacterial Diversity

The principal component analysis of culturable bacterial diversity among five Himalayan glaciers (Roungbuk glacier, Changme Khangpu glacier (CK), Changme Khang glacier (CKG), Muztag Ata glacier and Roopkund glacier) were analyzed and the result showed that the glacier Changme Khang, Changme Khangpu and Rongbuk glacier were positively correlated with each other (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Principal component analysis of bacterial diversity. Principal component analysis (Distance Biplot): The first two PC1 and PC 2 are major components possessing 49.4 and 27.8% respectively. The graph shows the positive correlation between Rongbuk glacier, Changme Khangpu and Changme Khang glacier bacterial diversity

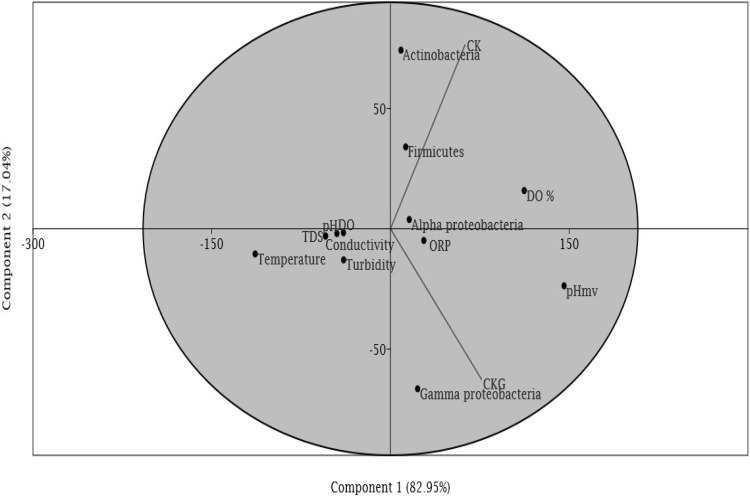

Principal Component Analysis of Physical Parameter and Bacterial Abundance

The principle component analyses (PCA) of physic-chemical parameter of glacier ice core melt water and bacterial diversity was correlated. Through PCA it can be inferred that phylum Alpha-proteobacteria of Changme Khang glacier showed positive correlation with dissolved oxygen whereas in Changme Khang glacier Gamma-proteobacteria and oxidation reduction potential was positively correlated while pH, conductivity, turbidity, temperature and total dissolved solid (TDS) was negatively correlated (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Principal component analysis of physical parameter and bacterial diversity. Principal component analysis (Distance Biplot): The first two components 1 and 2 are major components possessing 82.95 and 17.04% respectively. The graph shows that Alpha-proteobacteria of Changme Khang glacier showed positive correlation with DO whereas in Changme Khang glacier Gamma-proteobacteria and ORP were positively correlated with each other

Conclusion

To our understanding, this is the first report of the culturable bacterial diversity of psychrophilic bacteria from CK and CKG glacier of Sikkim. The results opened here support the idea that Himalayan glacial environments harbor rich microbial communities of poorly known diversities that validate to be studied before they die out. The sequence analysis showed that phylum Firmicutes in both the glaciers were the dominant (in particular to the Bacillus genus) with 66.6% in Changme Khang and 73.3% in Changme Khangpu glacier followed by Alpha-Proteobacteria (6% Changme Khang; Changme Khang 16.6%), Gamma-proteobacteria were present only in Changme Khang glacier (16.6%) whereas Actinobacteria on the other hand present in Changme Khang glacier only (14.28%). Our result is closely associated with the previous study by Shen, 2012 at East Rongbuk debris-cover glacier ice core, Mt. Everest. They showed that phylum Firmicute were dominant phyla followed by Actinobacteria in an debris-covered glacier. Protease enzyme produce by Bacillus thuringiensis strain CKG2 from crude cell extract, showed the activity of 2.24 Units/mL/min. The study of these psychrophilic bacterial and their enzymes will be useful to develop desired microbial consortium for organic waste treatment at cold regions and also they may find applications in other industries.

Finally, considering the rate of melting of glaciers and elevated frequency of multiple antibiotic resistances against therapeutic antibiotics exhibited by the glacial bacteria, their reactivation and exposure and transfer of their genetic element (horizontal gene transfer), could be considered a potential threat to human, plant and animal health. More effort shall be needed in near future to curb their potential threats.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Microbiology, Sikkim University for providing laboratory facilities. Thanks to DST (IUCCC) for providing JRF fellowship to MTS and Forest Department, Govt. of Sikkim for providing research permit and access.

Authors Contribution

NT designed the study, reviewed and edited manuscript, MTS did the experimental works, analysis and prepared the manuscript, INN and SD contributed in growth profiling experiments.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of Interests.

Contributor Information

Mingma Thundu Sherpa, Email: mingmasherpa8@gmail.com.

Ishfaq Nabi Najar, Email: urooj.ishfaq@gmail.com.

Sayak Das, Email: sayakdas2002@gmail.com.

Nagendra Thakur, Email: nthakur@cus.ac.in.

References

- 1.Byers A (2012) Committee on Himalayan Glaciers, hydrology, climate change, and implications for water security. The National Academies Press, Washington, pp 78–103. https://www.nap.edu/initiative/committee

- 2.Jarraud M (2012) WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2012. In: World meteorological organization, Geneva 2, Switzerland, pp 55–67. https://library.wmo.int/

- 3.Petschel G (2007) Mitigation of climate change: contribution of working group III to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental panel on climate change. In: Netherlands environmental assessment agency, Netherland. pp 71–76. https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment

- 4.Gupta C, Prakash DG. Role of microbes in combating global warming. Int J Pharm Sci Lett. 2014;4:359–363. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavicchioli R, Charlton T, Ertan H, Mohd Omar S, Siddiqui KS, Williams TJ. Biotechnological uses of enzymes from psychrophiles. Microb Biotechnol. 2002;4:449–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raman KV, Singh L, Dhaked R. Botechnological application of psychrophiles and their habitat to low temperature. J Sci Indian Res. 2000;59:87–101. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bottos EM, Vincent WF, Greer CW, Whyte LG. Prokaryotic diversity of arctic ice shelf microbial mats. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:950–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perreault NN, Andersen DT, Pollard WH, Greer C. Characterization of the prokaryotic diversity in cold saline perennial springs of the Canadian high Arctic. J Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1532–1543. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01729-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowman JP, Rea SM, McCammon SA, McMeekin TA. Diversity and community structure within anoxic sediment from marine salinity meromictic lakes and a coastal meromictic marine basin, Vestfold Hills, Eastern Antarctica. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2:227–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Yao T, Jiao N, Kang SH. Culturable bacteria in glacial meltwater at 6350 m on the East Rongbuk Glacier, Mount Everest. Extremophiles. 2009;13:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s00792-008-0200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong S, Zhang H, Yang W. Bacteria recovered from a high-altitude, tropical glacier in Venezuelan Andes. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;3:931–941. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen L, Yao T, Xu B, Wang H, Jiao N, Kang S. Variation of culturable bacteria along depth in the East Rongbuk ice core, Mt. Everest. Geosci Front. 2012;3:327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.gsf.2011.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiang S, Yao T, An L, Xu B. 16S rRNA sequences and differences in bacteria isolated from the Muztag Ata Glacier at increasing depths. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4619–4627. doi: 10.1007/BF02931042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang SR, Yao TD, An LZ, Xu BQ, Li Z, Wu GJ. Bacterial diversity in malan ice core from the Tibetan Plateau. Folia Microbiology. 2004;49:269–275. doi: 10.1007/BF02931042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X. Diversity of 16S rDNA and environmental factor influencing microorganisms in Malan ice core. Chin Sci Bull. 2003;48:1146–1152. doi: 10.1360/02wd0409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rafiq M, Hayat M, Anesio AM, Jamil SUU, Hassan N, Shah AA, Hasan F. Recovery of metallo-tolerant and antibiotic resistant psychrophilic bacteria from Siachen glacier, Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:56–61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu M, Fang Y, Li H, Liu WS. Isolation of a novel coldadapted amylase-producing bacterium and study of its enzyme production conditions. Ann Microbiol. 2010;60:557–563. doi: 10.1007/s13213-010-0090-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou MY, Chen XL, Zhao HL, Dang HY, Luan XW, Zhang XY, Zhou BC. Diversity of both the cultivable protease-producing bacteria and their extracellular proteases in the sediments of the South China Sea. Microb Ecol. 2009;58:582–590. doi: 10.1360/19301066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramakrishna TPM. Self association of a Chymotypsin: effect of amino acids. J Biosci. 1988;3:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1580–1596. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metsalu T, Vilo J. Clustvis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:566–570. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorv JSH, Rose DR, Glick BR. Bacterial ice crystal controlling proteins. Scientifica. 2014;3:1–20. doi: 10.1155/2014/976895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miteva V, Miteva V. Psychrophiles: from biodiversity to biotechnology. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 78–99. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rusell N. Towards a molecular understanding of cold activity of enzymes from psychrophiles. Extremophiles. 2000;4:83–90. doi: 10.1007/s007920050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niehaus F, Bertoldo C, Kahler MA. Extremophiles as a source of novel enzymes for industrial application. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;51:711–7729. doi: 10.1007/s002530051456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boetius A, Anesio AM, Deming JW, Mikucki JA, Rapp JZ. Microbial ecology of the cryosphere: sea ice and glacial habitats. Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:677–690. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yung PT, Shafaat HS, Connon SA, Ponce A. Quantification of viable endospores from a Greenland ice core. FEMS Microb Ecol. 2007;59:300–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.