Abstract

Cancer vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have recently been employed as immunotherapies for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Cancer vaccines for ESCC have yielded several promising results from investigator-initiated phase I and II clinical trials. Furthermore, a Randomized Controlled Trial as an adjuvant setting after curative surgery is in progress in Japan. On the other hand, ICI, anti-CTLA-4 mAb and anti-PD-1 mAb, have demonstrated tumor shrinkage and improved overall survival in patients with multiple cancer types. For ESCC, several clinical trials using anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb are underway with several recent promising results. In this review, cancer vaccines and ICI are discussed as novel therapeutic strategies for ESCC.

Keywords: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, immunotherapy, cancer vaccine, immune checkpoint inhibitors

Introduction

A multidisciplinary treatment, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, has been performed for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)1-3), however, the 5-year global survival is still poor at 30-40 %4). Therefore, it is an urgent task to further improve surgical techniques and chemoradiation strategies, and to develop novel therapeutic strategies including molecular target therapy and immunotherapy.

Recent studies have identified several immunogenic cancer antigens (ICA) expressed on ESCC cells5,6) and clinical trials of cancer vaccines using such ICA have been performed for ESCC. Although results are still challenging as a single agent7,8), there are several promising results from investigator-initiated phase I and II clinical trials. Furthermore, based on these encouraging results, a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) as an adjuvant setting after curative surgery is in progress in Japan9).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) such as anti-CTLA-4 mAb (ipilimumab) and anti-PD-1 mAb (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) have demonstrated tumor shrinkage and improved overall survival in patients with multiple cancer types, leading to renewed enthusiasm for cancer immunotherapy. For ESCC, several clinical trials using anti-PD-1 mAb, nivolumab, are in progress with several recent promising results9,10). Furthermore, an RCT has been initiated as a 1st line treatment for ESCC (CheckMate 649).

In this review, cancer vaccines and ICI are discussed as novel therapeutic strategies for ESCC.

Cancer vaccine

Mechanism of cancer vaccine

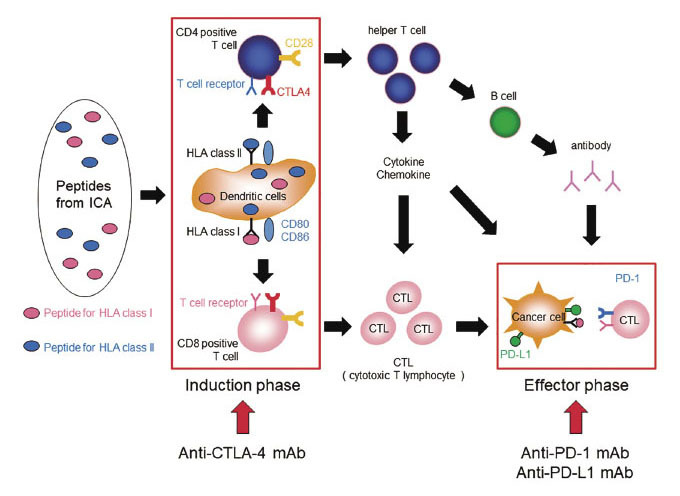

Since ICA were identified, translational research for the characterization of cancer antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) in cancer patients has been conducted globally. Cancer vaccine is a strategy that effectively induces cancer antigen-specific CTL using ICA in vivo (Fig. 1). Ideal characteristics of ICA for cancer vaccines are: (i) high immunogenicity, (ii) common and specific expression in cancer cells, and (iii) essential molecules for cancer cell survival. There are several types of ICA preparations such as: (i) synthetic tumor-associate antigens (TAA), (ii) whole tumor lysates, and (iii) TAA-encoding vectors. For cancer vaccination, we directly inoculate these ICA alone or dendritic cells (DC) loaded with TAAas well as fusion proteins11-13).

Fig. 1.

Schematic tumor immune response and mechanisms of ICI. Figure modified from Mimura K et al.48) with permission from Japanese Journal of Cancer and Chemotherapy.

Although many clinical cancer vaccine trials for malignant tumors including ESCC have been performed7-9,14-18), unfortunately, only one cell-based vaccine, sipuleucel-T (Provenge®), was clinically approved by FDA for patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer in 201019). To enhance the clinical effects of cancer vaccines, it may be necessary to develop new approaches such as the combination therapy with ICI to enhance effect of cancer antigen-specific CTL and the multiple ICA approach derived from the different target molecules to overcome heterogeneity of cancer cells20,21). We have recently began the development of a cancer vaccine with DC loaded with multiple TAA, which can simultaneously stimulate CD4- and CD8-positive T cells, since CD4-positive helper T cells enhance the induction and function of cancer antigen-specific CTL (Fig. 1).

Current status of cancer vaccine for ESCC

Clinical trials of cancer vaccines using peptides for esophageal cancer are summarized in Table 1. No cancer vaccine has been approved for clinical use for ESCC. Recently we have shown novel ICA including TTK protein kinase (TTK), lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus K (LY6K), insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II mRNA binding protein 3 (IMP-3), cell division cycle-associated protein 1 (CDCA1), and KH domain-containing protein overexpressed in cancer 1 (KOC1)7,8). Since these ICA, which are derived from different Cancer-Testis antigens, are highly and frequently expressed, and are essential molecules for survival and proliferation in ESCC, we thought that they would be promising targets for cancer vaccine against ESCC7,8). We therefore identified three HLA-A24-restricted immunodominant peptides that were derived from TTK, LY6K, and IMP3. We then performed phase I and II clinical trials of the cancer vaccine with a combination of these three peptides in HLA-A*2402 (+) patients with advanced ESCC who had failed to standard therapy7,8). In our phase II clinical trial, patients with immune response induced by the vaccination showed better prognosis than those with no immune response7).

Table 1.

List of clinical trials with peptide vaccine for Esophageal cancer

| Author/Sponsor | Agent | Traget | conditions | HLA type | IFA (incomplete freund’s adjuvant)/ combination |

Phase | Line | Number:

Esophageal cancer (total) |

UMIN-CTR ID or ClinicalTrial.gov, number | Recruitment Status |

| Shionogi & Co., Ltd. | S-588410 | DEPDCI, MPHOSPH1, LY6K, CDCA1, KOC1 | Esophageal cancer | A*24:02 | Montanide ISA-51 VG | III | Adjuvant | 270 | UMIN000016954 | Recruiting |

| Shionogi & Co., Ltd. | S-488410 | LY6K, CDCA1, KOC1 | Advanced or recurrent ESCC | (-) | ? | I/II | Salvage | 96 | UMIN000005161 | Completed |

| Kono K, et al. | (-) | TTK, LY6K, IMP-3 | Locally advanced, recurrent or/and metastatic ESCC who had faild for the standard therapy | (-) | Montanide ISA-51 | II | Salvage | 60 | NCT00995358 | Recruited |

| Yasuda T, et al. | (-) | LY6K, CDCA1, KOC1 | Thoracic ESCC who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by curative resection | (-) | Montanide ISA-51 | II | Adjuvant | 63 | UMIN000003557 | No longer recruiting |

| Kinki University Faculty of Medicine | (-) | LY6K, CDCA1, KOC1 | LN metastasis positive esophageal cancer without preoperative therapy | (-) | Montanide ISA-52 | II | Adjuvant | 60 | UMIN000003556 | Terminated |

| University of Tokyo | (-) | TTK | Advanced ESCC | A24 | ? | I | Salvage | 6 | UMIN000001014 | Terminated |

| Kono K, et al. | (-) | TTK, LY6K, IMP-3 | Locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic ESCC who had been resistant to the standard therapy | A*24:02 | Montanide ISA-51 | I | Salvage | 10 | NCT00682227 | Recruited |

| Iinuma H, et al. | (-) | TTK, LY6K, KOC1, VEGFR1, VEGFR2 | Unresectable chemo-naïve ESCC | A*24:02 | Montanide ISA-51

radiotherapy: 60 Gy Cisplatin: 40 mg/m2 5-fluorouracil: 400 mg/m2 |

I | Unresectable chemo-naïve | 11 | NCT00632333 | Recruited |

| Iwahashi M, et al. | (-) | TTK, LY6K | Advanced/metastatic ESCC | A*24:02 | CpG-7909 | I | Salvage | 9 | NCT00669292 | Recruited |

| Mie University | IMF-001

(CHP-NY-ESO-1) |

NY-ESO-1 | Curative resected esophageal cancer with NY-ESO-1 antigen expression | (-) | (-) | rII | Adjuvant | 70 | UMIN000007905 | Recruiting |

| Kageyama S, et al. | IMF-001

(CHP-NY-ESO-1) |

NY-ESO-1 | Advanced/metastatic esophageal cancer | (-) | (-) | I | Salvage | 25 | NCT01003808 | Recruited |

| Kakimi K, et al. | NY-ESO-1f | NY-ESO-1 | Advanced cancer expressed NY-ESO-1:

including six esophageal cancer patients |

(-) | Picibanil OK-432,

Montanide ISA-51 |

I | Salvage | 6 (10) | UMIN000001260 | Recruited |

| National Cancer Center Hospital East | HSP105-derived peptide vaccnine | HSP105 | Advanced esophageal cancer/ colo- rectal cancer | A*24:02 or 02:01 or 02:06 or 02:07 | (-) | I | Salvage | ? (15) | UMIN000017809 | No longer recruiting |

| Saito T, et al. | CHP-MAGE-A4 | MAGE-A4 | Advanced cancer expressed MAGE-4:

including 18 esophageal cancer patients |

(-) | (-) | I | Salvage | 18 (20) | UMIN000003188 | Recruited |

Based on the same strategy, two clinical trials of cancer vaccine with three immunodominant peptides derived from LY6K, CDCA1, and KOC1, are in progress as adjuvant setting. Yasuda T et al. reported that a group receiving cancer vaccine has a better relapse-free survival in comparison to a group not receiving cancer vaccine22) Furthermore, Shionogi, a pharmaceutical company in Japan, is performing a phase III clinical trial of cancer vaccine in an adjuvant setting after curative surgery for esophageal cancer to obtain an approval as a drug9).

ICI

Functional mechanism of ICI

In an interaction between T cells and cancer cells, the T-cell response is regulated by a balance between activating and inhibitory signals in T cells. These signals are currently called the immune checkpoints23,24). Two immune checkpoint receptors, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), have recently been actively investigated. Both receptors are expressed on T cells where they induce inhibitory signals (Fig. 1).

CTLA-4 counteracts and inhibits CD28, which is an activating T cell co-stimulatory receptor, and fundamentally regulates the induction phase of T cell activation25). Although CD28 signaling strongly enhances T cell receptor signaling and leads to activation of T cells, CTLA-4 inhibits the activity of CD28, resulting in inactivation of T cells25). In 2010, the FDA approved the anti-CTLA-4 mAb, ipilimumab, as the first ICI for metastatic melanoma26).

PD-1 interacts with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on cancer cells and immune cells. PD-1/PD-L1 signals reduce cytotoxic function of CTL and induce apoptosis of CTL27,28). PD-L1 is an inhibitory B7 family member and up-regulation of PD-L1 has been reported in various types of human cancer including ESCC and immune cells23,29,30). Currently, two anti-PD1 mAbs, nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are available for clinical use for several types of cancer. They have shown significant and durable responses in several types of refractory tumors including in 31% of patients with melanoma, 29% with kidney cancer and 17% with lung cancer31-33). Furthermore, recently, two anti-PD-L1 mAbs, avelumab and atezolizumab, are approved for clinical use in Japan. Avelumab is available for unresectable merkel cell carcinoma and atezolizumab is available for unresectable progressive / recurrent non-small cell lung cancer respectively.

CTL induction and infiltration in vivo

Since anti-CTLA-4 mAb mainly activates T cells in the induction phase and anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb enhances CTL function in the effector phase (Fig. 1), CTL induction and infiltration in vivo is very crucial to enhance the clinical effects of ICI. In order to efficiently induce CTL in vivo, ICA and activation of DC, which can phagocytize and present ICA, are regarded important.

Neoantigens have recently been proposed as candidates for ICA to efficiently induce CTL in vivo34). Neoantigens are formed by peptides that are entirely absent from the normal human genome; they are solely created by cancer specific DNA alterations in cancer cells, resulting in the formation of novel protein sequences. Several ICI clinical trials have been reported confirming the significant correlations between clinical response and burden of mutation-derived neoantigens, suggesting that a part of the cancer was eliminated by neoantigen specific CTL activated by ICI34).

The concept of immunogenic tumor cell death (ICD) was proposed by Apetoh et al.35). In ICD, DC were activated by danger signals such as high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and calreticulin released by dying cells. The activated DC could then efficiently phagocytize and present cancer antigens, resulting in CTL induction35). We showed that chemoradiation could induce up-regulation of local HMGB1 and cancer antigen-specific CTL in ESCC patients36). Furthermore, our in vitro study showed that HMGB1 was produced following chemoradiation in a panel of ESCC cell lines36). The abscopal effect is rare phenomenon where local irradiation on the tumor causes regression of metastases at sites distant from the irradiated area37). This effect is a rare phenomenon but has been shown in several types of malignant tumors, including melanoma, lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and renal cell carcinoma38,39). Although its mechanism has not been completely elucidated40), there is a possibility that the abscopal effect is induced by the ICD process.

Current status of ICI for ESCC

The clinical trials of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb for esophageal cancer are summarized in Table 2. Focusing on clinical trials for ESCC, there are phase II and III clinical trials of nivolumab. In the phase II clinical trial, patients with ESCC who were refractory or intolerant to standard chemotherapy were recruited (n=65) and the design was single-arm as a second line setting10). As a result of this trial, the objective response rate (complete response [CR] and partial response [PR]) and disease control rate (CR, PR, and stable disease [SD]) were seen in 14% and 42% of the enrolled patients, respectively, and the adverse event profile was acceptable10).

Table 2.

List of clinical trials with anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAbs for Esophageal cancer

| Traget | Agent | Sponsor / Collaborator | Condition | Arms | Phase | Line | Number | ClinicalTrial.gov, number,

UMIN-CTR ID, JapicCTI-No. |

Recruitment Status |

| PD-1 | Nivolumab (ONO-4538) | Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Bristol-Myers Squibb | Esophageal Cancer | Single-arm:nivolumab | II | Salvage | 65 | JapicCTI-142422 | Recruited |

| PD-1 | Nivolumab (ONO-4538) | Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd / Bristol-Myers Squibb | Esophageal Cancer | Nivolumab

Docetaxel or paclitaxel |

III | Salvage | 390 |

NCT02569242

JapicCTI-153026 |

Recruiting |

| PD-1 | Nivolumab (ONO-4538) | Bristol-Myers Squibb / Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd | Stage II/III carcinoma of the esophagus or gastroesophageal junction | Nivolumab

Placebo |

III | Adjuvant | 760 | NCT02743494 | Recruiting |

| PD-1 | Nivolumab (ONO-4538) | Bristol-Myers Squibb / Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd | Gastric Cancer

Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer *Cancer cannot be operated on and is advanced or has spread out. |

Nivolumab + ipilimumab

XELOX (oxaliplatin + capecitabine) FOLFOX (oxaliplatin + leucovorin + fluorouracil) Nivolumab + XELOX Nivolumab + FOLFOX |

III | 1st | 1266 | NCT02872116 | Recruiting |

| PD-1 | Nivolumab (ONO-4538) | Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center / Bristol-Myers Squibb | Operable Stage II/III Esophageal/Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer | Nivolumab + carboplatin/paclitaxel + radiation

Nivolumab + ipilimumab + carboplatin/paclitaxel + radiation |

I | Neoadjvant | 32 | NCT03044613 | Recruiting |

| PD-1 | Nivolumab (ONO-4538) | Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd / Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd | Locally advanced or metastatic Solid Tumor | Single-arm:

mogamulizumab + nivolumab |

I | Salvage | 108 | NCT02476123 | Active, not recruiting |

| PD-1 | Nivolumab (ONO-4539) | Osaka University / Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Clinical Study Support, Inc., Fiverings Co., Ltd. | Operable Gastric Cancer, Esophageal Cancer, Lung Cancer, Renal Cancer | Single-arm:

mogamulizumab + nivolumab |

I | Neoadjuvant | 18 |

NCT02946671

UMIN000021480 |

Recruiting |

| PD-1 | Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) | Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. | Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophagogastric Junction Carcinoma |

Single-arm:

pembrolizumab |

II | 3rd | 100 | NCT02559687 | Active, not recruiting |

| PD-1 | Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) | Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. | Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophagogastric Junction Carcinoma |

Pembrolizumab

Investigator’s choice of chemotherapy:paclitaxel, or docetaxel, or irinotecan |

III | 2nd | 720 | NCT02564263 | Recruiting |

| PD-1 | Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) | City of Hope Medical Center / National Cancer Institute (NCI) | Adenocarcinoma of the Gastroesophageal Junction Gastric Adenocarcinoma

Gastric Squamous Cell Carcinoma Metastatic Malingnant Neoplasm in the Stomach Stage IV Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Stage IV Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

Single-arm:

pembrolizumab + palliative external beam radiation therapy |

II | Salvage | 14 | NCT02830594 | Recruiting |

| PD-1 | Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) | Washington University School of Medicine / Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. | Untreated metastatic Esophageal Cancer | Single-arm:

pembrolizumab + radiation (brachytherapy) *brancytherapy=16 Gy delivered in 2 fractions of 8 Gy per fraction |

I | 1st | 15 | NCT02642809 | Recruiting |

| PD-L1 | Atezolizumab (MPDL3280A) | Genentech, Inc. | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors or hematologic malignancies (including esophageal cancer) | single-arm:atezolizumab | I | Salvage | 698 | NCT01375842 | Active, not recruiting |

| PD-L1 | Atezolizumab (MPDL3280A) | Academisch Medisch Centrum - University van Amsterdam (AMC-UvA) / UMC Utrecht | Stage II/III Esophageal Cancer

*adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or gastro esophageal juncion |

single-arm:atezolizumab + carboplatin + paclitaxel + radiation (23×1.8 Gy) | II | 1st | 40 | NCT03087864 | Recruiting |

| PD-L1 | Durvalumab (MEDI4736) | Samsung Medical Center | Esophageal Cancer | Durvalumab

Placebo |

rII | Adjuvant | 84 | NCT02520453 | Recruiting |

| PD-L1 | Durvalumab (MEDI4736) | Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research / AstraZeneca | Esophageal Cancer | Durvalumab + oxaliplatin + capecitabine

Durvalumab + tremelimumab + oxaliplatin + capecitabine Durvalumab + surgery + oxaliplatin + capecitabine Durvalumab + surgery + oxaliplatin + capecitabine + radiotherapy |

I/II | 1st | 75 | NCT02735239 | Recruiting |

Following the promising results from the phase II clinical trial of nivolumab for ESCC, a phase III clinical trial as a salvage setting was started. In total, 390 advanced or recurrent ESCC patients, who were refractory to 5FU + CDDP-based chemotherapy, were enrolled and randomly assigned into either a nivolumab or paclitaxel/docetaxel group (NCT02569242). The primary endpoint of this trial is overall survival (OS) and the results are expected to be released in 2020. Furthermore, enrollment is currently underway for a new RCT as a 1st line setting for ESCC (CheckMate 649). In this trial, inoperable advanced or recurrent ESCC patients will be randomly assigned into three groups: nivolumab + ipilimumab, 5FU + CDDP + nivolumab, and 5FU + CDDP.

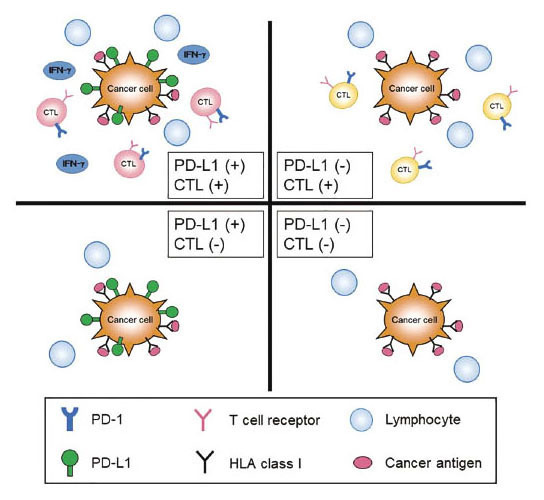

Next challenge of cancer immunotherapy for ESCC

It is assumed that anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb will be key drugs for immunotherapy for ESCC. As described above, anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb enhance CTL function in the effector phase (Fig. 1). If there are tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) in the tumor microenvironment, CTL should be present. From the view point of expected clinical effects of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb, several articles including ours suggested that the tumor microenvironment can be subclassified into 4 types: CTL(+) and PD-L1(+) on cancer cells, CTL(+) and PD-L1(-), CTL(-) and PD-L1(+), and CTL(-) and PD-L1(-) (Fig. 2)41,42). We speculate that optimum clinical effects of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb can be obtained from the tumor microenvironment like as CTL(+) and PD-L1(+). This suggests that it is important to increase CTL infiltration in the tumor microenvironment before administration of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb.

Fig. 2.

Four subclassifications of tumor microenvironments from the view point of expected clinical effects of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb. Figure modified from Mimura K et al.41 with permission from Japanese Journal of Cancer and Chemotherapy.

Anti-CTLA-4 mAb, cancer vaccine, and chemoradiation have a potential to induce CTL infiltration in vivo because anti-CTLA-4 mAb mainly activates T cells in the induction phase to induce CTL (Fig. 1) and the cancer vaccine induces cancer antigen-specific CTL. Furthermore, we showed that chemoradiation could induce cancer antigen-specific CTL in ESCC patients36). Some cytotoxic drugs or molecular target drugs are also thought to induce ICD, resulting in CTL induction43,44). In addition, since activated CTL produce IFN-γ, activated CTL in the tumor microenvironment could induce PD-L1 expression on cancer cells through the effect of IFN-γ. Our next challenge is the clinical development of combinatorial approaches, using anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb with treatments to induce CTL. In animal models and pre-clinical data, a strong synergy was observed between cancer vaccine and ICI, anti-CTLA-4 mAb and anti-PD-1 mAb45,46). Moreover, it was reported that a combination of anti-CTLA-4 mAb with anti-PD-1 mAb led to rapid tumor regression in almost a third of melanoma patients47).

Collectively, ESCC has biological characteristics suitable for immunotherapy, such as high frequency of neoantigens, radio-sensitive tumor, and several identification of ICA. We suggest that a combination of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 mAb with treatments to induce CTL including anti-CTLA-4 mAb, cancer vaccine, chemoradiation, and cytotoxic and/or molecular target drugs, may be an ideal and reasonable strategy for ESCC therapy.

Conflict of interest statement and ethical statement

All authors have no conflict of interest in this study. All procedures in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation at Fukushima Medical University and with the Helsinki Declaration.

References

- 1.Crosby T, Hurt CN, Falk S, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with oesophageal cancer (SCOPE1): a multicentre, phase 2/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol, 14: 627-637, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med, 366: 2074-2084, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariette C, Piessen G, Triboulet JP. Therapeutic strategies in oesophageal carcinoma: role of surgery and other modalities. Lancet Oncol, 8: 545-553, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer, 136: E359-386, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huppa JB, Davis MM. T-cell-antigen recognition and the immunological synapse. Nat Rev Immunol, 3: 973-983, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masopust D, Schenkel JM. The integration of T cell migration, differentiation and function. Nat Rev Immunol, 13: 309-320, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kono K, Iinuma H, Akutsu Y, et al. Multicenter, phase II clinical trial of cancer vaccination for advanced esophageal cancer with three peptides derived from novel cancer-testis antigens. J Transl Med, 10: 141, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kono K, Mizukami Y, Daigo Y, et al. Vaccination with multiple peptides derived from novel cancer-testis antigens can induce specific T-cell responses and clinical responses in advanced esophageal cancer. Cancer Sci, 100: 1502-1509, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima T, Doi T. Immunotherapy for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep, 19: 33, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kudo T, Hamamoto Y, Kato K, et al. Nivolumab treatment for oesophageal squamous-cell carcinoma: an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol, 18: 631-639, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tacken PJ, de Vries IJ, Torensma R, Figdor CG. Dendritic-cell immunotherapy: from ex vivo loading to in vivo targeting. Nat Rev Immunol, 7: 790-802, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonifaz LC, Bonnyay DP, Charalambous A, et al. In vivo targeting of antigens to maturing dendritic cells via the DEC-205 receptor improves T cell vaccination. J Exp Med, 199: 815-824, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aranda F, Vacchelli E, Eggermont A, et al. Trial Watch: Peptide vaccines in cancer therapy. Oncoimmunology, 2: e26621, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iinuma H, Fukushima R, Inaba T, et al. Phase I clinical study of multiple epitope peptide vaccine combined with chemoradiation therapy in esophageal cancer patients. J Transl Med, 12: 84, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwahashi M, Katsuda M, Nakamori M, et al. Vaccination with peptides derived from cancer-testis antigens in combination with CpG-7909 elicits strong specific CD8+ T cell response in patients with metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci, 101: 2510-2517, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kageyama S, Wada H, Muro K, et al. Dose-dependent effects of NY-ESO-1 protein vaccine complexed with cholesteryl pullulan (CHP-NY-ESO-1) on immune responses and survival benefits of esophageal cancer patients. J Transl Med, 11: 246, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakimi K, Isobe M, Uenaka A, et al. A phase I study of vaccination with NY-ESO-1f peptide mixed with Picibanil OK-432 and Montanide ISA-51 in patients with cancers expressing the NY-ESO-1 antigen. Int J Cancer, 129: 2836-2846, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito T, Wada H, Yamasaki M, et al. High expression of MAGE-A4 and MHC class I antigens in tumor cells and induction of MAGE-A4 immune responses are prognostic markers of CHP-MAGE-A4 cancer vaccine. Vaccine, 32: 5901-5907, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 363: 411-422, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cecco S, Muraro E, Giacomin E, et al. Cancer vaccines in phase II/III clinical trials: state of the art and future perspectives. Curr Cancer Drug Targets, 11: 85-102, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesterhuis WJ, Haanen JB, Punt CJ. Cancer immunotherapy--revisited. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 10: 591-600, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasuda T, Nishiki K, Yoshida K, et al. Cancer peptide vaccine to suppress postoperative recurrence in esophageal SCC patients with induction of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 35: e14635-e14635, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou W, Chen L. Inhibitory B7-family molecules in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol, 8: 467-477, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 12: 252-264, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz RH. Costimulation of T lymphocytes: the role of CD28, CTLA-4, and B7/BB1 in interleukin-2 production and immunotherapy. Cell, 71: 1065-1068, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med, 363: 711-723, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med, 8: 793-800, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med, 192: 1027-1034, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen K, Cheng G, Zhang F, et al. Prognostic significance of programmed death-1 and programmed death-ligand 1 expression in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget, 7: 30772-30780, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Y, Lo AWI, Wong A, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and PD-L1 expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget, 8: 30175-30189, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med, 372: 320-330, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med, 375: 1823-1833, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drake CG, Lipson EJ, Brahmer JR. Breathing new life into immunotherapy: review of melanoma, lung and kidney cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 11: 24-37, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science, 348: 69-74, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med, 13: 1050-1059, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki Y, Mimura K, Yoshimoto Y, et al. Immunogenic tumor cell death induced by chemoradiotherapy in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res, 72: 3967-3976, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mole RH. Whole body irradiation;radiobiology or medicine ? Br J Radiol, 26: 234-241, 1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kingsley DP. An interesting case of possible abscopal effect in malignant melanoma. Br J Radiol, 48: 863-866, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wersall PJ, Blomgren H, Pisa P, Lax I, Kalkner KM, Svedman C. Regression of non-irradiated metastases after extracranial stereotactic radiotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol, 45: 493-497, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demaria S, Ng B, Devitt ML, et al. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 58: 862-870, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mimura K, Shiraishi K, Kobayashi M, Kono T, Kono K. [The Mechanism of HLA Class I and PD-L1 Expression of Cancer Cells in Tumor Microenvironment]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho, 43: 1027-1029, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teng MW, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Smyth MJ. Classifying Cancers Based on T-cell Infiltration and PD-L1. Cancer research, 75: 2139-2145, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Igney FH, Krammer PH. Death and anti-death: tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nat Rev Cancer, 2: 277-288, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson CB. Apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of disease. Science, 267: 1456-1462, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li B, VanRoey M, Wang C, Chen TH, Korman A, Jooss K. Anti-programmed death-1 synergizes with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor—secreting tumor cell immunotherapy providing therapeutic benefit to mice with established tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 15: 1623-1634, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Elsas A, Hurwitz AA, Allison JP. Combination immunotherapy of B16 melanoma using anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing vaccines induces rejection of subcutaneous and metastatic tumors accompanied by autoimmune depigmentation. J Exp Med, 190: 355-366, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med, 369: 122-133, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mimura K, Kono K. [Therapeutic Cancer Vaccine and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho, 44: 733-736, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]