Abstract

Encoded by EEF1A1, the eukaryotic translation elongation factor eEF1α1 strongly promotes the heat shock response, which protects cancer cells from proteotoxic stress, following for instance oxidative stress, hypoxia or aneuploidy. Unexpectedly, therefore, we find that EEF1A1 mRNA levels are reduced in virtually all breast cancers, in particular in ductal carcinomas. Univariate and multivariate analyses indicate that EEF1A1 mRNA underexpression independently predicts poor patient prognosis for estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) cancers. EEF1A1 mRNA levels are lowest in the most invasive, lymph node-positive, advanced stage and postmenopausal tumors. In sharp contrast, immunohistochemistry on 100 ductal breast carcinomas revealed that at the protein level eEF1α1 is ubiquitously overexpressed, especially in ER+ , progesterone receptor-positive and lymph node-negative tumors. Explaining this paradox, we find that EEF1A1 mRNA levels in breast carcinomas are low due to EEF1A1 allelic copy number loss, found in 27% of tumors, and cell cycle-specific expression, because mRNA levels are high in G1 and low in proliferating cells. This also links estrogen-induced cell proliferation to clinical observations. In contrast, high eEF1α1 protein levels protect tumor cells from stress-induced cell death. These observations suggest that, by obviating EEF1A1 transcription, cancer cells can rapidly induce the heat shock response following proteotoxic stress, and survive.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women. With 1.7 million new cases diagnosed per year, it accounts for about 25% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide1. However, only a few prognostic and predictive biomarkers are routinely used for the selection of patients benefitting from specific therapies2. Examples include the estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) for endocrine therapies and human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) for targeted therapy3,4. However, clinical outcomes remain variable2. Therefore, new prognostic and predictive breast cancer biomarkers are required for more accurate prognoses and therapeutic decision making.

Chromosome instability (CIN) is a hallmark of cancer and refers to an increased rate of chromosomal abnormalities. Aberrant chromosomal rearrangements, including aneuploidy, partial chromosome gains or losses and translocations, often promote tumorigenesis. They do so by generating fusion genes or gene copy number alterations, which induce unbalanced expression of oncogenic proteins or tumor suppressors5–7. Global chromosomal imbalances, such as tetraploidy, may also promote subclonal heterogeneity, and this is strongly associated with poor patient prognosis and drug-resistance8,9. Thus, CIN signatures are developed and extensively used as clinical biomarkers10–12.

Widespread copy number changes as a result of CIN cause genetic and proteomic imbalances. Work from the Amon laboratory in particular showed that this disrupts proteome homeostasis, affecting protein degradation and folding, and causes proteotoxic stress13–15. A so-called ‘heat shock response’ (HSR) is elicited to counteract this cellular stress16,17. The HSR is an evolutionarily conserved protective mechanism for cells under intrinsic or environmental stress. It maintains proteome homeostasis by dramatically increasing the production of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in a short period of time to prevent protein misfolding, aggregation, aberrant trafficking and degradation. Recent studies have reported enhanced HSP expression in a broad range of human cancers18,19. HSPs can either stabilize oncogenic proteins, such as mutant TP5318, or suppress cell death, thus promoting tumor development20. HSP expression is regulated by transcription factors named heat shock factors (HSFs), which bind to Heat Shock Elements (HSEs) in promoters via the conserved HSF DNA-binding domain21. Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1) is the well-established master regulator of HSP expression in mammalian cells and has been shown to support oncogenesis22.

Two homologs of the eukaryotic translation elongation factor eEF1α exist: eEF1α1 and eEF1α2. They have well-defined roles in recruiting aminoacyl-tRNAs to the A site of ribosomes during protein synthesis, but only eEF1α1 is ubiquitously expressed. Besides this canonical function, eEF1α1 participates in signal transduction, cell proliferation, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis and the HSR. EEF1α1 overexpression has been observed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and knock-down reduces HCC cell proliferation and blocks cell cycle progression23,24. However, the clinical significance of eEF1α1 in breast cancer has not yet been established.

Here, we study EEF1A1 mRNA and eEF1α1 protein expression in breast cancer and investigate associations between misexpression and clinical parameters. We find that at the mRNA level, EEF1A1 is underexpressed and this is an independent marker for poor patient prognosis in ER+ breast cancer. Reduced mRNA expression is caused by EEF1A1 copy number loss and cell cycle-associated expression. Strikingly, however, at the protein level eEF1α1 is overexpressed in breast cancer tissues and this protects breast cancer cells from cell death under stress conditions.

Results

EEF1A1 mRNA is underexpressed in breast cancers

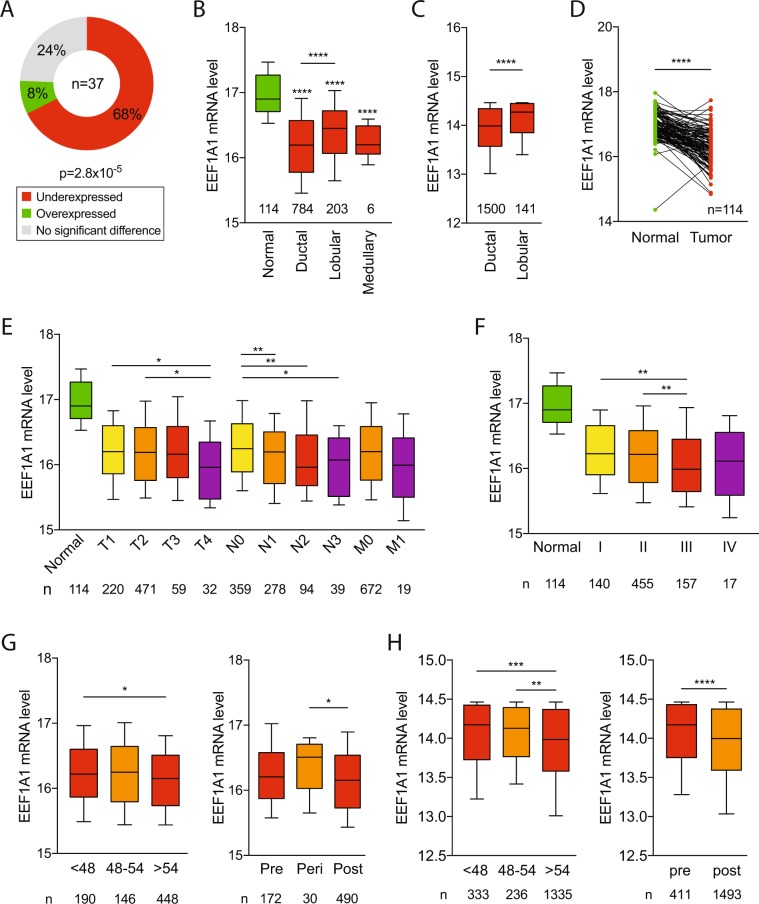

Using 37 analyses from 11 previously reported microarray datasets (Supplementary Table S1), we studied EEF1A1 mRNA expression levels in a broad range of breast cancers, including ductal, lobular, medullary and mucinous breast cancers25. Twenty-five out of 37 (68%) showed underexpressed EEF1A1 mRNA levels in breast cancers compared to normal breast tissue. Only 3 datasets (8%) showed overexpressed EEF1A1 mRNA levels in breast cancers (p = 2.8 × 10−5, Chi-square test; Fig. 1A). Notably, one of these three reports studied benign neoplasms and another involved phyllodes tumors, which may be benign or malignant, indicating that EEF1A1 mRNA is typically underexpressed in malignant breast cancer.

Figure 1.

EEF1A1 mRNA is underexpressed in breast cancer. (A) EEF1A1 mRNA levels in normal breast and breast cancer were pairwise compared in 37 microarray studies. The graph shows the distribution of studies reporting underexpression or overexpression in tumors or significant differential expression, as indicated. P-value: Chi-square test. (B) Box plot of normalized EEF1A1 mRNA expression in indicated breast carcinomas compared to normal breast tissue using the TCGA breast cancer RNAseq dataset. Whiskers show 10–90 percentiles. P-values: Mann-Whitney U tests. (C) Box plot of normalized EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast ductal carcinoma compared to lobular carcinoma using the METABRIC dataset. Whiskers show 10–90 percentiles. P-values: Mann-Whitney U test. (D) Normalized EEF1A1 mRNA expression in matched breast carcinoma and normal breast tissue pairs using the TCGA RNAseq dataset. P-value: Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. (E) Box plot of normalized EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast tumors for TNM stages, which includes tumor invasion (T1-T4), nodal status (N0-N3) and metastatic states (M0-M1), as indicated. Whiskers show 10–90 percentiles. P-values: Mann-Whitney U tests. (F) Box plot showing normalized EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast carcinomas for indicated tumor stages. Whiskers show 10–90 percentiles. P-values: Mann-Whitney U tests. (G) Box plot showing normalized EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast tumors for age and menopausal status using the TCGA RNAseq dataset. Whiskers show 10–90 percentiles. P-values: Mann-Whitney U tests. (H) Box plot showing normalized EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast tumors for age and menopausal status using the METABRIC dataset. Whiskers show 10–90 percentiles. P-values: Mann-Whitney U test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Using data from The Cancer Genomic Atlas (TCGA), we also assessed EEF1A1 mRNA expression levels from an RNAseq platform26. We compared 1097 breast tumors to 114 normal breast tissues. Similar to our previous observations, this showed that breast carcinomas – irrespective of their subtype – have significantly decreased mRNA expression compared to normal breast tissue (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 1B). Also, comparison between breast tumor histological subtypes showed that EEF1A1 expression is significantly lower in ductal breast carcinoma than in lobular breast carcinoma (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 1B). This observation was also confirmed in an independent dataset from METABRIC (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1C)27,28. In addition, paired analysis demonstrated that EEF1A1 levels are significantly lower in breast tumors compared to their matched normal breast tissues (p < 0.0001; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, Fig. 1D). Thus, together these observations indicate that at the mRNA level, EEF1A1 is underexpressed in virtually all breast cancers, but the degree of underexpression is subtype-dependent.

We next evaluated whether EEF1A1 mRNA expression might correlate with specific clinical parameters, including tumor invasion, nodal status, metastasis, stage, age and estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2 receptor status. There were no significant associations between EEF1A1 mRNA level and ER, PR or HER2 status (p > 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test; Supplementary Fig. S1). However, highly invasive T4 tumors, which invade into other organs, express lower EEF1A1 levels than T1 or T2 tumors, which only invaded into submucosa or muscle, respectively (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 1E). Additionally, N1/N2/N3 tumors, for which cancer cells have been detected in at least one axillary and/or other nearby lymph node, showed significantly lower EEF1A1 mRNA expression compared to N0 tumors from lymph node-negative patients (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 1E). Similarly, metastatic breast cancers showed lower EEF1A1 expression than non-metastatic tumors. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.209), possibly due to low statistical power (n = 19 metastatic tumors; Fig. 1E). We also observed decreased EEF1A1 levels in stage III tumors compared to stage I and stage II breast tumors (p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 1F). Finally, EEF1A1 levels are reduced in patients over age 54 or post-menopause (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 1G), a phenomenon that was confirmed in an independent patient cohort (Fig. 1H). Thus, these observations indicate that EEF1A1 mRNA expression declines with tumor invasion, dissemination to lymph nodes, advanced stage and post-menopause.

Low EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast cancer predicts poor patient survival

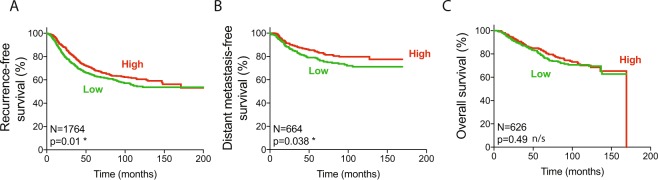

To decipher whether EEF1A1 mRNA expression can predict breast cancer patient prognosis, we first examined the recurrence-free survival (RFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) and overall survival (OS) from pooled datasets in the Kaplan-Meier plotter online tool using the median expression level as the cut-off between high and low EEF1A1 expressing tumors29. This showed that low EEF1A1 mRNA levels are associated with poor RFS and DMSF (p = 0.01 and p = 0.038, log-rank Mantel-Cox test; Fig. 2A,B) but not with OS (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, in the METABRIC dataset, which is about three times larger, we found that low EEF1A1 expression predicted poorer OS (p = 0.0123; Supplementary Fig. S2A).

Figure 2.

Low EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast cancer predicts poor patient survival. (A) Recurrence-free survival curve of patients from the Kaplan-Meier plotter dataset. Patients were split into high and low EEF1A1 mRNA expression groups using median expression level as the cut-off, determined as previously described29. (B) Distant metastasis-free survival curve. (C) Overall survival curve. P-values: log-rank Mantel-Cox tests. N/s, not significant; *p < 0.05.

Using the Kaplan-Meier plotter, we next assessed whether ER status affected the ability of EEF1A1 levels to predict RFS, DMSF and OS. This was not the case for ER+ or for ER- breast cancer patients (Supplementary Fig. S2B). However, somewhat consistent with the association between reduced EEF1A1 levels and increased invasion (Fig. 1E), only for DMFS of ER+ patients, low EEF1A1 levels showed a weak trend towards statistically significant association with poor survival (p = 0.14, n = 161). To explore this further, we studied a much larger combined cohort of 3874 patients, 2822 of whom were ER+ (Table 1)30. This indicated that low EEF1A1 mRNA levels correlate with poor DMFS in all breast cancers (p = 3.8 × 10−5, log-rank test; Table 1). However, this can entirely be attributed to patients with ER+ tumors (p = 5.7 × 10−7), as ER- patients showed no correlation (p = 0.9351; Table 1). Thus, low EEF1A1 levels predict poor breast cancer patient survival, in particular for patients with ER+ tumors.

Table 1.

Low EEF1A1 mRNA expression is an independent prognostic marker for ER+ breast cancer.

| Type | No. of patients | Survival | Univariate | Multivariatec | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMFSa | Prognostic strength | Adjuvant! Onlinec | Nottingham Indexc | |||||||

| P value | P value summary | HR (95% CI)b | P value | P value summary | P value | P value summary | P value | P value summary | ||

| All | 3874 | 3.8 × 10−5 | **** | 0.84 (0.79–0.90) | 2.5 × 10−7 | **** | 0.0262 | * | 0.0893 | n/s |

| ER+ | 2822 | 5.7 × 10−7 | **** | 0.78 (0.72–0.85) | 9.0 × 10−9 | **** | 0.0009 | *** | 0.0329 | * |

| ER− | 1022 | 0.9351 | n/s | 0.99 (0.88–1.12) | 0.8796 | n/s | 0.5355 | n/s | 0.6672 | n/s |

Low EEF1A1 mRNA expression is an independent marker for poor prognosis of ER+ breast cancer

It is well established that differential gene expression in breast cancer is often associated with key clinical parameters, such as tumor size and lymph node status. Therefore, it is critical to assess whether any potential marker retains prognostic strength independent of such variables using multivariate analyses. To test this, we first fitted a univariate Cox proportional hazard model on the combined 3874 patients from 26 independent datasets30 (Supplementary Table S1). This again indicated that EEF1A1 underexpression is a strong marker for poor prognosis for all breast cancers combined (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 0.84, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 0.79–0.90, p = 2.5 × 10−7; Table 1). However, this is solely due to patients with ER+ breast cancers (HR = 0.78, 95%CI = 0.72–0.85, p = 9.0 × 10−9; Table 1), as there is no univariate prognostic strength for ER- breast cancer patients (HR = 0.99, 95%CI = 0.88–1.12, p = 0.8796; Table 1).

To test whether EEF1A1 expression can independently predict patient prognosis, we applied multivariate analyses using clinical parameters included in Adjuvant! Online and the Nottingham Prognostic Index31,32. Adjuvant! Online is a computer program, which accounts for clinical parameters to estimate the risk of poor patient outcome in adjuvant therapy. The Nottingham Prognostic Index takes tumor size, grade and nodal status into account for post-surgery outcome prediction. Using the same combined datasets, following adjustment to these well-established concepts, we stringently determined in multivariate analyses that EEF1A1 mRNA underexpression is an independent prognostic biomarker for ER+ (p = 9.0 × 10−9 and p = 0.0329) but not ER- breast cancers (p = 0.8796, p = 0.6672; Table 1).

Low EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast carcinoma is not due to EEF1A1 mutations or hypermethylation of its promoter

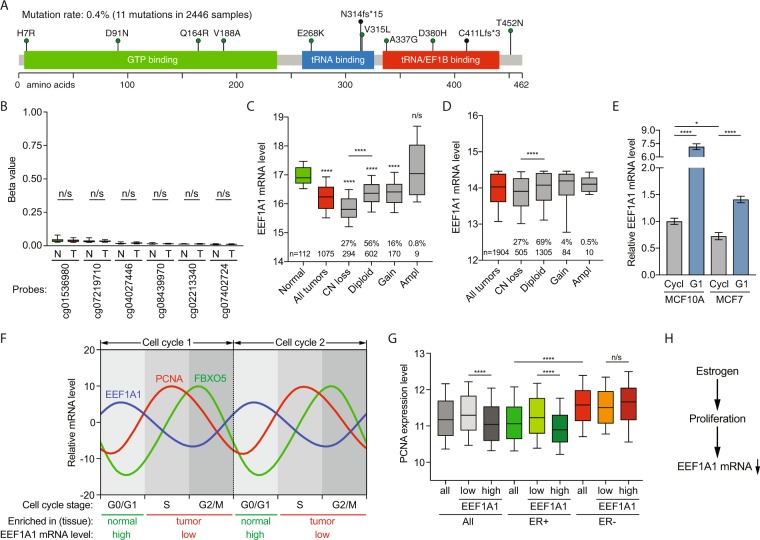

Next, we assessed whether mutations in EEF1A1 could account for the reduced EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast cancers. However, in a combination of multiple breast cancer datasets (see Methods and Supplementary Table S1), only 11 mutations were identified in 2,446 tumor samples (Fig. 3A). This low mutation rate of 0.4% could not explain the broad underexpression of EEF1A1 observed in breast cancer.

Figure 3.

Low EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast carcinoma is due to EEF1A1 allelic copy number loss and cell cycle-associated expression. (A) Mutations identified in 2,446 breast cancer samples from the COSMIC database (version 83, see Methods). The image was generated as described56,57 and modified. Scale bar indicates amino acid numbers. (B) Box plot of β-values of the six CpG probes in the EEF1A1 promoter 1000 base pairs upstream of the EEF1A1 transcription start site in normal breast tissue (N) and breast tumor (T). Data are derived from TCGA. P-values: Mann-Whitney U test; n/s, not significant. (C) Box plot of EEF1A1 mRNA expression level in breast carcinomas and normal breast tissue for indicated EEF1A1 allelic copy number status. Data are derived from the TCGA RNAseq and SNP6 microarray datasets26. P-values: Mann-Whitney U test. (D) Box plot as in (B) but using data from the METABRIC datasets27,28. P-values: Mann-Whitney U test. N/s, not significant; ****p < 0.0001. (E) Bar graph of EEF1A1 mRNA expression levels in asynchronously growing/cycling and serum-starved/G1-arrested MCF10A and MCF7 cells, as determined by qRT-PCR. Data are normalized to cycling MCF10A cells. P-values: Student t-test. *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001. (F) Graph showing oscillating, cell cycle stage-dependent mRNA expression levels of EEF1A1, the S-phase marker PCNA and the G2/M marker FBXO536. (G) Box plot of PCNA expression levels in breast carcinomas with indicated estrogen receptor (ER) status. Tumors were split into high and low EEF1A1 mRNA expression groups using median expression level as the cut-off. Data are derived from TCGA. P-values: Mann-Whitney U test. N/s, not significant; ****p < 0.0001. (H) Model for the relationship between estrogen receptor signaling and EEF1A1 mRNA expression in ER+ breast cancers.

To test whether EEF1A1 promoter methylation could explain the low mRNA expression, we compared the EEF1A1 promoter methylation level between normal breast tissue and breast carcinoma using the TCGA dataset26. However, we find that the CpG methylation status measured for all CpG probes that were located in the 1000 base pairs upstream of the EEF1A1 transcription start site were very low in both normal breast tissue and breast carcinoma tissue and these minimal differences did not significantly change (Fig. 3B), indicating that low EEF1A1 mRNA expression is not caused by hypermethylation of the EEF1A1 promoter.

Low EEF1A1 mRNA expression is due to EEF1A1 allelic copy number loss and cell cycle-associated expression

To test if EEF1A1 allelic copy number loss could contribute to low mRNA expression, we used the TCGA RNAseq dataset for mRNA expression and the SNP6 microarray dataset for somatic copy number aberrations26,33. EEF1A1 allelic copy number loss occurs in 27% of breast tumors, and this is significantly associated with reduced EEF1A1 mRNA expression compared to EEF1A1 diploid tumors (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 3C). Similarly, in the METABRIC dataset, 27% of breast cancers showed EEF1A1 copy number loss and these tumors also expressed significantly lower EEF1A1 than tumors diploid for EEF1A1 (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3D). However, EEF1A1 mRNA expression is also significantly lower in diploid tumors than in normal tissue (p < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 3C). Thus, EEF1A1 allelic copy number loss only partly accounts for the observed EEF1A1 mRNA underexpression.

Compared to normal cells, tumor cells are highly proliferative. Hence, relative to normal tissues, tumor tissues contain higher fractions of cells in S/G2/M stages of the cell cycle34,35. As this could potentially explain why EEF1A1 mRNA levels are reduced in breast carcinoma, we thus asked whether EEF1A1 mRNA expression is cell cycle-associated. To this end, we synchronized the breast cancer cell lines MCF10A and MCF7 in G1 stage of the cell cycle using serum-free media. Real-time quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that EEF1A1 mRNA levels are significantly upregulated in these G1-synchronized cells compared to respective asynchronously growing MCF10A and MCF7 cells (each p < 0.0001, unpaired t-test; Fig. 3E). In addition, the EEF1A1 mRNA level in more proliferative MCF7 cells is lower than in non-cancerous and less proliferative MCF10A cells (p < 0.05, unpaired t-test; Fig. 3E). This indicates that EEF1A1 mRNA levels are higher in cells in G1 stage than in cycling/proliferating cells.

Consistently, an independent approach36 shows that the relative EEF1A1 mRNA levels are 5.4, −1.2 and −5.7 during G1, S and G2/M stages of the cell cycle, respectively. This further confirms that EEF1A1 mRNAs oscillate during cell cycle progression, with these being the highest at G1 stage (Fig. 3F). Since, compared to normal tissues, tumor tissues are enriched for cells in S/G2/M stage of the cell cycle (Fig. 3F), these data strongly suggest that the G1-specific peak levels of EEF1A1 mRNA predominantly account for our observation that EEF1A1 mRNA levels are reduced in breast carcinoma.

Our above observations prompted us to also further explore a potential link between EEF1A1 mRNA levels and ER signaling. It is well-established that estrogen stimulates breast cancer cell proliferation37,38. Consistently, in ER+ tumors ER activity is higher in EEF1A1-low than in EEF1A1-high tumors, but in ER- tumors there is no significant difference (Supplementary Fig. S4). Further in line with this, while ER- tumors are more proliferative than ER+ tumors, as measured by the expression levels of the S phase-specific proliferation marker PCNA (Fig. 3F,G), EEF1A1 mRNA-low tumors are more proliferative than EEF1A1 mRNA-high tumors in ER+ but not in ER- breast cancers (Fig. 3G). Strikingly, these data closely resemble our earlier observation that low EEF1A1 mRNA levels are an independent marker for poor patient survival for ER+ but not for ER− breast cancer patients (Table 1). These results further suggest that EEF1A1 mRNA levels are reduced in ER+ breast tumors due to ER-induced cell proliferation (Fig. 3H).

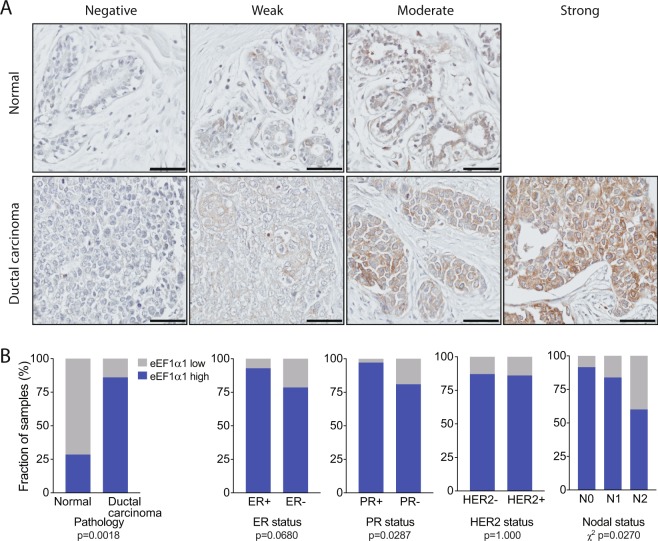

At the protein level, eEF1α1 is overexpressed in ductal breast carcinoma

We next asked whether EEF1A1 is also underexpressed in breast carcinomas at the protein level. To that end, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) on a tissue microarray, which included 7 adjacent normal breast tissues and 100 ductal breast carcinomas, using a previously well-characterized antibody39–41. Clinicopathological features and prognostic variables of the patients whose samples were analyzed are included in Supplementary Table S2.

Following an optimized IHC protocol (see Methods), we found that the staining intensities of the samples ranged from negative to moderate in normal breast tissues and from negative to strong in breast carcinomas (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, in sharp contrast to our observations at the mRNA level, at the protein level eEF1α1 seemed to be overexpressed in these ductal breast carcinomas compared to normal breast tissues. To stringently test this, we assigned H-scores to each sample using a multiplicative IHC quick-score method (see Methods). H-scores account for both the staining intensity and the fraction of positive cells, ranging from 0 (negative) to 300 for all epithelial cells showing strong staining. First, using an H-score of 50 as a cut-off, we found that high eEF1α1 expression was significantly more common in ductal carcinoma (86 of 100, 86%) than in normal breast tissue (2 of 7, 29%; p = 0.0018, Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 4B, Table 2).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry shows that eEF1α1 protein is overexpressed in ductal breast carcinoma. (A) A tissue microarray with a total of 7 adjacent normal breast tissues and 100 ductal breast carcinomas was immunohistochemically stained with an anti-eEF1α1 antibody. Representative images of various staining intensities are shown. Scale bars: 50 μm. (B) Distributions of high and low eEF1α1-expressing tissue samples, using an immunohistochemistry-derived H-score of 50 as a cutoff. Data are analyzed for several clinical parameters, as indicated. P-values: Fisher’s exact tests or Chi-square tests, as indicated.

Table 2.

EEF1α 1 expression in normal breast and ductal breast carcinoma tissues.

| Variable | Number of samples with H-score >50/total (%) | p value vs normala,b | Other (p value)a,b |

|---|---|---|---|

| All samples | |||

| Normal breast | 2/7 (29) | ||

| Ductal carcinoma | 86/100 (86) | 0.0018 | |

| Grade | |||

| 2 | 46/54 (85) | 0.0035 | |

| 3 | 36/42 (86) | 0.004 | |

| Tumor invasion | |||

| T1 | 8/10 (80) | 0.0584 | |

| T2 | 55/62 (89) | 0.0012 | |

| T3 | 14/16 (88) | 0.0107 | |

| T4 | 9/12 (75) | 0.0739 | |

| Nodal status | |||

| N0 | 54/59 (92) | 0.0005 | N0 vs N2 (0.0207) |

| N1 | 26/31 (84) | 0.008 | N0/N1 vs N2 (0.0316) |

| N2 | 6/10 (60) | 0.3348 | |

| Metastasis | |||

| M0 | 86/99 (88) | 0.0014 | |

| M1 | 0/1 (0) | 1.000 | |

| Estrogen Receptor status | |||

| ER+ | 52/56 (93) | 0.0003 | ER+ vs ER− (0.068) |

| ER− | 33/42 (79) | 0.0151 | |

| Progesterone Receptor status | |||

| PR+ | 34/35 (97) | 0.0001 | PR+ vs PR− (0.0287) |

| PR− | 51/63 (81) | 0.077 | |

| HER2 receptor status | |||

| HER2+ | 31/36 (86) | 0.0043 | HER2+ vs HER2− (1.0) |

| HER2− | 54/62 (87) | 0.0019 | |

| Age/Menopausal status | |||

| <48 | 46/56 (82) | 0.0066 | |

| 48–54 | 23/25 (92) | 0.0019 | |

| >54 | 17/19 (89) | 0.0057 | |

aCalculated using Fisher’s exact test.

bP values in bold remain statistically significant at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05.

Second, we assessed whether EEF1A1 protein expression specifically associated with several clinical parameters. High eEF1α1 expression occurred in more ER+ than ER- tumors (93% versus 79%) and this difference approached statistical significance (p = 0.0680; Fig. 4B). Significantly more PR+ tumors expressed high eEF1α1 (97% versus 81%, p = 0.0287; Fig. 4B). However, we did not observe any significance between HER2+ and HER2− tumors (86% versus 87%, p = 1; Fig. 4B). In addition, eEF1α1 expression in N0 tumors is significantly higher than in N1/N2 tumors (p = 0.0207, Chi-square test; Fig. 4B), but there are no significant differences based on age (p = 0.4427), metastatic state (p = 0.1400), tumor invasion (p = 0.5907) or tumor grade (p = 1.0; Supplementary Fig. S3A).

Finally, despite the fact that there is no significant association between thresholded H-scores and age groups, as a continuous variable the H-score of eEF1α1 expression is significantly increased in patients over age 54 (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test; Supplementary Fig. S3B). Taken together, at the protein level, eEF1α1 is significantly overexpressed in PR+ and lymph node-negative ductal breast carcinomas, as well as in tumors of patients over 54 years of age.

EEF1α1 protein expression levels parallel cellular stress levels

To investigate the role of elevated eEF1α1 protein expression in breast cancer, we first performed Western blot analysis on breast cancer cell lines. We found that eEF1α1 expression is higher in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells than in non-cancerous MCF10A cells (Fig. 5A,B, Supplementary Fig. S5). Consistently, mass spectrometric determination of protein levels in these cell lines42 also independently showed significantly higher eEF1α1 protein levels in MDA-MB-231 cells compared to MCF10A cells (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

EEF1α1 protein expression levels parallel cellular stress levels. (A) Western blots showing eEF1α1 and β-actin protein levels in MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines. (B) Quantification of β-actin-normalized eEF1α1 protein levels in MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cell lines using the Western blots shown in (A). (C) Bar graph of normalized eEF1α1 protein levels in MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cell lines using mass spectrometric quantification (each n = 2)42. (D) Protein expression levels of the heat shock response-inducible HSP90 isoforms α1 and α2. (E) Model explaining the contradictory EEF1A1 mRNA and eEF1α1 protein misexpression in breast carcinoma.

A recent study showed that eEF1α1 strongly promotes the heat shock response43, which is induced following proteotoxic stress, caused by for instance thermal shock, oxidative stress or aneuploidy. In line with this, compared to non-tumorigenic MCF10A cells, increased eEF1α1 protein levels in cancerous MDA-MB-231 cells are paralleled by increased protein expression of both the α1 and α2 isoforms of the stress-induced heat shock protein HSP90 (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

Chromosome instability (CIN) may occur via a range of mechanisms, including cell cycle checkpoint defects, aberrant DNA repair, failed DNA replication and mitotic dysregulation, and CIN is common in solid cancers due to p53 or RB pathway defects5,7,8,44,45. Copy number alterations in particular result in dramatically imbalanced proteome homeostasis and heterogeneity within the tumor and this is associated with poor patient outcome and multi-drug resistance13–15. CIN impairs protein folding, induces proteotoxic stress and may trigger the heat shock response (HSR)13–15,46,47. Our interest in CIN and its consequences led us to study eEF1α1, which was recently shown to strongly promote the HSR43.

We find that EEF1A1 mRNA is underexpressed in advanced breast cancers. Consistently, our qRT-PCR analyses show lower EEF1A1 mRNA levels in the breast cancer cell line MCF7 than in non-cancerous MCF10A cells. Underexpression occurs in particular in invasive, lymph node-positive, advanced stage and postmenopausal tumors, suggesting that EEF1A1 mRNA levels typically decline as breast cancers become more malignant. Using stringent multivariate analyses, which account for various other clinical variables, we also demonstrate that low EEF1A1 mRNA is an independent prognostic marker for ER+ but not for ER− breast cancer patients.

We studied four potential mechanisms that could explain reduced EEF1A1 mRNA expression in breast cancer. We essentially ruled out EEF1A1 mutations and promoter hypermethylation, as they are very rare or non-existent. However, EEF1A1 allelic copy number loss occurs in 27% of tumors and this significantly reduced EEF1A1 mRNA levels compared to diploid tumors. Yet, as diploid tumors also showed significantly lower EEF1A1 expression levels than normal breast tissues, this can only partly explain the widespread EEF1A1 mRNA underexpression. Indeed, we believe that cell cycle-associated oscillation of EEF1A1 mRNA levels, which peak in G1 phase, is a major cause. Our cell synchronization experiments and microarray data both show significantly decreased EEF1A1 mRNA levels in proliferating cells. Tumors are proliferative and therefore enriched in cells in S/G2/M phases of the cell cycle compared to normal tissues with most cells in G0/G1 phase34,35. Thus, G1 phase-specific EEF1A1 mRNA expression seems the major cause of underexpression in breast cancers (Fig. 5E).

Interestingly, this finding also provides an explanation for why EEF1A1 mRNA underexpression is prognostic for ER+ tumors only. Consistent with the above, ER+ tumors with low EEF1A1 mRNA expression show higher expression of the proliferation marker PCNA compared to ER+ tumors with high EEF1A1 mRNA expression. However, this difference is not observed for ER- breast cancers. Since estrogen has been shown to promote breast cancer proliferation37,38, this suggests a direct relationship between estrogen signaling and EEF1A1 mRNA expression (Fig. 3H).

In sharp contrast to reduced EEF1A1 mRNA expression, we observed that at the protein level, eEF1α1 is overexpressed in breast carcinomas, in particular in ER+, PR+ and lymph node-negative tumors. This is consistent with observations in hepatocellular carcinomas48,49. We also find that in breast cancer cell lines, eEF1α1 levels correlate with protein levels of HSP90α1 and HSP90α2, which are markers of the heat shock response (HSR). This is in line with other recent findings, including that eEF1α1 strongly promotes the HSR43,50. Importantly in fact, reduction of high eEF1α1 protein levels by short hairpin RNAs was shown to, under stress conditions, protect MDA-MB-231 cells from cell death43, thus providing a malignant advantage to breast cancer cells. Collectively, this indicates that eEF1α1 protects breast cancer cells from stress-induced cell death by promoting the HSR. It may do so by recruiting HSF1, the master regulation of the HSR, to critical promoters43, which may subsequently stabilize oncoproteins, such as mutant p5318.

The discrepancy between the direction of EEF1A1 mRNA and protein misexpression (Fig. 5E) suggests strong post-transcriptional regulation. For this, mRNA regulatory elements and the affinity of RNA Binding Proteins (RBPs) could be important. Both post-transcriptional mechanisms have been linked to enhanced mRNA stability and translational efficiency of mRNA molecules, leading to abnormal protein overexpression in tumor cells51. Alternatively, post-translational modifications of eEF1α1 could markedly stabilize eEF1α1 proteins and prevent their degradation.

Taken together, we observe contradictory mRNA and protein misexpression of EEF1A1 in ductal breast carcinoma. However, both are significantly associated poor patient outcome. Cell cycle-associated EEF1A1 mRNA expression and the HSR, protecting tumor cells from stress-induced cell death, explain the opposite direction of misexpression and indicates strong post-translational control of eEF1α1 protein levels in tumors.

Methods

Gene expression analyses

EEF1A1 mRNA expression levels were evaluated in a range of previously published datasets (Supplementary Table S1)25. For in-depth analyses, EEF1A1 mRNA expression values from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Illumina HiSeq2000 RNA sequencing breast cancer dataset were used (Supplementary Table S1)26,33. Level 3 log2-normalized EEF1A1 mRNA expression levels were used for comparisons between normal and tumor samples and/or between samples of different breast cancer subtypes, age, menopause status, stages, hormone receptor status (ER, PR, and HER2), tumor invasion, lymph node status, and metastatic state. Similar comparisons were performed using the METABRIC dataset27,28. In the analyses, normal tissues refer to healthy tissues from cancer patients. Matched statistical analyses were performed as described52. As indicated, Mann-Whitney U tests or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests were used to assess whether the differences were statistically significant.

Somatic mutation analysis

Breast cancer-specific EEF1A1 somatic mutations were identified using 2,446 samples from the COSMIC database (version 83; Supplementary Table S1)53. Most of these samples were from the TCGA whole exome sequencing (n = 982), International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) (n = 569) and INSERM (n = 213) breast cancer datasets33,54,55. Mutation data were visualized as described56,57 but with minor modifications, as indicated.

DNA methylation analysis

EEF1A1 promoter methylation levels were determined from Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 platform level 3 TCGA data26, as described58, using the β-values for all CpG probes in the region between positions −1000 and +1 base pairs with respect to the EEF1A1 transcription start site.

Somatic copy number alteration analyses

EEF1A1 allelic somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) were analyzed and processed as previously described58. Briefly, Affymetrix Genome-Wide SNP6.0 Array data were obtained from the TCGA breast cancer studies26,33. These were processed using GISTIC2.0 and allelic copy number status (loss, diploid, gain or amplification) was determined for each sample.

Survival analyses

Survival analyses were performed either using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter tool29 or using Illumina HT-12v3 microarray gene expression data from the METABRIC study27,28. Patients were grouped into low and high expression, using the median expression as the cut-off, as described30. Survival curves were re-plotted in GraphPad Prism. For all comparisons of survival curves, log-rank Mantel-Cox tests were used to assess statistical significance.

Clinical prognostic analyses

The strength of EEF1A1 expression as a prognostic marker, in all breast cancers and in ER+ and ER− tumors separately, was determined using univariate an multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses, as described11. Briefly, reported univariate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) only assessed EEF1A1 expression. For multivariate analyses, clinical parameters included in Adjuvant Online!31 and the Nottingham Prognostic Index32 were included as co-variates to determine the respective HRs with 95% CIs.

Tissue samples, ethics statement and immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples on the tissue microarray (TMA) slides were obtained under Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-approved protocols, in accordance with the approved guidelines and with informed consent from the donors. With ethical approval from the Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC) at the University of Queensland, immunohistochemistry was performed as described12, with modifications. Breast cancer TMA slides (US Biomax) were baked at 60 °C for 30 minutes, de-paraffinized with xylene at room temperature (RT) for 3 min, 2 min and 2 min each and rehydrated by ethanol series 100%, 90%, 70%, each twice for 2 min and once for 2 min in ddH2O. Antigen retrieval was followed by incubating slides with sodium citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween-20, pH6) at 85 °C for 20 min in a pressure cooker. Slides were cooled at RT for 20 min, washed with TBS three times and incubated with 0.3% H2O2 in TBS for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After three TBS washes, slides were incubated with blocking buffer (MACH 1™, Biocare Medical) for 10 min, with rabbit anti-human eEF1α1 primary antibody (Proteintech, #11402-1-AP) in 1:800 dilution for 2 hours at RT, washed with TBS three times and incubated with secondary antibody (HRP-polymer, MACH 1™, Biocare Medical) for 30 min at RT. Next, slides were washed with TBS three times, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) was applied as the chromogen and hematoxylin was used to counterstain nuclei. Tissues on slides were dehydrated in backwards ethanol series (70%, 90%, 100%) for 2 min each and slides were heated to 60 °C to dry. Finally, slides were incubated with xylene for 2 min and coverslips and Permount mounting medium (Fisher Scientific) were applied.

Images were acquired using Virtual Slide Microscope (VS120, Olympus). Slides were independently scored by two individuals and in a blinded fashion. A multiplicative IHC quick-score method was applied as follows. The average intensity of the staining (on a scale of 0 to 3) was multiplied by the proportion of positively stained epithelial/tumor cells in the section (on a scale of 0 to 100%)59. Clinical endpoints examined are included in Table 2. H-scores of ≤50 and >50 were considered low and high in eEF1α1 expression, respectively. Fisher’s exact and Chi-square tests were used to assess whether differences were statistically significant.

Cell culture and synchronization

MCF10A cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) with 5% horse serum, 20 ng/ml rhEGF, 500 ng/ml hydrocortisone, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, 0.01 mg/ml insulin and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (p/s). MCF7 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.01 mg/ml insulin, 1% L-glutamine +1% sodium pyruvate and 1% p/s. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in the same medium but without insulin. For G1 phase cell cycle synchronization, cells were cultured in serum-free media containing 1 mg/ml BSA for 24 hours.

Western blot analysis

Cells were grown in 25T-flasks and collected at 70–80% confluence. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0 and 1:400 dilution of Protease Inhibitors Cocktail (P8340, Sigma)). Proteins were separated in 8–20% Tris-Acetate gels at 100 V for 2 hr and wet-transferred onto the Immunobilin-FL PVDF membranes (0.45μm pore size, Merck Millipore) at 90 V and 4 °C for 2 hr using Mini Trans-Blot® Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-rad). Membranes were blocked with TBS-based Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-COR) for 1 hr, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies rabbit anti-human eEF1α1 (Proteintech, #11402-1-AP; 1:1000 dilution) and mouse anti-human β-actin (SC-47778, Santa Cruz) at 4 °C. Membranes were washed four times with TBS-T (0.05% of Tween-20) for 5 min each, incubated with secondary antibodies (Li-COR, 680-red or 800-green) for 1 hr at RT and scanned and quantified on an Odyssey CLX imager (Li-COR). Normalized eEF1α1 protein levels were determined by dividing eEF1α1 levels by β-actin levels.

Real-time quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Reverse transcription was performed with Tetro cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bioline) according to manufacturer’s description. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR-green PCR master mix using QuantStudio™ 7 Flex Real-Time PCR Instrument (both Thermo Fisher Scientific) with cycling conditions recommended by the manufacturer. The EEF1A1 raw PCR cycles (CT) values were normalized (ΔCT) to internal control (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1; HPRT1) CT values. Relative mRNA level changes were determined by 2−ΔΔCT calculation using MCF10A asynchronous cells as controls. Primers used were: HPRT1-forward: TCAGGCAGTATAATCCAAAGATGGT, reverse: AGTCTGGCTTATATCCAACACTTCG60; EEF1A1-forward: GGACACGTATCGGGCAA, reverse: AGGAGCCCTTTCCCATCTCA.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Cheng-Yu Lin is supported by an International Postgraduate Research Scholarship (IPRS) and a UQ Centennial Scholarship (UQCent). Pascal HG Duijf is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Breast Cancer Foundation. This work is also supported by funds from the University of Queensland Diamantina Institute.

Author Contributions

C.Y.L. performed experiments, acquired, analyzed and interpreted data, designed the study and drafted the manuscript; A.B. analyzed and interpreted data; B.B. interpreted data, edited the manuscript; E.D. interpreted data, co-supervised the study, edited the manuscript; P.H.G.D. analyzed and interpreted data, designed and supervised the study, edited the manuscript, acquired funding; all authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All datasets analyzed in the current study are available via the links and references included in Supplementary Table S1.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32272-x.

References

- 1.Ghoncheh M, Pournamdar Z, Salehiniya H. Incidence and Mortality and Epidemiology of Breast Cancer in the World. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:43–46. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.S3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weigel MT, Dowsett M. Current and emerging biomarkers in breast cancer: prognosis and prediction. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R245–262. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tremont A, Lu J, Cole JT. Endocrine Therapy for EarlyBreast Cancer: Updated Review. Ochsner J. 2017;17:405–411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gajria D, Chandarlapaty S. HER2-amplified breast cancer: mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance and novel targeted therapies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11:263–275. doi: 10.1586/era.10.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duijf PH, Benezra R. The cancer biology of whole-chromosome instability. Oncogene. 2013;32:4727–4736. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CY, et al. Translocation breakpoints preferentially occur in euchromatin and acrocentric chromosomes. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10:e13. doi: 10.3390/cancers10010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duijf PH, Schultz N, Benezra R. Cancer cells preferentially lose small chromosomes. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2316–2326. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka K, Hirota T. Chromosomal instability: A common feature and a therapeutic target of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1866:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habermann JK, et al. The gene expression signature of genomic instability in breast cancer is an independent predictor of clinical outcome. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1552–1564. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter SL, Eklund AC, Kohane IS, Harris LN, Szallasi Z. A signature of chromosomal instability inferred from gene expression profiles predicts clinical outcome in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1043–1048. doi: 10.1038/ng1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thangavelu PU, et al. Overexpression of the E2F target gene CENPI promotes chromosome instability and predicts poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:62167–62182. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaidyanathan S, et al. In vivo overexpression of Emi1 promotes chromosome instability and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2016;35:5446–5455. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oromendia AB, Dodgson SE, Amon A. Aneuploidy causes proteotoxic stress in yeast. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2696–2708. doi: 10.1101/gad.207407.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres EM, et al. Effects of aneuploidy on cellular physiology and cell division in haploid yeast. Science. 2007;317:916–924. doi: 10.1126/science.1142210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheltzer JM, Torres EM, Dunham MJ, Amon A. Transcriptional consequences of aneuploidy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12644–12649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209227109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt CR, et al. Genomic instability and enhanced radiosensitivity in Hsp70.1- and Hsp70.3-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:899–911. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.899-911.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oromendia AB, Amon A. Aneuploidy: implications for protein homeostasis and disease. Disease models & mechanisms. 2014;7:15–20. doi: 10.1242/dmm.013391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CS, et al. Overexpression of heat shock protein (hsp) 70 associated with abnormal p53 expression in cancer of the pancreas. Zentralbl Pathol. 1994;140:259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calderwood SK, Khaleque MA, Sawyer DB, Ciocca DR. Heat shock proteins in cancer: chaperones of tumorigenesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudeja V, et al. Heat shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis in cancer cells through simultaneous and independent mechanisms. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1772–1782. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akerfelt M, Trouillet D, Mezger V, Sistonen L. Heat shock factors at a crossroad between stress and development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:15–27. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai C, Whitesell L, Rogers AB, Lindquist S. Heat shock factor 1 is a powerful multifaceted modifier of carcinogenesis. Cell. 2007;130:1005–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, et al. The Ubiquitin-like Protein FAT10 Stabilizes eEF1A1 Expression to Promote Tumor Proliferation in a Complex Manner. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4897–4907. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farra R, et al. Dissecting the role of the elongation factor 1A isoforms in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by liposome-mediated delivery of siRNAs. Int J Pharm. 2017;525:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhodes DR, et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia. 2007;9:166–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis C, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira B, et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refines their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gyorffy B, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaidyanathan S, Thangavelu PU, Duijf PH. Overexpression of Ran GTPase components regulating nuclear export, but not mitotic spindle assembly, marks chromosome instability and poor prognosis in breast cancer. Target Oncol. 2016;11:677–686. doi: 10.1007/s11523-016-0432-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravdin PM, et al. Computer program to assist in making decisions about adjuvant therapy for women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:980–991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galea MH, Blamey RW, Elston CE, Ellis IO. The Nottingham Prognostic Index in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992;22:207–219. doi: 10.1007/BF01840834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ciriello G, et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of invasive lobular breast cancer. Cell. 2015;163:506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauer KD, et al. Prognostic implications of proliferative activity and DNA aneuploidy in colonic adenocarcinomas. Lab Invest. 1987;57:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barlogie B, et al. Flow cytometry in clinical cancer research. Cancer Res. 1983;43:3982–3997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kittler R, et al. Genome-scale RNAi profiling of cell division in human tissue culture cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1401–1412. doi: 10.1038/ncb1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fanelli MA, et al. Estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and cell proliferation in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;37:217–228. doi: 10.1007/BF01806503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ciocca DR, Fanelli MA. Estrogen receptors and cell proliferation in breast cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1997;8:313–321. doi: 10.1016/S1043-2760(97)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizuno, K. et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes in human cryptorchid testes using suppression subtractive hybridization. J Urol181, 1330-1337; discussion 1337, 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.034 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Bao H, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of a paired human liver healthy versus carcinoma cell lines with the same genetic background to identify potential hepatocellular carcinoma markers. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2009;3:705–719. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neuhaus N, et al. Single-cell gene expression analysis reveals diversity among human spermatogonia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2017;23:79–90. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaw079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawrence RT, et al. The Proteomic Landscape of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cell Rep. 2015;11:990. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vera M, et al. The translation elongation factor eEF1A1 couples transcription to translation during heat shock response. Elife. 2014;3:e03164. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Targa A, Rancati G. Cancer: a CINful evolution. Current opinion in cell biology. 2018;52:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schvartzman JM, Duijf PH, Sotillo R, Coker C, Benezra R. Mad2 Is a Critical Mediator of the Chromosome Instability Observed upon Rb and p53 Pathway Inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:701–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donnelly N, Storchova Z. Causes and consequences of protein folding stress in aneuploid cells. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:495–501. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1006043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donnelly N, Storchova Z. Aneuploidy and proteotoxic stress in cancer. Mol Cell Oncol. 2015;2:e976491. doi: 10.4161/23723556.2014.976491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen SL, et al. eEF1A1 Overexpression Enhances Tumor Progression and Indicates Poor Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2018;11:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang J, et al. Overexpression of eEF1A1 regulates G1-phase progression to promote HCC proliferation through the STAT1-cyclin D1 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;494:542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nigro A, et al. Recombinant Arabidopsis HSP70 Sustains Cell Survival and Metastatic Potential of Breast Cancer Cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1063–1073. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Audic Y, Hartley RS. Post-transcriptional regulation in cancer. Biol Cell. 2004;96:479–498. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shajari N, et al. Silencing of BACH1 inhibits invasion and migration of prostate cancer cells by altering metastasis-related gene expression. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46:1495–1504. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1374284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forbes SA, et al. COSMIC (the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer): a resource to investigate acquired mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D652–657. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lefebvre C, et al. Mutational Profile of Metastatic Breast Cancers: A Retrospective Analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nik-Zainal S, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2016;534:47–54. doi: 10.1038/nature17676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cerami E, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao J, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thangavelu PU, Krenacs T, Dray E, Duijf PH. In epithelial cancers, aberrant COL17A1 promoter methylation predicts its misexpression and increased invasion. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:120. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0290-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Detre S, Saclani Jotti G, Dowsett M. A “quickscore” method for immunohistochemical semiquantitation: validation for oestrogen receptor in breast carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:876–878. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.9.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gatica-Andrades M, et al. WNT ligands contribute to the immune response during septic shock and amplify endotoxemia-driven inflammation in mice. Blood Adv. 2017;1:1274–1286. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017006163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets analyzed in the current study are available via the links and references included in Supplementary Table S1.