Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common malignant primary tumor in the central nervous system. Despite advances in neurosurgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, the median survival time of GBM patients is only 9 to 16 months.1 Therefore, GBM is considered one of the deadliest human cancers. In the past two decades, many efforts have been made by scientists and clinicians to develop new drugs to improve current therapies. Unfortunately, most efforts have not achieved long-term remissions in clinical trials, even though some of them are promising in animal models, making treatment options still limited.2

During the past 10 years, great progress in cancer genomic studies have revealed genetic mutations that may serve as drivers in many types of cancers. Knowledge about those driver mutations greatly improves our understanding of cancer biology and leads to new diagnostic strategies and novel cancer therapies, such as targeting therapy. In melanoma, for example, compared to traditional chemotherapy, Vemurafenib, a BRAF kinase inhibitor, shows great advantages for patients possessing specific mutations in the BRAF gene.3 Like melanoma, the key genetic lesions involved in gliomagenesis have been reported. However, there has been very limited progress in GBM therapy. Therefore, new insights and ideas are urgently needed to reveal the developmental biology of malignant GBM. Here, we rethink GBM from its cellular origin and try to elucidate the implications for GBM precision therapy.

Cellular origin of GBM multiforme

It is believed that there are three cells of origin for GBM, neural stem cells (NSCs), NSC-derived astrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). This generally accepted view is based on observations such as the following: (1) Cell surface marker expression and cell morphology in GBM tissues are similar to those of normal cell types in the central nervous system (CNS). (2) The similarity of gene profiles between GBM and those normal cell types. (3) Genetic modeling of GBM in mice showing that many cell types in the CNS such as NSCs,4 NSC-derived astrocytes5 and OPCs are able to develop into GBMs.6 The cellular origin is a major determinant of the molecular subtype and may contribute to tumor development.7 Consistent with this concept, it was found that tumors derived from different cellular origins exhibited different behaviors in GBM mouse models. This observation suggests that the cellular origin could significantly contribute to GBM development and indicates the importance of better understanding regarding the nature and consequences of cellular origin in GBM.8

It is worth noting that cells acquiring initial mutations (cells of mutation) may not directly transform into the malignancy. This confusing concept makes identification of the cells of origin challenging. An alternative solution to tease apart the cellular origin and to identify the cells of mutation is to analyze individual cell lineages along the entire developmental process of tumorigenesis by using a genetically mosaic mouse model termed MADM (Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers).9,10 Via Cre/loxP-mediated mitotic interchromosomal recombination, MADM generates a small number of homozygous mutated cells labeled with green fluorescent protein (GFP), thus mimicking the sporadic loss of heterozygosity in tumor suppressor genes in human cancers.10 Moreover, MADM also labels sibling wild-type cells with red fluorescent protein, allowing the direct phenotypic comparison between the mutant and wild-type sibling cells at a single-cell resolution in vivo, with the latter as an ideal internal control. Meanwhile, the permanent labeling of mutant cells with GFP allows lineage tracing of these cells. By using MADM-based lineage tracing in the mouse model, it was convincingly demonstrated that rather than being derived from other types of NSC progenies, p53/NF1 mutation-induced GBM was derived from OPC and was clustered as the proneural subtype.6 However, the cellular origins of other GBM subtypes are still unclear and need further study.

How does the cell of origin influence drug development and precision therapy?

Cell culture-based assays are an important platform for drug discovery, providing a simple and fast tool for high-throughput screening.11 Cultured cells and culture conditions are the most important elements of such a technique. In GBM research, established cell lines have been gradually replaced by primary cell cultures for two reasons. First, acute primary cells are more representative of in vivo cancer cell phenotypes. Second, acute primary cells can maintain the heterogeneity of the original tumor, while established cell lines are more homogeneous because of the selective culture conditions.

GBM is one of the most aggressive and heterogeneous tumor types.12 The major challenge is to find proper growth conditions that minimize alterations in the biological status of cancer cells in vitro. Numerous studies have showed promising results that culture conditions can be optimized based on the cellular origin. For example, it was reported that GBM cells originating from mouse OPCs could maintain similar gene expression profiles and similar capacity for tumorigenesis compared to freshly isolated tumor cells when cultured in a medium suitable for normal OPCs. However, the same cells cultured in a medium suitable for NSCs would lose their OPC features and became much more sensitive to temozolomide. A similar phenomenon was also observed in primary cultured human GBM cells of the proneural subtype, which is like those of OPC origin.13 Sreedharan et al. 14 showed that NSC-originating tumor cells exhibited higher tumor incidence and malignancy when cultured under stem cell conditions compared to OPC conditions. Jiang et al. 15 divided patient-derived GBM cells into functionally distinct groups based on cellular origin. Most important, human primary GBM cells that clustered as having originated from NSCs were much more tumorigenic and more sensitive to cancer drugs compared to those clustered as having originated from OPCs.15 Taking together, these findings provide clear evidence that cellular origin should serve as the basis for future GBM classification and drug development. In addition, immunotherapy showed great progress and potential in treating GBM.16 Practically, studies should avoid choosing immune antigens expressed in both tumor cells and pretransformed cells to prevent dramatic side effects.

Perspective

Owing to the high heterogeneity of GBM, most promising drugs have failed in clinical trials. Identification of the cellular origins of GBM exhibits great significance for both medical and basic research. For clinicians, the cellular origin provides a pretransformation window for tumors, giving them an ideal therapeutic targeting cell. On the other side, cellular origin can also help basic researchers understand why the given mutations only induce transformation in restricted cell types within the body.

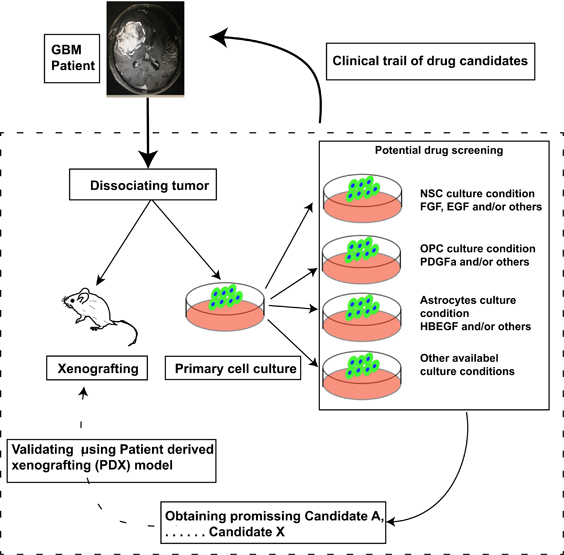

Using global profiling of gene expression, GBM was divided into proneural, neural, classical and mesenchymal subtypes, which might not be representative of entire individual tumors, but only of a subgroup of cells within individual tumors. Classification based on cellular origin is more informative and relevant for clinical applications. In precision therapy of GBM, a platform based on the cellular origin theory will provide a powerful new engine to drive therapeutic drug screening (Figure 1). In addition to GBM, this approach could also be applicable to other tumors. In addition to basic research, drug discovery studies could greatly benefit from this strategy, thus improving the process of developing more efficient drugs for cancer patients.

Figure 1.

Schematic of platform based on cellular origin. Dissociated tumor cells were divided into two populations. One half was injected into immunodeficient mice, and the other was cultured in several conditions. When doing drug screening, the candidate that shows great potential in either condition should be validated in a patient-derived xenografting (PDX) model in vivo. After validation in PDX, the remaining candidates should move to clinical trials in glioma patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSFC81302187, CWS14C063 and SIMM1705KF-10 (State Key Laboratory of Drug Research).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Hua He, Email: rj11118@163.com.

Liuguan Bian, Email: panda1979hh@sina.com.

References

- 1.Maher EA, Furnari FB, Bachoo RM, Rowitch DH, Louis DN, Cavenee WK, et al. Malignant glioma: genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1311–1333. doi: 10.1101/gad.891601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He H, Yao M, Zhang W, Tao B, Liu F, Li S, et al. MEK2 is a prognostic marker and potential chemo-sensitizing target for glioma patients undergoing temozolomide treatment. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:658–668. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, BRIM-3 Study Group et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Y, Guignard F, Zhao D, Liu L, Burns DK, Mason RP, et al. Early inactivation of p53 tumor suppressor gene cooperating with NF1 loss induces malignant astrocytoma. Cancer Cell. 2005;2:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow LM, Endersby R, Zhu X, Rankin S, Qu C, Zhang J, et al. Cooperativity within and among Pten, p53, and Rb pathways induces high-grade astrocytoma in adult brain. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu C, Sage JC, Miller MR, Verhaak RG, Hippenmeyer S, Vogel H, et al. Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals tumor cell of origin in glioma. Cell. 2011;146:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alcantara Llaguno SR, Wang Z, Sun D, Chen J, Xu J, Kim E, et al. Adult lineage-restricted CNS progenitors specify distinct glioblastoma subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghazi SO, Stark M, Zhao Z, Mobley BC, Munden A, Hover L, et al. Cell of origin determines tumor phenotype in an oncogenic Ras/p53 knockout transgenic model of high-grade glioma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:729–740. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182625c02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zong H. Generation and applications of MADM-based mouse genetic mosaic system. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1194:187–201. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1215-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zong H, Espinosa JS, Su HH, Muzumdar MD, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with double markers in mice. Cell. 2005;121:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edmondson R, Broglie JJ, Adcock AF, Yang L. Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2014;12:207–218. doi: 10.1089/adt.2014.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan X, Jörg DJ, Cavalli FMG, Richards LM, Nguyen LV, Vanner RJ, et al. Fate mapping of human glioblastoma reveals an invariant stem cell hierarchy. Nature. 2017;549:227–232. doi: 10.1038/nature23666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ledur PF, Liu C, He H, Harris AR, Minussi DC, Zhou HY, et al. Culture conditions tailored to the cell of origin are critical for maintaining native properties and tumorigenicity of glioma cells. Neuro-Oncology. 2016;18:1413–1424. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreedharan S, Maturi NP, Xie Y, Sundström A, Jarvius M, Libard S, et al. Mouse models of pediatric supratentorial high-grade glioma reveal how cell-of-origin influences tumor development and phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77:802–812. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Y, Marinescu VD, Xie Y, Jarvius M, Maturi NP, Haglund C, et al. Glioblastoma cell malignancy and drug sensitivity are affected by the cell of origin. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1080–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batich KA, Reap EA, Archer GE, Sanchez-Perez L, Nair SK, Schmittling RJ, et al. Long-term Survival in glioblastoma with cytomegalovirus pp65-targeted vaccination. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1898–1909. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]