Abstract

The true clinical significance of Lodderomyces elongisporus remains underestimated as a result of problems associated with its identification by the VITEK 2 yeast identification system. Here we describe a case of L. elongisporus primary progressive fungaemia in a woman with no known risk factors for invasive fungal infections. The isolate was identified by PCR sequencing of the internally transcribed spacer region of ribosomal DNA. Despite treatment with caspofungin, the patient died within 3 days of onset of fungaemia. Our literature review highlights this organism's emerging role as a bloodstream pathogen. A need for application of molecular methods for its accurate identification is emphasized.

Keywords: Ascospores, bloodstream pathogen, emerging significance, lodderomyces elongisporus, molecular identification

Introduction

Lodderomyces elongisporus was considered as a sexual state of Candida parapsilosis [1], and its role in human infection was unknown until recently. Sequencing of the ribosomal RNA gene revealed that L. elongisporus represents a distinct species [2]. The aetiologic role of L. elongisporus was subsequently established in human infections [3]. Of ten clinical isolates identified as L. elongisporus, eight originated from Mexico, while one each came from China and Malaysia [4]. These isolates were previously misidentified as C. parapsilosis by the VITEK 2 yeast identification system. L. elongisporus has been isolated from bloodstream and from the catheter tip of a case of suspected fungaemia patient in Kuwait [3], [4], [5].

Here we describe a case of primary fungaemia by L. elongisporus that progressed rapidly with fatal outcome despite prompt initiation of treatment with caspofungin.

Case summary

A 71-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease was brought to emergency room in an unconscious state. Head computed tomographic scan revealed a stroke. On day 2, her condition deteriorated rapidly, requiring inotropic support. She developed septic shock, as indicated by elevated levels of inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 70 mm/h; C-reactive protein, 78 mg/L). Blood obtained at this time grew a yeast in both aerobic and anaerobic BacT/ALERT culture bottles. Pending identification, caspofungin was administered immediately, but she died on day 3 of her hospital stay.

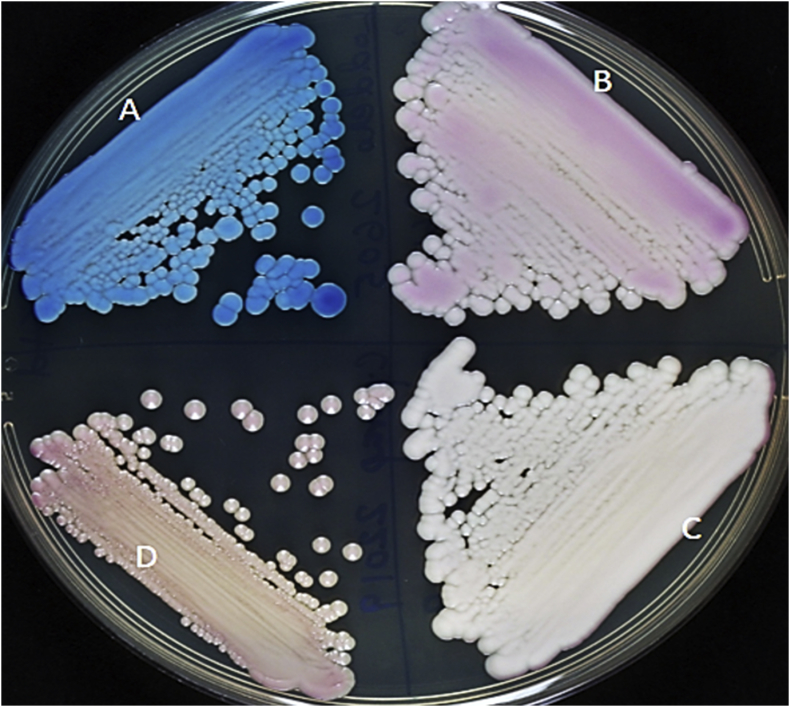

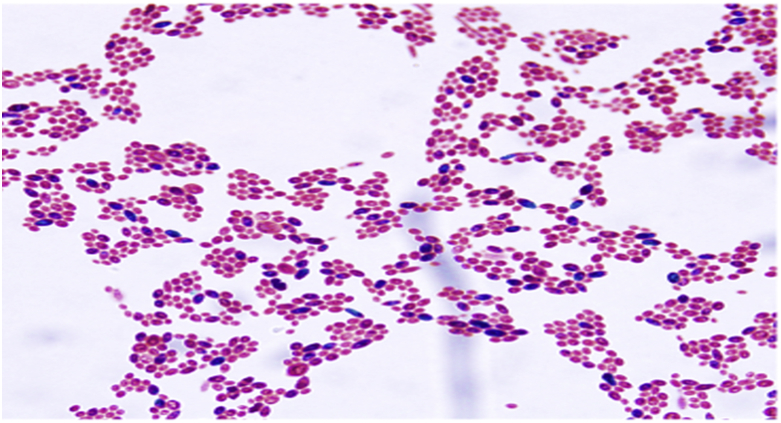

The yeast isolate (Kw553/18) was identified as C. parapsilosis by the VITEK 2 yeast identification system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). The isolate was referred to the Mycology Reference Laboratory for further characterization. On CHROMagar Candida (CHROMagar, Paris, France), it produced turquoise blue colonies (Fig. 1) instead of cream-coloured colonies with a pinkish shade, which is characteristic of C. parapsilosis, thus prompting further identification. On acetate ascospore agar after 7 days of incubation at 25°C, the isolate formed long ellipsoidal-shaped ascospores (Fig. 2), suggesting its identity as L. elongisporus. The internally transcribed spacer region of ribosomal DNA was amplified and sequenced as described previously [6], [7]. DNA sequence data comparisons of Kw553/18 (European Molecular Biology Laboratory accession no. LS482924) showed complete (100%) identity with the corresponding sequence from L. elongisporus type strain (ATCC 11503) but only 83% identity with the sequence from reference C. parapsilosis strain (ATCC 22019) [8]. The findings also suggested that Candida species isolates forming turquoise blue colonies on CHROMagar Candida and producing ascospores on acetate ascospore agar can be presumptively identified as L. elongisporus for laboratories where molecular identification methods are not available.

Fig. 1.

Colony characteristics of Lodderomyces elongisporus (Kw553/18) (A), Candida metappsilosis (B), C. orthopsilosis (C) and C. parapsilosis (D) on CHROMagar Candida. Note turquoise blue colonies of L. elongisporus.

Fig. 2.

Ellipsoidal to elongate ascospores (green) of Lodderomyces elongisporus produced on acetate ascospore agar and stained with Schaeffer-Fulton stain. Original magnification, ×1000.

Antifungal susceptibility was determined by Etest (bioMérieux) on RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% glucose, as described previously [9]. MIC values (μg/mL) were as follows: amphotericin B, 0.012; fluconazole, 0.125; voriconazole, 0.004; posaconazole, 0.003; itraconazole, 0.008; flucytosine, 0.064; caspofungin, 0.064; micafungin, 0.003.

Results

The unusual aspect of our case is that there were no apparent risk factors in the patient when fungaemia was diagnosed. However, she had a history of heart disease and had also experienced a stroke. She was not receiving any antibiotics; nor had any central lines been emplaced. She was hospitalized earlier for lower limb ischaemia due to peripheral vascular disease, but she was discharged 2 weeks before the current episode. It is not clear how she developed fungaemia as a result of this unusual yeast in the absence of any known risk factors. However, the possibility of inoculation of the yeast from the skin or translocation from the gastrointestinal tract cannot be ruled out.

Although L. elongisporus is a recognized bloodstream pathogen [3], little is known about its virulence attributes or its environmental niche. Like other opportunistic yeast pathogens, this species is also capable of causing diverse clinical conditions, including endocarditis. The species has a global prevalence: it has been isolated from patients in distant geographic regions, including Mexico, Malaysia and China [3], Australia [10], the Middle East [5], [11], Japan [12], Spain [13] and Korea [14] (Table 1, Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of salient findings of published cases of Lodderomyces elongisporus fungaemia

| Case no. | Study | Country | Age/sex | Comorbidities or risk factors | Identification method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Daveson 2012 [10] | Australia | 30/M | Endocarditis, osteomyelitis and brain embolic lesions; intravenous drug user |

|

| 2a | Ahmad 2013 [5] | Kuwait | 63/M | Cardiovascular attack, vascular catheter |

|

| 3 | Taj-Aldeen 2014 [11] | Qatar | 22/M | Trauma |

|

| 4 | Hatanaka 2016 [12] | Japan | 39/M | Thoracoabdominal aortic replacement complicated with aortoesophageal fistula, catheter |

|

| 5 | Fernández-Ruiz 2017 [13] | Spain | 79/M | COPD, diabetes mellitus, ESRD |

|

| 6 | Lee 2018 [14] | Korea | 56/F | Lung cancer, receiving immunosuppressive agents, vascular catheter |

|

| 7 | Present case | Kuwait | 71/F | Hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease |

|

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ITS, internally transcribed spacer; MALDI-TOF MS, matrix-assisted desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry; rDNA, recombinant DNA.

In case 2, L. elongisporus was isolated from catheter tip culture.

Table 2.

Treatment and outcome of Lodderomyces elongisporus fungaemia

| Case no. | Study | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Daveson 2012 [10] | Caspofungin before cardiac surgery, then amphotericin B plus flucytosine followed by voriconazole | Survived |

| 2a | Ahmad 2013 [5] | Fluconazole | Survived |

| 3 | Taj-Aldeen 2014 [11] | Caspofungin, fluconazole | Died |

| 4 | Hatanaka 2016 [12] | Micafungin | Survived |

| 5 | Fernández-Ruiz 2017 [13] | Caspofungin 3 days | Died |

| 6 | Lee 2018 [14] | Not provided | Died before removal of indwelling catheter or antifungal treatment |

| 7 | Present case | Caspofungin (one dose) | Died |

In case 2, L elongisporus was isolated from catheter tip culture.

The salient findings of seven individual case reports of L. elongisporus fungaemia are summarized in Table 1, Table 2. All patients had associated comorbidities and/or risk factors including an intravenous drug user (patient 1). Four (57.5%) of seven patients died even though six patients were treated with antifungal drugs. Because the number of patients is small, it is difficult to assess the impact of antifungal therapy on the outcome. It is also not clear if use of echinocandins (caspofungin in four patients and micafungin in one patient) was an appropriate therapy for L. elongisporus fungaemia because three of five patients died.

Discussion

Data on antifungal susceptibility of L. elongisporus are scanty, and no susceptibility breakpoints are available. C. parapsilosis complex members, to which L. elongisporus is closely related, generally show reduced susceptibility to echinocandins [15]. The in vitro MIC values for antifungal drugs for L. elongisporus isolates were within the susceptible range (Table 3) [3], [5], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [16]. Although echinocandins have lower in vitro activity against C. parapsilosis complex members to which L. elongisporus is closely related, the current Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines still favour therapeutic use of echinocandins for the treatment of candidaemia caused by C. parapsilosis [17].

Table 3.

Antifungal susceptibility profile of Lodderomyces elongisporus isolates

| Study | No. of isolate | Method | MIC (μg/mL) of: |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | 5-FC | FL | IT | KE | VO | POS | ISA | CS | AND | MYC | |||

| Lockhart 2008 [3] | 9 | BMD, CLSI | 0.37–0.75 | NA | 0.12–0.025 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.015–0.03 | 0.015–0.12 | 0.015–0.03 |

| Tay 2009 [16] | 1 | Etest | 0.012 | NA | 0.125 | 0.047 | 0.003 | 0.004 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Daveson 2012 [10] | 1 | NA | 0.25 | 0.06 | ≤0.125 | 0.06 | ≤0.008 | ≤0.008 | 0.03 | NA | 0.03 | NA | NA |

| Ahmad 2013 [5] | 1 | Etest | NA | 0.094 | 0.32 | NA | NA | 0.002 | 0.023 | NA | 0.094 | NA | NA |

| Taj-Aldeen 2014 [11] | 1 | BMD, CLSI | 0.5 | NA | 0.25 | 0.031 | NA | <0.016 | 0.063 | <0.016 | 0.5 | 0.016 | NA |

| Hatanaka 2016 [12] | 1 | BMD, CLSI | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | NA | 0.015 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.015 |

| Fernández-Ruiz 2017 [13] | 1 | BMD, CLSI | 0.031 | 0.125 | NA | NA | 0.0017 | 0.007 | NA | NA | 0.015 | 0.015 | |

| Lee 2018 [14] | 1 | ATB Fungus 3 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | NA | NA | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0.25 | NA | 0.06 |

| Present case | 1 | Etest | 0.012 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | NA | 0.064 | 0.008 | 0.032 |

5-FC, 5-flurocytosin; AND, anidulafungin; AP, amphotericin; BMD, broth microdilution; CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; CS, caspofungin; FL, fluconazole; ISA, isavuconazole; IT, itraconazole; KE, ketoconazole; MYC, micafungin; NA, not available; POS, posaconazole; VO, voriconazole.

Uncommon yeast pathogens are often misidentified as a result of limitations of the currently available commercial yeast identification systems, such as VITEK 2, which identify C. parapsilosis complex but do not distinguish C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, C. metapsilosis and L. elongisporus [18]. A retrospective characterization of 380 C. parapsilosis complex isolates available in the Mycology Reference Laboratory culture collection and previously speciated by VITEK 2 by a multiplex PCR assay [19] that simultaneously detected C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, C. metapsilosis and L. elongisporus identified three L. elongisporus isolates. One isolate was obtained from sputum of a cancer patient (isolate Kw2486/06); another isolate (Kw554/08) was recovered from the catheter tip of a patient with fungaemia [5]; and a third isolate (Kw3047/14) was isolated from the bloodstream of a cancer patient. However, clinical details of the two cancer patients were not available. Recently matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry has also been used for the identification of L. elongisporus [20].

Rare yeast species often exhibit reduced susceptibility to one or more commonly used antifungal agents [18]. A number of factors have been attributed to their increased occurrence, such as prolonged survival of seriously ill patients admitted in intensive care units, administration of multiple broad-spectrum antibiotics, dependence on life support systems and extended use of intravascular catheters [21]. It is also possible that these relatively less susceptible yeasts take advantage of the selection pressure created by prophylactic and therapeutic use of antifungal agents, resulting in increased colonization and invasive infection [18], [21]. Perhaps a delay in accurate identification and a lack of experience in the management of such rare yeast infections pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges with consequently higher mortality rates.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the technical support of S. Varghese, S. Vayalil and O. Al-Musallam of Mycology Reference laboratory.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Hamajima K., Nishikawa A., Shinoda T., Fukazawa Y. Deoxyribonucleic acid base composition and its homology between two forms of Candida parapsilosis and Lodderomyces elongisporus. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1987;33:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 2.James S.A., Collins M.D., Roberts I.N. The genetic relationship of Lodderomyces elongisporus to other ascomycete yeast species as revealed by small-subunit rRNA gene sequences. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;19:311. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1994.tb00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockhart S.R., Messer S.A., Pfaller M.A., Diekema D.J. Lodderomyces elongisporus masquerading as Candida parapsilosis as a cause of bloodstream infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:374–376. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01790-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockhart S.R., Messer S.A., Pfaller M.A., Diekema D.J. Geographic distribution and antifungal susceptibility of the newly described species Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis in comparison to the closely related species Candida parapsilosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2659–2664. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00803-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad S., Khan Z.U., Johny M., Ashour N.M., Al-Tourah W.H., Joseph L. Isolation of Lodderomyces elongisporus from the catheter tip of a fungemia patient in the Middle East. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:560406. doi: 10.1155/2013/560406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan Z.U., Ahmad S., Mokaddas E., Chandy R., Cano J., Guarro J. Actinomucor elegans var. kuwaitiensis isolated from the wound of a diabetic patient. Antonie van Leeuwoenhoek. 2008;94:343–352. doi: 10.1007/s10482-008-9251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan Z.U., Ahmad S., Hagen F., Fell J.W., Kowshik T., Chandy R. Cryptococcus randhawai sp. nov., a novel anamorphic basidiomycetous yeast isolated from tree trunk hollow of Ficus religiosa (peepal tree) from New Delhi, India. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2010;97:253–259. doi: 10.1007/s10482-009-9406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoch C.L., Seifert K.A., Huhndorf S., Robert V., Spouge J.L., Levesque C.A. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6241–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asadzadeh M., Al-Sweih N.A., Ahmad S., Khan Z.U. Antifungal susceptibility of clinical Candida parapsilosis isolates in Kuwait. Mycoses. 2008;51:318–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daveson K.L., Woods M.L. Lodderomyces elongisporus endocarditis in an intravenous drug user: a new entity in fungal endocarditis. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1338–1344. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.047548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taj-Aldeen S.J., AbdulWahab A., Kolecka A., Deshmukh A., Meis J.F., Boekhout T. Uncommon opportunistic yeast bloodstream infections from Qatar. Med Mycol. 2014;52:552–556. doi: 10.1093/mmycol/myu016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatanaka S., Nakamura I., Fukushima S., Ohkusu K., Matsumoto T. Catheter-related bloodstream infection due to Lodderomyces elongisporus. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2016;69:520–522. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández-Ruiz M., Guinea J., Puig-Asensio M., Zaragoza Ó., Almirante B., Cuenca-Estrella M., CANDIPOP Project. GEI H-GEMICOMED (SEIMC) REIPI Fungemia due to rare opportunistic yeasts: data from a population-based surveillance in Spain. Med Mycol. 2017;55:125–136. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myw055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H.Y., Kim S.J., Kim D., Jang J., Sung H., Kim M.N. Catheter-related bloodstream infection due to Lodderomyces elongisporus in a patient with lung cancer. Ann Lab Med. 2018;38:182–184. doi: 10.3343/alm.2018.38.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanguinetti M., Posteraro B., Lass-Flörl C. Antifungal drug resistance among Candida species: mechanisms and clinical impact. Mycoses. 2015;58(Suppl. 2):2–13. doi: 10.1111/myc.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tay S.T., Na S.L., Chong J. Molecular differentiation and antifungal susceptibilities of Candida parapsilosis isolated from patients with bloodstream infections. Med Microbiol. 2009;58(Pt 2):185–191. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.004242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pappas P.G., Kauffman C.A., Andes D.R., Clancy C.J., Marr K.A., Ostrosky-Zeichner L. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e1–e50. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan Z., Ahmad S. Candida auris: an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen of global significance. Clin Med Res Pract. 2017;7:240–248. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asadzadeh M., Ahmad S., Hagen F., Meis J.F., Al-Sweih N., Khan Z. Simple, low-cost detection of Candida parapsilosis complex isolates and molecular fingerprinting of Candida orthopsilosis strains in Kuwait by ITS region sequencing and amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Carolis E., Hensgens L.A., Vella A., Posteraro B., Sanguinetti M., Senesi S. Identification and typing of the Candida parapsilosis complex: MALDI-TOF MS vs. AFLP. Med Mycol. 2014;52:123–130. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myt009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miceli M.H., Díaz J.A., Lee S.A. Emerging opportunistic yeast infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:142–151. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]