Abstract

Cervical adenocarcinomas are believed to lose estrogen response on the basis of no expression of a nuclear estrogen receptor such as ERα in clinical pathology. Here, we demonstrated that cervical adenocarcinoma cells respond to a physiological concentration of estrogen to upregulate claudin-1, a cell surface molecule highly expressed in cervical adenocarcinomas. Knockout of claudin-1 induced apoptosis and significantly inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion of cervical adenocarcinoma cells and tumorigenicity in vivo. Importantly, all of the cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines examined expressed a membrane-bound type estrogen receptor, G protein–coupled receptor 30 (GPR30/GPER1), but not ERα. Estrogen-dependent induction of claudin-1 expression was mediated by GPR30 via ERK and/or Akt signaling. In surgical specimens, there was a positive correlation between claudin-1 expression and GPR30 expression. Double high expression of claudin-1 and GPR30 predicts poor prognosis in patients with cervical adenocarcinomas. Mechanism-based targeting of estrogen/GPR30 signaling and claudin-1 may be effective for cervical adenocarcinoma therapy.

Introduction

The incidence of uterine cervical adenocarcinoma has been increasing worldwide, predominantly in young women, despite the fact that the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has been decreasing [1], [2]. It has been shown that adenocarcinoma has a worse prognosis than that of SCC at the same stage and with the same tumor size. The main reasons for the worse prognosis are a higher rate of metastases [3] and resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy [4]. Therefore, a new treatment strategy is needed to improve the outcome of cervical adenocarcinoma.

Estrogen is an important steroid hormone that plays a key role in development and function of the female reproductive tract. Estrogen binds to its receptor to activate downstream signaling pathways [5]. Estrogen receptors (ERs) include ERα, ERβ, and G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30). Classical types ERα and ERβ act as nuclear receptors for estrogen, whereas GPR30 localizes at the cell surface membrane for a rapid response to estrogen [6].

In the uterine cervix, non-neoplastic columnar epithelial cells are positive for classical ERs, whereas their expression is almost absent in adenocarcinomas [7], [8], [9], [10]. Based on the negative or weak immunoreactivity of ERs, cervical adenocarcinomas are distinguished from ER-positive endometrioid adenocarcinomas in the uterine corpus in clinical pathology. Furthermore, several studies demonstrated that classical ER expression was not associated with the prognosis or clinicopathological parameters of uterine cervical cancers [11], [12]. Therefore, cervical adenocarcinomas have been believed to be estrogen-insensitive neoplasms, and estrogen signaling has not been considered in the context of cervical adenocarcinomas.

We recently revealed that cervical adenocarcinomas highly express claudin-1 [13]. Claudin-1 is a tight junction protein that shows an altered expression pattern and is associated with proliferation, migration, and invasion in several cancers [14], [15]. Since little is known about the regulatory mechanism of its expression, we tried to elucidate the mechanism and found that estrogen stimulus clearly induced claudin-1 expression in cervical adenocarcinoma cells, contrary to the popular belief of their estrogen insensitivity.

In this study, we demonstrated that the membrane-bound type estrogen receptor GPR30 is highly expressed in cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines and surgical specimens of patients with cervical adenocarcinoma. In addition, we found that estrogen/GPR30 signaling contributed to malignant potentials of cervical adenocarcinoma by induction of a tumor-promoting claudin-1. We also found a positive correlation between GPR30 expression and claudin-1 expression in human surgical specimens. Our findings provide an insight into a new therapeutic strategy for cervical adenocarcinoma.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Reagents

The antibodies used are summarized in Table S1. Estradiol (E2) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO). PPT and DPN were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). AG1478, U0126, and LY294002 were from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (San Diego, CA). G1 and G15 were from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK).

Cell Line Culture and Treatment

The human cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines Hela229, and OMC4 were purchased from RIKEN Bio-Resource Center (Tsukuba, Japan), and HCA1 was from JCRB cell bank (Osaka, Japan). The human cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines CAC-1 and TMCC1 were provided by our colleague Dr. Hayakawa [16], [17]. Cells were maintained in DMEM F-12 HAM (OMC4), EMEM (HCA-1), or RPMI-1640 (CAC-1 and TMCC1) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 20% (OMC4) or 10% (the others) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). The medium for all cell lines contained 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The medium for OMC4 also contained 50 μg/ml amphotericin B. All cells were plated on collagen-coated 35- and 60-mm culture dishes and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Cervical adenocarcinoma cells were treated with estradiol or G1 in medium without FBS. Some cells were pretreated with the inhibitors G15, AG1478, U0126, and LY294002 for 30 minutes before treatment with estradiol or G1.

Immunocytochemistry of Cell Blocks and Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cell blocks were prepared by using the sodium alginate method [18]. Briefly, cells were collected, washed with PBS, and fixed in 10% formalin solution for 12-24 hours at 4°C. The fixative was discarded after centrifugation, and aggregated cells were gently suspended in 1% sodium alginate solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Then, 1 M CaCl2 was added to form a gel, and the fixed cell-containing gel was embedded in paraffin. Thin sections (4 μm) were cut from paraffin-embedded cell blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Deparaffinized sections were immersed in 10 mmol/l sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and autoclaved for antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using methanol containing 0.03% H2O2. After incubation with a blocking buffer [0.01 mol/l PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma)], the sections were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-Ki-67 (1:100, BioGenex) or anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology) at 4°C. Immunocytochemical labeling was visualized using the EnVision system according to the manufacturer's protocol [19]. The sections were counterstained with Meyer's hematoxylin. Immunofluorescence was performed as described previously [20].

RNA Interference

Human GPR30-specific siRNA and siRNA universal negative control were purchased from Sigma. Sequences of GPR30-siRNA are 5′-CAAUACGUUAUUGGGCUUUUU-3′ and 5′-AAAGCCCAAUAACGUAUUGUU-3′. Transfection of siRNA was performed using RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Gene Targeting by the CRISPR/Cas-9 System

The guide RNA (gRNA) target site was searched for by using the free software CRISPR direct [21]. The sequence of the target site for the human claudin-1 locus is 5′-CAACAGCTGCAGCCCCGCGTTGG-3′. A vector expressing noncoding gRNA, orange fluorescent protein (OFP), and Cas9 nuclease was constructed by using a GeneArt CRISPR Nuclease Vector Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were transfected with the vector by using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Two days after transfection, OFP-positive cells were sorted by FACS Aria (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Loss of claudin-1 protein expression was screened by Western blotting using anti–claudin-1 antibody. After screening, genomic DNA was extracted from candidate clones by using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and then DNA fragments around gRNA target site were amplified with PCR by using primers as follows: 5′-CAACCGCAGCTTCTAGTATCCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTCAGATTCAGCAAGGAGTCAAAG-3′ (reverse). PCR products were cloned into pGEMT-easy vector (Promega) and then analyzed by sequencing with the forward primer. In the screened clones, cells expressing an amount of claudin-1 comparable to that in wild-type cells were used as controls.

Cell Proliferation Assay

BrdU incorporation assay was performed as described previously [19]. In the WST-8 assay, cells were seeded in 96-well plates, and their viability was assessed at 24 hours after incubation by using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm was measured by using a Bio-Rad Model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). To determine the effect of claudin-1 knockout on cell proliferation, cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes at a density of 2 × 105 cells/dish and cultivated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C. At 48, 72, 96, and 144 hours after incubation, cells were collected, and the total cell number was counted under an inverted microscope. Each experiment was independently repeated three times.

Plate Colony-Forming Assay

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1000 cells per well. After incubation for 10-14 days, the cells were fixed with methanol for 15 minutes and stained with 0.04% crystal violet for 15 minutes at room temperature. The colony was defined as at least 50 cells. Visible colonies were counted. Each experiment was independently repeated six times.

Cell Migration and Invasion Assay

The migration assay was performed using Transwell (Corning; 8-μm pore polycarbonate membrane insert) in 24-well dishes. Biocoat Matrigel (Corning; pore size, 8 μm) was used to evaluate cell invasion potential. Briefly, cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in the upper chamber in a serum-free medium. The lower chamber contained a medium with 10% FBS. The chambers were incubated for 12-24 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2, and then the cells were fixed and stained with 0.04% crystal violet in 2% ethanol for 5 minutes. Nonmigrating or noninvading cells were removed from the upper side of the filters by scrubbing with cotton swabs, and the filters were washed with PBS. Cells that had migrated or invaded on the lower side of the filters were examined and counted under a microscope. Each experiment was independently repeated three times.

Mouse Xenograft Model

Claudin-1 knockout or control TMCC1 cells (1 × 106) were collected in 100 μl of PBS and then mixed with 100 μl of Matrigel (Corning). The cell/Matrigel mixture was subcutaneously injected into the flanks of 6-week-old BALB/c nude mice. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring tumor volume (mm3) calculated as length × (width2/2). On the final day, tumors were resected and their weights were measured. All procedures involving animals and their care were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of our institute.

Immunohistochemistry of Surgical Specimens

Specimens of 53 cases of cervical adenocarcinoma including adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) obtained by surgical resections during the period from 2004 to 2012 were retrieved from the pathology file of Sapporo Medical University Hospital, Sapporo, Japan. As controls, adjacent non-neoplastic regions were examined as normal tissues (n = 44). Clinicopathological features of the patients were described previously [13]. The protocol for human study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient who participated in the investigation. Immunohistochemistry was performed with anti–claudin-1 (1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or anti-GPR30 antibody (1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described previously [13]. The intensity of staining was assessed as strong (3), moderate (2), weak (1), or negative (0). The proportions of positively stained tumor cells were recorded as 0 (no staining), 1 (1%-10%), 2 (11%-20%), 3 (21%-30%), 4 (31%-40%), 5 (41%-50%), 6 (51%-60%), 7 (61%-70%), 8 (71%-80%), 9 (81%-90%), and 10 (91%-100%). We used an immunoreactive score (IRS) (i.e., intensity 3 × proportion 10 = IRS 30, scale of 0 to 30) for improvement in accuracy. All slides were independently evaluated by two pathologists (A. T. and M. M.). Discordant cases were discussed, and a consensus was reached.

Statistical Analysis

The measured values are presented as means ± SD. Data were analyzed and compared using the unpaired two-tailed Student's t test, Fisher's exact test, and Kruskal-Wallis test. Survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Statistical significance was accepted when P < .05. A single asterisk (*) and a double asterisk (**) represent P < .05 and P < .01, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed with EZR software [22].

Results

Claudin-1 Is Overexpressed in Human Cervical Adenocarcinoma Cell Lines

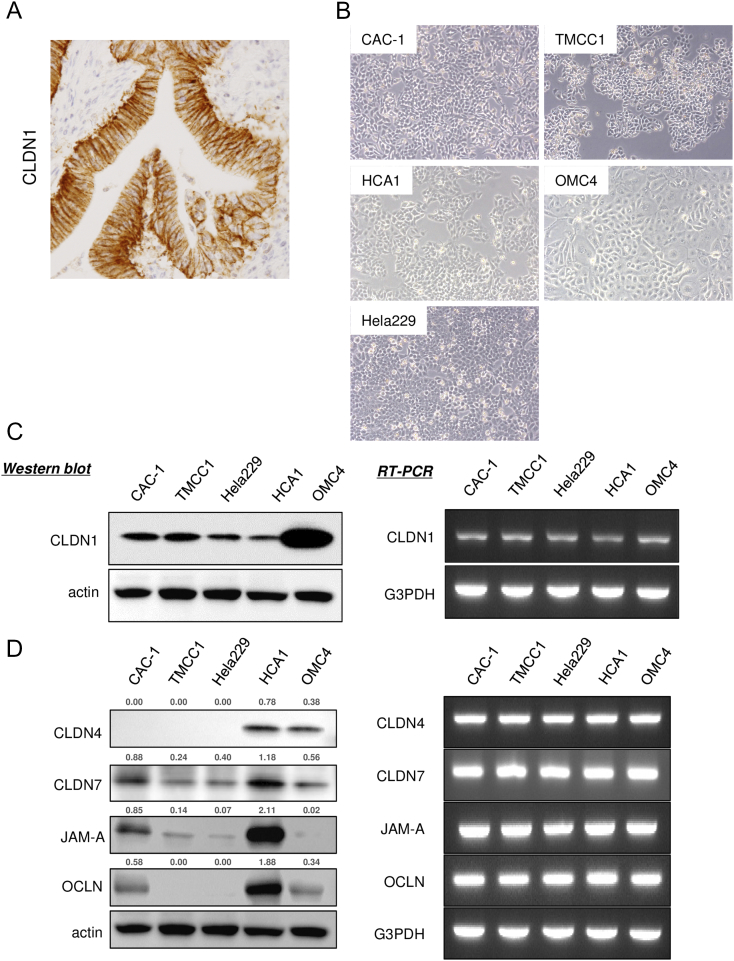

We previously reported that claudin-1 expression was significantly higher in cervical AIS and adenocarcinoma than in normal endocervical glands in surgical specimens (Figure S1A and [13]). To understand the regulatory mechanism of claudin-1 and its role in cervical adenocarcinomas, we examined the human cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines CAC-1, TMCC1, Hela229, HCA1, and OMC4 (Figure S1B). At first, we confirmed the expression patterns of claudin-1 and other tight junction molecules in the cell lines because they have not been described elsewhere. Western blotting showed that the claudin-1 protein level was high in all of the tested cell lines, especially in the well-differentiated cell line OMC4 (Figure S1C). Claudin-4, claudin-7, JAM-A, and occludin proteins were detected, but these tight junction proteins were variously expressed in cervical adenocarcinoma cells (Figure S1D). Claudin-1 mRNA and mRNAs of the other tight junction molecules were detected by RT-PCR in all of the cell lines (Figure S1, C and D).

Figure S1.

Expression profile of claudin-1 and other tight junction proteins in cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines. Expression profile of claudin-1 and other tight junction proteins in cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines. (A) Immunohistochemical staining for claudin-1 in surgical specimen of human cervical adenocarcinoma. (B) Phase-contrast microscopy of cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines CAC-1, TMCC1, Hela229, HCA1, and OMC4. (C) Expression pattern of claudin-1 in human cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines. Western blotting (left panels) and RT-PCR (right panels). (D) Expression profile of tight junction proteins. Western blotting (left panels) and RT-PCR (right panels). The relative intensity of each band is shown over each immunoblot after normalization for the levels of actin. CLDN1: claudin-1, OCLN: occludin.

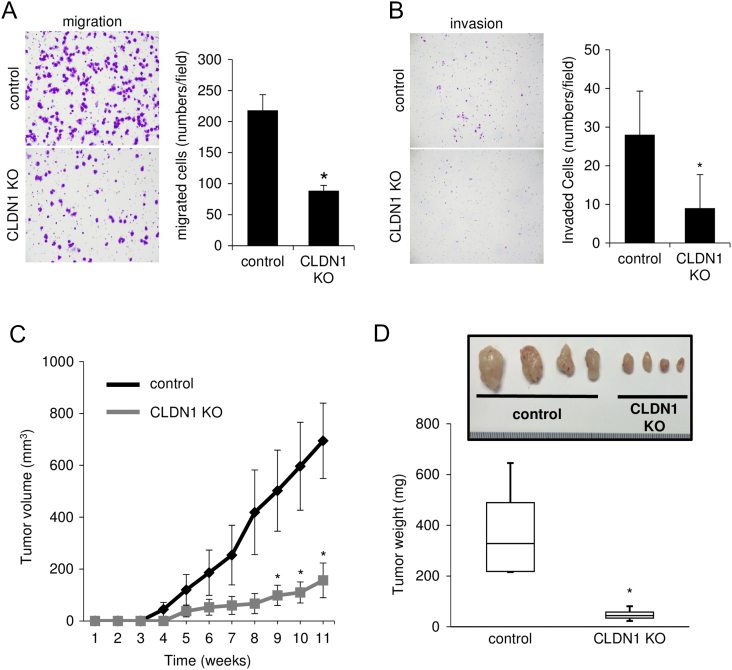

Claudin-1 Contributes to Malignant Potentials of Cervical Adenocarcinoma Cells

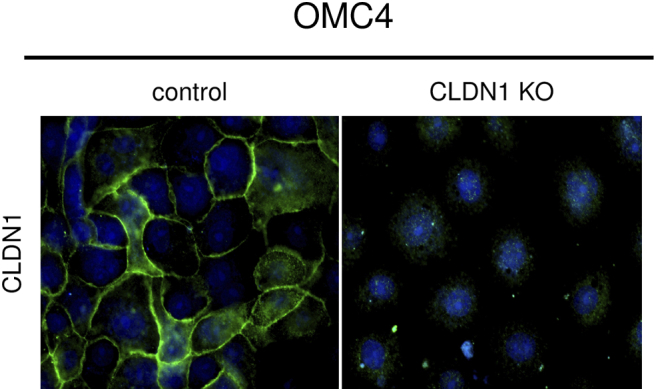

To determine whether claudin-1 expression has a role in malignant potentials, we established human cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines OMC4 (well-differentiated cell line) and TMCC1 (poorly differentiated cell line) with claudin-1 knockout (KO) by using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Claudin-1 KO cells were successfully identified by Western blot analysis using anti–claudin-1 antibody as cells without claudin-1 protein expression (Figure 1A). In immunostaining, claudin-1 KO cells showed no significant staining with anti–claudin-1 antibody, whereas control cells were strongly immunostained with the antibody predominantly in cell-cell contacts (Figure S2). Loss of claudin-1 expression resulted from various gene editing around the translational start codon of the claudin-1 gene in claudin-1 KO cells (data not shown). KO of claudin-1 did not affect the expression patterns of tight junction proteins, claudin-4, claudin-7, occludin, and JAM-A (data not shown).

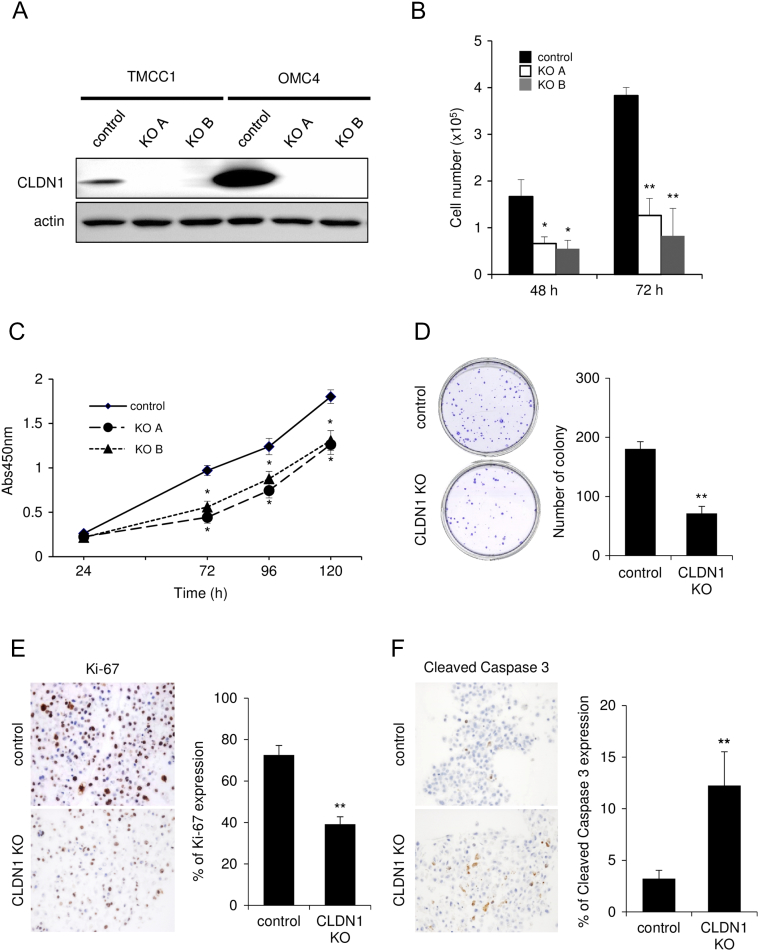

Figure 1.

Knockout of claudin-1 by the CRISPR-Cas9 system inhibits proliferation of cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A) CLDN1 KO TMCC1 and OMC4 cells were established using the CRISPR-cas9 system. (B-E) CLDN1 KO significantly inhibited proliferation of TMCC1 cells in multiple assays including cell count (B), WST-8 assay (C), colony formation assay (D), and immunostaining with anti–Ki-67 (proliferation marker) antibody (E). (F) Immunostaining with anti–cleaved caspase 3 (apoptosis marker) antibody. (A) Western blotting. The relative intensity of each band is shown over each immunoblot after normalization for the levels of actin. *P < .05, **P < .01. CLDN1: claudin-1.

Figure S2.

Knockout of claudin-1 by the CRISPR-Cas9 system in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. Immunofluorescence of CLDN1 (green) was absent in CLDN1 KO OMC4 cells. CLDN1: claudin-1, KO: knockout.

Next, we evaluated the effect of claudin-1 KO in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. During the course of cell culture, we found that claudin-1 KO TMCC1 and OMC4 cells grew more slowly than did control cells (Figures 1B and S3A). In the WST-8 cell proliferation assay, claudin-1 KO significantly inhibited proliferation of TMCC1 cells (at 72 hours after seeding) (Figure 1C). In the colony formation assay, the number of colonies was significantly smaller for claudin-1 KO cells than for control cells (Figures 1D and S3B). The percentage of Ki-67–positive cells, an indicator of proliferating cells, was lower for claudin-1 KO cells than for control cells (Figures 1E and S3C). In addition, the number of cleaved caspase-3–positive cells, an indicator of apoptosis, was larger for claudin-1 KO cells than for control cells (Figures 1F and S3D). These results indicated that claudin-1 KO inhibits cell proliferation, partially due to increased apoptosis, in cervical adenocarcinoma cells.

Figure S3.

Knockout of claudin-1 inhibits proliferation of cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A-D) CLDN1 KO significantly inhibited proliferation of OMC4 cells in multiple assays, including cell count (A), colony formation assay (B), and immunostaining with anti–Ki-67 (proliferation marker) antibody (C). (D) Immunostaining with anti–cleaved caspase 3 (apoptosis marker) antibody. *P<.05, **P<.01. CLDN1 KO: claudin-1 knockout.

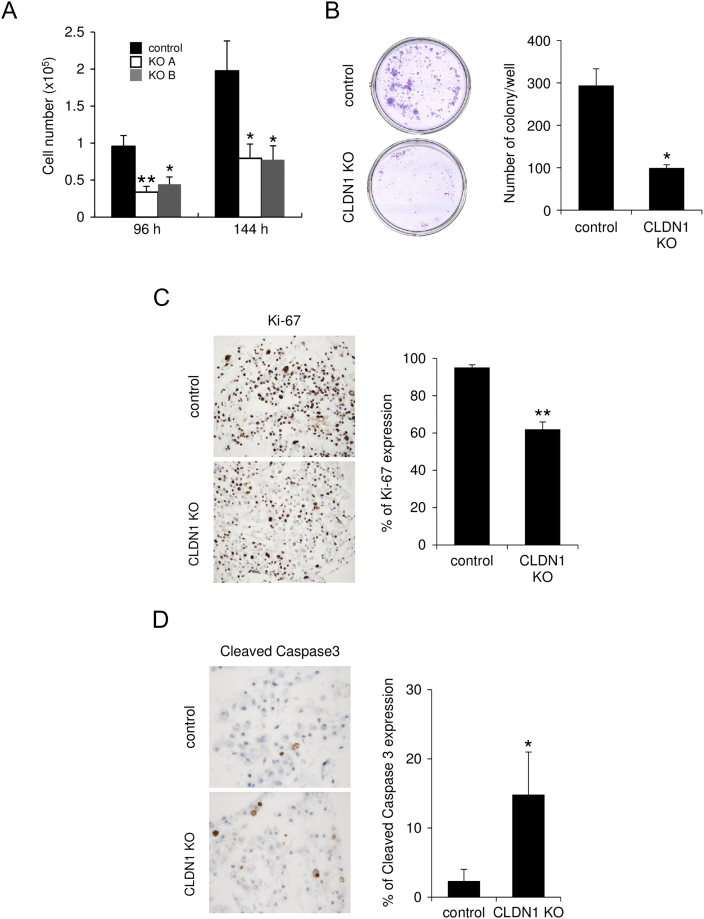

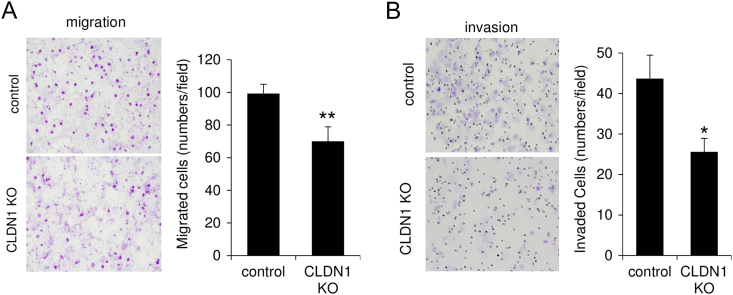

In a migration assay using a Transwell membrane, the number of claudin-1 KO cells migrating through the membrane was significantly smaller than that of control cells (Figures 2A and S4A). In an invasion assay using a Matrigel matrix-coated chamber, the number of claudin-1 KO cells penetrating through the matrix was significantly smaller than that of control cells (Figures 2B and S4B). In a mouse xenograft model, tumors derived from claudin-1 KO cells developed more slowly than did tumors derived from control cells (Figure 2C). Resected tumor weight at day 77 was significantly smaller for tumors derived from claudin-1 KO cells than for tumors derived from control cells (Figure 2D, P < .001). These results indicated that claudin-1 contributes to malignant potentials of cervical adenocarcinoma cells including cell proliferation, invasion, migration, and in vivo tumorigenesis.

Figure 2.

Knockout of claudin-1 inhibits migration, invasion, and in vivo tumorigenesis of cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A) Transwell migration assay. CLDN1 KO significantly inhibited migration of TMCC1 cells. (B) Matrigel invasion assay. CLDN1 KO significantly inhibited invasion of TMCC1 cells. (C) Growth rate of subcutaneously injected TMCC1 cells was slowed by CLDN1 KO compared to that of control cells in immune-suppressed mice. (D) Resected tumor weight was significantly smaller for tumors from CLDN1 KO cells than for tumors from control cells. *P < .05. CLDN1: claudin-1.

Figure S4.

Knockout of claudin-1 inhibits migration and invasion of cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A) Transwell migration assay. CLDN1 KO significantly inhibited migration of OMC4 cells. (B) Matrigel invasion assay. CLDN1 KO significantly inhibited invasion of OMC4 cells. *P<.05, **P<.01. CLDN1 KO: claudin-1 knockout.

Estrogen Induces Claudin-1 Expression in Cervical Adenocarcinoma Cells

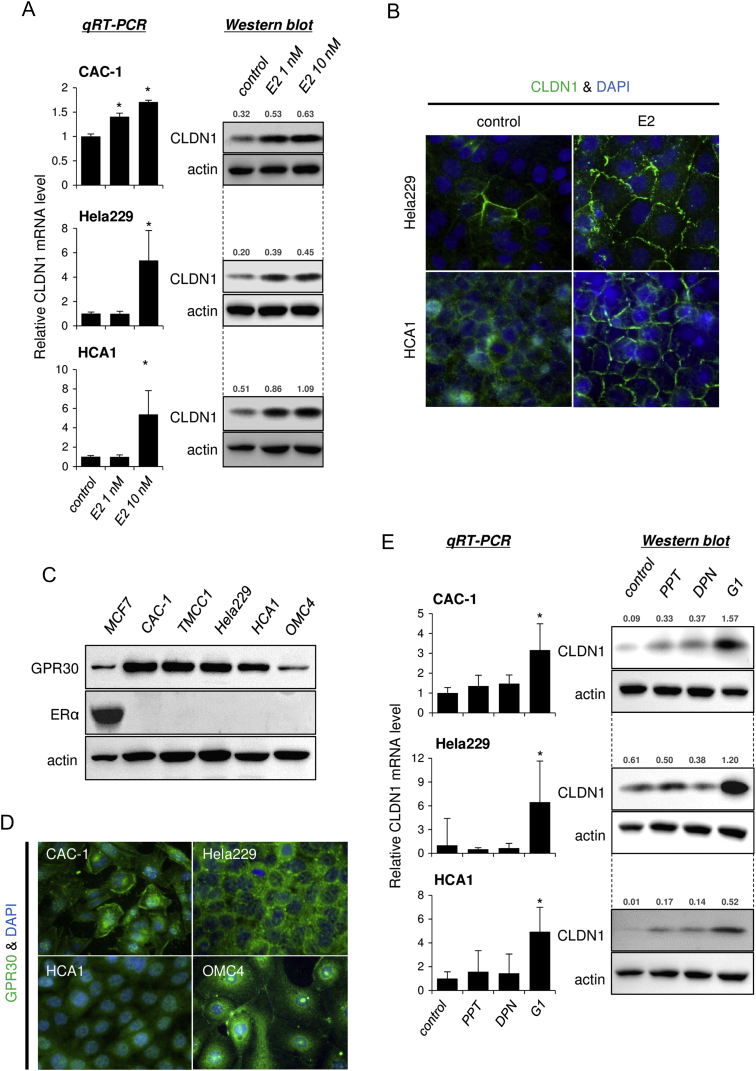

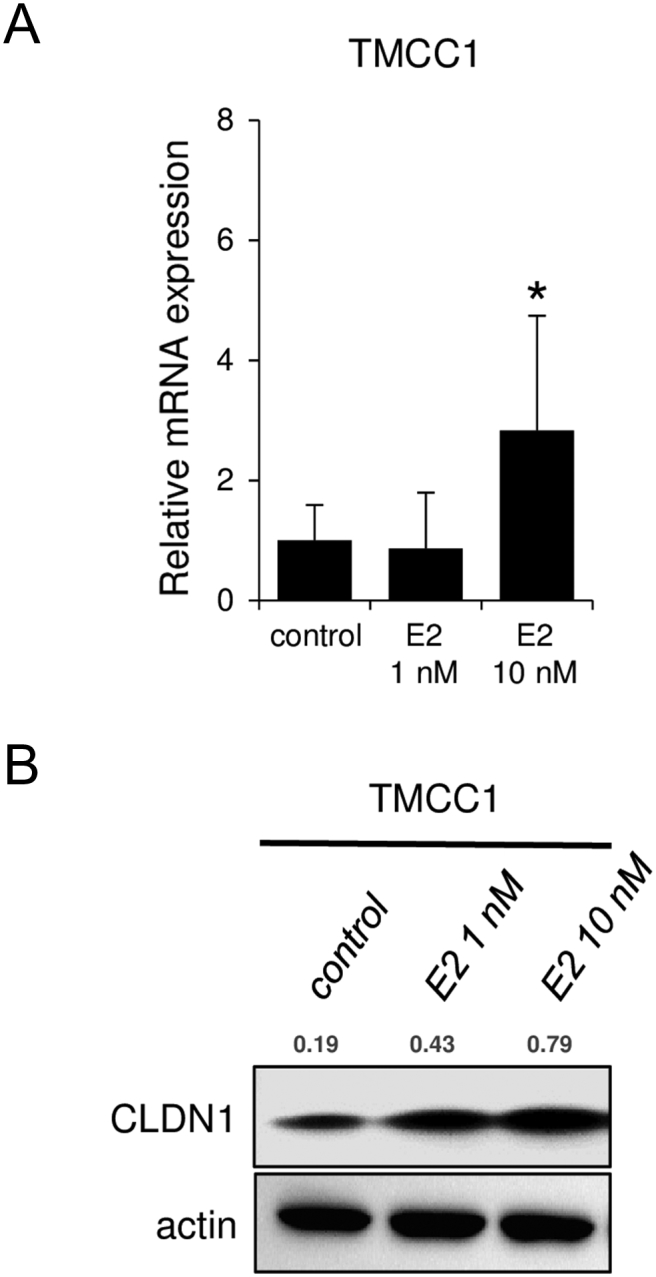

Next, we explored the molecular mechanisms responsible for claudin-1 overexpression in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. Surprisingly, we found that claudin-1 expression was induced by a physiological concentration of an estrogen, E2, in most of the tested cell lines (Figures 3, A and B, and S5). These results indicated that the cell lines are sensitive to estrogen stimulus, although cervical adenocarcinomas are generally believed to be estrogen-insensitive gynecological cancers without significant expression of classical ERs in pathological specimens [8], [9].

Figure 3.

Estrogen induces claudin-1 expression in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A) CLDN1 expression was induced by E2 treatment (24 hours) in CAC-1, Hela229, and HCA1 cells. (B) Immunofluorescence of CLDN1 (green) was induced by E2 treatment (10 nM, 24 hours) in HCA1 and Hela229 cells. (C) Expression profile of GPR30 (membrane-bound estrogen receptor) and ERα (classical estrogen receptor) in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. MCF7 cells (breast cancer cells) were used as a positive control for ERα expression. Western blotting. (D) Immunofluorescence of GPR30 (green) in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (E) CLDN1 expression was induced by G1 (GPR30 selective agonist), but not by PPT (ERα selective agonist) or DPN (ERβ selective agonist), treatment (10 nM, 24 hours) in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. The relative intensity of each band is shown over each immunoblot after normalization for the levels of actin. CLDN1: claudin-1.

Figure S5.

Estrogen induces claudin-1 expression in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. CLDN1 expression was induced by E2 treatment (24 hours) in TMCC1 cells. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR and (B) Western blotting of CLDN1. The relative intensity of each band is shown over each immunoblot after normalization for the levels of actin. CLDN1: claudin-1.

GPR30 Is a Key Estrogen Receptor for Estrogen-Dependent Claudin-1 Induction in Cervical Adenocarcinoma Cells

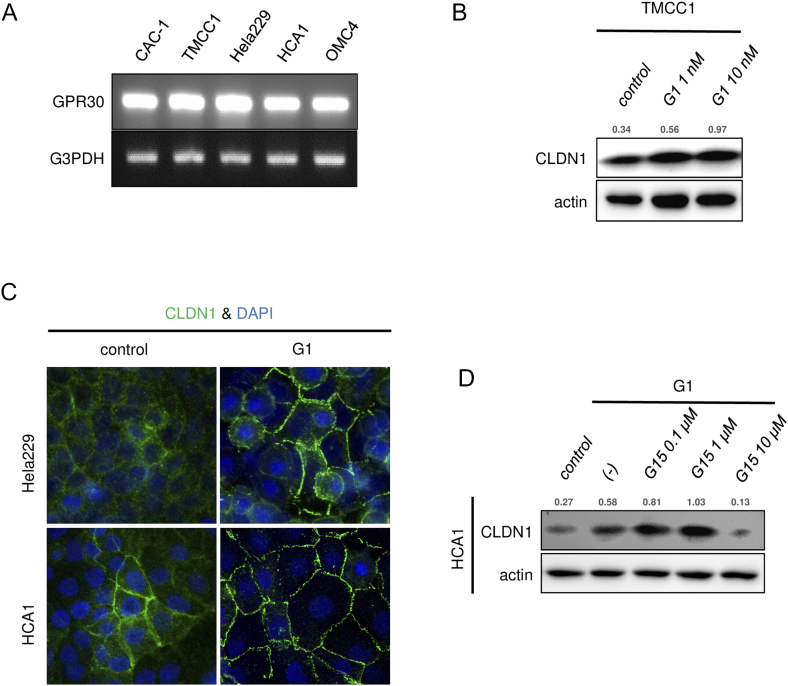

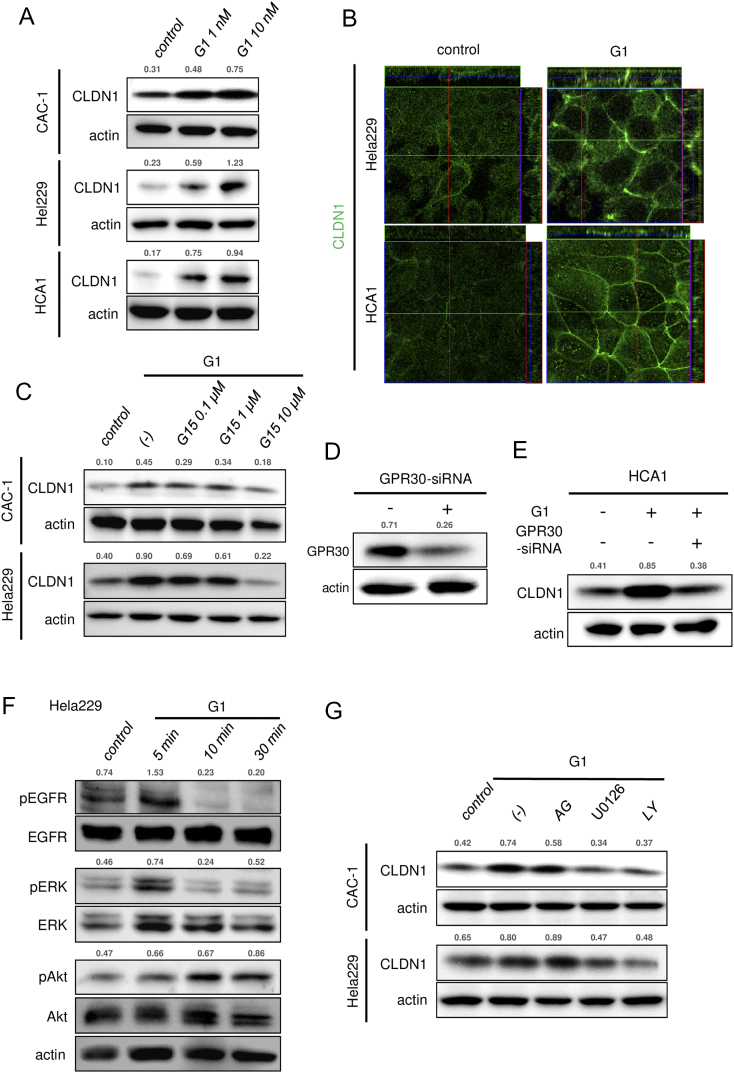

Consistent with the general pathological findings, none of the tested cell lines expressed classical ERα (Figure 3C), but all of the cell lines expressed significant levels of the membrane-bound estrogen receptor GPR30 (Figures 3, C and D, and S6A). To determine whether GPR30 mediates estrogen-dependent claudin-1 upregulation, the cells were exposed to agonists against three different estrogen receptor subtypes: ERα, ERβ, and GPR30. As expected from the dominant expression pattern of GPR30 subtype, G1 (GPR30-selective agonist) markedly upregulated claudin-1 mRNA expression and protein expression in all of the tested cell lines, whereas PPT (ERα-selective agonist) or DPN (ERβ-selective agonist) failed to effectively induce claudin-1 expression (Figure 3E). Similar to E2 stimulus, a low concentration of G1 (1 nM) was sufficient to induce claudin-1 expression (Figures 4A and S6B). Immunofluorescence also confirmed an increased level of claudin-1 after G1 stimulus at tight junctions and throughout the basolateral membrane (Figures 4B and S6C). The E2- and G1-dependent claudin-1 induction was suppressed by the GPR30 selective antagonist G15 (Figures 4C and S6D). Knockdown of GPR30 expression also inhibited G1-induced claudin-1 upregulation (Figure 4, D and E). These results indicated that estrogen-induced claudin-1 upregulation is achieved through GPR30 in cervical adenocarcinoma cells.

Figure S6.

GPR30 mediates estrogen-induced claudin-1 expression in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A) RT-PCR of GPR30 in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (B) CLDN1 expression was induced by G1 treatment (24 hours) in TMCC1 cells. Western blotting. (C) Immunofluorescence of CLDN1 (green) was induced by G1 treatment (10 nM, 24 hours) in Hela229 and HCA1 cells. (D) G1-induced CLDN1 expression was inhibited by pretreatment with G15 (GPR30 selective antagonist) for 24 hours in HCA1 cells. The relative intensity of each band is shown over each immunoblot after normalization for the levels of actin. CLDN1: claudin-1.

Figure 4.

GPR30 mediates induction of claudin-1 expression in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A) CLDN1 expression was induced by G1 treatment (24 hours) in CAC-1, Hela229, and HCA1 cells. (B) Immunofluorescence of CLDN1 was induced by G1 treatment (10 nM, 24 hours) in Hela229 and HCA1 cells. (C) G1-induced CLDN1 expression was inhibited by pretreatment with G15 (GPR30 selective antagonist) for 24 hours in CAC-1 and Hela229 cells. (D) GPR30 expression was knocked down by GPR30-specific siRNA in HCA1 cells. (E) G1-induced CLDN1 expression was inhibited by knockdown of GPR30 expression with GRP30-specific siRNA in HCA1 cells. (F) G1 treatment (10 nM) increased phosphorylation of ERK and Akt in Hela229 cells. (G) G1-induced CLDN1 expression was inhibited by pretreatment with U0126 (10 μM) and LY294002 (10 μM) in CAC-1 and Hela229 cells. (A, C-G) Western blotting and (B) confocal microscopy. The relative intensity of each band is shown over each immunoblot after normalization for the levels of actin. CLDN1: claudin-1.

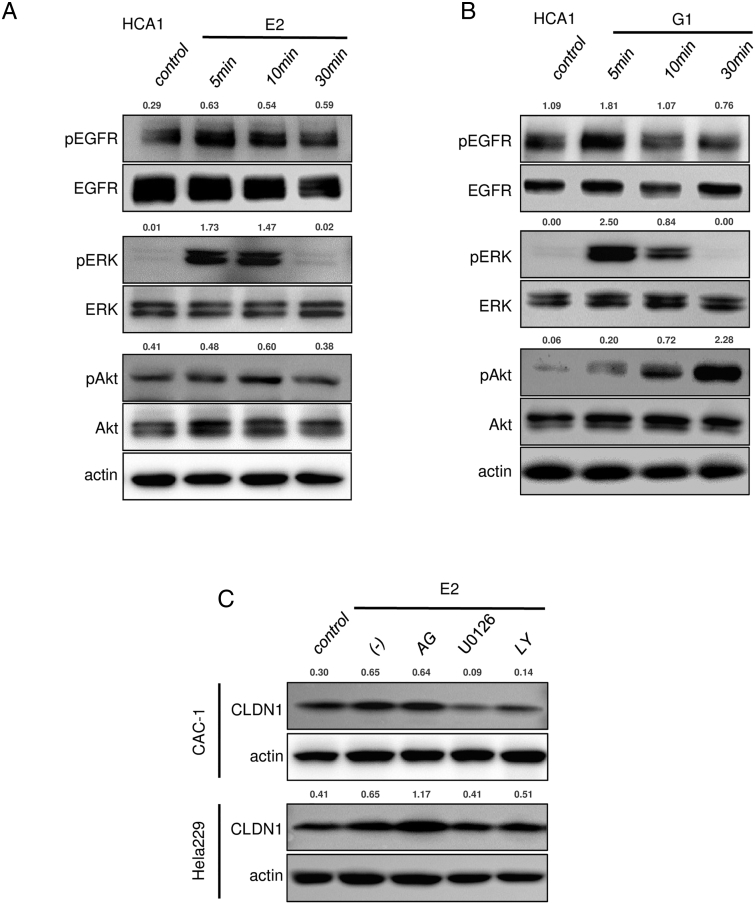

Estrogen/GPR30 Signaling Increases Claudin-1 Expression and Cell Proliferation via MAPK/ERK and Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase (PI3K)/Akt Signaling Pathways in Cervical Adenocarcinoma Cells

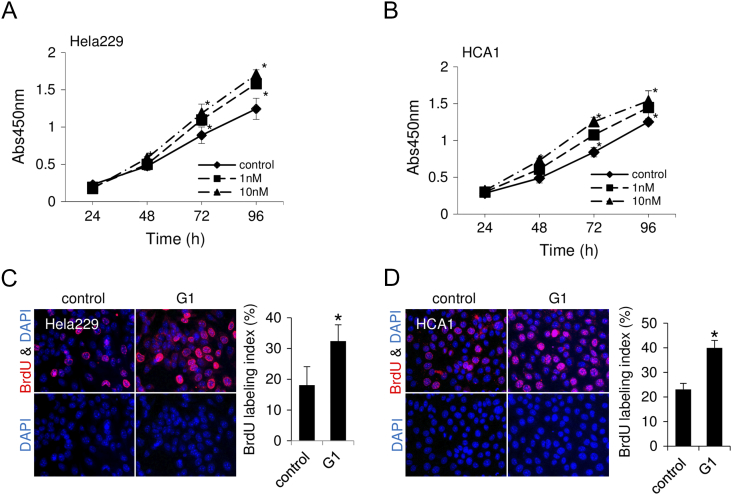

As previously reported in breast cancer cell lines [23], [24], estrogen stimulus activated EGFR/MAPK/ERK signaling in cervical adenocarcinoma cell lines (Figures 4F and S7, A and B). Both E2 and G1 rapidly increased phosphorylation levels of EGFR and ERK at 5 minutes after treatment and phosphorylation of Akt at 10 minutes (Figures 4F and S7, A and B), indicating that estrogen stimulus turns on proliferation-related signaling in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. Actually, G1 treatment significantly increased proliferation of cervical adenocarcinoma cells. In the WST-8 cell proliferation assay, the percentage of proliferative cells was significantly increased by G1 treatment (Figure 5, A and B). In BrdU labeling analysis, the ratio of BrdU-positive cells was significantly increased by G1 treatment (Figure 5, C and D).These results indicated that activation of GPR30 increased proliferation of cervical adenocarcinoma cells.

Figure S7.

ERK and/or Akt contribute to estrogen/GPR30 signaling in cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A-B) E2 and G1 treatment (10 nM) rapidly increased phosphorylation levels of EGFR, ERK, and Akt in HCA1 cells. (C) E2-induced CLDN1 expression was inhibited by pretreatment with U0126 (10 μM) and LY294002 (10 μM) in CAC-1 and Hela229 cells. Western blotting. The relative intensity of each band is shown over each immunoblot after normalization for the levels of actin. CLDN1: claudin-1.

Figure 5.

GPR30-specific agonist increases proliferation of cervical adenocarcinoma cells. (A-B) WST-8 assay. Cell proliferation was increased by G1 treatment in CAC-1 (A) and HCA1 (B) cells. (C-D) Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (red) was increased by G1 treatment (10 nM, 24 hours) in CAC-1 (C) and HCA1 (D) cells. Bar graphs show the percentage of BrdU-positive cells. *P < .05.

To elucidate the molecular linkage between estrogen/GPR30 signaling and claudin-1 induction, we used inhibitors of signaling pathways. As shown in Figures 4G and S7C, E2- and G1-induced upregulation of claudin-1 was inhibited by pretreatment with U0126 (ERK activation inhibitor) and LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor) but not by AG1478 (EGFR inhibitor), indicating that activation of ERK and/or Akt contributes to estrogen-induced claudin-1 upregulation (Figures 4G and S7C).

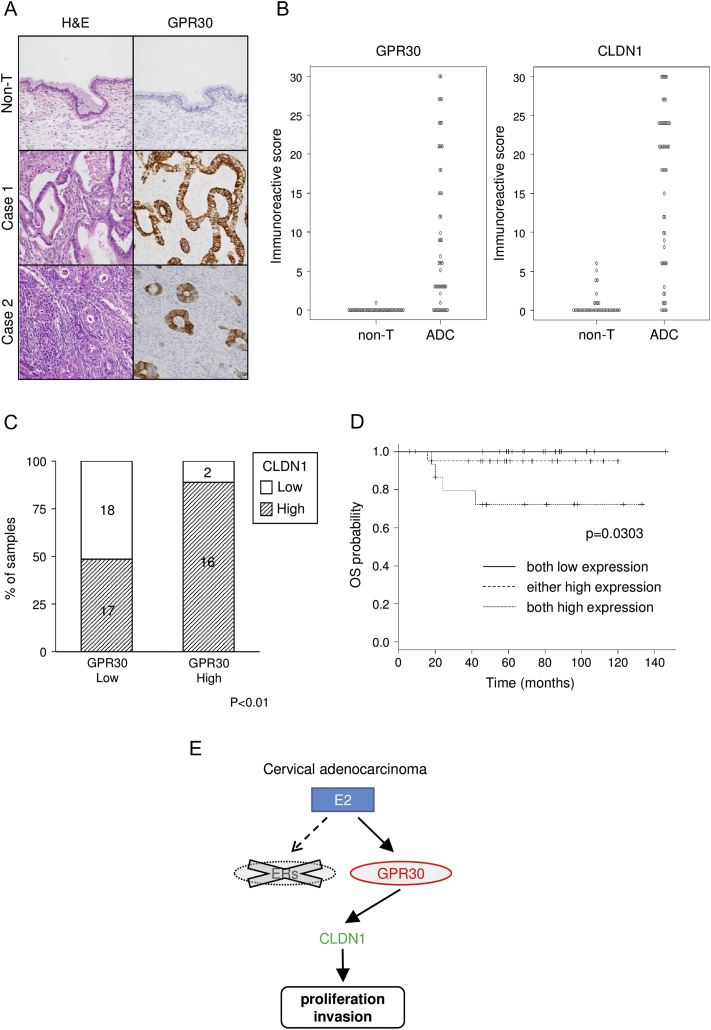

Co-Expression of GPR30 and Claudin-1 Correlates with Poor Prognosis in Surgical Specimens of Human Cervical Adenocarcinoma

Finally, we examined surgical specimens from cervical adenocarcinoma patients by immunohistochemistry using anti–claudin-1 and anti-GPR30 antibodies. As expected from the results in the cell lines, adenocarcinoma lesions in surgical specimens were strongly stained with anti-GPR30 antibody (Figure 6A) together with anti–claudin-1 antibody (Figure S1A). IRSs of GPR30 and claudin-1 were significantly higher in cervical adenocarcinomas than in normal endocervical glands in surgical specimens (Figure 6B). Furthermore, the percentage of cases with high claudin-1 expression was significantly higher in the high–GPR30 expression group (16/18, 89%) than in the low–GPR30 expression group (17/35, 49%, Figure 6C, P < .01), indicating a positive correlation between claudin-1 expression and GPR30 expression in cervical adenocarcinomas. Kaplan-Meier curve analysis revealed that patients with double high expression (both of claudin-1 and GPR30) had a significantly shorter overall survival than did patients with single high expression (either claudin-1 or GPR30) or patients with low expression of both molecules (P = .0303; Figure 6D). Multivariate analysis would have been helpful for evaluation here, but it was difficult to perform properly due to an insufficient number of events (<10).

Figure 6.

Positive correlation of overexpression of GPR30 and claudin-1 in surgical specimens of human cervical adenocarcinoma. (A) Immunohistochemistry of GPR30 in a surgical specimen of human cervical adenocarcinoma. GPR30 was strongly expressed in adenocarcinoma (cases 1 and 2), whereas it was undetectable in non-neoplastic glands (Non-T). (B) IRSs of GPR30 and CLDN1 were significantly higher in cervical adenocarcinoma (ADC, n = 53) than in normal endocervical glands (non-T, n = 44) in surgical specimens (P < .001). (C) Summary of the expression profile of CLDN1 and GPR30 in surgical specimens. The percentage of high CLDN1 expression cases was significantly higher in the high–GPR30 expression group than in the low–GPR30 expression group (P < .01). (D) Kaplan-Meier curve analysis. The group with double high expression of CLDN1 and GPR30 (both high expression) showed significantly shorter overall survival time (P = .0303). (C-D) The high-expression group has IRS of more than 10, and the low-expression group has IRS of 10 or less. (E) The illustration shows that GPR30, but not classical ERs, contributes to malignant potentials of cervical adenocarcinoma cells as a key receptor for estrogen (E2). CLDN1: claudin-1.

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that cervical adenocarcinoma cells can respond to estrogen stimulus via the membrane-bound estrogen receptor GPR30. This is the first study to provide evidence that GPR30 is the key receptor for estrogen signaling in cervical adenocarcinoma. The estrogen/GPR30 signaling upregulated tumor-promoting claudin-1 expression, and there was a positive correlation between GPR30 expression and claudin-1 expression in surgical specimens. Furthermore, patients with double high expression of claudin-1 and GPR30 had significantly shorter overall survival.

The sensitivity of the cells to estrogen was an unexpected result because cervical adenocarcinomas are generally believed to lose estrogen response on the basis of negative (or very weak) expression of classical nuclear ERs [7], [8], [9]. However, our results clearly demonstrated that all of the tested cervical adenocarcinoma cells were sensitive to estrogen stimulus at a physiological concentration together with high GPR30 expression and without classical nuclear ER (ERα) expression (Figure 3, A-C).

The existence of estrogen sensitivity and high GPR30 expression are very important to understand etiology of cervical adenocarcinoma. High level of serum estrogen may become a risk factor of cervical adenocarcinoma as reported for several cancers including breast, endometrial, ovarian, and gastric cancers [25], [26], [27], [28]. There is a growing body of evidence supporting that estrogenic GPR30 signaling is strongly associated with cancer proliferation, migration, invasion, metastasis, and prognosis [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. Our finding of GPR30 expression in cervical adenocarcinoma could connect estrogen and the disease progression. At least, we observed that a GPR30-specific agonist, G1, enhances proliferation of cervical adenocarcinoma cells (Figure 5). In addition, the side effects of hormonal therapy should be reexamined in the aspect of cervical adenocarcinoma development because treatment with tamoxifen, a hormone drug for breast cancer, is a well-known risk factor for endometrial cancers, and tamoxifen has been reported to act as a GPR30 agonist [30], [36], [37], [38].

Our result seems to imply that cervical epithelia switch their estrogen receptor subtype, from classical nuclear ERs to membrane-bound GPR30, during cancer development. This kind of subtype switch might enable the cells to respond rapidly to estrogen stimulus at the cell surface. We believe that detailed profiling of the receptor subtype in surgical specimens could provide a new insight into cervical adenocarcinoma, and this investigation is now in progress.

We found that estrogen/GPR30 signaling induces claudin-1 expression, a potential biomarker for cervical adenocarcinoma [13], via activation of ERK and/or Akt. We also observed that claudin-1 plays a pivotal role in proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumorigenesis of cervical adenocarcinoma cells, as previously reported in several tumors [39], [40], including breast cancer [15]. Considering these results, we hypothesize that estrogen/GPR30 signaling induces claudin-1 expression and contributes to cervical adenocarcinoma development and progression in vivo (Figure 6E). The positive correlation between claudin-1 expression and GPR30 expression in surgical specimens supports this idea. We also found that patients with double high expression of claudin-1 and GPR30 had significantly shorter overall survival. To gain a better understanding of cervical adenocarcinoma, the molecular mechanisms of the action of claudin-1 should be investigated in future studies. Our findings indicate the possibility of a new therapeutic strategy targeting cell surface molecules GPR30 and claudin-1 in cervical adenocarcinomas. In particular, hormonal therapy using GPR30-specific antagonists may have efficacy in cervical adenocarcinomas, like tamoxifen in ER-positive breast cancers. Of note, estrogen/GPR30 signaling has the potential to induce molecules other than CLDN1 in cervical adenocarcinoma as in the case of estrogen/ER signaling in other tumors [5]. It would be very interesting to explore other downstream molecules responsible for tumorigenesis of cervical adenocarcinoma. We will conduct further studies to analyze estrogen/GPR30 signaling in cervical adenocarcinoma.

Conclusion

Estrogen/GPR30 signaling could contribute to malignant potentials of cervical adenocarcinoma by induction of tumor-promoting claudin-1. Double high expression of GPR30 and claudin-1 predicts poor prognosis in cervical adenocarcinomas. Mechanism-based targeting of estrogen/GPR30 signaling and claudin-1 may be effective for cervical adenocarcinoma therapy.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

List of Antibodies.

List of Primers for RT-PCR.

Supplementary materials

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (JP16K08693 to N. S., JP16K21250 to T. Ao., JP17K08697 to M. O., JP26460421, and JP17K08698 to A. T.), Kurozumi Medical Foundation (A. T.), and grants-in-aid of Ono Cancer Research Fund (A. T.).

Authors' Contributions

The authors contributed in the following ways: T. Ak., K. T.: performed cell biological experiments and drafted the paper; A. T.: conceived the study, supervised all experiments, and performed the final revision of the manuscript; T. Ak., K. T.: designed and performed gene targeting experiments; T. Ao.: performed and analyzed immunocytochemistry and immunofluorescence; A. T., M. O., M. M.: performed and analyzed immunohistochemical experiments; T. S., N. S.: supervised experiments and helped with writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. The protocol for human study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient who participated in the investigation. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Committee at Sapporo Medical University (12-046_15-001).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Y. Kawami for technical assistance with the experiments.

References

- 1.Gien LT, Beauchmin MC, Thomas G. Adenocarcinoma: a unique cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Horst J, Siebers AG, Bulten J, Massuger LF, Kok IM. Increasing incidence of invasive and in situ cervical adenocarcinoma in the Netherlands during 2004-2013. Cancer Med. 2017;6(2):416–423. doi: 10.1002/cam4.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eifel PJ, Burke TW, Morris M, Smith TL. Adenocarcinoma as an independent risk factor for disease recurrence in patients with stage IB cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;59:38–44. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeuchi S. Biology and treatment of cervical adenocarcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016;28(2):254–262. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2016.02.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuffa LG, Lupi-Júnior LA, Costa AB, Amorim JP, Seiva FR. The role of sex hormones and steroid receptors on female reproductive cancers. Steroids. 2017;118:93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prossnitz ER, Barton M. Estrogen biology: new insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;389:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamoi S, AlJuboury MI, Akin MR, Silverberg SG. Immunohistochemical staining in the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas: another viewpoint. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21(3):217–223. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCluggage WG, Sumathi VP, McBride HA, Patterson A. A panel of immunohistochemical stains, including carcinoembryonic antigen, vimentin, and estrogen receptor, aids the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervival adenocaricnomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21:11–15. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkushi A, Irving J, Hsu F, Dupuis B, Liu CL, Rijn M, Gilks CB. Immunoprofile of cervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas using a tissue microarray. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:271–277. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0752-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwasniewska A, Postawski K, Gozdzicka-Jozefiak A, Kwasniewski W, Grywalska E, Zdunek M, Korobowicz E. Estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in HPV-positive and HPV-negative cervical carcinomas. Oncol Rep. 2011;26(1):153–160. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara H, Tortolero-Luna G, Mitchell MF, Koulos JP, Wright TC., Jr. Adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Expression and clinical significance of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Cancer. 1997;79(3):505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodner K, Laubichler P, Kimberger O, Czerwenka K, Zeillinger R, Bodner-Adler B. Oestrogen and progesterone receptor expression in patients with adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix and correlation with various clinicopathological parameters. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(4):1341–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akimoto T, Takasawa A, Murata M, Kojima Y, Takasawa K, Nojima M, Aoyama T, Hiratsuka Y, Ono Y, Tanaka S. Analysis of the expression and localization of tight junction transmembrane proteins, claudin-1, -4, -7, occludin and JAM-A, in human cervical adenocarcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2016;31:921–931. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawada N. Tight junction-related human diseases. Pathol Int. 2013;63:1–12. doi: 10.1111/pin.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou B, Moodie A, Blanchard AA, Leygue E, Myal Y. Claudin 1 in breast cancer: new insights. J Clin Med. 2015;4:1960–1976. doi: 10.3390/jcm4121952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayakawa O, Kudo R, Koizumi M, Yamauchi O, Yamamoto H, Takehara M. Establishment of a human adenocarcinoma cell line, CAC-1. Sapporo Med J. 1988;57:603–611. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng PS, Iwasaka T, Ouchida M, Fukuda K, Yokoyama M, Sugimori H. Growth suppression of a cervical cancer cell line (TMCC-1) by the human wild-type p53 gene. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:245–250. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghidoni I, Chlapanidas T, Bucco M, Crovato F, Marazzi M, Vigo D, Torre ML, Faustini M. Alginate cell encapsulation: new advances in reproduction and cartilage regenerative medicine. Cytotechnology. 2008;58(1):49–56. doi: 10.1007/s10616-008-9161-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takasawa A, Murata M, Takasawa K, Ono Y, Osanai M, Tanaka S, Nojima M, Kono T, Hirata K, Kojima T. Nuclear localization of tricellulin promotes the oncogenic property of pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33582. doi: 10.1038/srep33582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keira Y, Takasawa A, Murata M, Nojima M, Takasawa K, Ogino J, Higashiura Y, Sasaki A, Kimura Y, Mizuguchi T. An immunohistochemical marker panel including claudin-18, maspin, and p53 improves diagnostic accuracy of bile duct neoplasms in surgical and presurgical biopsy specimens. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:265–277. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naito Y, Hino K, Bono H, Ui-Tei K. CRISPRdirect: software for designing CRISPR/Cas guide RNA with reduced off-target sites. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1120–1123. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Frackelton AR, Jr, Bland KI. Estrogen action via the G protein–coupled receptor, GPR30: stimulation of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP-mediated attenuation of the epidermal growth factor receptor-to-MAPK signaling axis. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(1):70–84. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filardo EJ, Thomas P. Minireview: G protein–coupled estrogen receptor-1, GPER-1: its mechanism of action and role in female reproductive cancer, renal and vascular physiology. Endocrinology. 2012;153(7):2953–2962. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryu WS, Kim JH, Jang YJ, Park SS, Um JW, Park SH, Kim SJ, Mok YJ, Kim CS. Expression of estrogen receptors in gastric cancer and their clinical significance. Surg Oncol. 2012;106(4):456–461. doi: 10.1002/jso.23097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi JH, Do IG, Jang J, Kim ST, Kim KM, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Kang WK. Anti-tumor efficacy of fulvestrant in estrogen receptor positive gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7592. doi: 10.1038/srep07592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown SB, Hankinson SE. Endogenous estrogens and the risk of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers. Steroids. 2015;99(Pt A):8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mountzios G, Pectasides D, Bournakis E, Pectasides E, Bozas G, Dimopoulos MA, Papadimitriou CA. Developments in the systemic treatment of endometrial cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;79:278–292. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D, Hu L, Zhang G, Zhang L, Chen C. G protein–coupled receptor 30 in tumor development. Endocrine. 2010;38:29–37. doi: 10.1007/s12020-010-9363-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vivacqua A, Romeo E, Marco P, Francesco EM, Abonante S, Maggiolini M. The G protein–coupled receptor GPR30 mediates the proliferative effects induced by 17beta-estradiol and hydroxytamoxifen in endometrial cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(3):631–646. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albanito L, Madeo A, Lappano R, Vivacqua A, Rago V, Carpino A, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Musti AM, Andò S. G protein–coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) mediates gene expression changes and growth response to 17beta-estradiol and selective GPR30 ligand G-1 in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(4):1859–1866. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He YY, Cai B, Yang YX, Liu XL, Wan XP. Estrogenic G protein–coupled receptor 30 signaling is involved in regulation of endometrial carcinoma by promoting proliferation, invasion potential, and interleukin-6 secretion via the MEK/ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(6):1051–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandey DP, Lappano R, Albanito L, Madeo A, Maggiolini M, Picard D. Estrogenic GPR30 signalling induces proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells through CTGF. EMBO J. 2009;28(5):523–532. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marco P, Cirillo F, Vivacqua A, Malaguarnera R, Belfiore A, Maggiolini M. Novel aspects concerning the functional cross-talk between the insulin/IGF-I system and estrogen signaling in cancer cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015;6:30. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrie WK, Dennis MK, Hu C, Dai D, Arterburn JB, Smith HO, Hathaway HJ, Prossnitz ER. G protein–coupled estrogen receptor–selective ligands modulate endometrial tumor growth. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/472720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bissett D, Davis JA, George WD. Gynaecological monitoring during tamoxifen therapy. Lancet. 1994;344(8932):1244. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sismondi P, Biglia N, Volpi E, Giai M, Grandis T. Tamoxifen and endometrial cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;734:310–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vivacqua A, Romeo E, Marco P, Francesco EM, Abonante S, Maggiolini M. GPER mediates the Egr-1 expression induced by 17β-estradiol and 4-hydroxitamoxifen in breast and endometrial cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(3):1025–1035. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiozaki A, Shimizu H, Ichikawa D, Konishi H, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Iitaka D, Nakashima S. Claudin 1 mediates tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced cell migration in human gastric cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(47):17863–17876. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leotlela PD, Wade MS, Duray PH, Rhode MJ, Brown HF, Rosenthal DT, Dissanayake SK, Earley R, Indig FE, Nickoloff BJ. Claudin-1 overexpression in melanoma is regulated by PKC and contributes to melanoma cell motility. Oncogene. 2007;26:3846–3856. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of Antibodies.

List of Primers for RT-PCR.

Supplementary materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files.