Abstract

Many factors have been associated with venous thromboembolism. Among them, vitamin B12 deficiency can produce elevated homocysteine levels, which is a risk factor for venous embolism, since the latter interferes with the activation of Va coagulation factor by activation of C protein.

We present a case of a patient with metabolic syndrome with apparently unprovoked pulmonary embolism. After careful evaluation, megaloblastic anemia was detected. Even though the patient had biochemistry findings of hemolysis and blood smear did not showed fragmented erythrocytes, which is consistent with pseudo-microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism, Megaloblastic anemia, B12 deficiency

Introduction

Acute pulmonary embolism is a cardiovascular emergency. After initial stratification and directed treatment, etiology must be identified to decide anticoagulation time and to prevent future episodes. Many factors have been associated with venous thromboembolism. Among them, vitamin B12 deficiency can produce elevated homocysteine levels, which is a risk factor for venous embolism, since the latter interferes with the activation of Va coagulation factor by activation of C protein. This factor also increases the expression of tissue factor and suppresses sulfate heparin, an endogenous anticoagulant.

We present a 74-year-old patient with pulmonary embolism that was taken to thrombofragmentation and thrombolysis in situ. After careful analysis, it was considered that megaloblastic anemia and metabolic syndrome, as a state of hyperhomocysteinemia, was the cause of this particular event. Supplementary treatment with B12 was administrated with no further events. Vitamin B12 deficiency must be addressed and treated as a cause of acute pulmonary embolism.

Case report

A 74-year-old female with a background of metabolic syndrome was admitted to the emergency room with typical angina, dyspnea and syncope in 2 occasions. At admission, the blood pressure was normal (130/80 mmHg) as well as oxygen saturation (S02-92%), but the patient was tachycardic and tachypneic with heart rate of 110 bpm and respiratory rate of 24 rpm. Electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia, complete right bundle branch block, with ST segment elevation of 2 mm in the inferior wall; therefore, an emergency coronary angiography was performed, without coronary arteries lesions. Laboratory findings revealed increment of troponin I and NT-pro BNP, D-dimer was positive and data of megaloblastic anemia were detected. CT angiography confirmed a bilateral main, subsegmental acute pulmonary embolism (Fig. 1A and B) and dilatation of the right cavities (Fig. 1C). Echocardiogram reveled normal left ventricular systolic function with ejection fraction of 60%, right ventricular dilation with basal diameter of 46 mm, moderate pulmonary hypertension with systolic pulmonary artery of 60 mm Hg and right ventricular systolic dysfunction with the tricuspid annulus displacement during systole of 15 mm, right ventricular fractional shortening area of 25%, S tricuspid wave of 9.21 cm/seg, right ventricular and/or left ventricular ratio of 1.48 and shift of the interventricular septum to the left. Pulmonary thromboembolism was diagnosis with PESI score of 114 points and New York Heart Association functional class IV; therefore low molecular-weight heparin was administrated.

Fig. 1.

A,B- CT angiography showing thrombus (Black arrows) in the main, and subsegmental branches of the pumonary artery. Ao, Aorta; LA, left ventricle; PA, pumonary artery; RA, right atrium, RV, right ventricle.

Right catheterization revealed systolic and/or diastolic and/or mean pulmonary artery pressure of 60/18/35 mm Hg, respectively, right ventricular systolic and diastolic pressure of 60/4 mm Hg, respectively, end-diastolic right ventricular pressure of 12 mm Hg, right atrial a wave of 10 mm Hg, v wave of 12 mmHg and mean pressure of 11 mmHg.

Two days later she developed cardiogenic shock, which was treated with norepinephrine and dobutamine. Once stabilized, she underwent bilateral thrombofragmentation, pulmonary thrombolysis in situ with alteplase (10 mg left ap and 5 mg right ap) (Fig. 2) and vena cava filter placement was performed without complications. Post procedure the systolic and/or diastolic and/or mean pulmonary pressure was of 55/18/30 mmHg, respectively.

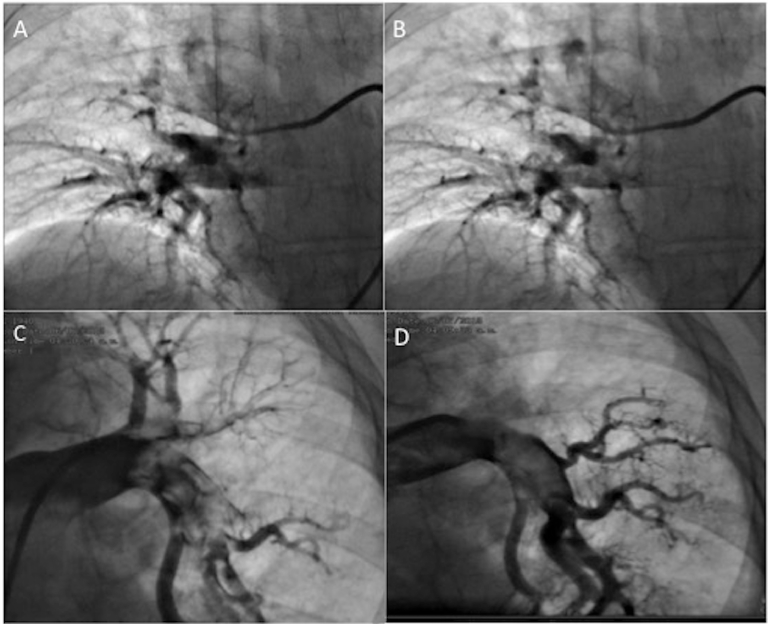

Fig. 2.

Right catheterization before (A) and after (B) thrombus fragmentation of the right pulmonary artery and before (C) and after (E) thrombus fragmentation of the left pumonary artery thrombus fragmentation with Guider Softip XF (8FR.).

Provoked causes of venous thromboembolism were dismissed. Infectious diseases and hereditary thrombophilia was ruled out. She was discharged with vitamin k antagonist. Megaloblastic anemia was confirmed with multisegmented neutrophils in blood smear. Aspirate of bone marrow was negative for malignancy. B12 levels were measured, and were found below reference values (20 ng/l). Endoscopy and colonoscopy were normal, atrophic gastritis was ruled out. It was determined that the cause of pulmonary embolism was megaloblastic anemia since there were no other identifiable causes. After 2 years of follow-up, she remains without new episodes of venous embolism. She developed an iron deficiency anemia, and is being replaced with iron, B12 and folic acid (Table 1).

Table 1.

Behavior of the parameters of blood biometry before, during, and after vitamin B12 treatment.

| Parameters | Admission | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 8 | Day 9 | Day 20* | Day 30 | Day 40 | year 1 | year 2 | year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 10 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 7.8 | 10.1 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 13.6 | 11.7 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 30.7 | 28.4 | 28.6 | 27.7 | 26.2 | 24.9 | 32.1 | 36.7 | 33.7 | 41.6 | 37.6 |

| MCV (80–97 fL) | 94.5 | 95.9 | 96.6 | 99.3 | 99.6 | 100.8 | 94.7 | 91.2 | 70.7 | 85.6 | 76.6 |

| MCH (27–31 pg) | 30.8 | 30.7 | 31.1 | 32.6 | 32.7 | 31.6 | 29.8 | 27.3 | 33.7 | 27.9 | 23.8 |

| Reticulocytes (0.5%–1.55 %) | . | . | . | 2 | . | 2.6 | . | . | . | 3 | 3.23 |

* Start of treatment with hydroxocobalamin.

MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCV, Mean corpuscular volume.

Discussion

A first event of unprovoked pulmonary embolism should raise the suspicion of B12 deficiency in the presence of megaloblastic anemia. B12 deficiency has 2 important components that are usually unrecognized: the prothrombotic potencial and the ability to simulate a microangiophatic hemolytic anemia. B12 deficiency is generally underdiagnosed and undertreated. It increases homocysteine plasma levels, a highly known risk factor for venous embolism. Homocysteine interferes with activation of factor Va, by increasing levels of protein C, apart from increasing the expression of tisular factor and suppressing sulfate heparin, an endogenous anticoagulant [1], [2], [3].

Although our patient had biochemical findings of hemolysis, peripheral smear did not show typical fragmented erythrocytes, which can relate to the term pseudo-microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. According to the literature, it can be easily treated if diagnosed promptly. The most common cause of B12 deficiency is pernicious anemia, but in this case was ruled out, considering probably other factors related to its deficiency [1], [4], [5], [6].

The association of hyperhomocysteinemia and venous thromboembolism is controversial, there are many innate and acquired factors that can promote thrombosis in this patient's context, and although the duration of anticoagulant is unclear, it has been mentioned that supplementation with vitamin B12 can lower these levels and prevent recurrent thrombotic events. Our patient has multiple metabolic manifestations and involvement of glands, manifested with hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, and megaloblastic anemia, however due to clinical and laboratory characteristics does not meet criteria of polyglandular syndrome.

It is well-known that hyperhomocysteine is related to cardiovascular events, renal diseases, and retinopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus caused by excessive oxidative stress. Metabolic syndrome is the epitome of endothelial dysfunction. Our patient has among the acquired risk factors for hyperhomocysteinemia, vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, sedentary lifestyle, the use of metformin, and the postmenopausal state which increase the risk for high levels of homocysteine [2], [3], [7], [8], [9].

Even though the duration of anticoagulation therapy is unknown, supplementary B12 helps diminishing the event rate of recurrent thrombosis.

Conclusion

B12 deficiency should be systematically considered as a potential cause of thrombotic events, especially in the context of a patient with risk factors for endothelial dysfunction. Homocysteine levels are not useful in follow-up, but can help to guide the therapy in an individualized way.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2018.07.018.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Oliveira LRDe, Fonseca JR. Hematology, transfusion and cell therapy simultaneous pulmonary thromboembolism and superior mesenteric venous thrombosis associated with hyperhomocysteinemia secondary to pernicious anemia-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2018;40(1):79–81. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2017.11.004. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaas AK, Ambinder D, Moliterno A, Streiff M, Clark BW. Pernicious Emboli : an uncommon cause of a common problem. Am J Med [Internet]. 129(2):e9–11. Available from: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Üzmezoğlu B, Özdemir L, Hatipoğlu ON, Özdemir B, Edis EÇ. A case of massive pulmonary embolism due to diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperhomocysteinemia. Eurasian J Pulmonol. 2014;16:124–126. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shu X, Li Z, Chang Y, Liu S, Wang W. Effects of folic acid combined with vitamin B12 on DVT in patients with homocysteine cerebral infarction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:2538–2544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhary A, Desai U, Joshi JM. Venous thromboembolism due to hyperhomocysteinaemia and tuberculosis. Clin Case Report. 2017;30:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melhem A, Desai A, Hofmann MA. Acute myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism in a young man with pernicious anemia-induced severe hyperhomocysteinemia. Thromb J. 2009;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-7-5. 2009;5:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichinger S. Are B vitamins a risk factor for venous thromboembolism ? Yes. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:307–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pin L, Martı J, Garcı X. Vitamin B12 deficiency, hyperhomocysteinemia and thrombosis : a case and control study. Int J Hematol. 2011;93:458–464. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0825-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lentz SR. Mechanisms of homocysteine-induced atherothrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1646–1654. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.