Abstract

Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) with ST8/SCCmecIV threatens human health. However, its pathogenesis remains unclear. ST8 CA-MRSA (CA-MRSA/J) with SCCmecIVl, which carries the large LPXTG-motif–containing putative adhesin gene, spj, has emerged in Japan. We present the first reported case of death from CA-MRSA/J. The patient was a 64-year-old woman with iliopsoas abscesses complicated by septic pulmonary embolism and multiorgan abscesses. Vancomycin, arbekacin, daptomycin and rifampicin were ineffective. CA-MRSA/J was resistant to erythromycin, clindamycin and antiseptics and was invasive in a HEp-2 cell assay, in contrast to skin-derived villous-adherent CA-MRSA/J. This suggests the strongly invasive pathotype of CA-MRSA/J.

Keywords: Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, iliopsoas abscess, pathotype, septic pulmonary embolism, ST8/SCCmecIVl

Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which is also known as healthcare-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA), is a common antimicrobial-resistant pathogen [1], [2]. Another type of MRSA, community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA), emerged in the United States in 1997 to 1999 [1], [2], [3] and is associated with severe infections in children in the community. It is characterized by the genotype ST1/SCCmecIVa, Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) genes and lower multidrug resistance than HA-MRSA. Global examples of CA-MRSA include the genotypes ST8/SCCmecIV (particularly USA300, which has caused serious outbreaks [1], [2], [4], [5], [6]), ST30/SCCmecIV, ST59/SCCmecV [7] and ST80/SCCmecIV (particularly in Europe [8]). Although SCCmecIV (like SCCmecV) is common among CA-MRSA strains [2], its role in the pathogenesis of MRSA remains unclear.

CA-MRSA is usually associated with skin and soft tissue infections, but also with invasive infections [1], [2]. The expression of cytolytic peptides, such as phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs), is up-regulated in CA-MRSA, which often produces PVL [2], [4].

We reported a CA-MRSA with a novel genotype, ST8/spa606(t1767)/SCCmecIVl (CA-MRSA/J), in Japan in 2012 [9], [10]. CA-MRSA/J is characterized by the LPXTG-motif–containing large protein (putative adhesin) gene, spj, in SCCmecIVl [9], [10], which was first isolated in Niigata, Japan, in 2003 as ST8/SCCmecIVx (unknown subtype IV) and was associated with bullous impetigo in children [11]. CA-MRSA/J induces a broad range of diseases in various age groups, including skin and soft tissue infections, invasive infections and diarrhoea [10], [11]. It has spread widely in Japan, including by public transport [12], and has been transmitted internationally to Hong Kong [10].

In the present study, we present the first reported case of a death from CA-MRSA/J infection in Japan, which supports the elevated virulence of this pathogen. We also report its rapid invasion of HEp-2 cells in vitro and the detection of spj.

Case report

A 64-year-old woman was admitted in 2012 (day 1) with a disturbance of consciousness and paralysis of the left upper and lower limbs, which had developed 1 day before her admission (day −1). The severity of her low back pain and sciatica had increased from day −10. At admission, her white blood cell count and C-reactive protein levels were 16 600/μL (normal range, 3000–9000/μL) and 39.4 mg/dL (normal range, 0.0–0.5 mg/dL), respectively. Computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral multiple iliopsoas abscesses (IPAs) (Fig. 1(a-1) and (a-2)) and pyogenic discitis (Fig. 1(a-3)). A diagnosis of septic shock due to iliopsoas abscess was made, and vancomycin (1 g per day) and meropenem (1 g per day) were administered intravenously, according to Japanese guidelines [13], to avert possible infection with methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci, enterobacteria, or anaerobes. CT-guided drainage was performed on day 2. An MRSA (strain SI1) was cultured from the blood and IPAs on day 4. Vancomycin was increased to 1.5 g per day. Arbekacin, an anti-MRSA agent (175 mg per day), was administered intravenously to avert possible infection by vancomycin-resistant MRSA. However, the patient's general condition (vital signs and organ failure) deteriorated, so vancomycin was changed to daptomycin (400 mg per day), administered intravenously on day 5. A lung lesion detected with CT on day 4 was shown not to be caused directly by a bacterial pathogen but was attributed to ventilator-associated pneumonia and pulmonary oedema. CT-guided abscess drainage was performed again. A CT scan on day 5 revealed multiple large bilateral IPAs (Fig. 1(b-1) and (b-2)) and a septic pulmonary embolism (Fig. 1(b-3)). The patient's condition deteriorated further, so oral rifampicin (600 mg per day) was added to the patient's regimen on day 6 to avert any possible contamination of the device. The sepsis in the patient was too severe to be controlled. On day 8, her white blood cell count and C-reactive protein levels were 25 800/μL and 15.6 mg/dL, respectively, and she died on day 9. Abscesses in the heart apex (Fig. 1(c)), right lung (Fig. 1(d)) and bone marrow (Fig. 1(e)) as well as SI1 bacterial aggregates in the lung blood vessels (Supplementary Fig. S1) were detected at pathologic examination. Multiorgan thromboembolism was also severe, and shock liver and shock kidney were observed. SI1 met the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for the definition of CA-MRSA [1]. The ethics review board of Shimane Prefectural Central Hospital, Shimane, Japan, specifically approved this study (R16-057).

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan (a, b) and pathologic anatomy (c–e) of patient on admission days 1 (a), 5 (b) and 9 (c–e). (a-1), (a-3) and (b-1) show coronal view on CT; (a-2), (b-2) and (b-3) show axial view on CT. Arrows in (a-1) and (a-2) indicate bilateral multiple iliopsoas abscesses (IPAs), shown as low-density areas. Arrows in (b-1) and (b-2) indicate enlarged IPAs. Arrows in (a-3) indicate pyogenic discitis; L3–L4 and L4–L5 intervertebral discs are swollen. Arrowheads in (b-3) indicate septic pulmonary embolism, apparent as multiple foci of consolidation in bilateral lung lobes. (c-1) to (c-3) show heart apex abscesses; marked neutrophil infiltration was noted in epicardial adipose tissue over heart muscle layer (areas enclosed by circle). (d-1) and (d-2) show right lung abscesses (areas enclosed by circle). (e) Abscesses in bone marrow; intramedullary abscesses enclosed by circle.

Characterization of microbe

MRSA typing, including the sequence type (ST), the clonal complex (CC), the spa type, the agr type, the SCCmec type [14] and the coagulase (Coa) type and a pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis were performed as described previously [14], [15], [16]. A PCR analysis of 50 virulence genes included three leukocidin genes (lukPVSF, lukE-lukD and lukM), five haemolysin genes (hla, hlb, hlg, hlg-v and hld), the peptide cytolysin (PSMα) gene (psmα), 19 staphylococcal superantigen (SAg) genes, designated enterotoxin or enterotoxin-like genes (tst, sea-e, seg-j, selk-r and selu), the staphylococcal exotoxin (set) genes, staphylococcal superantigen-like gene cluster (ssl), three exfoliative toxin genes (eta, etb and etd), the epidermal cell differentiation inhibitor gene (edin or ednA), 14 adhesin genes (icaA/D, eno, fib, fnbA/B, ebpS, clfA/B, sdrC-E, cna and bbp), a putative adhesin gene (spj) and the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) gene arcA [10], [15], [16], [17]. Susceptibility testing of the bacterial strain was performed with the agar dilution method on Müller-Hinton agar according to previously described procedures [18], [19]. Thirty antimicrobial and related agents were tested, including four β-lactams, three aminoglycosides, three tetracyclines, two macrolides/lyncosamides, two fluoroquinolones and two glycopeptides; linezolid, daptomycin, rifampicin, trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole, fosfomycin, mupirocin and fusidic acid; and six antiseptics and related agents (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Breakpoints for drug resistance were those described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [14]. Resistance genes mecA, aadD, aacA-aphD, ermA, ermB, ermC, msrA, msrB, qacA and qacB were examined with PCR (Supplementary Table S3 [18], [20], [21], [22]). The messenger RNA expression of the PSMα gene (psmα) was examined with a reverse-transcriptase PCR assay [15]. A plasmid was transferred by filter mating, and plasmid DNA was analysed as described previously [15], [18]. The bacterial infection of HEp-2 cells was assessed by scanning and transmission electron microscopy [23]. Data were analysed statistically with Student's t test and Fisher's exact test. The level of significance was defined as p < 0.05.

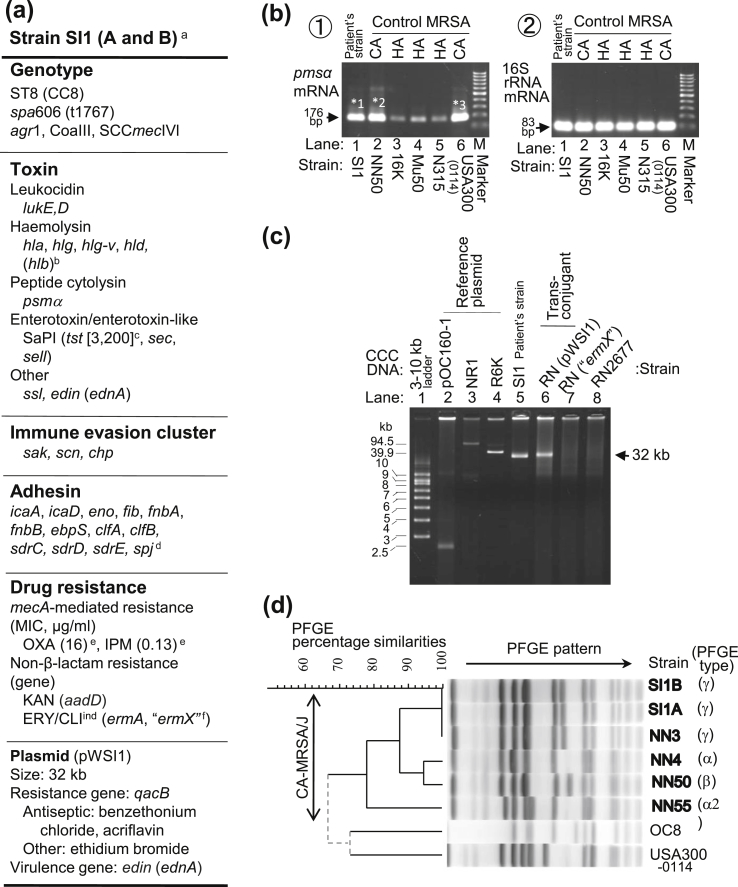

SI1 has the typical genotype of CA-MRSA/J (Fig. 2(a)) [9], [10], [15], [16], [24], [25], including strong psmα expression (Fig. 2(b)). It is susceptible to generally recommended anti-MRSA agents (Supplementary Table S1). SI1 exhibits resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin which is encoded by two genes, nontransmissible ermA (located on the chromosome) and transmissible ‘ermX’ (which is negative for ermA, ermB, ermC, msrA and msrB); ‘ermX’ confers erythromycin and clindamycin resistance on its host (S. aureus RN2677) and is not plasmid associated (Fig. 2(a) and (c); Supplementary Table S2). SI1 has a 32 kb transmissible plasmid (pWSI1) (Fig. 2(c)) carrying qacB, which confers antiseptic and ethidium bromide resistance (Fig. 2(a) and (c), Supplementary Table S2), and edin (ednA), which encodes epidermal cell differentiation inhibitor A (Fig. 2(a)). pWSI1 was transferred from SI1 to S. aureus RN2677 by filter mating and selection with ethidium bromide and the transconjugants obtained, S. aureus RN2677 carrying pWSI1, were positive for edin (ednA) in a PCR assay, similar to SI1. SI1 and CA-MRSA/J strain NN3 (from bullous impetigo [10], [11]) share very similar PFGE patterns (PFGE type γ; Fig. 2(d)) [10], [25].

Fig. 2.

Molecular characteristics of MRSA strain SI1. (a) SI1A and SI1B (marked with ‘a’), isolated from blood and IPA pus of patient, respectively, displayed same characteristics. They carries split β-haemolysin gene (hlb, marked with ‘b’) arising from insertion of phage 3 [15], which carries immune evasion cluster (sak, scn and chp); expressed toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (tst product) (ng/mL; as marked with ‘c’); carried putative adhesin gene spj[9], [10] (marked with ‘d’) and displayed low minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for oxacillin (OXA) and imipenem (IPM) (marked with ‘e’), consistent with characteristics of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) [24]. KAN, kanamycin; ERY, erythromycin; CLI, clindamycin; ind, inducible. (b) psmα expression level of SI1 (*1), normalized to 16S rRNA expression, was significantly higher than that of HA-MRSA (ST239/SCCmecIII strain 16K, ST5/SCCmecII strains Mu50 and N315) (p < 0.01), similar to those of CA-MRSA/J strain NN50 (*2) and USA300 (*3). (c) Covalently closed circular (CCC) plasmid DNA was analysed with agarose gel electrophoresis. RN (pWSI1), S. aureus RN2677 carrying pWSI1; RN (ermX), RN2677 carrying ermX. (d) SI1A and SI1B shared same pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) pattern. Strains NN3, NN4, NN50 and NN55 are PFGE type strains of CA-MRSA/J [10], [25]; USA300-0114 is USA300 (ST8/SCCmecIVa) type strain; OC8, Russian CA-MRSA ST8/SCCmecIVe strain, which has 1 Mbp (megabase) genomic inversion [16].

Individual cells of SI1 adhered to the HEp-2 cell surface (Fig. 3(a-1)), interacting tightly with the membrane (Fig. 3(b-1)) and ultimately invaded the cytoplasm of HEp-2 cells (Fig. 3(c-1)). However, aggregated NN3 bacteria adhered to the HEp-2 cell surfaces (Fig. 3(a-2) and (b-2)) and remained attached to the microvilli above the cell surface (Fig. 3(c-2)).

Fig. 3.

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs (SEM and TEM) showing adherence to and invasion to HEp-2 cells by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA)/J strains SI1 and NN3 after incubation for 1 hour. Electron micrographs: (a) and (b), SEM; (c), TEM. CA-MRSA/J strain: (a-1), (b-1) and (c-1), SI1 (isolated from fatal IPA complicated with septic pulmonary embolism and multiorgan abscesses); (a-2), (b-2) and (c-2), NN3 (isolated from bullous impetigo). Arrows in (a) and (b) indicate bacterial adherence. SI1 adherence was characterized by tight interaction with HEp-2 membrane (wrapped by elongated HEp-2 cell membrane), whereas NN3 adherence was characterized by induction of microvillus elongation (arrowhead) and appearance as microcolony (bacterial aggregates). Percentages of membrane-wrapped MRSA were 78.0% (39/50) for SI1 and 4.0% (2/50) for NN3 (p < 0.01). In (c-1), most SI1 cells were wrapped by elongated HEp-2 cell membrane (right arrow) or invaded cytoplasm of HEp-2 cells (left arrow). In (c-2), NN3 (arrow) attached to elongated microvilli (arrowhead). percentages of HEp-2 cell-invaded MRSA were 47.5% (28/59) for SI1 and 2.6% (1/39) for NN3 (p < 0.01).

Discussion

IPA is an uncommon infection. However, cases of IPA attributable to MRSA have been increasing in the United States since 2005 [26], and serious USA300 outbreaks have occurred [1], [2], [4], [5], [6]. The unique clinical features of the present case of IPA were its rapid progression to septic pulmonary embolism and abscesses in the heart apex, right lung and bone marrow, with multiorgan thromboembolism, suggesting the strong invasive pathotype of SI1. There are two types of IPA, primary and secondary [26], [27]. Because pustular eruptions were present on the patient's skin, which were possibly the initial SI1 infection, we ascribed her IPA primarily to haematogenous spread [26], [27]. Interestingly, a large mass of SI1 aggregates had accumulated in all the lung blood vessels, possibly triggering septic pulmonary embolism.

SI1 belongs to CA-MRSA/J PFGE type γ (representative strain, NN3 [10]). However, in an in vitro infection model, NN3 attached to the elongated microvilli of HEp-2 cells, whereas SI1 rapidly invaded the HEp-2 cells, confirming the strongly invasive potential of SI1. A unique feature of CA-MRSA/J is its LPXTG-motif–containing putative adhesin Spj, encoded by spj [9], [10]. Therefore, the strongly invasive pathotype (high virulence) of SI1 and the skin-infection pathotype (low virulence) of NN3, observed both in vivo and in vitro, appear to have been created by Spj in two ways, invasion (SI1) or surface adherence (NN3).

The spj gene is a key feature defining the new SCCmecIV subtype (IVl) and therefore the emergent lineage ST8/spa606(t1767)/SCCmecIVl (CA-MRSA/J) [9], [10]. Spj is a large (∼1600 aa) surface protein [9] with a variable number of hydrophilic 22 aa repeats (Wan et al., unpublished data). Spj probably consists of region A, containing a 22 aa variable region (target/ligand-binding region), region B (‘stalk’ region, which allows the presentation of region A at the bacterial surface for ligand interaction), region W (wall-anchored and wall-spanning region containing the LPXTG motif) and region M (membrane-spanning region) [9] and is covalently linked to the peptidoglycan cell wall, extending towards the environment. Spj shows no amino acid sequence similarities to previously published cell-wall–anchored surface proteins [28].

Li et al. [29] reported the rapid colonization and its virulence determinant, susX, of ST239/SCCmecIII HA-MRSA in 2012. susX is located on a prophage, φSPβ-like. The susX gene product, SusX, also contains the LPXTG motif. However, spj diverges from susX in its size (4815 bp [9] vs. 615 bp [29], respectively) and nucleotide and amino acid sequences (with no significant homologies), suggesting that the two have distinct functions.

Divergent lineages of CA-MRSA dominate different regions of the world, although USA300 is the most successful clone worldwide [1], [2], [4], [5], [6]. Other examples include those from livestock, food production chains and farm-related humans in Europe (such as spat127) [30]; USA500 (CC8) from CA and HA infections in the United States [31]; and ST8/spat008/SCCmecIVe, which often displays levofloxacin resistance and a 1 Mbp genomic inversion in Russia [15], [16], [32]. CA-MRSA/J has its own unique features: SCCmecIVl with spj (described above) and the phage-related chromosomal island SaPI (SAPIj50) carrying a tst region, which may have originated from SaPIm1/n1 of the ST5/SCCmecII HA-MRSA New York/Japan clone [10]. Although SI1 is negative for PVL and ACME, which are key features of USA300 [4], Spj and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1, encoded by tst) may confer a selective advantage on CA-MRSA/J.

SI1 is resistant to erythromycin and clindamycin (inducible type) and carries a transmissible plasmid carrying qacB and edin (ednA), similar to some CA-MRSA/J strains [10], [11].

In conclusion, we have presented the first reported case of death from CA-MRSA/J infection in Japan, which was characterized by IPA that rapidly progressed to septic pulmonary embolism and multiorgan abscesses. This death supports the strongly invasive pathotype (high virulence) of SI1, as well as its capacity to invade HEp-2 cells in vitro and the detection of spj.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by each institutional sources, including personal (TY) money obtained from lectures at universities and colleges. We thank L. K. McDougal and L. L. McDonald for the USA300 type strain; K. Hiramatsu for ST5/SCCmecII reference strains; H. Moro for kind discussion; and W. Higuchi and Y. Iwao for technical information.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2018.08.004.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

figs1.

References

- 1.Klevens R.M., Morrison M.A., Nadle J., Petit S., Gershman K., Ray S. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otto M. Community-associated MRSA: what makes them special? Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Four pediatric deaths from community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Minnesota and North Dakota, 1997–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:707–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diep B.A., Gill S.R., Chang R.F., Phan T.H., Chen J.H., Davidson M.G. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367:731–739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauß L., Stegger M., Akpaka P.E., Alabi A., Breurec S., Coombs G. Origin, evolution, and global transmission of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus ST8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E10596–E10604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702472114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Planet P.J. Life after USA300: the rise and fall of a superbug. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(Suppl. 1):S71–S77. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung W.C., Wan T.W., Kuo Y.C., Yamamoto T., Tsai J.C., Lin Y.T. Molecular evolutionary pathways toward two successful community-associated but multidrug-resistant ST59 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages in Taiwan: dynamic modes of mobile genetic element salvages. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fluit A.C., Carpaij N., Majoor E.A., Weinstein R.A., Aroutcheva A., Rice T.W. Comparison of an ST80 MRSA strain from the USA with European ST80 strains. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:664–669. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwao Y., Takano T., Higuchi W., Yamamoto T. A new staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec IV encoding a novel cell-wall–anchored surface protein in a major ST8 community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18:96–104. doi: 10.1007/s10156-011-0348-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwao Y., Ishii R., Tomita Y., Shibuya Y., Takano T., Hung W.C. The emerging ST8 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in the community in Japan: associated infections, genetic diversity, and comparative genomics. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18:228–240. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takizawa Y., Taneike I., Nakagawa S., Oishi T., Nitahara Y., Iwakura N. A Panton-Valentine leucocidin (PVL)-positive community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain, another such strain carrying a multiple-drug resistance plasmid, and other more-typical PVL-negative MRSA strains found in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3356–3363. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3356-3363.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwao Y., Yabe S., Takano T., Higuchi W., Nishiyama A., Yamamoto T. Isolation and molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from public transport. Microbiol Immunol. 2011:1348–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2011.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Japanese Society of Nephrology and Pharmacotherapy. [Drug dosages requiring the most precautions for reduced renal function]. Available at: https://www.jsnp.org/ckd/yakuzaitoyoryo.php.

- 14.International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Elements (IWG-SCC) Classification of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec): guidelines for reporting novel SCCmec elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4961–4967. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00579-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khokhlova O.E., Hung W.C., Wan T.W., Iwao Y., Takano T., Higuchi W. Healthcare- and community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and fatal pneumonia with pediatric deaths in Krasnoyarsk, Siberian Russia: unique MRSA’s multiple virulence factors, genome, and stepwise evolution. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan T.W., Khokhlova O.E., Iwao Y., Higuchi W., Hung W.C., Reva I.V. Complete circular genome sequence of successful ST8/SCCmecIV community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (OC8) in Russia: one-megabase genomic inversion, IS256’s spread, and evolution of Russia ST8-IV. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takano T., Higuchi W., Zaraket H., Otsuka T., Baranovich T., Enany S. Novel characteristics of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains belonging to multilocus sequence type 59 in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:837–845. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto T., Tamura Y., Yokota T. Antiseptic and antibiotic resistance plasmid in Staphylococcus aureus that possesses ability to confer chlorhexidine and acrinol resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:932–935. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.6.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne PA: 2015. Performance standard for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 25th informational supplement M100-S25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutcliffe J., Grebe T., Tait-Kamradt A., Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lina G., Quaglia A., Reverdy M.E., Leclercq R., Vandenesch F., Etienne J. Distribution of genes encoding resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins among staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1062–1066. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noguchi N., Suwa J., Narui K., Sasatsu M., Ito T., Hiramatsu K. Susceptibilities to antiseptic agents and distribution of antiseptic-resistance genes qacA/B and smr of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Asia during 1998 and 1999. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:557–565. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto T., Kaneko M., Changchawalit S., Serichantalergs O., Ijuin S., Echeverria P. Actin accumulation associated with clustered and localized adherence in Escherichia coli isolated from patients with diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2917–2929. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2917-2929.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takano T., Higuchi W., Yamamoto T. Superior in vitro activity of carbapenems over anti–methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and some related antimicrobial agents for community-acquired MRSA but not for hospital-acquired MRSA. J Infect Chemother. 2009;15:54–57. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0665-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung W.C., Mori H., Tsuji S., Iwao Y., Takano T., Nishiyama A. Virulence gene and expression analysis of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus causing iliopsoas abscess and discitis with thrombocytopenia. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:1004–1008. doi: 10.1007/s10156-013-0561-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alonso C.D., Barclay S., Tao X., Auwaerter P.G. Increasing incidence of iliopsoas abscesses with MRSA as a predominant pathogen. J Infect. 2011;63:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallick I.H., Thoufeeq M.H., Rajendran T.P. Iliopsoas abscesses. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:459–462. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.017665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dedent A.C., Marraffini L.A., Schneewind O. Staphylococcal sortase and surface proteins. In: Fischetti V.A., Novick R.P., Fischetti J.J., Potnoy D.A., Rood J.I., editors. Gram-positive pathogens. 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 486–495. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M., Du X., Villaruz A.E., Diep B.A., Wang D., Song Y. MRSA epidemic linked to a quickly spreading colonization and virulence determinant. Nat Med. 2012;18:816–819. doi: 10.1038/nm.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macori G., Giacinti G., Bellio A., Gallina S., Bianchi D.M., Sagrafoli D. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in the ovine dairy chain and in farm-related humans. Toxins. 2017;9:161. doi: 10.3390/toxins9050161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frisch M.B., Castillo-Ramírez S., Petit R.A., Farley M.M., Ray S.M., Albrecht V.S. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA500 strains from the US emerging infections program constitute three geographically distinct lineages. mSphere. 2018;3 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00571-17. e00571-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gostev V., Kalinogorskaya O., Kruglov A., Lobzin Y., Sidorenko S. Characterisation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to ceftaroline collected in Russia during 2010–2014. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;12:21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.