Abstract

MLL-fusion proteins, AF9 and ENL, play an essential role in the recruitment of DOT1L and the H3K79 hypermethylation of MLL target genes, which is pivotal for leukemogenesis. Blocking these interactions may represent a novel therapeutic approach for MLL-rearranged leukemia. Based on the 7 mer DOT1L peptide, a class of peptidomimetics was designed. Compound 21 with modified middle residues, achieved significantly improved binding affinities to AF9 and ENL, with KD values of 15 nM and 57 nM, respectively. Importantly, 21 recognizes and binds to the cellular AF9 protein and effectively inhibits the AF9-DOT1L interactions in cells. Modifications of the N- and C-termini of 21 resulted in 28 with 2-fold improved binding affinity to AF9 and much decreased peptidic characteristics. Our study provides a proof-of-concept for development of nonpeptidic compounds to inhibit DOT1L activity by targeting its recruitment and the interactions between DOT1L and MLL-oncofusion proteins AF9 and ENL.

Keywords: MLL fusion proteins, DOT1L, peptidomimetics, protein−protein interactions

Translocation of the mixed lineage leukemia gene (MLL1) is one of the most common chromosome rearrangements found in leukemia patients.1 To date more than 70 genes have been reported to fuse with MLL1.2 Among MLL fusion proteins, MLL-AF4, MLL-AF9, MLL-AF10, and MLL-ENL account for more than 80% of MLL leukemias.3 AF9 and ENL are closely related members of the YEATS domain protein family and have been identified as part of several reported complexes known as Super Elongation Complex (SEC), AEP (AF4, ENL, P-TEFb), and DotCom Complex.4−6 They share high homology in their C-terminal hydrophobic domain known as ANC1 Homology Domain (AHD) that is responsible for the recruitment of several multiprotein complexes.5 Through these protein–protein interactions (PPIs) AF9 and ENL recruit both gene repressive complexes through CXB8 and BCoR as well as gene activating complexes through AF4 and DOT1L.7−9 Both AF4 and DOT1L share a conserved AF9/ENL binding domain that interacts with the same AHD domain of AF9 and ENL in a mutually exclusive manner.5,10,11 One of the molecular mechanisms of leukemogenesis is mediated by the recruitment of the histone methyltransferase DOT1L, Disruptor of Telomeric silencing 1-like, by MLL-AF9/ENL, to MLL1 target genes, such as HOXA9 and MEIS1. The recruitment of DOT1L results in hypermethylation of H3K79 at the HOXA9 and MEIS1 loci and sustained expression of these genes, which is pivotal for leukemogenesis induced by these MLL oncogenic fusion proteins.12−14 DOT1L is a validated therapeutic target for MLL-rearranged leukemia, and a small molecule, SAM competitive DOT1L inhibitor, EPZ-5676, has entered phase I clinical trials.15 However, several groups, using conditional Dot1l-knockout mouse models, have demonstrated that Dot1l plays an important role in maintaining normal adult hematopoiesis,16,17 which raises the possibility of side effects by direct targeting of the catalytic domain. Therefore, investigating and developing alternative strategies for inhibiting DOT1L activity is important and necessary.

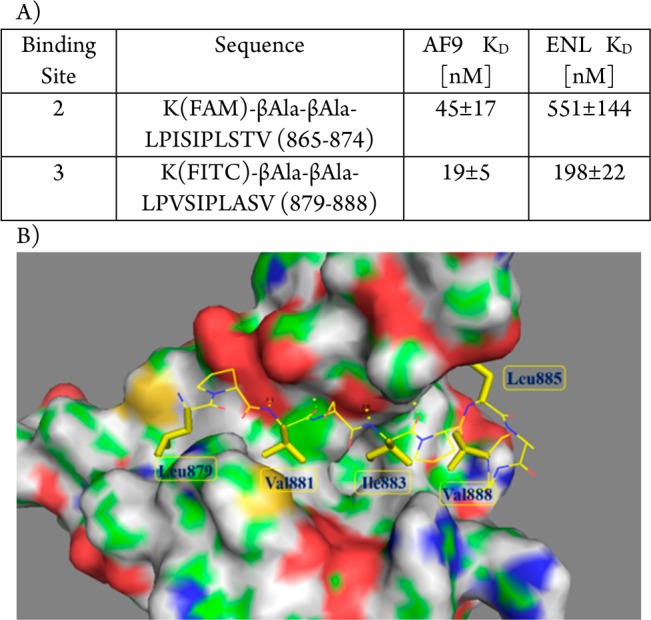

Our group characterized for the first time the protein–protein interactions between DOT1L and MLL fusion oncogenic proteins, AF9 and ENL, on the biochemical, biophysical, and functional level.10 This study mapped a 10 amino-acid region in DOT1L (aa 865–874) as the AF9/ENL binding site (peptide 1, Table 1). Peptide 1 binds to AF9/ENL and blocks the interaction between DOT1L and AF9/ENL in cell lysate.10 Importantly, functional studies show that the mapped 10-amino acid interacting site is essential for immortalization by MLL-AF9, indicating that DOT1L interaction and recruitment with MLL-AF9 are required for hematopoietic transformation.10 In an independent study using NMR spectroscopy, Kuntimaddi et al. confirmed the interaction site through the 10 mer peptide 1, labeled as site 2, and identified two additional DOT1L motifs: site 1 (aa 628–653) and site 3 (aa 878–900), which can bind to the same region in AF9 (aa 499–568) as site 2.18 The sequence between site 2 and site 3 is highly conserved, and they represent high-affinity binding motifs (Figure 1A). We synthesized two corresponding fluorescent labeled 10 mer peptides based on the sequence extracted from site 2 and site 3, respectively. Using a fluorescent polarization (FP) based assay, their binding affinities to AF9 and ENL were determined. Both peptides potently bound to AF9 and ENL, with the peptide derived from site 3 showing about 2 times more potent binding in comparison with the peptide derived from site 2 (Figure 1A). We and others have shown that DOT1L and AF4 bind with similar binding affinity and compete for the same AHD domain in AF9 and ENL protein.10,11,19 Consistently, NMR studies indicate that the AF4 protein11 as well as DOT1L binding motifs at sites 2 and 318 have similar binding modes to AF9. The NMR solution structure of the DOT1L–AF9 complex showed that DOT1L residues 879 to 884 from site 3 form a β strand (Figure 1B). The protein–protein interface is mainly hydrophobic and the side chains of L879, V881, I883, L885, and V888 have critical hydrophobic interactions with AF9 (Figure 1B). Furthermore, the amino and carbonyl groups of Val881 and Ile883 form two pairs of hydrogen bonds with Phe545 and Phe543 in AF9, respectively. These studies provide a concrete basis for using the DOT1L conserved binding motif (site 2 and site 3) as a promising lead structure toward the design of potent peptidomimetics and nonpeptidic compounds that target the interactions between MLL-AF9/ENL and DOT1L. In this Letter for the first time, we report the design and synthesis of DOT1L peptidomimetics that bind to the AF9 and ENL oncogenic fusion proteins and block their interactions with DOT1L.

Table 1. Optimization of the Middle Three Residues.

Figure 1.

(A) Binding affinity of 10 mer peptides derived from binding sites 2 and 3, respectively, against AF9 and ENL proteins; (B) NMR solution structure of the DOT1L–AF9 complex (PDB ID: 2MV7).

Results

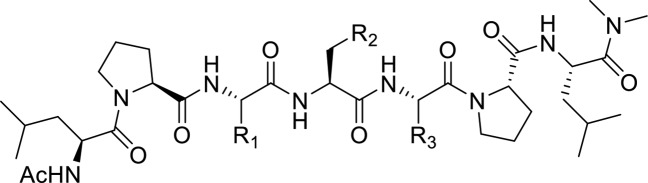

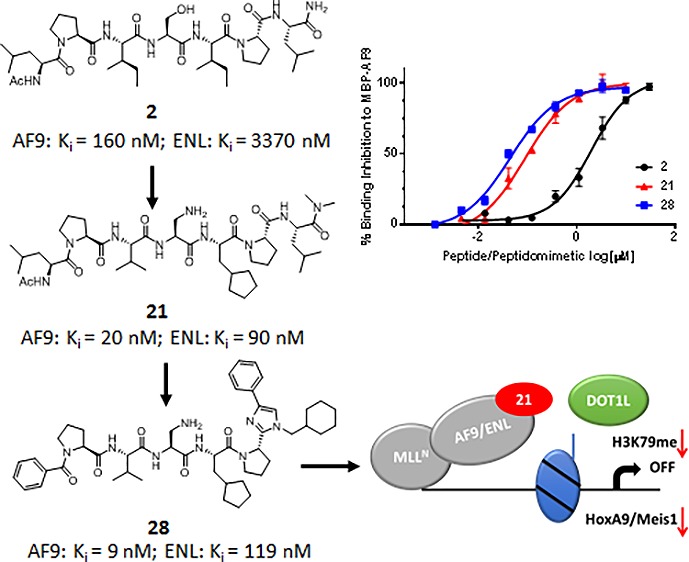

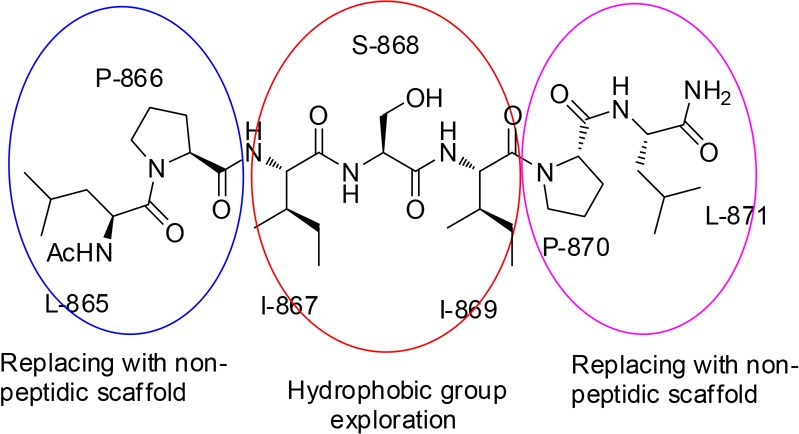

In our previous study,10 we performed alanine-scanning mutagenesis of DOT1L peptide 1 (Table 1), and mutating four critical hydrophobic residues, L865, I867, I869, and L871, led to significant decrease of their binding affinity to both AF9 and ENL proteins. Interestingly, mutation of the last three residues in the DOT1L 10 mer peptide was well tolerated and showed only a 2–6-fold decrease in the binding affinity in comparison with the wild type peptide.10 As expected, 7 mer peptide 2 showed reasonable binding affinity to AF9 with a Ki value of 0.16 μM, 8-fold less than 10 mer peptide 1 (Table 1). Importantly, the 7 mer peptide derived from site 3, peptide 3, showed identical binding affinity as 2 (Table 1), consistent with the binding affinities of the 10 mer peptides obtained from these two binding sites (Figure 1A). Therefore, in our follow up chemical modifications, 7 mer peptide 2 was selected as a promising lead structure for further optimization. Based on the structural information and essential key binding elements in DOT1L, we separated peptide 2 into three parts: the N-terminal two residues, the middle three residues, and the C-terminal two residues (Figure 2). We demonstrated that the I867 and I869 are critical hydrophobic residues that are buried within the DOT1L–AF9 interface.10 Therefore, the peptide scaffold of the middle three residues was preserved to maintain the hydrogen bonds with the protein, and the modifications were focused on the side chains of I867 and I869. In the N-terminal and C-terminal dipeptide moieties, the side chains of L865 and L871, respectively, have hydrophobic interactions with AF9. Thus, these two parts were replaced with nonpeptidic scaffolds and hydrophobic groups to mimic the side chains of these leucine residues.

Figure 2.

Modification strategy for 7 mer DOT1L peptide 2.

To improve the synthetic efficiency, we used a convergent method for the synthesis of the designed compounds by linking different fragments. Therefore, homogeneous reactions instead of solid phase synthesis were used. For the convenience of synthesis, we designed compound 4 by replacing the primary amide in 2 with a dimethylated tertiary amide. In our FP competitive binding assay, 4 binds to AF9 with a Ki value of 0.30 μM and is only slightly less potent than 2 and 3, indicating that this modification is not detrimental to the binding. To probe the hydrophobic interactions of I867, we designed compounds 5–9 where the isoleucine was replaced with a series of natural or unnatural amino acids. The binding results showed that this pocket is very sensitive to the modifications, and only when the isoleucine residue is replaced with valine can the binding affinity be slightly improved (5, Ki 0.17 μM). Introducing other amino acids at this position, such as leucine, cyclopropyl alanine, and cyclobutyl alanine, resulted in reduced binding affinity by 3–5-fold (compounds 6–8). Replacing isoleucine with a larger phenylalanine in 9 significantly decreased the binding by about 20-fold (Ki 5.62 μM), indicating that this pocket can accommodate a small hydrophobic group.

We then explored the hydrophobic interactions of I869. The NMR structure indicated that this pocket could accommodate a larger hydrophobic group, and therefore, we tried a series of amino acids with a larger hydrophobic side chain. Replacement of the isoleucine residue with a cyclopentyl glycine does not influence the binding affinity (10, Ki 0.25 μM). However, enlarging the five-membered ring to a six-membered ring decreases the binding affinity by 2-fold (11 vs 10). This might suggest that the pocket is not deep enough to accommodate a larger cyclohexyl group. Replacement of the isoleucine with leucine (12, Ki 0.83 μM) decreases the binding by 3-fold, but using an unnatural cyclopentyl methyl group at this position can slightly improve the binding affinity. The resulting compound 13 shows a Ki of 0.13 μM in our FP binding assay and is 2 times more potent than 4. Replacing the cyclopentyl ring in 13 with a cyclohexyl in 14 (Ki 0.18 μM) or a phenyl ring in 15 (Ki 0.28 μM) only slightly decreases the binding affinity. Replacing the cyclopentyl ring in 13 with a larger hydrophobic group, such as an indole (16) or a naphthyl group (17, 18), led to decreased binding in comparison with 13. 16 with a Ki 0.41 μM is about 3-fold less potent than 13, while the β-naphthyl group containing compound 17 is 5-fold less potent (Ki 0.73 μM). The α-naphthyl ring containing compound 18 shows a Ki value of 2.6 μM, being 15 times less potent than 13 and the least potent peptide in this series. Overall, among all the amino acids we have tried at this position, cyclopentyl alanine is the most optimal substitution for R3 (compound 13).

The AF9–DOT1L NMR complex structure showed that the side chain of serine residue, S882, is exposed to the solvent and has no interaction with the protein.18 Therefore, this residue was used to modify the physicochemical properties and solubility of the peptides, since the other residues are largely hydrophobic. Replacing serine with lysine dramatically decreases the binding affinity by 15-fold (19 vs 4), indicating that a larger group at this site is detrimental to the binding. Replacement of the hydroxyl group in the serine residue of 4 with an amino group led to compound 20, with a slightly improved Ki value of 0.19 μM. Combining the SAR information obtained from studying the middle three residues, we designed compound 21. Interestingly, this compound binds to AF9 with a Ki of 0.02 μM, being 10 times more potent than 4 and as potent as the 10 mer peptide 1. All of these compounds have been tested for their binding to the highly homologous ENL protein (Table 1). The results indicated that these compounds bind to ENL with 5–10 times less potent binding affinities in comparison to AF9, consistent with the binding profile of 10 mer DOT1L peptide 1.

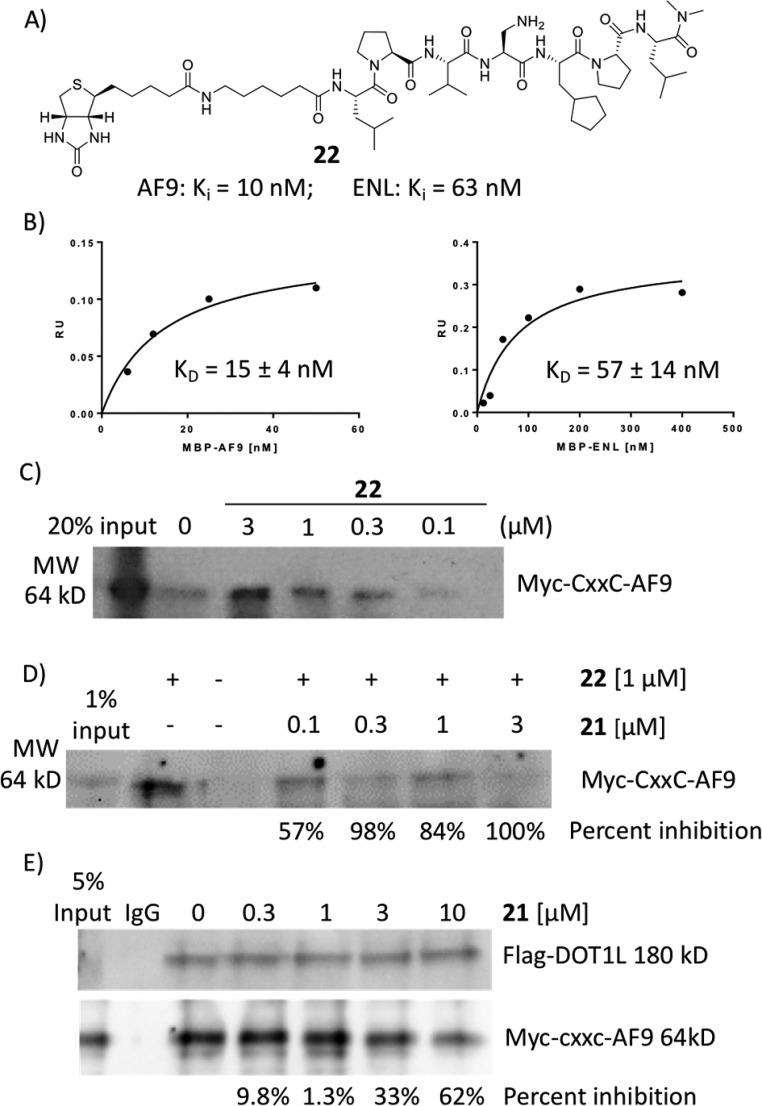

To further confirm the binding affinity of the most potent compound 21 and to determine whether 21 recognizes and binds cellular oncofusion proteins, a biotin-labeled analog 22 was synthesized (Figure 3A). As was expected, biochemical assays show that 22 has similar low nanomolar binding affinities as 21 to AF9 and ENL recombinant proteins. In FP binding assay, 22 shows Ki values of 10 nM and 63 nM to AF9 and ENL, respectively. Using biolayer interferometry assay (BLI), it was determined that this compound binds to AF9 and ENL with KD values of 15 nM and 57 nM, respectively (Figure 3B), consistent with the Ki values obtained by the competitive FP assay. The recombinant proteins used for the binding studies are tagged with maltose binding protein (MBP) to preserve the stability and solubility of the intrinsically disordered AHD domain of AF9 and ENL proteins. The specific interactions of compound 22 with fusion proteins were confirmed by testing it for its binding to the MBP tag protein only and did not show any binding (Supporting Information Figure S1). To assess whether peptide 22 can bind to the cellular AF9 oncofusion protein, we have transfected HEK 293t cells with Myc-tagged CxxC-AF9 protein. In streptavidin–biotin pull-down experiments, compound 22 efficiently pulls down cellular Myc-CxxC-AF9 protein in a dose dependent manner using HEK 293t cell lysates (Figure 3C). Moreover, in a competitive pull-down assay, compound 21 dose dependently inhibits the binding of biotinylated compound 22 to the cellular Myc-CxxC-AF9 protein, with approximately 60% inhibition at 100 nM (Figure 3D). To test if the most potent compound 21 can disrupt the MLL–AF9–DOT1L interaction in cells, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiment in HEK 293t cells cotransfected with Flag-DOT1L and Myc-CxxC-AF9 (Figure 3E). DOT1L was equally pulled down and in the absence of 21, the AF9 was efficiently co-IPed showing intact DOT1L–AF9 complex. Incubation of the cell lysates with 21 disrupted the DOT1L-AF9 complex in a dose-dependent manner. Together these experiments demonstrate that both compounds 21 and biotinylated 22 recognize and bind to the cellular AF9 protein, and 21 effectively inhibits the DOT1L–AF9 interaction in cells.

Figure 3.

Biotinylated compound 22. (A) Chemical structure and Ki values obtained by FP based binding assay; (B) Binding affinity determined by BLI against two oncofusion proteins, AF9 and ENL; (C) Pull down assay using HEK 293t cells transiently transfected with Myc-CxxC-AF9. (D) Compound 21 in a competitive manner inhibits binding of biotinylated 22 to cellular Myc-CxxC-AF9. (E) Co-IP experiment in HEK 293t cells cotransfected with Flag-DOT1L and Myc-CxxC-AF9.

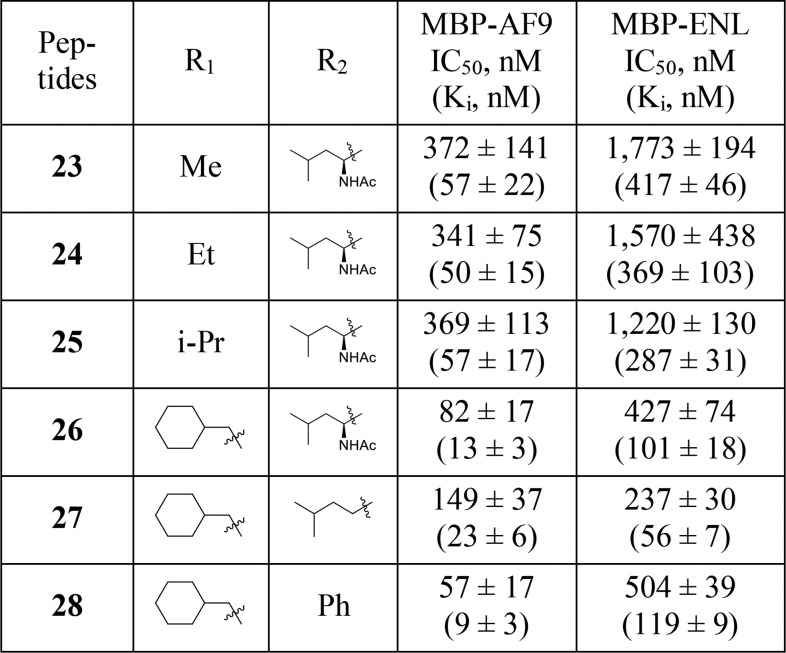

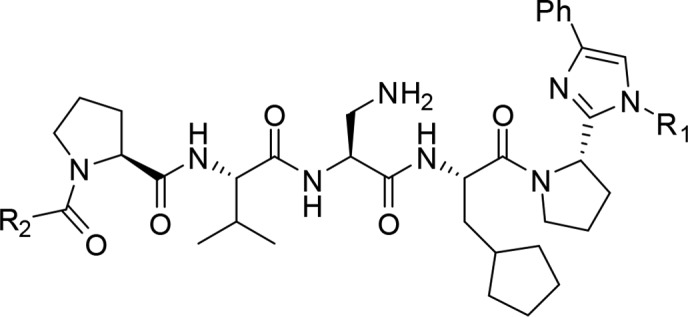

Toward the development of DOT1L peptidomimetics, preliminary studies were performed for the modifications of both the C- and N-termini. In the following design, the middle three residues were kept as in the most potent compound 21. Both the C- and N-terminal dipeptide motifs contain a proline residue and a leucine residue. Among all-natural amino acids, proline is unique in that it can strongly influence the conformation of the peptide; therefore, in our initial studies the pyrrolidine ring was kept on both termini. In peptide modifications, replacing the amide bond with a heteroaromatic ring is a frequently used method to mimic the planar structure of the amide and to improve the metabolic stability. Thus, for the C-terminal modifications we designed compounds 23–26 by replacing the amide bond between proline and leucine with an imidazole ring and by introducing substitute groups to mimic the side chain of leucine involved in interaction with AF9 (Table 2). In these compounds, a phenyl ring was introduced to the C4 position of the imidazole and various hydrophobic groups were introduced to the N1, respectively. These compounds have been tested in the FP competitive binding assay, and the results indicated that compounds with a small hydrophobic group on N1 (23–25) have decreased binding affinity comparing with 21. However, compound 26 which has a cyclohexyl group on N1 shows a Ki value of 13 nM to AF9 and is slightly more potent than 21. These results suggest that a larger hydrophobic group at N1 could bind to a bigger hydrophobic pocket and improve the binding affinity.

Table 2. Modification of the C-Terminal and N-Terminal Dipeptidic Motifs.

The acetylamido group at the N-terminus is exposed to the solvent and does not interact with the protein. Therefore, we designed compound 27 by removing this group. Compound 27 has a Ki value of 23 nM for AF9 protein and is about two times weaker than 26, indicating that the acetylamido group could play a role in controlling the orientation of the hydrophobic side chain of the leucine residue. We then designed compound 28 by replacing the 2-methyl-butyl group in 27 with a phenyl ring. This compound binds to AF9 with a Ki value of 9 nM, about 3 times more potent than 27 and 2 times more potent than 21, indicating that nonpeptidic modifications of the two terminal residues not only can reduce the peptidic characteristic of the compounds but can also improve the binding affinity.

These compounds have also been evaluated for their binding affinities to ENL. Similar to the 7 mer analogs, the C-terminal modified compounds 23–26 bind to ENL 5–10-fold less potently than to AF9. However, the N-terminal modified compounds 27 and 28 show a different trend. 27 binds to ENL with a Ki value of 56 nM and is only 2–3 times less potent to AF9, but 28 binds to AF-9 13-fold more potently than to ENL, suggesting that N-terminal modifications could alter the selectivity in binding to the two fusion proteins.

In summary, based on the 7 mer DOT1L peptide, a series of peptidomimetics was designed and synthesized to improve the binding affinity to AF9 and decrease the peptidic characteristics. By optimizing the middle three residues we identified peptide 21, which has a significantly improved binding affinity compared to the original peptide 2. Based on 21, we have performed preliminary modifications to both the C- and N-termini of 21. For the C-terminal dipeptide motif we found that the amide bond in the dipeptide can be replaced with an imidazole ring and hydrophobic groups can be introduced to the imidazole ring to mimic the hydrophobic interaction of the DOT1L leucine residue L871. For the N-terminal dipeptide motif, replacement of the leucine residue L865 with a suitable hydrophobic group can improve the binding affinity. Detailed modifications to the C- and N-terminal residues and the mechanistic studies for the designed compounds are proceeding, and the results will be reported subsequently.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00175.

Experimental details for the synthesis of the designed compounds, characterization data, fluorescence polarization (FP) binding assay, biolayer interferometry (BLI) binding studies, pull-down and co-IP experiments (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ L.D. and S.M.G. contributed equally.

This work was supported by the UM Center for Discovery of New Medicine (CDNM) to Z.N–C. The National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program and Rackham Merit Fellowship to S.M.G. The Program for Jiangsu Province Innovative Research Team, the Program for Jiangsu Province Innovative personnel and the Program for Specially Appointed Professor of Jiangsu Province to H.S.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Muntean A. G.; Hess J. L. The pathogenesis of mixed-lineage leukemia. Annu. Rev. Pathol.: Mech. Dis. 2012, 7, 283–301. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A. Transcriptional activation by MLL fusion proteins in leukemogenesis. Exp. Hematol. 2017, 46, 21–30. 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivtsov A. V.; Armstrong S. A. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 823–833. 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.; Smith E. R.; Takahashi H.; Lai K. C.; Martin-Brown S.; Florens L.; Washburn M. P.; Conaway J. W.; Conaway R. C.; Shilatifard A. AFF4, a component of the ELL/P-TEFb elongation complex and a shared subunit of MLL chimeras, can link transcription elongation to leukemia. Mol. Cell 2010, 37, 429–437. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A.; Lin M.; Naresh A.; Kitabayashi I.; Cleary M. L. A higher-order complex containing AF4 and ENL family proteins with P-TEFb facilitates oncogenic and physiologic MLL-dependent transcription. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 198–212. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan M.; Herz H. M.; Takahashi Y. H.; Lin C.; Lai K. C.; Zhang Y.; Washburn M. P.; Florens L.; Shilatifard A. Linking H3K79 trimethylation to Wnt signaling through a novel Dot1-containing complex (DotCom). Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 574–589. 10.1101/gad.1898410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J.; Jones M.; Koseki H.; Nakayama M.; Muntean A. G.; Maillard I.; Hess J. L. CBX8, a polycomb group protein, is essential for MLL-AF9-induced leukemogenesis. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 563–575. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger D. J.; Lefterova M. I.; Ying L.; Stonestrom A. J.; Schupp M.; Zhuo D.; Vakoc A. L.; Kim J. E.; Chen J.; Lazar M. A.; Blobel G. A.; Vakoc C. R. DOT1L/KMT4 recruitment and H3K79 methylation are ubiquitously coupled with gene transcription in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 2825–2839. 10.1128/MCB.02076-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.; Lin C.; Guest E.; Garrett A. S.; Mohaghegh N.; Swanson S.; Marshall S.; Florens L.; Washburn M. P.; Shilatifard A. The super elongation complex family of RNA polymerase II elongation factors: gene target specificity and transcriptional output. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 2608–2617. 10.1128/MCB.00182-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C.; Jo S. Y.; Liao C.; Hess J. L.; Nikolovska-Coleska Z. Targeting recruitment of disruptor of telomeric silencing 1-like (DOT1L): characterizing the interactions between DOT1L and mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) fusion proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 30585–30596. 10.1074/jbc.M113.457135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach B. I.; Kuntimaddi A.; Schmidt C. R.; Cierpicki T.; Johnson S. A.; Bushweller J. H. Leukemia fusion target AF9 is an intrinsically disordered transcriptional regulator that recruits multiple partners via coupled folding and binding. Structure 2013, 21, 176–183. 10.1016/j.str.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivtsov A. V.; Feng Z.; Lemieux M. E.; Faber J.; Vempati S.; Sinha A. U.; Xia X.; Jesneck J.; Bracken A. P.; Silverman L. B.; Kutok J. L.; Kung A. L.; Armstrong S. A. H3K79 methylation profiles define murine and human MLL-AF4 leukemias. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 355–368. 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernt K. M.; Zhu N.; Sinha A. U.; Vempati S.; Faber J.; Krivtsov A. V.; Feng Z.; Punt N.; Daigle A.; Bullinger L.; Pollock R. M.; Richon V. M.; Kung A. L.; Armstrong S. A. MLL-rearranged Leukemia is Dependent on Aberrant H3K79 Methylation by DOT1L. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 66–78. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A. T.; Taranova O.; He J.; Zhang Y. DOT1L, the H3K79 methyltransferase, is required for MLL-AF9–mediated leukemogenesis. Blood 2011, 117, 6912–6922. 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle S. R.; Olhava E. J.; Therkelsen C. A.; Majer C. R.; Sneeringer C. J.; Song J.; Johnston L. D.; Scott M. P.; Smith J. J.; Xiao Y.; Jin L.; Kuntz K. W.; Chesworth R.; Moyer M. P.; Bernt K. M.; Tseng J.-C.; Kung A. L.; Armstrong S. A.; Copeland R. A.; Richon V. M.; Pollock R. M. Selective Killing of Mixed Lineage Leukemia Cells by a Potent Small-Molecule DOT1L Inhibitor. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 53–65. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A. T.; Zhang Y. The diverse functions of Dot1 and H3K79 methylation. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1345–1358. 10.1101/gad.2057811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S. Y.; Granowicz E. M.; Maillard I.; Thomas D.; Hess J. L. Requirement for Dot1l in murine postnatal hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis by MLL translocation. Blood 2011, 117, 4759–4768. 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntimaddi A.; Achille N. J.; Thorpe J.; Lokken A. A.; Singh R.; Hemenway C. S.; Adli M.; Zeleznik-Le N. J.; Bushweller J. H. Degree of recruitment of DOT1L to MLL-AF9 defines level of H3K79 Di- and tri-methylation on target genes and transformation potential. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 808–820. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson V. G.; Drake K. M.; Peng Y.; Napper A. D. Development of a high-throughput screening-compatible assay for the discovery of inhibitors of the AF4-AF9 interaction using AlphaScreen technology. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2013, 11, 253–268. 10.1089/adt.2012.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.