Abstract

Importance. Acupuncture can help reduce unpleasant side effects associated with endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Nevertheless, comprehensive evaluation of current evidence from randomized controlled trials(RCTs) is lacking. Objective. To estimate the efficacy of acupuncture for the reduction of hormone therapy-related side effects in breast cancer patients. Evidence review. RCTs of acupuncture in breast cancer patients that examined reductions in hormone therapy–related side effects were retrieved from PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Ovid MEDLINE, and Cochrane Library databases through April 2016. The quality of the included studies was evaluated according to the 5.2 Cochrane Handbook standards, and CONSORT and STRICTA (Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture) statements. Intervention. Interventions included conventional acupuncture treatment compared with no treatment, placebo, or conventional pharmaceutical medication. Major outcome measures were the alleviation of frequency and symptoms and the presence of hormone therapy–related side effects. Findings/Results. A total of 17 RCTs, including a total of 810 breast cancer patients were examined. The methodological quality of the trials was relatively rigorous in terms of randomization, blinding, and sources of bias. Compared with control therapies, the pooled results suggested that acupuncture had moderate effects in improving stiffness. No significant differences were observed in hot flashes, fatigue, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, Kupperman index, general well-being, physical well-being, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin (IL). Conclusions. Acupuncture therapy appears to be potentially useful in relieving functional stiffness. However, further large-sample trials with evidence-based design are still needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: acupuncture, hormone therapy–related side effects, breast cancer, systematic review, quality of life

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer-related death among women. Hormonal therapy, a standard breast cancer adjuvant therapy, is one of the most widely used treatments for breast cancer patients and effectively reduces death and recurrence from breast cancer. Hormone treatments are effective against many types of breast cancer, but are, nevertheless, accompanied by side effects, including vasomotor syndrome, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, pain, hot flashes, and psychological stress.1 These side effects present major hurdles to increasing the effectiveness of cancer treatment and can adversely affect quality of life, compliance with treatment, and overall survival. Important aspects of breast cancer therapy include relieving cancer-related pain,2,3 fatigue,4 and hot flashes5 and improving the quality of life.6,7

More than 11.2% of patients have used acupuncture as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in breast cancer treatment.8 Acupuncture use among breast cancer patients in the United States is currently as high as 16% to 63%.9,10 An increasing number of studies indicate that acupuncture can be used in treatment-related symptom control11 and the alleviation of side effects caused by hormone treatment.7,12 Acupuncture plays an important role in improving the overall quality of life of breast cancer patients.13

The clinical application of needle therapy in ancient China is one of the oldest of the healing arts; this ancient form of treatment is gaining popularity as part of the contemporary CAM therapy movement today. Most literature has reported that acupuncture is a potentially beneficial, gentle treatment for cancer survivors, and research on acupuncture in breast cancer populations continues to attract growing attention, supplemented and supported by conservative optimism.14 However, other studies reported no beneficial effect.15-18 The aim of this meta-analysis, therefore, was to assess the efficacy of acupuncture for treatment-related side effects of hormone therapy and the quality of life of patients with breast cancer.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

A search was performed for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) studying the clinical benefits of acupuncture for the reduction of hormone therapy–related side effects in breast cancer patients. Only English-language published literature was searched; no publication date or status restrictions were imposed. We included women participants if they were (1) aged 18 years or older, (2) had a history of breast cancer, and (3) received active breast cancer treatments and/or were administered hormone therapy. Patients with prior acupuncture use for aromatase inhibitor (AI)-induced joint symptoms or acupuncture within 6 months before enrollment were excluded. All types, doses, and regimens of acupuncture and electroacupuncture versus a placebo or control group were included. Primary outcome measures were hormone therapy–related side effects; a secondary outcome measure was physical well-being.

Data Sources and Searches

Studies were identified by searching databases, scanning reference lists, and consultation with breast cancer and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) experts. The databases included PubMed (1966 to November 2017), EMBASE (1974 to November 2017), the Cochrane Library (issue 4 through 2017), and the Web of Science (1974 to November 2017) using the following terms: (“breast neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR “breast neoplasm”[Title/Abstract] OR “breast cancer”[Title/Abstract] OR “breast tumor”[Title/Abstract] OR “breast neoplasms”[Title/Abstract] OR “breast cancers”[Title/Abstract] OR “breast tumors”[Title/Abstract]) AND “electro-acupuncture” [MeSH Terms] OR “electro-acupuncture”[Title/Abstract] OR “Electroacupuncture” [MeSH Terms] OR “Electroacupuncture”[Title/Abstract] OR (“Acupuncture”[MeSH Terms] OR “Acupuncture”[Title/Abstract]) AND (random* OR “Clinical Trials as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Clinical Trial” [Publication Type]). Reference lists were reviewed to identify additional studies, and the final bibliography was distributed to experts to identify missing studies.

Data Abstraction and Assessment of Bias Risk

This systematic review was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook version 5.2. Three reviewers (Yuanqing Pan, Xiue Shi, and Haiqian Liang) independently selected studies by screening titles, abstracts, and the included studies after scanning the full texts. The following information was extracted: (1) trial participant characteristics (including age, stage, current treatment, duration, and outcome measures) and (2) type of intervention (including type, dose, duration, and frequency of acupuncture) versus the placebo/control group. Further information was obtained from study authors when needed. Risk of bias was assessed according to the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook19 and evaluated sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of the study participants and investigators, whether incomplete outcome data were addressed, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. Three authors independently performed data extraction and quality assessment. All disagreements during study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment were resolved by consensus or discussions with a third author.

Data Analysis

For continuous outcomes, the standardized mean difference or mean difference and 95% CI were calculated. Binary outcomes were pooled by using an odds ratio and 95% CI. A subgroup analysis was conducted according to the end point measurement methods and evaluated subjects. The meta-analysis was performed with Stata software (version 10.0, Stata Corp, College Station, TX).20

Results

Description of Studies

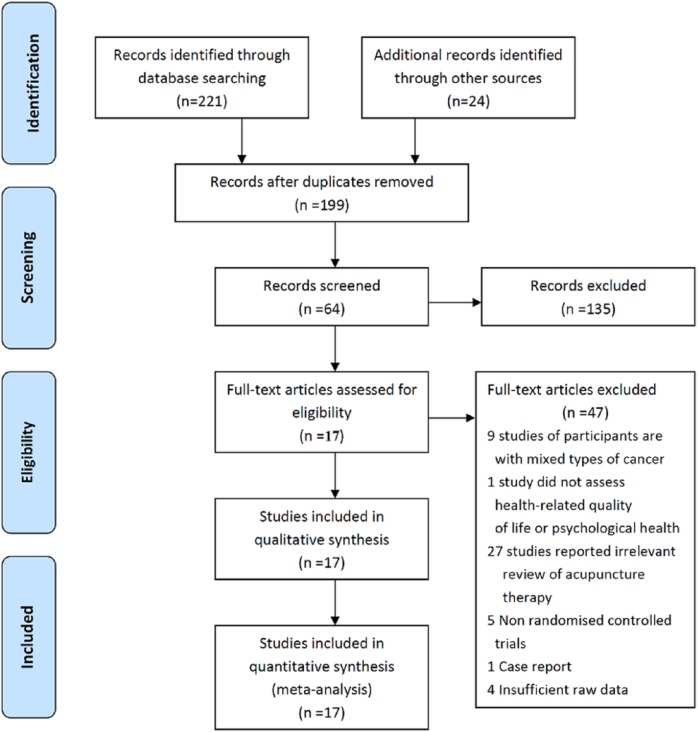

A total of 245 studies were identified by searching the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Ovid MEDLINE, and Cochrane Library databases; 46 duplicates and 182 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria and were subsequently excluded. The baselines of the trials were comparable. The selection process is shown in Figure 1. A total of 17 studies were included.2-7,15-18,21-27 Tables 1 and 2 summarize the characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the results of the literature search.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies.

| Authors/Year/Country | No. of Patients (Acupuncture Group/Control Group) | Mean Age of Acupuncture Group (years) | Mean Age of Control Group (years) | Status of Cancer | Current Treatment | Hormone Therapy | Duration | Outcome Measures/Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bao et al, 2013,2 United States | 23/24 | 61 (44-82) | 61 (45-85) | 0-III | Hormone replacement therapy, letrozole, anastrozole, exemestane | Letrozole and/or anastrozole, and/or exemestane, ≥1 month | 8 Weeks | Significant improvements in HAQ-DI (P < .03), pain (VAS), significant reduction of IL-17 (P < .009), no significant modulation was seen in estradiol, β-endorphin, or other proinflammatory cytokine (P > .05) |

| Crew et al, 2007,3 United States | 9/9 | 47 ± 1.1 Of 11 patients (52%) who reported taking analgesics (acetaminophen, NSAIDs, or COX-2 inhibitors) at baseline | 43 ± 1.5 | II-III | Medicated with tamoxifen, postoperative radiation and chemotherapy | Letrozole and/or anastrozole, and/or exemestane, 6 months | 6 Weeks | Significant improvements in anxiety (HADS-A; P < .001), depression (HADS-D; P < .001), and PSS in true acupuncture group (P < .001) |

| Crew et al, 2010,4 United States | 20/18 | 58 (44-77) | 57 (37-77) | I-III | Medicated with tamoxifen, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy | Letrozole and/or anastrozole, and/or exemestane, 6 months | 6 Weeks | Significant improvement in pain and physical well-being (BPI, P < .01; WOMAC, P < .01), significant improvement in quality of life (FACT-B and BPI-SF; P < .01) in true acupuncture group |

| Deng et al, 2007,15 United States | 42/30 | 53.5 | 54 | Unclear | Medicated with tamoxifen, postoperative radiation and chemotherapy, SSRIs | Tamoxifen and/or aromatase inhibitors, within 3 weeks | 4 Weeks | No significant improvement in hot flashes/24 in true acupuncture group (P > .05) |

| Nedstrand et al, 2005,27 Sweden | 19/19 | 53 | Unclear | Unclear | Medicated with tamoxifen, postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy | Tamoxifen treatments mentioned, no details | 6 Months | Significant reduction in hot flushes (P < .0001) in both groups, significant reduction in KI (P < .0001) in both groups |

| Frisk et al, 2008,23 Sweden | 36 | 56.5 | 53.4 | I - III | Medicated with Tamoxifen, postoperative radiation and chemotherapy | >2 Years sequential estrogen/progestagen combination, >2 years after menopause, given combined estrogen/progestagen | 6 months | Significant reduction in hot flushes (P < .001) in the electroacupuncture group, significant reduction in KI in both groups (P < .05) |

| Hervik and Mjåland, 2009,21 Norway | 30/29 | 53.6 ± 6.4 | 52.3 ± 6.9 | Unclear | Postoperative radiation and chemotherapy | Tamoxifen for at least 3 months, mentioned, no details | 6 Weeks | Significant reduction in hot flashes (P < .001) in both groups; significant reduction in KI in true acupuncture group (P < .0001) and small reduction (P = .06) in the sham acupuncture group |

| Hervik and Mjåland, 2014,22 Norway | 43/45 | 52.5 | 50.2 | Unclear | Postoperative, medicated with tamoxifen | Tamoxifen for 3 months | 10 Weeks | Significant reduction in KI |

| Johnston et al, 2011,5 United States | 5/7 | 55 ± 6.40 | 53 ± 7.2 | Unclear | Medicated with hormone replacement therapy, postoperative radiation, and chemotherapy | Hormone replacement therapy mentioned, no details | 8 Weeks | Significant decline in fatigue (BFI; P < .10) in true acupuncture group, no significant improvement in cognitive dysfunction (FACT-B; P > .05) in true acupuncture group |

| Liljegren et al, 2012,6 Sweden | 38/36 | 58 ± 6.8 | 58 ± 9.3 | I | Medicated with tamoxifen, and chemotherapy | Tamoxifen treatments mentioned, at least 2 months | 6 Weeks | Significant reduction in hot flushes (P < .001), significant improvement in physical well-being (WOMAC; P < .01) |

| Mao et al, 2014,18 United States (I) | 19/21 | 57.5 ± 10.1 | 60.9 ± 6.5 | I-III | Postoperative, medicated with tamoxifen, and chemotherapy | Anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane | 12 Weeks | Significant improvements in pain (BPI; P < .00), stiffness (WOMAC; P < .0.00); no significant improvement on upper PPT (P > .05) |

| Mao et al, 2014,24 United States (II) | 19/21 | 57.5 ± 10.1 | 60.9 ± 6.5 | I-III | Hormone therapy | Anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane | 12 Weeks | Significant improvements in fatigue (BFI; P < .0095), anxiety (HADS; P < .044), depression (HADS; P < .015), and sleep disturbance (PSQI; P < .058) |

| Mao et al, 2015,25 United States | 30/32 | 52.9 ± (8.6) | 52 ± (8.9) | I-III | Hormone replacement therapy | Tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitor mentioned, no details | 8 Weeks | Significant reduction in hot flash composite score (HFCS; P < .001) |

| Molassiotis et al, 2013,16 United Kingdom | 56/49 | 46 | 53 | I-IIIa | Medicated with tamoxifen, postoperative radiation and chemotherapy | Hormone treatments mentioned, no details | 10 Weeks | No significant improvement in fatigue (MFI; P > .05), emotional well-being (HADS; P > .05), and quality of life (FACT-B; P > .05) |

| Nedstrand et al, 2006,7 Sweden | 17/14 | 30-64(53) | Unclear | Unclear | Postoperative radiation and chemotherapy | Tamoxifen treatments mentioned, at least 12 weeks | 6 months | Significant reduction in hot flashes (P < .001), significant reduction in KI (P < .0001), significant reduction in pain (VAS; P < .0001) in both groups, significant improvement in psychological well-being (SCL; P < .0001) in both groups, mood improved significantly (MS; P < .0001) in the electroacupuncture group |

| Smith et al, 2013,17 Australia | 10/10 | 55 ± 8.8 | 53 ± 12.5 | Unclear | Surgical treatment | Hormone treatments mentioned, no details | 6 Weeks | No significant reduction in fatigue (BPI-SF; P > .05), significant improvement in quality of life (MYCaW; P = .006) |

| Yao et al, 2016,26 Korea | 15/15 | 56.2 ± 5.82 | 55.8 ± 5.02 | Chemotherapy, radiation therapy | Not mentioned | 6 Weeks | Lymphedema, significant improvement (P < .0000); shoulder range of motion, significant improvement (P < .0000); quality of life (QLQ-30), significant improvement (P < .05) |

Abbreviations: BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory–Short Form; COX, cyclo-oxygenase; FACT-B, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IL, interleukin; KI, Kupperman Index; MFI, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; MS, Mood Scale; MYCaW, Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing questionnaire; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PPT, Physical Performance Test; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SCL, Symptom Checklist; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Subscales of Depression; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Subscales of Anxiety; HFCS, Hot Flash Composite Score; QLQ, Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Acupuncture Prescription.

| Author/Year | Inclusion Criteria | Instructor | Needles | Points | Treatment Group | Control Group | Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bao et al, 2013,2 United States | Clinical experience of acupuncturists | No mention | 0.25 mm × 40 mm Sterilized and disposable acupuncture needles (DongBang AcuPrime, United Kingdom) | CV 4, CV6, CV12, bilateral LI 4, MH 6, GB 34, ST 36, KI 3, BL 65 | 8 Weeks | Sham needles | Qi (vital energy) deficiency |

| Crew et al, 2007,3 United States | STRICTA | Acupuncturists | Single-use, sterile, and disposable; full-body acupuncture needles were 25 mm or 40 mm and 34 gauge (G; Cloud & Dragon, Wujiang City Cloud & Dragon Medical Device Co, Ltd, China), and auricular needles were 15 mm and 38 G (Seirin, Seirin-America Inc, Weymouth, MA) | SJ5, GB41, GB34, LI 4, ST41, KD 3, LI15, SJ14, SI10, SJ4, LI5, SI5, SI3, LI3, DU-3, DU8, UB23, GB39 GB30, SP9, SP10, ST34 | 20-25 Minutes, twice weekly for 6 weeks | No treatment, observation at baseline | Pain and pain-related functional interference, gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Crew et al, 2010,4 United States | National Acupuncture Detoxification Association protocol | Acupuncturists | 25 mm or 40 mm and 34 G (Cloud & Dragon Medical Device, Wujiang City, China), and auricular needles were 15 mm and 38 G (Seirin-America, Weymouth, MA) | Standardized set of acupuncture points, no details | 20-25 Minutes, twice weekly over 6 weeks | No treatment, observation at baseline | Pain, physical function, gastrointestinal symptoms, quality of life |

| Deng et al, 2007,15 United States | Referring to the published literature | Experienced physiotherapist | Stainless steel filiform, needles sized 0.20 mm × 30 mm, manufactured by Seirin Corp (Shizuoka, Japan) | DU14, GB 20, BL 13, PC7, H6, K7, ST36 | 20 Minutes, twice-weekly treatments for 4 weeks | Sham needles | Hot flushes |

| Nedstrand et al, 2005,27 Sweden | Referring to the published literature | Experienced physiotherapist | 12 Sterile, stainless steel acupuncture needles were inserted to a depth of 5-20 mm in defined points | BL15, BL23, BL32 bilaterally, HT7, SP6, SP9, LR 3, PC6, GV20 | 30 Minutes twice a week for the first 2 weeks and once a week for 10 weeks | Progressive relaxation programs | Hot flashes |

| Frisk et al, 2008,23 Sweden | Referring to the published literature | Experienced physiotherapist | 2 Hz Electroacupuncture | Unclear | Electroacupuncture: 30 minutes twice a week for the first 2 weeks and once a week for another 8 weeks | No treatment, observation at baseline | Hot flashes |

| Hervik and Mjåland, 2009,21 Norway | Traditional Chinese medical textbooks | Physiotherapist with a 3-year certified training course from acupuncture school | Disposable 0.30-mm needles inserted between 0.5 and 3.0 cm | LIV3, GB20, LU7, KI3, SP6, REN4, P7, LIV8 | 30-Minute sessions twice weekly for the first 5 weeks | Sham needles | Hot flashes |

| Hervik and Mjåland, 2014,22 Norway | Mention | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 10 Weeks | Sham needles | Hot flashes |

| Johnston et al, 2011,5 United States | Referring to the published literature | Acupuncturists | LEKON sterile disposable acupuncture needles of the following sizes: 34 G × 1.5 (0.22 mm × 40 mm diameter); 34 G × 1.0 (0.22 mm × 25 mm); 32G × 1.5 (0.25 mm × 40 mm); and 38G × 0.5 (0.18 mm × 13 mm) | Li4, SP6, ST36, KI3, P6, SP4, LU7, KI4, LIV3, GV20, H7, UB62, GB20, TE5, GB43, SI3, UB62, GB29, GB30, GB40 | 50-Minute sessions for 8 weeks, frequency not mentioned | Normal practice included pharmacological and nonpharmacological options | Fatigue, cognitive dysfunction |

| Liljegren et al, 2012,6 Sweden | Referring to the published literature | Acupuncturists | 8 Sterilized disposable needles sized 0.25 mm × 40 mm manufactured by DongBang acupuncture Inc were inserted to a depth of 5-20 mm | LI4, HT6, LR3, ST36 unilaterally and SP6 and KI7 bilaterally | 20 Minutes twice a week for 5 weeks | Sham needles | Hot flushes, sweating, gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Mao et al, 2014,18 United States (I), Europe | Manualized protocol of traditional Chinese medicine theory | Nonphysician acupuncturists | 30 mm Or 40 mm and 0.25 G; Seirin-America Inc, Weymouth, MA | 4 Points around the joint with the most pain | 2-Hz electrostimulation of electroacupuncture: 30 minutes twice weekly for 8 weeks | Waitlist control | Pain, stiffness |

| Mao et al, 2014,24 United States (II) | Manualized protocol of traditional Chinese medicine theory | Nonphysician acupuncturists | 30 mm Or 40 mm and 0.25 G; Seirin-America Inc, Weymouth, MA | 4 Points around the joint with the most pain | 2-Hz electrostimulation of electroacupuncture: 30 minutes twice weekly for 8 weeks | Waitlist control | Depression, anxiety, fatigue |

| Mao et al, 2015,25 United States | Semistandardized treatment manual on the basis of existing literature | Nonphysician acupuncturists with 8 and 20 months experience | Bilateral 2-Hz electroneedles, 30 or 40 mm and 0.25 mm G; Seirin-America, Weymouth, MA, left in position for 30 minutes | Standard points depending on subjects’ preferred positions and presenting symptoms (eg, fatigue and insomnia) | Twice per week for 2 weeks, once per week for next 6 more weeks, 8 weeks total | Sham needles, selecting the same number of nonacupuncture trigger points | Hot flushes |

| Molassiotis et al, 2013,16 United Kingdom | Referring to the published literature; reporting in STRICTA | Experienced instructor | Seirin with guide tubes for single use and their size 36 G/point 16-30 mm | ST36, SP6, LI4 | 20 Minutes per week for 6 weeks | Health education for self-acupuncture | Fatigue, emotional well-being |

| Nedstrand et al, 2006,7 Sweden | Referring to the published literature | No mention | 12 Sterile stainless steel acupuncture needles were inserted to a depth of 5-20 mm at defined point | Four needles in the lower back, BL 23 and 32 bilaterally | Electroacupuncture: 30 minutes twice a week for the first 2 weeks and once a week for another 10 weeks | Progressive relaxation programs | Climacteric symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, emotional well-being |

| Smith et al, 2013,17 Australia | Referring to the published literature reporting in STRICTA | Acupuncturists | Single-use disposable stainless steel Vinco needles (0.25 mm × 40 mm and 0.22 mm × 25 mm) | KI3, KI27, ST36, SP6, CV4, CV6 | 20 Minutes for 6 weeks | Health education for self-acupuncture | Pain |

| Yao et al, 2016,26 Korea | Referring to the published literature | Professional medical practitioners | 0.45 mm × 25 mm needles: Suzhou Medical Instruments, Suzhou City, China) thermoacupuncture | Shousanli (LI.10), Quchi (LI.11), Binao (LI.14), Jianyu (LI.15), Waiguan (SJ.5), and Jianliao (SJ.14) | 30 Minutes on alternate days for 30 days | 900 mg Diosmin tablets, orally 3 times daily for 30 days | Lymphedema |

Abbreviation: STRICTA, Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture.

Study Characteristics

A total of 13 RCTs were from Northern Europe6,7,9,16,22,23,27 and North America,2-5,16,18,24,25 1 was from Australia,17 and 1 was from Korea.26 Participant age across all RCTs ranged from 30 to 61 years; 1 RCT included patients with stage 0-III breast cancer, 1 included patients with stage II-III tumors,3 and 7 RCTs included patients with stage I-III breast cancer,4,6,16,18,24,25 whereas the others did not provide complete details. Participants in 9 RCTs were administered tamoxifen, postoperative radiation, and chemotherapy during the acupuncture intervention3-5,7,9,16,23,27; participants in 3 RCTs underwent no postoperative hormone therapy before study onset2,24,25; and those in 2 RCTs received postoperative hormone therapy.17,22 Participants in 2 RCTs6,18 underwent postoperative hormone therapy and chemotherapy during the acupuncture intervention. Program intensities varied, ranging from twice weekly from 20 to 30 minutes each, with treatment durations ranging from 4 to 10 weeks. Acupuncture prescriptions varied in needling protocol, points, and meridian systems; indications for acupuncture mainly focused on hot flashes, fatigue, pain, joint stiffness, mood regulation, and quality of life (Tables 1 and 2).

Characteristics of the Acupuncture Prescriptions

One RCT4 was based on the National Acupuncture Detoxification Association protocol; 3 RCTs3,16,17 adopted the Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA); one19 used TCM textbooks; two18,24 used a manualized protocol of TCM theory; and the others referred to the published literature. The RCTs used full-body or auricular needles varying in size from 0.18 mm × 13 mm to 0.20 mm × 40 mm, and all 17 RCTs used a fixed selection of points.

The meridians and primary points involved 8 locations, including the stomach meridian (ST), Du mai (DU), spleen meridian (SP), large intestine meridian (LI), small intestine (SI), liver (LI), lung (LU), and pericardium meridian (P). In 6 RCTs,2,6,16,19,22,25 participants in the control group were administered sham acupuncture. Control group participants underwent progressive relaxation programs,7,27 no treatment, observation at baseline,3,4 normal practice including pharmacological and nonpharmacological options,5 health education,16 and waitlist control,18,22 Manual acupuncture was used in 16 RCTs2-7,15-18,21,24,26,27 and electroacupuncture in one25 (Tables 1 and 2).

Methodological Qualities of the Included Studies

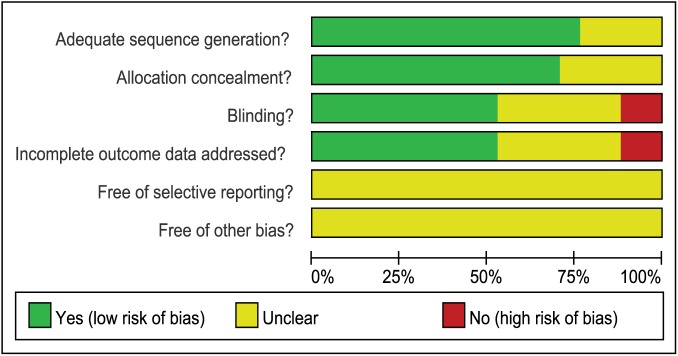

No study fulfilled all methodological criteria. Of the 17 RCTs, 10 reported adequate random sequence generation2-6,15,16,18,24; in 7, blocks were concealed and sequences were stored in sealed, opaque, numbered envelopes or used another concealed allocation protocol4,7,18,19,24,25,27; 4 adopted blinding of the patients4,16,19,24; 2 adopted blinding of the subjects and/or patients16,17; 2 reported blinding of the subjects and therapists2,25; and 1 reported blinding of the investigators, subjects, statistician, and patients.18

The remaining RCTs did not mention whether other sources of bias were present. Items assessing the Cochrane risk of bias generally demonstrated that the included RCTs demonstrated higher methodological quality involving measures of similarity between the groups at baseline and had <15% dropouts (Figure 2, Table 3).

Figure 2.

Methodological quality of included studies.

Table 3.

Methodological Quality of Included Studies.

| Author/Year | Randomization | Allocation Concealment | Blinding | Incomplete Outcome Data | Selective Outcome Reporting | Other Sources of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bao et al, 2013,2 United States | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Mention | Yes (patients, oncologist, statistician) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Crew et al, 2007,3 United States | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Mention | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Crew et al, 2010,4 United States | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Using opaque, numbered envelopes | Yes (patients) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Deng et al, 2007,15 United States | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Mention | Yes (subject, patients) | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Nedstrand et al, 2005,27 Sweden | Unclear | Using opaque, numbered envelopes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Frisk et al, 2008,23 Sweden | Randomized using random number table | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Hervik and Mjåland, 2009,21 Norway | Unclear | Using opaque, numbered envelopes | Yes (patients) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Hervik and Mjåland, 2014,22 Norway | Mention | No | Yes (patients) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Johnston et al, 2011,5 United States | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Liljegren et al, 2012,6 Sweden | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Unclear | Yes (subject) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Mao et al, 2014,18 United States (I), Europe | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Using opaque, numbered envelopes | Yes (study investigators, subject, statistician, patients) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Mao et al, 2014,24 United States (II) | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Using opaque, numbered envelopes | Yes (patients) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Mao et al, 2015,25 United States | Randomized using a computer-generated random numbers table | Using opaque, numbered envelopes | Yes (investigator, study staff, statistician | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Molassiotis et al, 2013,16 United Kingdom | Randomized using random permuted blocks | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Nedstrand et al, 2006,7 Sweden | Unclear | Using opaque, numbered envelopes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Smith et al, 2013,17 Australia | Mention | Mention | Yes (subject, patients) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Yao et al, 2016,26 Korea | Mention | No | No | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

Outcome Analysis

Compared with control therapies, the pooled results suggested that acupuncture conferred moderate effects improving stiffness and physical well-being. No significant differences were observed in hot flashes, fatigue, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, Kupperman index, general well-being, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin (IL). No adverse events were reported in any of the included trials (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect Sizes of Acupuncture Versus Control Interventions.

| Outcome | No. of Studies | No. of Patients | Standardized Mean Difference (95% CI) | Heterogeneity P Value | I 2 | Test for Overall Effect P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot flashes | 66,7,15,22,25,27 | 205 | −0.15 (−0.37, 0.06) | .19 | 32.6% | .64 |

| Fatigue | 45,16,17,24 | 177 | −0.07 (−1.04, 0.90) | .00 | 85.8% | .89 |

| Pain | 43,4,7,18 | 152 | −0.01 (−0.70, 0.72) | .00 | 78.8% | .25 |

| Stiffness | 43,4,7,26 | 112 | −0.59 (−0.92, −0.26) | .05 | 61.3% | .00 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 53,4,6,7,16 | 282 | −0.09 (−0.32, 0.15) | .72 | 0.00% | .92 |

| Kupperman index | 37,21,23 | 157 | −0.36 (−1.08, 0.37) | .01 | 74.7% | .50 |

| Physical well-being | 63,4,16,17,18,26 | 240 | −0.28 (−0.74, 0.19) | .00 | 68.9% | .42 |

| Social well-being | 33,4,16 | 176 | −0.10 (−0.40, 0.20) | .95 | 0.00% | .51 |

| Emotional well-being | 33,4,16 | 176 | 0.02 (−0.50, 0.54) | .07 | 61.4% | .93 |

| TNF | 22,3 | 64 | −0.65 (−1.83, 0.54) | .03 | 77.1% | .28 |

| IL | 22,3 | 64 | 0.15 (−1.36, 1.65) | .01 | 85% | .84 |

Abbreviations: TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin.

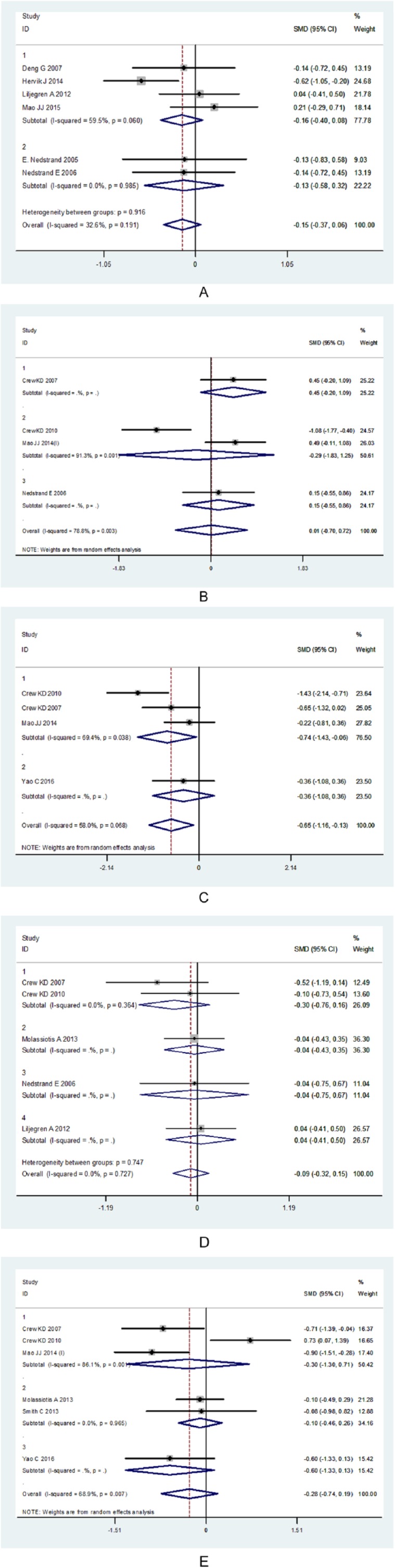

Metaregression and Subgroup Analyses

Heterogeneity was present in the comparison of studies on fatigue (I2 = 85.8%), pain (I2 = 96.1%), gastrointestinal symptoms (I2 = 81.4), Kupperman index (I2 = 72.4%), physical well-being (I2 = 73.5%), emotional well-being (I2 = 61.4%), and TNF (I2 = 77.1%) and IL (I2 = 85%) levels. Meta-regression revealed that the effects of age, clinical stage, intervention, hormone therapy, acupuncture protocol, acupuncture points, control group, indications, and duration of acupuncture practice on physical well-being and gastrointestinal symptoms did not explain the heterogeneity.

Further subgroup analyses were performed according to control groups (sham control, wait-list, relaxation, health education) with regard to hot flashes, pain, fatigue, stiffness, gastrointestinal symptoms, and physical well-being. The analyses indicated that acupuncture had potential advantages in alleviating the symptoms of stiffness; subgroup analysis of stiffness symptom demonstrated that compared with the other control group, the setting of the wait-list control group was more likely to reflect the positive effect of acupuncture (Figures 3A-3E, Table 5).

Figure 3.

A forest plot of the effects of the subgroup acupuncture therapies on treatment-related side effects: the width of the horizontal lines represent the 95% CIs of the individual studies, and the squares represent the proportional weight of each study. The diamonds represent the pooled odds ratio and 95% CI. A. Subgroups for hot flashes. B. Subgroups for pain. C. Subgroups for stiffness. D. Subgroups for gastrointestinal symptoms. E. Subgroups for physical well-being.

Abbreviation: SMD, standardized mean difference.

Table 5.

Effect Sizes of Control Subgroup Analysis.

| Outcome | No. of Studies | No. of Patients | OR [95% CI] | Heterogeneity P Value | I 2 | Test for Overall Effect P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot flashes | 46,15,22,25 (Sham control) | 456 | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.08) | .06 | 59.5% | .19 |

| 27,27 (Relaxation) | 218 | −0.13 (−0.58, 0.32) | .98 | 0% | .56 | |

| Pain | 13 (Sham control) | 18 | 0.44 (−0.19, 1.09) | 0 | 0% | .17 |

| 24,18 (Wait-list) | 78 | −0.28 (−1.82, 1.24) | 0 | 91.3% | .71 | |

| 17 (Relaxation) | 31 | 0.15 (−0.55, 0.86) | 0 | .67 | ||

| Stiffness | 33,4,7 (Wait-list) | 101 | −0.74 (−1.42, −0.05) | .03 | 69.4% | .03 |

| 126 (Diosmin) | 30 | −0.36 (−1.08, 0.36) | .06 | 58% | .32 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 23,4 (Wait-list) | 56 | −0.30 (−0.76, 0.15) | .36 | 0% | .83 |

| 16 (Sham control) | 74 | −0.04 (−0.43, 0.34) | 0 | 0% | .90 | |

| 116 (Health education) | 105 | −0.04 (−0.74, 0.66) | 0 | 0% | .84 | |

| 17 (Relaxation) | 31 | 0.04 (−0.41, 0.50) | 0 | 0% | .46 | |

| Fatigue | 216,17 (Wait-list) | 56 | 0.17 (−2.13, 2.49) | 0 | 90.9% | .88 |

| 25,24 (Health education) | 121 | −0.35 (−1.48, 0.77) | .02 | 79.1% | .53 | |

| Physical well-being | 33,4,18 (Wait-list control) | 96 | −0.29 (−1.30, 0.70) | 0 | 86.1% | .56 |

| 23,4 (Health education) | 145 | −0.09 (−0.45, 0.26) | .96 | 0% | .59 | |

| 126 (Diosmin) | 30 | −0.59 (−1.33, 0.13) | 0 | 0% | .10 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Postoperative breast cancer patients experience treatment-related side effects (fatigue, pain, stiffness, somatic dysfunction, emotional stress, and gastrointestinal symptoms) that occur together with hormone therapy–related cardiovascular events (hot flashes) and anxiety in varying degrees. Acupuncture therapy was associated with reduced risk of clinical outcomes versus placebo, based on 17 RCTs with 4 weeks to 6 months of follow-up (summarized in Table 3). Although the RCTs evaluated diverse populations, the findings were generally consistent with regard to improved stiffness of the affected limb(s).

Acupuncture protocols of the included studies varied and are a possible source of heterogeneity. These findings regarding benefits associated with acupuncture therapy were generally consistent with findings from recent RCTs that demonstrate that acupuncture has been used for postoperative treatment-related side effects and hormone therapy–related psychosomatic event management in patients who are breast cancer survivors, despite the variability in inclusion criteria, use of individual-patient data, and analytic methods.5,21,22,25,28

In contrast with the recent RCTs, the current level of evidence from a series of meta-analyses is insufficient to suggest that acupuncture is an effective treatment for postoperative treatment-related side effects and hormone therapy–related psychosomatic events in patients with breast cancer.15,29-32

Physical Parameters

The present systematic review found evidence that acupuncture could potentially relieve stiffness in the affected limb(s), whereas statistically significant differences were not found for other hormone therapy–related side effects, including hot flashes, fatigue, pain, the Kupperman index, physical well-being or gastrointestinal symptoms. Further subgroup analysis of pain, hot flashes, gastrointestinal symptoms, and physical well-being also did not show sensitivity to control settings.

The majority of acupuncture treatments administered to reduce hormone therapy–related side effects were scarcely better than a placebo.33 Previous studies have reported that acupuncture failed to manage somatic symptoms of adjuvant hormonal therapy such as hot flashes23,24,34 and fatigue.7,35,36 However, Nedstrand et al7 reached the opposite conclusion, and some RCTs reported AI-related joint symptoms improvement, reduced pain,2,3and improved Kupperman index.12,27 To date, the effect size has not been quantified, and the available evidence conveys mixed and inconclusive results. Clinical practice guidelines for CAM in breast cancer report that RCTs have shown no clear benefit of efficacy and are neither strongly positive nor negative.37

The question remains as to whether an acupuncture intervention is truly inert or if it induces physiological effects. The acupuncture points used in these RCTs were designed to reduce hormone therapy–related side effects in breast cancer patients; however, almost all acupuncture points overlap with those used to improve various other somatic symptoms; meanwhile, control group settings and individual differences in patients may partially explain the failure of the acupuncture interventions to elicit effects.

It is noteworthy that risk of bias was relatively low, and we are cautiously optimistic about the statistically significant results regarding stiffness. This analysis provides basic data regarding the power and effect size for treatment of stiffness that are needed to design an RCT, which is difficult to determine thoughtfully by standardized mean difference.

Pathological Outcomes

AI-associated musculoskeletal pain occurs in approximately 5% to 36% of breast cancer survivors undergoing treatment and can lead to treatment discontinuation.38 In postmenopausal breast cancer survivors, estrogen deprivation increases pain as well as impairs descending pain inhibitory pathways. This may be a risk factor for women undergoing AI therapy experiencing musculoskeletal disorders, including joint pain and stiffness.39

Findings from increasing evidence-based basic and clinical research suggests that pain is sensitive to acupuncture procedures. The mechanism of acupuncture was reinterpreted in an evidence-based approach in the framework of systems biology. The analgesic effect of acupuncture on chronic neuropathic pain has been shown to be mediated by P2 X3 receptors of purinergic signaling and is identified with specific neurons that are activated via stimulation of ATP flux in the brains of rat animal models.40,41 The pain mechanism of acupuncture in humans needs to be confirmed in a clinical evidence-based framework of acupuncture-induced analgesia.

In effect, a clinical study based on an RCT can be considered a reverse targeting and screening approach, designed to uncover multiple acupuncture target pathways related to cancer. In contrast to Western medicine, acupuncture puts forth a very different definition of a disease and encompasses all of the symptoms a patient presents with. Because of the highly interconnected nature of the breast cancer interactome, acupuncture is dynamic with changing boundaries, overlapping symptoms, and a multiscale nature, which makes it difficult to understand at a biological and mechanistic level. Interestingly, Henry et al42 reported that the average pain threshold at the 3-month time point was significantly lower in patients who discontinued AI therapy within 6 months. This suggests that, at least in some breast cancer patients, there may be an association between increased sensitivity to pain and impaired pain modulation before initiation of treatment; this may also be an explanation of why the pain symptoms do not show relief in this study.

Results of the present study showed that there were no significant biomarker changes in the levels of IL, in agreement with previous studies.43 Mediators of inflammation are a family of signal transducers and activators of cytokine transcription factors that play various roles in cellular processes, including immune response, apoptosis, and oncogenesis.44 However, high levels of cytokines can induce more cell migration, which is dependent on both signal transducers and activators of transcription and NF-κB (nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells), suggesting that in vivo, local inflammation caused by the growth of a tumor may result in high levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α in the tumor microenvironment, which would then lead to tumor cell migration and metastasis.45-47

Our findings suggest that acupuncture had no impact on inflammatory markers. A longer-term intervention with acupuncture may be necessary to observe some of its potential benefits. Given the effect sizes for this inflammation marker, the results should be interpreted with caution because this analysis did not have sufficient statistical power to evaluate the effects of either acupuncture or IL levels in the total sample, also considering that there were heterogeneous levels of IL at enrollment. Restrictions imposed by the small sample size limit the ability to interpret these results in a biological context. This is also a positive reminder that present consensus is gradually moving in this bioinformatics and bionetwork model through a systems biology approach to identify the relevance between cytokines/mediators of inflammation and acupuncture.

External and Internal Validity

Interventions were usually well described but of limited applicability because they often used protocols requiring the acupuncturist to select points based on past experience. No RCT mentioned how the points and needling combine. Point selection varied and focused on proving the effects of acupuncture. No RCT in our meta-analysis used an individually tailored prescription of points; only one reported a protocol in accordance with the STRICTA.15

Moreover, when using sham acupuncture (no needle insertion or very shallow insertion) as a placebo control, it is worth considering whether it is a suitable placebo intervention because of the possibility that sham acupuncture has an active effect related to peripheral sensory stimulation, making it difficult to fix specific points on the body to eliminate the placebo effect. Unfortunately, acupuncture prescriptions are still unstandardized.

Patients were, therefore, not treated optimally according to TCM principles. Future studies should investigate point selection in accordance with TCM theory as opposed to a set point prescription. Moreover, designs should address blinding the therapist to the treatment because double-blinding is a significant problem in acupuncture trials. In one RCT, patients were given antidepressants as supplements to help them cope with menopausal symptoms (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor).15

Potential Biases in the Review Process

The small number of RCTs may have caused the lack of statistical significance. Although the results were adjusted for a wide range of covariates, the possibility of heterogeneity still exists. Residual confounding factors, including the characteristics of the acupuncture prescription, age at diagnosis, disease stage and severity, frequency, duration of the intervention for treatment-related side effects, indications for acupuncture, hormone prescription, lifestyle factors, and self-reported quality of life could not be completely excluded, and the findings thus could not result in a reasonable recommendation.

All the included studies analyzed the settings of the control group, which indicated the significance of the control group in each study. In one RCT, control patients were given diosmin (900 mg tablets, orally 3 times daily) to help them cope with symptoms of lymphedema,26 which led to a bias in determining a specific therapeutic effect of acupuncture because of inadequate control for nonspecific effects among breast cancer patients. Subgroup analysis revealed that effects on acupuncture outcomes are sensitive to the type of control group. The estimation of the effect size for control groups in the RCTs reinforced the lesson that when there is an imbalance in the baseline of control participants, results may be unstable, masked, or amplified. Each RCT used a different study design and implemented control groups differently. Choice of the control group was far more important than acupuncture protocols as a determinant of outcome in some ways: this deficiency was itself partly a result of the design of control groups.

We did not find statistically significant differences in hormone therapy–related outcome indicators between the control subgroups (sham, wait-list, relaxation, drug group, and health education) and real acupuncture groups. Subgroup analysis was not sensitive to the influence of the outcome indicators. Despite this, the nonsignificant findings may also have occurred because sham/minimal acupuncture is not inert, with real acupuncture and sham/minimal acupuncture shown to induce a significant physiological response in a recent study.48

Any type of physiological stimulus, including tactile, is capable of stimulating multimodal receptors of C-fiber primary afferents that can modulate the limbic system and, thus, reduce the affective components of pain.49 RCTs that used sham acupuncture controls suggest that sham acupuncture may be as effective as real acupuncture; based on the small sample size, evidence-based well-designed trials are still needed to confirm these findings.

In conclusion, hormone therapy–related side effects remain a major component of the symptom burden in breast cancer patients, and many oncologists discontinue aromatase-inhibitor therapies, so that their patients will experience reductions in symptoms and regain quality of life. Borderline evidence suggests that acupuncture may be safe and effective for managing joint stiffness; however, the small sample sizes and risk of bias limit the interpretation of the results. Our findings add to the small but growing body of literature suggesting that acupuncture may not have clinical benefits in reducing common hormone therapy–related side effects with respect to psychosomatic symptoms and quality of life.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We are indebted to the following education and research institutions for financial support. (1) Key Project of the 2017 year, Vocational Technical Education Branch of Higher Education Research Academy of China: Research on the Path of the Application of Evidence-based Medical Education and Knowledge Transformation in Higher Medical Vocational Education (Grant No: GZYZD2017012). (2) Key Project of the 2017 year, Tianjin Higher Vocational and Technical Education Research Institute: the International Standard and Path Study on the Advanced Training of JBI Health Care Model for Higher Medical Vocational Education (Grant No: 106). (3) Lanzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau of Gansu province of China of Science and Technology Project (medical and health special): Applicability Evaluation of Systematic Review of Breast Cancer Treated with Non Drug Complementary Alternative Medicine (Grant No: 2016-2-68).

References

- 1. Mouridsen HT. Incidence and management of side effects associated with aromatase inhibitors in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1609-1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bao T, Cai L, Giles JT, et al. A dual-center randomized controlled double blind trial assessing the effect of acupuncture in reducing musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer patients taking aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:167-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crew KD, Capodice JL, Greenlee H, et al. Pilot study of acupuncture for the treatment of joint symptoms related to adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:283-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crew KD, Capodice JL, Greenlee H, et al. Randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for the management of aromatase inhibitor-associated joint symptoms in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1154-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnston MF, Hays RD, Subramanian SK, et al. Patient education integrated with acupuncture for relief of cancer-related fatigue randomized controlled feasibility study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liljegren JA, Gunnarsson P, Landgren BM, et al. Reducing vasomotor symptoms with acupuncture in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:791-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nedstrand E, Wyon Y, Hammar M, Wijma K. Psychological well-being improves in women with breast cancer after treatment with applied relaxation or electro-acupuncture for vasomotor symptom. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;27:193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Metcalfe A, Williams J, McChesney J, Patten SB, Jette N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by those with a chronic disease and the general population—results of a national population based survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mao JJ, Palmer CS, Healy KE, Desai K, Amsterdam J. Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer survivors: a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jia L. Cancer complementary and alternative medicine research at the US National Cancer Institute. Chin J Integr Med. 2012;18:325-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ernst E. Assessments of complementary and alternative medicine: the clinical guidelines from NICE. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1350-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chao LF, Zhang AL, Liu HE, Cheng MH, Lam HB, Lo SK. The efficacy of acupoint stimulation for the management of therapy-related adverse events in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:255-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kraft K. Complementary/alternative Medicine in the context of prevention of disease and maintenance of health. Prev Med. 2009;49:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Halsey EJ, Xing M, Stockley RC. Acupuncture for joint symptoms related to aromatase inhibitor therapy in postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: a narrative review. Acupunct Med. 2015;33:188-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deng G, Vickers A, Yeung S, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of acupuncture for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5584-5590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Molassiotis A, Bardy J, Finnegan-John J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acupuncture self-needling as maintenance therapy for cancer-related fatigue after therapist-delivered acupuncture. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1645-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith C, Carmady B, Thornton C, Perz J, Ussher JM. The effect of acupuncture on post-cancer fatigue and well-being for women recovering from breast cancer: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2013;31:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mao JJ, Xie SX, Farrar JT, et al. A randomised trial of electro-acupuncture for arthralgia related to aromatase inhibitor use. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:267-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chandler J, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Davenport C, Clarke MJ. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. http://community.cochrane.org/book_pdf/764. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- 20. Healey JF. Statistics: A Tool for Social Research. 10th ed. College Station, TX: Stata Corp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hervik J, Mjåland O. Acupuncture for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients, a randomized, controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:311-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hervik J, Mjåland O. Long term follow up of breast cancer patients treated with acupuncture for hot flashes. Springerplus. 2014;3:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frisk FJ, Carlhäll S, Källström AC, Lindh-Astrand L, Malmström A, Hammar M. Long-term follow-up of acupuncture and hormone therapy on hot flushes in women with breast cancer: a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter trial. Climacteric. 2008;11:166-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Bruner D, et al. Electroacupuncture for fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia: a randomized trial. Cancer. 2014;120:3744-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Xie SX, Bruner D, DeMichele A, Farrar JT. Electroacupuncture versus gabapentin for hot flashes among breast cancer survivors: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3615-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yao C, Xu Y, Chen L, et al. Effects of warm acupuncture on breast cancer-related chronic lymphedema: a randomized controlled trial. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:e27-e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nedstrand E, Wijma K, Wyon Y, Hammar M. Vasomotor symptoms decrease in women with breast cancer randomized to treatment with applied relaxation or electro-acupuncture: a preliminary study. Climacteric. 2005;8:243-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Molassiotis A, Sylt P, Diggins H. The management of cancer-related fatigue after chemotherapy with acupuncture and acupressure: a randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15:228-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee MS, Kim KH, Choi SM, Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating hot flashes in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salehi A, Marzban M, Zadeh AR. Acupuncture for treating hot flashes in breast cancer patients: an updated meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4895-4899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johns C, Seav SM, Dominick SA, et al. Informing hot flash treatment decisions for breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of randomized trials comparing active interventions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;156:415-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garcia MK, Graham-Getty L, Haddad R, et al. Systematic review of acupuncture to control hot flashes in cancer patients. Cancer. 2015;121:3948-3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeong YJ, Park YS, Kwon HJ, Shin IH, Bong JG, Park SH. Acupuncture for the treatment of hot flashes in patients with breast cancer receiving antiestrogen therapy: a pilot study in Korean women. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:690-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen YP, Liu T, Peng YY, et al. Acupuncture for hot flashes in women with breast cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12:535-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang S, Mu W, Xiao L, et al. Is deqi an indicator of clinical efficacy of acupuncture? A systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:750140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liao GS, Apaya MK, Shyur LF. Herbal medicine and acupuncture for breast cancer palliative care and adjuvant therapy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:437948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nahleh Z, Tabbara IA. Complementary and alternative medicine in breast cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2003;1:267-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brown JC, Mao JJ, Stricker C, Hwang WT, Tan KS, Schmitz KH. Aromatase inhibitor associated musculoskeletal symptoms are associated with reduced physical activity among breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2014;20:22-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baum M, Buzdar A, Cuzick J, et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination) trial efficacy and safety update analyses. Cancer. 2003;98:1802-1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tang Y, Yin HY, Rubini P, Illes P. Acupuncture-induced analgesia: a neurobiological basis in purinergic signaling. Neuroscientist. 2016;22:563-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barragán-Iglesias P, Mendoza-Garcés L, Pineda-Farias JB, et al. Participation of peripheral P2Y1, P2Y6 and P2Y11 receptors in formalin-induced inflammatory pain in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;128:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Henry NL, Conlon A, Kidwell KM, et al. Effect of estrogen depletion on pain sensitivity in aromatase inhibitor-treated women with early-stage breast cancer. J Pain. 2014;15:468-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Arnedos M, Drury S, Afentakis M, et al. Biomarker changes associated with the development of resistance to aromatase inhibitors (AIs) in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:605-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ben-Neriah Y, Karin M. Inflammation meets cancer, with NF-κB as the matchmaker. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:715-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Snyder M, Huang J, Huang XY, Zhang JJ. A signal transducer and activator of transcription 3·nuclear factor κB (Stat3·NFκB) complex is necessary for the expression of fascin in metastatic breast cancer cells in response to interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:30082-30089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tripsianis G, Papadopoulou E, Anagnostopoulos K, et al. Coexpression of IL-6 and TNF-α: prognostic significance on breast cancer outcome. Neoplasma. 2014;61:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tripsianis G, Papadopoulou E, Romanidis K, et al. Overall survival and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with breast cancer in relation to the expression pattern of HER-2, IL-6, TNF-α and TGF-β1. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:6813-6820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lundeberg T, Lund I, Sing A, Näslund J. Is placebo acupuncture what it is intended to be? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:932407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hui KK, Liu J, Marina O, et al. The integrated response of the human cerebro-cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;27:479-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]