Abstract

Nausea and vomiting are among the most common and distressing side effects of chemotherapy. Additional antiemetic drugs are urgently needed to effectively manage and ameliorate chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV). The efficacy of ginger as an antiemetic modality for ameliorating CINV has not been established in previous studies. The aim of this study was to examine the efficacy of ginger, as an adjuvant drug to standard antiemetic therapy, in ameliorating acute and delayed CINV in patients with lung cancer receiving cisplatin-based regimens. In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, 140 patients with lung cancer receiving cisplatin-based regimens were enrolled and allocated to receive either ginger root powder or a placebo. Ginger root powder was administered orally (0.5 g, 2 capsules per day, 0.25 g per capsule, every 12 hours) for 5 days beginning on the first day of chemotherapy. The incidence and severity of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting were assessed using the MASCC (Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer) Antiemesis Tool (MAT). Adverse effects and patient adherence were also assessed in this study. No significant difference was observed between the ginger and control groups in the reduction of the incidence and severity of nausea and vomiting (P > .05). No significant difference in adverse events was observed between the 2 groups (P > .05). No study-treatment-related adverse events were observed in this study. As an adjuvant drug to standard antiemetic therapy, ginger had no additional efficacy in ameliorating CINV in patients with lung cancer receiving cisplatin-based regimens.

Keywords: chemotherapy, nausea, vomiting, cisplatin, ginger, lung cancer

Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is among the most common and distressing side effects of chemotherapy. Acute CINV occurs within the first 24 hours after chemotherapy, whereas delayed CINV occurs after 24 hours and up to 5 days after chemotherapy.1 It is estimated that 36% to 62% of patients experience nausea during the delayed phase, even with concurrent use of antiemetic drugs such as combinations of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (RAs), neurokinin-1 Ras, and dexamethasone.2-4 Cisplatin, which is a cornerstone of chemotherapy for the treatment of multiple cancers, is a highly emetogenic chemotherapy drug.5 High-dose cisplatin induces vomiting in all patients during the 24 hours after the administration unless antiemetic drugs are used.6 Even with the guideline-recommended antiemetic drugs, cisplatin-induced vomiting is controlled in only 60% of patients; therefore, considerable numbers of patients still experience nausea.7 CINV has also been shown to significantly affect the quality of life (QoL) and daily function of patients receiving chemotherapy.8 Moreover, CINV is so severe in some cases that it interrupts the treatment of primary cancer and increases the risk of disease progression.9,10

Ginger (Zingiber officinale), an ancient spice, is most notably known as a flavoring agent for food in Asian recipes.11 Modern studies have confirmed that ginger might be effective in ameliorating nausea and vomiting induced by motion sickness, sea sickness, pregnancy, and postoperative sickness.12 Previous studies have found that ginger contains a wide array of bioactive compounds (particularly gingerol and shogaol) that can act on multiple pathways involved in the physiology of CINV. The properties include 5-HT3 receptor, substance P, and acetylcholine receptor antagonism; anti-inflammatory properties; and modulation of cellular redox signaling, vasopressin release, gastrointestinal motility, and gastric emptying rate.13 However, clinical trials on the efficacy of ginger in ameliorating CINV have yielded both positive and negative results.14,15

A recent meta-analysis consisting of randomized, controlled trials with a total of 872 patients with cancer did not support the efficacy of ginger in ameliorating CINV.12 These trials exhibited significant differences in primary cancers, chemotherapy regimens, ginger dosages, and assessment methods. Multiple factors may influence the risk of developing CINV, including the treatment protocol, the patient’s lifestyle, and previous experience with nausea and vomiting.16 To better understand the efficacy of ginger in ameliorating CINV, this study controlled for the primary cancer, the chemotherapy regimen, antiemetic use, the dose of ginger administered, and the duration of ginger treatment. Furthermore, lifestyle factors such as alcohol intake and previous experience of motion sickness/morning sickness have been shown to influence CINV risk.16 Therefore, these factors were assessed in this study. Previous studies have suggested that future trials should be performed with low-dose ginger (0.5 g per day).1 Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine the efficacy of ginger in ameliorating acute and delayed CINV among patients with lung cancer receiving cisplatin-based regimens.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Considerations

This study was performed with the approval of the Peking Union Medical College Hospital Ethics Committee in accordance with medical ethics standards. Recruiters at each ward identified eligible patients from medical records. Once identified, the recruiter met with eligible patients, presented the study to potential subjects, and invited them to participate in the research. The consent forms were signed, and the enrollment form was completed by the recruiter for patients who were willing to participate. Participants were monitored for adverse effects, and the trial was discontinued immediately if the study was determined to be causing harm or if participants chose to withdraw.

Participants

Participants were recruited from 3 cancer wards at Peking Union Medical College Hospital from June 2016 to March 2017. The inclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) an age of at least 18 years, (2) a diagnosis of lung cancer, (3) patients receiving cisplatin-based regimens, (4) patients receiving standard antiemetic therapy (5-HT3 RAs), (5) the ability to swallow capsules, and (6) nonuse of self-prescribed therapies or complementary products. The exclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) an allergy to ginger, (2) pregnancy or lactation, (3) current radiotherapy, (4) preexisting nausea or vomiting from any cause, (5) the presence of other diseases as a possible cause of nausea or vomiting (hepatitis, gastrointestinal obstruction, or diseases), (6) use of coumadin or heparin for therapeutic anticoagulation, and (7) blood disorders or a platelet count <100 000/µL.

Methodology and Design

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, 146 patients with lung cancer were enrolled and allocated to the placebo group (n = 73) or the ginger group (n = 73). Patients received the first dose of the study medication 30 minutes before chemotherapy on the first day of treatment. Ginger capsules and the placebo were administered orally (0.5 g, 2 capsules per day, 0.25 g per capsule, every 12 hours) for 5 days beginning on the first day of chemotherapy. Each ginger capsule contained 250 mg of dry ginger powder. The ginger powder we used in the study was a commercial ginger extract manufactured by Shanxi Sciphar Natural Products Co, Ltd, Shaanxi, China. The ginger powder was standardized to contain 5% gingerols. The placebo capsules were physically identical to the ginger capsules and contained 250 mg of corn starch.

Sample Size Determination

Using the χ2 test, the incidence of CINV (primary outcome) was compared with the reduction in the incidence of CINV reported by Panahi et al,17 P1 (incidence of CINV in the ginger group) = .351; P2 (incidence of CINV in the control group) = .585. The smaller of these values is .351, and the difference is .234. Sixty-six participants were needed in each group to detect a difference with 80% power at the 5% significance level (2-tailed). Considering a 10% dropout rate, the number of participants was adjusted to 146.

Instruments and Measures

Patient characteristics (Table 1) were collected by self-report and confirmed in the medical record by the recruiters. The incidence and severity of CINV were measured using the MASCC (Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer) Antiemesis Tool (MAT) 8-item short-form (Chinese) with a Cronbach α greater than .71.18 Four items referred to the incidence, duration, and frequency of acute nausea and vomiting, and the other items referred to delayed nausea and vomiting. The items were not summed, and all items were evaluated individually in clinical practice. Dichotomous items were scored as 0 (No) or 1 (Yes), and continuous variables were scored on scales of 0 to 10. The MAT is a reliable and valid clinical tool. Delayed CINV data were obtained by phone contact on the fifth day after chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Main Concepts, Measures, and Collection Schedule.

| Concepts | Measures | Schedule |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Self-report confirmed by the recruiters | Day 1 |

| Cancer | Diagnosed by oncologists and confirmed by the recruiters | Day 1 |

| Incidence and severity of acute CINV | MAT | Day 2 |

| Incidence and severity of delayed CINV | MAT | Day 5 |

| Patient adherence | Self-report confirmed by the investigators | Day 5 |

| Adverse effects | Self-report | Anytime |

| QoL | FACT-G | Day 1 and day 5 |

Abbreviations: CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; MAT, MASCC Antiemesis Tool; QoL, quality of life; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General.

Patient adherence was determined by face-to-face and phone interviews and measured with a questionnaire developed for patients to record if and when they consumed the ginger or placebo on each day. Patients were asked to perform a pill count and report the number by phone interview at each time of contact. Adverse effects were collected by verbal self-report and pertained to any adverse events that occurred during the 5 days. At the end of the fifth day, the investigators contacted each participant to obtain information regarding blinding and assessed the blinding by asking each participant the following questions: Do you think that you received placebo or ginger, and why do you think so?

The participants’ QoL was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General questionnaire, a widely used validated tool.19 It contains 27 questions recorded using a 5-point scale and assesses 4 domains of patient QoL: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well-being. It was obtained at baseline and on day 5.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 20.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chinese). Baseline characteristics are reported as means and standard deviations or as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and as counts and percentages for categorical variables. Baseline characteristics, QoL, and severity of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting were compared between the 2 groups using independent samples t/nonparametric tests for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2/Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Incidence of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting was calculated as a binary variable (“yes” if participants had nausea or vomiting or “no” if participants had no nausea or vomiting) and was compared with a Pearson χ2 test. A similar analysis was used to examine the adverse effects.

Two-tailed tests with a significance level of .05 were used for all analyses. The per protocol (completer) approach was used for data analysis. The reason for not performing intent-to-treat analysis was lack of access to the posttrial data of patients who discontinued the study because they did not complete their questionnaires.

Validity and Reliability

The randomization list was created using EpiCalc 2000 by a researcher who had no contact with participants. The assignments were inserted in sequentially numbered envelopes. When a new participant was to be randomized, the researcher took the next envelope and assigned the person to 1 of 2 groups accordingly. This procedure guaranteed that group assignment was not affected by the investigators and was concealed until the moment of randomization. In addition, all capsules were completely identical in appearance, contour, size, and color in this study.

Results

Patient Characteristics

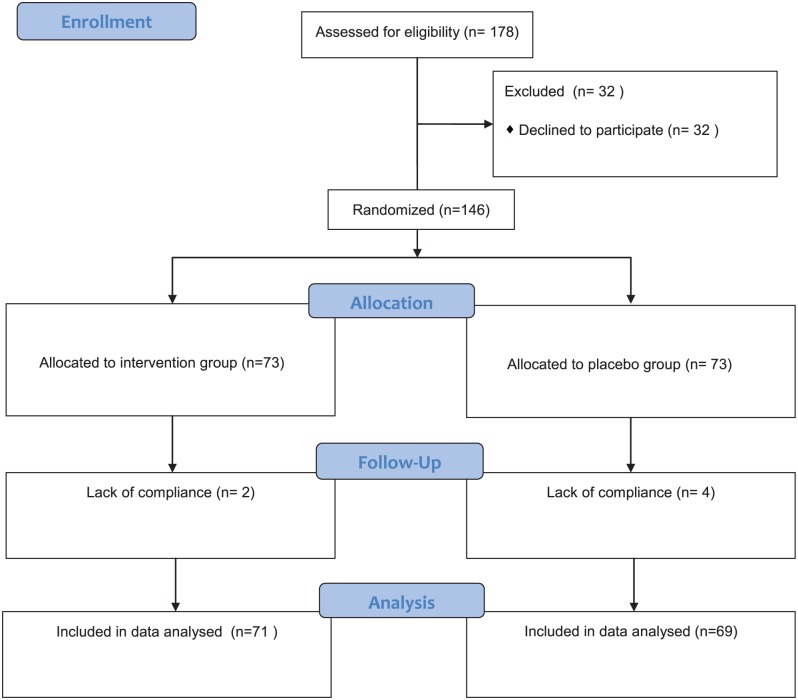

Figure 1 shows the patient flow in this randomized controlled trial. Of 146 participants, 140 participants completed the trial (71 in the ginger group and 69 in the placebo group). The reason for leaving the study was lack of compliance, which was based on the self-report. The dropout rate was not significantly different between the 2 groups (P = .677, χ2 = 0.174). No significant difference between the 2 groups was noted in the demographic data, clinical data, or CINV susceptibility at baseline (Table 2). All participants received ≥1 chemotherapy cycle, and 92 participants (65.7%) received aprepitant.

Figure1.

Flow diagram of trial for the 2 groups.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Participants in the 2 Groups.

| Characteristics | Placebo (n = 69) | Ginger (n = 71) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 47 (68.12) | 53 (74.65) | .392 |

| Female | 22 (31.88) | 18 (25.35) | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 57.46 (7.82) | 57.52 (7.24) | .964 |

| Alcohol intake (days per week) | 2 (0, 4) | 2 (0, 3) | .801 |

| Ginger seasoning use (days per week) | 3 (2, 7) | 3 (0, 7) | .458 |

| Chemotherapy regimens, n (%) | |||

| Cisplatin | 43 (62.32) | 53 (74.65) | .226 |

| Carboplatin | 21 (30.43) | 16 (22.53) | |

| Oxaliplatin | 5 (7.25) | 2 (2.82) | |

| Aprepitant, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 44 (63.77) | 48 (67.61) | .632 |

| No | 25 (36.23) | 23 (32.39) | |

| Susceptibility to motion sickness, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 21 (30.43) | 18 (25.35) | .502 |

| No | 48 (69.57) | 53 (74.65) | |

| Susceptibility to morning sickness, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 16 (72.73) | 11 (61.11) | .435 |

| No | 6 (27.27) | 7 (38.89) | |

| Experienced CINV in previous cycles | |||

| Yes | 41(59.42) | 47 (66.20) | .41 |

| No | 28 (40.58) | 24 (33.80) | |

| Quality of life (FACT-G), mean (SD) | 71.78 (14.68) | 72.65 (14.00) | .72 |

Abbreviations: CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General.

Patient Adherence and Adverse Effects

Of 140 participants, 135 participants (96.4%) used the study drugs according to the study protocol, and 5 participants used 6 to 8 of the 10 capsules in the placebo group (based on the self-report).

No significant difference was observed in the incidence of adverse events between the 2 groups (Table 3). No study-treatment-related adverse event was observed in this study.

Table 3.

Adverse Events of the Participants in the 2 Groups.

| Adverse Events | Placebo (n = 69), n (%) | Ginger (n = 71), n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drowsiness | 21 (30.4) | 30 (42.2) | .163 |

| Dry mouth | 9 (13.0) | 18 (25.4) | .086 |

| Heartburn | 3 (4.35) | 6 (8.45) | .494 |

| Flushing | 5 (7.2) | 11 (15.5) | .184 |

Incidence and Severity of Acute Nausea and Vomiting

Eighty-eight participants (62.9%) had acute nausea, and 17 participants (12.1%) had acute vomiting.

Forty-nine participants (69.0%) in the ginger group and 39 participants (56.5%) in the placebo group had acute nausea, resulting in no significant difference in the incidence of acute nausea between the 2 groups (P = .174). Six participants (8.5%) in the ginger group and 11 participants (15.9%) in the placebo group had acute vomiting, resulting in no significant difference in the incidence of acute nausea between the 2 groups (P = .309).

The median nausea scores (P = .246) and vomiting frequencies (P = .256) of participants with acute nausea were not significantly different between the 2 groups. Ninety-two participants received aprepitant for treatment of CINV, and participants were stratified by whether aprepitant was used. No significant difference in the incidence and severity of nausea and vomiting was observed between the 2 groups (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Incidence and Severity of Acute and Delayed Nausea and Vomiting in the 2 Groups.

| Incidence | Placebo (n = 69), n (%) | Ginger (n = 71), n (%) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute nausea | |||

| Without aprepitant | 14 (20.3) | 17 (23.9) | .174 |

| With aprepitant | 25 (36.2) | 32 (45.1) | |

| Delayed nausea | |||

| Without aprepitant | 30 (43.5) | 26 (36.6) | .214 |

| With aprepitant | 20 (29.0) | 17 (23.9) | |

| Acute vomiting | |||

| Without aprepitant | 4 (5.8) | 4 (5.6) | .309 |

| With aprepitant | 7 (10.1) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Delayed vomiting | |||

| Without aprepitant | 6 (8.7) | 9 (12.7) | .813 |

| With aprepitant | 12 (17.4) | 7 (9.9) | |

P-values were calculated using Cochran Mantel-Haenszel tests stratified by aprepitant use.

Table 5.

Incidence and Severity of Acute and Delayed Nausea and Vomiting in the 2 Groups.

| Severity | Placebo Group (n = 69) | Ginger Group (n = 71) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea scores | |||

| Acute | 3 (0, 4) | 3 (0, 4) | .246 |

| Delayed | 2 (0, 4.5) | 1 (0, 5) | .347 |

| Vomiting frequencies | |||

| Acute | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | .256 |

| Delayed | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | .718 |

Incidence and Severity of Delayed Nausea and Vomiting

Ninety-three participants (66.4%) had delayed nausea, and 34 participants (24.3%) had delayed vomiting.

Fifty participants (72.5%) in the placebo group and 43 participants (60.6%) in the ginger group had delayed nausea, resulting in no significant difference in the incidence of delayed nausea between the 2 groups (P = .214). Eighteen participants (26.1%) in the placebo group and 16 participants (22.5%) in the ginger group had delayed vomiting, resulting in no significant difference in the incidence of delayed vomiting between the 2 groups (P = .813).

The median (interquartile range) nausea scores of participants with delayed nausea were 2 (0, 4.5) in the placebo group and 1 (0, 5) in the ginger group. The median (interquartile range) vomiting frequencies of participants with delayed nausea were 0 (0, 1) in the placebo group and 0 (0, 0) in the ginger group. The median nausea scores (P = .347) and vomiting frequencies (P = .718) were not significantly different between the 2 groups (Tables 4 and 5).

Ginger Effects on Quality of Life

The mean QoL score was 72.45 ± 13.93 in the placebo group and 72.79 ± 14.00 in the ginger group. No significant difference was observed in QoL between the 2 groups (P = .884).

Assessment of Blinding

At the end of the fifth day, all participants were asked one question: Which treatment do you think you received? Participants were likely to correctly guess the treatment that they received (P = .01). The taste of ginger root powder in the capsules was a common reason given for knowing which treatment they received (placebo group: 27.5%; ginger group: 42.3%; P = .068). “The way the capsules worked” was the second reason for knowing which treatment participants received (placebo group: 10.1%; ginger group: 21.1%; P = .103). Some participants reported that they felt a warm sensation in their stomach after receiving the capsules.

Discussion

Previous studies have analyzed the possible efficacy of ginger in ameliorating CINV. However, some studies have supported this efficacy, while other studies have shown the opposite results.20-24 The reason for these inconsistent results might be that these studies have multiple methodological limitations that must be addressed before this intervention can be recommended as a complement to routine clinical practice. The limitations include the lack of control for predisposing factors, nonhomogeneity of ginger dose, and inconsistent use of validated questionnaires and standardized ginger products.16 The current study was designed to overcome these limitations.

This study has overcome limitations identified in previous studies by including the use of validated assessment tools, a standardized ginger extract, and a recommended ginger dosage, as well as the assessment of previously identified prognostic factors such as age, gender, alcohol use, and so on. Furthermore, we assessed the ginger seasoning use since ginger had a widespread use as a spice and flavoring agent in China. The daily dose of ginger varied from 0.5 to 3.5 g, and the treatment duration ranged from 1 to 6 days.12 However, some studies have suggested that a daily ginger dose of 1 g has no effect on ameliorating acute nausea and vomiting, and a daily dose of 2 g increases the severity of nausea.20,21 Therefore, this study used a low dose of ginger (0.5 g per day).1 In addition, this study was performed in patients with a diagnosis of lung cancer who were receiving cisplatin-based regimens to eliminate the effect of primary cancers and chemotherapy regimens. This study showed that compared with the placebo, ginger had no additional efficacy on ameliorating nausea and vomiting in patients with lung cancer receiving cisplatin-based regimens.

The poor efficacy of ginger in ameliorating nausea and vomiting in this study might be due to several factors. Patients who suffered from CINV during previous treatments were more likely to participate in this study. After repeatedly failing to ameliorate CINV, these patients would seek other treatments. Therefore, patient compliance was high in this study. Meanwhile, all participants also received ondansetron and dexamethasone, and 65.7% of participants also used aprepitant. Regarding antinausea measurement, a decrease in the incidence of CINV is not obvious and may have been missed in our study. However, the interaction with other drugs may weaken the effect of ginger powder. Zick et al20 suggested that ginger increased the severity of delayed nausea when co-administered with aprepitant, and participants receiving aprepitant and ginger had a consistently higher incidence of both acute and delayed nausea. Ginger might decrease gastrointestinal absorption and the antinausea efficacy of aprepitant by increasing intestinal motility and shortening gastric emptying time.20 The inability to produce an obvious difference in QoL could be due to the inability to control delayed nausea and vomiting. A reduction in delayed CINV would improve patient QoL during chemotherapy.1

Limitations

One limitation of this study was the difficulty in blinding participants to the specific drugs that they received. Although all capsules were identical in appearance, contour, size, and color in this study, a difference in smell could be observed between the ginger and corn starch if participants opened capsules. To minimize the bias, each participant was contacted to obtain information regarding the study blinding after the study concluded. The second limitation was the possible effect of the ginger seasoning. Ginger is one of the most commonly used seasoning agents in China. In order to minimize the bias, we assessed the ginger seasoning use while other lifestyle factors (such as alcohol use) were assessed. Amounts of ginger seasoning used in this study were very limited. In the future study, large amounts of dietary ginger should be stopped at least 1 week prior to chemotherapy.16

Another limitation was not controlling for the chemotherapy cycle. Recent research has demonstrated that anticipatory nausea contributes to the reporting of acute nausea. Patients were more likely to experience CINV if CINV is experienced during an earlier cycle.1 However, randomization procedures decreased the bias in this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that use of ginger as an adjuvant drug to standard antiemetic therapy produced no additional efficacy in ameliorating the incidence and severity of CINV in patients with lung cancer receiving cisplatin-based regimens.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Kala Mehta from the University of California, San Francisco, for guidance with the study design.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This trial has also been registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (http://www.chictr.org.cn) and was assigned the identifier: ChiCTR-IOR-16008633.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

References

- 1. Ryan JL, Heckler CE, Roscoe JA, et al. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces acute chemotherapy-induced nausea: a URCC CCOP study of 576 patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1479-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aapro M, Fabi A, Nolé F, et al. Double-blind, randomised, controlled study of the efficacy and tolerability of palonosetron plus dexamethasone for 1 day with or without dexamethasone on days 2 and 3 in the prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1083-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Celio L, Frustaci S, Denaro A, et al. ; Italian Trials in Medical Oncology Group. Palonosetron in combination with 1-day versus 3-day dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1217-1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Navari RM, Gray SE, Kerr AC. Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized phase III trial. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:188-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen L, de Moor CA, Eisenberg P, Ming EE, Hu H. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: incidence and impact on patient quality of life at community oncology settings. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gralla RJ, Itri LM, Pisko SE, et al. Antiemetic efficacy of high-dose metoclopramide: randomised trial with placebo and prochlorperazine in patients with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:905-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bloechl-Daum B, Deuson RR, Mavros P, Hansen M, Herrstedt J. Delayed nausea and vomiting continue to reduce patients’ quality of life after highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy despite antiemetic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4472-4478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Navari RM. Management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: focus on newer agents and new uses for older agents. Drugs. 2013;73:249-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ballatori E, Roila F, Ruggeri B, et al. The impact of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on health-related quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vidall C, Dielenseger P, Farrell C, et al. Evidence-based management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a position statement from a European cancer nursing forum. Ecancermedicalscience. 2011;5:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shukla Y, Singh M. Cancer preventive properties of ginger: a brief review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:683-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee J, Oh H. Ginger as an antiemetic modality for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:163-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marx W, Ried K, McCarthy AL, et al. Ginger—mechanism of action in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marx WM, Teleni L, McCarthy AL, et al. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic literature review. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jordan K, Gralla R, Jahn F, Molassiotis A. International antiemetic guidelines on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): content and implementation in daily routine practice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;722:197-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marx W, McCarthy AL, Ried K, et al. Can ginger ameliorate chemotherapy-induced nausea? Protocol of a randomized double blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Panahi Y, Saadat A, Sahebkar A, Hashemian F, Taghikhani M, Abolhasani E. Effect of ginger on acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a pilot, randomized, open-label clinical trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:204-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brearley SG, Clements CV, Molassiotis A. A review of patient self-report tools for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1213-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cella D, Hahn EA, Dineen K. Meaningful change in cancer specific quality of life scores: differences between improvement and worsening. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:207-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zick SM, Ruffin MT, Lee J, et al. Phase II trial of encapsulated ginger as a treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:563-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manusirivithaya S, Sripramote M, Tangjitgamol S, et al. Antiemetic effect of ginger in gynecologic oncology patients receiving cisplatin. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:1063-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sontakke S, Thawani V, Naik MS. Ginger as an antiemetic in nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy: a randomized, cross-over, double blind study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2003;35:32-36. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thamlikitkul L, Srimuninnimit V, Akewanlop C, et al. Efficacy of ginger for prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in breast cancer patients receiving adriamycin-cyclophosphamide regimen: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:459-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fahimi F, Khodadad K, Amini S, Naghibi F, Salamzadeh J, Baniasadi S. Evaluating the effect of Zingiber officinalis on nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cisplatin based regimens. Iran J Pharm Res. 2011;10:379-384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]