Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a societal problem with many repercussions for the health care and judicial systems. In the United States, women of color are frequently affected by IPV and experience negative, physical, and mental ramifications. Increasing IPV perpetration and perpetration recurrence rates among men of Mexican origin (MMO) warrants a better understanding of unique risk factors that can only be described by these men. Qualitative studies regarding MMO and distinct IPV risk factors among this populace are few and infrequent. The purpose of this study was to describe IPV risk factors among men of MMO and to describe the process by which these men are able to overcome IPV perpetration risk factors. Fifty-six men of Mexican origin from a low-income housing community in far-west Texas were recruited for participation in audiotaped focus groups. Grounded theory (GT) methodology techniques were utilized to analyze, translate, and transcribe focus group data. Data collection ended when saturation occurred. Participants described risk factors for IPV. Emerging themes included: environment as a context, societal view of MMO, family of origin, normalcy, male and female contributing factors to IPV, and breaking through. Theme abstractions led to the midrange theory of Change Through Inspired Self-Reflection which describes the process of how MMO move from IPV perpetration to nonviolence. The results of the study provide insight on what MMO believe are IPV risk factors. There are implications for clinicians who provide services to MMO, and provide the impetus for future research among this population.

Keywords: Mexican American, culture, Machismo, qualitative methods

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as mental, physical, or sexual violence that transpires in relationships of an intimate nature (Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, & Mahendra, 2015). Intimate partner violence has no ethnic, socioeconomic or cultural boundaries; however, some populations are affected more so than others (González-Guarda, Peragallo, Vasquez, Urrutia, & Mitrani, 2009; Johnson, 2008). Each year in the United States, it is estimated that 29 million women experience some form of abuse caused by a current spouse or intimate partner (Breidling, Smith, Baslie, Walters, Chen, & Merrick, 2011). Intimate partner violence is not only physically, sexually, and psychologically harmful to women (World Health Organization, 2014). The long-term medical and/or psychological treatments (Rivara et al., 2007) have a negative impact on the health-care system. The yearly burden on the U.S. economy caused by IPV-related injuries is conservatively estimated around $5.8 billion due to medical and mental health expenses, and does not include associated legal system expenses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003; Max, Rice, Finkelstein, Bardwell, & Leadbetter, 2004). In addition, the economic devastation caused by IPV in terms of workplace productivity is estimated to be $1.8 billion and equals almost 32,000 jobs or 8 million paid work days (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003).

Intimate partner violence also has behavioral (Sternberg, Baradaran, Abbott, Lamb, & Guterman, 2006), physical, and psychological effects on the children exposed (Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl, & Moylan, 2008; Osofsky, 2004). Exposure to IPV in childhood increases the risk of violence in adulthood (Heyman & Slep, 2002). Furthermore, co-occurring child abuse is frequently reported among children exposed to IPV (Herrenkohl et al., 2008).

Intimate partner violence has often focused on the violence perpetrated on women by men, but studies suggest that IPV is perpetrated by both men and women against each other (Dutton, 2006; Straus, 2005). The terms bidirectional, mutual, reciprocal, and symmetrical violence have been used to describe male-to-female and female-to-male IPV (Whitaker, Haileyesus, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007). Whitaker et al. (2007) in their study of 1,871 heterosexual relationships noted that reciprocal or bidirectional violence occurred in 49.7% of the quarried couples. Interestingly, females engaged in violence perpetration more frequently than men (Whitaker et al., 2007). Although men are typically stronger, they are less likely to reciprocate violence if attacked by their female partner (Whitaker et al., 2007). This could be explained by the norm that “men shouldn’t hit women” if struck first, or it could also be that men are not willing to report hitting their partner, unlike their female partners who will report violence (Archer, 2002). Bidirectional violence is reciprocal, although the frequency and severity of the violence may neither be similar nor equal between partners (Whitaker et al., 2007).

To understand the consequences and the impact of IPV, we must first understand the factors that influence men and the factors that contribute to IPV. Men are likely to perpetrate violent acts against their female sexual partners for various reasons including maintaining power or control within the relationship (Devaney, 2014) and believing that aggression is an acceptable form of conflict resolution (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; O’Leary, 1988). These constructs are facilitated by societal norms regarding gender roles that when not adhered to can create frustration that leads to violence (Devaney, 2014). Coupled with the expectations and aggression to carry out acts of violence, men have learned these behaviors through the modeling of their fathers, peers, characters on television or in movies, playing or watching sports, and even in military service (Gondolf, 2014).

Aside from the legal and judicial ramifications for male perpetrators of IPV, men involved in IPV also experience mental health problems such as anxiety and depression (Hester et al., 2015). Among male perpetrators of IPV, risky sexual behavior has been reported due to multiple partners (El-Bassel et al., 2001; Raj et al., 2006), the lack of condom usage during sexual relations outside of the primary relationship, and during forced sexual encounters with the victim of IPV (Amaro, 1995; Raj et al., 2006). Risky sexual behaviors may also be promulgated by substance and/or alcohol abuse (Caetano, McGrath, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Field, 2005; Foran & O’Leary, 2008).

In 2014, it was estimated that Hispanics residing in the United States totaled approximately 54 million (The United States Census Bureau, 2014a), and are expected to surpass 128.8 million by the year 2060 (The United States Census Bureau, 2014b). Mexicans represented 64% of the entire Hispanic subpopulation in 2012 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015; Pew Research Center, 2013). Additionally, 11% of the entire U.S. population was comprised of Mexicans (Pew Research Center, 2013). According to Cummings et al. (2013), the rates of IPV are higher among Hispanic couples (14%) in comparison to non-Hispanic White couples (6%). Hispanics also have higher IPV repeat occurrence rates (59%) when compared to non-Hispanic Blacks (52%) and White couples (37%) (Caetano, Field, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2005).

Certain social and behavioral characteristics have been identified as IPV perpetration risk factors including: anger (Holtzworth-Monroe & Hutchison, 1993; Whiting, Parker, & Houghtaling, 2014), impulsiveness (Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 1999, 2000, 2002), inability to control emotions (Caetano, Ramisety-Mikler, Caetano-Vaeth, & Harris, 2007), aggression (Plutchik & van Praag, 1997), impulsiveness, insensitivity, and guiltlessness (Hare, 2003; Sullivan & Kosson, 2006). Alcohol abuse (Kantor, 1997; Neff, Holamon, & Schluter, 1995; Perilla, Bakemon, & Norris, 1994; West, Kantor, & Jasinski, 1998) and cocaine (Coker, Smith, McKeown, & King, 2000; Parrott, Drobes, Saladin, Coffey, & Dansky, 2003) were also correlated with IPV perpetration. However, factors unique to men of Mexican origin including: Machismo, acculturation, and acculturation/acculturative stress may exist among men of Mexican origin (MMO) and augment their risk for IPV perpetration (Mancera, Dorgo, & Provencio-Vasquez, 2015). Machismo, a term coined by anthropologists, and promulgated by journalists, and scholars has negative connotations and implies that Mexican/Latino men engage in negative behaviors such as violence, adultery, and drunkenness (Gutmann & Viveros, 2005). Acculturation is how the beliefs and customs of one culture are adopted by another culture through interaction and observation (Castro, 2007; Redfield, Linton, & Herskovits, 1936). And acculturative stress is the adverse effects of adopting a new culture and the impact on psychological well-being (Born, 1970; Caetano et al., 2007).

The determinants that increase IPV perpetration risk among the rapidly growing population of Hispanic men of Mexican descent needs to be better understood (Mancera et al., 2015) as the incidence of IPV perpetration among Hispanic couples has increased (14%) in comparison to non-Hispanic White couples (6%) (Cummings, Gonzalez-Guarda, & Sandoval, 2013). The Patient Protection Affordable Care Act (2010) was expanded to include interpersonal and domestic violence screenings and counseling. Further exploration is warranted among this rapidly increasing population in order to understand the factors that place Hispanic men at risk for IPV perpetration. The purpose of this study was to describe risk factors for IPV perpetration among MMO, and to describe the process by which MMO are able to overcome IPV perpetration risk factors. The research question that guided this study was: How do men of Mexican origin understand and explain intimate partner violence?

Methods

Design

This qualitative research study was approved by the University of Texas at El Paso Institutional Review Board [study number 858279-1] and utilized Grounded Theory (GT) techniques were utilized for this research design. Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) extracts theories from the grounded data. Grounded Theory is used by researchers when studying social processes, interactions, and/or actions. The theory develops from categorized themes that emerge from the data which will be discussed below.

Setting

El Paso, Texas, situated along the U.S.–Mexico border was the study’s location. El Paso has an estimated population of over 835,000 with Hispanics comprising 81% of the community (U.S. Census, 2015). The yearly per capita income of $18,379 supports a family of three (U.S. Census, 2015), and is below the federal guidelines for poverty of $25,112 (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2015). The homogenous sample of MMO was from a neighborhood where a similar study had been conducted among women of Mexican origin. This facilitated the establishment of trust and gave insight into the issues the residents experienced.

Sample

Theoretical sampling along with the assistance of a key informant was used to recruit participants who lived in a neighborhood in El Paso, TX. Theoretical sampling is used by qualitative researchers as part of Grounded theory methodology to guide the generation of theory based on each participant’s description of real life events (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Grounded theory (Glasser and Straus, 1967) merges data collection and analysis: Grounded theory involves the progressive identification and integration of categories of meaning from data. Grounded theory is both the process of category identification and integration (as method) and its product (as theory). Grounded theory as a method provides guidelines on how to identify categories, how to make links between categories and how to establish relationships between them. Product of the grounded theory process is the emergence of a theory; which provides an explanatory framework with which to understand the phenomenon under investigation (Willig, 2013, p. 70).

Grounded theory methodology constantly compares the data utilizing open, axial, and selective coding, and guides the data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The first step in the process is the language open coding, which includes line-by-line analysis of the transcribed data in order to “break down” emerging categories by constantly compare the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Axial coding is the next step that looks at the unfolding relationships/connections between the categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Finally, selective coding is the identification of the core concepts or themes which are derived from the identified higher level abstracted themes and emerging categories supported by the data (Holton, 2007). Grounded theory reminds the researcher to continually revisit the data as more data are collected to understand the deeper meaning for clarity. Grounded theory facilitates the theoretical construction of social processes from raw data (Glaser, 1978, 1992; Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria for this study was limited to men between the ages of 18 and 55 who self-identified as being of Mexican origin, and had the ability to communicate in either English or Spanish. Participants were recruited from a federally qualified housing community. Men who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded from participation.

The principal investigator (PI) who served as the first author connected to a key informant who was a well-respected and a well-connected community member. This key informant was instrumental in promoting the research within the community and assisting with recruitment. The key informant also recommended strategic placement of fliers in high traffic areas. The success of this research was largely based on the key informant’s ability to connect with and recruit community members.

Data collection

The research team consisted of two qualitative experts and one mixed-methods expert, who assisted with the research design, grand tour and probing questions, and data analysis; two PhD students who collected the data, one of the PhD students (first author) revised the probing questions, back translated the data, and analyzed the data; and one graduate student who assisted with the note taking during the focus groups. Focus groups were conducted bilingually (English and Spanish) because the participants spoke both languages. Six focus groups with a total of 56 men (i.e., 8 to 12 men per group), were conducted at a designated community center, within a community room that provided privacy.

Focus group design

The research team traveled to the designated community to facilitate study participation. Participants were reminded by the key informant a day prior to the focus groups. The key informant would send verbal reminders to the participants with the spouses and children about the upcoming focus groups. As the men entered the designated community room, they were greeted by the research team. Refreshments were served as an “ice breaker” to familiarize the men with each other and the research team. The room was set up with tables and chairs in a large round table structure to facilitate discussion. The overall structure of how the focus groups would be conducted was also discussed.

Prior to the focus group interview, participants were given a cover letter containing information explaining the study and a consent form in the preferred language (i.e., English or Spanish). The PI then went over the content of the consent form in detail with the participants to ensure that all participants understood the objectives. Time was allotted for participants to read and sign the document. The confidentiality of the research was emphasized and discussed. It should be noted that disclosure of the topic of IPV in the cover letter may have kept some of the participants from fully participating in the focus groups. Various reasons for not openly participating could include fear of being labeled a perpetrator or the embarrassment of speaking about IPV. Participants were also informed that notes would be taken and that the conversations would be audiotaped for accuracy in translation and transcription. The men were not deterred from participating when the topic of the focus groups or audio taping was explained, and consequently none of the participants left.

Next, the PI administered a demographic questionnaire in the language of preference (English or Spanish). This questionnaire collected information such as country of origin and years living in the United States; relationship and family, such as current relationship status, living arrangements, and number of children; faith and beliefs, religious affiliation, and service attendance; income, such as gross income, number of person supported by income; and health-care utilization, such as having a regular doctor, having health insurance, and how health care is paid. The research team believed that these categories would help to understand the lives of MMO.

The PI explained the focus of the study, participant consent, confidentiality, and how participants’ identities would be protected by using alphabetic letters in place of names. The alphabetic letters had to be changed to numerals for the data analysis since there were a total of 56 participants. Questions from the participants were addressed and the informed consent was signed. The importance of confidentiality and anonymity was reinforced to the participants.

The thematic areas included in the focus groups were violence in the neighborhood, violence in the family, alcohol and substance abuse, and risky sexual behavior. The PI began with several grand tour questions that were developed in consultation with several members of the research team to guide the discussion. Examples of the grand tour questions included: Is violence a problem in your community? What is the process involved in becoming a victim of violence? What is the process in becoming a perpetrator of violence? Initial grand tour questions were followed with subsequent probing questions to elicit details and included: What are some of the concerns women in your community have about their partner with regards to violence? What are the circumstances surrounding conflicts that lead to violence? The grand tour and probing questions facilitated the participant’s descriptions of IPV risk factors. The questions were modified after each focus group based on the constant comparison of the participant responses. Focus groups were audiotaped to capture the participants’ descriptions of IPV risk factors, while observation notes provided descriptions of the participants’ interactions. Interactions that were observed include, nonverbal acknowledgments; facial expressions, verbal sounds of agreement and disagreement, and so on.

The duration of each focus group process was approximately 2 hr and included the informed consent and group discussion. Attendance varied between 10 and 12 MMO participating. Focus groups were conducted by the PI and a doctoral student, who served as a research assistant, in English, Spanish or both. The PI and doctoral student alternated moderating and taking notes. Upon completion of the focus groups a $30.00 cash incentive was given to each participant to compensate for their time and participation in the study.

Data analysis

To facilitate the translation of data, a bilingual translation/transcriptionist consultant was hired to translate and transcribe audiotaped recordings verbatim. The first author verified and back translated the transcripts after listening to the original recordings and corrected discrepancies. The data analysis began with the research team taking copies of the transcripts, reading the data line by line (open coding), and looking at the emerging relationships between the categories (axial coding). The emerging categories derived from the axial coding were then written on large easel pads and taped to the walls. This was followed by cutting the individual comments (data points) from the transcripts and taping them under the appropriate emerging categories. This process continued until the research team could see that several of the categories could be collapsed (selective coding) into higher level abstracted categories and the data points could substantiate them. The higher level categories were then analyzed, compared and collapsed (Charmaz, 2014), and led to the overarching theme of “self-reflection.” The data abstraction and resulting categories/theme illustrated the social process which contributed to risk factors for IPV perpetration among MMO. The grounded theory methodology ultimately resulted in a midlevel theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), Change Through Inspired Self-Reflection. This explains the motivating determinants that inspire MMO to change and move away from IPV perpetration.

Maintaining rigor and trustworthiness

Rigor within qualitative research establishes trust or confidence in the results of the study (Thomas & Magilvy, 2011). Rigor was established by following the model of trustworthiness of qualitative research (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). There are four components to establish trust: (a) credibility, (b) transferability, (c) dependability, and (d) confirmability. Credibility was established by incorporating triangulation to reduce researcher bias, and maintain rigor (Creswell, 2013; Denzin, 2009). Triangulation is used to validate and understand the phenomenon through the convergence of combined methods and multiple data sources. In this study descriptive statistics were used to gain a deeper understanding of the MMO (Patton, 1999). Furthermore, analyst triangulation was utilized for accuracy in the analysis, to abstract themes, and to clarify data points that may have been missed (Creswell, 2013; Denzin, 2009). Transferability was established through thick description (Geertz, 1973) which provided the details regarding the data collection and any observations made by the research team. Dependability was maintained by having a peer qualitative researcher conduct an external audit of the data for accuracy of findings and interpretations (Billups, 2014). This ensured the findings were supported by the data. Lastly, confirmability of the data was facilitated by an audit trail, which detailed the methodological procedures which could be used by another researcher to attempt replicating the study (Billups, 2014). Peer debriefing was also used to maintain rigor by engaging a peer researcher with expertise in qualitative research, with no expertise in the topic of interest, to assess and support emerging hypotheses (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Data saturation was achieved after the fifth focus group; however, an additional group was added for data congruence. Saturation is subjectively determined by the investigator and is the point at which the data yield no new categories, information, or themes and reinforces earlier data points (Glasser & Strauss, 1967).

Results

The sample was composed of 56 adult Hispanic men of Mexican origin, between the ages 18 and 55 years, who participated in six focus groups (group interviews). Each focus group consisted of 8–12 men. Participants of the focus groups were primarily born in the United States (n = 40), followed by Mexico (n = 15), and elsewhere (n = 1), the participant did not disclose the country of origin. The mean years of education was reported as 12 years (SD = 2.8). More than half of the men were unemployed (52%), either married or in a relationship (59%), and (46%) of the men did not cohabitate with a spouse or partner for reasons including separation from spouse, or not being legally married. More than half of the men (54%) had a monthly household income of $1,999.00 or less, and supported four or more persons (48%). A majority of the men did not have health insurance (68%) or a regular health-care provider (71%). Table 1 contains more thorough details regarding the description of the sample.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 56).

| Participant characteristics | M(SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | |

| United States | 71% |

| Mexico | 27% |

| Other | 2% |

| Years living in the United States | 21(9.5) |

| Years of education | 12(2.8) |

| Currently unemployed | 52% |

| Total monthly income (all sources after taxes) | |

| Less than $1,999 | 54% |

| Four or more persons supported by monthly income | 48% |

| Relationship status | |

| Married or in a relationship | 59% |

| Don’t live with spouse or partner | 46% |

| Number of children | |

| No children | 48% |

| One child | 11% |

| Two children | 7% |

| Three children | 11% |

| Four or more children | 23% |

| No previous HIV/STI testing | 61% |

| No health insurance of any type | 68% |

| No regular doctor of health-care provider | 71% |

Note. SD = standard deviation.

Source: HHDRC VIDA II Men’s Focus Group Data Set.

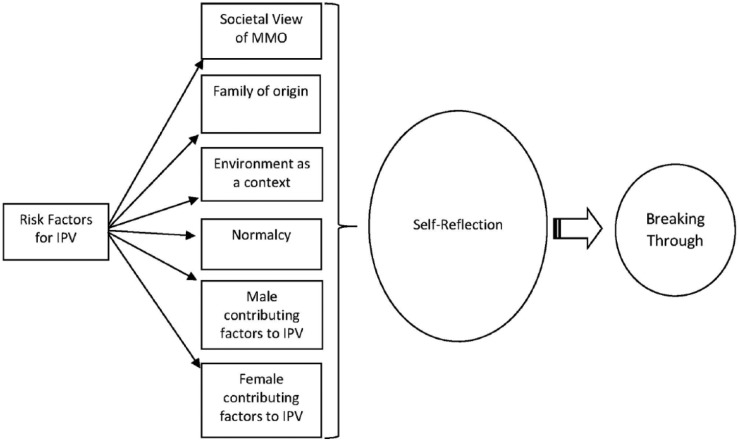

This section lays out the key findings from the MMO and risk factors for IPV perpetration, which led to the middle range theory, Change Through Inspired Self -Reflection. Risk factors for IPV were first discussed. Risk factors include Societal view of men of Mexican origin, Family of origin, Environment as a context, Normalcy, Male contributing factors to IPV, and Female contributing factors to IPV. Second, the self-reflected factors and how participants view themselves such as the Masked me and the Real me were described. Lastly, breaking through is described as the process of overcoming IPV perpetration through self-reflection. The entire social process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The social process of overcoming IPV. IPV = intimate partner violence.

Participant interviews included thick, rich descriptions of the social process that contributes to IPV perpetration risk factors among MMO. Grounded Theory categories and subcategories emerged from the data and are substantiated by selected participant quotes. The quotes provide clarity regarding the unique experiences of MMO within the context of IPV risk.

The social process that emerged from the data includes the overarching category, Self-reflection, with the higher level categories: the masked me, the real me, and the reflective me. The process describes how MMO move between the higher level categories because of self-perception as well as the perception of others. The emerging categories support the higher level categories and are substantiated with data points. The emerging categories are illustrated by: The societal view of men of Mexican origin, family of origin, environment as a context, normalcy, male contributing factors to IPV, female contributing factors to IPV, and breaking through.

Risk Factors for IPV

Intimate partner violence is complex and multifaceted. There are numerous risk factors for IPV such as low income, personality disorders, marriage dissatisfaction, having witnessed IPV as a child, or having been abused as a child, violence, and traditional, delineated, gender roles (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). These factors influence behavior and can increase the risk for IPV perpetration.

Societal view of men of Mexican origin

This category described how the MMO, in their own words, perceive the views and judgments of others. These views include the negative stereotypes of being a Mexican male, such as being machista, philanders, and heavy drinkers. The societal view of MMO facilitates the unwarranted negative expectations that MMO self-perceive that may result in IPV perpetration.

Participants expressed how they perceived machismo in the Mexican culture. There is a lot of stigma with the machismo culture…Many times you become violent when you drink. Even if when you are sober you are not violent after some drinks you might become more like a macho. You don’t see the consequences. You get blind when you drink and become an animal. Alcohol controls you. You are not thinking clearly. When you get home and your wife is mad at you because you are drunk and you punch her. Next day you see her with a black eye and you don’t know what happened because you were so drunk you don’t even remember it was you. I think to quit drinking is difficult. You have to pray because your family can’t help you, your mom can’t make you change.

The participants conveyed what it meant to be a macho, and its effect on subsequent behavior. Participant 29 expressed how he perceived machismo in the Mexican culture:

There is a lot of stigma with the machismo culture…Many times you become violent when you drink. Even if when you are sober you are not violent after some drinks you might become more like a macho. You don’t see the consequences. You get blind when you drink and become an animal. Alcohol controls you. You are not thinking clearly. When you get home and your wife is mad at you because you are drunk and you punch her. Next day you see her with a black eye and you don’t know what happened because you were so drunk you don’t even remember it was you. I think to quit drinking is difficult. You have to pray because your family can’t help you, your mom can’t make you change. (Participant 29)

These perceptions incorporated their views of Machismo in terms of gender, violence, and drinking and the expectations of what it means to be the man of the house. Participant 43 expanded on the theme of alcohol and drug use and described the shame associated with it, “It pisses me off. As Mexicans, we think we are going to be guilty anyways. That’s why they hit them bad, so it is at least worth it…it is sad to come from a background that just because you are Mexican they think you are a drunk.”

Participants connected themes of violence when comparing themselves to other groups. “Europeans are more open-minded. Being violent goes in the genes. Maybe things will change for the future generation” (Participant 15). Participant 40 described the delineated gender roles of Mexican culture that promulgated IPV:

I have noticed it with my family in Juarez. There women are inferior than men. Men come home from work and women are supposed to have the food hot and served for them. The house needs to be clean. The men get mad if things are not ready. My dad grew up like that, he thought women were worth less than men…Many men who hit their women use that as an excuse – my dad used to do it.

These examples described how MMO perceive their role and how others view them.

Family of origin

Family of origin is the term used to describe family factors that might contribute to IPV perpetration. Family factors are childhood family dynamics, relationships, and experiences that shaped and formed the MMO. Family factors are the family’s roots and family structure that established the attitude, beliefs, and behaviors of MMO. One participant described his family structure as a “blended family”:

I grew up with that [blended family], I had two little brothers and a sister. My two little brothers are from a different dad and growing up my dad treated them the same. He did his best, but it was always their grandparents telling them. He is not your dad he doesn’t have the right to tell you what to do. Don’t listen to him. That would cause tension between my parents… I think I was like five years old when my parents split up after a big fight that they had. I know that even many years later that keeps you from establishing a connection. (Participant 1)

This example of a blended family summarized many of the participant’s views regarding family upbringing.

Participants expressed their concerns regarding the lack of male role models. One participant while describing his personal experiences, tied the lack of role models to the cyclic violence of MMO:

My dad was at prison serving 18 years. He was abusive the way he was abused. It is a cycle. Most people are not strong enough to break the cycle. Too much pride to let things go. One day you just explode… I grew up in a violent home. My dad used to hit my mom every day. I have been married for almost 15 years and I have never hit my wife. I grew up with anger because he hit my mom. (Participant 51)

The lack of role models or perhaps the lack of positive role models has multiple implications for violence.

Environment as context

The environment as context describes where the men live and how this impacts views of self and others. The environment creates obstacles for the MMO and their families, such as a lack of community activities for families, difficulty securing and maintaining employment, and basic resources to help them cope with stressful living conditions. Participants described the community as violent, apathetic, steeped in alcohol and drug abuse, and little to no communication among neighbors. Such instances of violence are evident in Participant 9’s description:

When I first moved here I saw a couple fighting in the parking lot. A man pulled a lady out of her car. I would hear some yelling every now and then. I got a neighbor that is always yelling at their kids. She spanks them bad. That makes me sad because they are little kids. They are 4 or 5 years old. I can hear them from my house, but that’s not my business so I am not going to interfere with that, you know?

Another participant added,

It is our business but we don’t want to confront them because then we are going to have an enemy as a neighbor. There are people here that if you say something about them they vandalize your car or something. You can’t blame them because you didn’t see them.” (Participant 7)

Violence in the neighborhood was recurring themes among the participants.

Normalcy

Normalcy is how the participants perceived the violent neighborhood as normal and conventional. Normalcy describes how MMO became accustomed to hearing shouting and disputes, but perceived powerlessness to stop these behaviors. Normalcy is how MMO believe living conditions are “nothing out of the ordinary” and “a part of everyday life.”

The lack of money creates stress that contributes to IPV. When Participant 43 was asked, what contributed to IPV. The participant responded, “The income. Maybe they don’t have the income and they fight because of the lack of money.” Participant 9 added, “Financial problems cause violence too. Things are getting expensive. Sometimes you don’t know how the money is spent. I tried not to be at home because of the problems.” Financial struggles were an accepted part of life. Participants also discussed how the stress of living in this “normal” environment promoted IPV and even bad health. One participant noted, “Sometimes you have arguments with your spouse or kids not because you want to but because there is stress, but you have to find a way to release that stress” (Participant 54). Financial struggles and poor living conditions contributed to greater stress.

Male contributing factors to IPV

Male Contributing factors to IPV are the behaviors MMO display. These behaviors are driven by MMO’s beliefs regarding men, women, and relationship dynamics that contribute to IPV. Participants described behaviors that could contribute to IPV such as a lack of self-control, will power, and weakness. “No self-control. You are responsible for you. Many people don’t have the willpower. Everybody has the potential to do harm” (Participant 51). Participant 7 went on to express the idea that men don’t really understand women: “What I’ve found out about being married for 34 years is - don’t try to understand women. A preacher has told me that we shouldn’t try to understand women because women don’t understand themselves.”

Female contributing factors to IPV

Female Contributing factors to IPV are the behaviors that MMO believed women may contribute to IPV. Participants reported one behavior which was described as the crying wolf phenomenon. Crying wolf was explained as when a woman calls the police and reports IPV with fabricated stories, and in some instances self-inflicted wounds as evidence to get men arrested. Participant 20 described one such incident, “In my house I have seen women abusing men and they threaten them with the police. We as men can’t call the police; you need to know how to defend yourself.” Participant 25 added:

I would say “yes,” because women have now more power. The law is not the same for a man who beats another man that if a man beats a woman. I think the law should be impartial. I have seen it with my cousins. The police react differently if the victim is a man rather than a woman.

In some instances, the participants describe abuse perpetrated by women and how men can’t defend themselves because men must be respectful of women. Participant 33 explained:

I have heard about cases of women who hurt themselves to blame men. I think that makes men feel less of a man. There are women who hit men and that makes them think, I might be homosexual or something because I can’t touch her. Sometimes men are not the ones to blame and they go to jail anyways, but women take advantage of that. One day one of my coworkers went out with us to drink a beer. Next Monday he came to work with a black eye. We asked him and he said the cat attacked him. We knew his wife was abusing him and he didn’t have the courage to hit her back.

Participants described some of their interactions with their partners that involved violence and illustrated examples of IPV being bidirectional.

Participant 18 further described the difference regarding reporting IPV to the authorities in Mexico.

Here in the U.S. it is different. In Mexico nothing has changed. There you can hit women and nothing happens. Here women are more protected. There are many women who take advantage of that and accuse men without reason… Women have become violent. They know they have protection. I have a friend and his wife beats him, but he doesn’t want to go with the police because he is ashamed.

Participant 18 recognized that despite reports of the violence it was more than likely that there would be no consequences for these actions.

Self-Reflective Insights

Self-reflective insights refer to the masked me and the real me personas of the participants. MMOs report vacillating between these personas. These self-reflective insights are the external and internal factors that MMO believe contributed to IPV. The external factors contribute to the masked me category and are factors the MMO believe are not controlled. The internal factors contribute to the real me and are behavioral factors that contribute to IPV.

The masked me

The masked me described aspects of the participants that are not observable. This category includes attitudes and beliefs the MMO learned during childhood. The masked me includes the life experiences that shape adult identity. The masked me is derived from the IPV risk factors such as the societal view of MMO, the family of origin, and the environment as a context.

The real me

The real me described aspects of the participants that are observable. These are the factors that influence how the MMO see and perceive themselves on a daily basis. This category contains the attitudes and beliefs the MMO have that influence interpersonal relationships. This includes the contextual factors, normalcy, male contributions to IPV, and female contributions to IPV.

Self-reflection

Self-reflection is how the participants viewed themselves in the context of the lived environment, past experiences, interpersonal relationships, stereotypes, and the actualized person after overcoming IPV perpetration risk factors. One participant related, “At the end of the day what defines you is not where you come from but what you do” (Participant 53). Participant 41 described his life choices, “It is like a mirror and you can see if you want to be like that or not.”

Breaking Through

Breaking through describes an inner reflection that MMO experienced. This occurs when a man reports a positive change in attitudes and behaviors regarding intimate relationships with women. Breaking through is the realization that outcomes depend on the individual. Breaking through describes various examples of individuals connecting to or having some type of spiritual moment that initiated the change with some of the MMOs. Participant 2 commented, “I was involved in a case of domestic violence you don’t know what I lived with my wife. I needed to learn. We all need to learn to love ourselves and to respect to avoid problems.” Participant 51 describes how witnessing IPV changed his views, “I watched my dad hitting my mom. It helped me to want to be a better person.” While Participant 35 describes the impact IPV had on his life:

I think many people blame it on the parents or friends, but I think everything depends on us. If you want to be violent you will be, but it is on you. In my family everybody my dad and brothers used drugs and alcohol. Everybody thought I was going to be just like them, but look at me now. I am hardworking and I am nice to my children. Everything is on our minds.

Participant 29 added,

I was violent. I am from Ciudad Juarez. Violence leads to more violence. I almost got killed several times in Juarez because of violence and God helped me. I surrendered to God completely. I learned that what I was doing was wrong. I used to think that men from church were all gay. I was violent. I used to beat my kids really bad. I changed thanks to the word of the Lord… I only beat my wife twice…

Participant 9 talked about the impact his mother had on him, “Like me, I plan on being a good father. I don’t know my father; my mom has done everything by herself. She makes me want to be a better person. A better man. Love yourself first.” Participant 15 went on to challenge the assumptions of machismo, “…We need to change the cycle of the Mexican tequila, mariachi, Machismo.”

Breaking through is when MMO overcome IPV through self-awareness, reflection, and realization. Self-awareness allows the MMO to overcome all negative aspects of the family of origin, previous experiences, environment, and stereotypes. The MMOs have a breakthrough that enables a positive self-perception. The MMOs realize they can be better men for the love of their children and mothers. MMOs described the transitions they experienced upon self-reflection. Participant 29 related his past personality, “I used to be a violent man.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe risk factors for IPV perpetration among MMO. The resulting grounded theory developed from the data as the categories and themes emerged that also described the process by which MMO were able to overcome and surmount IPV perpetration risk factors. The research study was framed within the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) for violence prevention (Dahlberg & Krug, 2002) adapted from the Stokols (1996) model to better understand the complex behavioral influences that contribute to IPV. The SEM facilitates understanding how factors at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels affect the individual and their subsequent behavior. At the individual level factors include: age, educational attainment, and personal earnings, mental health disorders, observing IPV in childhood, substance or alcohol abuse, or temperament and demeanor (Mancera et al., 2015). Relationship factors include the interactions between intimate partners including communication skills, response to conflict, and the obedience to gender roles have been identified as risk factors for IPV perpetration (Mancera et al., 2015). Community factors are the settings where interactions occur such as home, work, and school. They have been reported as IPV risk factors, in particularly if the environment is plagued by poverty, disorder, or violence (Mancera et al., 2015). Societal factors are the customs, cultural and societal norms, economics, educational and social policies that promote discriminatory practices within society and have the penchant of increasing or decreasing violence (Mancera et al., 2015). The SEM facilitated understanding the contextual factors that MMO described as risk factors for IPV perpetration.

Various studies have focused on IPV victimization and Hispanic women (Castro, Peek-Asa, Garcia, & Krause, 2003; González-Guarda, Peragallo, Urrutia, Vasquez, & Mitrani, 2008; González-Guarda, Peragallo, Vasquez, Urrutia, & Mitrani, 2009) while relatively few have described the social processes that may contribute to IPV perpetration among MMO.

At the societal level, previous IPV studies substantiate many of this study’s findings, although several new categories emerged that require further investigation. The higher level category how others see me and its corresponding emerging category societal views of men of Mexican origin are the stereotypes others have about MMO. One prevalent stereotype within the Hispanic culture is Machismo that is frequently identified as a risk factor within relationships because of the acceptance of delineated gender roles (Mancera et al., 2015). Given that stereotypes such as Machismo are prevalent among other cultures when describing MMO, it is not surprising that MMO display the negative behaviors such as aggression, infidelity, and male dominance (Torres, Solberg, & Carlstrom, 2002) associated with Machismo.

At the community level, the proceeding higher level category the Real Me and ensuing emerging categories Environment as Context, Male Contributing factors to IPV, and Female Contributing factors to IPV have been reported in previous IPV studies. IPV perpetration risk increases in the context of poverty, violent communities, and urban areas (Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Harris, 2010; Caetano, Schafer, & Cunradi, 2001; Gonzalez-Guarda, Ortega, Vasquez, & DeSantis, 2010). IPV perpetration risk also increases with the mere perception of residing in a violent environment (Reed et al., 2009).

The relationship level, also consistent with the literature, was the feelings men had about the changing gender roles. Hispanic men may often feel stressed due to a sense of lost identity caused by changes in gender and social roles, beliefs, and routine daily life (Hovey, 2000; Salgado de Snyder, Cervantes, & Padilla, 1990). Changes in gender and societal roles that may cause stress for Hispanic men may also increase the risk for IPV.

At the individual level, the higher level theme, the masked me and its subsequent emerging category family of origin, are consistent with the literature as IPV risk factors. The masked me included childhood memories, family upbringing, observing the relationships between parents, and witnessing violence during childhood. Witnessing IPV in childhood increased IPV perpetration risk in adulthood (Perilla, 1999; Whitfield et al., 2003). Acts of IPV were also more plausible among men who were abused during childhood (Fagan, 2005; Fang & Corso, 2008; Gil-González, Vives-Cases, Ruiz, Carrasco-Portiño, & Álvarez-Dardet, 2008; McKinney, Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Nelson, 2009; White, McMullin, Swartout, Sechtrist, & Gollehon, 2008) due to the cyclical nature of generational violence (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010; Gonzalez-Guarda, Peragallo, Urrutia, Vasquez, & Mitrani, 2008; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2011).

Participants also described the frustration and the stress resulting from inadequate income to support families. This is consistent with the literature. Males were likely to perpetrate violence if the men earned less than female partners (Schumacher, Feldbau-Kohn, Slep, & Heyman, 2001; Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, & Tritt, 2004). The strain of unemployment or a lower paying job than the female was also correlated with IPV perpetration (Coker et al., 2000; Delsol & Margolin, 2004; Martin, Taft, & Resick, 2007; Stith et al., 2004). Among Hispanics and Blacks, lower income increased IPV perpetration risks (Cunradi et al., 2002; Perlman, Zierler, Gjelsvik, & Verhoek-Oftedahl, 2003; Sugihara & Warner, 2002). Mexican American men with lower incomes were reportedly at a higher risk for causing injury to the intimate partner (Perilla et al., 1994; Yllo & Strauss, 1990). Furthermore, low-income and feeling superior to partners increased the risk for injury (Sugihara & Warner, 2002). Relationship discord and stress are increased by the lack of resources and income which can lead to IPV perpetration (Caetano et al., 2001). Consequently, higher incomes allow people to live in safer and healthier neighborhoods which are at less risk for IPV (Telfair & Shelton, 2012).

Several study findings were distinct and have not been previously identified in the literature. The overarching category, self-reflection is a unique finding. It described the lenses through which participants viewed themselves contextually with regards to the environment, family of origin, relationships, stereotypes, and the self-awareness needed to become less violent.

Another unique finding was the emerging category of normalcy which has not been identified in the literature. One reason IPV may be considered “normal” is the fact that IPV perpetration rates are higher among Hispanics (Cummings et al., 2013). The higher IPV rates among this population coupled with cultural factors within the Hispanic community may contribute to the acceptance and normalization of violence. These two factors may explain why participants viewed IPV as a “normal” part of everyday life.

Lastly, breaking through describes a self-reflection. It is the deep, intrinsic, inner reflection participants experienced that caused them to break away from the negative persona. Breaking through is the transition from the masked me, and the real me, into the reflective me. This is the moment participants saw a positive self-transformation. This breakthrough leads to a change in attitudes concerning personal relationships with women, and corresponds to the change in behavior the participants had toward partners and children. Additionally, breaking through is the self-realization that outcomes depend on the individual. Breaking through was often the result of the love the MMO had for children, partners, mothers, and/or spirituality, which helped change these men from violent persons to loving, respectful fathers and husbands. Breaking through is the focal point of the midlevel theory that emerged from the data, Change Through Inspired Self-Reflection. This midlevel theory is not new or unique as it draws from the Theory of Transformative Learning (Cranton, 1994, 1996; Mezirow, 1991, 1995, 1996) which describes the process of how change is affected by the frames of reference by which our life experiences are understood. Change Through Inspired Self-Reflection explains the journey (social process) from IPV perpetration to becoming nonviolent men. This also helped explain why some of the MMO who had grown-up in violent environments did not continue the “cycle of violence.” Change Through Inspired Self-Reflection can facilitate understanding the intrinsic motivating factors that lead to positive behavior change.

Ultimately, the living conditions, perceptions of gender norms, the inability to provide for the family coupled with the lack of communication skills creates risk factors for IPV perpetration. Communication styles and skills were reported by Basile, Hall, and Walters (2013) as IPV perpetration risk factors due to the effect on satisfaction within a relationship. The interactions between intimate partners including communication skills, response to conflict, and the obedience to gender roles have been identified as risk factors for IPV perpetration (Mancera et al., 2015).

Study findings suggest that MMO have unique risk factors for IPV perpetration that can be mitigated. Because men traditionally do not speak openly about sensitive topics such as substance abuse, IPV and stress, male support groups may be an ideal way to mitigate negative outcomes. Support groups would enable men to discuss sensitive topics in a judgment-free environment and would facilitate supportive networks. This was supported by what occurred at the end of the focus groups. Participants shared contact information with each other and discussed the importance of mentoring younger men. This maybe an indicator that men (just like women) need to talk about experiences in order to purge negative thoughts and feelings, and recognize that men can learn from each other. MMO should be taught that Machismo has positive aspects such as courage, responsibility, and strength (Torres et al., 2002) that could be used to surmount IPV behaviors. These positive aspects of Machismo allowed the MMO to acknowledge weaknesses and begin communicating with each other, which could lead to much needed support and peer-mentoring to mitigate the negative aspects of Machismo.

Findings from this study have implications for clinical health-care practitioners and social workers who provide services to MMO. All clinicians must be educated to screen MMO for stress and its underlying causes such as unemployment, underemployment, and excessive alcohol use which may contribute to IPV perpetration. If, during the health encounter, any of these factors are identified, a referral to a mental health practitioner should be made.

Limitations

A few limitations must be acknowledged because of the potential effect on study findings. The sampling strategy was the first limitation because only MMO from a housing community were recruited because of experiences of violence within relationships and from within the community. This sampling was necessary to describe IPV risk factors among this population. The study population was also homogenous and may not reflect the experiences of other Hispanic subpopulations of men. Notwithstanding the study’s limitations, new information was obtained regarding unique risk factors for IPV perpetration among MMO. These findings can inform future studies among this population as it pertains to IPV perpetration risk factors.

Summary

The uniqueness of capturing the male perspective is of note because so few men openly discuss IPV within a group setting of other men. This study gave the MMO an opportunity to express their opinions and their personal experiences with IPV. None of the men justified reasons for perpetrating IPV. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a societal problem that affects many cultures. Among couples of Mexican origin, the increasing perpetration and perpetration recurrence rates necessitate a better understanding of risk factors that contribute to IPV. MMO may have unique risk factors they feel contribute to IPV. This study is important to men’s health because it explored the factors that can contribute to IPV but more importantly how these MMO overcame IPV. These unique factors must be considered when working with MMO who are at risk for IPV perpetration and for future interventions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Supported by Grant #5P20MD002287-06 REVISED and Grant 5G12MD007592 from the National Institutes on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center on Minority Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Amaro H. (1995). Love, sex, and power: Considering women’s realities in HIV prevention. American Psychologist, 50(6), 437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. (2002). Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 7(4), 313–351. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J., Graham-Kevan N. (2003). Do beliefs about aggression predict physical aggression to partners? Aggressive Behavior, 29(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Basile K. C., Hall J. E., Walters M. L. (2013). Expanding resource theory and feminist-informed theory to explain intimate partner violence perpetration by court-ordered men. Violence Against Women, 19(7), 848–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billups F. (2014). The quest for rigor in qualitative studies: Strategies for institutional researchers. The NERA Researcher, 52, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Born D. O. (1970). Psychological adaptation and development under acculturative stress: Toward a general model. Social Science & Medicine, 3(4), 529–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding M., Basile K. C., Smith S. G., Black M. C., Mahendra R. R. (2015). Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements (Version 2.0). Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., Field C. A., Ramisetty-Mikler S., McGrath C. (2005). The 5-year course of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(9), 1039–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., McGrath C., Ramisetty-Mikler S., Field C. A. (2005). Drinking, alcohol problems and the five-year recurrence and incidence of male to female and female to male partner violence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(1), 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., Ramisety-Mikler S., Caetano-Vaeth P. A., Harris T. R. (2007). Acculturation stress, drinking, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 1431–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., Ramisetty-Mikler S., Harris T. R. (2010). Neighborhood characteristics as predictors of male to female and female to male partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(11), 1986–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., Schafer J., Cunradi C. B. (2001). Alcohol-related intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Research and Health, 25(1), 58–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro F. G. (2007). Is acculturation really detrimental to health? American Journal of Public Health, 97(7), 1162. [Google Scholar]

- Castro R., Peek-Asa C., García L., Ruiz A., Kraus J. F. (2003). Risks for abuse against pregnant Hispanic women: Morelos, Mexico and Los Angeles County, California. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25(4), 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003). Injury prevention & control: Violence prevention, costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipvbook-a.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Minority health: Hispanic or Latino populations. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/populations/REMP/hispanic.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Violence prevention: Intimate partner violence: Risk and protective factors. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html

- Charmaz K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coker A. L., Smith P. H., McKeown R. E., King M. J. (2000). Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health, 90(4), 553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranton P. (1994). Understanding and promoting transformative learning: A guide for educators of adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cranton P. (1996). Professional development as transformative learning: New perspectives for teachers of adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings A. M., Gonzalez-Guardia R. M., Sandoval M. F. (2013). Intimate partner violence among Hispanics: A review of the literature. Journal of Family Violence, 28, 153–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi C. B., Caetano R., Clark C. L., Schafer J. (1999). Alcohol-related problems and intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the US. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 23(9), 1492–1501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi C. B., Caetano R., Clark C., Schafer J. (2000). Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: A multilevel analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 10(5), 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi C. B., Caetano R., Schafer J. (2002). Alcohol-related problems, drug use, and male intimate partner violence severity among US couples. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 26(4), 493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg L. L., Krug E. G. (2002). Violence–a global public health problem. In Krug E., Dahlberg L. L., Mercy J. A., Zwi A. B., Lozano R. (Eds.), World report on violence and health (pp. 1–56). Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Delsol C., Margolin G. (2004). The role of family-of-origin violence in men’s marital violence perpetration. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(1), 99–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N. K. (1973). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Devaney J. (2014). Male perpetrators of domestic violence: How should we hold them to account? The Political Quarterly, 85(4), 480–486. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton D. G. (2006). Domestic abuse assessment in child custody disputes: Beware the domestic violence research paradigm. Journal of Child Custody, 2(4), 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N., Fontdevila J., Gilbert L., Voisin D., Richman B. L., Pitchell P. (2001). HIV risks of men in methadone maintenance treatment programs who abuse their intimate partners: A forgotten issue. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(1–2), 29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan A. A. (2005). The relationship between adolescent physical abuse and criminal offending: Support for an enduring and generalized cycle of violence. Journal of Family Violence, 20(5), 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Corso P. S. (2008). Gender differences in the connections between violence experienced as a child and perpetration of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Journal of Family Violence, 23(5), 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Foran H. M., O’Leary K. D. (2008). Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1222–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-González D., Vives-Cases C., Ruiz M. T., Carrasco-Portiño M., Álvarez-Dardet C. (2008). Childhood experiences of violence in perpetrators as a risk factor of intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health, 30(1), 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. (1992). Emergence vs. forcing: Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G., Strauss A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf E. W. (2012). The future of batterer programs: Reassessing evidence-based practice. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda R. M., Ortega J., Vasquez E. P., De Santis J. (2010). La mancha negra: Substance abuse, violence, and sexual risks among Hispanic males. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 32(1), 128–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda R. M., Peragallo N., Urrutia M. T., Vasquez E. P., Mitrani V. B. (2008). HIV risks, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic women and their intimate partners. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 19(4), 252–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda R. M., Peragallo N., Vasquez E. P., Urrutia M. T., Mitrani V. B. (2009). Intimate partner violence, depression, and resource availability among a community sample of Hispanic women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(4), 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda R. M., Vasquez E. P., Urrutia M. T., Villarruel A. M., Peragallo N. (2011). Hispanic women’s experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and risk for HIV. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22(1), 46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann M. C., Viveros M. (2005). Handbook of studies on men and masculinities: Masculinities in Latin America (pp. 114–128). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hare R. D. (2003). The Hare psychopathy checklist revised (2nd ed.). Toronto: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl T. I., Sousa C., Tajima E. A., Herrenkohl R. C., Moylan C. A. (2008). Intersection of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 9(2), 84–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester M., Ferrari G., Jones S. K., Williamson E., Bacchus L. J., Peters T. J., Feder G. (2015). Occurrence and impact of negative behaviour, including domestic violence and abuse, in men attending UK primary care health clinics: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, 5(5), e007141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman R. E., Slep A. M. S. (2002). Do child abuse and interparental violence lead to adulthood family violence? Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 864–870. [Google Scholar]

- Holton J. A. (2007). The coding process and its challenges. In Bryant A., Charmaz K. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of grounded theory (pp. 265–289). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A., Hutchinson G. (1993). Attributing negative intent to wife behavior: The attributions of maritally violent versus nonviolent men. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(2), 206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey J. D. (2000). Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 6(2), 134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. P. (2008). A typology of domestic violence. A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and situational couple violence. Boston, MA: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor G. K. (1997). Alcohol and spouse abuse ethnic differences. In Galanter M. (Ed.), Recent developments in alcoholism (Vol. 13, pp. 57–79). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mancera B. M., Dorgo S., Provencio-Vasquez E. (2015). Risk factors for Hispanic male intimate partner violence perpetration. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(4), 969–983. doi:https://doi.org/1557988315579196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E. K., Taft C. T., Resick P. A. (2007). A review of marital rape. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12(3), 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Max W., Rice D. P., Finkelstein E., Bardwell R. A., Leadbetter S. (2004). The economic toll of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Violence and Victims, 19(3), 259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney C. M., Caetano R., Ramisetty-Mikler S., Nelson S. (2009). Childhood family violence and perpetration and victimization of intimate partner violence: Findings from a national population-based study of couples. Annals of Epidemiology, 19(1), 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J. (1995). Transformative theory of adult learning. In Welton M. (Ed.), In defense of the lifeworld. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J. (1996). Contemporary paradigms of learning. Adult Education Quarterly, 46(3), 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Neff J. A., Holamon B., Schluter T. D. (1995). Spousal violence among Anglos, Blacks, and Mexican Americans: The role of demographic variables, psychosocial predictors, and alcohol consumption. Journal of Family Violence, 10(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary K. D. (1988). Physical aggression between spouses: A social learning perspective. In Van Hasselt V. B., Morrison R., Bellack A., Hersen M. (Eds.), Handbook of family violence (pp. 31–55). New York, NY: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky J. D., Pruett K. D. (2004). Young children and trauma. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott D. J., Drobes D. J., Saladin M. E., Coffey S. F., Dansky B. S. (2003). Perpetration of partner violence: Effects of cocaine and alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 28(9), 1587–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5), 1193 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25158659 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perilla J. L. (1999). Domestic violence as a human rights issue: The case of immigrant Latinos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 21(2), 107–133. [Google Scholar]

- Perilla J. L., Bakeman R., Norris F. H. (1994). Culture and domestic violence: The ecology of abused Latinas. Violence and Victims, 9(4), 325–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2013). A demographic portrait of Mexican-Origin Hispanics in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/05/01/a-demographic-portrait-of-mexican-origin-hispanics-in-the-united-states/

- Plutchik R., Van Praag H. M. (1997). Suicide, impulsivity, and antisocial behavior. In Stoff D. M., Breiling J., Maser J. D. (Eds.), Handbook of antisocial behavior (pp. 101–108). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Raj A., Santana M. C., La Marche A., Amaro H., Cranston K., Silverman J. G. (2006). Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. American Journal of Public Health, 96(10), 1873–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield R., Linton R., Herskovits M. J. (1936). Memorandum for the study of acculturation. American Anthropologist, 38(1), 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Reed E., Silverman J. G., Welles S. L., Santana M. C., Missmer S. A., Raj A. (2009). Associations between perceptions and involvement in neighborhood violence and intimate partner violence perpetration among urban, African American men. Journal of Community Health, 34(4), 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara F. P., Anderson M. L., Fishman P., Bonomi A. E., Reid R. J., Carrell D., Thompson R. S. (2007). Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(2), 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado de, Snyder V. N. S., Cervantes R. C., Padilla A. M. (1990). Gender and ethnic differences in psychosocial stress and generalized distress among Hispanics. Sex Roles, 22(7–8), 441–453. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J. A., Feldbau-Kohn S., Slep A. M. S., Heyman R. E. (2001). Risk factors for male-to-female partner physical abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(2), 281–352. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg K. J., Baradaran L. P., Abbott C. B., Lamb M. E., Guterman E. (2006). Type of violence, age, and gender differences in the effects of family violence on children’s behavior problems: A mega-analysis. Developmental Review, 26(1), 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Stith S. M., Smith D. B., Penn C. E., Ward D. B., Tritt D. (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10, 65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. (1996). Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10(4), 282–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. L., Corbin J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A. (2005). Women’s violence toward men is a serious social problem. Current Controversies on Family Violence, 2, 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara Y., Warner J. A. (2002). Dominance and domestic abuse among Mexican Americans: Gender differences in the etiology of violence in intimate relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 17(4), 315–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan E. A., Kosson D. S. (2006). Ethnic and cultural variations in psychopathy. In Patrick C. J. (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Telfair J., Shelton T. L. (2012). Social determinants of health: The case of educational attainment. North Carolina Medical Journal, 75(5), 417–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E., Magilvy J. K. (2011). Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 16(2), 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J. B., Solberg V. S. H., Carlstrom A. H. (2002). The myth of sameness among Latino men and their machismo. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72(2), 163–181. Retrieved from 10.1037/0002-9432.72.2.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The United States Census Bureau. (2014. a). Facts for features: Hispanic heritage month 2014. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2014/cb14-ff22.html

- The United States Census Bureau. (2014. b). 2014 national popu-lation projections. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014.html?eml=gd&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2015). 2015 HHS poverty guidelines for affidavit of support. Retrieved from www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/form/i-864p.pdf

- West C. M., Kantor G. K., Jasinski J. L. (1998). Sociodemographic predictors and cultural barriers to help-seeking behavior by Latina and Anglo American battered women. Violence and Victims, 13(4), 361–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. W., McMullin D., Swartout K., Sechrist S., Gollehon A. (2008). Violence in intimate relationships: A conceptual and empirical examination of sexual and physical aggression. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(3), 338–351. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker D. J., Haileyesus T., Swahn M., Saltzman L. S. (2007). Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health, 97(5), 941–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield C. L., Anda R. F., Dube S. R., Felitti V. J. (2003). Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: Assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 166–185. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting J. B., Parker T. G., Houghtaling A. W. (2014). Explanations of a violent relationship: The male perpetrator’s perspective. Journal of Family Violence, 29(3), 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Willig C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Global Education Holdings. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2014). Violence and injury prevention: Prevention of intimate partner and sexual violence (domestic violence). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/sexual/en/

- Yllo K., Straus M. A. (1990). Patriarchy and violence against wives: The impact of structural and normative factors. In Struass M. A., Gelles R. J. (Eds.), Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families (pp. 383–399). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]