Abstract

The purpose of this integrative review was to explore the impact of prostate cancer (PCa) on the quality of life (QoL) and factors that contribute to the QoL for Black men with PCa. Prostate is recognized as the prevalent cancer among men in the United States. Compared to other men, Black men are diagnosed more frequently and with more advanced stages of PCa. Black men also experience disproportionately higher morbidity and mortality rates of PCa, among all racial and ethnic groups. The initial diagnosis of PCa is often associated with a barrage of concerns for one’s well-being including one’s QoL. As a result, men must contend with various psychosocial and physiological symptoms of PCa survivorship. Whittemore and Knafl’s integrative review method was utilized to examine empirical articles from the electronic databases of the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, PubMed, Project Muse, and Google Scholar. The time frame for the literature was January 2005 to December 2016. A synthesis of the literature yielded 18 studies that met the inclusion criteria for the integrative review. A conceptual framework that examined QoL among cancer survivors identified four domains that measured the QoL among Black PCa survivors: (a) physical; (b) psychological; (c) social; and (d) spiritual well-being. Social well-being was the dominant factor among the studies in the review, followed by physical, psychological, and spiritual. Results indicate the need for additional studies that examine the factors impacting the QoL among Black PCa survivors, using a theoretical framework so as to develop culturally appropriate interventions for Black PCa survivors.

Keywords: quality of life, general health and wellness, health-related quality of life, general health and wellness, prostate cancer, oncology/cancer, Black men

Prostate cancer (PCa) is recognized as the leading cause of cancer among men in the United States (“United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2014 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report,”). In 2017, the American Cancer Society (ACS) estimated 161,360 new cases of PCa in the United States. Data from the National Cancer Institute, Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (2017) reported that among all types of cancers in men and women, in the United States, PCa is the third most commonly occurring cancer (Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2016).

The pervasiveness of PCa also exists within the Black population. Empirical literature has established race, especially Black men, as a significant risk factor for PCa (Cooper & Linch, 2016; Lavery, Kirby, & Chowdhury, 2016; Sfanos & De Marzo, 2012). A comparison of incidence rates for PCa among Black men indicates 198.4 compared to non-White men at 114.8 per 100,000 (ACS, n.d.). Black men possess the highest incidence rates of PCa among all racial and ethnic groups. The high 5-year survival rate, 98.6%, for PCa in the United States is promising for those who are diagnosed with the disease (Howlader et al., 2017). However, in the United States, the mortality rate for Black men is twice as high as that for their White counterparts (Howlader et al., 2017).

PCa Survivorship

The term cancer survivor has been coined as “living with, through, and beyond a cancer diagnosis” (Bourke et al., 2015). The prevalence of PCa along with its high 5-year survival rates indicates a growing segment of the population who are living with PCa.

The disproportionately higher number of Black men diagnosed with PCa also suggests this population must contend with managing the symptoms associated with the disease (Finney et al., 2015). Symptoms often range from the physiological impact of surgery or radiation to the psychological impact of the cancer diagnosis itself (Finney et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2017). Physiological symptoms often include incontinence, erectile dysfunction, hot flashes, and decreased muscle and bone mass (Aning, 2016; Higano, 2003; Resnick et al., 2015). Additionally, the occurrence of depression and anxiety among men with PCa is an ever-present issue (Watts et al., 2014).

Research also indicates that Black men associate attitudes of fear and fatalism with a diagnosis of cancer (Hamilton et al., 2017). Previous studies indicated that Black men experienced decreased levels of physiological and psychological health when compared to the levels observed in White men (Chhatre, Wein, Malkowicz, & Jayadevappa, 2011; Lubeck, Grossfeld, & Carroll, 2001). An understanding of the adverse health issues experienced by Black men living with PCa is needed to in order to positively impact their health outcomes and improve their overall quality of life (QoL).

Quality of Life and Health-Related Quality of Life

QoL is purely subjective, and it rests solely on an individual’s perceptions of his or her life (Hamming & De Vries, 2007). It is the perceived satisfaction and goodness of life, which leads to the determination of one’s QoL (Diener & Suh, 1997). Based on a philosophical approach to defining the QoL, the concept consists of three major premises: (a) characteristics of a good life, (b) satisfying preferences for a good life, and (c) if one perceives one’s life as good or bad based on life experiences (Brock, 1993). Similarly, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is somewhat subjective and depends upon one’s perception of one’s level of physiological and psychological well-being based on one’s health or medical treatment (Bellardita et al., 2013). Literature indicates that the type of treatment largely determines the QoL and HRQoL of PCa survivors (Bellardita et al., 2013; Ferrell, Dow, Leigh, Ly, & Gulasekaram, 1995; Palmer, Tooze, Turner, Xu, & Avis, 2013). The physiological factors associated with QoL and HRQoL primarily pertain to urinary and bowel incontinence and erectile dysfunction, while the psychological factors include depression and anxiety (Campbell et al., 2007; Klotz, 2013; Rivers et al., 2012). Possessing a source of social support was a salient protective factor in increasing the QoL and HRQoL of Black men (Ferrell et al., 1995; Haque et al., 2009).

The high prevalence of PCa in the United States means many patients and families must contend with the psychological, physiological, spiritual, and social implications of PCa survivorship. Despite the majority of PCa diagnosed as localized (78%) or regionalized, (12%), a substantial proportion of the men engage in treatments with minimal benefits for their survival (Cancer Trends Report, 2018; Klotz, 2013). Literature indicates men often die from comorbidities other than PCa (Epstein, Edgren, Rider, Mucci, & Adami, 2012; Howlader et al., 2017). A study examined the aggressive treatment of indolent PCa among men of various races and socioeconomic backgrounds (Mahal et al., 2015). The results indicated 64.3% received aggressive treatment for indolent PCa (Mahal et al., 2015). The aggressive treatment of indolent PCa placed the men at risk for the avoidable harmful side effects of the treatment (Mahal et al., 2015).

A multifactorial process is therefore needed to understand the impact of PCa, especially on Black men. Previous literature indicated that various factors such as stigma and emotional well-being impact the outcome of men diagnosed with PCa (Jones, Steeves, & Williams, 2010; Penedo et al., 2013). The physical complications, such as bowel and bladder incontinence and sexual dysfunction associated with surgical and medicinal treatments, can also have a negative impact on the QoL of all those involved. It is especially important to assess the issues associated with PCa treatment, as the number of PCa survivors has increased over the past 25 years (DeSantis et al., 2014).

There are currently no studies that synthesize the available data regarding the QoL for Black men diagnosed with or treated for PCa. The current integrative review fills a gap in the literature regarding the synthesis of data on the QoL among Black PCa survivors by exploring factors associated with survivorship and QoL using a theoretical framework. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to (a) explore the impact of PCa on the QoL; and (b) identify factors that contribute to the QoL for Black men with PCa.

Methods

Theoretical Framework

Ferrell et al. (Ferrell et al., 1995) developed a conceptual framework to examine the QoL for cancer survivors. The framework is comprised of four specific domains to measure the cancer survivor’s QoL, including (a) physical; (b) psychological; (c) social; and (d) spiritual well-being (Ferrell et al., 1995). Each of the domains is comprised of various concepts, which are used to evaluate the cancer survivor’s QoL. For example, the physical well-being and symptoms domains is comprised of the following concepts: functional ability, strength/fatigue, sleep and rest, fertility, pain, appetite, and overall health (Ferrell et al., 1995). Based on the examination of the four domains in Ferrell’s conceptual framework, it was selected to serve as the theoretical framework for the current integrative review. The domains in Ferrell’s conceptual framework encompassed the themes of the articles in this integrative review. Therefore, the current integrative review used Ferrell’s conceptual framework as a guide for analyzing and reporting the findings from the articles.

Design

To explore the impact of PCa on QoL and to describe the factors contributing to QoL in Black men, an integrative literature review was conducted. This process entailed a step-by-step analysis and synthesis of published literature using rigorous guidelines outlined by Whittemore and Knafl (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). A comprehensive online database search of Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, PsycAPA, PubMed, Project Muse, and Google Scholar was conducted for related research articles published between January 2005 and December 2016. The search terms were used either alone or in combination: African American, Black, PCa, health-related quality of life, quality of life, and survivor. The search was limited to only peer-reviewed (scholarly) journals and articles were retrieved based on the stipulated timeline. The bibliographic references of the articles retrieved were also screened to identify additional references not captured during the initial search (the snowball method). An institutional review board approval for the study was not required due to the lack of confidential information or secondary data in the integrative review.

Inclusion Criteria

Criteria for articles included in the current study were articles written in English and articles focused specifically on Black males who were PCa survivors. Original, peer-reviewed articles were included if they utilized either qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method designs.

Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria used included articles not written in English, articles that included non-Black participants, studies conducted in non-peer-reviewed publications (e.g., conference proceedings, newspaper articles, dissertations, or book chapters), studies conducted in non-humans, or studies that did not have QoL or any QoL-relevant domain as one of its outcomes.

Data Abstraction

Data were extracted from each article using the following guideline: study purpose, setting, sample, and framework; design and methods; specific factors reported (instruments, if applicable); strengths and limitations; and key findings. Data from the article were also abstracted to include QoL domains outlined by Ferrell et al. (Ferrell et al., 1995). Finally, to ensure the accuracy of data synthesis, two researchers independently extracted the data and results were collated and synthesized.

Results

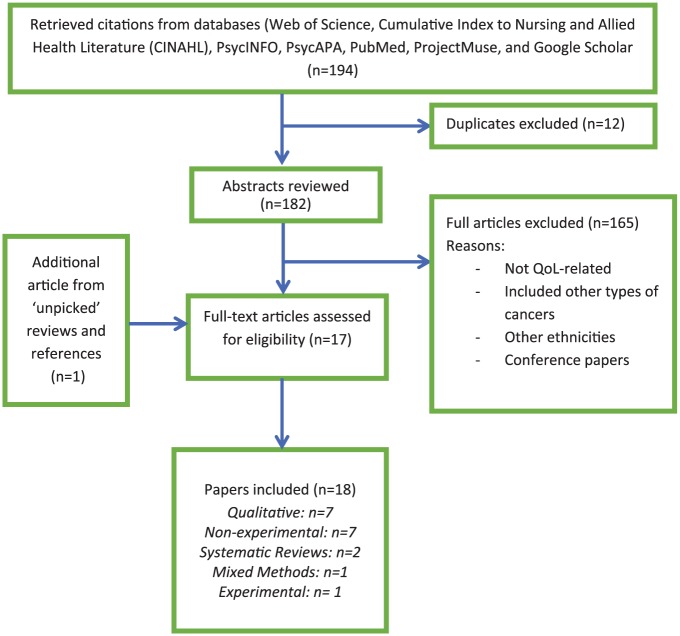

The search strategy yielded a total of 194 references, of which 12 were duplicates. All abstracts were reviewed for relevance. A total of 165 did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Eighteen articles were retrieved for further analysis, read, and reviewed. All articles were assessed for inclusion and exclusion criteria and re-rated for relevance. The final set contained 18 research studies. Figure 1 represents the flowchart for article selection.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and results flowchart from all sources.

Data were extracted on the country where the study was conducted, patient population, theoretical framework, design methods, specific factors, domains, strengths and limitations, and key findings. Table 1 has the summary of these findings.

Table 1.

Research on Factors Contributing to Quality of Life (QoL) in Black Men With Prostate Cancer (PCa).

| Citation and source/country | Purpose, setting, sample, and framework | Design and methods | Specific factors reported (instruments, if applicable) and domains represented | Strengths and limitations | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Campbell et al. (2007)

North Carolina, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To explore the feasibility and efficacy of coping skills training (CST) Setting: North Carolina, U.S.A. Sample: 40 couples Framework: CST |

Design: Randomized trial Methods: Survivors and spouses assigned to CST or usual care. Semistructured interviews and self-reported questionnaire; analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), thematic analysis of open-ended questions |

Factors/instrument(s): Self-efficacy, QoL (general and disease specific) Domains: Psychosocial, psychological |

Strengths: Use of telephone-based approach to assess coping in AA PCa survivors and their intimate partners Limitations: Small sample size, selection bias |

Partners who underwent CST reported less caregiver strain, depression, and fatigue, and more vigor, suggesting that telephone-based CST is a feasible approach that can successfully enhance coping in AA PCa survivors and their intimate partners |

|

Campbell et al. (2012)

North Carolina, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To examine how variation in masculinity beliefs are related to important indices of psychosocial functioning Setting: North Carolina, U.S.A. Sample: 59 AA Framework: Not stated |

Design: Quantitative exploratory Methods: Correlational analyses, hierarchical multiple regressions |

Factors/instrument(s): Expanded PCa Index Composite (EPIC), standard self-efficacy scale, depression and tension (i.e., anxiety) subscales of the Profile of Mood States-SF (POMS), Social/Family Well-being subscale of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General Domains: Psychosocial functioning (i.e., symptom distress, self-efficacy, negative mood, and functional and social well-being) |

Strengths: First study to examine masculine conformity variables as predictors of psychosocial functioning in AA PCa survivors Limitations: Cross-sectional, small sample size, low internal reliability of some subscales used |

Masculinity beliefs could be important therapeutic targets for improving the efficacy of cognitive behavioral interventions for men adjusting to PCa survivorship |

|

Chornokur, Dalton, Borysova, and Kumar (2011)

U.S.A. |

Purpose: Critically review the literature and summarize the most prominent PCa racial disparities Setting: N/A Sample: Not well defined Framework: Not stated |

Design: Systematic review Methods: Included studies that focused on disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in AA PCa survivors, results reported in comparison to other racial and ethnic groups |

Factors/instrument(s): N/A Domains: PCa disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival |

Strengths: In-depth look at the several types of disparities experienced by AA PCa survivors. Comparison of AA survivors to men from other racial/ethnic groups Limitations: Cross-sectional designs, lack of demographic reporting of means and standard deviations and of number of studies reviewed, no conceptual framework |

AA men persistently present with more advanced disease than Caucasian men, are administered different treatment regimens than Caucasian men, and have shorter progression-free survival following treatment. In addition, AA men report more treatment-related side effects that translate to the diminished QoL |

|

Dash et al. (2008)

New York, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To determine whether socioeconomic factors had a role in predicting the disease course of Black patients treated with radical prostatectomy Setting: New York Veterans Administration Medical Center and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Sample: 430 Black men Framework: Not stated |

Design: Cross-sectional using two cancer registries Methods: Bivariate analyses, recurrence-free survival analysis, using time-to-biochemical recurrence |

Factors/instrument(s): Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) recurrence Domains: Biologic factors |

Strengths: Large, focused sample of patient cohort using two centers Limitations: Selection bias as only Black men of lower socioeconomic status were included in the study |

Data suggest that socioeconomic factors have limited impact on PSA recurrence in Black men treated with radical prostatectomy. Thus, biologic factors might have a role in the poor outcomes in this population |

|

Emerson, Reece, Levine, Hull, and Husaini (2009)

Tennessee, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To determine whether an intervention program that includes peer education and a culturally competent education curriculum within a church-based setting will improve PCa knowledge, perception of risk, and screening rates among AA men Setting: 206 AA churches in greater Nashville area Sample: 345 Black men Framework: Health Belief Model |

Design: Quantitative, longitudinal with baseline, 3-month, and 6-month follow-ups using video messages and self-report questionnaires Methods: Difference of proportions tests, logistic multilevel regression |

Factors/instrument(s): Health Belief Model, Prostate Cancer Project (PCa risks, prevention, and the benefits of screening and making informed decisions) Domains: Self-efficacy, health belief, PCa knowledge |

Strengths: Large sample size and including relevant variables (such as knowledge) that have been reported to affect PCa screening participation in AA men Limitations: Selection bias as only Black men from churches were included. To generalize findings, male participants could be recruited from a variety of sites (i.e., workplaces, schools, barbershops, and other community organizations) |

This study demonstrated the need for education, community involvement, and increased access to encourage minority men to obtain needed health screenings. Also, that having insurance could likely lead to a significant decrease in health disparities |

|

Friedman, Corwin, Rose, and Dominick (2009)

U.S.A. |

Purpose: To explore AA men’s PCa information-seeking behaviors in depth, their capacity to use this information, and their recommendations for development of PCa prevention and screening messages and communication strategies for reaching other AA men with these messages Setting: Not stated Sample: 25 AA men Framework: Not stated |

Design: Mixed methods descriptive Methods: Qualitative, exploratory; semistructured interviews and focus groups. Descriptives of demographic data and thematic analyses of open-ended questions |

Factors/instrument(s): PCa information-seeking behaviors, capacity to use PCa information, recommended PCa messages, and suggested strategies for delivering PCa messages Domains: PCa decision-making |

Strengths: Qualitative description of communication strategies, mixed methods approach Limitations: Cross-sectional, no comparison group, no conceptual framework |

Barriers to information seeking were fear, poor resources, and limited family communication. Participants requested messages stressing men’s “ownership” of PCa delivered “word-of-mouth” by clergymen, AA women, and AA PCa survivors |

|

Gray, Fergus, and Fitch (2005)

Tennessee, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To reveal how PCa affects the lives of individual Black men and to show how a narrative approach can contribute to health psychology Setting: N/A Sample: Two Black men Framework: Not stated |

Design: Qualitative, exploratory; method: open-ended interview-based studyMethods: Each participant was interviewed four times |

Factors/instrument(s): The impact of PCa on Black men Domains: PCa experiences |

Strengths: Detailed narrative approach used to elicit the impact of PCa in Black men Limitations: Small sample size, no conceptual framework |

Black men, like all men with PCa, have diverse experiences and are influenced by a wide array of personal and societal factors. While the high risk of PCa among Black men makes proactive interventions advisable, such interventions will be most effective if the heterogeneity of men’s experiences are taken into account |

|

Hanson et al. (2013)

Maryland and Washington, D.C., U.S.A. |

Purpose: To test the hypothesis that despite ADT, ST would increase muscle power and mass, thereby improving body composition, physical function, fatigue levels, and QoL in an understudied subset of Black PCa patients on ADT Setting: Veteran Affairs Medical Centers in Washington, D.C., and Maryland Sample: 17 AA men Framework: Not stated |

Design: Quantitative, descriptive Methods: Within-group differences were determined using t-tests and regression models. Participants were examined on ADT at baseline and after 12 weeks of ST |

Factors/instrument(s): Muscle mass, power, strength, endurance, physical function, fatigue perception, and QoL Domains: Physical and physiological |

Strengths: Examined improvement in muscle function and functional performance in Black men Limitations: No comparison group, no randomization, small sample size, no conceptual framework |

ST significantly increased total body muscle mass (2.7%), thigh muscle volume (6.4%), power (17%), and strength (28%). There were significant increases in functional performance (20%), muscle endurance (110%), and QoL scores (7%) and decreases in fatigue perception (38%). Improved muscle function was associated with higher functional performance (R2 = 0.54) and lower fatigue perception (R2 = 0.37), and both were associated with improved QoL (R2 = 0.45), whereas fatigue perception tended to be associated with muscle endurance (R2 = 0.37) |

|

Jones, Taylor, et al. (2007)

Central Virginia, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To examine the cultural beliefs and attitudes of AA PCa survivors regarding the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities Setting: In-person interviews in participants’ homes and rural community facilities Sample: 17 AA men Framework: Not stated |

Design: Qualitative descriptives; personal interviews using a semistructured interview guide Methods: Inductive thematic analysis |

Factors/instrument(s): PCa, CAM, AA men’s health, culture, herbs, prayer, spirituality, and trust Domains: Spiritual |

Strengths: Explored spirituality and CAM use in AA PCa survivors Limitations: Small sample size, conceptual framework |

All participants used prayer often; two men used meditation and herbal preparations. All men reported holding certain beliefs about different categories of CAM. Several men were skeptical of CAM modalities other than prayer. Four themes were revealed: importance of spiritual needs as a CAM modality to health, the value of education in relation to CAM, importance of trust in selected health-care providers, and how men decide on what to believe about CAM modalities |

|

Maliski, Connor, Williams, and Litwin (2010)

California, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To describe the use of faith by low-income, uninsured AA/Black men in coping with PCa and its treatment and adverse effects Setting: Participants chose to interview in person at UCLA in a private room, in their home, or by telephone Sample: 18 AA male participants, between 53 and 81 years Framework: Grounded theory techniques to develop a descriptive model regarding spirituality and faith in the context of PCa treatment–related incontinence and/or erectile dysfunction |

Design: Qualitative Methods: Ethnicity-concordant, trained male interviewed using a semistructured interview guide for all interviews. Interviews lasted 1–2 hr. Men contacted for second interviews 3–6 months following the initial interview to clarify or expand on concepts identified in their baseline interviews or to confirm emerging themes |

Factors/instrument(s): Faith Domains: Spirituality, psychosocial, psychological |

Strengths: Use of in-depth qualitative interviews, in addition to follow-up interviews to expand on conversations from original interview. Use of grounded theory as a theoretical framework Limitations: Findings are specific to the situation of participants and cannot be generalized to all AA/Black men. Findings may not represent all religious beliefs. Faith is not as strict as the concept of religion, which is not confined to a particular religion or belief system. Older men were underrepresented |

Three themes identified: (a) perceptions of PCa; (b) coping through faith in God, and (c) provider, self, and family, reframing perceptions |

|

Jones et al. (2008)

U.S.A. |

Purpose: To examine the interactions and impact of family and friends of PCa survivors Setting: Data were collected in several clinic meeting rooms, participants’ homes, or a nonintimidating convenient setting for the participants Sample: 14 AA men between the ages of 51 and 83 years Framework: None identified |

Design: Qualitative Methods: The primary investigator, an AA male, sensitive and knowledgeable about the cultural background of the participants led the interviews. Semistructured interviews lasting 1 to 1.5 hr. Interviews were audiotaped, and actions were observed and recorded in field notes |

Factors/instrument(s): Two dominant themes emerged: (a) family involvement with PCa treatment decisions and (b) effect of PCa on relationships with women Domains: Psychosocial, psychological |

Strengths: Use of qualitative design to obtain a rich experience from AA PCa survivors. Focus of open communication and exploring the role of family and friend support for AA PCa survivors Limitations: Small sample size |

Participants indicated family involvement with cancer treatment as well as support from family and friends was critical during their treatment and experiences with PCa. The men did not feel their role as a male in their relationship was negatively impacted. The participants’ wives/partners indicated they would remain with them throughout their experience with PCa. There was a gap in communication between the participants and their wives/partners regarding the effects of the treatments on their relationship. Despite the men indicating that the quality of their erection was an important aspect in their lives, it did not take precedent over their health or their relationship |

|

Palmer et al. (2013)

North Carolina, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To examine AA PCa survivors’ involvement in treatment decision-making (TDM), and examine the association between TDM and QOL, using secondary data Setting: North Carolina, U.S.A. Sample: 181 AA PCa survivors, aged 40–75 years from the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry Framework: None identified |

Design: Quantitative, cross-sectional Methods: Secondary data analysis from a cross-sectional, case control study investigating genetic risks of PCa in AAs. Descriptive statistics, χ2, Fischer’s exact test ANOVA, Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD), and Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), conducted for analysis |

Factors/instrument(s): The participant’s sense of treatment decision-making, was measured by five questions, from a previous study involving white men and two additional questions from the modified Control Preference Scale. The EPIC measured QoL.Domains: Psychological; TDM and QoL |

Strengths: Believed to be the first study to examine TDM and posttreatment QoL for AA PCa patients Limitations: Due to cross-sectional secondary data analysis, causal inferences cannot be made. Possible selection bias. TDM factors were assessed using single-item measures. Self-report of PCa treatment. Sample consisted of highly educated AA PCa survivors from one state, which may not be representative of the population |

Majority of AAs preferred an active or collaborative role in medical decision-making, the roles influenced them, helped decide their choice of treatment, passive PCa patients reported better QoL compared to active patients. Higher QoL scores for bowel and hormonal domains and lower scores in the urinary and sexual domains |

|

Rivers et al. (2011)

U.S.A. |

Purpose: To identify and describe the most salient psychosocial concerns related to sexual functioning among AA PCa survivors and their spouses Setting: Not stated Sample: 12 AA PCa survivors and their spouses, age ranged between 51 and 70 years Framework: None identified |

Design: Qualitative Methods: Purposive sampling strategy. In-person interviews with AA PCa survivors and their spouses, concurrently, but seemingly separate. Interviews were audiotaped and professionally transcribed. Interview guide was pilot tested and 8 primary questions developed along with 15 potential probe questions |

Factors/instrument(s): QoL in relation to sexual functioning among AA men PCa survivors and their spouses Domains: Psychosocial issue of QoL in relation to sexual functioning among survivor AA couples of PCa |

Strengths: First qualitative study to examine and describe the psychosocial issues related to the sexual functioning of AA couples surviving PCa Limitations: No limitations identified by authors. Specific population indicates results cannot be generalized to population of AAs |

Key themes: (a) spousal support; (b) communication effects; (c) emotional effects; (d) physical effects; (e) sexuality-related effects; (f) erectile dysfunction; (g) incontinence. New information regarding sociocultural factors of seeking medical information, social support, communication strategies, management techniques, martial role delineation, and temporal orientation. Increased need for social support, which was reported by most couples. Difficulty in receiving social support due to lack effective communication and coping strategies. Lack of available information adversely affected couple’s communication. A strong marriage with good communication helped deflect the psychological distress of PCa |

|

Rivers et al. (2012)

Florida, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To explore the perceptions of AA PCa survivors and their spouses of psychosocial issues related to QoL Setting: In-person interview at a location of their selection Sample: 12 married AA PCa survivors aged between 40 and 70 years, recruited from a National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center registry and a state-based nonprofit organization to participate in individual interviews Framework: None identified |

Design: Qualitative Methods: Semistructured individual interviews of PCa survivor and spouse lasting 1.5 hr. Interviews audio-recorded and led by an AA interviewer and AA note taker. A total of 12 couples with the age of PCa survivors ranging from 51 to 70 and a mean of 59.75 years |

Factors/instrument(s): QoL was indicated by four domains, which were psychological, social, physical, and spiritual well-being Domains: Psychological and psychosocial |

Strengths: One of few studies to explore the psychological issues encountered by AA men and their spouses. An exploration of QoL beyond the physical dimensions; explores the role of spouses and psychosocial issues of AA men treated for PCa; and examines the role and influence of psychosocial issues experienced by AA men and their spouses Limitations: Few studies to compare the results of the study | Key themes: Under the four domains of QoL, the following themes emerged: (1) psychological well-being (a) fears; (2) social well-being (a) marital communication, (b) social support; (3) physical well-being (a) sexual functioning, (b) lifestyle; and (4) spiritual well-being. There was a lack of knowledge and limited information that was culturally appropriate regarding side effects of treatments; there was an absence of coping and problem-solving strategies that are culturally appropriate, a lack of communication strategies among the marital couples and health-care providers |

|

Moore et al. (2012)

North Carolina, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To determine if a particular set of health behaviors of health-care providers and AA and Jamaican men influence patient satisfaction from the AA’s perspective Setting: North Carolina, U.S.A. Sample: 505 AA and Jamaican men of African descent Framework: Modified form of Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services, which included two domains as opposed to four, which were: (a) health behaviors with two subdomains (process of medical care and use of personal health service) and (b) health outcomes evaluated by patient satisfaction |

Design: Descriptive, correlation design Methods: Secondary data analysis of cross-sectional data from the North Carolina-Louisiana Prostate Cancer Project (PCaP) |

Factors/instrument(s): Issues of health behaviors of health-care providers and AA and Jamaican men Domains: Psychosocial factors (patient-to-provider communication, interpersonal treatment, provider-to-patient communications, and habits of health-care utilization). |

Strengths: Increased literature on patient satisfaction as an outcome variable in association with treatment, decision-making, QoL, or survivorship outcomes based on experiences with health-care use Limitations: Causality could not be assumed due to the use of cross-sectional data. Generalization is not possible due to the specific characteristics of subjects in the data set. Most of the subjects in the study were highly educated, had higher levels of health literacy, and had increased use of the physician’s office. Patterns of communication were based on self-report, which was probably influenced by memory and recall. There was no consideration of interactions among the predicted variables |

Interpersonal treatment was one of the most important determinants for patient satisfaction. There must be a combination of adequate communication from health-care providers and good interpersonal treatment. There was an association between communication scores and increases in patient satisfaction. Provider-to-patient communication and patient satisfaction were associated. No association between health-care utilization and usual site for receiving health care and patient satisfaction |

|

Nelson, Balk, and Roth (2010)

U.S.A. |

Purpose: To clarify emotional well-being, distress, anxiety, and depression in AA men with PCa Setting: Two databases Sample: Total of 723 men (55 AA men were sampled) Framework: None stated |

Design: Secondary data analysis Methods: Descriptive statistics, independent measures t-test, and χ2 analysis |

Factors/instrument(s): Instruments consisted of QoL measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, Distress Thermometer, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Domains: Psychological, emotional well-being, distress, anxiety, and depression |

Strengths: Limited research on depression, anxiety, emotional well-being, and distress in AA men with PCa. Mix of early- and late-stage PCa patients and various treatments Limitations: Lack of nonspecificity for a type of AA PCa patient. Small sample size of AA men. No measures on resilience, no data on socioeconomic status. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale has not been validated in AA men with PCa |

After matching the sample, AA men seem to display a sense of resilience, demonstrating greater emotional well-being and a lower incidence of clinically significant depressive symptoms, compared with Caucasian men |

|

Sajid, Kotwal, and Dale (2012)

U.S.A. |

Purpose: A systematic literature review on interventions to improve (a) informed decision-making about PCa in screening eligible minority men and (b) QoL in minority PCa survivors Setting: U.S.A. Sample: Databases of MEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, and PsycINFO Framework: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) |

Design: Systematic review of the literature Methods: PRISMA; studies were evaluated for quality using the Downs and Black algorithm |

Factors/instrument(s): Studies grouped by educational program, printed material/booklets, telephone/videotape/DVD, and web-based Domains: Knowledge and self-efficacy for informed decision-making in screening eligible men, QoL and symptom management self-efficacy among PCa survivors |

Strengths: Systematic review of the literature to identify gaps in knowledge regarding decision-making to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in managing PCa Limitations: No assessment for risk of publication bias. Meta-analysis not performed. Lack of validity of several PCa knowledge scales, variation in the type of PCa knowledge, and knowledge levels in the study was assessed on the same day and no follow-up was performed |

Few articles regarding interventions to reduce disparities. Main strategy for PCa is informed decision-making, screening for PCa has fallen out of favor. Improved knowledge increased self-efficacy and appropriate interventions have increased QoL. Educational interventions were the most effective in improving knowledge among screening eligible minority men; cognitive behavioral strategies improved QoL for minority men with PCa |

|

Jones et al. (2011)

Maryland and Virginia, U.S.A. |

Purpose: To examine social support and economic barriers related to cancer care and assess whom the participants relied on for financial support and other resource issues during diagnosis and treatment Setting: Churches, barbershops, diners, and primary clinics in central Virginia and Maryland, U.S.A. Sample: 23 AA PCa survivors Framework: None stated |

Design: Qualitative. Methods: Five focus groups that were matched by gender and race Semistructured interview, conducted lasting 45–75 min, were tape-recorded and transcribed. Qualitative analysis program FolioViews™ and descriptive statistics. Thematic analysis method with a multistep analysis plan used |

Factors/instrument(s): Semistructured interviews to gather data regarding cancer support and financial issues Domains: Psychosocial |

Strengths: Qualitative design to explore cancer support among older AA men with PCa Limitations: Sample characteristics did not have much variance; most AA men were married, had health insurance, and lived with at least one other person |

There were two common themes: (a) Family and physician support are important, and (b) insurance is a necessity for appropriate health care. There were also differences in spirituality during diagnosis and treatment between rural and urban AA PCa survivors |

Note. AA = African American; ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; PCa = prostate cancer; QoL = quality of life; ST = strength training.

Summary of Study Design and Domains Measured

The majority (61%; n = 11) of the selected studies were published within the past 5 years. With the exception of one study (Gray et al., 2005) conducted in Canada, most of the studies were based in the United States. Most of the studies were either nonexperimental/cross-sectional (39%; n = 7; Campbell et al., 2012; Dash et al., 2008; Emerson et al., 2009; Hanson et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2010; Palmer et al., 2013) or used a qualitative design (39%; n = 7; Gray et al., 2005; Jones, Taylor, et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2008, 2011; Maliski et al., 2010; Rivers et al., 2011, 2012). In general, the sample size of the study was broad, ranging from 2 to 505 patients with varying age ranges. While most studies were conducted in Black men with PCa, only three studies (Campbell et al., 2007; Rivers et al., 2011, 2012) examined the impact of PCa treatment, coping, and its dynamics in Black PCa survivors and their spouses. The majority of the studies did not specify a study framework. For studies with frameworks listed, these ranged from coping skills training (Campbell et al., 2007) and the Health Belief Model (Emerson et al., 2009) to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for systematic reviews (Sajid et al., 2012). The QoL factors measured included psychosocial, psychological, biologic, emotional, physical, physiological, treatment decision-making, and sexual functioning factors.

Summary of Factors Associated With QoL in Black Men

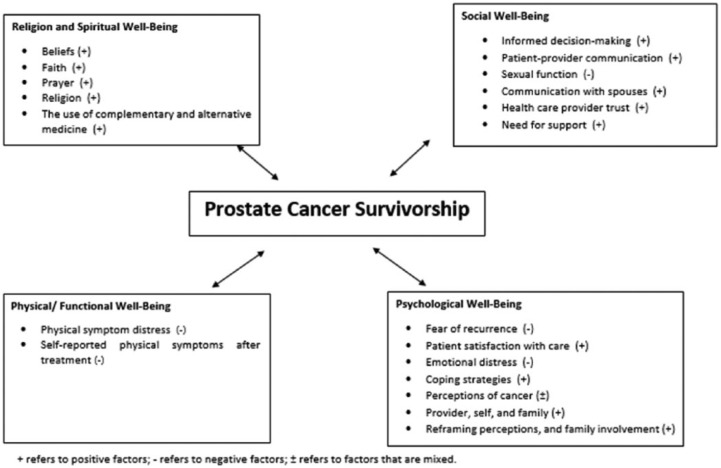

The factors extracted from the articles can be condensed to four main domains. These include spiritual well-being, physical/functional well-being, social well-being, and psychological well-being. Each of the domains contained various factors, which were associated with QoL in a positive or negative manner. A schematic model of the four domains in the review and their corresponding positive, negative, or mixed factors, which are associated with QoL among Black PCa survivors, is represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic model of integrative review results.

● Spiritual well-being domain: Factors within the spiritual domain were among the least represented in the included studies, with four studies (Jones, Taylor, et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2011; Maliski et al., 2010; Rivers et al., 2012) exploring such related variables. These spiritual outcome variables included beliefs, faith, prayer, religion, and the use of complementary and alternative medicine.

● Social well-being domain: This was the most represented domain in the selected articles. Ten of the selected studies utilized social factors affecting QoL (Campbell et al., 2012; Chornokur et al., 2011; Emerson et al., 2009; Friedman et al., 2009; Gray et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2008, 2011; Moore et al., 2012; Palmer et al., 2013; Rivers et al., 2012). Social factors were divided into the following subcategories: informed decision-making, patient–provider communication, communication with spouses, health-care provider trust, and need for support.

● Physical/functional well-being domain: About one third of the studies (n = 5) explored physical/functional issues affecting the QoL in African Americans with PCa (Campbell et al., 2012; Hanson et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2010; Rivers et al., 2011, 2012). Physical factors included physical symptom distress, self-reported physical symptoms after treatment, and sexual function.

● Psychological well-being domain: A total of seven studies explored psychological factors affecting QoL (Campbell et al., 2007; Dash et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2008; Maliski et al., 2010; Palmer et al., 2013; Rivers et al., 2012; Sajid et al., 2012), making it one of the most highly represented domains. The subcategories under this domain were fear of recurrence, patient satisfaction with care, emotional distress, coping strategies, perceptions of PCa, provider, self, and family, reframing perceptions, and family involvement with treatment decision.

Most of the selected articles focused on single QoL domains (Campbell et al., 2007; Chornokur et al., 2011; Dash et al., 2008; Emerson et al., 2009; Friedman et al., 2009; Gray et al., 2005; Hanson et al., 2013; Jones, Taylor, et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2010; Sajid et al., 2012) and five studies utilized two QoL domains (Campbell et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2008; Maliski et al., 2010; Palmer et al., 2013; Rivers et al., 2011). However, one study (Rivers et al., 2012) made use of all the four QoL domains as outcome measures.

Discussion

The purpose of the current integrative review is to explore the impact of PCa on the QoL of Black men and to identify factors that contribute to the QoL for Black men with PCa. Ferrell’s conceptual framework was ideal for the current integrative review based on its domains, which measure the QoL of cancer survivors. The 18 articles included in the current integrative review fit into at least one of Ferrell’s domains of (a) physical; (b) psychological; (c) social; and (d) spiritual well-being. By utilizing an 11-year time frame for the review, the most recent articles pertaining to QoL among Black PCa survivors were examined.

The findings of this integrative review suggest that the social domain, which encompasses the factors of informed decision-making, patient–provider communication, communication with spouses, health-care provider trust, and need for support, represents a positive association with QoL and Black PCa survivors. Likewise, all of the factors in the religion domain were positively associated with QoL. However, the physical/functional well-being domain was the only one in which all factors were negatively associated with QoL. Factors such as bladder and bowel incontinence along with erectile dysfunction were issues that influenced the QoL for PCa survivors. These results were not surprising, given that sexual functioning is often linked to one’s masculinity and the loss of it can cause significant distress without support from the spouse (Rivers et al., 2012).

The social well-being and psychological domain contained negative as well as positive factors that influenced QoL. Emotional distress was a factor within the psychological domain, which was negatively associated with QoL. Thus, PCa survivors who reported depression experienced decreased QoL (Campbell et al., 2007; Watts et al., 2014). The negative association of depression and PCa was also seen in a study that examined the impact of depression at diagnosis and an 8-year follow-up. Results of the study indicated an association between mortality and depression during treatment among men with PCa (Jayadevappa, Malkowicz, Chhatre, Johnson, & Gallo, 2011). Within the social well-being domain, sexual functioning had a negative association between QoL and Black PCa survivors. The issue of sexuality extends from the PCa survivor to the spouse or significant other and it is often a difficult issue to address (Blocker et al., 2006.; Chornokur et al., 2011). Again, the various domains and factors associated with QoL among Black men represent the complex physical and psychosocial approach to understanding the concept of QoL in Black PCa survivors.

Due to the prevalence of PCa among Black men, there must be a focus on the health outcomes of this population. Black men encounter fear and the physiological effects of PCa, which presents significant hurdles for achieving QoL. Hence, Black men often lack confidence in achieving QoL once they are diagnosed with PCa (Knight et al., 2004). The changes that occur from the treatment of PCa has an impact on PCa survivors as well as their families (Sanda et al., 2008). In addition, QoL is recognized as a pertinent issue, which may influence health policy to a greater extent than various health issues (Skarupski et al., 2007). The examination of QoL among Black PCa survivors can bring to light issues that are unique to this population. Those issues involve environmental surroundings, lower socioeconomic status, psychological stress from discrimination, and limited access to health resources that can also impact an individual’s QoL (Xanthos, Treadwell, & Holden, 2010). Any effort to address QoL among Black PCa survivors must include a multifactor approach, such as the one in this review.

Spiritual Well-Being

The domain of spiritual well-being was accounted for by more than one fourth (n = 5) of the studies. Religiosity was also a concept within Ferrell’s spiritual well-being domain that was present in the articles in the current review. The increasing inclusion of religion and spirituality in the examination of QoL supports the relevance of it as a domain within Ferrell’s model (WHOQOL SRPB Group, 2006). Religion and spirituality are often intertwined (Peterson & Webb, 2006), and for the purposes of this integrative review, the concepts were combined. Furthermore, religion and spirituality share a connection through seeking something sacred through experiences from the rituals or personal encounters (Yuen, 2007). In fact, religion was reported as a salient factor in the physical and emotional well-being of Black men with PCa (Hamilton et al., 2017; Maliski et al., 2010).

The prevalence of religion in today’s society is evident, given that 79% of Americans identified with some form of religion (“Gallup News. Most Americans still believe in God,” 2016). Similar to articles in this review, religion was found to be a strong predictor for preserving the health of African Americans (Roth, Usher, Clark, & Holt, 2016). The factors within the religion and spirituality domain consist of belief, prayer, and the use of complementary and alternative medicine. Findings from the review indicated that all of the factors were positively associated with QoL among Black PCa survivors. The results are similar to findings from previous studies, which indicated that faith and belief influence the health of African Americans (Blocker et al., 2006). The association between religion and spirituality and QoL among Black PCa survivors provides insight into the social and intrapersonal forces, which influence well-being in this population.

Social Well-Being

The invasive treatment regimens for PCa can often lead to various physical side effects. These side effects can range from achieving a partial erection to a complete loss of sexual functioning. The physical side effects of PCa and its treatment are often pertinent issues that impact the survivor’s QoL. Sexual function is a concept in the social well-being domain of Ferrell’s model as well as the articles in this review. The review indicated partial or complete loss of sexual functioning was a concern among the survivors of PCa (Gray et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2008; Rivers et al., 2011). An examination of the psychosocial health of adult cancer survivors revealed sexual functioning as the most frequently reported problem among PCa survivors (Baker, Denniston, Smith, & West, 2005). The negative association between sexual function and QoL among Black PCa survivors found in this review indicated the issues of masculinity and erectile dysfunction (Blocker et al., 2006). These issues are not unique to men undergoing treatments for PCa, and without the support of spouses or significant others, many of the men maybe at risk for a decreased QoL.

A cancer survivor’s roles and relationships and family distress were also concepts identified under the domain of social well-being. The wives of PCa survivors were a significant source of support and communication for their husbands (Gray et al., 2005; Rivers et al., 2011, 2012). An examination of the influence of marital status on cancer survival, which included PCa, suggested that social support was a benefit of marriage (Aizer et al., 2013). Results implied that the social support provided in a marriage decreased mortality and metastatic cancer rates among only the married men (Aizer et al., 2013). The family was viewed as a vital front in assisting the survivors to overcome the impact of the diagnosis and treatment (Jones et al., 2008). The spouse of a PCa survivor was an essential form of support for those who encountered difficulties with regaining sexual function (Rivers et al., 2012; Steginga et al., 2001). It is interesting to note that among the variety of articles in the current review, the concepts of appearance, employment, isolation, and finances, which are in the social well-being domain, were not present in the articles.

Physical Well-Being and Symptoms

The physical well-being domain was well represented throughout the current review. Among the concepts in Ferrell’s physical well-being domain were functional ability, pain, appetite, strength/fatigue, and overall health, which were largely present in the articles included in this review (Campbell et al., 2007; Chornokur et al., 2011; Hanson et al., 2013; Rivers et al., 2012). Bowel and bladder incontinence align with the concept of functional ability under the domain of physical well-being and symptoms. Furthermore, bowel and bladder incontinence were identified as symptoms in the articles that greatly impacted the QoL of PCa survivors (Campbell et al., 2007; Gray et al., 2005; Palmer et al., 2013). Unfortunately, a large portion of PCa survivors who undergo aggressive treatments (radical prostatectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy) experience issues of bowel and bladder incontinence (Alexson et al., 2013; Banerji et al., 2015; Ukoli, Barlow, Lynch, & Campbel, 2006; Potosky et al., 2000).

The concept of overall health is a factor within Ferrell’s physical/well-being domain, which had very little discussion in the articles. However, a study, which utilized Ferrell’s QoL conceptual model, identified the adoption of new health behaviors by African American men diagnosed with PCa (Rivers et al., 2012). The study reported a shift to eating healthier meals, decreasing caffeine in their diet, and increasing physical activity after PCa diagnosis. Ultimately, this adoption of a healthier lifestyle was beneficial for not only recovery after PCa but also their overall health (Rivers et al., 2012). An increase in their overall lifestyle has the potential to improve their QoL as PCa survivors.

Psychological Well-Being

Ferrell’s domain of psychological well-being contains concepts such as anxiety, depression, the overall perception of QoL, and control. The articles included in the current review addressed the overall concept of QoL among PCa survivors as part of the inclusion criteria for the review. Anxiety and depression were reported as factors that decreased the QoL in PCa survivors (Campbell et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2010). A diagnosis of PCa has the potential to evoke fear after considering the possibilities of bowel and bladder incontinence and loss of sexual functioning with various invasive or chemical treatments. Given that a large portion of cancer survivors report fear and anxiety and depression with their diagnosis (Baker et al., 2005; Hamilton et al., 2017; Jayadevappa et al., 2011; O’Malley et al., 2016), it was interesting that more articles did not include these factors for assessing QoL in Black PCa survivors. However, there were concepts within the psychological well-being domain, which were not addressed in the articles in this review, such as control, happiness, fear of recurrence and changes in cognition. The psychological well-being domain has the potential to provide a rich source of information regarding the challenges of facing PCa as a Black man. Future research warrants continued studies in the psychological domain for Black men to assist with developing culturally appropriate interventions focused on maintaining or improving QoL.

Implications for Improving QoL

There were two studies that examined the impact of stereotactic body radiation therapy and a comparison of stereotactic body radiation therapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy on the QoL of PCa survivors (Bhattasali et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2016). Stereotactic body radiation therapy is a promising treatment for PCa, which consists of high doses of radiation focused on the prostate. Therefore, damage to the surrounding tissues is minimized (Bhattasali et al., 2014). Hypofractionated radiotherapy is the delivery of radiation in small amounts over a shorter period of time (Johnson et al., 2016). Findings indicated that QoL decreased in the urinary, bowel, and sexual functioning among PCa patients who received stereotactic body radiation therapy (Bhattasali et al., 2014). Similarly, a comparison study of stereotactic body radiation therapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy for PCa indicated both treatments caused increased difficulties with bowel and bladder functions associated with QoL (Johnson et al., 2016). However, stereotactic body radiation therapy patients had less urinary symptoms compared to those who received hypofractionated radiotherapy (Johnson et al., 2016).

The spiritual well-being domain contained factors, which suggested possible intervention modalities for improving the QoL in Black PCa survivors. Hopefulness, a concept in the spiritual well-being domain of Ferrell’s QoL model, was also present within the studies in this review ( Jones, Underwood, & Rivers, 2007; Jones et al., 2011; Krupski et al., 2005; Rivers et al., 2012). Rivers et al. (Rivers et al., 2012) indicated a spirituality as a source of providing a sense of hope in light of the PCa diagnosis. Similar findings were observed in a study, which focused on the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Black PCa survivors. A mixed methodology design indicated that prayer was a complementary and alternative modality that was frequently used by African American PCa survivors (Jones et al., 2007). Additionally, spirituality was identified through the concept of faith in God and the health-care provider to provide the appropriate treatment and care, which corresponds with feelings of hopefulness (Jones, Lurie, & Throckmorton, 2016; Jones, Taylor, et al., 2007; Jones, Underwood, et al., 2007).

Religion is often a renowned facet in the lives of many African Americans. Spirituality was a theme, which emerged as being associated with PCa and QoL among 12 Black couples (Rivers et al., 2012). Both of the studies, as well as the previous studies mentioned, emphasized the need for physicians and all health-care providers to be cognizant of the important role that spirituality and God has in the lives of Blacks. The prevalence of religion and spirituality in the lives of Black people offers the possibility of these factors being used as intervention methods to improve their QoL.

There is a lack of literature that focuses on care plans for PCa survivors or preparing them for posttreatment outcomes (O’Malley et al., 2016). The uncertainty regarding treatment outcomes is a likely source of distress, which also impacts the PCa survivor’s QoL. Previous studies have examined the impact of various treatments for PCa on the physical and psychosocial health of the survivor (Bhattasali et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2016; Norris et al., 2015). The studies reported mixed results for increases and decreases in QoL among PCa patients treated with radiation, surgical, and strength-training modalities. For example, there was an improvement in the physical and psychosocial outcomes of PCa survivors who performed 2 days of resistance training (Norris et al., 2015). In contrast, there was a decrease in the psychosocial functioning of PCa survivors who took part in resistance training 3 days a week (Norris et al., 2015). Results suggest resistance training could be a viable intervention for improving the QoL among PCa survivors with continued research.

Identifying various modalities for increasing strength and decreasing fatigue were issues of interest among the PCa survivor’s QoL after treatment. Hanson et al. (Hanson et al., 2013) were the first to report that strength training led to increases in total body mass and muscle hypertrophy for Black men treated with androgen deprivation therapy for PCa. These studies highlight innovative interventions, which can improve various factors for determining the QoL of a PCa survivor. The aging population and the commonality of PCa among Black men warrant further research into facilitators and barriers for maintaining and improving their QoL.

Strengths and Limitations of Review

This integrative review utilized the proven stepwise method by Whittemore and Knafl to identify articles that explored the QoL of Black men with PCa (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). All the articles included in this review were thoroughly reviewed and examined for relevance before inclusion. This study included articles that utilized qualitative and quantitative methodologies, which enhanced a fuller understanding of the important QoL domains. Limiting articles to those published in the English language and the use of certain keywords during the search strategy could have resulted in the omission of important literature. Given that the purpose of this study was to explore factors contributing to QoL, clinical issues related to PCa were not included.

Recommendations for Future Research

The results from this current study indicate a lack of standardized measures designed to assess QoL in PCa survivors, especially among Black men. Thus, this warrants developing culturally sensitive instruments, informed by empirical studies and the use of theoretical frameworks, to capture such burden among Black men. Compared to the general population, PCa survivors are at increased disease- and treatment-related risks, which can impact their QoL. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the QoL outcomes related to this special population is warranted, especially through longitudinal studies. studies can help capture trends over time, particularly as it relates to treatment response and coping with long-term side effects of treatments. Such studies can also be conducted in larger, diverse population to make within-group comparisons among PCa survivors.

Conclusion

This integrative review synthesized specific outcomes based on QoL studies of Black men with PCa. Findings from this current study suggest that several factors are related to QoL in Black men with PCa. While confirming the common QoL factors (such as physical, social, and psychological), the study findings outline that unique factors such as spirituality are important to Black men with PCa. This integrative review provides continued support for the need to further examine the psychological and psychosocial impact of PCa among Black men. Future research from a multifactor perspective with an emphasis on spirituality is needed to help inform culturally appropriate interventions for Black PCa survivors.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to indicate that the interchangeable use of African Americans and Black men within this integrative review is based on the usage of the terms within the articles in the review.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aizer A. A., Chen M., McCarthy E. P., Mendu M. L., Koo S., Wilhite T. J., … Nguyen P. L. (2013). Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 3869–3876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexson B. A., Garmo H., Holmberg L., Johannson E. J., Odami O. H., Steineck G., Johannson E., Rider R. J. (2013). Long-term distress after radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in prostate cancer: A longitudinal study from the Scandinavian prostate cancer group-4 randomized clinical trial. European Urology, 64, 920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society (ACS). (n.d.). Key statistics for prostate cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- Aning J. (2016). Practical survivorship in prostate cancer. British Journal of Nursing (Mark Allen Publishing), 25(18), S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F., Denniston M., Smith T., West M. M. (2005). Adult cancer survivors: How are they faring? American Cancer Society, 104(11), 2565–2576. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji J. S., Hurwitz L. M., Cullen J., Odem-Davis K., Wolff E. M., Levie K., . . . Porter C. R. (2015). A prospective study of health-related quality of life outcomes for low-risk prostate cancer patients managed by active surveillance or radiation therapy. The Journal of Urology, 193, e513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellardita L., Rancati T., Alvisi M. F., Villani D., Magnani T., Marenghi C., … Salvioni R. (2013). Predictors of health-related quality of life and adjustment to prostate cancer during active surveillance. European Urology, 64(1), 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattasali O., Chen L. N., Woo J., Park J.-W., Kim J. S., Moures R., … Kowalczyk K. (2014). Patient-reported outcomes following stereotactic body radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Radiation Oncology, 9(1), 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blocker D. E., Romocki L. S., Thomas K. B., Jones B. L., Jackson E. J., Reid L., Campbell M. K. (2006). Knowledge, beliefs and barriers associated with prostate cancer prevention and screening behaviors among African-American men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98, 1286–1295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke L., Boorjian S. A., Briganti A., Klotz L., Mucci L., Resnick M. J., … Penson D. F. (2015). Survivorship and improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer. European Urology, 68(3), 374–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock G. W. (1993). Ethical guidelines for the practice of family life education. Family Relations, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L. C., Keefe F. J., McKee D. C., Waters S. J., Moul J. W. (2012). Masculinity beliefs predict psychosocial functioning in African American prostate cancer survivors. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6(5), 400–408. doi: 10.1177/1557988312450185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L. C., Keefe F. J., Scipio C., McKee D. C., Edwards C. L., Herman S. H., … Donatucci C. (2007). Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners: A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer, 109(2), 414–424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhatre S., Wein A. J., Malkowicz S. B., Jayadevappa R. (2011). Racial differences in well-being and cancer concerns in prostate cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 5(2), 182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chornokur G., Dalton K., Borysova M. E., Kumar N. B. (2011). Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate, 71(9), 985–997. doi: 10.1002/pros.21314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S., Linch M. (2016). Prostate cancer. InnovAiT, 9(5), 275–283. doi: 10.1177/1755738016639070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dash A., Lee P., Zhou Q., Jean-Gilles J., Taneja S., Satagopan J., … Osman I. (2008). Impact of socioeconomic factors on prostate cancer outcomes in Black patients treated with surgery. Urology, 72(3), 641–646. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis C. E., Lin C. C., Mariotto A. B., Siegel R. L., Stein K. D., Kramer J. L., … Jemal A. (2014). Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 64(4), 252–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Suh E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 40(1), 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson J. S., Reece M. C., Levine R. S., Hull P. C., Husaini B. A. (2009). Predictors of new screening for African American men participating in a prostate cancer educational program. Journal of Cancer Education, 24(4), 341–345. doi: 10.1080/08858190902854749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M. M., Edgren G., Rider J. R., Mucci L. A., Adami H. O. (2012). Temporal trends in cause of death among Swedish and US men with prostate cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 104(17), 1335–1342. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B. R., Dow K. H., Leigh S., Ly J., Gulasekaram P. (1995). Quality of life in long-term cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 22, 915–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney J. M., Hamilton J. B., Hodges E. A., Pierre-Louis B. J., Crandell J. L., Muss H. B. (2015). African American cancer survivors: Do cultural factors influence symptom distress? Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 26(3), 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. B., Corwin S. J., Rose I. D., Dominick G. M. (2009). Prostate cancer communication strategies recommended by older African-American men in South Carolina: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Cancer Education, 24(3), 204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup News. Most Americans still believe in God. (2016). Retrieved from http://news.gallup.com/poll/193271/americans-believe-god.aspx

- Gray R. E., Fergus K. D., Fitch M. I. (2005). Two Black men with prostate cancer: A narrative approach. British Journal of Health Psychology, 10(1), 71–84. doi: 10.1348/135910704X14429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton J. B., Worthy V. C., Moore A. D., Best N. C., Stewart J. M., Song M.-K. (2017). Messages of hope: Helping family members to overcome fears and fatalistic attitudes toward cancer. Journal of Cancer Education, 32(1), 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamming J. F., De Vries J. (2007). Measuring quality of life. British Journal of Surgery, 94(8), 923–924. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson E. D., Sheaff A. K., Sood S., Ma L., Francis J. D., Goldberg A. P., Hurley B. F. (2013). Strength training induces muscle hypertrophy and functional gains in Black prostate cancer patients despite androgen deprivation therapy. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68(4), 490–498. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque R., Van Den Eeden S. K., Jacobsen S. J., Caan B., Avila C. C., Slezak J., … Quinn V. P. (2009). Correlates of prostate-specific antigen testing in a large multiethnic cohort. The American Journal of Managed Care, 15(11), 793–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higano C. S. (2003). Side effects of androgen deprivation therapy: Monitoring and minimizing toxicity. Urology, 61(2), 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N., Noone A. M., Krapcho M., Miller D., Bishop K., Kosary C. L., … Cronin K. A. (2017). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2014. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; Retrieved from https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/ [Google Scholar]

- Jayadevappa R., Malkowicz S. B., Chhatre S., Johnson J. C., Gallo J. J. (2011). The burden of depression in prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 12, 1099–1611. doi: 10.1002/pon.2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. B., Soulos P. R., Shafman T. D., Mantz C. A., Dosoretz A. P., Ross R., … Brower J. V. (2016). Patient-reported quality of life after stereotactic body radiation therapy versus moderate hypofractionation for clinically localized prostate cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 121(2), 294–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. M., Lurie P. G., Throckmorton D. C. (2016). Effect of US Drug enforcement administration’s rescheduling of hydrocodone combination analgesic products on opioid analgesic prescribing. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(3), 399–402. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. A., Steeves R., Williams I. (2010). Family and friend interactions among African-American men deciding whether or not to have a prostate cancer screening. Urology Nursing, 30(3), 189–193, 166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. A., Taylor A. G., Bourguignon C., Steeves R., Fraser G., Lippert M., … Kilbridge K. L. (2007). Complementary and alternative medicine modality use and beliefs among African American prostate cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34(2), 359–364. doi: 10.1188/07.onf.359-364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. A., Taylor A. G., Bourguignon C., Steeves R., Fraser G., Lippert M., … Kilbridge K. L. (2008). Family interactions among African American prostate cancer survivors. Family & Community Health, 31(3), 213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. A., Underwood S. M., Rivers B. M. (2007). Reducing prostate cancer morbidity and mortality in African American men: Issues and challenges. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11(6), 865–872. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.865-872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. A., Wenzel J., Hinton I., Cary M., Jones N. R., Krumm S., Ford J. G. (2011). Exploring cancer support needs for older African-American men with prostate cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 19(9), 1411–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0967-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz L. (2013). Active surveillance for prostate cancer: Overview and update. Current Treatment Options in Oncology, 14(1), 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight S. K., Siston A. K., Chmiel J. S., Slimack N., Elstein A. S., Chapman G. B., . . . Bennett C. L. (2004). Ethnic variation in localized prostate cancer: A pilot study of preferences, optimism, and quality of life among black and white veterans. Clinical Prostate Cancer, 3(1), 31–37. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2004.n.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupski T. L., Fink A., Kwan L., Maliski S., Connor S. E., Clerkin B., Litwin M. S. (2005). Health-related quality-of-life in low-income, uninsured men with prostate cancer. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 16(2), 375–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery A., Kirby R. S., Chowdhury S. (2016). Prostate cancer. Medicine, 44(1), 47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2015.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lubeck D. P., Grossfeld G. D., Carroll P. R. (2001). The effect of androgen deprivation therapy on health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology, 58(2), 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahal B. A., Cooperberg M. R., Aizer A. A., Ziehr D. R., Hyatt A. S., Choueiri T. K., . . . Nguyen P. L. (2015). Who bears the greatest burden of aggressive treatment of indolent prostate cancer? The American Journal of Medicine, 128(6), 609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliski S. L., Connor S. E., Williams L., Litwin M. S. (2010). Faith among low-income, African American/Black men treated for prostate cancer. Cancer Nursing, 33(6), 470–478. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181e1f7ff [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. D., Hamilton J. B., Knafl G. J., Godley P., Carpenter W. R., Bensen J. T., … Mishel M. (2012). Patient satisfaction influenced by interpersonal treatment and communication for African American men: The North Carolina–Louisiana Prostate Cancer Project (PCaP). American Journal of Men’s Health, 6(5), 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. (2018). Cancer stats facts: Prostate cancer, survival statistics. Retrieved from https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html

- Nelson C. J., Balk E. M., Roth A. J. (2010). Distress, anxiety, depression, and emotional well-being in African-American men with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19(10), 1052–1060. doi: 10.1002/pon.1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris M. K., Bell G., North S., Courneya K. (2015). Effects of resistance training frequency on physical functioning and quality of life in prostate cancer survivors: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases, 18(3), 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley D. M., Hudson S. V., Ohman-Strickland P. A., Bator A., Lee H. S., Gundersen D. A., Miller S. M. (2016). Follow-up care education and information: Identifying cancer survivors in need of more guidance. Journal of Cancer Education, 31(1), 63–69. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer N. R. A., Tooze J. A., Turner A. R., Xu J. F., Avis N. E. (2013). African American prostate cancer survivors’ treatment decision-making and quality of life. Patient Education and Counseling, 90(1), 61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penedo F. J., Benedict C., Zhou E. S., Rasheed M., Traeger L., Kava B. R., … Antoni M. H. (2013). Association of stress management skills and perceived stress with physical and emotional well-being among advanced prostate cancer survivors following androgen deprivation treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 20(1), 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson M., Webb D. (2006). Religion and spirituality in quality of life studies. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1, 107–116. doi: 10.1007/s11482-006-9006-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Potosky A. L., Legler J., Albertsen P. C., Stanford J. L., Gilliland F. D., Hamilton A. S., . . . Harlan L. C. (2000). Health outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 92(19), 1582–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M. J., Lacchetti C., Bergman J., Hauke R. J., Hoffman K. E., Kungel T. M., … Penson D. F. (2015). Prostate cancer survivorship care guideline: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(9), 1078–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers B. M., August E. M., Gwede C. K., Hart A., Donovan K. A., Pow-Sang J. M., Quinn G. P. (2011). Psychosocial issues related to sexual functioning among African-American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses. Psycho-Oncology, 20(1), 106–110. doi: 10.1002/pon.1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers B. M., August E. M., Quinn G. P., Gwede C. K., Pow-Sang J. M., Green B. L., Jacobsen P. B. (2012). Understanding the psychosocial issues of African American couples surviving prostate cancer. Journal of Cancer Education, 27(3), 546–558. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0360-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth D. L., Usher T., Clark E. M., Holt C. L. (2016). Religious involvement and health over time: Predictive effects in a national sample of African Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 55(2), 417–424. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]