Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify effective channels, sources, and content approaches for communicating prostate cancer prevention information to Black men. The Web of Science, PubMed and GoogleScholar databases, as well as reviews of reference lists for selected publications, were searched to select articles relevant to cancer communication channels, sources or content for Black men, focused on male-prevalent cancers and published in English. Articles were excluded if they examined only patient–provider communication, dealt exclusively with prostate cancer patients or did not separate findings by race. The selection procedures identified 41 relevant articles, which were systematically and independently reviewed by two team members to extract data on preferred channels, sources, and content for prostate cancer information. This review revealed that Black men prefer interpersonal communication for prostate cancer information; however, video can be effective. Trusted sources included personal physicians, clergy, and other community leaders, family (especially spouses) and prostate cancer survivors. Men want comprehensive information about screening, symptoms, treatment, and outcomes. Messages should be culturally tailored, encouraging empowerment and “ownership” of disease. Black men are open to prostate cancer prevention information through mediated channels when contextualized within spiritual/cultural beliefs and delivered by trusted sources.

Keywords: prostate cancer, Black men, health communication, media channels, sources, cultural tailoring, cancer disparities, communication strategies, prevention

Black men are disproportionately affected by prostate cancer, with the highest rates of prostate cancer incidence and mortality of any racial/ethnic group in the United States (“Key statistics,” 2017). Black men are diagnosed at 1.7 times the rate of White men and are almost 2.5 times as likely to die of prostate cancer. A systematic review of the literature on these racial disparities concluded that prostate cancer tends to be more advanced at the time of diagnosis among Black men (Chornokur, Dalton, Borysova, & Kumar, 2011). The National Cancer Institute reports that prostate cancer is more likely to be diagnosed at earlier ages in Black men compared to Whites. For instance, Black men in their 40s are nearly three times as likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer as are their same-age White peers (“Cancer Health Disparities,” n.d.), and among men 65 and younger, Black men are nearly three times as likely to die of prostate cancer (He & Mullins, 2016).

Racial disparities in prostate cancer incidence and outcomes certainly stem in part from differential access to care and other social determinants, including lower socioeconomic status (Graham-Steed et al., 2013; Moses et al., 2017; Robbins, Whittemore, & Thom, 2000; Weiner, Matulewicz, Tosoian, Feinglass, & Schaeffer, 2017). Research suggests that higher prostate cancer mortality may reflect the fact that Black men seem to develop more aggressive types of prostate cancer compared to White men (Chornokur et al., 2011; Powell, Bock, Ruterbusch, & Sakr, 2010; Tsodikov et al., 2017). The disparity in cancer stage at diagnosis also could result from differences in screening participation rates, but research has produced conflicting findings about whether Black men are less likely than White men to be screened for prostate cancer (Jindal et al., 2017; McFall, 2007; Sammon et al., 2016; Swords, Wallen, & Pruthi, 2010).

The underrepresentation of Black men in prostate cancer research also interferes with the development of effective strategies for prevention and treatment of prostate cancer within this group (Ahaghotu, Tyler, & Sartor, 2016; Byrne, Tannenbaum, Glück, Hurley, & Antoni, 2014). Efforts to recruit Black men to participate in prostate cancer research, especially clinical trials, have been hindered by distrust and lack of knowledge about the benefits of cancer research, the informed consent process and how participant safety is assured (Byrne et al., 2014; Owens, Jackson, Thomas, Friedman, & Hébert, 2013). Reducing racial disparities in prostate cancer morbidity and mortality may depend in part on improving approaches to encouraging prostate cancer prevention and early detection as well as helping Black men (and their family members) understand the value of participation in clinical research. This will require identifying the most effective channels for reaching black men, the sources Black men consider most credible for providing prostate cancer information and the message content approaches Black men find most persuasive. Previous research has demonstrated that even passive exposure to prostate cancer information is significantly associated with prostate cancer screening (Kelly, Hornik, Romantan et al., 2010).

Another factor to consider is the role of prostate cancer knowledge in prostate cancer disparities. Prostate cancer knowledge has been reported to influence prostate cancer screening behaviors. For instance, Consedine et al. (2007) identified that U.S.-born European American men had significantly higher prostate cancer knowledge levels compared to U.S.-born Black men. In addition, the study reported that knowledge level had no impact on participation in digital rectal exam (DRE) screening, but knowledge interacted with fear in predicting prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening, which was less common among men with low knowledge levels and greater fear. A systematic review of 33 papers published before April 2010 and examining knowledge, awareness, and beliefs about prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening concluded that knowledge of prostate cancer risk, symptoms, diagnostic methods and treatment options contributes to greater willingness to be screened for prostate cancer (Pedersen, Armes, & Ream, 2012).

This systematic review concluded that, in general, prostate cancer knowledge was low across all racial groups, but was particularly low among Black men. A more recent study of 211 American-born and Caribbean-born Black men in South Florida demonstrated that U.S.-born men had higher knowledge scores, although in this study, knowledge was not a significant predictor of PSA testing within the past year (Cobran et al., 2013).

Facilitating Black men’s participation in clinical research and making informed decisions about their prostate health requires increasing their access to information about prostate cancer discoveries, especially those with implications for primary and secondary preventive interventions. It is important to employ effective and culturally appropriate strategies to communicate with Black men, taking into account their beliefs and attitudes about cancer, screening tests, communication with health-care providers and intergenerational sharing of health information (Blocker et al., 2006; Clarke-Tasker, 2002; Ford, Vernon, Havstad, Thomas, & Davis, 2006; Forrester-Anderson, 2005). Research has demonstrated that culturally tailored cancer communication does influence Black men’s prostate cancer knowledge and their likelihood of participating in prostate cancer screening (Jackson, Owens, Friedman, & Dubose-Morris, 2015; Wilkinson, List, Sinner, Dai, & Chodak, 2003). Researchers also have reported that even passive exposure to prostate cancer information is significantly associated with prostate cancer screening (Hornik et al., 2013; Kelly, Niederdeppe & Hornik, 2009).

The purpose of this article, therefore, is to examine the literature on best practices in communicating cancer information, especially about prostate cancer, to Black men. The goal is to identify the message approaches and communication channels most likely to be effective in improving knowledge of and attitudes toward prostate cancer screening and participation in research.

This manuscript reviews the published literature to answer three key questions about communicating prostate cancer information to Black men:

(1) What are the most effective channels for reaching Black men with prostate cancer information?

(2) Which sources (e.g., spokespersons) are most effective in communicating prostate cancer information to Black men?

(3) What message approaches are most effective in improving Black men’s knowledge about prostate cancer and their participation in prostate cancer screening and/or clinical trials?

Methods

These questions were addressed through a review of published studies that discussed best practices for communicating cancer information to Black men and/or provided insights into approaches to improving this communication. The review specifically focused on papers that provided direct recommendations about prostate cancer message content, sources, and channels. The aim of the study was not to critique these papers or to conduct a meta-analysis. Rather, the goal was to systematically review the current literature surrounding these topics in order to: (a) gain a deeper understanding of how to improve communication of prostate cancer information to Black men; and (b) assist in the development of evidence-based prostate cancer materials.

Data Sources

Systematic searches of the PubMed, Web of Science and Google Scholar databases were conducted using the following key words/phrases and boolean operators: “prostate cancer AND communication AND Black,” “Black men AND cancer communication,” “prostate cancer communication AND Black” and “prostate cancer communication in Black men.” PubMed was chosen over MEDLINE because the former is more comprehensive, meaning that articles included in MEDLINE also would be included in PubMed (“Fact SheetMEDLINE, PubMed, and PMC (PubMed Central),” n.d.). Web of Science and Google Scholar were searched as well to ensure that we identified relevant papers that might not have been indexed in the “medical” or “health” literature indexed by PubMed. Google Scholar was included because it returns results ordered according to relevance to the search terms, increasing the likelihood that highly relevant older studies would appear within the first 20 pages of results.1 Finally, searches of the grey literature were conducted using the databases OpenGrey, GreyLiteratureReport, and the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. However, these grey literature searches produced no articles that met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

publication after 19902

publication in English,

relevant to cancer communication and/or cancer education aimed at men without a prostate cancer history.

provides information about effective message channels, sources, and/or content, and

focuses on male-prevalent cancers (i.e., prostate, colon).

In regard to study design quality, the review took a broad approach, given that the study was not intended to evaluate effect sizes (Ogilvie, Egan, Hamilton, & Petticrew, 2005). Thus, the studies included ranged from randomized controlled trial designs to qualitative studies using focus groups or in-depth interviews.

Exclusion criteria

examined only patient–provider communication,

exclusively involved participants already diagnosed with prostate cancer, and

included Black men but did not separate findings by race.

Studies involving only prostate cancer patients were excluded because our study was focused on how best to promote prostate cancer prevention among Black men. Studies focused solely on patient–provider communication also were excluded because the study was the first step in developing a mediated intervention.

Data extraction

Two team members completed the systematic searches, and two additional team members—both experts on prostate cancer—independently validated the searches in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science, using the following procedures:

Identify papers in each of the databases using all four keyword search strings.

Independently screen all titles from the PubMed and Web of Science searches and the first 360 Google Scholar titles.

Meet to discuss differences and reach consensus on inclusion of papers based on titles.

Independently screen abstracts for all titles included after Step 3.

Meet to discuss differences and reach consensus on inclusion based on abstract reviews.

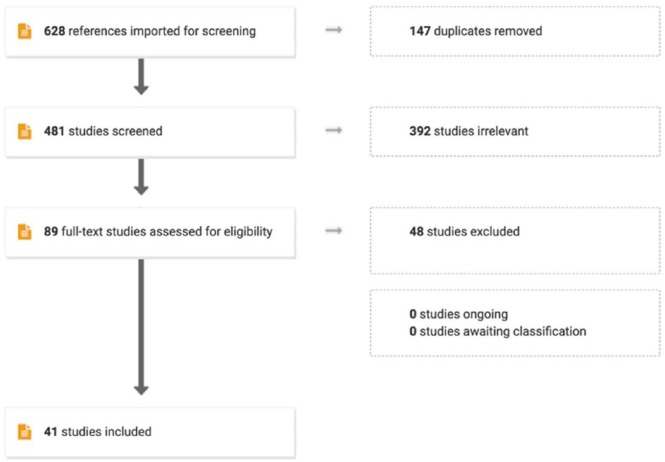

Using the keyword search strings in Google Scholar generated 39,700 papers. Two members of the research team screened the first 18 pages of results (360 titles). Google Scholar search results were reviewed until one entire page of search results included no relevant papers. Using the keyword search strings in PubMed and Web of Science generated an additional 268 references to be screened. These references were imported into Covidence, an online software designed for systematic review methodology. Articles previously screened for duplication, assessed for eligibility, excluded, and included for data extraction were reviewed once again using Covidence to electronically document the process and create an accurate PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA chart showing article selection process.

As the chart shows, 147 duplicates were identified and removed, leaving 481 studies to be screened for relevance. Review of the titles and abstracts of these articles identified 392 studies that were not relevant to our topic, leaving 89 full-text studies to be assessed for eligibility. Of these, 48 were found to examine only patient–provider communication, to include only men already diagnosed with prostate cancer or to fail to separate results by race, leaving 41 studies to be included in the review.

Data synthesis: Two team members used a systematic data collection strategy to independently review the 41 included papers, then met to discuss and reach consensus on findings. We used Qualtrics, an online survey software, to record information about each study, including the sample size, characteristics of the study participants, including age and race/ethnicity, the study methods, the year and location of the data collection, and what the study results revealed about the usefulness of various communication channels, credibility of sources and appropriateness of specific types of content.

Results

Seventeen papers included in analysis were purely quantitative (41%), 12 (29%) were purely qualitative, and 12 utilized a mixed-methods approach. The number of participants in quantitative studies ranged from 12 to 2,489, with the majority involving samples between 200 and 300. The largest qualitative study had more than 600 participants; however, the majority of qualitative studies included 20–40 participants. Thirty-six of the studies (88%) included only males, while five studies included Black females. For most studies, participants’ ages ranged from 35 to 70.

Effective Channels for Reaching Black Men with Prostate Cancer Information

One of the most common findings was that Black men prefer to receive prostate cancer information through interpersonal or word-of-mouth channels, particularly their physician, although community barbers, pastors, family members and friends also were frequently mentioned sources. Nine of the studies focused on or included significant mentions of a preference for word-of-mouth communication. For instance, Ross et al. (2011) reported that among Black men who had ever received prostate cancer information from any source, 86% (230) had obtained information from a doctor, and 36% (96) had received information from peers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Black Men’s Preferred Message Channels for Receiving CaP Information.

| Preferred message channel | Authors | Methods | N | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word of mouth/interpersonal | ● Friedman, Corwin, Rose, & Dominick (2009) | ● Focus groups and interviews | ● 25 Black men | ● Church pastors were perceived as credible and trustworthy source. |

| ● Fyffe, Hudson, Fagan, and Brown (2008) | ● Focus groups | ● 24 Black men | ● Participants described word-of-mouth as being a potentially successful strategy to distribute educational information about cancer. | |

| ● Releford et al. (2010) | ● Program review | ● 12 Black men, 16 White men | ● Barbers are generally trusted in community and act quite successfully as peer educators. | |

| ● Song et al. (2015) | ● Survey | ● 90 Black men | ● Participants preferred information from health professionals, followed by family and friends. | |

| ● Woods, Montgomery, and Herring (2004) | ● Focus groups/survey | ● 277 Black men | ● Older men are respected and trusted and can facilitate discussion among younger men. Personal physicians also are important sources. | |

| ● Kim et al. (2011) | ● Telephone interviews | ● 302 Black men & women, 312 Latino men & women | ● Interpersonal networks were important sources of information, but few in those networks were “telling stories” about prostate cancer. | |

| ● Weinrich et al. (1998b) | ● Survey | ● 497 Black men | ● Posting flyers and handing out information during services in Black churches is effective. | |

| ● Cowart et al. (2004) | ● Program review | ● 600 Black men (estimate) | ● Educating Black men in barbershops works because it is a setting where they are comfortable. | |

| ● Ross et al. (2011) | ● Survey | ● 268 Black men | ● 86% had obtained information from a doctor and 36% from peers | |

| TV | ● Griffith et al. (2007) | ● Focus groups | ● 66 Black men | ● TV second only to health providers as information channel. |

| ● Ross et al. (2011) | ● Survey | ● 268 Black men | ● 62% reported ever receiving CaP information from TV or radio | |

| Internet | ● Griffith et al. (2007) | ● Focus groups | ● 66 Black men | ● Men spent significant time seeking health information online. |

| ● Ross et al. (2011) | ● Survey | ● 268 Black men | ● 18% reported ever receiving CaP information from the Internet | |

| ● Sanders Thompson, Talley, Caito, and Kreuter (2009) | ● Focus groups | ● 43 Black men | ● The Internet was mentioned as a health information source, but health providers viewed as the only source one really needs. | |

| Print materials | ● Griffith et al. (2007) | ● Focus groups | ● 66 Black men | ● Written material is valued if it comes from a trusted source. |

| ● Ross et al. (2011) | ● Survey | ● 268 Black men | ● 61% reported ever receiving CaP information from printed materials | |

| ● Sanders Thompson et al. (2009) | ● Focus groups | ● 43 Black men | ● Print media (magazines, pamphlets & books) considered important sources of health information | |

| ● Taylor et al. (2001) | ● Focus groups | ● 44 Black men | ● Sources included newspapers & brochures. Men expressed preference for video & brief printed materials over telephone counseling. | |

| ● Bryan et al. (2008) | ● Focus groups | ● 12 Black men, 16 White men | ● Participants said it was important to provide individuals with printed materials. | |

| ● Kelly et al. (2010) | ● Survey | ● 2,489 men & women, all races | ● Men were more likely to find information in traditional media, especially local media, than online. | |

| ● Weinrich et al. (1998) | ● Survey | ● 1,264 Black men | ● Black news media were good channels for communicating about prostate cancer screening. | |

| Video | ● Taylor et al. (2006) | ● Experiment | ● 238 Black men | ● Both print & video significantly increased knowledge and reduced decisional conflict about CaP screening. |

| ● Taylor et al. (2001) | ● Focus groups | ● 44 Black men | ● TV was mentioned as a common source for health information. Men preferred video information to telephone counseling. | |

| ● Frencher et al. (2016) | ● Experiment | ● 120 Black men | ● Exposure to culturally tailored decision support video produced statistically significant increases in intentions to screen with PSA and decisional certainty about screening | |

| ● Odedina et al. (2014) | ● Pre- and post-test survey | ● 142 Black men | ● Exposure to culturally tailored video significantly increased CaP knowledge and intention to participate in CaP screening. Participants found video to be credible, informative, useful, relevant, understandable, not too time consuming, clear, and interesting. | |

| Text message | ● Song et al. (2015) | ● Survey | ● 90 Black men | ● Men preferred information from health professionals, followed by family and friends. However, most men had cell phones and found short text messages an acceptable way of receiving cancer information. |

Note. CaP = prostate cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Similarly, Friedman, Corwin, Rose, & Dominick (2009) reported that word-of-mouth was the most common prostate cancer information source, especially among low-literacy men. Song, Cramer and McRoy (2015) reported that low-income minority men, primarily Black men, relied on interpersonal health information sources but were less likely to consult family members and friends for prostate cancer information. Receiving prostate cancer information from medical professionals, but not family and friends, predicted prostate cancer screening participation. (Song et al., 2015). Prostate cancer information also can be successfully shared via interpersonal communication in familiar cultural settings such as barbershops, churches, and fraternal group meetings (Cowart, Brown, & Biro, 2004; Meade, Calvo, Rivera, & Baer, 2003; Releford, Frencher, & Yancey, 2010; Woods et al., 2004; Wray, Vijaykumar, Jupka, Zellin, & Shahid, 2011).

The Internet’s usefulness for prostate cancer communication varied across studies. Men in two focus group studies mentioned using the Internet for health information when they had specific questions (Griffith et al., 2007; Sanders Thompson et al., 2009), and 18% of the Black men in Ross et al.’s study (2011) reported previously obtaining prostate cancer information online. However, Song et al. (2015) identified the Internet as the least-often-used source for both general health and prostate cancer information.

Broadcast media have offered useful channels for disseminating prostate cancer information to Black men. In Ross et al.’s study of healthy Black men, 62% of those who had received prostate cancer information from any source reported receiving such information from broadcast media (Ross et al., 2011). In another study, TV was second only to medical providers as the most commonly mentioned source of prostate cancer information for Black men (Griffith et al., 2007). Other studies also noted the potential value of radio and television, especially specific radio and TV outlets that target Black audiences, as prostate cancer communication channels.

Participants in several studies responded positively to prostate cancer information videos, whether made available through television, online, or in-person (Frencher et al., 2016; Odedina et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2001, 2006). For instance, in a randomized trial of a booklet and video designed for Black men, Taylor et al. (2006) reported that exposure to the video improved prostate cancer knowledge, although this did not directly increase prostate cancer screening participation. Odedina et al. (2014) also documented the value of using video for prostate cancer education. Participants in this study noted that the video enabled portrayal of real-life situations and modeling of appropriate behavior, provided prostate cancer information in a lively and humorous way and overcame problems low-literacy men might have with written information. In addition, the brief video was shareable through social media, extending its reach beyond individuals who might see it in interpersonal settings (Odedina et al., 2014).

Most of the research suggests that print materials are not ideal for communicating prostate cancer information, especially among low-literacy populations (Friedman, Corwin, Dominick, & Rose, 2009). Some studies have suggested that text-based materials can be useful prostate cancer communication tools, especially if the information comes from a trusted source and/or is distributed in familiar settings such as churches or through Black news media (Griffith et al., 2007; Ross et al., 2011; Sanders Thompson et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2001). Song et al. (2015) argue that text-messaging and email may offer more cost-effective and accessible ways of reaching Black men with prostate cancer information. Their participants reported having greater access to cell phones than regular Internet access, and they preferred receiving information via email or text messages over viewing Web pages. In addition, prostate cancer information provided via text or email can be chunked into shorter, more easily understood segments, providing targeted information that requires little effort or skill to find and process (2006). A related study by the same research team demonstrated that low-income men responded favorably to receiving text messages about prostate cancer, using a system that enabled them to respond with questions about the information they had received and then receive answers via text. Among the 14 men who tried the text system, a majority said the system answered their questions well; nearly all expressed interest in using the system in the future to learn more about prostate cancer. In a later segment of the study, in which 10 participants used their own phones to receive messages and send questions, all 10 men agreed that the texts had made them better prepared to seek further information from doctors or other health professionals (McRoy, Cramer, & Song, 2014).

Effective Sources or Spokespersons for Communicating Prostate Cancer Information

The second objective of the study was to determine which spokespersons or sources would be most effective in communicating prostate cancer information to Black men, regardless of the channel used. Perhaps not surprisingly, most studies have indicated that Black men prefer learning about prostate cancer from familiar individuals such as family members (Ford et al., 2006; Fyffe et al., 2008; Meade et al., 2003; Song et al., 2015). A number of studies have pointed to the potential role of Black women, especially wives and girlfriends, as effective sources for communicating prostate cancer information, specifically the need for men to be screened for prostate cancer (Friedman, Corwin, Dominick et al., 2009; Meade et al., 2003; Wray et al., 2009). Black men also reacted positively to the idea of receiving prostate cancer from other familiar community members, such as the pastors of local churches (Blocker et al., 2006; Friedman, Corwin, Dominick et al., 2009; Powell, Gelfand, Parzuchowski, Heilbrun, & Franklin, 1995), barbers (Luque et al., 2011; Odedina et al., 2014; Releford et al., 2010), and radio personalities (Odedina et al., 2014) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Preferred CaP Message Sources Among Black Men.

| Preferred message sources | Authors | Methods | N | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | ● Meade et al. (2003) | ● Focus groups | ● 34 Black men, including 4 CaP survivors | ● Community members with whom participants could identify were key message sources |

| ● Song, Cramer, and McRoy (2015) | ● Survey | ● 90 Black men | ● Family members were important health information sources but were consulted about CaP less often than for other health issues. | |

| ● Fyffe et al. (2008) | ● Focus groups | ● 24 Black men | ● Family members viewed as good information sources. | |

| ● Ford et al. (2006) | ● Focus group | ● 21 Black men | ● Younger family members were mentioned as potential influence for screening information. | |

| Pastors/ministers of local churches | ● Blocker et al. (2006) | ● Focus groups | ● 29 15 Black men; 14 Black women | ● Participants suggested having local church pastors endorse educational materials, including allowing use of their photos |

| ● Powell et al. (1995) | ● Educational program | ● More than 1000 men had participated by June 1994 (90% Black) | ● Program delivered by black male physicians & cancer survivors had greater participation when pastor & other church staff were involved in the program. | |

| ● Friedman, Corwin, Rose, & Dominick (2009) | ● Focus groups and interviews | ● 25 Black men | ● Church pastors were perceived as credible and trustworthy source | |

| ● Odedina et al. (2014) | ● Intervention & Pre/Post survey | ● 142 Black men | ● Participants viewed pastors/ministers as credible sources, along with barbers & radio personalities. | |

| Barbers | ● Luque et al. (2011) | ● Interviews | ● 40 Black men | ● Barbers were viewed as effective, trusted community sources; barbershops seen as culturally familiar settings for cancer communication. |

| ● Odedina (2014) | ● Intervention & Pre/Post survey | ● 142 Black men | ● Barbers were viewed as credible sources. | |

| ● Releford (2010) | ● Program review | ● 12 Black men, 16 White men | ● Participants responded positively to models matched in age & ethnicity. | |

| CaP survivors | ● Wray et al. (2009) | ● Focus groups and discussions | ● 79 Black men | ● Interventions with survivor-led educational components could be successful. |

| ● Fyffe et al. (2008) | ● Focus groups | ● 24 Black men | ● Black male cancer survivors were viewed as helpful sources for information. | |

| ● Ford et al. (2006) | ● Focus groups | ● 21 Black men | ● Participants said survivor testimonials could influence screening decisions. | |

| ● Meade et al. (2003) | ● Focus groups | ● 34 Black men, including 4 CaP survivors | ● Participants preferred CaP survivors with whom they could identify, along with doctors & community members. | |

| ● Powell et al. (1995) | ● Educational program evaluation | ● More than 1,000 men had participated by June 1994 (90% Black) | ● Black CaP survivors successfully engaged participants on emotional aspects of cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment and recovery. | |

| Medical providers | ● Ross et al. (2011) | ● Survey | ● 268 Black men | ● Physician information was perceived as more reliable than information from peers. |

| ● Meade et al. (2003) | ● Focus groups | ● 34 Black men, including 4 CaP survivors | ● Physicians were preferred sources of CaP information. | |

| ● Jackson Owens, Friedman, and Hebert (2014) | ● Pre-test, educational intervention, Post-test | ● 28 Black men | ● Participants said including doctors in the education program was important. | |

| ● Sanders Thompson et al. (2009) | ● Focus groups | ● 43 Black men | ● Health providers were viewed as the most important source, even as the only source one would need. | |

| ● Griffith et al. (2007) | ● Focus groups | ● 66 Black men | ● Health providers were viewed as the most trusted source. | |

| ● Song et al. (2015) | ● Survey | ● 90 Black men | ● Participants preferred information from health providers. | |

| ● Steele et al. (2000) | ● Survey | ● 742 Black men | ● Black men advised by their doctors to have PSA test or DRE were 28.5 times as likely to report having been screened. | |

| Women | ● Friedman et al. (2012) | ● Focus groups & interviews | ● 43 Black men, 38 Black women | ● Women were perceived as credible and trustworthy sources. |

| ● Meade et. al. (2003) | ● Focus groups | ● 34 Black men, including 4 CaP survivors | ● Wives/females in men’s lives were mentioned as current and potential sources for health information. | |

| ● Wray et al. (2009) | ● Focus groups and discussions | ● 79 Black men | ● Women in men’s lives could be important sources for CaP information. | |

| Black community members in general | ● Pedersen et al. (2012) | ● Systematic review | ● Variable | ● Numerous studies mentioned the value of using respected members of the Black community and celebrities as prostate cancer information sources. |

Note. CaP = prostate cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; DRE = digital rectal exam.

Health-care providers were viewed as effective sources, even if the information was not being presented face-to-face (Griffith et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2014; Meade et al., 2003; Sanders Thompson et al., 2009). Prostate cancer survivors, especially from the local community, were perceived as credible sources (Ford et al., 2006; Fyffe et al., 2008; Meade et al., 2003; Wray et al., 2009). A few studies identified celebrities or well-known professional athletes as effective prostate cancer spokespersons for men who otherwise might not be interested in prostate cancer information (Allen, Mohllajee, Shelton, Drake, & Mars, 2009; Bryan et al., 2008; Pedersen et al., 2012).

Effective Message Content

The third objective for this review was to identify the most effective approaches to the content of prostate cancer communication to Black men. Not surprisingly, across all the studies examined, numerous topics were discussed as being important to include in prostate cancer communication (see Table 3). One overall theme, in fact, was that Black men should receive comprehensive information, including information about the causes and symptoms of prostate cancer (Friedman, Corwin, Dominick et al., 2009; Price, Colvin, & Smith, 1993), how screening is done (Jackson et al., 2014; Marks et al., 2004; Myers et al., 1999), and treatment options (Drake, Shelton, Gilligan, & Allen, 2010; Fraser et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2014; Myers et al., 1999). In one study, participants emphasized wanting to know about standard treatments available to “real” people, not only those available through clinical trials (Marks et al., 2004).

Table 3.

Black Men’s Content Preferences in CaP Messaging.

| Preferred message content | Authors | Methods | N | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emphasize early detection | ● Drake et al. (2010) | ● Intervention | ● 73 Black men | ● Decision tree visual was effective in helping men understand benefits & limitations of PSA. |

| ● Griffith et al. (2007) | ● Focus Group | ● 66 Black men | ● Benefits associated with early detection should be stressed, along with the need to screen absent symptoms. | |

| ● Odedina et al. (2008) | ● Mailed Survey | ● 191 Black men | ● Participants believed early detection could save their life. | |

| ● Wray et al. (2011) | ● Pre-test, intervention, post-test | ● 63 Black men | ● Messages should stress need for PSA and DRE screening & the value of early detection. | |

| ● Kripalani et al. (2007) | ● Experiment | ● 250 Black men | ● Simple message—“Ask your doctor about prostate cancer today”—was most effective in prompting conversations about prostate cancer. | |

| ● Miller et al. (2014) | ● Online experiment | ● 231 adult women with an African American male partner 35–69 years old | ● Brochures to show female partners how to overcome male resistance to screening were most effective among “high monitoring” partners of Black men. | |

| Causes and symptoms of CaP | ● Friedman et al. (2012) | ● Focus groups | ● 43 Black men | ● Information about CaP symptoms would motivate screening. |

| ● Price et al. (1993) | ● Experiment | ● 290 Black men | ● Educating men about symptom recognition should be combined with emphasis that screening is effective. | |

| ● Lepore et al. (2012) | ● Survey | ● 490 Black men | ● Inclusion of race-related risk information is important. | |

| CaP treatments | ● Myers et al. (1999) | ● Phone survey | ● 413 Black men | ● Educational information should include information about early detection, follow-ups for abnormal screening results and treatment options for those diagnosed with CaP. |

| ● Drake et al. (2010) | ● Educational intervention | ● 73 Black men | ● Intervention included discussion of how early detection could enable less aggressive forms of treatment. | |

| ● Marks et al. (2004) | ● Focus Groups | ● 24 Black men, 25 Black women | ● Participants wanted to know “everything the doctor knows,” including prostate anatomy, ethnic differences in risk, treatment options & outcomes/side effects of CaP treatment. Also wanted information about treatments available to “real people,” not just in clinical trials. | |

| ● Jackson et al. (2015) | ● Presentation | ● 60 Black men & women | ● Participants wanted information about risks & benefits of treatment vs. watchful waiting, details about CaP treatment. | |

| ● Fraser et al. (2009) | ● Questionnaire/Surveys and focus groups | ● 125 men Black men | ● Participants wanted information about side effects of treatment, including concerns about “loss of manhood” and sexual performance after surgery. | |

| Screening process | ● Marks et al. (2004) | ● Focus Group | ● 24 Black men, 25 Black women | ● Participants wanted explanation of why DRE is used for CaP screening |

| ● Myers et al. (1999) | ● Phone survey | ● 413 Black men | ● Men wanted information about procedures used for early detection. | |

| ● Jackson et al. (2015) | ● Presentation | ● 60 Black men & women | ● Screening information was important, including information about the exam process. | |

| ● Allen et al. (2007) | ● Focus groups and key informant interviews | ● 108 Black men | ● Men would not object to DRE if information provided detailed & thorough rationale for its use. | |

| Overall health context | ● Allen et al. (2007) | ● Focus groups and key informant interviews | ● 108 Black men | ● Participants wanted holistic health information, including information about physical activity, stress relief and sexual health. |

| ● Fraser et al. (2009) | ● Questionnaire/Surveys and focus groups | ● 125 Black men | ● Men wanted information connecting CaP with broader health issues. | |

| ● Holt et al. (2009) | ● Focus groups and cognitive response interviews used to test print material | ● 36 Black men | ● Man wanted information about the role of family history, race and diet in CaP. | |

| ● Wang et al. (2013) | ● Interviewer-administered survey | ● 95 Black men, 9 White men | ● Information must be very simple and provide extensive explanation to be understood by low-income, low-education men. | |

| Spiritual context | ● Blocker et al. (2006) | ● Focus groups and questionnaire | ● 14 Black men 15 Black women |

● Participants agreed church could play influential role; preferred endorsement of educational/promotional material by pastor of local church. |

| ● Holt et al. (2009) | ● Focus groups and cognitive response interviews used to test print material | ● 36 Black men | ● Participants wanted spiritually based information to appear early and clearly in CaP education booklet. | |

| Positive framing for survival if diagnosed | ● Bryan et al. (2008) | ● Focus groups | ● 12 Black men, 15 white men | ● Participants responded positively to empower text. |

| ● Marks et al. (2004) | ● Focus groups | ● 24 Black men & women | ● Participants wanted positive messages expressing hope for Black CaP patients | |

| ● Underwood (1992) | ● Survey | ● 236 Black men | ● Communications should emphasize survival benefits of early detection. | |

| Cultural tailoring | ● Frencher et al. (2016) | ● Experiment | ● 120 Black men | ● A culturally tailored decision support instrument was significantly better than a non-tailored instrument in increasing intentions to screen for CaP and increasing decisional certainty. |

| ● Odedina et al. (2014) | ● Pre- and post-test survey | ● 142 Black men | ● A culturally tailored video improved knowledge and intentions to screen for CaP. |

Note. CaP = prostate cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; DRE = digital rectal exam.

Six studies specifically noted the importance of stressing early detection of prostate cancer in communication to Black men (Drake et al., 2010; Griffith et al., 2007; Kripalani et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2014; Odedina, Campbell, LaRose-Pierre, Scrivens, & Hill, 2008; Wray et al., 2011). In particular, participants in Griffith et al.’s (2007) study said that Black men need to know that early detection gives them options and that having prostate cancer does not mean losing control over one’s life. These focus group interviewees suggested that prostate cancer messages should highlight options that enable men receiving prostate cancer treatment to maintain active sex lives.

A recurring theme among the studies was the need to address Black men’s concerns that prostate cancer screening via the DRE and/or a prostate cancer diagnosis threaten men’s sexuality. Both focus group and survey participants noted that prostate cancer messages need to confront fears that undergoing the DRE reduces one’s “manhood,” as well as dealing with fears that undergoing prostate cancer treatment will result in a loss of sexual ability (Fraser et al., 2009; Griffith et al., 2007; Odedina et al., 2008). Black men and women participating in one study believed that presenting men with a detailed and thorough explanation for the DRE—particularly from the perspective of men who had been screened with a DRE—would reduce men’s objections to this procedure (Griffith et al., 2007).

Another recurring message across the studies was that prostate cancer messages should be couched in terms of empowerment and should encourage men’s “ownership” of the disease (Bryan et al., 2008; Friedman, Corwin, Rose, & Dominick, 2009; Griffith et al., 2007; Odedina et al., 2008; Underwood, 1992; Wray et al., 2011). A related idea was that prostate cancer messages should stress recovery and the likelihood of survival (Bryan et al., 2008; Marks et al., 2004). For that reason, some studies suggested that prostate cancer communication should include “testimonials” from prostate cancer survivors (Ford et al., 2006; Fyffe et al., 2008; Powell et al., 1995; Wray et al., 2009).

Cultural tailoring and framing

At least two studies suggested putting prostate cancer information into the context of men’s spiritual beliefs. Holt et al. (2009) developed educational booklets aimed at increasing prostate cancer screening among Black men who attended church and then pilot-tested them with two focus groups and individual interviews. Focus group participants reacted positively to the spiritual content but believed it should be presented more clearly and earlier in the booklet (Holt et al., 2009). A previous study by Blocker et al. (2006) identified spiritual beliefs and church support as key factors in decision-making about screening and other health behaviors, suggesting that prostate cancer communication can be more effective if the messages are at least congruent with spiritual beliefs. This idea is certainly consistent with findings indicating high credibility for prostate cancer information distributed through or presented in churches (Friedman, Corwin, Rose et al., 2009; Powell et al., 1995).

Prostate cancer communication is significantly more likely to improve knowledge and influence screening intentions when the material has been tailored specifically to a Black audience. A 2009 systematic review of 40 studies testing the impact of tailoring on cancer risk perceptions, knowledge and screening behaviors revealed that tailoring is most effective when the materials provided are adapted based on behavioral characteristics, including attitudes, intentions, stage of change, and so on, rather than on risk factors such as family history and cultural characteristics (Albada, Ausems, Bensing, & van Dulmen, 2009). However, the authors did not recommend against tailoring based on risk factors or cultural characteristics, but instead suggested that communication interventions work better when messages can be adjusted based on multiple risk, cultural and behavioral characteristics. It is also worth noting that only one of the 40 studies examined in this review dealt with prostate cancer (Albada et al., 2009).

A 2016 study compared the impact of two decision support instruments (DSIs), one culturally tailored to Black men and the other culturally nonspecific. While exposure to both DSIs improved prostate cancer knowledge, the culturally tailored DSI was more effective in increasing intentions to be screened for prostate cancer. In addition, men exposed to the culturally tailored DSI expressed greater certainty about their decision-making (Frencher et al., 2016).

Beyond the recommendation that messages should be culturally tailored, as well as reflecting audience members’ specific behavioral characteristics, little research has examined which message strategies (e.g., use of humor, fear appeals, straightforward messages) have the greatest potential to reach Black men in regard to prostate cancer. One qualitative study offered insights about communicating prostate cancer information to Black men (Friedman, Corwin, Rose et al., 2009). Focus groups and interviews with older Black men in South Carolina revealed that, in addition to preferring interpersonal communication of prostate cancer information, the men believed messages should be clear and direct, consistent across different groups of men, and should emphasize men’s “ownership” of prostate cancer. The participants in this study stressed that messages had to be targeted to specific groups of men and that men needed to hear that prostate cancer communication is “about me” (Friedman, Corwin, Rose et al., 2009).

Another study used focus group sessions involving 49 Black men to identify the message channels and message strategies men believed would most effectively encourage other Black men to seek prostate cancer screening. These men stressed the importance of culturally sensitive messages and suggested that effective communication strategies could include “graphic and visual messages, fear messages, messages clarifying myths and misunderstandings, provision of shocking statistics about prostate cancer, provision of general information about prostate cancer, local resources for prostate cancer screening, and statistics supporting early detection.” The men also emphasized types of messages that should be avoided, including those that associated prostate cancer screening with negative outcomes, jargon-filled language and messages about the digital rectal exam that would prompt fear, embarrassment or an association with homosexuality (Odedina et al., 2004).

Discussion

The goal for this literature review was to provide a better understanding of the channels, sources and message approaches research has demonstrated to be most effective in reaching Black men with prostate cancer information. Interpersonal channels appear to be the preferred method for Black men. This is not surprising because, due to the organ it affects, prostate cancer discussions require sensitivity and privacy, leading Black men to prefer face-to-face communication, preferably with familiar and trusted persons.

In sharing prostate cancer information with Black men, it is also crucial to choose the right communication setting. This comprehensive review identified that Black men prefer settings such as barbershops, churches and fraternal/Black men’s organizations. Researchers have used the Black-owned barbershop, often referred to as the “Black men’s country club,” for prostate cancer education interventions. It offers several advantages for health interventions, including geographical access, access to socioeconomically diverse Black men, and a perfect environment in which to discuss diverse issues. Similarly, the church setting is often used for health interventions due to the role of the Black church in creating change in Black lives and communities. In addition to offering spiritual guidance, Black pastors are now promoting healthy behavior based on the idea that “Our bodies are the temples of God, and we need to take care of them.” This focus in the Black church is not surprising, given the significant health disparities experienced by Blacks and how those disparities have negatively impacted the health and wealth of the Black community.

The preferred sources for prostate cancer information were identified to be community doctors, wives/girlfriends, pastors, barbers and prostate cancer survivors. The emphasis on hearing about prostate cancer from trusted and familiar sources likely reflects a lingering tendency within the Black community to distrust the health-care system and particularly medical research (Brandon, Isaac, & LaVeist, 2005; Kim, Tanner, Foster, & Kim, 2015; Musa, Schulz, Harris, Silverman, & Thomas, 2009; Owens et al., 2013; Scharff et al., 2010). It also makes sense in the context of Black men’s preference for interpersonal communications.

It is, however, critical that we find other ways beyond word-of-mouth to share prostate cancer information with Black men as many Black men do not have a regular physician and are less likely than Whites to have a usual source of care (Mahmoudi & Jensen, 2013; Shi, Chen, Nie, Zhu, & Hu, 2014). Fortunately, the findings of this review suggest that Black men are also open to receiving prostate cancer information through audio and video channels, especially when the sources used include familiar figures. Especially encouraging is their openness to text messages, which will allow the rapid delivery of prostate cancer information to Black men. The use, acceptability and impact of text messages as a health communication channel for Black men needs further study.

The findings on communication content confirmed that Black men want and need comprehensive prostate cancer information, especially information that emphasizes the benefits of early detection and the likelihood of positive outcomes for men whose cancers are detected early and treated appropriately. In addition, the studies reviewed here stressed the importance of messages reassuring men that neither the screening tests for prostate cancer (especially the DRE) nor treatment of cancer necessarily threaten their sexuality or sexual performance ability. An additional finding of note is the importance of appropriate cultural tailoring of messages. Several studies stressed the value of situating prostate cancer communication in the context of Black men’s spiritual beliefs, a finding further reinforced by the many studies that identified the Black church or Black pastors as appropriate locations or sources for prostate cancer communication.

Another critical finding of this literature review is the importance of helping Black men to understand how researchers protect clinical trial participants, how their participation may benefit them and their communities. This review suggests that Black men want information about standard-of-care treatment and the outcomes it will produce. This is not surprising given that many Black men are reluctant to participate in clinical trials, while others may view clinical trial participation as simply not practical for them due to barriers such as distance from a research center, lack of access to transportation, physical limitations, concerns about time commitments, conflicts with other family needs, or other barriers (Ford et al., 2008; Shapiro, Schamel, Parker, Randall, & Frew, 2017). Culturally tailoring and framing information about clinical trials for Black men is very important to ensure their representation in clinical trials.

Like every study, this one had limitations. Use of additional databases such as the Cochrane database or MEDLINE might have produced additional studies for inclusion; however, given the relative consistency of the findings in the studies examined, it seems unlikely that these additions would have resulted in significantly different conclusions. Including studies focused solely on patient–provider communication would have contributed a different set of insights, but those findings would have had limited relevance given the study’s focus on identifying prostate cancer communication channels beyond word-of-mouth. As noted earlier, given the fact that many Black men do not have a regular physician, health promotion efforts cannot rely solely on patient–provider interactions to communicate prostate cancer prevention information to this population.

Conclusions

Reducing the disproportionate burden of prostate cancer borne by Black men will require continued efforts to make information on prostate cancer prevention, early detection, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship and clinical trials more widely available to enable Black men to make informed decisions. These findings bring us a step closer to understanding the most effective approaches to such communication, which must incorporate trusted sources and culturally tailored messages, conveyed through channels (especially video) Black men prefer. In addition, reductions in prostate cancer disparities will require the development of more effective treatment approaches for Black men. This requires their participation in prostate cancer clinical trials. Given that distrust of the medical establishment and research in general plays a significant role in Black men’s willingness to participate in prostate cancer research (Meng, McLaughlin, Pariera, & Murphy, 2016; Robinson, Ashley, & Haynes, 1996), reducing prostate cancer disparities also will require communication efforts to educate Black men about how research specifically focused on prostate cancer among Black men benefits individual patients, their families, and the Black community overall.

PubMed generally returns results in reverse chronological order, which can lead to relevant older articles appearing further into the list of results.

This date limitation was meant to increase the likelihood that study findings related to channel use, source/spokesperson preferences and content would still be relevant to current populations.

Data Availability: The data for this study are available from the first author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Department of Defense Population Sciences Award W81XWH-15-1-0526.

ORCID iD: Kim Walsh-Childers  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0050-3359

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0050-3359

References

- Ahaghotu C., Tyler R., Sartor O. (2016). African American participation in oncology clinical trials–focus on prostate cancer: Implications, barriers, and potential solutions. Clinical Genitourinary Cancer, 14(2), 105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albada A., Ausems M. G. E. M., Bensing J. M., van Dulmen S. (2009). Tailored information about cancer risk and screening: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 77(2), 155–171. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. D., Mohllajee A. P., Shelton R. C., Drake B. F., Mars D. R. (2009). A computer-tailored intervention to promote informed decision making for prostate cancer screening among African American men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 3(4), 340–351. doi: 10.1177/1557988308325460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blocker D. E., Romocki L. S., Thomas K. B., Jones B. L., Jackson E. J., Reid L., Campbell M. K. (2006). Knowledge, beliefs and barriers associated with prostate cancer prevention and screening behaviors among African-American men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(8), 1286–1295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon D. T., Isaac L. A., LaVeist T. A. (2005). The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: Is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(7), 951–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan C. J., Wetmore-Arkader L., Calvano T., Deatrick J. A., Giri V. N., Bruner D. W. (2008). Using focus groups to adapt ethnically appropriate, information-seeking and recruitment messages for a prostate cancer screening program for men at high risk. Journal of the National Medical Association, 100(6), 674–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M. M., Tannenbaum S. L., Glück S., Hurley J., Antoni M. (2014). Participation in cancer clinical trials: Why are patients not participating? Medical Decision Making: An International Journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making, 34(1), 116–126. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13497264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Health Disparities. (n.d.). cgvFactSheet. Retrieved October 21, 2016, from https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/crchd/cancer-health-disparities-fact-sheet

- Chornokur G., Dalton K., Borysova M. E., Kumar N. B. (2011). Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. The Prostate, 71(9), 985–997. doi: 10.1002/pros.21314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke-Tasker V. A. (2002). What we thought we knew: African American males’ perceptions of prostate cancer and screening methods. ABNF Journal, 13(3), 56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobran E. K., Wutoh A. K., Lee E., Odedina F. T., Ragin C., Aiken W., Godley P. A. (2013). Perceptions of prostate cancer fatalism and screening behavior between United States-born and Caribbean-born Black males. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(3), 394–400. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9825-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine N. S., Horton D., Ungar T., Joe A. K., Ramirez P., Borrell L. (2007). Fear, knowledge, and efficacy beliefs differentially predict the frequency of digital rectal examination versus prostate specific antigen screening in ethnically diverse samples of older men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 1(1), 29–43. doi: 10.1177/1557988306293495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowart L. W., Brown B., Biro D. J. (2004). Educating African American men about prostate cancer: The barbershop program. American Journal of Health Studies, 19, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Drake B. F., Shelton R. C., Gilligan T., Allen J. D. (2010). A church-based intervention to promote informed decision making for prostate cancer screening among African American men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 102(3), 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fact SheetMEDLINE, PubMed, and PMC (PubMed Central): How are they different? (n.d.). [Fact Sheets]. Retrieved February 16, 2018, from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/dif_med_pub.html

- Ford J. G., Howerton M. W., Lai G. Y., Gary T. L., Bolen S., Gibbons M. C., … Bass E. B. (2008). Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer, 112(2), 228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford M. E., Vernon S. W., Havstad S. L., Thomas S. A., Davis S. D. (2006). Factors influencing behavioral intention regarding prostate cancer screening among older African-American men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(4), 505–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester-Anderson I. T. (2005). Prostate cancer screening perceptions, knowledge and behaviors among African American men: Focus group findings. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 16(4), 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser M., Brown H., Homel P., Macchia R. J., LaRosa J., Clare R., … Browne R. C. (2009). Barbers as lay health advocates: Developing a prostate cancer curriculum. Journal of the National Medical Association, 101(7),690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frencher S. K., Sharma A. K., Teklehaimanot S., Wadzani D., Ike I. E., Hart A., Norris K. (2016). PEP talk: Prostate education program, “cutting through the uncertainty of prostate cancer for Black men using decision support instruments in barbershops.” Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 31, 506–513. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0871-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. B., Corwin S. J., Dominick G. M., Rose I. D. (2009). African American men’s understanding and perceptions about prostate cancer: Why multiple dimensions of health literacy are important in cancer communication. Journal of Community Health, 34, 449–460. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9167-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. B., Corwin S. J., Rose I. D., Dominick G. M. (2009). Prostate cancer communication strategies recommended by older African-American men in South Carolina: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Cancer Education, 24, 204–209. doi: 10.1080/08858190902876536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. B., Thomas T. L., Owens O. L., Hébert J. R. (2012). It takes two to talk about prostate cancer: A qualitative assessment of African American men’s and women’s cancer communication practices and recommendations. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 472–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyffe D. C., Hudson S. V., Fagan J. K., Brown D. R. (2008). Knowledge and barriers related to prostate and colorectal cancer prevention in underserved Black men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 100(10), 1161–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Steed T., Uchio E., Wells C. K., Aslan M., Ko J., Concato J. (2013). “Race” and prostate cancer mortality in equal-access healthcare systems. The American Journal of Medicine, 126(12), 1084–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Mason M. A., Rodela M., Matthews D. D., Tran A., Royster M., … Eng E. (2007). A structural approach to examining prostate cancer risk for rural Southern African American men. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 18(6), 73–101. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T., Mullins C. D. (2016). Age-related racial disparities in prostate cancer patients: A systematic review. Ethnicity & Health, 22(2), 184–195. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1235682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt C. L., Wynn T. A., Southward P., Litaker M. S., Jeames S., Schulz E. (2009). Development of a spiritually based educational intervention to increase informed decision making for prostate cancer screening among church-attending African American men. Journal of Health Communication, 14(6), 590–604. doi: 10.1080/10810730903120534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik R., Parvanta S., Mello S., Freres D., Kelly B., Schwartz J. S. (2013). Effects of scanning (routine health information exposure) on cancer screening and prevention behaviors in the general population. Journal of Health Communication, 18, 1422–1435. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.798381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. D., Owens O. L., Friedman D. B., Dubose-Morris R. (2015). Innovative and community-guided evaluation and dissemination of a prostate cancer education program for African-American men and women. Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 30, 779–785. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0774-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. D., Owens O. L., Friedman D. B., Hebert J. R. (2014). An intergenerational approach to prostate cancer education: Findings from a pilot project in the southeastern USA. Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 29, 649–656. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0618-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal T., Kachroo N., Sammon J., Dalela D., Sood A., Vetterlein M. W., … Abdollah F. (2017). Racial differences in prostate-specific antigen-based prostate cancer screening: State-by-state and region-by-region analyses. Urologic Oncology, 35(7), 460.e9–460.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B., Hornik R., Romantan A., Schwartz J. S., Armstrong K., DeMichele A., Nagler R. (2010). Cancer information scanning and seeking in the general population. Journal of Health Communication, 15, 734–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B. J., Niederdeppe J., Hornik R. C. (2009). Validating measures of scanned information exposure in the context of cancer prevention and screening behaviors. Journal of Health Communication, 14, 721–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key Statistics for Prostate Cancer. (2017). Retrieved October 21, 2017, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- Kim Y. C., Moran M. B., Wilkin H. A., Ball-Rokeach S. J. (2011). Integrated connection to neighborhood storytelling network, education, and chronic disease knowledge among African Americans and Latinos in Los Angeles. Journal of Health Communication, 16, 393–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.-H., Tanner A. H., Foster C. B., Kim S. Y. (2015). Talking about health care: News framing of who is responsible for rising health care costs in the United States. Journal of Health Communication, 20(2), 123–133. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.914604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque J. S., Rivers B. M., Gwede C. K., Kambon M., Green B. L., Meade C. D. (2011). Barbershop communications on prostate cancer screening using barber health advisers. American Journal of Men’s Health, 5(2), 129–139. doi: 10.1177/1557988310365167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi E., Jensen G. A. (2013). Exploring disparities in access to physician services among older adults: 2000–2007. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(1), 128–138. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J. P., Reed W., Colby K., Dunn R. A., Mosavel M., Ibrahim S. A. (2004). A culturally competent approach to cancer news and education in an inner city community: Focus group findings. Journal of Health Communication, 9, 143–157. doi: 10.1080/10810730490425303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall S. L. (2007). Use and awareness of prostate specific antigen tests and race/ethnicity. The Journal of Urology, 177, 1475–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRoy S., Cramer E., Song H. (2014). Assessing technologies for information-seeking on prostate cancer screening by low-income men. Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews, 1, 188–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.17294/2330-0698.1039 [Google Scholar]

- Meade C. D., Calvo A., Rivera M. A., Baer R. D. (2003). Focus groups in the design of prostate cancer screening information for Hispanic farmworkers and African American men. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30, 967–975. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.967-975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J., McLaughlin M., Pariera K., Murphy S. (2016). A comparison between Caucasians and African Americans in willingness to participate in cancer clinical trials: The roles of knowledge, distrust, information sources, and religiosity. Journal of Health Communication, 21, 669–677. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1153760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses K. A., Zhao Z., Bi Y., Acquaye J., Holmes A., Blot W. J., Fowke J. H. (2017). The impact of sociodemographic factors and PSA screening among low-income Black and White men: Data from the southern community cohort study. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases, 20, 424–429. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2017.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musa D., Schulz R., Harris R., Silverman M., Thomas S. B. (2009). Trust in the health care system and the use of preventive health services by older Black and White adults. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 1293–1299. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers R. E., Chodak G. W., Wolf T. A., Burgh D. Y., McGrory G. T., Marcus S. M., … Williams M. (1999). Adherence by African American men to prostate cancer education and early detection. Cancer, 86, 88–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odedina F., Oluwayemisi A. O., Pressey S., Gaddy S., Egensteiner E., Ojewale E. O., … Martin C. M. (2014). Development and assessment of an evidence-based prostate cancer intervention programme for Black men: The W.O.R.D. on prostate cancer video. Ecancermedicalscience, 8, 460. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2014.460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odedina F. T., Campbell E. S., LaRose-Pierre M., Scrivens J., Hill A. (2008). Personal factors affecting African-American men’s prostate cancer screening behavior. Journal of the National Medical Association, 100, 724–733. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31350-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odedina F. T., Scrivens J., Emanuel A., LaRose-Pierre M., Brown J., Nash R. (2004). A focus group study of factors influencing African-American men’s prostate cancer screening behavior. Journal of the National Medical Association, 96, 780–788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie D., Egan M., Hamilton V., Petticrew M. (2005). Systematic reviews of health effects of social interventions: 2. Best available evidence: how low should you go? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 886–892. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.034199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens O. L., Jackson D. D., Thomas T. L., Friedman D. B., Hébert J. R. (2013). African American men’s and women’s perceptions of clinical trials research: Focusing on prostate cancer among a high-risk population in the South. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 24, 1784–1800. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen V. H., Armes J., Ream E. (2012). Perceptions of prostate cancer in Black African and Black Caribbean men: A systematic review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology, 21, 457–468. doi: 10.1002/pon.2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell I. J., Bock C. H., Ruterbusch J. J., Sakr W. (2010). Evidence supports a faster growth rate and/or earlier transformation to clinically significant prostate cancer in Black than in White American men, and influences racial progression and mortality disparity. The Journal of Urology, 183, 1792–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell I. J., Gelfand D. E., Parzuchowski J., Heilbrun L., Franklin A. (1995). A successful recruitment process of African American men for early detection of prostate cancer. Cancer, 75, 1880–1884. [Google Scholar]

- Price J. H., Colvin T. L., Smith D. (1993). Prostate cancer: perceptions of African-American males. Journal of the National Medical Association, 85, 941–947. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Releford B. J., Frencher S. K., Yancey A. K. (2010). Health promotion in barbershops: Balancing outreach and research in African American communities. Ethnicity & Disease, 20, 185–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins A. S., Whittemore A. S., Thom D. H. (2000). Differences in socioeconomic status and survival among White and Black men with prostate cancer. American Journal of Epidemiology, 151, 409–416. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. B., Ashley M., Haynes M. A. (1996). Attitudes of African-Americans regarding prostate cancer clinical trials. Journal of Community Health, 21, 77–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01682300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L., Dark T., Orom H., Underwood W., Anderson-Lewis C., Johnson J., Erwin D. O. (2011). Patterns of information behavior and prostate cancer knowledge among African–American men. Journal of Cancer Education, 26, 708–716. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0241-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammon J. D., Dalela D., Abdollah F., Choueiri T. K., Han P. K., Hansen M., … Trinh Q.-D. (2016). Determinants of prostate specific antigen screening among Black men in the United States in the contemporary era. The Journal of Urology, 195(4P1), 913–918. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Thompson V. L., Talley M., Caito N., Kreuter M. (2009). African American men’s perceptions of factors influencing health-information seeking. American Journal of Men’s Health, 3, 6–15. doi: 10.1177/1557988307304630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharff D. P., Mathews K. J., Jackson P., Hoffsuemmer J., Martin E., Edwards D. (2010). More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21, 879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro E. T., Schamel J. T., Parker K. A., Randall L. A., Frew P. M. (2017). The role of functional, social, and mobility dynamics in facilitating older African Americans participation in clinical research. Open Access Journal of Clinical Trials, 9, 21–30. doi: 10.2147/OAJCT.S122422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Chen C.-C., Nie X., Zhu J., Hu R. (2014). Racial and socioeconomic disparities in access to primary care among people with chronic conditions. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 27, 189–198. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.130246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Cramer E. M., McRoy S. (2015). Information gathering and technology use among low-income minority men at risk for prostate cancer. American Journal of Men’s Health, 9, 235–246. doi: 10.1177/1557988314539502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swords K., Wallen E. M., Pruthi R. S. (2010). The impact of race on prostate cancer detection and choice of treatment in men undergoing a contemporary extended biopsy approach. Urologic Oncology, 28, 280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. L., Davis J. L., Turner R. O., Johnson L., Schwartz M. D., Kerner J. F., Leak C. (2006). Educating African American men about the prostate cancer screening dilemma: A randomized intervention. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 15, 2179–2188. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. L., Turner R. O., Davis J. L., Johnson L., Schwartz M. D., Kerner J., Leak C. (2001). Improving knowledge of the prostate cancer screening dilemma among African American men: An academic-community partnership in Washington, DC. Public Health Reports (Washington, DC: 1974), 116, 590–598. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.6.590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsodikov A., Gulati R., de Carvalho T. M., Heijnsdijk E. A. M., Hunter-Merrill R. A., Mariotto A. B., … Etzioni R. (2017). Is prostate cancer different in black men? Answers from 3 natural history models. Cancer, 123, 2312–2319. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood S. (1992). Cancer risk reduction and early detection behaviors among Black men: Focus on learned helplessness. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 9, 21–31. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn0901_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner A. B., Matulewicz R. S., Tosoian J. J., Feinglass J. M., Schaeffer E. M. (2017). The effect of socioeconomic status, race, and insurance type on newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer in the United States (2004–2013). Urologic Oncology, 36, 91.e1–91.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S., List M., Sinner M., Dai L., Chodak G. (2003). Educating African-American men about prostate cancer: Impact on awareness and knowledge. Urology, 61, 308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods V. D., Montgomery S. B., Herring R. P. (2004). Recruiting Black/African American men for research on prostate cancer prevention. Cancer, 100, 1017–1025. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray R. J., McClure S., Vijaykumar S., Smith C., Ivy A., Jupka K., Hess R. (2009). Changing the conversation about prostate cancer among African Americans: Results of formative research. Ethnicity & Health, 14, 27–43. doi: 10.1080/13557850802056448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray R. J., Vijaykumar S., Jupka K., Zellin S., Shahid M. (2011). Addressing the challenge of informed decision making in prostate cancer community outreach to African American men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 5, 508–516. doi: 10.1177/1557988311411909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]