Abstract

With the recent approval of several effective and well-tolerated novel agents (NAs), including ibrutinib, idelalisib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) have more therapeutic options than ever before. The availability of these agents is both an important advance for patients but also a challenge for practicing hematologist/oncologists to learn how best to sequence NAs, both with respect to chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) and to other NAs. The sequencing of NAs in clinical practice should be guided both by an individual patient’s prognostic markers, such as FISH and immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV)-mutation status, as well as the patient’s medical comorbidities and goals of care. For older, frailer patients with lower-risk CLL prognostic markers, NA monotherapy may remain a mainstay of CLL treatment for years to come. For younger, fitter patients and those with higher-risk CLL, such as del(17p) or unmutated IGHV, combination approaches may prove to be more valuable than NA monotherapy. Trials are currently evaluating the efficacy of several such combination approaches, including NA plus anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, NA plus NA (with or without anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody), and NA plus CIT. Given the tremendous efficacy of the already approved NAs, as well as the promising data for next generation NAs, the development of well-tolerated, highly effective combination strategies with curative potential for patients with CLL has become a realistic goal.

Learning Objectives

Review data on the recently approved novel agents for CLL, including those targeting the B-cell receptor kinases, B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2, and CD20

Discuss strategies for sequencing novel agent monotherapy in different CLL patient populations

Understand current and future approaches to novel agent-based combination regimens in CLL

Introduction

Over the last few years, decades of basic research into the pathobiology of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has finally begun to bear fruit, with the development and approval of several novel agents (NAs) that have proven to be highly efficacious and generally less toxic than chemoimmunotherapy (CIT). Each of these agents was initially studied primarily as monotherapy, and now postapproval they are most often used in this fashion. The availability of these agents has given rise to numerous questions about the optimal sequence of administration in various populations of CLL patients. Moreover, given that older treatment approaches such as chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) can be highly effective in CLL, determining how best to sequence NA therapy relative to CIT is a challenge.

In the era of cytotoxic chemotherapy, we learned that combining agents with different mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping toxicities could lead to deep remission and even cure in some patients with lymphoid malignancies, such as those with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The same type of success may be possible in CLL if we can optimize combination approaches in this disease; however, the nature of such an approach remains undetermined at this time. For example, should we build on the prior success of CIT and use regimens that add an NA to CIT? Or, given the risks of infection and secondary malignancies with CIT, should we focus our efforts on devising NA-only combination regimens? Or perhaps it would be beneficial to develop both types of regimens for use in different CLL patient populations.

In this review, I will briefly summarize the data on the current CLL therapeutic toolbox, including CIT, the approved NAs, and immunotherapy approaches. Next, I will discuss an approach to sequencing NA monotherapy in various CLL patient populations. Finally, I will review NA-based combination approaches in CLL and will discuss future directions.

CLL therapeutic toolbox

Chemoimmunotherapy

For younger, fit patients with CLL who do not harbor the high-risk del(17p) abnormality, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab (FCR) remains a standard therapeutic approach used around the world. Recently, 3 independent groups have published long-term data suggesting that a significant number of patients with favorable prognostic markers [without del(17p) and with mutated IGHV] can achieve very long-term remissions and in some cases likely even cure after initial therapy with FCR. For example, the group at MD Anderson Cancer Center recently reported an update on the 300 previously untreated patients treated on the FCR300 trial and found that the PFS at 12.8 years of follow-up for IGHV-mutated patients was 53.9%.1 Although the follow-up is shorter, the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) also reported a promising PFS of 66.6% at 5 years in previously untreated IGHV-mutated patients.2 An observational, retrospective study by the Italian group reported a 5-year PFS of 58.6% in IGHV-mutated patients treated with frontline FCR.3 A common theme in all 3 of these studies is that relapses tended to be early, with many of the patients who are progression-free at 5 years going on to have prolonged disease-free survival.

Another highly effective regimen for frontline CLL treatment is bendamustine, rituximab (BR). The GCLLSG recently reported on the results of CLL10, a randomized, phase 3 trial of FCR vs BR as frontline therapy.4 Although a difference in overall survival has not yet been demonstrated, the median PFS for FCR was superior to that of BR (55.2 vs 41.7 months, P = .0003). In a post hoc analysis, this PFS benefit was most pronounced in IGHV-unmutated patients (FCR: 42.7 months, BR: 33.6 months, P = .017), but the data were not yet mature enough to demonstrate a benefit in the IGHV-mutated patients (FCR: median not reached, BR: 55.4 months, P = .089). Higher rates of cytopenias and infection were seen in the FCR arm, but these differences were not statistically significant in patients under age 65 and may have been mitigated further had white blood cell growth factor support and prophylactic antibiotics been mandated. More cases of secondary myeloid neoplasia have been observed in the FCR vs BR arm (6 vs 1), though the rate of secondary malignancies as a whole between the 2 arms was not significantly different for patients under age 65. Taken together, these results suggest that FCR should remain the standard of care for most younger CLL patients with favorable prognostics, and while BR is also a reasonable option, the data are strongest for BR as frontline treatment of older patients with favorable prognostic markers.

B-cell receptor pathway inhibition

Observations in the human disease Bruton’s agammaglobulinemia5 and, subsequently, in B-cell–deficient mice,6 along with the discovery that CLL cell survival depends heavily on the stromal microenvironment,7,8 led eventually to the development of drugs targeting the B-cell receptor (BCR) kinases, which are the critical BCR-signaling intermediaries. Although spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) was the first target pursued,9 the 2 targets that eventually led to initial drug approvals were Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) and the δ isoform of phosphinositide-3-kinase (PI3K-δ).

The first BTK inhibitor to be developed in CLL was ibrutinib (formerly PCI-32765), a potent oral, irreversible inhibitor that covalently binds to cysteine-481 of BTK.10 Ibrutinib was granted initial FDA approval for relapsed/refractory CLL in February 2014 based on the PCYC 1102 study, where about 90% of relapsed/refractory CLL patients achieved response, with equivalent response rates in those with high-risk markers, such as del(17p) and unmutated IGHV.11 With 5-year follow-up, patients with the traditionally higher-risk unmutated IGHV were found to have equivalent PFS as their mutated IGHV counterparts, a remarkable finding and the first time that equivalent PFS irrespective of IGHV mutation status has been demonstrated for any therapy in CLL.12 Based on confirmatory studies such as RESONATE showing superiority of ibrutinib over ofatumumab in the relapsed refractory setting13 and RESONATE-2 demonstrating superiority of ibrutinib over chlorambucil in the frontline setting,14 ibrutinib received full FDA approval for relapsed/refractory CLL and all del(17p) CLL in July 2014 and full FDA approval for frontline CLL treatment in March 2016. Although ibrutinib is well tolerated for most patients, there are several toxicities worth noting, some of which may be related to off-target effects of ibrutinib on ITK, TEC, EGFR, and other kinases. The most common grade 3 or higher adverse effects include hypertension (20%-23%), infections including pneumonias (6%-25%), and atrial fibrillation (5%-8%).15 Low-grade bruising and bleeding due to effects of ibrutinib on platelet function can be seen in up to 60% of patients, though grade 3 or higher bleeding is only seen in about 7% of patients. Other toxicities, including arthralgias, diarrhea, and rash, tend to be lower grade and are usually manageable with supportive care, though in some cases have led to drug discontinuation.

Most ibrutinib studies have continued the drug as monotherapy until time of progression or unacceptable toxicity. This approach has helped to identify populations where ibrutinib monotherapy is unlikely to be sufficient therapy. For example, relapsed/refractory CLL patients with del(17p) have a relatively short PFS on ibrutinib monotherapy of about 26 months,12 and there are data to suggest that complex karyotype may be an even more important predictor of short duration of response to ibrutinib.16 These populations remain a major unmet need, as ibrutinib monotherapy is unlikely to provide durable remission for most such patients. Thus, although ibrutinib’s broad approval has helped to make the drug accessible to a wide range of CLL patients, it remains to be seen whether ibrutinib-based combinations will be an even more efficacious strategy, particularly for high-risk patients unlikely to benefit from CIT and for frail and/or elderly patients unlikely to tolerate CIT.

Idelalisib (formerly CAL-101/GS-1101) is a selective and potent oral inhibitor of PI3K-δ that was initially found in a phase 1 study in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory CLL to induce response in 72% of patients, with a median PFS of 32 months for those patients treated at the eventual approved dose.17 Notable grade 3 or higher toxicities in the phase 1 study included pneumonias (20%), diarrhea (6%), and transaminitis (2%). A large phase 3 study demonstrated the superiority of idelalisib plus rituximab to rituximab alone for relapsed/refractory CLL and led to the FDA approval of this regimen in July 2014.18 When idelalisib was studied in the frontline setting, significantly higher rates of toxicity proved to be prohibitive for this patient population. For example, in a frontline study of combination idelalisib with the anti-CD20 antibody ofatumumab, grade 3 or higher transaminitis was observed in 54% of patients, with grade 3 or higher colitis (17%) and pneumonitis (8%) also observed.19 Furthermore, last year, 6 clinical trials of idelalisib in combination with other agents in earlier lines of therapy were stopped due to the high incidence of toxicities, including decreased overall survival in the idelalisib-containing arms due mainly to infectious complications. Thus, although idelalisib remains an active agent with utility in the relapsed/refractory setting, it will be challenging to develop the drug further for frontline CLL treatment.

Bcl-2 family antagonism

Venetoclax (formerly ABT-199/GDC-0199) is a highly potent and specific oral antagonist of Bcl-2, an antiapoptotic protein that most CLL cells rely on heavily for survival. The first 3 CLL patients treated with venetoclax (at what later proved to be a high starting dose) had dramatic reductions in their circulating lymphocyte counts and lymphadenopathy, but also showed laboratory evidence of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS).20 The phase 1 first-in-human study in relapsed/refractory CLL was therefore modified to include a lower starting dose, weekly intrapatient dose ramp-up, and careful prophylaxis and monitoring for TLS. Despite these initial modifications, 3 cases of clinical TLS were subsequently observed in this study, including 1 patient death, leading to further modifications to start at an even lower dose. After an analysis of TLS risk factors, patients were risk-stratified into low, medium, or high TLS risk based on lymph node bulk and absolute lymphocyte count, and this categorization determined the intensity of TLS monitoring and prophylaxis. In a safety expansion cohort of 60 patients treated under this revised protocol, no further TLS events were observed.21 In the 116 total patients in this study, most of whom were heavily pretreated and had high-risk disease, venetoclax monotherapy led to an overall response rate of 79%, including a CR rate of 20%. Venetoclax was subsequently evaluated in a phase 2 study in 107 patients with relapsed/refractory del(17p) CLL, and the 79% overall response rate was nearly identical to that seen in the phase 1 study, with an estimated 12-month PFS of 72%.22 Venetoclax received accelerated FDA approval for relapsed/refractory del(17p) CLL in April 2016, with subsequent approval in Europe and elsewhere. Patients starting on venetoclax must be risk-stratified for TLS based on lymph node size and absolute lymphocyte count, and appropriate measures must be implemented for TLS prophylaxis, monitoring, and treatment, with the intensity of such interventions being commensurate with the level of risk for TLS.

Immunologic approaches

A number of different immunologic approaches are now being used or under evaluation in CLL. To build on the success of the Type I monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, obinutuzumab (formerly GA-101) was developed as a Type II, glycoengineered anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and ability to directly kill CLL cells.23 In CLL11, a randomized phase 3 study of frontline obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil vs rituximab plus chlorambucil vs chlorambucil alone, patients in the obinutuzumab-containing arm had significantly higher rates of overall and complete response, including about a 20% rate of bone marrow minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity in the subset who were tested and a PFS of about 27 months, leading to FDA approval for frontline CLL.24 With longer follow-up, the time to next treatment after the obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil regimen was about 48 months.25 Despite these advantages, an overall survival benefit has not been demonstrated for obinutuzumab in this study to date, so the decision to use it instead of rituximab should be balanced by the somewhat higher rate of significant infusion reactions and neutropenia seen with obinutuzumab. Ofatumumab, a type I, humanized monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, was also recently approved in combination with chlorambucil for frontline CLL treatment based on similar results seen in the COMPLEMENT-1 study.26 Thus, anti-CD20 plus chlorambucil regimens are good frontline options for older, frailer CLL patients, though patients should be counseled about the risk of significant infusion reactions, which can be mitigated but not eliminated by the use of steroid and antihistamine premedication.

Sequencing novel agent monotherapy

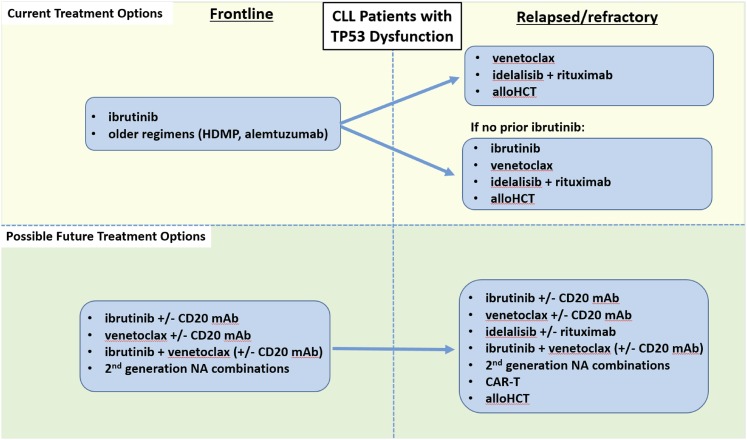

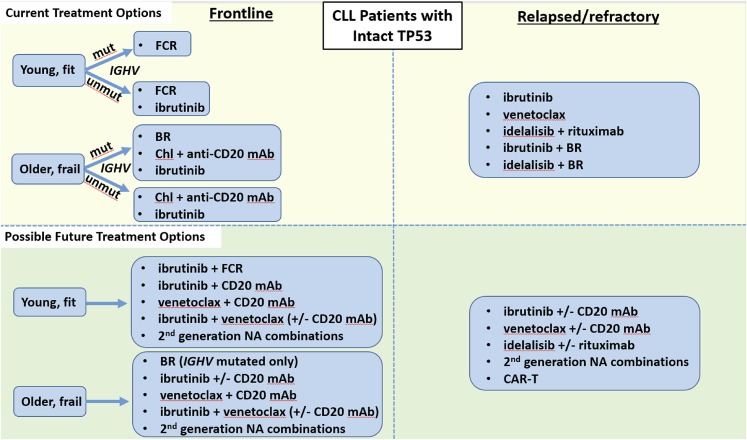

Given the plethora of effective therapies for CLL, the optimal sequence of novel agents in this disease is a complex question that cannot be completely answered with existing data. As such, participation in clinical trials is now as important as ever for CLL patients in both the frontline and relapsed/refractory treatment settings. A recent retrospective study of 178 CLL patients treated with kinase inhibitor (KI) therapy at several academic institutions found that of the patients who discontinued KI therapy, about half did so due to toxicity, about a third due to CLL progression, and 8% due to Richter’s Syndrome.27 Initial KI choice did not impact OS, and about half of patients who progressed on an initial KI responded to a subsequent KI, with a median PFS on the subsequent KI of about 1 year. A follow-up study in a larger cohort of 683 CLL patients found that those treated with ibrutinib (vs idelalisib) as first KI had a significantly better PFS in all settings, and that in patients progressing on first KI, use of a different NA had a superior PFS compared with use of CIT.28 These initial retrospective studies are a helpful starting point, but prospective data are urgently needed to help guide clinicians in the sequence of NA administration. Because CLL is a biologically heterogeneous disease, the optimal sequence of therapies must be individualized based both on prognostic markers and patient comorbidities. One useful approach to help decide on an initial sequence of NAs is to categorize patients as either having TP53 dysfunction [i.e., del(17p) and/or TP53 mutation], as summarized in Figure 1, or intact TP53, as summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Current and possible future treatment options for CLL patients with TP53 dysfunction. HDMP, high-dose methylprednisolone; alloHCT, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NA, novel agent.

Figure 2.

Current and possible future treatment options for CLL patients with intact TP53. Chl, chlorambucil.

Patients with TP53 dysfunction

Frontline

For CLL patients with TP53 dysfunction, at least 3 lines of reasoning support the use of ibrutinib monotherapy as initial treatment. First, a cohort of 35 previously untreated patients with del(17p) and/or TP53-mutated CLL were included in an investigator-initiated trial at the National Institutes of Health, where the ORR was 97%, and 91% of patients were still progression-free at 24 months.29 Second, one can extrapolate to the frontline setting from the high level of activity of ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory del(17p) CLL, where overall response rates are in the range of 90%, and the median PFS was found to be 26 months.12 Third, the durability of response with CIT in this population is known to be far shorter than this, approximately 1 year. As such, CIT should generally not be used to treat patients with del(17p) and/or TP53-mutated CLL.

Although most patients tolerate ibrutinib well, certain patients with significant cardiac comorbidities or high bleeding risk may opt to avoid ibrutinib as initial therapy. Data for alternative NA-based frontline approaches for such patients are currently scant. Although idelalisib does have frontline approval in Europe for (del17p) CLL, the significantly increased risk of toxicities, including autoimmune complications and serious infections, makes it difficult to recommend the drug in the frontline setting. Although venetoclax is expected to be active in frontline treatment of del(17p) CLL based on its activity in relapsed del(17p), prospective data are currently lacking, as the drug is currently being evaluated in ongoing frontline combination studies. Obinutuzumab monotherapy is active in the frontline setting, with 1 study showing overall response rates in the range of 49% to 67%, although only 10% of patients had del(17p).30 None of the 4 patients with del(17p) treated at 1,000 mg achieved response, whereas all 4 treated at 2000 mg did, suggesting that obinutuzumab dose may be important in this population. Other therapeutic considerations include older approaches such as high-dose methylprednisolone plus rituximab,31 alemtuzmab,32 or regimens that combine these 2 approaches.33,34

Relapsed/refractory

Relapsed/refractory CLL patients with TP53 dysfunction fall into 2 main categories, those who are ibrutinib-naïve and those who have progressed on ibrutinib. For the ibrutinib-naïve population, who have typically had prior CIT, consideration can be given to utilizing any of the 3 approved NA options, ibrutinib, venetoclax, or idelalisib (with rituximab). Based on currently available prospective data, ibrutinib is being used most commonly in such patients. The largest study ever to be conducted exclusively in del(17p) CLL was RESONATE-17, a phase 2 single-arm study of ibrutinib monotherapy in 145 patients with relapsed/refractory del(17p) CLL.35 At a median follow-up of 11.5 months, 83% of patients achieved overall response, and 24-month PFS was 63%. Consideration could also be given to using venetoclax rather than ibrutinib as the next therapy after initial CIT for relapsed/refractory del(17p) CLL. Indeed, as discussed above, venetoclax has similar efficacy data in this relapsed/refractory del(17p) population; however, while prospective data are now available for the efficacy of venetoclax after ibrutinib (see below), data for the efficacy of ibrutinib after progression on venetoclax are limited. A retrospective analysis reported that 5 of 8 patients with progressive CLL/SLL on venetoclax achieved PR on ibrutinib,36 but a larger, prospective dataset would be valuable to justify more routine use of venetoclax prior to ibrutinib in this population.

For the second category of CLL patients with TP53 dysfunction who have progressed on ibrutinib, there are prospective data from an ongoing phase 2 trial suggesting that venetoclax can be effective in patients with (or without) del(17p) who are progressing on ibrutinib.37 In this trial, 43 patients progressing on ibrutinib were treated with venetoclax monotherapy, and an ORR rate of 70% was observed, with 72% of patients progression-free at 1 year. Given these data, for patients with del(17p) CLL who are progressing on ibrutinib, venetoclax is the preferred next line of therapy. Consideration could also be given to idelalisib (with rituximab), although prospective efficacy data for this approach are lacking. One consideration for patients showing signs of progression on ibrutinib is to consider testing when available for the BTK C481S ibrutinib resistance mutation.38 A recent study found that 85% of patients on ibrutinib who experienced relapse had acquired BTK or PLCϒ-2 mutations, and these mutations were detected an estimated 9.3 months prior to relapse.39 The median overall survival of such patients was 22.7 months, and, as such, better options for salvage therapy for this population are needed. Ongoing studies will be needed to determine whether early intervention such as allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation or chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy40 for patients found to have such mutations but without overt signs of progression clinically will improve outcomes.

Optimal therapy in any one case also depends on the comorbidities and preferences of the individual patient. Although the majority of CLL patients have thus far received ibrutinib as their first NA therapy, certain ibrutinib-naïve patients may be better suited for other therapies. For example, those with significant cardiac comorbidities, particularly if they require anticoagulation, may opt to receive venetoclax or idelalisib with rituximab over ibrutinib in the relapsed/refractory setting after CIT. Factors in favor of using venetoclax include its ability to induce significant rates of CR including MRD negativity even as a single agent, as well as its favorable longer-term toxicity profile once the patient makes it through the initial risk of TLS. Patients on long-term venetoclax can continue to experience neutropenia, so neutrophil counts should be monitored periodically, and if severe neutropenia develops, growth factor support with filgrastim or pegfilgrastim should be provided concomitantly with treatment. Dose reduction or holding can also be used but is infrequently necessary. Patients less well-suited for venetoclax monotherapy include those with significant renal dysfunction, who are at higher risk for complications from TLS. Another option for patients with relative contraindications to ibrutinib is idelalisib with rituximab. This regimen is also highly active and is straightforward to initiate, though close monitoring does still need to occur for autoimmune toxicities and infection. Patients with a history of gastrointestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease as well those with active hepatic dysfunction including alcohol abuse, hepatitis, and/or cirrhosis are generally less well-suited for idelalisib.

Patients without TP53 dysfunction

Frontline

The options for frontline therapy in CLL patients without del(17p) are numerous. For most patients, multiple regimens would be reasonable to consider. Prognostic marker testing can be helpful in guiding clinicians toward the regimens most likely to provide durable response for a particular patient. IGHV mutation testing can be particularly helpful since, as above, several recent datasets have shown it to be a key predictor of PFS with CIT. As such, patients with mutated IGHV should be considered for a CIT-based approach. Based on the high rates of CR and MRD negativity, as well as the superior PFS seen with FCR compared with BR in the randomized phase 3 CLL10 study,4 FCR is still considered the standard of care for most younger, fit patients with IGHV-mutated CLL. BR is an appropriate frontline option for older patients with mutated IGHV, but given the lack of a plateau on its PFS curve, such patients are likely to relapse eventually. It remains undetermined at this point whether it would be better to start with ibrutinib as initial therapy for either of these patient groups. It has been well-documented that CIT can lead to clonal evolution and enrichment of higher-risk genetic abnormalities.41 On the other hand, recent reports suggest that clonal evolution may also occur on ibrutinib.42 A large, randomized phase 3 study led by ECOG of ibrutinib/rituximab vs FCR (E1912, NCT02048813) is now fully accrued and may help to answer the question of which approach is better for younger, fit patients. A large, randomized phase 3 study led by the Alliance of ibrutinib vs ibrutinib/rituximab vs BR may also help to answer this question in older, frailer patients (A041202, NCT01886872). It should be noted that given that both studies are frontline trials, it is expected to take several years before PFS data mature. Also, since neither trial stratified by IGHV status, it is possible that definitive information on therapy selection based on IGHV status will not be available even after the data from these studies do mature. Given the current evidence, treatment approaches for younger CLL patients should be individualized depending on prognostic factors, patient preference, and a balanced discussion about the short- and long-term effects of CIT vs NA-based approaches.

Although fewer than half of patients on the frontline RESONATE-2 study of ibrutinib vs chlorambucil had unmutated IGHV, nevertheless the favorable results with ibrutinib in this study do support the use of ibrutinib as initial therapy for older patients with unmutated IGHV.14 For frailer old patients, chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab24 or chlorambucil plus ofatumumab26 can be considered for patients irrespective of IGHV mutation status. How should one decide between starting with ibrutinib vs starting with one of the chlorambucil/anti-CD20 antibody regimens? Since head-to-head data do not exist, it is reasonable to discuss the pros/cons of both regimens with patients. Patients desiring a well-tolerated oral regimen who do not mind long-term continuous therapy, have adequate insurance coverage, and are likely to be adherent to oral therapy in the long term are good candidates for ibrutinib. In contrast, those with active cardiac or bleeding issues, those who prefer time-limited therapy, and those with more difficulty accessing or adhering to ibrutinib therapy long term may be better suited to starting with chlorambucil/anti-CD20 therapy.

Relapsed/refractory

For patients without TP53 dysfunction who relapse after or are refractory to frontline therapy, it is important to repeat FISH testing, as clonal evolution enriches relapsed/refractory patients for high-risk abnormalities.43 Where available, targeted sequencing of the TP53 gene should also be performed. Assuming that such testing does not reveal the acquisition of TP53 dysfunction, the second-line treatment of choice depends on whether ibrutinib was used in the frontline setting. For patients who started with ibrutinib and then progressed, there are currently no data on whether CIT is effective in this population. It is reasonable to consider using a different NA in such patients. As above, the most robust prospective data in this population are for venetoclax,37 but consideration can also be given to idelalisib (with rituximab), which is another reasonable option.

For patients without TP53 dysfunction who relapse after initial CIT, a decision about whether to switch to a novel agent vs repeat CIT depends on both the depth and duration of the initial remission and the patient’s preference about chronic oral therapies. For patients who had a long initial remission after CIT (typically at least 2-3 years), continue to have low-risk biology, and desire time-limited therapy, consideration can be given to repeating CIT. However, such patients should be counseled that the expected remission duration after a second round of CIT is likely to be shorter than the first, the risk of clonal evolution may increase, and the risk of infectious complications and secondary malignancies such as MDS/AML may increase. As such, most patients who relapse after CIT, even those who have had a long initial remission, should be considered for an NA-based approach in the second line. The sequencing of NAs in this population should be similar to the approach described above for relapsed/refractory, ibrutinib-naive patients with TP53 dysfunction.

Another question is whether there is utility to adding an NA to CIT in the relapsed/refractory setting. Two recent large, randomized phase 3 trials have provided data on this question. The HELIOS study randomized patients to ibrutinib plus BR (iBR) vs placebo plus BR and found that the estimated 18-month PFS for the ibrutinib arm was significantly higher than for BR alone (79% vs 24%), though patients in the ibrutinib containing arm did have some additional toxicities associated with ibrutinib.44 A similar study randomized patients to idelalisib plus BR vs placebo plus BR, and at a median of 14 months of follow-up, the median PFS in the idelalisib arm was 20.8 vs 11 months in the BR-alone arm.45 The rates of serious adverse events and infections were higher in the idelalisib arm. Given the additional toxicities inherent in adding an NA to CIT, an open question remains whether this approach is superior to NA monotherapy alone, and neither of these 2 trials was designed to answer that crucial question. Although one must be cautious in comparing across studies, the estimated PFS at 30 months for ibrutinib monotherapy in the phase 2 relapsed/refractory population of 69%15 is comparable to the 79% rate at 18 months seen with ibrutinib + BR in the HELIOS study. Thus, until randomized data are available demonstrating the superiority of chemotherapy plus NA over NA alone for relapsed/refractory CLL, it is difficult to recommend the chemotherapy plus NA regimens over NA alone for most patients.

Novel agent–containing combination therapies in CLL

While NA monotherapy will likely remain an important treatment option for older, less fit CLL patients, this approach is suboptimal for younger, fit patients. Long-term monotherapy with any of the NAs has been shown to lead to resistance in high-risk CLL patients, such as the previously mentioned C481S BTK mutation in patients on ibrutinib.39,46 Other issues include limited durability of response in CLL patients with del(17p) and/or complex karyotype, decreased adherence over time with chronic oral therapies, and the costs of potentially decades of NA use in younger patients with lower-risk CLL. As such, there is tremendous value in developing combination regimens for younger, fit CLL patients. Given the potential for durable benefit from such approaches, utilizing MRD status as a surrogate for PFS and OS is a practical approach to assessing efficacy as efficiently as possible.47 Time-limited, NA-containing combination regimens may allow patients to take advantage of the clear benefits associated with NA therapy without the commitment to an ongoing chronic oral therapy. A comprehensive review of NA-based combination approaches in CLL is beyond the scope of this review. As such, 3 illustrative approaches currently under investigation will be discussed.

Novel agent plus anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody combinations

Early in its development, venetoclax was evaluated preclinically with rituximab, and the combination was found to be highly effective through enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, among other mechanisms.20 This led to a phase 1b study of venetoclax plus rituximab in 49 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL.48 The combination was well tolerated, with similar toxicities as are seen with venetoclax monotherapy, though with slightly higher neutropenia rates. The efficacy data of the venetoclax/rituximab combination were promising, with 86% of patients achieving response overall, including 51% with CR/CRi, leading to 82% of patients being progression-free at 2 years. Bone marrow MRD negativity by flow cytometry (sensitivity 10−4) was seen in 57% of patients. Intriguingly, 13 responders elected to discontinue venetoclax, and of the 10 patients currently still being followed, all 8 who were MRD-negative remain in ongoing remission after a median of 9.7 months off venetoclax. The depth of responses in this study, including high rates of CR and MRD negativity, provide evidence suggesting that time-limited therapy with this type of approach may be possible. A confirmatory randomized, phase 3 registration study of a 2-year course of venetoclax plus rituximab vs a standard course of bendamustine plus rituximab in relapsed/refractory CLL is now fully accrued (MURANO, NCT02005471). If positive, this study would suggest that venetoclax plus rituximab is an attractive option for relapsed/refractory CLL patients who desire a time-limited, chemotherapy-free treatment approach. A similar approach is being studied in the frontline setting in the CLL14 study, a randomized, phase 3 trial comparing 1 year of obinutuzumab/venetoclax to obinutuzumab/chlorambucil in previously untreated, older patients with CLL (NCT02242942). This study is also now fully accrued, and an early report on the 13 patients in the safety run-in phase was recently published.49 The obinutuzumab/venetoclax combination was generally well-tolerated, and 7/12 patients achieved CR/CRi, with 11/12 MRD-negative in the blood. Ibrutinib and idelalisib have also been studied in combination with rituximab with promising results,18,50 although it remains unclear at this time how much incremental clinical benefit, if any, the addition of the antibody to a BCR pathway inhibitor provides.

Novel–novel combinations

With several NAs already approved in CLL and several more in development, it is not practical to perform clinical trials of every possible combination. As such, studying combinations of agents with distinct mechanisms of action, nonoverlapping toxicities, and sound preclinical data should be prioritized. One particularly promising combination is ibrutinib plus venetoclax. This 2-drug combination was previously shown to kill primary CLL cells effectively ex vivo.51 Using BH3 profiling, a functional assay to assess the effects of these agents on mitochondria, our group recently found that these 2 drugs have distinct effects on CLL cell mitochondria.52 Whereas venetoclax increases the propensity for CLL cells to undergo apoptosis (what we call mitochondrial priming), ibrutinib causes CLL cells to selectively become more dependent on BCL-2 for their survival. These complementary effects likely underlie the potent CLL cell-killing that is observed with the combination of these 2 drugs ex vivo. Several clinical trials are already underway evaluating this combination, including a phase 2 study in previously untreated CLL (NCT02756897) and 2 separate phase 2 studies looking at the 3-drug combination of venetoclax, ibrutinib, and obinutuzumab in previously untreated patients with del(17p) CLL (NCT02758665) or in CLL patients in all cytogenetic risk groups (NCT02427451).

Adding novel agents to chemoimmunotherapy

While the prospect of time-limited NA-only combination approaches to provide durable remission in CLL is an exciting one, it should be noted that the only conventional therapy thus far that has consistently proven to have curative potential for the subset of younger, fit CLL patients with mutated IGHV is FCR. As such, rather than abandoning CIT completely, another approach under investigation is to combine NA therapy with CIT. One study looked at ibrutinib in combination with CIT in relapsed/refractory CLL.53 Thirty patients were treated with ibrutinib plus BR for up to 6 cycles, with ibrutinib subsequently continued until disease progression or toxicity. The ORR was 93%, including 5 patients with CR, 3 patients with nodal PR, and a 1 year PFS of 90%. Also included in this study were 3 patients who received ibrutinib plus FCR. All 3 patients tolerated this combination well and achieved CR, including 2 with bone marrow MRD negativity. This led to the development of a phase 2 study of ibrutinib plus FCR (iFCR) for previously untreated younger, fit patients with CLL.54 Patients are treated with up to 6 cycles of ibrutinib given concurrently with FCR, followed by at least 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance. Patients who are MRD-negative in the bone marrow after 2 years of maintenance then discontinue ibrutinib. This approach has been well-tolerated and thus far has a rate of CT-confirmed CR with bone marrow MRD negativity of 39%, which compares favorably to the 20% rate observed historically with FCR alone in the CLL8 trial.55 Moreover, 89% of patients on iFCR achieved MRD negativity in the marrow, including 76% of patients who achieved PR, most of whom had small residual lymph nodes. In addition to seeing whether the rate of durable response increases in IGHV-mutated patients, the iFCR study will also provide data on whether IGHV unmutated CLL patients can also achieve durable response with a time-limited regimen.

Conclusion

Although the last few years have been an exciting time in CLL research, the next few years promise to be at least as interesting. We have reached the end of the beginning of the NA era, in that we now have several approved NAs including ibrutinib, idelalisib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab in our therapeutic toolkit. The sequence of administration of NA monotherapy should be guided by both the prognostic markers and the comorbidities of each individual patient. For older, frailer patients, NA monotherapy may remain a mainstay of CLL treatment for years to come. For younger, fit patients and those with high-risk CLL such as del(17p) or complex karyotype, rational combination approaches informed by sound preclinical data may prove to be more valuable than NA monotherapy. Trials are currently evaluating the efficacy of several such approaches, including NA plus anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, NA plus NA (with or without anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody), and NA plus CIT. Additionally, several next generation NA therapies are showing promise, such as selective BTK inhibitors like acalabrutinib56 and BGB-3111,57 PI3K inhibitors like umbralisib (formerly TGR-1202)58 and duvelisib,59 CAR-T–based therapies,60 and other immunotherapy-based approaches. NA combination regimens that use the agents with the most favorable toxicity profiles are likely to provide highly efficacious disease control while minimizing risks to patients. Given the plethora of options now in the therapeutic toolkit, active participation in clinical trials for CLL patients is now as critical as it has ever been.

A past generation of hematologist/oncologists had a unique opportunity to devise combination regimens containing cytotoxic chemotherapy that eventually led to cure in a high fraction of patients with diseases such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. With the development of highly active and well-tolerated NAs, we now have a similar opportunity in CLL. Though considerable progress has been made in the last few years to improve CLL therapy, we must not rest on our laurels. Now is the time for us to redouble our efforts and work even harder to develop highly effective, well-tolerated combination strategies with curative potential for patients with CLL.

References

- 1.Thompson PA, Tam CS, O’Brien SM, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab treatment achieves long-term disease-free survival in IGHV-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(3):303-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer K, Bahlo J, Fink AM, et al. Long-term remissions after FCR chemoimmunotherapy in previously untreated patients with CLL: updated results of the CLL8 trial. Blood. 2016;127(2):208-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossi D, Terzi-di-Bergamo L, De Paoli L, et al. Molecular prediction of durable remission after first-line fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;126(16):1921-1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Bahlo J, et al. ; international group of investigators; German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL10): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):928-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchinson JH. Congenital agammaglobulinaemia. Lancet. 1955;269(6895):844-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osmond DG, Rico-Vargas S, Valenzona H, et al. Apoptosis and macrophage-mediated cell deletion in the regulation of B lymphopoiesis in mouse bone marrow. Immunol Rev. 1994;142:209-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burger JA, Tsukada N, Burger M, Zvaifler NJ, Dell’Aquila M, Kipps TJ. Blood-derived nurse-like cells protect chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells from spontaneous apoptosis through stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood. 2000;96(8):2655-2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burger JA, Ghia P, Rosenwald A, Caligaris-Cappio F. The microenvironment in mature B-cell malignancies: a target for new treatment strategies. Blood. 2009;114(16):3367-3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedberg JW, Sharman J, Sweetenham J, et al. Inhibition of Syk with fostamatinib disodium has significant clinical activity in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(13):2578-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honigberg LA, Smith AM, Sirisawad M, et al. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(29):13075-13080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Five-year experience with single-agent ibrutinib in patients with previously untreated and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia. 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, 2016. Abstract 233. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. ; RESONATE Investigators. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):213-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. ; RESONATE-2 Investigators. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2425-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125(16):2497-2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson PA, O’Brien SM, Wierda WG, et al. Complex karyotype is a stronger predictor than del(17p) for an inferior outcome in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with ibrutinib-based regimens. Cancer. 2015;121(20):3612-3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown JR, Byrd JC, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p110δ, for relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123(22):3390-3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):997-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lampson BL, Kasar SN, Matos TR, et al. Idelalisib given front-line for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia causes frequent immune-mediated hepatotoxicity. Blood. 2016;128(2):195-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat Med. 2013;19(2):202-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with Venetoclax in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):311-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, et al. Venetoclax in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):768-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mössner E, Brünker P, Moser S, et al. Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct and immune effector cell-mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood. 2010;115(22):4393-4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1101-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goede V, Fischer K, Engelke A, et al. Obinutuzumab as frontline treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: updated results of the CLL11 study. Leukemia. 2015;29(7):1602-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillmen P, Robak T, Janssens A, et al. ; COMPLEMENT 1 Study Investigators. Chlorambucil plus ofatumumab versus chlorambucil alone in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (COMPLEMENT 1): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1873-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mato AR, Nabhan C, Barr PM, et al. Outcomes of CLL patients treated with sequential kinase inhibitor therapy: a real world experience. Blood. 2016;128(18):2199-2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mato AR, Hill BT, Lamanna N, et al. Optimal sequencing of ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a multi-center study of 683 patients. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(5):1050-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farooqui MZ, Valdez J, Martyr S, et al. Ibrutinib for previously untreated and relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with TP53 aberrations: a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):169-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrd JC, Flynn JM, Kipps TJ, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of obinutuzumab monotherapy in symptomatic, previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(1):79-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castro JE, James DF, Sandoval-Sus JD, et al. Rituximab in combination with high-dose methylprednisolone for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(10):1779-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stilgenbauer S, Zenz T, Winkler D, et al. ; German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. Subcutaneous alemtuzumab in fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical results and prognostic marker analyses from the CLL2H study of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(24):3994-4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pettitt AR, Jackson R, Carruthers S, et al. Alemtuzumab in combination with methylprednisolone is a highly effective induction regimen for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and deletion of TP53: final results of the national cancer research institute CLL206 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1647-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davids MS, Kim HT, Fernandes S, et al. A phase II study of ofatumumab-high dose methylprednisolone followed by ofatumumab-alemtuzumab in 17p deleted or tp53 mutated CLL [abstract]. Blood. 2015;126: Abstract 4159. [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Brien S, Jones JA, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion (RESONATE-17): a phase 2, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):1409-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lew T, Anderson M.A., Tam C.S., Huang D.C.S., Juneja S. . Clinicopathological Features and Outcomes of Progression for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL) Treated with the BCL2 Inhibitor Venetoclax. 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, 2016. Abstract 3223.

- 37.Jones J. CMY, Mato, A.R., Furman, R.R., Davids, M.S., et al. Venetoclax (VEN) Monotherapy for Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Who Relapsed after or Were Refractory to Ibrutinib or Idelalisib. 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, 2016. Abstract 637. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woyach JA, Bojnik E, Ruppert AS, et al. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) function is important to the development and expansion of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. 2014;123(8):1207-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Guinn D, et al. BTK(C481S)-mediated resistance to ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(13):1437-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turtle CJ, Hay KA, Hanafi LA, et al. Durable molecular remissions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with cd19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells after failure of ibrutinib. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(26):3010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landau DA, Carter SL, Stojanov P, et al. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell. 2013;152(4):714-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burger JA, Landau DA, Taylor-Weiner A, et al. Clonal evolution in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia developing resistance to BTK inhibition. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landau DA, Tausch E, Taylor-Weiner AN, et al. Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature. 2015;526(7574):525-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chanan-Khan A, Cramer P, Demirkan F, et al. ; HELIOS investigators. Ibrutinib combined with bendamustine and rituximab compared with placebo, bendamustine, and rituximab for previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma (HELIOS): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):200-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zelenetz AD, Barrientos JC, Brown JR, et al. Idelalisib or placebo in combination with bendamustine and rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: interim results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):297-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn IE, Underbayev C, Albitar A, et al. Clonal evolution leading to ibrutinib resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129(11):1469-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rawstron AC, Böttcher S, Letestu R, et al. ; European Research Initiative in CLL. Improving efficiency and sensitivity: European Research Initiative in CLL (ERIC) update on the international harmonised approach for flow cytometric residual disease monitoring in CLL. Leukemia. 2013;27(1):142-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seymour JF, Ma S, Brander DM, et al. Venetoclax plus rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(2):230-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Fink AM, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129(19):2702-2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jain P, Keating MJ, Wierda WG, et al. Long-term follow-up of treatment with ibrutinib and rituximab in patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(9):2154-2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cervantes-Gomez F, Lamothe B, Woyach JA, et al. Pharmacological and protein profiling suggests venetoclax (ABT-199) as optimal partner with ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(16):3705-3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng J, Isik E, Fernandes SM, Brown JR, Letai A, Davids MS. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibition increases BCL-2 dependence and enhances sensitivity to venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia [published online ahead of print 14 February 2017]. Leukemia. doi:10.1038/leu.2017.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown JR, Barrientos JC, Barr PM, et al. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib with chemoimmunotherapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(19):2915-2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davids MS, Kim HT, Brander DM, et al. Initial results of a multicenter, phase II study of ibrutinib plus FCR (iFCR) as frontline therapy for younger CLL patients. 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, 2016. Abstract 3243. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. ; International Group of Investigators; German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byrd JC, Harrington B, O’Brien S, et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196) in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):323-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tam CS, Opat S, Cull G, et al. Twice daily dosing with the highly specific BTK inhibitor, Bgb-3111, achieves complete and continuous BTK occupancy in lymph nodes, and is associated with durable responses in patients (pts) with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, 2016. Abstract 642. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davids MS, Kim HT, Nicotra A, et al. TGR-1202 in combination with ibrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory CLL or MCL: preliminary results of a multicenter phase I/Ib study. 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, 2016. Abstract 641. [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Brien S, Patel M, Kahl BS, et al. Duvelisib (IPI-145), a PI3K-δ,γ inhibitor, is clinically active in patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124: Abstract 3334. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Porter DL, Hwang WT, Frey NV, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(303):303ra139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]