Abstract

Enterococcus faecium E35048, a bloodstream isolate from Italy, was the first strain where the oxazolidinone resistance gene optrA was detected outside China. The strain was also positive for the oxazolidinone resistance gene cfr. WGS analysis revealed that the two genes were linked (23.1 kb apart), being co-carried by a 41,816-bp plasmid that was named pE35048-oc. This plasmid also carried the macrolide resistance gene erm(B) and a backbone related to that of the well-known Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pRE25 (identity 96%, coverage 65%). The optrA gene context was original, optrA being part of a composite transposon, named Tn6628, which was integrated into the gene encoding for the ζ toxin protein (orf19 of pRE25). The cfr gene was flanked by two ISEnfa5 insertion sequences and the element was inserted into an lnu(E) gene. Both optrA and cfr contexts were excisable. pE35048-oc could not be transferred to enterococcal recipients by conjugation or transformation. A plasmid-cured derivative of E. faecium E35048 was obtained following growth at 42°C, and the complete loss of pE35048-oc was confirmed by WGS. pE35048-oc exhibited some similarity but also notable differences from pEF12-0805, a recently described enterococcal plasmid from human E. faecium also co-carrying optrA and cfr; conversely it was completely unrelated to other optrA- and cfr-carrying plasmids from Staphylococcus sciuri. The optrA-cfr linkage is a matter of concern since it could herald the possibility of a co-spread of the two genes, both involved in resistance to last resort agents such as the oxazolidinones.

Keywords: multiresistance plasmid, optrA gene, cfr gene, oxazolidinone resistance, Enterococcus faecium

Introduction

Enterococci are members of the gut microbiota of humans and many animals, and are widespread in the environment. They are also major opportunistic pathogens, mostly causing healthcare-related infections. Among the reasons of their increasing role as nosocomial pathogens, the primary factor is their inherent ability to express and acquire resistance to several antimicrobial agents, with Enterococcus faecium emerging as the most therapeutically challenging species (Arias and Murray, 2012).

Oxazolidinones are among the few agents that retain activity against multiresistant strains of enterococci (Shaw and Barbachyn, 2011; Patel and Gallagher, 2015), and the emergence of resistance to these drugs is an issue of notable clinical relevance. Particularly worrisome, due to their potential for horizontal dissemination, are the oxazolidinone resistances caused by cfr, encoding a ribosome-modifying enzyme (Kehrenberg et al., 2005; Deshpande et al., 2015; Munita et al., 2015), and optrA, encoding a ribosome protection mechanism (Wang et al., 2015; Wilson, 2016; Sharkey et al., 2016). Both these genes were found to be associated with a number of different mobile genetic elements.

The optrA gene, in particular, was discovered in China in enterococci of human and animal origin isolated in 2005-2014 (Wang et al., 2015) where it was detected in different genetic contexts (He et al., 2016). Since then, optrA-positive enterococci have been reported worldwide (Mendes et al., 2016; Cavaco et al., 2017; Freitas et al., 2017; Pfaller et al., 2017a,b), including Italy, where optrA was found — the first report outside China — in two bloodstream isolates of E. faecium which were also positive for the cfr gene, which was not expressed (Brenciani et al., 2016b). By further investigating one of those isolates (strain E35048), we noticed that both optrA and cfr were capable of undergoing excision as minicircles (Brenciani et al., 2016b). It is worth noting that among the reported optrA protein variants (Morroni et al., 2017), the one detected in E. faecium E35048, named optrAE35048, is the most divergent, differing by 21 amino acid substitutions from the firstly described optrA variant (Wang et al., 2015).

The goal of the present work was to investigate the locations, genetic environments, and transferability of the optrA and cfr resistance genes detected in E. faecium E35048. We characterized the genetic contexts and location of optrA and cfr in E. faecium E35048, and found that both genes were co-carried on a plasmid of original structure, named pE35048-oc. This plasmid, which also carried the macrolide resistance gene erm(B), shared regions of homology with the well-characterized (Schwarz et al., 2001) and widely distributed (Rosvoll et al., 2010; Freitas et al., 2016) conjugative multiresistance enterococcal plasmid pRE25, but was unable to transfer. In pE35048-oc, the genetic context of optrA was different from those so far described in other optrA-carrying plasmids, underscoring the plasticity of these resistance regions.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strain

optrA- and cfr-positive E. faecium E35048 (linezolid MIC, 4 μg/ml; tedizolid MIC, 2 μg/ml) was isolated in Italy in 2015 from a blood culture (Brenciani et al., 2016b).

WGS and Sequence Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). WGS was carried out with the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, United States) by using a 2 × 300 paired end approach and a DNA library prepared using Nextera XT DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). De novo assembly was performed with SPAdes V 3.10.0 (Bankevich et al., 2012) using default parameters. Scaffolds characterized by a length ≤ 300 bp were filtered out. Raw reads were mapped to the filtered scaffolds by using bwa (Li and Durbin, 2009) to check the quality of the assembly. Tentative ordering of selected scaffolds of plasmid origin was performed by BLASTN comparisons of data from WGS to homologous plasmids, and eventually confirmed by PCR approach followed by Sanger sequencing. The ST was determined through the Center for Genomic Epidemiology1. Analysis of insertion sequences was carried out using ISFinder online database2 (Siguier et al., 2006).

PCR Mapping Experiments

PCR mapping with outward-directed primers topo-FW (5′-GAAGCGACAAGAGCAAGTAT-3′) and optrA-RV (5′- TCTTGAACTACTGATTCTCGG-3′), and Sanger sequencing were used to close the pE35048-oc plasmid sequence.

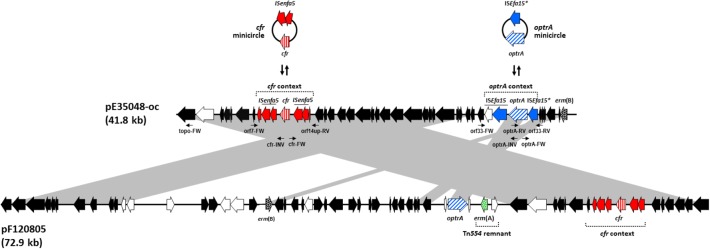

To investigate the excision of the optrA and cfr genetic contexts, PCR mapping and sequencing assays were performed using: (i) primer pairs targeting the regions flanking their insertion sites [orf7-FW (5′-ATTTTTCTTTTGATTTGGTA-3′) and orf14up-RV (5′-AAGTAATCTTTTTTTGTTTT-3′) for the cfr genetic context; and orf33-FW (5′-CTTGTTTTGGTGTTGCCCTGG-3′) and orf33-RV (5′-CCACCAAGTAAAAAAGCGG-3′) for the optrA genetic context]; (ii) outward-directed primer pairs designed from cfr and optrA genes [cfr-INV (5′-TTGATGACCTAATAAATGGAAGTA-3′) and cfr-FW (5′-ACCTGAGATGTATGGAGAAG-3′); optrA-INV (5′-TTTTTCCACATCCATTTCTACC-3′) and optrA-FW (5′-GAAAAATAACACAGTAAAAGGC-3′)] (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic, but to scale, comparative representation of the linearized forms of plasmid pE35048-oc and plasmid pEF12-0805, both co-carrying optrA and cfr and sharing a pRE25-related backbone. ORFs are depicted as arrows pointing to the direction of transcription; those common to pRE25 are black, with erm(B) spotted; the erm(A) gene, not found in pRE25, is green spotted; the ORFs of the optrA and the cfr contexts are blue and red, respectively, with optrA diagonally and cfr vertically striped. Minicircle formation by such contexts in pE35048-oc is shown above the plasmid. Other ORFs are white. The primer pairs used are indicated by thin arrows below pE35048-oc. Gray areas between ORF maps denote > 90% DNA identity.

S1-PFGE, Southern Blotting and Hybridization

Total DNA in agarose gel plugs was digested with S1 nuclease (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Milan, Italy) and separated by PFGE as previously described (Barton et al., 1995). After S1-PFGE, DNA was blotted onto positively charged nylon membrane (Ambion-Celbio, Milan, Italy) and hybridized with specific probes (Brenciani et al., 2007). cfr and optrA probes were obtained by PCR as described elsewhere (Wang et al., 2015; Brenciani et al., 2016a).

Transformation and Conjugation Experiments

Purified plasmids extracted from E. faecium E35048 were transformed into the E. faecalis JH2-2 recipient by electrotransformation as described previously (Brenciani et al., 2016a). The transformants were selected on plates supplemented with florfenicol (10 μg/ml) or erythromycin (10 μg/ml).

In mating experiments, E. faecium E35048 was used as the donor. Two florfenicol-susceptible laboratory strains were used as recipients: E. faecium 64/3 (Werner et al., 1997), and E. faecalis JH2-2, both resistant to fusidic acid. Conjugal transfer was performed on a membrane filter. Transconjugants were selected on plates supplemented with florfenicol (10 μg/ml) or erythromycin (10 μg/ml) plus fusidic acid (25 μg/ml).

Curing Assays

Enterococcus faecium E35048 was grown overnight in brain heart agar (BHA) at 42°C for some passages. After each passage a few colonies were picked up, and their DNA was extracted and screened for the presence of the optrA and cfr genes by PCR with specific primers (Brenciani et al., 2016b). In case of negative testing, the strain was regarded as possibly cured and subjected to WGS for confirmation.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The complete nucleotide sequence of plasmid pE35048-oc has been assigned to GenBank accession no. MF580438, available under the BioProject ID PRJNA481862.

Results and Discussion

Genome General Features and Resistome of E. faecium E35048

Assembly of the raw WGS data followed by filtering of low length contigs gave a total of 172 scaffolds (range: 310-137, 266 bp; N50: 41,930 bp; L50: 18; mean coverage: 92X). E. faecium E35048 was assigned to ST117, a globally disseminated hospital-adapted clone (Hegstad et al., 2014; Tedim et al., 2017). Resistome analysis revealed the presence of six acquired resistance genes in addition to the previously described optrA and cfr genes: erm(B) (resistance to macrolides, lincosamides and group B streptogramins), msr(C) (resistance to macrolides and group B streptogramins), tet(M) (resistance to tetracycline), aphA and aadE (resistance to aminoglycosides), and sat4 (resistance to streptothricin).

Characterization of the optrA- and cfr-Carrying Plasmid pE35048-oc

The optrA and cfr genes were found to be linked, 23.1 kb apart in the linearized form, on the same contig, which also contained regions of high similarity (96% nucleotide identity) to the E. faecalis plasmid pRE25 (50 kb) (65% coverage) (Schwarz et al., 2001) (GenBank accession no. NC_008445).

PCR and Sanger sequencing using outward-directed primers targeting orf1 and optrA demonstrated that the region containing optrA and cfr was part of a plasmid which was designated pE35048-oc (Figure 1). The plasmid was 41,816 bp in size, contained 42 open reading frames (ORFs), and had a G + C content of 35%.

S1-PFGE analysis of genomic DNA extracted from E. faecium E35048 showed four plasmids, ranging in size from ∼10 to ∼250 kb (data not shown). Both optrA and cfr probes hybridized with a plasmid of ∼45 kb, in agreement with sequencing data.

The characteristics of the plasmid ORFs and of their products are detailed in Table 1. In particular, pE35048-oc carried (i) a repS gene (orf6, corresponding to orf6 of pRE25), encoding a theta mechanism replication protein responsible for the plasmid replication; (ii) a putative origin of replication downstream of orf6; and (iii) a region containing the putative minimal conjugative unit of pRE25, consisting of 15 ORFs (orf28 to orf14, corresponding to orf24 to orf39 of pRE25) and the origin of transfer (oriT) found upstream of orf28 (Schwarz et al., 2001). BLASTN analysis showed that the oriT nucleotide sequence was shorter in pE35048-oc (only 15 bp vs. 38 bp in pRE25). Compared to pRE25, pE35048-oc lacked (i) the region spanning from orf41 to orf5 (two IS1216 elements probably involved in the rearrangement occurred during plasmid evolution); (ii) orf10, i.e., the chloramphenicol resistance cat gene; and (iii) orf11, another replication gene encoding a rolling-circle replication protein. In addition, compared to pRE25, pE35048-oc carried the optrA and cfr genes and their respective genetic environments.

Table 1.

Amino acid sequence identities/similarities of putative proteins encoded by the pE35048-oc (GenBank accession no. MF580438).

| BLASTP

analysisa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Start (bp) | Stop (bp) | Size (amino Acid) | Predicted function | Most significant database match | Accession no. | % Amino acid identity (% aminacid similarity) |

| orfl | 1833 | 1 | 610 | DNA Topoisomerase III | Type 1 topoisomerase (plasmid) [Enterococcus faecium] | YP_976069.1 | 100 (100) |

| orfl | 3,818 | 1,932 | 628 | Group II intron | Group II intron reverse transcriptase/maturase [Lactobacillales] | WP_010718345.1 | 100 (100) |

| bΔorf3 | 4,917 | 4,555 | 120 | DNA Topoisomerase III | Topoisomerase [Bacilli] | WP_000108744.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf4 | 5,534 | 4,917 | 205 | Resolvase | Resolvase (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP_003864109.1 | 99 (100) |

| orf5 | 5,718 | 5,548 | 56 | Hypothetical protein pRE25p07 (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP_783891.1 | 98 (100) | |

| orf6 | 7,557 | 6,067 | 496 | Replication protein | Replication protein (plasmid) [E. faecium] | NP_044463.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf7 | 8,213 | 7,941 | 90 | Transcriptional regulator | CopS (plasmid) [Streptococcus pyogenes] | YP_232751.1 | 100 (100) |

| Δorf8 | 8,901 | 8,446 | 151 | Responsible for lincomycin resistance | Lincosamide nucleotidyltransferase (plasmid) [E. faecium] | ARQ19308.1 | 99 (100) |

| orf9 | 9,772 | 8,873 | 299 | Transposase | Transposase [Streptococcus suis] | AGO02197.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf10 | 10,443 | 9,769 | 224 | Transposase | IS3 family transposase [E. faecalis] | WP_013330754.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf11 | 11,867 | 10,809 | 352 | 23S ribosomal RNA methyltransferase | Cfr family 23S ribosomal RNA methyltransferase [Staphylococcus aureus] | WP_001835153.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf12 | 13,177 | 12,278 | 299 | Transposase | Transposase [S. suis] | AGO02197.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf13 | 13,848 | 13,174 | 224 | Transposase | IS3 family transposase [E. faecalis] | WP_013330754.1 | 100 (100) |

| Δorf8 | 13,921 | 14,061 | 47 | Responsible for lincomycin resistance | Lincomycin resistance protein [synthetic construct] | AGT57825.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf14 | 15,391 | 14,531 | 289 | Hypothetical protein [S. suis] | WP_079268203.1 | 96 (98) | |

| orf15 | 15,822 | 15, 451 | 123 | Hypothetical protein [Enterococcus casseliflavus] | WP_032495652.1 | 99 (99) | |

| orf16 | 16,546 | 15,809 | 245 | Hypothetical protein [E. faecalis] | WP_012858057.1 | 100 (100) | |

| orf17 | 17,768 | 16,836 | 310 | Hypothetical protein [Enterococcus sp. HMSC063D12] | WP_070544061.1 | 100 (100) | |

| orf18 | 18,693 | 17,770 | 307 | Membrane protein insertase | Hypothetical protein [Enterococcus sp. HMSC063D12] | WP_070544063.1 | 99 (99) |

| orf19 | 20,366 | 18,711 | 551 | Type IV secretory pathway, VirD4 component, TraG/TraD family ATPase | Hypothetical protein [Enterococcus] | WP_002325630.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf20 | 20,790 | 20,359 | 143 | Ypsilon (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP_003864141.1 | 100 (100) | |

| orf21 | 21,346 | 20,795 | 183 | Hypothetical protein [E. faecium] | WP_02 9485693.1 | 99 (99) | |

| orf22 | 22,468 | 21,359 | 369 | Amidase | Putative lytic transglycosylase (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP_003864139.1 | 99 (99) |

| orf23 | 23,842 | 22,490 | 450 | Conjugal transfer protein TraF [E. faecium] | WP_085837474.1 | 98 (99) | |

| orf24 | 25,817 | 23,856 | 653 | Type IV secretory pathway, VirB4 component | TrsE (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP_003864137.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf25 | 26,457 | 25,828 | 209 | Hypothetical protein [Enterococcus] | WP_002325627.1 | 99 (100) | |

| orf26 | 26,857 | 26,474 | 127 | AM21 (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP 003305365.1 | 100 (100) | |

| orf27 | 27,208 | 26,876 | 110 | T4SS_CagC | Hypothetical protein pRE25p25 (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP_783909.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf28 | 29,217 | 27,232 | 661 | Nickase | Molybdopterin-guanine dinucleotide biosynthesis protein MobA [E. faecalis] | WP_025186512.1 | 99 (100) |

| orf29 | 29,509 | 29,808 | 99 | Hypothetical protein pRE25p23 (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP_783907.1 | 100 (100) | |

| orf30 | 29,811 | 30,068 | 85 | Hypothetical protein [Enterococcus] | WP_021109234.1 | 100 (100) | |

| orf31 | 30,927 | 30,430 | 165 | Molecular chaperone DnaJ | Molecular chaperone DnaJ [Enterococcus] | WP_025481726.1 | 97 (98) |

| orf32 | 31,353 | 30,946 | 135 | Hypothetical protein pRE25p20 (plasmid) [E. faecalis] | YP_783904.1 | 98 (99) | |

| Δorf33 | 32,376 | 31,705 | 223 | Zeta-toxin | Toxin zeta [E. faecium] | WP_002300569.1 | 97 (98) |

| orf34 | 33,173 | 32,412 | 253 | DNA replication protein DnaC | AAA family ATPase [Proteiniborus ethanoligenes] | WP_091728780.1 | 94 (98) |

| orf35 | 34,750 | 33,170 | 526 | ISEfa15 transposase | Transposase [P. ethanoligenes] | WP_091728892.1 | 70 (84) |

| orf36 | 36,973 | 35,006 | 655 | ABC-F type ribosomal protection protein | ABC-F type ribosomal protection protein OptrA [E. faecalis] | WP_078122475.1 | 97 (98) |

| orf37 | 38,100 | 37,078 | 340 | ISEfa15 transposase (partial) | Transposase [Clostridium formicaceticum] | WP_070963420.1 | 64 (80) |

| Δorf33 | 38,423 | 39,199 | 75 | Zeta-toxin | Zeta toxin [E. faecium] | WP_080440976.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf38 | 38,697 | 38,425 | 90 | Epsilon-antitoxin | Antidote of epsilon-zeta post-segregational killing system (plasmid) [S. pyogenes] | YP_232758.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf39 | 38,929 | 38,714 | 71 | Omega-repressor | Transcriptional repressor (plasmid) [S. pyogenes] | YP_232757.1 | 99 (100) |

| orf40 | 39,917 | 39,021 | 298 | ParA putative ATPase | Chromosome partitioning protein ParA [S. suis] | WP_0023 87620.1 | 100 (100) |

| orf41 | 40,445 | 40,314 | 43 | Hypothetical protein (plasmid) [Pediococcus acidilactici] | WP_002321978.1 | 100 (100) | |

| orf42 | 41,187 | 40,450 | 245 | 23S rRNA (adenine(2058)-N(6)) methyltransferase | 23S rRNA (adenine(2058)-N(6))-methyltransferase Erm(B) [S. suis] | WP_024418925.1 | 99 (100) |

aFor each ORF, only the most significant identity detected is listed. bΔ represents a truncated ORF.

The optrA context (5,850 bp) consisted of the optrAE35048 gene followed by a novel insertion sequence of the IS21 family, named ISEfa15. Consistently with other members of this family (Berger and Haas, 2001), ISEfa15 included two CDS encoding a transposase and a helper protein, and was bounded by 11-bp imperfect inverted repeats (IRL 5′-TGTTTATGATA-3′ and IRR 5′-TGTATTTGTCA-3′). A truncated copy of ISEfa15, named ISEfa15∗, was present also upstream of optrA gene. This optrA context was flanked by 5-bp target site duplications (5′-CTAAT-3′) suggesting its mobilization as a composite transposon, named Tn6628 (Figure 1). This transposon was previously shown to form circular intermediate (3,350 bp) including optrA and the truncated copy of ISEfa15 (Brenciani et al., 2016b).

The proposed role of IS1216 in the dissemination of optrA among different types of enterococcal plasmids (He et al., 2016) is likely to be true also for other transposase genes. The optrA context was located downstream of the erm(B) gene (orf15 of pRE25) and was integrated into orf33 (orf19 of pRE25, which encodes the ζ toxin protein of the ω-ε-ζ toxin/antitoxin system). This integration inactivates ζ toxin encoded by orf33, a condition that could prevent the correct partitioning of pE35048-oc and lead to the appearance of plasmid-free segregants (Magnuson, 2007).

The cfr context (6,098 bp) was located between orf7 and orf14 (orf39 and orf40 of pRE25) and consisted of the cfr gene flanked by two ISEnfa5 elements, inserted in turn into the lnu(E) gene. The same genetic context of cfr [including the direct repeats and the lnu(E) gene] has been reported in China in a plasmid from a Streptococcus suis isolate from an apparently healthy pig (Wang et al., 2013) and in Italy in an MRSA isolated from a patient with cystic fibrosis (Antonelli et al., 2016), with cfr being untransferable in both instances. Very recently, the cfr gene, flanked by only one ISEnfa5, inserted upstream, has been described in a chromosomal fragment shared by three pig isolates of Staphylococcus sciuri (Fan et al., 2017).

PCR assays, using primer pairs targeting regions flanking the optrA and the cfr contexts (Figure 1), and sequencing experiments confirmed that both genes could be excised leaving one of the two flanking genes (ISEfa15 or ISEnfa5, respectively) at the excision sites.

Transferability of the optrA and cfr Genes and Curing of E. faecium E35048 From pE35048-oc

Repeated attempts of conjugation and transformation assays failed to demonstrate any optrA or cfr transfer from E. faecium E35048 to enterococcal recipients. The partial deletion of oriT and the lack of the rolling-circle replication protein might be responsible for the non-conjugative behavior of pE35048-oc compared to pRE25 (Schwarz et al., 2001).

An optrA- and cfr-negative isogenic strain of E. faecium E35048 was obtained after three passages on BHA at 42°C. It was subjected to WGS. Compared to the wild type, it disclosed complete loss of pE35048-oc.

pE35048-oc vs. Other Plasmids Sharing Co-carriage of optrA and cfr

Since this study was started, co-location of optrA and cfr has been reported in a few additional plasmids, some from pig isolates of S. sciuri (Li et al., 2016; Fan et al., 2017) and one, pEF12-0805, from a human isolate of E. faecium (Lazaris et al., 2017). Comparison of pE35048-oc with the S. sciuri plasmids revealed completely unrelated backbones and optrA and cfr contexts. On the other hand, pE35048-oc was related with pEF12-0805 (accession no. KY579372.1) although with significant differences (Figure 1). In particular:

(i) pE35048-oc and pEF12-0805 share a pRE25-related backbone (Schwarz et al., 2001), but pEF12-0805 is much larger (72,924 bp vs. 41,816 bp) due to the presence of a larger amount of pRE25-related regions, including the pRE25 region spanning from orf51 to orf5 (∼12,5 kb) and a rearranged region of pRE25 containing antibiotic resistance genes aphA, aadE, and lnu(B) (∼13 kb). (ii) A ∼4-kb remnant of the ermA-carrying transposon Tn554 (Murphy et al., 1985) is found only in pEF12-0805. (iii) The optrA contexts of the two plasmids are completely different, only the optrA gene of pE35048-oc being part of a composite transposon. The absence of insertion sequences makes it unlikely that the optrA gene of pEF12-0805 is excisable. Moreover, whereas in pE35048-oc the optrA context is found downstream of erm(B), the optrA gene of pEF12-0805 is associated with the ermA-carrying Tn554 remnant. (iv) Interestingly, the cfr contexts of the two plasmids are the same, including some plasmid backbone flanking regions on either side (Figure 1), suggesting that the two plasmids might be derived from a pRE25-related common ancestor that had initially acquired the mobile cfr element. (v) Repeated transfer assays were unsuccessful with both plasmids. Finally, (vi) whereas we obtained a pE35048-oc-cured derivative of our E. faecium isolate, curing assays were unsuccessful with E. faecium strain F120805 (Lazaris et al., 2017).

The E. faecium hosts of the two plasmids belonged to different sequence types and were isolated from different sources. Strain E35048 was recovered in 2015 in Italy from a blood culture, belonged to ST117, exhibited no mutational mechanisms of oxazolidinone resistance, and was vancomycin susceptible. Strain F120805, recovered in 2013 in Ireland from feces and reported to have a linezolid MIC of 8 μg/ml, belonged to ST80, exhibited also mutational mechanisms of oxazolidinone resistance (involving both 23S rRNA and ribosomal protein L3), and was vancomycin resistant (vanA genotype). Although belonging to different sequence types, ST80 and ST117 were part of the same clonal group, ST78.

Conclusion

Distinctive findings of the optrA- and cfr-carrying plasmid pE35048-oc are its relation to the well-known enterococcal plasmid pRE25, shared with plasmid pEF12-0805 (Lazaris et al., 2017); a unique optrA context, that has never been described before; and the fact that both the optrA and cfr contexts are capable of excising to form minicircles. This, in addition to the belonging of E. faecium E35048 to ST117, a globally disseminated clone recovered in many European health institutions (Hegstad et al., 2014; Tedim et al., 2017), might favor the spread of optrA and cfr in the hospital setting. Under this respect, the in vitro non-transferability of pE35048-oc is someway reassuring, although transfer in vivo cannot be ruled out. Moreover, at the hospital level, it cannot be excluded that co-carriage of optrA and cfr by the same plasmid ends up turning into co-spread, as already highlighted with pheromone-responsiveness plasmids (Francia and Clewell, 2002), and also in consideration of the very recent finding that, in enterococci, non-conjugative plasmids can be mobilized by co-resident, conjugative plasmids (Di Sante et al., 2017). Co-spread would be a cause for special concern, considering that both optrA and cfr encode resistance, through diverse mechanisms, to different antibiotics, including last resort agents such as oxazolidinones.

Author Contributions

AB, PV, and EG designed the study and wrote the paper. FB, OC, and GR have contributed to critical reading of the manuscript. GM, AA, MD, VD, SF, MM, CV, and SF did the laboratory work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

- Antonelli A., D’Andrea M. M., Galano A., Borchi B., Brenciani A., Vaggelli G., et al. (2016). Linezolid-resistant cfr-positive MRSA, Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 2349–2351. 10.1093/jac/dkw108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias C. A., Murray B. E. (2012). The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10 266–278. 10.1038/nrmicro2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton B. M., Harding G. P., Zuccarelli A. J. (1995). A general method for detecting and sizing large plasmids. Anal. Biochem. 226 235–240. 10.1006/abio.1995.1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger B., Haas D. (2001). Transposase and cointegrase: specialized transposition proteins of the bacterial insertion sequence IS21 and related elements. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58 403–419. 10.1007/PL00000866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenciani A., Bacciaglia A., Vecchi M., Vitali L. A., Varaldo P. E., Giovanetti E. (2007). Genetic elements carrying erm(B) in Streptococcus pyogenes and association with tet(M) tetracycline resistance gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 1209–1216. 10.1128/AAC.01484-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenciani A., Morroni G., Pollini S., Tiberi E., Mingoia M., Varaldo P. E., et al. (2016a). Characterization of novel conjugative multiresistance plasmids carrying cfr from linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolates from Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 307–313. 10.1093/jac/dkv341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenciani A., Morroni G., Vincenzi C., Manso E., Mingoia M., Giovanetti E., et al. (2016b). Detection in Italy of two clinical Enterococcus faecium isolates carrying both the oxazolidinone and phenicol resistance gene optrA and a silent multiresistance gene cfr. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 1118–1119. 10.1093/jac/dkv438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco L. M., Bernal J. F., Zankari E., Léon M., Hendriksen R. S., Perez-Gutierrez E., et al. (2017). Detection of linezolid resistance due to the optrA gene in Enterococcus faecalis from poultry meat from the American continent (Colombia). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 678–683. 10.1093/jac/dkw490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande L. M., Ashcraft D. S., Kahn H. P., Pankey G., Jones R. N., Farrell D. J., et al. (2015). Detection of a new cfr-like gene, cfr(B), in Enterococcus faecium isolates recovered from human specimens in the United States as part of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 6256–6261. 10.1128/AAC.01473-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sante L., Morroni G., Brenciani A., Vignaroli C., Antonelli A., D’Andrea M. M., et al. (2017). pHTβ-promoted mobilization of non-conjugative resistance plasmids from Enterococcus faecium to Enterococcus faecalis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 2447–2453. 10.1093/jac/dkx197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan R., Lia D., Feßler A. T., Wu C., Schwarz S., Wang Y. (2017). Distribution of optrA and cfr in florfenicol-resistant Staphylococcus sciuri of pig origin. Vet. Microbiol. 210 43–48. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francia M. V., Clewell D. B. (2002). Transfer origins in the conjugative Enterococcus faecalis plasmids pAD1 and pAM373: identification of the pAD1 nic site, a specific relaxase and a possible TraG-like protein. Mol. Microbiol. 45 375–395. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A. R., Elghaieb H., León-Sampedro R., Abbassi M. S., Novais C., Coque T. M., et al. (2017). Detection of optrA in the African continent (Tunisia) within a mosaic Enterococcus faecalis plasmid from urban wastewaters. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 3245–3251. 10.1093/jac/dkx321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A. R., Tedim A. P., Francia M. V., Jensen L. B., Novais C., Peixe L., et al. (2016). Multilevel population genetic analysis of vanA and vanB Enterococcus faecium causing nosocomial outbreaks in 27 countries (1986-2012). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 3351–3366. 10.1093/jac/dkw312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T., Shen Y., Schwarz S., Cai J., Lv Y., Li J., et al. (2016). Genetic environment of the transferable oxazolidinone/phenicol resistance gene optrA in Enterococcus faecalis isolates of human and animal origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 1466–1473. 10.1093/jac/dkw016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegstad K., Longva J. Å., Hide R., Aasnæs B., Lunde T. M., Simonsen G. S. (2014). Cluster of linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecium ST117 in Norwegian hospitals. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 46 712–715. 10.3109/00365548.2014.923107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrenberg C., Schwarz S., Jacobsen L., Hansen L. H., Vester B. (2005). A new mechanism for chloramphenicol, florfenicol and clindamycin resistance: methylation of 23S ribosomal RNA at A2503. Mol. Microbiol. 57 1064–1073. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04754.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaris A., Coleman D. C., Kearns A. M., Pichon B., Kinnevey P. M., Earls M. R., et al. (2017). Novel multiresistance cfr plasmids in linezolid-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE) from a hospital outbreak: co-location of cfr and optrA in VRE. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 3252–3257. 10.1093/jac/dkx292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Wang Y., Schwarz S., Cai J., Fan R., Li J., et al. (2016). Co-location of the oxazolidinone resistance genes optrA and cfr on a multiresistance plasmid from Staphylococcus sciuri. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 1474–1478. 10.1093/jac/dkw040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson R. D. (2007). Hypothetical functions of toxin-antitoxin systems. J. Bacteriol. 189 6089–6092. 10.1128/JB.00958-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes R. E., Hogan P. A., Jones R. N., Sader H. S., Flamm R. K. (2016). Surveillance for linezolid resistance via the Zyvox® annual appraisal of potency and spectrum (ZAAPS) programme (2014): evolving resistance mechanisms with stable susceptibility rates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 1860–1865. 10.1093/jac/dkw052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morroni G., Brenciani A., Simoni S., Vignaroli C., Mingoia M., Giovanetti E. (2017). Commentary: nationwide surveillance of novel oxazolidinone resistance gene optrA in Enterococcus isolates in China from 2004 to 2014. Front. Microbiol. 8:1631. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munita J. M., Bayer A. S., Arias C. A. (2015). Evolving resistance among gram-positive pathogens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 61 48–57. 10.1093/cid/civ523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Huwyler L., de Freire Bastos Mdo C. (1985). Transposon Tn554: complete nucleotide sequence and isolation of transposition-defective and antibiotic-sensitive mutants. EMBO J. 4 3357–3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R., Gallagher J. C. (2015). Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia pharmacotherapy. Ann. Pharmacother. 49 69–85. 10.1177/1060028014556879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Mendes R. E., Streit J. M., Hogan P. A., Flamm R. K. (2017a). Five-year summary of in vitro activity and resistance mechanisms of linezolid against clinically important gram-positive cocci in the United States from the LEADER surveillance program (2011 to 2015). Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 61:e00609-17. 10.1128/AAC.00609-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Mendes R. E., Streit J. M., Hogan P. A., Flamm R. K. (2017b). ZAAPS Program results for 2015: an activity and spectrum analysis of linezolid using clinical isolates from medical centres in 32 countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 3093–3099. 10.1093/jac/dkx251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosvoll T. C. S., Pedersen T., Sletvold H., Johnsen P. J., Sollid J. E., Simonsen G. S., et al. (2010). PCR-based plasmid typing in Enterococcus faecium strains reveals widely distributed pRE25-, pRUM-, pIP501- and pHTβ-related replicons associated with glycopeptide resistance and stabilizing toxin-antitoxin systems. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58 254–268. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00633.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz F. V., Perreten V., Teuber M. (2001). Sequence of the 50-kb conjugative multiresistance plasmid pRE25 from Enterococcus faecalis RE25. Plasmid 46 170–177. 10.1006/plas.2001.1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey L. K. R., Edwards T. A., O’Neill A. J. (2016). ABC-F proteins mediate antibiotic resistance through ribosomal protection. mBio 7:e01975. 10.1128/mBio.01975-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K. J., Barbachyn M. R. (2011). The oxazolidinones: past, present, and future. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1241 48–70. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06330.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siguier P., Perochon J., Lestrade L., Mahillon J., Chandler M. (2006). ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 D32–D36. 10.1093/nar/gkj014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedim A. P., Lanza V. F., Manrique M., Pareja E., Ruiz-Garbajosa P., Cantón R., et al. (2017). Complete genome sequences of isolates of Enterococcus faecium sequence type 117, a globally disseminated multidrug-resistant clone. Genome Announc. 5:e01553-16. 10.1128/genomeA.01553-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Li D., Song L., Liu Y., He T., Liu H., et al. (2013). First report of the multiresistance gene cfr in Streptococcus suis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 4061–4063. 10.1128/AAC.00713-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Lv Y., Cai J., Schwarz S., Cui L., Hu Z., et al. (2015). A novel gene, optrA, that confers transferable resistance to oxazolidinones and phenicols and its presence in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium of human and animal origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70 2182–2190. 10.1093/jac/dkv116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner G., Klare I., Witte W. (1997). Arrangement of the vanA gene cluster in enterococci of different ecological origin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 155 55–61. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12685.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. N. (2016). The ABC of ribosome-related antibiotic resistance. mBio 7:e00598-16. 10.1128/mBio.00598-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]