Abstract

Study Objective:

To compare the clinical and oncologic outcomes of Robotic radical hysterectomy (RRH) vs Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (TLRH) in patients with cervical carcinoma.

Design:

Long term follow-up in a prospective study between March 2010 to March 2016.

Setting:

Oncological referral center, department of gynecology and obstetrics of Alessandro Manzoni Hospital, department of gynecology, University of San Gerardo Monza, Milan.

Patients:

52 patients with cervical carcinoma, matched by age, body mass index, tumor size, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, comorbidity, previous neoadjuvant chemotherapy, histology type, and tumor grade to obtain homogeneous samples.

Interventions:

Patients with FIGO stage IA2 or IB1 with a tumor size less than or equal to 2 cm underwent RR type B. RR-Type C1 was performed in stage IB1, with a tumor size larger than 2 cm, or in patients previously treated with NACT (IB2). In all cases Pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed for the treatment of cervical cancer.

Measurements and main results:

Surgical time was similar for both the 2 groups. RRH was associated with significantly less (EBL) estimated blood loss (P=0,000). Median number pelvic lymph nodes was similar, but a major number of nodes was observed in RRH group (35.58 vs 24.23; P=0,050). The overall median length of follow-up was 59 months (range: 9-92) and 30 months (range: 90-6) for RRH and TLRH group respectively. Overall survival rate (OSR) was 100% for RRH group and 83.4% for LTRH group. The DFS (disease free survival rate) was of 97% and 89% in RRH and LTRH group respectively. No significant difference was reported in HS (hospital stay).

Conclusions:

RRH is safe and feasible and is associated with an improved intraoperative results and clinical oncological outcomes. The present study showed that robotic surgery, in comparison to laparoscopic approach, was associated with better perioperative outcomes because of a decrease of EBL, and similar operative time, HS and complication rate, without neglecting the long-term optimal oncologic outcomes. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: robotic radical hysterectomy, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, cervical cancer, complications, progression-free survival, overall survival, long term follow-up

Introduction

Incorporation of total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (TLRH) offered the advantages of minimal invasive surgery without compromising the surgical and oncologic outcomes (1). The concept of laparoscopic management of gynecological malignancies has converted from a perceived near impossibility to a fully recognized option for many patients over the last decade. Unfortunately, a laparoscopic approach has not been recognized or accepted to treat endometrial and/or cervical cancers by the majority of gynecological oncologists. However, robotic-assisted laparoscopy (RAL) holds appeal and the current prototype is well suited for oncologic surgery.

Recently, RAL, which is FDA approved, has become an option in the definitive surgical management of early stage endometrial and cervical cancers (2). The Da Vinci robotic surgical system (da Vinci, Surgical System; Intuitive Surgical Inc, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) provides surgeons with a greater range of instrument movement, enhanced dexterity, and improved 3-dimensional visualization. These advantages enable surgeons to overcome some of the limitations of traditional laparoscopy, especially in case of complex procedures such as radical hysterectomy (3-4). This technologic surgical modality offers numerous advantages over conventional laparoscopy, well described in literature. Since 2007, it was reported a significant increase in the appropriateness of the RAL for several gynecologic oncology procedures: radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer (89.1% compared with 60.2% in 2007) (5).

In this prospective analysis, the feasibility and clinical and oncologic outcomes of RRH (Robotic radical hysterectomy) type B and C1 compared with TLRH, for cervical cancer were evaluated, with a median long follow-up evaluation.

Materials and methods

From March 2010 to March 2016, 34 consecutive patients underwent RRH and 18 patients underwent TLRH type B and C1 with systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy (PLH), according to Querleu-Morrow classification (6), at Alessandro Manzoni Hospital, which is an RAL referral center in Italy. RRH group was compared TLRH group matched by age, body mass index, tumor size, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, comorbidity, previous neoadjuvant chemotherapy, histology type, and tumor grade to obtain homogeneous samples. Inclusion criteria included the following: tumor size of 3 cm or less, most common histology types, and absence of medical conditions that would be a contraindication. When the Da V inci system was available, patients were operated by robotic assistance. If it was not available, the conventional laparoscopy was chosen.

The same surgeon (A.P.), who has an extensive experience in laparoscopic and abdominal gynecologic surgery, performed all the robotic procedures. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

The operative, clinic-pathological and survival data were abstracted from the patients’ medical records including: patient demographics, histology, clinical stage, surgical margins (parametrium, and paracolpum) lymph nodes retrieved, positive nodes present, perioperative data, intraoperative results, and postoperative complications, type of adjuvant therapy if necessary and time and sites of recurrence. Status of surgical margins, length of hospital stay (HS), time to resumption of normal bladder function, intraoperative and postoperative complications were analyzed.

Operating time was defined from the beginning of skin incision to completion of skin closure. Lymph node status, potential extra-pelvic disease, local extension of disease, tumor size, parametrium, and paracolpium were determined by MRI (magnetic resonance imaging scan). Previous abdominal surgery was not considered a contraindication.

Patients with histologically diagnosis of cervical cancer received the following evaluations: medical history collection, physical examination, vaginalpelvic examination, complete blood analysis, and chest x-ray and pelvic MRI scans. Cystoscopy and/ or proctoscopy was performed in case of suspicious involvement of the bladder or of the rectum, respectively. Positron emission tomography and computed tomography scan was selectively performed for suspicious nodal involvement or distant metastases. Endometrial or cervical specimens were obtained before surgery. All women received a detailed counseling session. The estimated blood loss (EBL) was calculated by the difference in the total amounts of suctioned and irrigation fluids.

Patients with cervical cancer FIGO stage IB2, underwent radical hysterectomy after completing 3 courses of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) with paclitaxel, epirubicine, and cisplatin regimen in case of squamous histology. Paclitaxel, ifosphamide, and cisplatin were indicated in women with adenocarcinoma histology. Adjuvant treatment was administered based on the presence of risk factors for recurrence in the final pathology findings.

Patients with FIGO stage IA2 or IB1 with a tumor size less than or equal to 2 cm underwent RR type B. RR-Type C1 was performed in stage IB1, with a tumor size larger than 2 cm, or in patients previously treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (IB2). Adjuvant treatment was based on the presence of risk factors for recurrence in the final pathology findings.

Using postoperative pathological results and risk classification, high-risk patients received postoperative chemo radiotherapy and intermediate-risk patients received radiotherapy. Complications were defined as those requiring return to the operating room or medical attention after discharge from the hospital. Complications were classified as intraoperative and early (≤7 days after surgery) or late with Clavien-Dindo classification. All patients have antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazoline 2 g and metronidazole 500 mg intravenously) and pre-operative low molecular weight enoxaparin in a single dose (40 mg/24 h subcutaneously). In addition, intraoperative lower extremity sequential compression devices for venous thrombosis prophylaxis are used. All procedures were performed under general endotracheal anesthesia.

RRH was performed by using the da Vinci S system. The da Vinci System (da Vinci, Surgical System; Intuitive Surgical Inc) has been used since 2008. Surgical procedures are currently performed by using 3 instruments: the Maryland fenestrated bipolar forceps, the monopolar curved scissors, and the Prograsp forceps. The patient was positioned supine with both arms tucked comfortably, and her legs placed in Allen stirrups, abducted and with hip extension to accommodate the second assistant surgeon. A Foley catheter was placed to empty the bladder and control urine output, and a uterine manipulator was introduced through the cervix. Induction of pneumoperitoneum was established to 20 mmHg.

All 4 robotic arms were used. One assistant trocar was placed in the left upper quadrant, and the initial access was obtained at the umbilicus by open Hasson technique. RRH was performed as described by Magrina et al. (7). Systematic PLH comprising the resection of the external and common iliac nodes, medial and lateral suprainguinal nodes, obturator and sacral nodes. All staging was performed in accordance with the 2009 FIGO guidelines.

We routinely removed the catheter on day 2 after surgical procedure; then, after the first trial of voiding of the patient, we measured residual urine volumes and if it was >100 ml, we performed self-catheterization.

In selected cases, patients were discharged with a Foley catheter in place then removed in the office one week after surgery. Visual analog scale (VAS) was administered at the first day after surgery.

Data were collected during recruitment and HS, as well as at each follow-up visit. Kolmogorov-Smirnov with Lilliefors correction was used to evaluate the normal distribution of the data of the collected variables. Whereas frequencies and proportions were used as summary statistics for categorical variables, mean and SD (standard deviation) for continuous variables.

By using Fisher exact test, the categorical variables were compared; for continuous variables, either a 2-tailed t test, when the normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions were met. Progression-free, disease-specific survival was defined as the time from surgery to the date of first recurrence.

Overall, disease-specific survival was defined as the time from surgery to the date of death as recorded in the social security death index. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival curves, and the differences in survival were analyzed using the logrank test. In all statistical tests, a confidence interval of 95% and P <0.05 were considered as significant differences. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS version 20.0 program.

Results

After excluding 5 patients in the RRH group and 7 in the TLRH due to incomplete clinical data, 34 RRH patients were compared with 18 TLRH during the study period. In all cases PLH was performed for the treatment of cervical cancer in our institution, between March 2009 and March 2014.

Baseline patients’ characteristics are summarized in table 1. 11 of 54 (21%) patients received NACT regimens, 6 (18 %) in RRH (3 cases of TIP and TEP, respectively) and 5 (27%) in TLRH group (3 cases of TIP; 2 cases of TEP).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| RRH Mean ± SD Median (range) (n=34) (%) | TLRH Mean ± SD Median (range) (n=18)(%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 46,88 (±9,46) | 48,2 (±13,12) | 0,242 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27,91 (±5,75) | 23,93 (±3,92) | 0,293 |

| Pregnancy | 2 (2-6) | 2 (1-3) | |

| Spontaneous delivery | 1 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) | |

| Menopause | 10 (29) | 7 (30) | 0,545 |

| Previous surgery | 11 (32) | 6 (33) | 1 |

| Asa score >-3 | 7 (22) | 4 (22) | 1 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 6 (18) | 4 (22) | 1 |

7 patients (21%) in RRH group and 5 (28%) of TLRH group, underwent type-C RH. Type-B RH was performed in the remaining cases, 79% and 72% in RRH and TLRH group, respectively. FIGO stage and oncologic data are reported in table 2.

Table 2.

Oncologic data

| Robotic n=34 (%) | Laparoscopy n=18(%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIGO stage% | |||

| IA1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| IA2 | 2 (6) | 1 (5) | 1 |

| IB1 | 25 (73) | 12 (68) | 0.743 |

| IB2 | 6 (18) | 4 (22) | 0.721 |

| IIA1 | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 1 |

| IIA2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Grading | |||

| G1-2 | 6 (18) | 3 (17) | 1 |

| G2 | 19 (56) | 9 (50) | 0.773 |

| G3 | 9 (27) | 6 (33) | 0.741 |

| Histology | |||

| Squamous | 25 (73) | 10 (55) | 0.223 |

| adenocarcinoma | 9 (27) | 8 (44) | 0.223 |

| Type of radical hysterectomy | |||

| C | 7 (21) | 5 (28) | 0.730 |

| B | 27 (79) | 13 (72) | 0.730 |

Median operative time was similar in both the groups (P=0.362), however less operative time was observed in RRH group (227.64±SD 51.32 min vs 242.87±90.03 min) (table 3).

Table 3.

Intra-operative data, post-operative outcomes

| RRH Mean ± SD Median (range) (n=34)(%) | TLRH Mean ± SD Median (range) (n=18) (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of the hospital stay (days) | 2,58 (±1) | 3.27 (±1,79) | 0,148 |

| Median pelvic lymph nodes | 35,58 (±12,03) | 24,23 (±6,54) | 0,050 |

| Docking | 230 (120-355) | NA | / |

| Operative time | 227,64 (±51,32) | 242,87 (±90,03) | 0,362 |

| Blood loss ml | 67,88 (±118,39) | 203,33 (±218,65) | 0,000 |

| Discharge with self-catheterization | 0 | 3 | 0.036 |

| Discharge with Foley catheter in place | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| fever | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Late complications | 4** | 5 | 0.241 |

| Vaginal dehiscence | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lymphocele | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Ureteral fistula | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Reintervention | 1 | 3 | 0.112 |

| Readmission | 1 | 4* | 0.043 |

Operative time and lymph node yields were acceptable in RRH group. Number of lymph nodes were similar in both the groups, 35.58 (SD±12.03) in RRH group vs 24.23 (SD±6.54) in LTRH group, however a major number was observed in RRH group. Incidence of positive lymph node status was 3% vs 33% between the LTRH and RRH groups, respectively.

Pathology confirmed the adequacy of the surgical specimen: both parametria and length of vaginal margin resulted adequate without no difference between the two groups. Right parametria was 2.2 mm (range: 2-3.4) vs 2.3 mm (range: 1.8-3.5), while left parametria was 2.1 mm (2-3.2) vs 2.4 mm (1.9-3.2), for RRH and LTRH group, respectively. No positive parametrial or vaginal margins were reported.

Median tumor size was similar in both groups, 18 mm (12-30) vs 16 mm (15-32) in RRH and LTRH group. Median vaginal margin was 16.8 mm (12-25) vs 15.5 mm (13-21), for RRH and LTRH group. EBL was significant less in RRH group (67.88±SD 118.39 ml vs 203.33±SD 218.65 ml; P=0.000).

One patient in RRH group, required conversion to laparotomy for massive bleeding from iliac artery and any patient required an intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion, in both the groups.

One case for each group, required re-intervention for vaginal cuff dehiscence at 60 and 34 days after the surgery. 1 cases of early re-intervention was reported in the TLRH group, due to an ureteral fistula.

A second case of complication in the TLRH group was an ureterovaginal fistula, diagnosed 1 month later by urography; the patient underwent placement of a ureteral stent 1 week later, that was removed after 3 months with no sequela. There was no difference for lymphocele between in both the groups, which resulted asymptomatic in all cases and spontaneously regressed.

The median time to resumption of bladder function, was of 2 days (range: 1-3) in the RRH group and of 3 days (range: 1-30) in the TLRH group.

In RRH all patients were voiding spontaneously without any difficulty, while in TLRH group 3 patients were discharged with self-catheterization, resolved 7 days later, in 2 cases, with a statistically significant difference (p=0.036), and 1 patients with catheter in place removed after 30 days after the surgery.

Postoperative fever was reported in two cases of the TLRH group and in any patients of the RRH group. VAS for pain was decreased by three points on the first postoperative day (range of decrease: 2-6) in 30 patients in the RRH and in 5 patients in the LTRH (P= 0.001) (figure 1). Ketoprofen was used to control pain. In TLRH was necessary infusion of morphine.

Figure 1.

Example of schedules of VAS marked by the patients

Regarding the oncologic outcomes, 3 patients died for a recurrent disease in the LTRH group with squamous histology. 1 patient (stage IB1) had recurrence on the vaginal cuff, after 8 months and received chemo-radiation therapy, with death 15 months later. The second case (stage IB1) had a recurrence 4 months after surgery, and death, six months later. In the third recurrence (stage IB2) the patient was free of disease for 84 months. Lung metastasis and death after 92 months from the last surgery was reported. Readmissions were statically major in TLRH group.

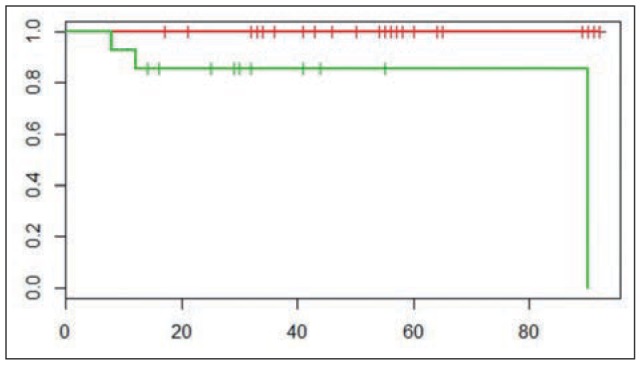

The overall median length of follow-up was 59 months (range 9-92 months) for the RRH group and 30 months (90-6 months) for TLRH group. Overall survival rate was 100% for RRH and 83.4% and for LTRH (figure 1), and The DFS was of 97% and 89% in RRH and LTRH group respectively without no statistical difference. No deaths due to disease were observed in the RRH group. 4 patients in LTRH and 5 patients in RRH group with a previous neoadjuvant treatment, received a consolidation regimen of chemotherapy of 2 cycles after surgery. Using postoperative pathological results and risk classification, patients in a high-risk group (4 LRH and 6 RRH) received post-operative radiotherapy and/or chemo-radiation, while patients in an intermediate-risk group received radiotherapy (1 case in each group).

Figure 2.

KaplaneMeier (Mantel-Cox test) plot of overall survival rate in the RRH and TLRH groups (log-rank test p=0. 00184; Chisq= 9.7 on 1 degrees of freedom). Red line: RRh; Green line: TLRH

Discussion

Although short-term outcomes of RRH for cervical cancer are widely reported, data equating the longterm outcomes of cervical cancer patients treated with TLRH compared with RRH are scant. Previous studies found that RRH was feasible and effective in reducing the blood loss. However, few studies compared surgical and oncological outcomes between RRH and LTRH (8,9). Despite the experience with this procedure is ever growing, the oncologic outcomes for patients undergoing RRH are still uncertain. After the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) clearance for gynecologic surgery in 2005,17 the first robot-assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (RRH) for cervical cancer was reported by Bilal M. Sert (10,11).

Furthermore as to long-term outcomes, only three studies (12-14) mentioned the DFS; The removal of the parametria and the upper vagina defines a radical hysterectomy (13,15), but in several studies these data are lacking. In the two included studies (13,15), additional pathological parameters (the parametrial size and vaginal cuff length) were investigated to ensure that the surgical specimen removed was similar between the two surgical approaches, as in our analysis. Furthermore, despite the appropriate follow-up of our series, the small number of patients in LTRH group is an important drawback. After a median follow-up of 30 months (90-6), in TLRH group, 3 (17%) patients had a recurrence and subsequently died of disease. The OS rate was significantly different between the two groups, but it must be underlined that two of the three deaths happened before of 10 months of follow-up. This data associated with the minor number of the patients in TLRH group, could bring a bias in calculation of the OSR. However, mean time recurrence was 35.3 months (SD±38.7) in TLRH group. No port site metastases were recorded.

In previous studies, a large number of surgeons were involved in the procedures from each institution with no information on individual learning curves regarding robot surgery which limits interpretation of the data.

Improved articulation of the robotic arms may have potentially reduced the technical skill acquisition time. Good ergonomics might reduce surgeon fatigue in more long oncological surgical procedures. These advantages permit more precise and accurate performance in complex radical gynecological surgery in addition to the known advantages. These complex procedures with RAL could be accomplished in a reasonable operative time with a minimal morbidity. The robotic device has the ability to transform hand’s movements into precise micro-movements of the jointed-wrist instrument, due to stability of the hands movements, making gesture intuitive that enables deep area location. Mandatory laparoscopic experience before robotic surgery is a controversial requirement.

Magrina et al (16) found that surgeon experience with LRH reduces RRH operating time. In our study, the single surgeon was technically proficient in TLRH. However, except for EBL, which was lower in RRH group, operating time, perioperative surgical outcomes including, EBL, complication rates, and transfusion rates were similar between the RRH and LRH groups. LRTH experience might ameliorate perioperative surgical outcomes and decrease surgery-associated complications during the initial experience with robotic surgery. During the last decade, minimally invasive surgery has been a fast-growing field in gynecologic malignancies. With regard to shorter operating time, reduced blood loss, more precise operative technique as demonstrated by number of retrieved pathological specimens, and faster acquisition time for competency compared with LRH, robotic surgery may be preferable over LRH and open surgery. Higher cost of robotic surgery than conventional laparoscopy is a major weak point of widespread use RAL, but in oncologic procedures the robotic cost are much less then benign condition as well demonstrated (17). However, surgical robots should be smaller and less expensive in the future.

Furthermore, surgeons must be taking into account the best choose for the patient, focusing the attention on the postoperative outcome (VAS, cosmetic outcomes, urinary retention etc.) and major benefits linked to the surgical procedure linked to RAL and not taking into account only intraoperative technical results.

Furthermore in our study, results of pelvic lymph nodes yielded, operative time, HS, late complications also if resulted not statically significant between the two groups, are better in RRH group.

Risk of laparoscopic port-site metastases is not high in gynecologic malignancy, not detected in our study, and its incidence has not been well defined (18, 19). However, due to the small number of patients, it is difficult to draw any conclusions.

RAL allows complex oncological procedures, such as radical hysterectomy, which requires delicate and precise dissection of the pelvic area (cardinal ligament, ureter, pelvic nodes and vessels), allowing good visualization of the pelvic plexus nerves, thereby allowing resection without nerve injury, maintaining oncological radicality to be completed by a single surgeon with a novice assistant and alleviates the need for an expert assistant, which is the ideal tool for performing complex oncological procedures.

RAL provides patients the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, including low short- and long-term complication risk and represents a logical advance in the evolution of endometrial cancer treatment.

However, the limitations of RAL as the limited experience with this recently developed technology, underline the importance of conducting clinic research in this area of gynecologic oncology.

The strength of this case series consists of a single surgeon experience with incorporation of radical hysterectomy with good long-term oncologic outcome. The present study showed that robotic surgery, in comparison to laparoscopic approach, was associated with better perioperative outcomes because of a decrease of EBL, and similar operative time and HS, and complication rate without neglecting the long-term oncologic outcomes. In agreement with other authors, RAL was safe in terms of intraoperative and postoperative complications (20,21). We think as previously there was skepticism toward laparoscopy, which was demonstrated to be preferable to open surgery in patients requiring radical hysterectomy(20-25), also RAL should be confirmed, in near future as the gold standard surgical procedure for cervical cancer.

Conclusions

Unfortunately, a laparoscopic approach has not been recognized or accepted to treat endometrial and/ or cervical cancers by the majority of gynecological oncologists. However RAL holds appeal and the current prototype is well-suited for oncologic radical surgery for cervical cancer.

Recently, RAL, which is FDA approved, has become an option in the definitive surgical management of early stage endometrial and cervical cancers. In conclusion, the data reported support its safety and feasibility with an available median long-term follow-up evaluation and an overall survival rate of 100%. At our center, gynecologic oncological staging and other complex procedures have been safely and successfully completed using RAL.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Puntambekar SP, Palep RJ, Puntambekar SS, et al. Laparoscopic total radical hysterectomy by the Pune technique: our experience of 248 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:682–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damiani GR, Turoli D, Cormio G, et al. Robotic approach using simple and radical hysterectomy for endometrial cancer with long-term follow-up evaluation. Int J Med Robot. 2016;12(1):109–13. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Neugut AI, et al. Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive and abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoogendam JP, Verheijen RH, Wegner I, et al. Oncological outcome and long-term complications in robot-assisted radical surgery for early stage cervical cancer: an observational cohort study. BJOG. 2014;121:1538–45. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conrad LB, Ramirez PT, Burke W, et al. Role of Minimally Invasive Surgery in Gynecologic Oncology: An Updated Survey of Members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(6):1121–7. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Querleu D, Morrow CP. Classification of radical hysterectomy. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:297–303. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magrina JF, Kho R, Magtibay PM. Robotic radical hysterectomy: technical aspects. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko EM, Muto MG, Berkowitz RS, et al. Robotic versus open radical hysterectomy: a comparative study at a single institution. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:425–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruijdenberg CB, van den Einden LC, Hendriks JC, et al. Robot-assisted versus total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy in early cervical cancer, a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:334–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.12.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sert BM, Abeler VM. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy(Piver type III) with pelvic node dissectionecase report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006;27(5):531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf5/k05404.pdf.Administration. FDA. Gynecologic laparoscope and accessories 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CH, Chiu LH, Chang CW, et al. Comparing robotic surgery with conventional laparoscopy and laparotomy for cervical cancer management. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1105–11. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tinelli R, Malzoni M, Cosentino F, et al. Robotics versus laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy in patients with early cervical cancer: a multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2622–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estape R, Lambrou N, Diaz R, et al. A case matched analysis of robotic radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy compared with laparoscopy and laparotomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:333–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soliman PT, Frumovitz M, Sun CC, et al. Radical hysterectomy: a comparison of surgical approaches after adoption of robotic surgery in gynaecological oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:357–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magrina JF, Kho RM, Weaver AL, et al. Robotic radical hysterectomy: comparison with laparoscopy and laparotomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tapper AM, Hannola M, Zeitlin R, et al. A systematic review and cost analysis of robot-assisted hysterectomy in malignant and benign conditions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;177:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Wolf JK, Levenback C. Laparoscopic portsite metastases in patients with gynecological malignancy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:1070–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.14604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagarsheth NP, Rahaman J, Cohen CJ, et al. The incidence of port-site metastases in gynaecologic cancers. JSLS. 2004;8:133–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shazly SA, Murad MH, Dowdy SC, et al. Robotic radical hysterectomy in early stage cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:457–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magrina JF, Kho RM, Weaver AL, et al. Robotic radical hysterectomy: comparison with laparoscopy and laparotomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boggess JF, Gehrig PA, Cantrell L, et al. A case-control study of robot-assisted type III radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection compared with open radical hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:357. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nezhat FR, Datta MS, Liu C, et al. Robotic radical hysterectomy versus total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with pelviclymphadenectomy for treatment of early cervical cancer. JSLS. 2008;12:227–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persson J, Reynisson P, Borgfeldt C, et al. Robot assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy with short and long term morbidity data. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:185–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YT, Kim SW, Hyung WJ, et al. Robotic radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical carcinoma: a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:312–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]