Abstract

Background:

In the last decades, after some initial concern, laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy (LSG) is gaining popularity also for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer (AGC). The aim of this study is to compare a single surgeon initial experience on LSG and open subtotal gastrectomy in terms of surgical safety and radicality, postoperative recovery and midterm oncological outcomes.

Methods:

a case control study was conducted matching the first 13 LSG for AGC with 13 open procedures performed by the same surgeon. Operative and pathological data, postoperative parameters and midterm oncological outcomes were analyzed.

Results:

There was no significant difference in mortality (0%) and morbidity, while the laparoscopic approach allowed lower analgesic consumption and faster bowel movement recovery. Operation time was significantly higher in LSG patients (301.5 vs 232 min, p: 0.023), with an evident learning curve effect. Both groups had a high rate of adequate lymph node harvest, but the number was significantly higher in LSG group (p: 0.033). No significant difference in survival was registered. Multivariate analysis identified age at diagnosis, diffuse-type tumor, pN and LODDS as independent predictors of worse prognosis.

Conclusions:

LSG can be safely performed for the treatment of AGC, allowing faster postoperative recovery. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: gastric cancer, laparoscopic gastrectomy, survival, lymphadenectomy

Introduction

In spite of its declining incidence in the last decades, gastric cancer still represents the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the world (1-3), owing to its poor prognosis (4, 5).

Even though recent progress in adjuvant therapies has led to improvement in the overall survival rate (6, 7) the only curative therapeutic option for gastric cancer is adequate surgical resection

The aim of surgical treatment is to remove the tumour along with the regional lymph nodes, by means of a total or subtotal gastrectomy, depending on tumour site, with an adequate lymphadenectomy (8). In recent years, a minimally invasive approach to gastric cancer has been widely developed mainly in Eastern countries (9). Laparoscopic (laparoscopically-assisted) gastrectomy (LG), since its first description by Kitano (10), has been increasingly adopted, becoming the intervention of choice in many Centres for the treatment of Early Gastric Cancer (ECG). Indeed, many studies have assessed an advantage of LG over open gastrectomy (OG) for EGC in terms of postoperative outcome parameters, with an equivalent rate of recurrences (11-14), while data on long-term oncological outcomes, still lacking, are being validated by ongoing phase III clinical trials (15). Despite an initial concern, due to technical and oncological issues, the laparoscopic approach is rapidly gaining popularity also in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer (AGC), but its use as gold standard procedure still needs thorough long-term evaluation (16). As to other types of procedures (17, 18), the potential benefits of the laparoscopic approach to gastric cancer should never be offset by reduced oncological radicality or surgical safety.

The aim of this study is to compare a single surgeon experience on LSG and OSG in terms of surgical safety and radicality, postoperative outcomes and midterm oncological outcomes.

Methods

Study Protocol

Starting from 2011 we prospectively enrolled a series of 13 consecutive patients submitted to laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy (LSG) for AGC at our Institution. All the interventions were performed by a single surgeon (F.M.), experienced in oncological surgery, upper GI laparoscopic surgery and intracorporeal suturing (bariatric surgery), but at his first experience on LSG. Proximal localization of the tumor (requiring total gastrectomy), metastatic disease, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, previous major abdominal surgery or gastric surgery, ASA status >3 and urgency setting were set as exclusion criteria. A series of 13 consecutive patients, previously submitted to open subtotal gastrectomy (OSG) for AGC by the same surgeon, was used as the control group.

Preoperative workup included an endoscopy with biopsy and an abdominal and thoracic CT scan for all the patients. In case of suspected metastatic disease a positron emission tomography (PET) or magnetic resonance imaging (RMI) was added. All patients received IV antibiotic prophylaxis with 3 g of ampicillin/sulbactam and subcutaneous administration of low-weight heparin before surgery (dalteparin sodium 35 UI/kg). Symeticone (400 mg) was administered the day before surgery only to patients in the LSG group.

Surgical procedure

Laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy

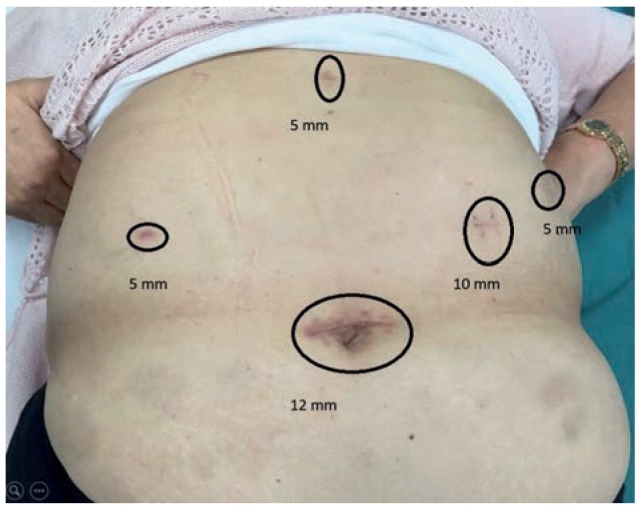

Under general anaesthesia, 12 mmHg pneumoperitoneum was created with a Veress needle. Five trocars were inserted in the upper abdomen (Fig. 1). The first step consisted in lateral to medial colon-epiploic dissection of the greater omentum and of the gastrocolic ligament beyond the gastroepiploic vessels, in order to remove the homonymous lymph node stations (station 4sb). The right gastroepiploic vessels were sectioned too, in order to allow infra-pyloric lymph node stations removal (station 6); nodes along superior mesenteric vein were also removed (station 14 v). Next step was the section of the hepatoduodenal ligament, followed by ligation and section of the right gastric vessels. The duodenum was then divided using a 60 mm endoscopic linear stapler, completing the excision of the right gastro-epiploic (station 4 d) and supra and subpyloric lymph node station (stations 5 and 6). Lymphadenectomy was extended to the common hepatic artery station (station 8) and to the hepatoduodenal ligament (stations 12a). The stomach was mobilized and overturned upward after the ligation of the left gastric artery and vein with lymph node dissection around the celiac trunk and the left gastric artery (stations 7 and 9). The splenic artery lymphadenectomy was then performed (station 11p). Esophago-gastric dissection was then completed and lymphadenectomy was extended up to right crus (stations 3, 1). Gastric resection was performed at a distance of at least 7 cm from the tumour using a 60mm endoscopic linear stapler. An antecolic gastrojejunal side to side anastomosis was performed on the major gastric curvature, using a 45 mm linear stapler. The enterotomy was then closed with a double layer of manual intracorporeal suture using polygalactin 2-0 stitches. Jejunojejunal mechanical side-to-side anastomosis between alimentary and biliary limb was finally performed, at 60 cm from the ligament of Treitz. The specimen was extracted through an enlargement of umbilical trocar incision. A single drain was left in place.

Figure 1.

Trocar position

Open gastrectomy

The same steps as for laparoscopic approach were carried out through a midline xifo-umbilical laparotomy. Differently from LSG an antecolic, partial oral gastrojejunal anastomosis was performed manually, in double continuous layer. Jejunojejunal anastomosis was performed manually in double layer.

Postoperative management

The nasogastric tube was normally removed after the first flatus. Early mobilization of the patient is always attempted. Intravenous ketoprofen (100 mg/ vial) was used for postoperative pain control. Hospital discharge was scheduled after full recovery from postoperative ileus, feeding on normal diet and after a good level of self-sufficiency had been achieved; however, patients were not discharged before postoperative day 8, which, traditionally, we consider as being the “safety interval” for anastomosis healing (19).

Data Collection

Patients’ demographics, operative parameters (time, blood loss), postoperative data, pathological data (tumor location; histotype according to the Lauren Classification (20); tumor grade; tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) (7th Edition) (21, 22); number of lymph nodes examined; number of lymph nodes positive; lymph nodes ratio) and oncological data (recurrence, overall survival) were prospectively collected. Analgesic consumption (vials) was adopted as a postoperative pain parameter. The Clavien-Dindo classification (23) was adopted for surgical complications, and only complications scored > II were matched. The Lymph Node Ratio (LNR) was calculated as a percent value by dividing the total number of lymph nodes harboring metastases by the total number of examined nodes (24, 25).

LODDS were calculated by the empirical logistic formula: log of the ([pLN + 0.5] / [tLN – pLN + 0.5]) where: pLN = positive lymph nodes and tLN = total harvested lymph nodes. In order to avoid an infinite number 0.5 was added to both the numerator and the denominator (26).

Data of the control group were obtained from the Parma Tumor Registry and the patient clinical charts.

Statistical analysis

Because of the reduced number of cases included in the study, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney rank test for two independent variables were used for the comparison of continuous variables, whereas association of dichotomous variables was assessed through the Fishers’ exact test. Univariate survival analysis was performed through Kaplan-Meier statistics: LSG and OSG were compared through the Log-rank (MantelCox) test, with calculation of respective Hazard Ratio (HR) for LSG vs. OSG, and respective survival curves were elaborated. Statistical analysis was performed by using software package SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY). A difference with p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

As shown in table 1, cases and controls were similar for demographics, biometric parameters and ASA status.

Table 1.

Patients demographic and tumor characteristics

| Approach | VL (N = 13) | Open (N = 13) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | |||

| Median (range) | 74 (52 to 88) | 75 (69 to 82) | 0.424 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8, 61.5% | 8, 61.5% | 1.000 |

| Female | 5, 38.5% | 5, 38.5% | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Median, range | 25.2 (21.9 to 34.5) |

26.7 (21.9 to 30.2) |

0.745 |

| <25.0 kg/m1 | 5, 38.5% | 6, 46.1% | 0.920 |

| 25.0 - 29.9 kg/m2 | 7, 5.4% | 6, 46.1% | |

| 30.0 kg/m2 or more | 1, 7.7% | 1, 7.7% | |

| ASA | |||

| ASA2 | 2, 15.4% | 0, - | 0.480 |

| ASA3 | 11, 84.6% | 13, 100% | |

| Histologic type | 0.251 | ||

| Intestinal | 4, 30.8% | 8, 61.5% | |

| Diffuse | 5, 38.5% | 2, 15.4% | |

| Mixed | 4, 30.8% | 3, 23.1% | |

| Grading | 0.013 | ||

| G1 | 0, - | 0, - | |

| G2 | 1, 7.7% | 8, 61.5% | |

| G3 | 12, 92.3% | 5, 38.5% | |

| Staging (AJCC) | 0.229 | ||

| IA | 0, - | 0, - | |

| IB | 0, - | 0, - | |

| IIA | 3, 23.1% | 3, 23.1% | |

| IIB | 0, - | 2, 15.4% | |

| IIIA | 2, 15.4% | 1, 7.7% | |

| IIIB | 6, 46.2% | 2, 15.4% | |

| IIIC | 2, 15.4% | 5, 38.5% | |

In patients submitted to LSG tumor grade was higher (p: 0.013) while stage did not significantly differ among the groups, as well as nodal involvement (LNR, LODDS). Intestinal type tumor was more frequent in OSG group (61% vs 31%).

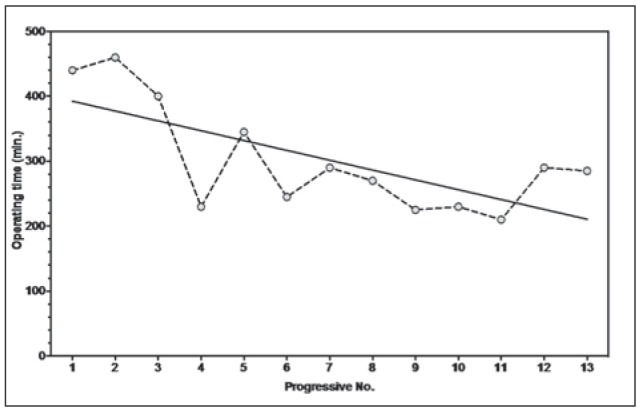

Operation time was significantly higher in LSG patients (301.5 ± 84.2 vs 232.0 ± 58.9 p: 0.023), even though such a difference seems to decrease with a “learning curve” effect (Fig. 2). No conversion to open occurred.

Figure 2.

Operative times (laparoscopic gastrectomy)

Blood loss was similar in cases and controls (table 2). Harvested lymph nodes were higher in patients undergone LSG (26.3 ± 8.1vs18.5 ± 9.2; p: 0.033), and 92% of the LSG group and 77% of the OSG group had adequate lymphadenectomy (more than 15 nodes according to the AJCC and NCCN guidelines (8, 20)).

Table 2.

Outcomes

| Approach | VL (N = 13) | Open (N = 13) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operation time (minutes, range) | 285 (210 to 460) | 230 (155 to 360) | 0.023 |

| Post-Operative Complications (CD>2) | 0, - | 1, 7.7% | 1.000 |

| Blood Loss (ml, range) | 78 (22 to 190) | 89 (60 to 150) | 0.685 |

| Pain Vials (range) | 11.9 (9 to 18) | 15.3 (13 to 22) | 0.047 |

| Post-operative Ileum (days, range) | 3 (2 to 6) | 3 (3 to 12) | 0.042 |

| Time to oral feeding (days, range) | 4 (3 to 9) | 5 (4 to 8) | 0.205 |

| Hospital Stay (days, range) | 9 (6 to 28) | 10 (8 to 23) | 0.419 |

| Harvested Lymph nodes | |||

| Median (range) | 27 (10 to 36) | 16 (11 to 44) | 0.033 |

| < 15 | 1, 7.7% | 3, 23.1% | 0.593 |

| 15 or more | 12, 92.3% | 10, 76.9% | |

| Positive Lymph nodes | |||

| Median (range) | 10 (0 to 16) | 6 (0 to 21) | 0.551 |

| LN ratio | |||

| Median (range) | 38.2 (0 to 100) | 45.5 (0 to 73.3) | 0.954 |

| LODDS | |||

| Median (range) | -0.2021 | ||

| (-1.7559 to 1.3222) | -0.7255 | ||

| (-1.5185 to 0.4074) | 0.795 | ||

| Short term (<1 year) recurrence% | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

Values expressed as medians

We had no mortality in both groups. No major complication (Clavien Dindo >2) was registered in in LSG group, while 1 patient submitted to OSG was reoperated on postoperative day 7 due to acute bleeding. Postoperative course was better for LSG, with lower analgesic consumption (11.9 vs 15.3 p: 0.047) and faster bowel movement recovery (mean: 2.3 vs 3.89 p: 0.042), while time to oral feeding was not significantly different between the groups (table 2). Mean hospital stay was 10.7 days in LSG and 12.3 in OSG (p: 0.419).

Both LSG and OSG allowed for a free margin resection in all cases. No early recurrence (<12 months) was registered.

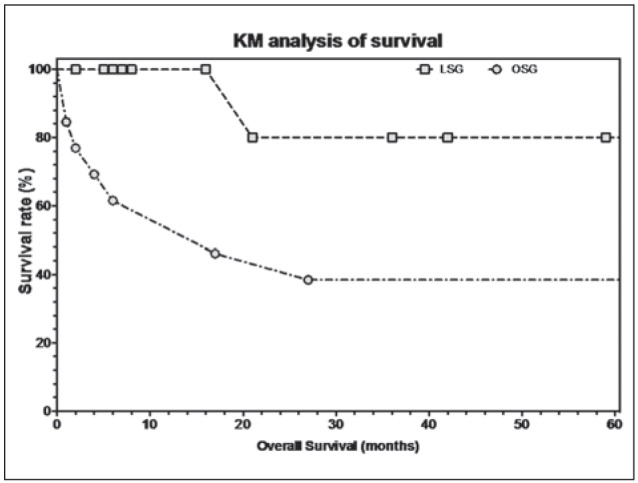

Overall survival (KM analysis) was higher for LSG (57.0 months 95%CI 41.2 to 72.8 vs. 51.2 months 95%CI 22.2, p = 0.022; HR 0.139, 95%CI 0.059 to 0.809) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Overall survival post operation (KM analysis)

Discussion

Over the last decades, laparoscopic surgery has gained increasing popularity in several fields of oncologic surgery, allowing a proven postoperative advantage without affecting oncological outcome. Unlike colonic cancer surgery, though, the laparoscopic approach to gastric cancer is still source of debate, being accepted, and not widely adopted, only for EGC (2729) or undiagnosed lesions (30).

Despite many studies assessed an advantage on clinical outcome for LSG (11-14), a recent meta-analysis (12) showed the absence of significant differences in postoperative outcome parameters in the few randomized studies included. In fact, LSG seems to allow shorter hospital stay and lower postoperative pain, while refeeding time can be biased by a variable number of unpredictable prolonged gastroparesis, which seems to be poorly influenced by the type of surgical approach or reconstruction. Differently from what Kim et al. stated (11), postoperative benefits seem not so evident as for colonic surgery, where the difference on abdominal invasiveness between the open and laparoscopic approach is probably higher (12). Moreover, some authors (31) perform a laparoscopically-assisted procedure, using a wide “service” laparotomy to perform the anastomosis: in a frequently not obese abdomen (as the case of gastric cancer patients), the difference in laparotomy length between LSG and OSG ends up as being often not relevant.

Moreover, many technical issues about LSG safety have been raised. In particular, given the supposed oncological superiority of D2 dissection in AGC treatment (32, 33), the initial concern about the feasibility of an adequate laparoscopic dissection D2 has limited the routinely use of LSG for gastric cancer in advanced stages (12). In fact, in western countries, D2 dissection is considered a recommended but not required procedure, even though there is uniform consensus that removal of an adequate number of lymph nodes (>15) is beneficial for staging purposes (8). A recent metaanalysis (34) based on non-randomized trials seems to suggest that D2 lymphadenectomy performed laparoscopically is as effective as an open procedure, even in AGC.

The anastomose technique represents another important technical issue for laparoscopic gastrectomy. A specific skill in intracorporeal suturing is required for LSG, whereas even major, and apparently nonsolved, technical problems are related to intracorporeal esophagojejunal anastomosis after laparoscopic total gastrectomy, where a gold standard technique has not yet been identified. In fact, due to the higher anastomosis-related complication rate, as reported by Lee (31), LTG is still under investigation.

In our series, LSG seems to confirm the postoperative outcome benefits reported by previous studies, even though a prolonged gastroparesis may delay the refeeding thus affecting the recovery of patients in both groups.

The number of harvested lymph nodes was significantly higher in LSG, and, in most of cases (92%), oncologically adequate, confirming that lymphadenectomy should not be considered a technical issue for a surgeon trained in laparoscopic and oncological surgery, even at his first experience on laparoscopic gastric resection for AGC. On the other hand, as reported in most series (14, 16), operative times were longer for LSG (301.5 ± 84.2 vs 232.0 ± 58.9 p:0.023), but did not entail any higher blood loss or complication rate. Some authors suggested a learning curve of 50 cases for LSG (35); as shown in graphic 1, considerable reduction of surgical times can be achieved after few procedures if the surgeon is experienced in intracorporeal suturing and anastomosis, as already demonstrated, for instance, in colonic surgery (36, 37).

Oncological outcomes cannot be clearly evaluated by our series, because of the few cases matched and the relatively short follow-up. However, LSG allowed adequate resection in terms of free margin and lymphadenectomy in all the patients; therefore, it can be assumed that survival difference depends only on cancer stage and biology, as per the prognostic factors of multivariate analysis (Age, tumour type, pN, LODDS). Moreover, former concerns on cell seeding in laparoscopic oncologic resection (38, 39) seem to be overtaken by the extremely low number of port site implant reported and by the absence of short-term recurrence in the major studies (13), as well as in our series.

Conclusions

Our study confirms that LSG for AGC can be safely performed by a surgeon experienced in oncological and laparoscopic surgery, allowing faster recovery of the patient. Future randomized trials should confirm the equivalence on surgical outcomes.

References

- 1.Dicken BJ, Bigam DL, Cass C, Mackey JR, Joy AA, Hamilton SM. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg. 2005 Jan;241(1):27–39. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000149300.28588.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guggenheim DE, Shah MA. Gastric cancer epidemiology and risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:230–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.23262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Dicken BJ, Bigam DL, Cass C, Mackey JR, Joy AA, Hamilton SM. Cancer statistics, 2014. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg CA Cancer J Clin. 2014 2005 Jan;64 241(1):9–29. 27–39. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000149300.28588.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer. 2001 Oct;37(Suppl 8):S4–66. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mita MT, Marchesi F, Cecchini S, Tartamella F, Riccò M, Abongwa HK, Roncoroni L. Prognostic assessment of gastric cancer: retrospective analysis of two decades. Acta Biomed. 2016 Sep 13;87(2):205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roukos DH. Current status and future perspectives in gastric cancer management. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000 Aug;26(4):243–55. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2010;2011:113–23. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Almhanna K, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Das P, Denlinger CS, Fanta P, Farjah F, Fuchs CS, Gerdes H, Gibson M, Glasgow RE, Hayman JA, Hochwald S, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Jaroszewski D, Johung KL, Keswani RN, Kleinberg LR, Korn WM, Leong S, Linn C, Lockhart AC, Ly QP, Mulcahy MF, Orringer MB, Perry KA, Poultsides GA, Scott WJ, Strong VE, Washington MK, Weksler B, Willett CG, Wright CD, Zelman D, McMillian N, Sundar H. Gastric Cancer, Version 3.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016 Oct;14(10):1286–312. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen L, Shan YS, Hu HM, Price TJ, Sirohi B, Yeh KH, et al. Management of gastric cancer in Asia: resource-stratified guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e535–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, et al. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopyassisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248(5):721–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185e62e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viñuela EF, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Coit DG, Strong VE. Laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and high-quality nonrandomized studies. Ann Surg. 2012 Mar;255(3):446–56. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824682f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Best LM, Mughal M, Gurusamy KS. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 31;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011389.pub2. CD011389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, et al. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241(2):232–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000151892.35922.f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, Hyung WJ, Kim W, Lee HJ, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial (phase III) to comparing laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with open distal gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma (KLASS 01) J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;84:123–30. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2013.84.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quan Y, Huang A, Ye M, Xu M, Zhuang B, Zhang P, Yu B, Min Z. Comparison of laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: an updated meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2016 Jul;19(3):939–50. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0516-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cecchini S, Azzoni C, Bottarelli L, Marchesi F, Rubichi F, Silini EM, Roncoroni L. Surgical treatment of multiple sporadic colorectal carcinoma. Acta Biomed. 2017 Apr 28;88(1):39–44. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i1.6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchesi F, Rapacchi C, Pattonieri V, Tartamella F, Mita MT, Cecchini S. Minimally invasive esophagectomy for caustic ingestion after 73 years and over 200 endoscopic dilations: is it just a matter of time? Acta Biomed. 2016 Sep 13;87(2):220–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchesi F, Rapacchi C, Cecchini S, Sarli L, Tartamella F, Roncoroni L. Late surgical complications of subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic caeco-rectal anastomosis for slow transit constipation A critical analysis. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berlth F, Bollschweiler E, Drebber U, Hoelscher AH, Moenig S. Pathohistological classification systems in gastric cancer: Diagnostic relevance and prognostic value. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5679–84. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual and the Future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchet A, Mocellin S, Ambrosi A, Morgagni P, Vittimberga G, Roviello F, Marrelli D, De Manzoni G, Minicozzi A, Coniglio A, Tiberio G, Pacelli F, Rosa F, Nitti D. Validation of the new AJCC TNM staging system for gastric cancer in a large cohort of patients (n = 2,155): focus on the T category. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011 Sep;37(9):779–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL. Makuuchi The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen S, Zhao BW, Li YF, Feng XY, Sun XW, Li W, et al. The prognostic value of harvested lymph nodes and the metastatic lymph node ratio for gastric cancer patients: results of a study of 1,101 patients. PloS One. 2012;7:e49424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun Z, Xu Y, Li de M, Wang ZN, Zhu GL, Huang BJ, et al. Log odds of positive lymph nodes: a novel prognostic indicator superior to the number-based and the ratio-based N category for gastric cancer patients with R0 resection. Cancer. 2010;116:2571–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Bian YH, Jin X, Cao H. Prognostic assessment of different metastatic lymph node staging methods for gastric cancer after D2 resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Mar 28;19(12):1975–83. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y. A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs. laparoscopyassisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery (St. Louis) 2002;131:S306–11. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.120115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayashi H, Ochiai T, Shimada H, Gunji Y. Prospective randomized study of open versus laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with extraperigastric lymph node dissection for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1172–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Han HS, Lee JH. A prospective randomized study comparing open vs. laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: early results. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:168–73. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8808-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cecchini S, Marchesi F, Caruana P, Tartamella F, Mita MT, Rubichi F, Roncoroni L. Cyst of the gastric wall arising from heterotopic pancreas: report of a case. Acta Biomed. 2016 Sep 13;87(2):215–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JH, Nam BH, Ryu KW, Ryu SY, Park YK, Kim S, Kim YW. Comparison of outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted and open total gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2015 Nov;102(12):1500–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards P, Blackshaw GR, Lewis WG, Barry JD, Allison MC, Jones DR. Prospective comparison of D1 vs modified D2 gastrectomy for carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(10):1888–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchesi F, Mita MT, Cecchini S, Ziccarelli A, Michieletti E, Del Rio P, Roncoroni L. Obstructive jaundice by lymph node recurrence of gastric cancer: can surgical derivation still play a role? Hepatogastroenterology. 2014 Nov-Dec;61(136):2443–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu C, Zhou S, Peng Z, Chen L. Quality of D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer: is laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy as effective as open distal gastrectomy? Surg Endosc. 2015 Jun;29(6):1537–44. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3838-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim MC. Learning curve of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with systemic lymphadenectomy for early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7508. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i47.7508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchesi F, Pinna F, Percalli L, Cecchini S, Riccó M, Costi R, Pattonieri V, Roncoroni L. Totally laparoscopic right colectomy: theoretical and practical advantages over the laparo-assisted approach. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013 May;23(5):418–24. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarli L, Rollo A, Cecchini S, Regina G, Sansebastiano G, Marchesi F, Veronesi L, Ferro M, Roncoroni L. Impact of obesity on laparoscopic-assisted left colectomy in different stages of the learning curve. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009 Apr;19(2):114–7. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31819f2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita S, Ohki S, Kase K, Yamauchi N, Chida S, Hayase S, Sakamoto W, Monma T, Takawa M, Ohtake T, Kono K, Takenoshita S. A Case of Port Site Recurrence after Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2016 Nov;43(12):1502–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mautone D, Dall’asta A, Monica M, Galli L, Capozzi VA, Marchesi F, Giordano G, Berretta R. Isolated port-site metastasis after surgical staging for low-risk endometrioid endometrial cancer: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016 Jul;12(1):281–4. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]