Key Points

Question

What structures of the circadian system are impaired in Parkinson disease, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy?

Findings

In a brain bank case-control study (12 healthy controls, 28 Parkinson disease, 11 multiple system atrophy, and 21 progressive supranuclear palsy), a semiquantitative histologic analysis showed disease-related neuropathological inclusions in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in Parkinson disease and progressive supranuclear palsy samples, without involvement of the pineal gland. Both structures were preserved in healthy control and multiple system atrophy samples.

Meaning

Direct histologic involvement of the suprachiasmatic nucleus may explain circadian dysfunction in Parkinson disease and progressive supranuclear palsy but not in multiple system atrophy, which might have important therapeutic implications.

Abstract

Importance

Circadian dysfunction may be associated with the symptoms and neurodegeneration in Parkinson disease (PD), multiple system atrophy (MSA), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), although the underlying neuroanatomical site of disruption and pathophysiological mechanisms are not fully understood.

Objective

To perform a neuropathological analysis of disease-specific inclusions in the key structures of the circadian system in patients with PD, MSA, and PSP.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This investigation was a brain bank case-control study assessing neuropathological inclusions in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus and pineal gland in healthy controls, PD (Lewy pathology), MSA (glial cytoplasmic inclusions), and PSP (tau inclusions). The study analyzed 12 healthy control, 28 PD, 11 MSA, and 21 PSP samples from consecutive brain donations (July 1, 2010, to June 30, 2016) to the Queen Square Brain Bank for Neurological Disorders and the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank, London, United Kingdom. Cases were excluded if neither SCN nor pineal tissue was available.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Disease-specific neuropathological changes were graded using a standard semiquantitative scoring system (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or very severe) and compared between groups.

Results

Because of limited tissue availability, the following total samples were examined in a semiquantitative histologic analysis: 5 SCNs and 7 pineal glands in the control group (6 male; median age at death, 83.8 years; interquartile range [IQR], 78.2-88.0 years), 13 SCNs and 17 pineal glands in the PD group (22 male; median age at death, 78.8 years; IQR, 75.5-83.8 years), 5 SCNs and 6 pineal glands in the MSA group (7 male; median age at death, 69.5 years; IQR, 61.6-77.7 years), and 5 SCNs and 19 pineal glands in the PSP group (13 male; median age at death, 74.3 years; IQR, 69.7-81.1 years). No neuropathological changes were found in either the SCN or pineal gland in healthy controls or MSA cases. Nine PD cases had Lewy pathology in the SCN, and only 2 PD cases had Lewy pathology in the pineal gland. All PSP cases showed inclusions in the SCN, but no PSP cases had pathology in the pineal gland.

Conclusions and Relevance

Disease-related neuropathological changes were found in the SCN but not in the pineal gland in PD and PSP, while both structures were preserved in MSA, reflecting different pathophysiological mechanisms that may have important therapeutic implications.

This brain bank case-control study analyzes disease-specific inclusions in the key structures of the circadian system in patients with Parkinson disease, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Introduction

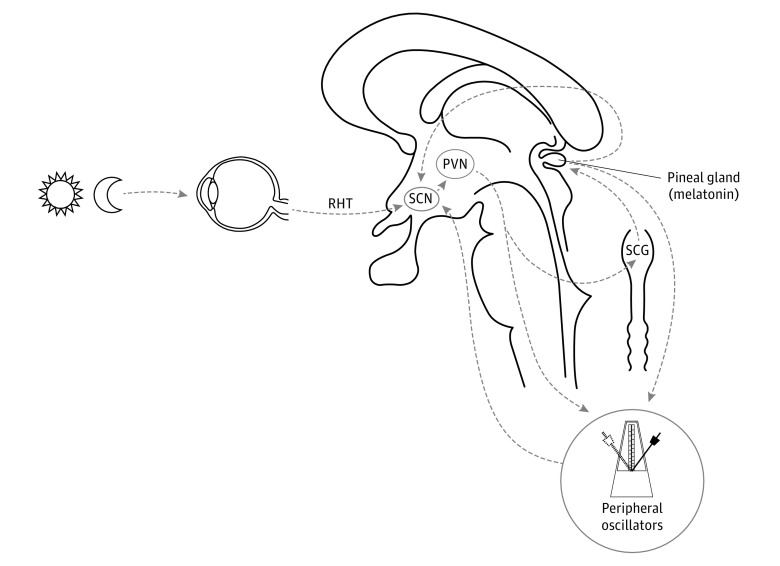

Almost all physiological functions in humans show circadian rhythms. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus acts as a central biological clock, and melatonin (produced by the pineal gland) is its main humoral efferent (Figure 1).2 Good synchronization of circadian rhythms is essential for optimal physical and mental health, and their disruption has been associated with neurodegeneration.3

Figure 1. Schematic Representation of the Circadian System in Humans.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus is the central biological clock, and its rhythmic activity is the result of the expression of clock genes. The SCN synchronizes all body functions in central and peripheral structures using neural and humoral (melatonin) signals. Melatonin secretion by the pineal gland is indirectly regulated by the SCN through a multisynaptic pathway via the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and superior cervical ganglion (SCG). The SCN receives time cues from circulating melatonin, the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT), and other peripheral oscillators. Modified with permission from the study by De Pablo-Fernández et al.1

Abnormalities in circadian activity, including melatonin secretion,4,5 are considered to be associated with some of the symptoms in patients with Parkinson disease (PD), such as disruption of the sleep-wake cycle, fluctuations of rest/motor activity, and neuroendocrine and autonomic functions.1 However, the neuroanatomical site of disruption remains unknown, and the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are not fully understood. Impairment of circadian function may also be associated with the clinical fluctuations of autonomic symptoms in multiple system atrophy (MSA)6,7,8,9 and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP),9,10,11 although direct evidence involving circadian function markers is lacking. The aim of this study was to provide a histopathological analysis of the key central structures of the circadian system in patients with PD, MSA, and PSP to investigate the underlying mechanisms of circadian dysfunction.

Methods

In this neuropathological case-control study, healthy controls and cases with a neuropathological diagnosis of PD, MSA, and PSP were selected from the archives of the Queen Square Brain Bank for Neurological Disorders (n = 62) and the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank (n = 10) in London, United Kingdom. The donation programs have research ethics committee approval, and written informed consent is obtained for all donations.

Postmortem formalin-fixed hypothalamic and pineal tissue was sampled, and 8-μm-thick sections were stained using standard protocols. Because the SCN cannot be confidently identified with routine staining, vasointestinal peptide (VIP) immunohistochemistry (1:80, ab8556; Abcam) was used to identify specific VIP-expressing neurons, which have a major role in circadian regulation.12 Cases were excluded if neither SCN nor pineal tissue was available. Because of limited tissue availability, the following total samples were examined in a semiquantitative histologic analysis: 5 SCNs and 7 pineal glands in the control group, 13 SCNs and 17 pineal glands in the PD group, 5 SCNs and 6 pineal glands in the MSA group, and 5 SCNs and 19 pineal glands in the PSP group (Table).

Table. Demographic Data and Histologic Comparisons by Study Groupa.

| Variable | Control (n = 12) | PD (n = 28) | MSA (n = 11)b | PSP (n = 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male-female sex | 6:6 | 22:6 (P = .07) | 7:4 (P = .52) | 13:8 (P = .51) |

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | NA | 67.1 (58.0-72.1) | 63.3 (57.0-68.3) | 66.5 (61.2-71.9) |

| Age at death, median (IQR), y | 83.8 (78.2-88.0) | 78.8 (75.5-83.8) (P = .10) |

69.5 (61.6-77.7) (P < .001) |

74.3 (69.7-81.1) (P < .001) |

| Disease duration, median (IQR), y | NA | 14.3 (7.2-20.0) | 5.4 (4.4-10.5) (P < .001)c |

7.2 (4.5-9.1) (P = .002)c |

| SCN | (n = 5) | (n = 13) | (n = 5) | (n = 5) |

| SCN pathology, No. (%) | 5 (100) Absent | 4 (31) Absent, 7 (54) mild, 2 (15) moderate (P = .01)d |

5 (100) Absent (P > .99)d |

2 (40) Mild, 3 (60) moderate (P = .003)d |

| Pineal Gland | (n = 7) | (n = 17) | (n = 6) | (n = 19) |

| Pineal pathology, No. (%) | 7 (100) Absent | 15 (88) Absent, 2 (12) mild (P = .35)d |

6 (100) Absent (P > .10)d |

19 (100) Absent (P > .99)d |

| Braak stage, No. (%) | NA | 3 (12) Braak stage 5, 22 (88) Braak stage 6 (P = .25)e |

NA | NA |

| Lewy body subtype, No. (%) | NA | 5 (22) Limbic, 18 (78) neocortical (P = .54)f |

NA | NA |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MSA, multiple system atrophy; NA, not applicable; PD, Parkinson disease; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus.

P values of Mann-Whitney test applied for comparisons with control group as reference unless stated otherwise.

Eight parkinsonian and 3 cerebellar.

The PD group as reference.

Percentage affected, disease group vs control group.

Percentage affected, Braak stage 5 vs Braak stage 6.

Percentage affected, limbic subtype vs neocortical subtype.

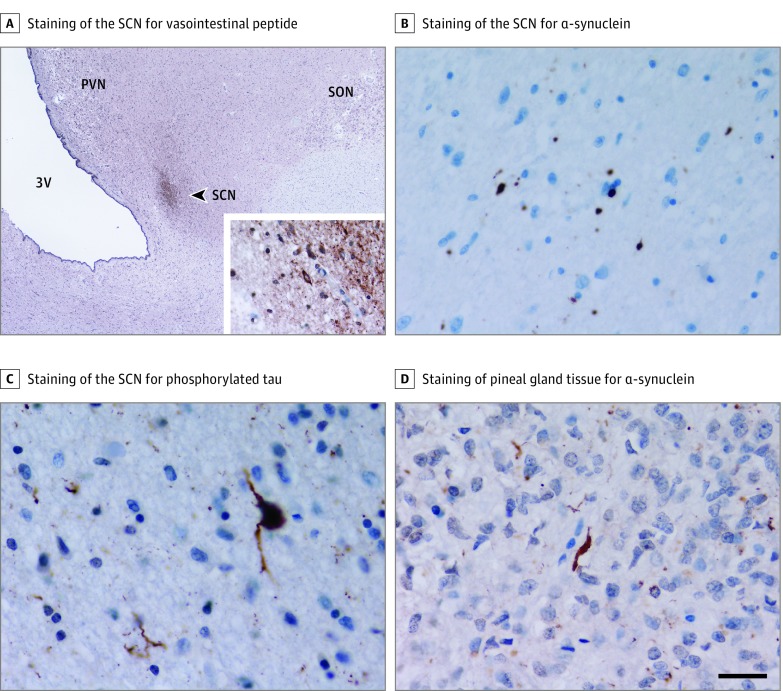

Immunohistochemistry for α-synuclein (1:50; Vector) and phosphorylated tau (1:600, AT8; Source BioScience) was performed. Lewy pathology (Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites) among PD cases, glial cytoplasmic inclusions among MSA cases, and PSP-related tau inclusions among PSP cases were assessed using a standard semiquantitative scoring system (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or very severe) in the SCN and pineal gland by an experienced neuropathologist (J.L.H.) (Figure 2). Braak stage (range, 0-6) and a Lewy pathology subtype (brainstem, limbic, or neocortical) was assigned for each PD case.

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical Staining of Representative Sections of the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN) and Pineal Gland.

A, Immunohistochemistry for vasointestinal peptide was used for identification of the SCN (A, arrowhead). The inset shows expression in neuronal cell bodies and processes. B and C, Immunohistochemical staining of the SCN for α-synuclein (B) showing Lewy pathology in a patient with Parkinson disease and for phosphorylated tau (C) showing tau pathology in a patient with progressive supranuclear palsy. D, Immunohistochemical staining of pineal gland tissue for α-synuclein showing Lewy pathology in a patient with Parkinson disease. Scale bar in D represents 520 μm in A and 25 μm in the inset of A and in B through D. PVN indicates paraventricular nucleus; SON, supraoptic nucleus; and 3V, third ventricle.

Kruskal-Wallis test was used for global comparisons, and Mann-Whitney test was used for pairwise comparisons. Results were not adjusted for multiple comparisons given the exploratory nature of the study, and results were considered statistically significant at 2-tailed P < .05. A software program (Stata, version 12; StataCorp LP) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

In total, 12 healthy controls, 28 PD, 11 MSA, and 21 PSP samples from consecutive brain donations (July 1, 2010, to June 30, 2016) were included in the study. Demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in the Table. The study groups did not differ by sex. The MSA and PSP patients were younger than the controls at the time of death and PD patients, and survival was shorter among the MSA and PSP patients compared with the PD patients (see the Table for statistical comparisons).

Among PD cases, Lewy pathology was demonstrated in 9 cases in the SCN with mild or moderate severity but in none of the controls. By contrast, mild α-synuclein deposition was found in only 2 pineal glands among PD cases (Table). Suprachiasmatic nucleus α-synuclein deposition was not associated with the extent and severity of Lewy pathology in the central nervous system analyzed by either Braak stage or Lewy pathology subtype.

Among PSP cases, the SCN showed PSP-related tau pathology of mild or moderate severity in all cases, but no tau pathology was found in pineal tissue. By contrast, MSA cases did not show any α-synuclein deposition in either the SCN or the pineal gland (Table).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first histologic analysis of the key regulatory structures of the circadian system in parkinsonian disorders. Our study demonstrated different patterns of neuropathological involvement of the circadian system in PD, MSA, and PSP. While circadian dysfunction is likely to be caused by direct involvement with disease-related protein inclusions affecting the central circadian pacemaker (SCN) in PD and PSP but not the pineal gland, neither of these structures was similarly involved in MSA. We found no association between SCN α-synuclein deposition and histologic progression in the central nervous system among patients with PD, although most of them were in an advanced stage of the disease, as expected in a brain bank series. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, we were unable to perform quantitative assessment of specific neuronal populations.

We previously demonstrated histologic involvement of the hypothalamus in patients with PD,13 but to date the SCN has not been assessed in PD or PSP. The pineal gland was unaffected by tau pathology in all PSP cases herein, and only mild α-synuclein deposition in the form of Lewy neurites was found in pineal tissue in 2 PD patients. To our knowledge, pineal gland tissue has been analyzed previously in only 3 patients with PD, and no Lewy bodies were found.14 However, Lewy pathology may have been underestimated because sensitive α-synuclein immunohistochemistry was not available at the time of that study.

In contrast with PD, the SCN and pineal gland seem to be spared from α-synuclein deposition in MSA. Previous studies6,7,8 have shown fluctuations of symptoms and body functions in patients with MSA, which could be explained in part by circadian abnormalities, although no studies to date have directly assessed markers of circadian function. Our results do not support involvement of the circadian system by α-synuclein inclusions in MSA, and it seems that circadian dysfunction in these patients may be secondary to degeneration of other systems, such as autonomic networks. Previous pathological studies have shown loss of vasopressin neurons in the SCN of patients with MSA,6 although vasopressin neurons are more involved in autonomic control, while circadian rhythm regulation is exerted by VIP-expressing neurons.12

In addition to its contribution to some of the symptoms in PD and PSP, circadian disruption has been linked to mechanisms involved in neurodegeneration (eg, regulation of oxidative stress, protein degradation, autophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA repair, and brain metabolism), and it has been proposed that circadian disruption could also influence the pathological process in neurodegenerative conditions.15 These findings are of importance because restoring a normal circadian activity by therapeutic interventions could potentially represent a novel target for symptomatic and disease-modifying interventions.3

Limitations

A clinical correlation of the histologic findings could have provided a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying circadian dysfunction. Clinical assessment of circadian function requires strict protocols and control of external factors. However, only routinely collected clinical data were available for our patients.

Conclusions

We have shown neuropathological changes in the SCN but not the pineal gland in the circadian system in patients with PD and PSP, while both structures are preserved in MSA. These findings may reflect different pathophysiological mechanisms of circadian dysfunction, which may have important therapeutic implications.

References

- 1.De Pablo-Fernández E, Breen DP, Bouloux PM, Barker RA, Foltynie T, Warner TT. Neuroendocrine abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(2):176-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saper CB. The central circadian timing system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23(5):747-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Videnovic A, Lazar AS, Barker RA, Overeem S. “The clocks that time us”: circadian rhythms in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(12):683-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Videnovic A, Noble C, Reid KJ, et al. Circadian melatonin rhythm and excessive daytime sleepiness in Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(4):463-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breen DP, Vuono R, Nawarathna U, et al. Sleep and circadian rhythm regulation in early Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(5):589-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benarroch EE, Schmeichel AM, Sandroni P, Low PA, Parisi JE. Differential involvement of hypothalamic vasopressin neurons in multiple system atrophy. Brain. 2006;129(pt 10):2688-2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozawa T, Soma Y, Yoshimura N, Fukuhara N, Tanaka M, Tsuji S. Reduced morning cortisol secretion in patients with multiple system atrophy. Clin Auton Res. 2001;11(4):271-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierangeli G, Provini F, Maltoni P, et al. Nocturnal body core temperature falls in Parkinson’s disease but not in multiple-system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2001;16(2):226-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt C, Berg D, Herting B, et al. Loss of nocturnal blood pressure fall in various extrapyramidal syndromes. Mov Disord. 2009;24(14):2136-2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh CM, Ruoff L, Varbel J, et al. Rest-activity rhythm disruption in progressive supranuclear palsy. Sleep Med. 2016;22:50-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki K, Miyamoto T, Miyamoto M, Hirata K. The core body temperature rhythm is altered in progressive supranuclear palsy. Clin Auton Res. 2009;19(1):65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JL, Lim AS, Chiang WY, et al. Suprachiasmatic neuron numbers and rest-activity circadian rhythms in older humans. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(2):317-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Pablo-Fernández E, Courtney R, Holton JL, Warner TT. Hypothalamic α-synuclein and its relation to weight loss and autonomic symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2017;32(2):296-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Critchley PH, Malcolm GP, Malcolm PN, Gibb WR, Arendt J, Parkes JD. Fatigue and melatonin in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54(1):91-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musiek ES, Holtzman DM. Mechanisms linking circadian clocks, sleep, and neurodegeneration. Science. 2016;354(6315):1004-1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]