Key Points

Question

What is the annual incremental cost to the Medicare Part D drug benefit program of using brand-name combination products instead of their generic components?

Findings

In this retrospective analysis of Medicare Part D expenditures, the difference between the amount Medicare reported spending in 2016 on 29 brand-name combination products and the estimated spending for their generic constituents for the same number of doses would have been $925 million, which includes $235 million if generic products had been prescribed at the same doses, $219 million using generic substitution at different doses, and $471 million from substitution of similar generic medications in the same therapeutic class.

Meaning

Generic substitution and therapeutic interchange may offer important opportunities to achieve substantial savings.

Abstract

Importance

Brand-name combination drugs can be more expensive than the sum of their components, especially when the constituent products are available as generic medications. The potential savings that could be achieved using generic components is not known.

Objective

To estimate the additional cost to Medicare of prescribing brand-name combination medications instead of generic constituents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective analysis for 2011 through 2016 using the Medicare data set of Part D beneficiaries prescribed any of the 1500 medications that accounted for the highest total spending in 2015. Brand-name combination drugs that had identical or therapeutically equivalent generic constituents were included.

Exposures

Brand-name, oral combination medications with constituents available either as generic drugs or therapeutically equivalent generic substitutes.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The estimated difference between the amount spent by Medicare on brand-name combination drugs and the estimated amount that would have been spent on substitutable generic components.

Results

Among the 1500 medications evaluated, 29 brand-name combination medications were separated into 3 mutually exclusive categories: constituents available as generic medications at identical doses (n = 20), generic constituents at different doses (n = 3), and therapeutically equivalent generic substitutes (n = 6). For the constituents available as generic medications at identical doses category, total spending by Medicare in 2016 on the brand-name combination products was $303 million and the estimated spending for the generic constituents would have been $68 million, which is an estimated difference of $235 million. For the generic constituents at different doses category, total spending by Medicare in 2016 on the brand-name combination products was $232 million and the estimated spending for the generic constituents would have been $13 million, which is an estimated difference of $219 million. For the therapeutically equivalent generic substitutes category, total spending by Medicare in 2016 on the brand-name combination products was $491 million and the estimated spending for the generic constituents would have been $20 million, which is an estimated difference of $471 million. In 2016, the estimated spending for the generic constituents for these 29 drugs would have been $925 million less than the estimated spending for the brand-name combinations. For the 10 most costly combination products available during the entire study period, the listed Medicare spending could have been an estimated $2.7 billion lower between 2011 and 2016 if the generic constituents had been prescribed.

Conclusions and Relevance

In 2016, the difference between the amount that the Medicare drug benefit program reported spending on brand-name combination medications and the estimated spending for generic constituents for the same number of doses was $925 million. Promoting generic substitution and therapeutic interchange through prescriber education and more rational substitution policies may offer important opportunities to achieve substantial savings in the Medicare drug benefit program.

This retrospective analysis estimates the additional cost to Medicare of prescribing brand-name combination medications instead of generic constituents by using the Medicare data set of Part D beneficiaries prescribed any of the 1500 medications that accounted for highest total spending in 2015.

Introduction

The United States spends more per capita on prescription medications than other industrialized nations, and high drug costs are of increasing concern for patients, prescribers, policy makers, and payers.1,2,3 Because brand-name drugs make up the vast majority of US drug spending, using equally safe and effective lower-cost generic drugs represents an important opportunity to reduce unnecessary expenditures.4,5 This may be particularly important in the case of fixed-dose combination products.

One study of prescribing within a single, large national insurance system found that nearly 569 000 patients filled prescriptions for fixed-dose combination products to treat cardiovascular disease in 2012.6 Often promoted as providing increased convenience for patients,7,8 combination products are sometimes more expensive than the sum of their constituent parts,9,10,11 particularly when brand-name combination products are made from medications available as lower-cost generic drugs. As with other medications in the United States, the prices for these combination products are not determined by the magnitude of any incremental clinical benefit or the amount invested in research, development, or clinical trials; rather, initial prices are set by the manufacturer.1,12,13 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is prevented from negotiating prices with manufacturers on behalf of individual Part D plans and the plans are required by law to pay for all products in the following protected drug classes: immunosuppressants, antineoplastics, antiretrovirals, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants.14,15

The total cost to patients and payers of using expensive combination products in place of lower-cost generic constituents is not known. Using a data set made publicly available by the CMS, this study sought to estimate the annual incremental costs of using brand-name combination products compared with lower-cost generic constituents among Medicare Part D beneficiaries.

Methods

Data Set

The Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event data set used represents reported drug expenditures for the approximately 70% of beneficiaries enrolled in the Medicare drug benefit plan from 2011 through 2016.16 Citing privacy concerns, the CMS excluded any drug records for prescription medications for which there were fewer than 50 claims in 2016 or 10 or fewer claims within a calendar year between 2011 and 2015. The CMS does not require a data use agreement to access these deidentified data, and because this analysis was based on publicly available data and involved no individual patient health records, institutional review board approval was not required.17

Cohort Creation

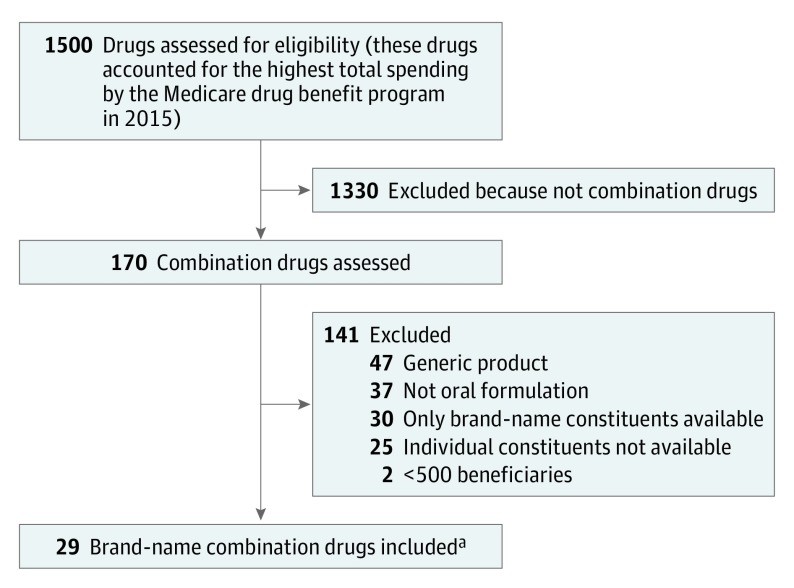

First, 1500 medications were identified that accounted for the highest total spending reported by Medicare in 2015 (Figure 1). Second, all oral brand-name fixed-dose combination medications were identified for which all constituents of the combination product had an active ingredient that was either available as a generic, as an over-the-counter product, or as a generic in the same class. In the case of a class-based (therapeutically equivalent) substitute, we reviewed the literature (including relevant society guidelines) to ensure there was no evidence of a substantial difference in clinical benefit with the use of one product compared with another.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram to Identify Study Drugs.

aThe study inclusion criteria were brand-name combination medication, oral (eg, pill, tablet, or capsule) formulation, and all constituents are generic drugs or have a therapeutically equivalent generic substitute. The exclusion criteria were device as part of the brand-name product (eg, inhaler), generic product became available after January 1, 2015, and fewer than 500 beneficiaries in 2015.

In addition, questions about the clinical use of specific medications were reviewed with relevant subspecialty content experts. We excluded any medications with fewer than 500 total beneficiaries in 2015. By including only oral medications, we excluded medications that incorporated devices such as an inhaler.

Variable Extraction

From the Medicare data set, the brand-name of each prescription medication was extracted along with its constituent parts, the number of beneficiaries prescribed each drug, the drug-specific total annual spending reported by Medicare, the number of units (eg, tablets) dispensed, and a claim-weighted mean price per dosage unit of the medication. In this data set, total spending includes amounts paid by the Medicare Part D plan as well as beneficiary payments, which vary depending on decisions made at the level of each Part D plan administrator.

For each combination drug, we defined its constituents. A claim-weighted mean price per unit was then extracted from the data set. For potentially substitutable over-the-counter medications (eg, acetaminophen) that were not available as individual products in the Medicare data set, an average pharmacy price from GoodRx.com (an online pharmaceutical price aggregator) was used.18,19

Outcomes and Data Analysis

The amount Medicare reported spending in 2016 for each brand-name combination product was compared with the estimated amount that would have been spent had constituent generic medications been prescribed instead for the same number of total doses. We also calculated the change in mean price for each combination product between 2011 and 2016. For medications that became available after 2011, we calculated the change in price between the year for which the data were first available and 2016.

The brand-name combination drugs were divided into the 3 mutually exclusive categories: constituents available as generic medications at identical doses, generic constituents at different doses, and therapeutically equivalent generic substitutes. For the 10 medications with the highest total spending in 2015 for which data were available for all years between 2011 and 2016, we calculated the cumulative amount that Medicare reported spending during that 6-year period and estimated the amount that would have been spent substituting generic products at their Medicare-reported prices.

Measures of variability could not be provided for the estimates reported because the main data set provides a single listed price for the combination product and a single price for each generic constituent. All costs were expressed in 2016 US dollars and account for medical inflation. The medical inflation rate was obtained from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Manufacturers sometimes provide Medicare with rebates off the list price for costly medications, but neither the CMS nor the manufacturer discloses the amount of such rebates for individual medications. The CMS has released a summary report that lists rebate amounts paid in 2014 and is aggregated by therapeutic drug class.20

We performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate how such rebates might affect potential savings during this 6-year period, assuming rebates of 0% (base case), 17.5% (the overall rebate rate reported by Medicare for brand-name drugs in 2014), and 26.3% (the highest rebate rate reported by Medicare for any therapeutic class in 2014). No rebates were assumed for generic medications. Calculations were performed using Excel software version 16.1 (Microsoft).

Results

Twenty-nine combination drugs met inclusion criteria and were included in the study and represent the following therapeutic areas: cardiovascular (n = 16 drugs), pain (n = 4), neurological (n = 3), 2 each for endocrine and infectious disease, and 1 each for urological and gastrointestinal (Figure 1 and Table 1). In 2016, the 3 most widely prescribed brand-name combination drugs were Benicar HCT (olmesartan and hydrochlorothiazide), Azor (amlodipine and olmesartan), and Nuedexta (dextromethorphan and quinidine). Data for 28 drugs (97%) were available for each year from 2011 through 2016; among these, the mean per-unit price reported by Medicare increased by 224% (range, 35%-1759%) during the study period.

Table 1. Characteristics of 29 Brand-name Combination Drugs Used in Medicare Part D in 2016.

| Brand-name Combination Drug | Generic Constituents | Therapeutic Area | No. of Medicare Beneficiaries in 2016a | Change in List Price Between 2011 and 2016b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of Increase/Pill, $c | % Increased | ||||

| Constituents Available as Generic Medications at Identical Doses Category | |||||

| Epzicom | Abacavir, lamivudine | Infectious disease | 15 713 | 11.43 | 36 |

| Bidil | Isosorbide dinitrate, hydralazine | Cardiovascular | 11 187 | 0.91 | 45 |

| Diovan HCT | Valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide | Cardiovascular | 7536 | 4.17 | 115 |

| Pylera | Bismuth, metronidazole, tetracycline | Infectious disease | 5814 | 2.51 | 75 |

| Exforge | Amlodipine, valsartan | Cardiovascular | 5036 | 4.29 | 109 |

| Percocet | Oxycodone, acetaminophen | Pain | 4097 | 9.58 | 206 |

| Hyzaar | Losartan, hydrochlorothiazide | Cardiovascular | 2902 | 1.25 | 39 |

| Micardis HCT | Telmisartan, hydrochlorothiazide | Cardiovascular | 2474 | 2.42 | 73 |

| Lotrel | Amlodipine, benazepril | Cardiovascular | 2405 | 3.86 | 87 |

| Fosamax Plus D | Alendronate, vitamin D3 | Endocrine | 2068 | 15.28 | 64 |

| Simcor | Extended-release niacin, simvastatin | Cardiovascular | 1967 | 2.50 | 82 |

| Exforge HCT | Amlodipine, valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide | Cardiovascular | 1517 | 4.35 | 109 |

| Zegerid | Omeprazole, sodium bicarbonate | Gastrointestinal | 1486 | 78.36 | 989 |

| Tarka | Trandolapril, extended-release verapamil | Cardiovascular | 1365 | 1.10 | 35 |

| Caduet | Amlodipine, atorvastatin | Cardiovascular | 1219 | 6.21 | 109 |

| Advicor | Extended-release niacin, lovastatin | Cardiovascular | 1056 | 3.03 | 80 |

| Avalide | Irbesartan, hydrochlorothiazide | Cardiovascular | 1047 | 3.57 | 110 |

| Arthrotec 75 | Diclofenac, misoprostol | Pain | 794 | 3.09 | 111 |

| Actoplus Met XR | Pioglitazone, extended-release metformin | Endocrine | 732 | 6.65 | 121 |

| Stalevo 100 | Carbidopa, levodopa, entacapone | Neurological | 295 | 2.87 | 88 |

| Generic Constituents at Different Doses Category | |||||

| Nuedexta | Dextromethorphan, quinidine | Neurological | 50 402 | 3.64 | 42 |

| Duexis | Ibuprofen, famotidine | Pain | 5907 | 18.65 | 1160 |

| Treximet | Sumatriptan, naproxen sodium | Neurological | 1878 | 57.60 | 256 |

| Therapeutically Equivalent Generic Substitutes Category | |||||

| Benicar HCT | Olmesartan, hydrochlorothiazide | Cardiovascular | 158 083 | 3.54 | 106 |

| Azor | Amlodipine, olmesartan | Cardiovascular | 54 139 | 4.05 | 105 |

| Tribenzor | Olmesartan, amlodipine, hydrochlorothiazide | Cardiovascular | 32 869 | 4.22 | 105 |

| Jalyn | Dutasteride, tamsulosin | Urological | 12 920 | 1.86 | 51 |

| Edarbyclor | Azilsartan, chlorthalidone | Cardiovascular | 11 805 | 2.53e | 90 |

| Vimovo | Naproxen, esomeprazole | Pain | 5958 | 28.48 | 1759 |

Indicates the number of unique Medicare enrollees who took this medication.

Reported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Mean price per dosage unit (pill, tablet, or other dosage form) weighted to account for variation in claims volume for different strengths, routes, and dosage forms.

Rounded to the nearest whole number.

Change in list price from 2012 to 2016.

Estimated Potential Differences in Medicare Spending

Medicare’s list price per pill for each combination product, Medicare’s list price of the generic constituents, and the estimated price differences if the constituents or therapeutically equivalent generic drugs had been used instead appear in Table 2.

Table 2. Reported Spending by Medicare Part D on Brand-name Combination Drugs and Estimated Potential Reduction in Spending by Substituting Generic Constituents in 2016.

| Brand-name Combination Drug | Generic Constituents | List Price, $a | Total Reported Spending on Brand-name Product, $c | Price of Generic Constituents/Price of Combination Product, %d | Estimated Potential Reduction in Spending, $c,e |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per Pillb | Generic Constituents | |||||

| Constituents Available as Generic Medications at Identical Doses Category | ||||||

| Epzicom | Abacavir, lamivudine | 42.85 | 14.01 | 157 504 662 | 33 | 106 008 707 |

| Percocet | Oxycodone, acetaminophen | 14.23 | 0.38 | 43 993 029 | 3 | 42 832 272 |

| Zegerid | Omeprazole, sodium bicarbonate | 86.29 | 0.47 | 28 255 198 | 1 | 28 106 005 |

| Diovan HCT | Valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide | 7.79 | 0.93 | 14 985 874 | 12 | 13 190 005 |

| Bidil | Isosorbide dinitrate, hydralazine | 2.93 | 0.88 | 13 866 434 | 30 | 9 700 493 |

| Exforge | Amlodipine, valsartan | 8.21 | 0.96 | 7 755 807 | 12 | 6 845 024 |

| Lotrel | Amlodipine, benazepril | 8.27 | 0.25 | 5 589 369 | 3 | 5 419 066 |

| Pylera | Bismuth, metronidazole, tetracycline | 5.86 | 5.27 | 4 234 402 | 90 | 425 805 |

| Caduet | Amlodipine, atorvastatin | 11.92 | 0.42 | 4 086 377 | 4 | 3 942 761 |

| Micardis HCT | Telmisartan, hydrochlorothiazide | 5.76 | 1.28 | 3 554 664 | 22 | 2 764 368 |

| Hyzaar | Losartan, hydrochlorothiazide | 4.47 | 0.25 | 3 501 615 | 6 | 3 303 564 |

| Actoplus Met XR | Pioglitazone, extended-release metformin | 12.16 | 1.35 | 2 754 836 | 11 | 2 421 828 |

| Exforge HCT | Amlodipine, valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide | 8.36 | 1.05 | 2 010 417 | 13 | 1 756 307 |

| Avalide | Irbesartan, hydrochlorothiazide | 6.81 | 0.46 | 1 959 401 | 7 | 1 826 769 |

| Fosamax Plus D | Alendronate, vitamin D3 | 39.05 | 1.25 | 1 875 014 | 3 | 1 814 983 |

| Arthrotec 75 | Diclofenac, misoprostol | 5.88 | 1.40 | 1 720 942 | 24 | 1 310 946 |

| Tarka | Trandolapril, extended-release verapamil | 4.22 | 0.78 | 1 671 759 | 18 | 1 362 704 |

| Stalevo 100 | Carbidopa, levodopa, entacapone | 6.13 | 2.65 | 1 509 886 | 43 | 856 799 |

| Simcor | Extended-release niacin, simvastatin | 5.53 | 2.68 | 1 023 636 | 48 | 536 956 |

| Advicor | Extended-release niacin, lovastatin | 6.82 | 2.71 | 723 072 | 40 | 434 939 |

| Subtotal | 302 576 394 | 234 860 301 | ||||

| Generic Constituents at Different Doses Category | ||||||

| Nuedexta | Dextromethorphan, quinidine | 12.30 | 0.69 | 200 379 706 | 6 | 189 139 209 |

| Duexis | Ibuprofen, famotidine | 20.26 | 0.28 | 23 775 067 | 1 | 23 446 423 |

| Treximet | Sumatriptan, naproxen sodium | 80.14 | 10.73 | 8 122 697 | 13 | 7 035 190 |

| Subtotal | 232 277 470 | 219 620 822 | ||||

| Therapeutically Equivalent Generic Substitutes Categoryf | ||||||

| Benicar HCT | Olmesartan, hydrochlorothiazide | 6.89 | 0.25 | 267 075 037 | 4 | 257 373 256 |

| Azor | Olmesartan, amlodipine | 7.90 | 0.28 | 104 347 177 | 4 | 100 645 971 |

| Tribenzor | Olmesartan, amlodipine, hydrochlorothiazide | 8.25 | 0.37 | 64 173 585 | 4 | 61 294 129 |

| Vimovo | Naproxen, esomeprazole | 30.10 | 0.35 | 32 354 888 | 1 | 31 978 635 |

| Edarbyclor | Azilsartan, chlorthalidone | 5.36 | 0.94 | 13 402 609 | 18 | 11 051 324 |

| Jalyn | Dutasteride, tamsulosin | 5.51 | 0.76 | 9 829 825 | 14 | 8 474 464 |

| Subtotal | 491 183 121 | 470 817 779 | ||||

| Total | 1.03 billion | 925 298 902 | ||||

Reported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Mean price per dosage unit (pill, tablet, or other dosage form) weighted to account for variation in claims volume for different strengths, routes, and dosage forms.

Rounded to the nearest dollar.

Rounded to the nearest whole number.

Based on list prices and does not account for possible rebates.

Losartan was substituted for olmesartan and azilsartan, omeprazole for esomeprazole, and finasteride for dutasteride.

For the 20 brand-name combination drugs in the category of having constituents available as generic medications at identical doses, the total spending reported by Medicare in 2016 for the brand-name combination products was $303 million and the estimated spending for the generic constituents would have been $68 million, which is an estimated difference of $235 million. An example from this category is the antihypertensive drug Exforge, which is a combination of amlodipine and valsartan, that cost $8.21 per pill in 2016 compared with a total of $0.96 for its generic constituents. For the 5036 beneficiaries prescribed Exforge in 2016, the estimated potential reduction in reported spending could have been $6.8 million.

For the 3 brand-name combination drugs in the category of having generic constituents at different doses (eg, Treximet, for the treatment of migraine headaches, contains 85 mg of sumatriptan but sumatriptan is only available as an individual product in doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg), the total spending reported by Medicare in 2016 for the brand-name combination products was $232 million and the estimated spending for the generic constituents would have been $13 million, which is an estimated difference of $219 million. An example from this category is Duexis, which is a combination of ibuprofen (800 mg) and the histamine-2 receptor antagonist famotidine (26.6 mg). In 2016, the Medicare-reported price was $20.26 per pill compared with a total of $0.28 for generic ibuprofen and famotidine (available in doses of 20 mg and 40 mg). For the 5907 beneficiaries prescribed Duexis in 2016, the estimated potential reduction in reported spending could have been $23.4 million.

The third drug in this generic constituents at different doses category is Nuedexta, which is approved for the treatment of pseudobulbar affect and is often prescribed for behavioral symptoms in patients with dementia. It is a combination of dextromethorphan (available as an over-the-counter cough suppressant) and low-dose quinidine (10 mg) that is added to slow the metabolism of the dextromethorphan. The mean reported Medicare expenditure for Nuedexta in 2016 was $12.30 per pill. In the United States, the lowest available dose of quinidine is 200 mg ($0.26 per pill). If a lower dose of quinidine were available at the price of $0.26 per pill and prescribed with dextromethorphan for the 50 402 beneficiaries who filled prescriptions for Nuedexta, the estimated potential reduction in reported spending could have been $189.1 million.

For the 6 brand-name combination products in the category of having therapeutically equivalent generic substitutes, the total spending reported by Medicare in 2016 for the brand-name combination products was $491 million and the estimated spending for the generic constituents would have been $20 million, which is an estimated difference of $471 million. An example from this category is the antihypertensive medication Edarbyclor, which is a combination of the angiotensin receptor blocker azilsartan (Edarbi) and chlorthalidone and was priced at $5.36 per pill in 2016. If the generic angiotensin receptor blocker losartan had been substituted for azilsartan and prescribed with chlorthalidone, the cost would have been $0.94 per pill. For the 11 805 beneficiaries prescribed Edarbyclor in 2016, the estimated potential reduction in reported spending could have been $11 million.

Cumulative Estimated Reduction in Spending

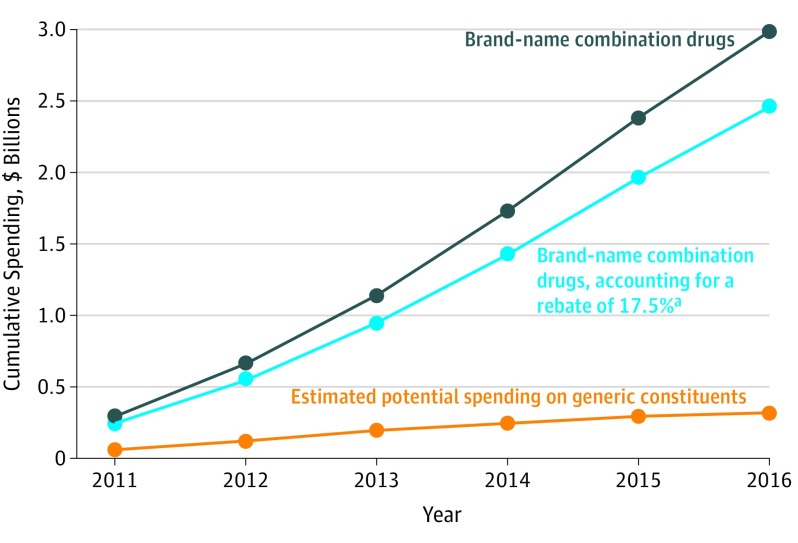

Adding these 3 categories together, data on expenditures reported by the Medicare drug benefit program indicate that the estimated difference between the amount spent on the brand-name combination products and the prices of individual generic or over-the-counter drugs if used for the same number of doses was $925 million in 2016. For the 10 most costly brand-name combination products in 2015 that were available during the 6-year study period (excluding Nuedexta given that dose differences make it impractical for a clinician to have made that substitution), cumulative spending by Medicare exceeded $2.9 billion between 2011 and 2016.

Spending could have been reduced by an estimated $2.7 billion between 2011 and 2016 if the generic constituents had been prescribed (Figure 2). If rebates had been paid by manufacturers at the average Medicare-reported rate of 17.5%, the estimated reduction in spending would have been $2.1 billion over 6 years. If a rebate of 26.3% had been applied, the estimated potential reduction in reported spending could have been $1.9 billion.

Figure 2. Reported Cumulative Spending by Medicare Part D on the 10 Most Costly Brand-name Combination Drugs Compared With Estimated Potential Spending on Generic Constituents Between 2011 and 2016.

Includes the 10 most costly brand-name combination drugs for which data are available for the 6-year period: Benicar HCT, Azor, Tribenzor, Jalyn, Vimovo, Percocet, Duexis, Zegerid, Bidil, and Treximet. All values adjusted to 2016 dollars, accounting for medical inflation. Excludes Nuedexta, given that dose differences make it impractical for a clinician to have made that substitution.

aThe blue curve represents Medicare-reported expenditures (black curve) minus the value of manufacturer rebates, estimated at 17.5%. The difference between the blue curve and the estimated expenditures for generic constituents (orange curve) represents the potential cost savings of $2.1 billion over 6 years if generic constituents had been used.

Discussion

In 2016, the total potential reduction in Medicare spending for brand-name combination drugs was estimated at $925 million lower if generic products had been prescribed at the same doses ($235 million), at different doses ($219 million), and if therapeutically equivalent generic medications had been prescribed ($471 million). For the 10 most costly brand-name combination drugs, the cumulative potential reduction in spending between 2011 and 2016 was estimated at $2.7 billion. Taking into account possible rebates from manufacturers at the average rate reported by Medicare, potential savings would have been estimated at $2.1 billion in total.

Combination products reduce a patient’s pill burden, and in theory can improve adherence. However, a clear connection between combination products, improved adherence, and improved clinical outcomes has not been solidly established. The FOCUS Project tested the benefits of a polypill combining aspirin, simvastatin, and ramipril compared with the 3 drugs given separately to prevent cardiovascular events. The combination product resulted in a modest improvement in adherence (41.0% in the control group compared with 50.8% in the polypill group, P = .02), though no difference was found in mean blood pressure or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level during the 9 months of follow-up.21 A 2017 Cochrane review concluded that the benefits of combination products on mortality or cardiovascular events were uncertain.22 In contrast, the larger co-payments that are often seen with more expensive products have been demonstrated to reduce adherence and worsen clinical outcomes.23,24

A substantial potential reduction in spending would have been associated with the 6 combination products for which in-class generic therapeutic substitution was possible. Four combinations incorporated a brand-name angiotensin receptor blocker, which is a class with similar clinical effects.25,26 The other 2 therapeutic substitutions would have exchanged omeprazole for esomeprazole (in Vimovo) and finasteride for dutasteride (in Jalyn).

Meta-analyses have not found significant differences in efficacy for symptom relief among patients taking different proton pump inhibitors.27,28 Similarly, an evaluation of dutasteride and finasteride found no compelling data to suggest efficacy differences between the 2 drugs.29

For pharmaceutical manufacturers, creating new brand-name combination products offers an opportunity to extend market exclusivity.30 In an analysis of US Food and Drug Administration approvals of fixed-dose combination products over 3 decades, Hao et al31 found that manufacturers tend to market combination products “shortly before the generic version of the single active ingredient drug enters the US market.” The number of combination drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration that contain drugs already on the market has been increasing steadily from an average of 1.2 approvals of such drugs per year in the 1980s to 2.5 per year in the 1990s, 5.9 per year in the 2000s, and 7 per year from 2010 through 2012.31

Nuedexta was the only combination drug studied with an active ingredient constituent (quinidine) not available in a dose that was similar or identical to the dose used in the combination product. Approved for the treatment of pseudobulbar affect based on studies of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or multiple sclerosis, this drug is often prescribed to treat agitation among patients with dementia for which its benefit-risk relationship is controversial.32 Quinidine is available generically at 200 mg rather than the 10 mg used in Nuedexta,33 and it would be impractical to ask patients to split these tablets to achieve this dose. However, this brand-name drug contributes $189 million to the potential spending differential in 2016, and Nuedexta is a compelling example of the price differential between a recently introduced brand-name combination and its constituent parts.

Prior studies have evaluated the difference in costs between combination products and their constituents for some specific categories such as antihypertensive medications.10 In a prior study based on 2004 spending data, out-of-pocket costs for 24 of the 27 combination products were substantially higher than the cost for the generic constituents; however, the total costs were lower for the combination products on average.

The different results in this study may reflect that prices of brand-name drugs have increased considerably in recent years, whereas generic prices continue to decrease. This study also included drugs from among the 1500 most costly to Medicare, identifying a subset of brand-name products with the greatest potential for substantial savings.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the CMS is prohibited from publicly disclosing rebate amounts for individual drugs; however, recent data on aggregate rebate amounts allow reasonable estimates of prices after rebates.

Second, the prices are an average-weighted price by dose; a direct comparison of identical doses was not available. This is unlikely to have a substantial effect on these findings because commonly used doses or those very close to them were used in all but 1 of the combination drugs studied.

Third, this analysis assumed that substitution was possible in all cases. For small subsets of patients, there may be legitimate clinical reasons to use a specific drug rather than using therapeutic substitution.34 From this data set, we cannot determine if patients had previously tried any generic products before being switched.

Conclusions

In 2016, the difference between the amount that the Medicare drug benefit program reported spending on brand-name combination medications and the estimated spending for generic constituents for the same number of doses was $925 million. Promoting generic substitution and therapeutic interchange through prescriber education and more rational substitution policies may offer important opportunities to achieve substantial savings in the Medicare drug benefit program.

References

- 1.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858-871. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanavos P, Ferrario A, Vandoros S, et al. Higher US branded drug prices and spending compared to other countries may stem partly from quick uptake of new drugs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(4):753-761. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319(10):1024-1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choudhry NK, Denberg TD, Qaseem A, et al. Improving adherence to therapy and clinical outcomes while containing costs: opportunities from the greater use of generic medications. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(1):41-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen ME, Richardson C. Estimation of potential savings through therapeutic substitution. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):769-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang B, Choudhry NK, Gagne JJ, et al. Availability and utilization of cardiovascular fixed-dose combination drugs in the United States. Am Heart J. 2015;169(3):379-386.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottwald-Hostalek U, Sun N, Barho C, et al. Management of hypertension with a fixed-dose (single-pill) combination of bisoprolol and amlodipine. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2017;6(1):9-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan F, Chernew ME, Fendrick AM. Impact of fixed-dose combination drugs on adherence to prescription medications. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):611-614. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0544-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hakim A, Ross JS. High prices for drugs with generic alternatives. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):305-306. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabbani A, Alexander GC. Out-of-pocket and total costs of fixed-dose combination antihypertensives and their components. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(5):509-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollack A. Drug makers sidestep barriers on pricing. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/20/business/drug-makers-sidestep-barriers-on-pricing.html. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- 12.Avorn J. The $2.6 billion pill. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1877-1879. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keyhani S, Diener-West M, Powe N. Are development times for pharmaceuticals increasing or decreasing? Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(2):461-468. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarpatwari A, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. An incomplete prescription. JAMA. 2018;319(23):2373-2374. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation The Medicare part D prescription drug benefit. https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/the-medicare-prescription-drug-benefit-fact-sheet/. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare part D drug spending dashboard and data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/MedicarePartD.html. Accessed July 16, 2018.

- 17.Definitions, 45 CFR §46.102 (2004).

- 18.Arora S, Sood N, Terp S, Joyce G. The price may not be right. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(7):410-415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinke T. After a big entrance, it’s just so-so for Entresto. Manag Care. 2017;26(7):17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2014 Medicare part D rebate summary. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/PartD_Rebates.html. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- 21.Castellano JM, Sanz G, Peñalvo JL, et al. A polypill strategy to improve adherence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(20):2071-2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahiru E, de Cates AN, Farr MR, et al. Fixed-dose combination therapy for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD009868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, Avorn J, et al. At Pitney Bowes, value-based insurance design cut copayments and increased drug adherence. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(11):1995-2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ, et al. Full coverage for preventive medications after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2088-2097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1107913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abraham HMA, White CM, White WB. The comparative efficacy and safety of the angiotensin receptor blockers in the management of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases. Drug Saf. 2015;38(1):33-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dézsi CA. The different therapeutic choices with ARBs. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2016;16(4):255-266. doi: 10.1007/s40256-016-0165-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(3):308-328. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gralnek IM, Dulai GS, Fennerty MB, et al. Esomeprazole versus other proton pump inhibitors in erosive esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(12):1452-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Avins AL, et al. Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/benign-prostatic-hyperplasia-(2010-reviewed-and-validity-confirmed-2014). Accessed July 10, 2018.

- 30.Halo Pharma Halo Pharma partners with pharmaceutical companies to formulate and manufacture a broad range of fixed-dose combination drug products. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20171102005065/en/Halo-Pharma-Partners-Pharmaceutical-Companies-Formulate-Manufacture. Accessed January 18, 2018.

- 31.Hao J, Rodriguez-Monguio R, Seoane-Vazquez E. Fixed-dose combination drug approvals, patents and market exclusivities compared to single active ingredient pharmaceuticals. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cummings JL, Lyketsos CG, Peskind ER, et al. Effect of dextromethorphan-quinidine on agitation in patients with Alzheimer disease dementia. JAMA. 2015;314(12):1242-1254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bozic B, Uzelac TV, Kezic A, et al. The role of quinidine in the pharmacological therapy of ventricular arrhythmias quinidine. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2018;18(6):468-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makani H, Bangalore S, Supariwala A, et al. Antihypertensive efficacy of angiotensin receptor blockers as monotherapy as evaluated by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(26):1732-1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]