Abstract

This cohort study compares antibiotic prescribing in 2014 among retail clinics, urgent care centers, emergency departments, and traditional medical offices in the United States.

Antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance and is associated with adverse events, including Clostridium difficile infections.1 Antibiotic overuse, especially for viral respiratory infections, is common.2 Only 60% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions dispensed in the United States are written in traditional ambulatory care settings (hereinafter “medical offices”) and emergency departments (EDs).2 Growing markets, including urgent care centers and retail clinics, may contribute to the remaining 40%.3,4 Our objective was to compare antibiotic prescribing among urgent care centers, retail clinics, EDs, and medical offices.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the 2014 Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, which captures claims data on individuals younger than 65 years with employer-sponsored insurance.5 The National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases human subjects advisor deemed these to be deidentified data and thus exempt from ethical approval and patient written informed consent.

Outpatient claims with facility codes for urgent care center, retail clinic, hospital-based ED, or medical office were included. We included all visits for which medical and prescription coverage data were captured for the months of, prior to, and following the visit (except December 2014 visits). We excluded visits for which diagnoses were missing or for patients with recent hospitalizations or recent outpatient systemic antibiotic prescription fills.

Each visit was assigned a single diagnosis using a previously described, tiered system of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes.2 Data on systemic (oral and parenteral) antibiotic prescriptions, identified using national drug codes from the 2016 Truven Health Red Book supplement, were extracted from outpatient pharmaceutical claims. Oral antibiotic prescriptions were linked to each enrollee’s most recent outpatient visit within 3 days.6 Parenteral antibiotics were linked to same-day outpatient visits. The unit of analysis was unique visits, and the outcome was percentage of visits linked to prescription of antibiotics, stratified by setting and diagnosis. We focused on antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses (ie, diagnoses for which antibiotics are unnecessary based on clinical practice guidelines: viral upper respiratory infection, bronchitis/bronchiolitis, asthma/allergy, influenza, nonsuppurative otitis media, and viral pneumonia).2 Exact confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using binomial distributions. Analyses were conducted using DataProbe 5.0 (Truven Health Analytics) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

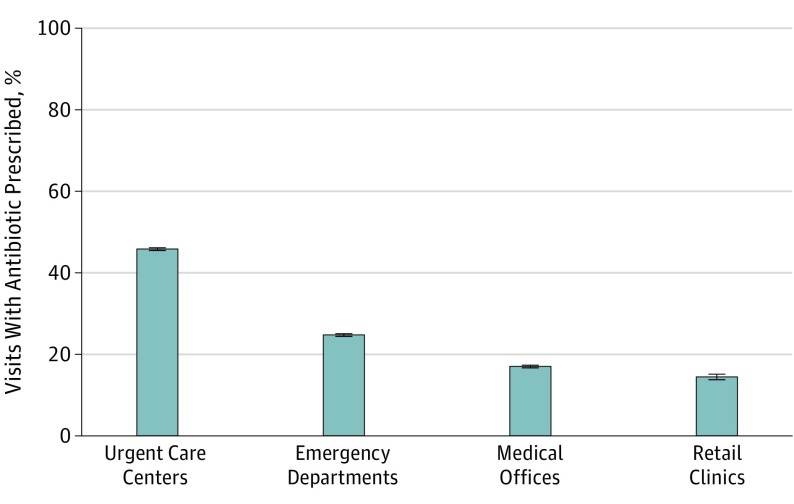

Antibiotic prescriptions were linked to 39.0% (n = 1 062 477) of 2.7 million urgent care center visits (95% CI, 39.0%-39.1%), 36.4% (n = 21 177) of 58 206 retail clinic visits (95% CI 36.0%-36.8%), 13.8% (n = 660 450) of 4.8 million ED visits (95% CI 13.8%-13.8%), and 7.1% (n = 10 580 312) of 148.5 million medical office visits (95% CI 7.1%-7.1%) (Table). Visits for antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses accounted for 17% (n = 10 009) of retail clinic visits, 16% (n = 441 605) of urgent care center visits, 6% (n = 9 203 276) of medical office visits, and 5% (n = 257 010) of ED visits. Among visits for antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses, antibiotic prescribing was highest in urgent care centers (45.7%; n = 201 682), followed by EDs (24.6%; n = 63 189), medical offices (17.0%; n = 1 563 573), and retail clinics (14.4%; n = 1444) (Figure).

Table. Antibiotic Prescribing for Select Diagnoses Across the 4 Ambulatory Care Settings.

| Diagnosis | Urgent Care Center | Retail Clinic | Emergency Department | Medical Office | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits, No. (% of Total Visits) | Antibiotic Prescribing, % (95% CI) | Visits, No. (% of Total Visits) | Antibiotic Prescribing, % (95% CI) | Visits, No. (% of Total Visits) | Antibiotic Prescribing, % (95% CI) | Visits, No. (% of Total Visits) | Antibiotic Prescribing, % (95% CI) | |

| Antibiotic almost always indicateda | ||||||||

| Urinary tract infection | 109 449 (4.0) | 79.8 (79.6-80.0) | 2271 (3.9) | 86.5 (85.0-87.9) | 143 793 (3.0) | 66.6 (66.4-66.9) | 904 819 (0.6) | 67.0 (66.9-67.1) |

| Pneumonia | 17 393 (0.6) | 83.0 (82.4-83.5) | 127 (0.2) | 91.3 (85.0-95.6) | 33 786 (0.7) | 66.4 (65.9-66.9) | 168 677 (0.1) | 75.2 (75.0-75.4) |

| Antibiotic may be indicatedb | ||||||||

| Pharyngitis | 316 202 (11.6) | 59.7 (59.6-59.9) | 8512 (14.6) | 56.5 (55.5-57.6) | 111 645 (2.3) | 46.7 (46.4-47.0) | 2 585 533 (1.7) | 51.3 (51.3-51.4) |

| Sinusitis | 301 363 (11.1) | 82.2 (82.1-82.4) | 9317 (16.0) | 86.9 (86.2-87.6) | 53 097 (1.1) | 67.5 (67.2-68.0) | 2 992 565 (2.0) | 76.0 (75.9-76.0) |

| Acute otitis media | 96 915 (3.6) | 82.8 (82.5-83.0) | 3369 (5.8) | 85.5 (84.3-86.7) | 52 131 (1.1) | 71.9 (71.6-72.3) | 1 194 365 (0.8) | 79.1 (79.0-79.1) |

| Antibiotic-inappropriate diagnosesc | ||||||||

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 207 079 (7.6) | 41.6 (41.4-41.8) | 5336 (9.2) | 10.5 (9.7-11.3) | 95 287 (2.0) | 18.7 (18.5-19.0) | 2 308 891 (1.6) | 29.9 (29.8-29.9) |

| Bronchitis and/or bronchiolitis | 115 542 (4.2) | 75.8 (75.5-76.0) | 1556 (2.7) | 31.1 (28.8-33.5) | 59 702 (1.2) | 56.6 (56.2-57.0) | 798 703 (0.5) | 73.1 (73.0-73.2) |

| Asthma/Allergy | 52 523 (1.9) | 20.5 (20.1-20.8) | 1210 (2.1) | 6.1 (4.8-7.6) | 73 281 (1.5) | 11.2 (11.0-11.5) | 5 484 557 (3.7) | 3.2 (3.2-3.2) |

| Influenza | 44 427 (1.6) | 12.8 (12.5-13.1) | 1214 (2.1) | 3.8 (2.8-5.0) | 25 516 (0.5) | 7.9 (7.6-8.3) | 240 379 (0.2) | 11.4 (11.3-11.6) |

| Nonsuppurative otitis media | 21 966 (0.8) | 52.2 (51.6-52.9) | 693 (1.2) | 40.7 (37.0-44.5) | 3012 (0.1) | 41.7 (39.9-43.5) | 369 086 (0.2) | 23.6 (23.4-23.7) |

| Viral pneumonia | 68 (<0.1) | 72.1 (59.9-82.3) | 0 | 0 | 212 (<0.1) | 21.7 (16.4-27.9) | 1660 (<0.1) | 57.5 (55.1-59.9) |

| All diagnoses | 2 723 316 | 39.0 (39.0-39.1) | 58 206 | 36.4 (36.0-36.8) | 4 781 047 | 13.8 (13.8-13.8) | 148 453 330 | 7.1 (7.1-7.1) |

Miscellaneous bacterial infections not shown.

Acne; gastrointestinal infections; and skin, cutaneous, and mucosal infections not shown.

Miscellaneous other nonbacterial infections; other gastrointestinal conditions; other skin, cutaneous, and mucosal conditions; other genitourinary conditions; other respiratory conditions; and all other codes not listed elsewhere not shown.

Figure. Percentage of Visits for Antibiotic-Inappropriate Respiratory Diagnoses Leading to Antibiotic Prescriptions.

Antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses include viral upper respiratory infections, bronchitis and/or bronchiolitis, asthma and/or allergy, influenza, nonsuppurative otitis media, and viral pneumonia. Respective sample sizes are as follows: urgent care centers, n = 441 605; emergency departments, n = 257 010; medical offices (traditional ambulatory care), n = 9 203 276; and retail clinics, n = 10 009. Error bars indicated 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

There was substantial variability between settings in the percentage of visits at which antibiotics were prescribed among all visits and among visits for antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses. These patterns suggest differences in case mix and evidence of antibiotic overuse, especially in urgent care centers. This finding is important because urgent care and retail clinic markets are growing. Previous work demonstrated that in the 2010-2011 period at least 30% of antibiotic prescriptions written in physician offices and EDs were unnecessary.2 The finding of the present study that antibiotic prescribing for antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses was highest in urgent care centers suggests that unnecessary antibiotic prescribing nationally in all outpatient settings may be higher than the estimated 30%.

This analysis has limitations. Misclassification was possible because we could not clinically validate ICD-9-CM code diagnoses in claims data. These data are from a convenience sample and not generalizable to populations not captured in MarketScan.5 We used facility codes but could not validate whether facilities were actually urgent care centers, retail clinics, EDs, or medical offices. Since claims data do not link antibiotics to visits or diagnoses, assumptions were required to attribute 1 diagnosis to prescribed antibiotics.

Antibiotic stewardship interventions could help reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions in all ambulatory care settings, and efforts targeting urgent care centers are urgently needed.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/. Accessed December 30, 2016.

- 2.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashwood JS, Reid RO, Setodji CM, Weber E, Gaynor M, Mehrotra A. Trends in retail clinic use among the commercially insured. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(11):e443-e448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healthcare AMN. Convenient care: growth and staffing trends in urgent care and retail medicine. https://www.amnhealthcare.com/uploadedFiles/MainSite/Content/Healthcare_Industry_Insights/Industry_Research/AMN%2015%20W001_Convenient%20Care%20Whitepaper(1).pdf. Accessed December 30, 2016.

- 5.Hansen LG, Chang S White paper health research data for the real world: the MarketScan Databases. 2011. http://truvenhealth.com/portals/0/assets/PH_11238_0612_TEMP_MarketScan_WP_FINAL.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- 6.Vaz LE, Kleinman KP, Raebel MA, et al. Recent trends in outpatient antibiotic use in children. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):375-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]