Key Points

Question

Is cataract surgery associated with reduced serious traffic crashes as a driver?

Findings

In this population-based, study of 559 546 patients who received at least 1 eye cataract surgery, the crash rate decreased from 2.36 per 1000 patient-years in the baseline interval to 2.14 per 1000 patient-years after surgery, representing a 9% reduction in serious traffic crashes.

Meaning

These results suggest cataract surgery is associated with a patient’s reduced subsequent risk of serious traffic crash as a driver.

Abstract

Importance

Cataracts are the most common cause of impaired vision worldwide and may increase a driver’s risk of a serious traffic crash. The potential benefits of cataract surgery for reducing a patient’s subsequent risk of traffic crash are uncertain.

Objective

To conduct a comprehensive longitudinal analysis testing whether cataract surgery is associated with a reduction in serious traffic crashes where the patient was the driver.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population-based individual-patient self-matching exposure-crossover design in Ontario, Canada, between April 1, 2006, and March 31, 2016. Consecutive patients 65 years and older undergoing cataract surgery (n = 559 546).

Interventions

First eye cataract extraction surgery (most patients received second eye soon after).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Emergency department visit for a traffic crash as a driver.

Results

Of the 559 546 patients, mean (SD) age was 76 (6) years, 58% were women (n = 326 065), and 86% lived in a city (n = 481 847). A total of 4680 traffic crashes (2.36 per 1000 patient-years) accrued during the 3.5-year baseline interval and 1200 traffic crashes (2.14 per 1000 patient-years) during the 1-year subsequent interval, representing 0.22 fewer crashes per 1000 patient-years following cataract surgery (odds ratio [OR], 0.91; 95% CI, 0.84-0.97; P = .004). The relative reduction included patients with diverse characteristics. No significant reduction was observed in other outcomes, such as traffic crashes where the patient was a passenger (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.96-1.12) or pedestrian (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.88-1.17), nor in other unrelated serious medical emergencies. Patients with younger age (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.13-1.14), male sex (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.46-1.85), a history of crash (baseline OR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.94-4.02; induction OR, 4.26; 95% CI, 2.01-9.03), more emergency visits (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.19-1.52), and frequent outpatient physician visits (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01-1.36) had higher risk of subsequent traffic crashes (multivariable model).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study suggests that cataract surgery is associated with a modest decrease in a patient’s subsequent risk of a serious traffic crash as a driver, which has potential implications for mortality, morbidity, and costs to society.

This population-based study assesses whether cataract surgery is associated with a reduction in serious traffic crashes where the patient was the driver.

Introduction

Traffic crashes are a widespread cause of death and disability. About 1 person in 50 will have an incident in an average year, where 1% will die, 10% will be hospitalized, and 25% will be temporarily disabled.1,2 Worldwide, traffic crashes account for 1.2 million deaths annually and the direct economic costs globally are estimated at $518 billion annually.3 Traffic crashes are multifactorial in cause, with driver error contributing to most events.4 Drivers 65 years and older have the highest death rate per mile driven, in part owing to increased fallibility and frailty.5

Cataracts are a leading cause of impaired vision worldwide.6,7,8,9,10,11 The lifetime incidence of cataracts in the United States is 60% to 70%, and risk factors include older age, diabetes mellitus, traumatic injury, and steroid use.10,12 Early symptoms include decreased visual acuity, loss of contrast sensitivity, poor night vision, and increased glare.12,13,14,15 Currently, 25 million American individuals older than 65 years are diagnosed as having cataracts, and 3 million cataract surgeries are performed annually.10,16,17 Demographic trends and technology advances have made cataract extraction the most common surgical procedure in the United States owing to reliable outcomes and infrequent complications.10,16,17,18

Cataracts may cause insidious vision loss that could increase traffic risks for drivers.19,20,21 Published case-control analyses, a nonrandomized cohort study, self-reported surveys, and simulation studies suggest that patients diagnosed with cataracts have more driving difficulties and worse driving performance than average adults.15,22,23,24,25,26 However, the effectiveness of surgery for improving driving safety is uncertain because past research is limited by small sample sizes, brief follow-up durations, restricted patient samples, confounding by indication, and a focus on surrogate outcomes.27,28,29 We applied a self-matched crossover design to test whether cataract surgery is associated with a reduced risk of serious traffic crashes for drivers 65 years and older.

Methods

Study Setting

The study was approved by the Sunnybrook Research Ethics Board, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and conducted using privacy standards of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences including a waiver for individual consent. At the study midpoint (2011), Ontario’s population was 13 263 500, of whom 9 367 609 were licensed drivers involved in 177 039 total reported crashes (includes death, injury, and property damage).30 A total of 17 642 of these crashes resulted in the driver receiving emergency care, equal to 1.88 events per 1000 drivers annually. Throughout the study, patients received fully funded emergency care, physician services, diagnostic procedures, hospital admissions, outpatient clinic access, and prescription medications and were available for analysis.31,32,33 During the study, the overall rate of first eye cataract surgery was 298 per 1000 individuals 65 years and older.34,35

Medical Care

Demographic information, physician use, drug prescriptions, and discharge summaries for hospital services were collated through unique patient identifiers from health services databases.31,32 Validation of these databases has been performed.33,36,37,38 The data did not include the indication for cataract surgery, contralateral eye status, visual acuity, functional status, or driving license status.

Patient Selection

Consecutive patients receiving first eye cataract surgery were enrolled between April 1, 2006, and March 31, 2016, based on the physician procedure code (Ontario Health Insurance Plan code E140).9,31,39,40,41 The start date provided a minimum 4 years of observation before surgery for each patient. The end date provided a minimum 1-year follow-up after surgery for each patient. We excluded patients younger than 65 years because of the lower frequency of cataracts in younger patients and incomplete database information. We excluded patients undergoing cataract surgery combined with retinal, glaucoma, or corneal surgery because of uncertain visual recovery. Patients undergoing second cataract surgery were analyzed according to first operation.

Patient Characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics on the date of surgery included age, sex, socioeconomic quintile, home location, indicator for long-term care, and indicator of a physician warning about driving.36 Ophthalmologic history included past corneal, glaucoma, or retinal surgeries; past intravitreal injections or laser procedures; past ocular injury; and sustained visual field testing in the past 4 years.42 Additional medical history included diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes, depression, anxiety, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, heart failure, and myocardial infarction (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10]).43,44,45 Health care use for the full year prior to surgery included hospitalizations, emergency visits, prescription drugs, and outpatient encounters (ophthalmology and nonophthalmology). Wait time for surgery was defined from the date of initial assessment (code A235 or A253). Wait time from consultation request to initial assessment was not available.

Traffic Crashes as a Driver

We identified traffic crashes that resulted in emergency department treatment from validated suffixes that distinguished mechanisms of trauma (ICD-10 codes V01 to V69).46 We included individuals involved as a driver of a motor vehicle, motorcycle, or bicycle and excluded cases where the patient was a passenger or pedestrian. This definition does not include minor incidents that did not require emergency medical care or fatal crashes where death was declared at the scene. Patients who had more than 1 traffic crash were retained for each incident. Information on driving record, distance traveled, driver testing, delegated driving, and roadway infractions was not available.

Self-matching Design

The analysis used a self-matched design where each patient served as his or her own control (exposure crossover analysis).47,48 This design avoids confounding from genetics, personality, education, habits, or other stable characteristics (measured or unmeasured). A limitation of the design is that acute changes in health may temporarily increase (from impairments) or decrease (from reduced travel) traffic risks because of driver compensation; as a consequence, we defined the 6 months immediately prior to cataract surgery as a separate induction interval of possible shifting exposures.49 Another important consideration was that driving and health change with age; as a consequence, we collected an extended baseline interval and included secondary analyses for temporal time trends within generalized estimated equations (GEE) models.47,50,51

Time Intervals

We accrued 5 years of observation for each patient organized as 28-day segments to guarantee an identical number of weekends and weekdays in each segment (hereafter termed a month). We defined all months after surgery as the subsequent interval, the 6 months immediately before surgery as the induction interval, and all remaining earlier months as the baseline interval.48,49 The induction interval was defined a priori as 6 months based on the profile of improved visual function and quality of life for patients who waited less than 6 months for surgery, because the government benchmark for cataract surgery wait time was 4 months, and to avoid selection bias from health fluctuation and illness which could delay cataract surgery.52,53,54

Secondary Outcomes and Robustness

Secondary analyses explored emergency care for traffic crashes as passengers or as pedestrians (control analyses). To test for other functional outcomes, we evaluated emergency department visits for separate medical events: falls, hip fractures, ankle sprains, and depression. To test for further statistical artifacts and potential selection bias, we analyzed health care use defined by total medical emergencies. Additional subgroup analyses checked for potential survivor bias (by excluding all patients who did not survive for at least 1 year following cataract surgery) and whether driving restriction might explain the results (by excluding patients who received a formal physician medical warning against driving).55,56

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis compared each patient’s baseline with subsequent interval. The statistical association was calculated using parsimonious longitudinal GEE analyses.47,49,57 The induction interval was examined for descriptive purposes only. All patient characteristics were subjected to subgroup analyses to check robustness, and an additional multivariable explanatory model tested the association of baseline characteristics with overall crash risk (univariable screen approach). Secondary analyses included GEE allowing for a time variable to account for trending baselines.58 All P values were 2-tailed, accompanied by 95% confidence intervals, and not adjusted for multiple comparisons. A P value of .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Patient Characteristics

We identified 559 546 total patients. The mean age was 76 years, 58% were women (n = 326 065), and 86% lived in a city (n = 481 847) (Table 1). In total, 71% had their second eye surgery less than a year after their first eye (median of 35 days between surgeries). Patients were widely distributed through the enrolment interval and from all socioeconomic quintiles. Most had routine cataract surgery, with few undergoing anterior vitrectomy (0.4%). Very few patients had previous corneal, glaucoma, retinal surgery, intensive visual field testing, or retinal laser/injections. Almost no patients had received a formal medical warning about fitness to drive from their physician. The mean delay for cataract surgery could not be estimated accurately owing to the large counts of ambiguous waiting times.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Patient Demographics | Enrollment Period, No. (%)a | |

|---|---|---|

| First 5 y (n = 279 402) | Second 5 y (n = 280 144) | |

| Age, y | ||

| 66-75 | 133 568 (47.8) | 144 847 (51.7) |

| ≥76 | 145 834 (52.2) | 135 297 (48.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 114 076 (40.8) | 119 405 (42.6) |

| Female | 165 326 (59.2) | 160 739 (57.4) |

| Home locationb | ||

| Urban | 240 348 (86.0) | 241 499 (86.2) |

| Rural | 38 964 (13.9) | 38 511 (13.7) |

| Socioeconomic quintilec | ||

| Lowest | 54 892 (19.6) | 50 857 (18.2) |

| Next to lowest | 59 359 (21.2) | 56 875 (20.3) |

| Middle | 55 271 (19.8) | 55 617 (19.9) |

| Next to highest | 54 401 (19.5) | 57 767 (20.6) |

| Highest | 54 582 (19.5) | 58 068 (20.7) |

| Ocular history | ||

| Intravitreal injectiond | 2789 (1.0) | 5 965 (2.1) |

| Previous ocular surgerye | 9280 (3.3) | 12 367 (4.4) |

| Retinal surgery | 6436 (2.3) | 9965 (3.6) |

| Retinal laser | 2 378 (0.9) | 1970 (0.7) |

| Cornea surgery | 790 (0.3) | 1198 (0.4) |

| Glaucoma surgery | 545 (0.2) | 417 (0.1) |

| Previous ocular injuryf | 6182 (2.2) | 3862 (1.4) |

| Visual field tests (≥3)g | 22 412 (8.0) | 23 637 (8.4) |

| Wait timeh | ||

| Ambiguous | 148 335 (53.1) | 28 947 (10.3) |

| Short (≤6 mo) | 76 315 (27.3) | 148 721 (53.1) |

| Long (>6 mo) | 54 752 (19.6) | 102 476 (36.6) |

| Medical history | ||

| Diabetesi | 70 616 (25.3) | 76 727 (27.4) |

| Hypertensionj | 164 577 (58.9) | 148 611 (53.0) |

| Emphysemak | 26 541 (9.5) | 26 115 (9.3) |

| Depressionl | 10 617 (3.8) | 10 845 (3.9) |

| Anxietym | 55 591 (19.9) | 47 858 (17.1) |

| Hypothyroidismn | 11 843 (4.2) | 11 813 (4.2) |

| Osteoarthritiso | 80 593 (28.8) | 72 547 (25.9) |

| Congestive heart failurep | 19 222 (6.9) | 18 318 (6.5) |

| Myocardial infarctionq | 49 232 (17.6) | 40 523 (14.5) |

| Total outpatient visitsr | ||

| ≤6 | 63 898 (22.9) | 78 003 (27.8) |

| ≥7 | 215 504 (77.1) | 202 141 (72.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 11 (7-17) | 10 (6-15) |

| Total ophthalmologist visitsr | ||

| ≤6 | 274 779 (98.3) | 273 564 (97.7) |

| ≥7 | 4 623 (1.7) | 6580 (2.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) |

| Emergency visitr | ||

| Yes | 82 582 (29.6) | 75 498 (26.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) |

| Hospital admissionr | ||

| Yes | 35 437 (12.7) | 29 574 (10.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) |

| Total drugs dispensedr | ||

| ≤6 | 81 114 (29.0) | 77 936 (27.8) |

| ≥7 | 198 288 (71.0) | 202 208 (72.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (6-14) | 10 (6-15) |

| Physician warning against drivingr,s | 2842 (1.0) | 2937 (1.0) |

| In long-term care facilityt | ||

| Cataract surgery plus anterior vitrectomyu | 1329 (0.5) | 904 (0.3) |

Abbreviations: ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; IQR, interquartile range.

First: April 1, 2006, to March 31, 2011; second; April 1, 2011, to March 31, 2016.

Missing less than 0.0% of data (n = 90 first 5 years; n = 134 for second 5 years).

Missing less than 0.0% of data (n = 897 first 5 years; n = 960 for second 5 years).

More than 1 intravitreal injection in the past 4 years (E149 or E147).

Retinal surgery (E148, E147, E149, E142, E936, E151, E152, E153, or E161), retinal laser (E154), corneal surgery (E121, E951, E122, E124, E123, E206, E205, E207, E937, E948, E117, E118, E119, or E143), or glaucoma/anterior segment surgery (E214, E132, E136, E950, E136, E212, E213, E133, E135, E156, or E157) in the past 4 years.

At least 1 ICD-9 871 918, 921, 930, 940 in past 4 years.

At least 3 visual field tests in the 4 past years (G432).

Time in months from surgeon consultation (A235 or A253) to index date, when available.

At least 2 ICD-9 250 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 401-403 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 491-493 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 311-296 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 297-301 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 428 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 715 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 412 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 244 in the past 4 years.

In the past year.

K035.

Long-term care flag in Ontario Drug Benefit.

Ontario Health Insurance Plan Billing code E940.

Subsequent Traffic Crashes as Drivers

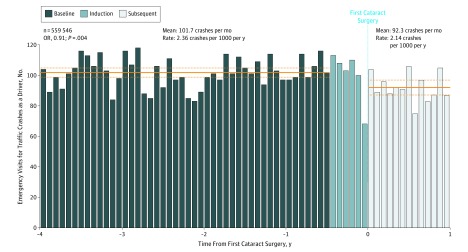

A total of 6482 serious crashes occurred in which the patient was the driver and treated in an emergency department during the baseline, induction, or subsequent months (duration of observation was 5 years for each patient). A total of 4680 crashes occurred during the 46 months of the baseline interval, 602 crashes during the 6 months of the induction interval, and 1200 crashes during the 13 months of the subsequent interval. The mean number of crashes per month was 101.7 in the baseline interval and 92.3 in the subsequent interval (Figure). This equaled a crash rate of 2.36 per 1000 patient-years in the baseline interval and 2.14 per 1000 patient-years in the subsequent interval. The odds ratio (OR) based on GEE analyses comparing the baseline and subsequent interval was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.85-0.97; P = .004). The absolute reduction was 0.22 per 1000 patient-years (mathematically equal to a number needed to treat of 4564 to avoid 1 crash in 1 year).

Figure. Traffic Crashes as a Driver.

The x-axis is divided into 28-day segments. Time 0 defined as the patient’s first cataract surgery. The y-axis shows the rate of emergency department visits for traffic crashes. Induction interval denoted in light blue color is excluded from analysis owing to potential selection bias.

Tests of Robustness

The decreased crash risk in the subsequent interval persisted after stratifying by patient characteristics (Table 2). The reduction was more pronounced among patients older than 75 years, women, those living outside cities, and patients with frequent outpatient visits. The risk reduction was slightly greater during the first 5 years than the second 5 years of the study, although 95% confidence intervals of all subgroups were wide and overlapped the primary analysis. The reduction persisted after excluding patients who received a physician warning (GEE-modeled OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.98; P = .009; n = 553 767) and after excluding patients who did not survive the entire interval (GEE-modeled OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.85-0.97; P = .004; n = 545 318).

Table 2. Subgroup Analyses for Drivers.

| Baseline Characteristic | Total Events | Ratea | Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Subsequent | |||

| Total | 6482 | 2.36 | 2.14 | 0.91 (0.85-0.97) |

| Patient demographics | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| 66-75 | 3460 | 2.52 | 2.38 | 0.95 (0.87-1.04) |

| ≥76 | 3022 | 2.21 | 1.91 | 0.86 (0.78-0.95) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 3376 | 2.93 | 2.76 | 0.94 (0.86-1.03) |

| Female | 3106 | 1.96 | 1.71 | 0.87 (0.79-0.96) |

| Home locationc | ||||

| Urban | 5429 | 2.28 | 2.10 | 0.92 (0.86-0.99) |

| Rural | 1053 | 2.86 | 2.43 | 0.85 (0.72-1.00) |

| Ocular history | ||||

| Time periodd | ||||

| First | 3245 | 2.38 | 2.08 | 0.87 (0.80-0.96) |

| Second | 3237 | 2.35 | 2.21 | 0.94 (0.86-1.03) |

| Wait timee | ||||

| Ambiguous | 2050 | 2.36 | 2.14 | 0.90 (0.81-1.02) |

| Short (≤ 6 mo) | 2498 | 2.25 | 2.03 | 0.90 (0.81-1.00) |

| Long (> 6 mo) | 1934 | 2.53 | 2.32 | 0.92 (0.81-1.03) |

| Medical history | ||||

| Diabetesf | ||||

| Yes | 4640 | 2.29 | 2.09 | 0.91 (0.85-0.99) |

| No | 1842 | 2.58 | 2.29 | 0.89 (0.79-1.01) |

| Hypertensiong | ||||

| Yes | 2953 | 2.46 | 2.16 | 0.88 (0.80-0.97) |

| No | 3529 | 2.29 | 2.13 | 0.93 (0.85-1.02) |

| Total outpatient visitsh | ||||

| ≤6 | 1201 | 1.72 | 1.68 | 0.98 (0.82-1.17) |

| ≥7 | 5281 | 2.58 | 2.30 | 0.89 (0.82-0.97) |

Event rates were calculated per 1000 patient-years during the corresponding interval.

Based on generalized estimating equations model.

Missing less than 0.0% of data (n = 90 first 5 years; n = 134 for second 5 years).

First, April 1, 2006, to March 31, 2011; second, April 1, 2011, to March 31, 2016.

Time in months from surgeon consultation (A235 or A253) to index date, when available.

At least 2 ICD-9 250 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 401-403 in the past 4 years.

In the past year.

Different Subgroups’ Risk of Traffic Crash

Several other patient characteristics were independently associated with a serious traffic crash after cataract surgery (Table 3). The characteristic with the greatest association was a history of a traffic crash in the baseline interval (adjusted OR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.94-4.02) or induction interval (adjusted OR, 4.26; 95% CI, 2.0-9.03). Other associated risk factors on a crude basis included younger patient age (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.09-1.37), male sex (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.44-1.81), emergency visits in the past year (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.29-1.64), more than 6 outpatient physician visits in the past year (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.17-1.56), and 4 specific medical diagnoses; namely, anxiety (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.18-1.54), emphysema (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.06-1.52), osteoarthritis (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.33), and a prior myocardial infarction (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.08-1.45). The same risk factors were also associated after multivariable adjustment except for emphysema and a prior myocardial infarction. Taking into account all patients and stratifying on crash time showed the overall risk reduction was partially explained by daytime driving (total crashes, 5314; GEE-modeled OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.99; P = .02) and partially explained by nighttime driving (total crashes, 1168; GEE-modeled OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.99; P = .04).

Table 3. Risk Factors for a Crash After Cataract Surgery.

| Patient Characteristics | Crash in Subsequent Period, Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | |

| Crash in baseline interval | ||

| Yes vs no | 3.30 (2.29-4.75) | 2.79 (1.94-4.02) |

| Crash in induction interval | ||

| Yes vs no | 5.80 (2.75-12.24) | 4.26 (2.01-9.03) |

| Age, y | ||

| 66-75 vs ≥76 | 1.22 (1.09-1.37) | 1.27 (1.13-1.43) |

| Sex | ||

| Male vs female | 1.61 (1.44-1.81) | 1.64 (1.46-1.85) |

| Home locationb | ||

| Rural vs urban | 1.16 (0.99-1.36) | NA |

| Socioeconomic quintilec | ||

| Lowest vs highest | 1.01 (0.84-1.21) | NA |

| Next to lowest vs highest | 1.02 (0.85-1.22) | NA |

| Middle vs highest | 1.04 (0.87-1.25) | NA |

| Next to highest vs highest | 1.82 (0.86-3.86) | NA |

| Physician warningd,e | ||

| Yes vs no | 0.66 (0.33-1.33) | NA |

| Any hospital admissione | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.06 (0.89-1.27) | NA |

| Any emergency visite | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.46 (1.29-1.64) | 1.34 (1.19-1.52) |

| No. of outpatient visitse | ||

| ≥7 vs ≤6 | 1.36 (1.17-1.56) | 1.17 (1.01-1.36) |

| Diabetesf | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.10 (0.97-1.25) | NA |

| Hypertensiong | ||

| Yes vs no | 0.98 (0.87-1.1) | NA |

| Emphysemah | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.27 (1.06-1.52) | 1.14 (0.96-1.37) |

| Depressioni | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.26 (0.97-1.65) | NA |

| Anxietyj | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.35 (1.18-1.54) | 1.31 (1.14-1.5) |

| Hypothyroidismk | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.14 (0.87-1.49) | NA |

| Osteoarthritisl | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.17 (1.04-1.33) | 1.17 (1.03-1.33) |

| Congestive heart failurem | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.09 (0.88-1.36) | NA |

| Myocardial infarctionn | ||

| Yes vs no | 1.25 (1.08-1.45) | 1.07 (0.92-1.25) |

Abbreviations: ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; NA, not applicable.

From generalized estimated equations model.

Missing less than 0.0% of data (n = 90 first 5 years; n = 134 for second 5 years).

Missing less than 0.0% of data (n = 897 first 5 years; n = 960 for second 5 years).

Ontario Health Insurance Plan billing code K035.

In the past year.

At least 2 ICD-9 250 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 401-403 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 491-493 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 311-296 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 297-301 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 428 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 715 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 412 in the past 4 years.

At least 2 ICD-9 244 in the past 4 years.

Other Major Outcomes

The observed reduction in traffic risks did not extend to control emergencies where the patient was a passenger or pedestrian. The number of crashes where the patient was a passenger equaled 1.59 per 1000 patient-years in the baseline interval and 1.64 per 1000 annually in the subsequent interval (GEE-modeled OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.96-1.12; P = .40). The number of crashes where the patient was a pedestrian equaled 0.49 per 1000 patient-years in the baseline interval and 0.50 per 1000 patient-years in the subsequent interval (GEE-modeled OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.88-1.17; P = .82) (Table 4). Cataract surgery was not associated with a significant reduction in the subsequent risks of other medical events including falls (positive time trend), acute hip fractures (positive time trend), ankle sprains (no time trend), or depression (positive time trend) (Table 4). As expected, cataract surgery was not associated with a significant change in total emergency visits (positive time trend) (Table 4; eFigure in the Supplement).

Table 4. Clinical Outcomes.

| Outcome | Total Events | Ratea | Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Subsequent | |||

| Traffic crashes | ||||

| Driverc | 6482 | 2.36 | 2.14 | 0.91 (0.85-0.97) |

| Passengerd | 4477 | 1.59 | 1.64 | 1.03 (0.96-1.12) |

| Pedestriane | 1351 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 1.02 (0.88-1.17) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Fallf | 127 632 | 41.75 | 58.41 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) |

| Hip fractureg,h | 9039 | 2.80 | 5.19 | 1.04 (0.96-1.12) |

| Ankle spraini | 3828 | 1.36 | 1.33 | 0.98 (0.90-1.06) |

| Depressionh,j | 4521 | 1.59 | 1.72 | 0.94 (0.82-1.07) |

| Overall use | ||||

| Total emergency visitsh,k | 1 490 373 | 496.62 | 655.23 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) |

Abbreviation: ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

Event rates were calculated per 1000 patient-years during the corresponding interval.

Based on generalized estimated equations model with time trend term as appropriate.

ICD-10 codes V1-V6 with appropriate suffixes (driver, motorcyclist, or bicylist).

ICD-10 codes V1-V6 with appropriate suffixes (passenger).

ICD-10 codes V0 (pedestrian).

ICD-10 code W0, W1 (fall).

ICD-10 code s72 (hip fractures).

Statistically significant slope over time. The linear slope variable was incorporated into GEE model, with the resultant OR shown.

ICD-10 codes s394 (ankle sprain).

ICD-10 codes F32-33 (depression).

Any visit to a Ontario emergency department.

Discussion

We studied more than half a million patients who underwent cataract surgery and found a reduction in the patient’s subsequent risk of serious traffic crashes as a driver. The reduction was observed across diverse demographic, ophthalmologic, and medical characteristics. This reduction did not extend to control analyses where the patient was a passenger or a pedestrian nor to health care use as measured by total emergency visits. The overall pattern was not readily explained by aging, other time trends, fluctuating driving patterns, or random chance. The absolute risk reduction corresponds to a number needed to treat with cataract surgery of approximately 5000 to prevent 1 serious traffic crash within 1 year. Together, these results suggest the improvements in visual function from cataract surgery are associated with decreased driving risks.

Other studies have reported larger reductions based on surrogate outcomes such as minor incidents or self-reported performance. A past systematic review and meta-analysis62 (n = 1642 total patients) suggested an overall 88% relative reduction in risk of driving-related difficulties based on self-administered surveys. The effect size obtained in our study was more modest, perhaps because we evaluated serious crashes and did not include crashes where the driver was uninjured, near misses, or self-reported driving difficulties. Bystander injury or collateral property damage were also not quantified. Another distinction may be the study setting because surgeon availability, operating room access, health care funding, cultural differences, and baseline traffic risks by region may influence the association between cataract surgery and traffic crashes. Of note, our observed effect size agreed with a smaller population-based analysis from Australia (n = 15 295).63

Our study also highlights patient groups who are at higher risk for traffic crashes and merit increased attention for road safety warnings. Specifically, patients with a history of a traffic crash were prone to subsequent crashes. The other higher risk characteristics included male sex, younger age, and general comorbidity.64,65 Our findings differ with past reports because we observed an increased risk association with osteoarthritis (for which a speculated mechanism is slowed reaction times or distractions owing to pain).66,67 Regardless of the causal mechanisms, clinicians and policy makers should consider traffic safety risk factors in their decision making and counselling.

Exposure crossover analysis is a powerful self-matching analytic method, yet alternative interpretations and speculation are possible. If patients drove less following cataract surgery, for example, as they age, this change might explain a reduction in traffic crashes. However, our extended baseline showed a stable traffic risks; in contrast, several secondary outcomes showed strong aging trends. Moreover, studies suggest cataract extraction tends to increase subsequent driving including travel in more diverse situations, less familiar routes, and longer distances.28,62 We also found the crash rate in the month immediately after cataract surgery was one of the highest in the subsequent period, perhaps owing to overconfidence, ongoing adaptation, uncorrected refractive error, or anisometropia.68,69,70 Future studies could also explore travel logs, self-reported surveys, or other assessments of driving self-regulation following cataract surgery.54,71,72

Some studies suggest the risk of falls or fractures decreases after cataract surgery, yet 1 study suggests the opposite.63,73 At least at the disease level among operated patients in Ontario, our analysis indicates no large decrease or increase in serious falls or fractures after cataract surgery. Of course, our findings may not be generalizable to previous eras or other regions, do not account for near misses or minor events, and the benefits may diminish as the clinical threshold to perform surgery decreases. These findings further punctuate the reduction seen in traffic crashes.

Our study clarifies why 1 study suggested an increase in falls following cataract surgery. First, a strong time trend means the fall risk increases with age irrespective of cataract surgery. Second, misinterpretation of longitudinal data may suggest a paradoxical increased fracture risk after surgery by mistakenly comparing the immediate preoperative and postoperative interval; that is, selection bias arises because patients are unlikely to have cataract surgery immediately following a serious medical event. Our extended baseline interval and segmentation helps portray these underlying trends and illustrates why a before-and-after analysis can suggest a misleading increase in events after cataract surgery (eFigure in the Supplement).63

Strengths

Strengths of our methods include the matching of stable patient confounders (genetics, personality, habits, and chronic comorbidities), objective outcome event definition (not subject to major selection bias or ascertainment bias), population-wide approach providing inclusiveness, large size, and secondary analyses that explored control events, immortal time bias, statistical artifacts, and selection bias.

Limitations

The largest limitation of our study is that it is not a randomized masked trial testing the effects of cataract surgery. In particular, patients were aware of their diagnosis, mindful of their treatments, and could alter their driving behaviors. Because cognizant drivers attempt to compensate for perceived hazards, the effectiveness of many traffic improvements and safety policies can be attenuated when measured in field studies; visual symptoms could lead to the same offsets (and we were unable to ascertain driving behavior from our database).59,60,61 Therefore, our study indicates a decrease in traffic risks following surgery despite the confounding effects of unmeasured driver compensation and self-regulation before the operation. Our study design also does not allow us to determine factors that might explain the association such as improved visual acuity, better contrast, less glare, or reduced refractive error. Of course, a randomized clinical trial would not address the mechanisms either.

Conclusions

We observed that cataract surgery is associated with a modest decrease in serious traffic crashes. Reducing traffic crashes represents an important objective owing to the significant associated societal costs, morbidity, and mortality.

eFigure. Falls, Hip Fractures, Ankle Sprains, Depression, and Emergency Visits

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Cost of injury: United States: a report to Congress, 1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989;38(43):743-746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safety Research Office, Ministry of Transportation Ontario Road Safety Annual Report 1994. Downsview, Ontario: Safety Research Office, Ministry of Transportation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McFarland RA, Moore RC. Human factors in highway safety; a review and evaluation. N Engl J Med. 1957;256(19):890-897. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195705092561906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li G, Braver ER, Chen LH. Fragility versus excessive crash involvement as determinants of high death rates per vehicle-mile of travel among older drivers. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35(2):227-235. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00107-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owsley C, Stalvey B, Wells J, Sloane ME. Older drivers and cataract: driving habits and crash risk. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(4):M203-M211. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.4.M203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kline DW, Kline TJ, Fozard JL, Kosnik W, Schieber F, Sekuler R. Vision, aging, and driving: the problems of older drivers. J Gerontol. 1992;47(1):27-34. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.1.P27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis LH, Hammill BG, Schulman KA, Cousins SW. Risks of mortality, myocardial infarction, bleeding, and stroke associated with therapies for age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(10):1273-1279. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatch WV, Campbell EdeL, Bell CM, El-Defrawy SR, Campbell RJ. Projecting the growth of cataract surgery during the next 25 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(11):1479-1481. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Defined C. National Eye Institute. https://nei.nih.gov/eyedata/cataract#1. Published 2010. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 11.Bourne RR, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. ; Vision Loss Expert Group . Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e339-e349. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asbell PA, Dualan I, Mindel J, Brocks D, Ahmad M, Epstein S. Age-related cataract. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):599-609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70803-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owsley C, McGwin G Jr. Vision and driving. Vision Res. 2010;50(23):2348-2361. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owsley C, Stalvey BT, Wells J, Sloane ME, McGwin G Jr. Visual risk factors for crash involvement in older drivers with cataract. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(6):881-887. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.6.881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agramunt S, Meuleners LB, Fraser ML, Morlet N, Chow KC, Ng JQ. Bilateral cataract, crash risk, driving performance, and self-regulation practices among older drivers. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(5):788-794. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanthan GL, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, et al. Ten-year incidence of age-related cataract and cataract surgery in an older Australian population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(5):808-814. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cullen KAHM, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory Surgery in the United States, 2006. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellan L. The evolution of cataract surgery: the most common eye procedure in older adults. Geriatr Aging. 2008;11(6):328-332. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riley AF, Grupcheva CN, Malik TY, Craig JP, McGhee CN. The waiting game: natural history of a cataract waiting list in New Zealand. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;29(6):376-380. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2001.d01-25.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leinonen J, Laatikainen L. The decrease of visual acuity in cataract patients waiting for surgery. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77(6):681-684. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laidlaw DA, Harrad RA, Hopper CD, et al. Randomised trial of effectiveness of second eye cataract surgery. Lancet. 1998;352(9132):925-929. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12536-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood J, Chaparro A, Hickson L. Interaction between visual status, driver age and distracters on daytime driving performance. Vision Res. 2009;49(17):2225-2231. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood J, Chaparro A, Carberry T, Chu BS. Effect of simulated visual impairment on nighttime driving performance. Optom Vis Sci. 2010;87(6):379-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood JM, Tyrrell RA, Chaparro A, Marszalek RP, Carberry TP, Chu BS. Even moderate visual impairments degrade drivers’ ability to see pedestrians at night. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(6):2586-2592. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood JM, Carberry TP. Bilateral cataract surgery and driving performance. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(10):1277-1280. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.096057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owsley C, McGwin G Jr, Sloane M, Wells J, Stalvey BT, Gauthreaux S. Impact of cataract surgery on motor vehicle crash involvement by older adults. JAMA. 2002;288(7):841-849. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lotfipour S, Patel BH, Grotsky TA, et al. Comparison of the visual function index to the Snellen Visual Acuity Test in predicting older adult self-restricted driving. Traffic Inj Prev. 2010;11(5):503-507. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2010.488494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keay L, Munoz B, Turano KA, et al. Visual and cognitive deficits predict stopping or restricting driving: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Driving Study (SEEDS). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(1):107-113. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okonkwo OC, Crowe M, Wadley VG, Ball K. Visual attention and self-regulation of driving among older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(1):162-173. doi: 10.1017/S104161020700539X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ontario Ministry of Transportation. Ontario road safety annual report. http://www.mto.gov.on.ca/english/publications/pdfs/ontario-road-safety-annual-report-2011.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 31.Bell CM, Hatch WV, Fischer HD, et al. Association between tamsulosin and serious ophthalmic adverse events in older men following cataract surgery. JAMA. 2009;301(19):1991-1996. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rapoport MJ, Zagorski B, Seitz D, Herrmann N, Molnar F, Redelmeier DA. At-fault motor vehicle crash risk in elderly patients treated with antidepressants. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(12):998-1006. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820d93f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams J, Young W A summary of studies on the quality of health care administrative databases in Canada. https://www.ices.on.ca/flip-publication/patterns-of-health-care-2d-edition/files/assets/common/downloads/ICES%20.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 34.Ontario Population Projections 2008-2036 Ontario and its 49 Census Divisions. http://www.mississauga.ca/file/COM/Ontario_Population_Projections_2008-2036.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 35.Canada S. Focus on Geography Series, 2011 Census Ottawa: Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-pr-eng.cfm?Lang=eng&GC=35. Published 2011. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 36.CIHI Data quality study of emergency department visits for 2004-2005. Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/vol1_nacrs_executive_summary_nov2_2007.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 37.Levy AR, O’Brien BJ, Sellors C, Grootendorst P, Willison D. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10(2):67-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: a validation study. August 19th, 2014. Available from: Available at http://www.ices.on.ca/~/media/Files/Atlases-Reports/2006/CIHI-DAD-a-validation-study/Full%20report.ashx. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 39.Campbell RJ, Bronskill SE, Bell CM, Paterson JM, Whitehead M, Gill SS. Rapid expansion of intravitreal drug injection procedures, 2000 to 2008: a population-based analysis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(3):359-362. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatch WV, Cernat G, Wong D, Devenyi R, Bell CM. Risk factors for acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(3):425-430. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatch WV, Cernat G, Singer S, Bell CM. A 10-year population-based cohort analysis of cataract surgery rates in Ontario. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42(4):552-556. doi: 10.3129/i07-090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell RJ, Gill SS, Bronskill SE, Paterson JM, Whitehead M, Bell CM. Adverse events with intravitreal injection of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):512-516. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, Cauch-Dudek KJ, McAlister FA Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. CORD Conference Proceedings. 2007;1(1):e18-e26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gershon AS, Wang C, Wilton AS, Raut R, To T. Trends in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence, incidence, and mortality in ontario, Canada, 1996 to 2007: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(6):560-565. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Redelmeier DA. The exposure-crossover design is a new method for studying sustained changes in recurrent events. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(9):955-963. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schlenker MB, Thiruchelvam D, Redelmeier DA. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment and the risk of thromboembolism. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(3):569-580.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redelmeier DA, Yarnell CJ, Thiruchelvam D, Tibshirani RJ. Physicians’ warnings for unfit drivers and the risk of trauma from road crashes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(13):1228-1236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1114310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maclure M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133(2):144-153. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Box G, Jenkins G, Reinsel G. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control. Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hodge W, Horsley T, Albiani D, et al. The consequences of waiting for cataract surgery: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2007;176(9):1285-1290. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wait Times for Priority Procedures in Canada https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?pf=PFC2839&lang=fr&media=0. 2015. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 54.Redelmeier DA, Yarnell CJ. Lethal misconceptions: interpretation and bias in studies of traffic deaths. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(5):467-473. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(4):492-499. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vahabzadeh A, McDonald WM, Tibshirani RJ. Physicians’ warnings for unfit drivers and risk of road crashes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):86-87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1212928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12(2):153-157. doi: 10.1007/BF02295996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang M. Generalized estimating equations in longitudinal data analysis: a review and recent developments. Adv Stat. 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/303728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans L. Traffic safety measures, driver behaviour responses, and surprising outcomes. J Traf Med. 1996;24:5-15. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hedlund J. Risky business: safety regulations, risks compensation, and individual behavior. Inj Prev. 2000;6(2):82-90. doi: 10.1136/ip.6.2.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Underwood G, Jiang C, Howarth CI. Modelling of safety measure effects and risk compensation. Accid Anal Prev. 1993;25(3):277-288. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(93)90022-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Subzwari S, Desapriya E, Scime G, Babul S, Jivani K, Pike I. Effectiveness of cataract surgery in reducing driving-related difficulties: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inj Prev. 2008;14(5):324-328. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.017830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meuleners LB, Lee AH, Ng JQ, Morlet N, Fraser ML. First eye cataract surgery and hospitalization from injuries due to a fall: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(9):1730-1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bates LJ, Davey J, Watson B, King MJ, Armstrong K. Factors contributing to crashes among young drivers. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2014;14(3):e297-e305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dischinger PC, Ho SM, Kufera JA. Medical conditions and car crashes. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2000;44:335-346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Margolis KL, Kerani RP, McGovern P, Songer T, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE; Study Of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group . Risk factors for motor vehicle crashes in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(3):M186-M191. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.3.M186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McDonough CM, Jette AM. The contribution of osteoarthritis to functional limitations and disability. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):387-399. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kahneman D, Tversky A. On the psychology of prediction. Psychol Rev. 1973;80:237-251. doi: 10.1037/h0034747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Redelmeier DA, Tibshirani RJ, Evans L. Traffic-law enforcement and risk of death from motor-vehicle crashes: case-crossover study. Lancet. 2003;361(9376):2177-2182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13770-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Horswill MS, Waylen AE, Tofield MI. Drivers’ ratings of different components of their own driving skill: a greater illusion of superiority for skills that relate to accident involvement. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34(1):177-195. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02543.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Janke MKM. Accidents, mileage, and the exaggeration of risk. Accid Anal Prev. 1991;23(2-3):183-188. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(91)90048-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Langford J, Methorst R, Hakamies-Blomqvist L. Older drivers do not have a high crash risk:a replication of low mileage bias. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38(3):574-578. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tseng VL, Yu F, Lum F, Coleman AL. Risk of fractures following cataract surgery in Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2012;308(5):493-501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Falls, Hip Fractures, Ankle Sprains, Depression, and Emergency Visits