Key Points

Question

Is there a hemodynamic contribution from the retinal vasculature in the pathogenesis of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in age-related macular degeneration?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial, eyes with a cilioretinal artery were associated with a lower CNV prevalence, lower age-related macular degeneration severity score, and lower 5-year CNV incidence; but there was no definitive association identified with the prevalence or incidence of geographic atrophy involving the center of the macula.

Meaning

The cilioretinal artery may be protective against the development of CNV; this association suggests a possible hemodynamic contribution to neovascular age-related macular degeneration pathogenesis.

Abstract

Importance

A hemodynamic role in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) has been proposed, but to our knowledge, an association between retinal vasculature and late AMD has not been investigated.

Objective

To determine whether the presence and location of a cilioretinal artery may be associated with the risk of late AMD in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective analysis of prospective, randomized clinical trial data from 3647 AREDS participants. Fundus photographs of AREDS participants were reviewed by 2 masked graders for the presence or absence of a cilioretinal artery and whether any branch extended within 500 μm of the central macula. Multivariate regressions were used to determine the association of the cilioretinal artery and vessel location, adjusted for age, sex, and smoking status, with the prevalence of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) or central geographic atrophy (CGA) and AMD severity score for eyes at randomization and progression at 5 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Association of cilioretinal artery with prevalence and 5-year incidence of CNV or CGA.

Results

Among AREDS participants analyzed, mean (SD) age was 69.0 (5.0) years, with 56.3% female, 46.6% former smokers, and 6.9% current smokers. A total of 26.9% of patients had a cilioretinal artery in 1 eye, and 8.4% had the vessel bilaterally. At randomization, eyes with a cilioretinal artery had a lower prevalence of CNV (5.0% vs 7.6%; OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51-0.85; P = .001) but no difference in CGA (1.1% vs 0.8%; OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.76-2.32; P = .31). In eyes without late AMD, those with a cilioretinal artery also had a lower mean (SD) AMD severity score (3.00 [2.35] vs 3.19 [2.40]; P = .02). At 5 years, eyes at risk with a cilioretinal artery had lower rates of progression to CNV (4.1% vs 5.5%; OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.56-1.00; P = .05) but no difference in developing CGA (2.2% vs 2.7%; OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.56-1.23; P = .35) or change in AMD severity score (0.65 [1.55] vs 0.73 [1.70]; P = .11). In patients with a unilateral cilioretinal artery, eyes with the vessel showed a lower prevalence of CNV than fellow eyes (4.7% vs 7.2%; P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance

The presence of a cilioretinal artery is associated with a lower risk of developing CNV, but not CGA, suggesting a possible retinal hemodynamic contribution to the pathogenesis of neovascular AMD.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00000145

This study examines whether the presence and location of a cilioretinal artery may be associated with the risk of choroidal neovascularization or central geographic atrophy and late age-related macular degeneration in adult participants of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of vision loss in elderly individuals, but its pathophysiology remains largely unknown. The development of early AMD, which is characterized by drusen and pigmentary changes, has been attributed to oxidative stress, lipid accumulation, complement dysregulation, lipofuscin buildup, and choroidal hypoperfusion.1,2,3,4,5,6 Of particular interest are mechanisms contributing to progression to late AMD, including the development of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in neovascular AMD, or retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) loss and outer retinal degeneration in geographic atrophy (GA). Comparisons of postmortem tissues from eyes with CNV and GA have suggested that the primary insult in GA occurs at the RPE, with secondary choriocapillary loss, while CNV appears to result from choriocapillaris degeneration, even in the presence of viable RPE.7,8 Although both CNV and GA may occur at the same time, this evidence suggests a vascular contribution to CNV development, where hemodynamic changes and ischemia drive the release of proangiogenic cytokines such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Perfusion of the neurosensory retina involves oxygen delivery from both the retinal and choroidal circulation. The outer retinal layers are primarily supplied by the choroid. Although the watershed zone between retinal and choroidal circulation normally occurs within the inner nuclear layer, the presence of drusen or Bruch membrane thickening may impair oxygen transport from the choroid, altering the hemodynamic balance between the 2 circulations.9 We hypothesize that the presence of a cilioretinal artery, which is present in approximately 20% of the population and provides ancillary inner retinal circulation to the central macula, could enhance oxygen tension in the macula and protect against the development of CNV. To evaluate this possibility, we analyzed the association between the presence of a cilioretinal artery and the prevalence and incidence of late AMD, including CNV and central GA (CGA), based on fundus photographs from the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS).

Methods

Study Population

The AREDS is a multicenter, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial sponsored by the National Eye Institute to evaluate the use of oral antioxidants for the treatment of AMD. The design and primary results of the study have been extensively reported.10,11 Briefly, 11 clinical centers enrolled 4757 patients aged 55 to 80 years and randomized participants into 1 of 4 treatment conditions: placebo, antioxidants (vitamin C, vitamin E, and β-carotene), zinc only, and antioxidants plus zinc.10 The AREDS protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was conducted prior to the existence of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The AREDS protocol was approved by an independent data and safety monitoring committee and by the institutional review board for each clinical center.12 Enrolled patients were scheduled for follow-up every 6 months for clinical eye examination, visual acuity assessment, and supplement dispensing and adherence assessment.10 Standardized stereoscopic 30° color fundus photography was obtained from each patient annually, and also at nonannual visits if participants had decreased visual acuity.

Fundus Photography and Grading

All AREDS fundus photographs have been previously graded by the University of Wisconsin fundus photograph reading center for the presence, size, type, and area of drusen, the presence of pigmentary abnormalities, CNV, or CGA, and other AMD-related fundus abnormalities.13 These gradings were used to develop the 4-step AREDS classification system for individual patients and the 9-step severity scale for each eye, which reliably predicts 5-year progression risk in patients with AMD.14

For this study, digitized AREDS color fundus photographs and study data were obtained from the National Eye Institute’s Online Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes website (dbGaP accession phs000001, v3.p1.c2) after approval for authorized access. The study was deemed to be exempt by the institutional review board at the University of California, Davis, owing to the use of deidentified fundus photographs and trial data. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment in the AREDS study.12 The original stereoscopic color fundus photographs have been digitized, including macular field 2 (macula) only, to allow for image grading on a computer monitor. Digitalized fundus photographs from each patient were evaluated by 2 independent masked image graders (K.S. and A.M.) to determine the presence or absence of a cilioretinal artery in the macula, defined as a visible retinal vessel arising from the temporal border of the optic disc and extending into the macular region, with no clear association with any branches arising from the central retinal artery.15 We reviewed fundus photographs from the initial qualification visit and graded the cilioretinal artery as present or absent. If the presence of the vessel was questionable, fundus images from subsequent visits were evaluated until the presence or absence of the vessel could be confirmed or left as questionable if the vessel presence could not be clearly ascertained from any available fundus photograph. The cilioretinal artery was also qualitatively evaluated for its location if the vessel path or any of its visible branches traversed within 500 μm of the foveal center, based on the central circle of the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study grid. Any discrepancies between the 2 graders were adjudicated by a senior grader (A.Y. or G.Y.).

Statistical Analyses

A 2-sided P value of .05 was considered to be significant. Information collected from the AREDS data set include the study identification, age, sex, smoking status, as well as the 4-step AREDS category of each patient and 9-step AREDS severity score of each eye, at the baseline randomization visit and the 5-year follow-up visit. The severity score also denotes the presence of CGA, CNV, or both as steps 10, 11, or 12, respectively.14 Differences in clinical characteristics between AREDS participants with a cilioretinal artery in neither, 1, or both eyes were determined using 1-way analysis of variance for scale variables (age), and χ2 tests for categorical variables (sex, smoking status, and AMD category), with post hoc analyses of contingency tables as described by Beasley and Schumacker.16 For individual eyes, multivariate regression analyses using generalized estimating equations were performed to determine the independent association of the presence or location of a cilioretinal artery with the incidence of CNV or CGA (binomial logistic regression), or AMD severity score (linear regression) at randomization, accounting for up to 2 eyes per patient, and adjusted for age, sex, and smoking status. For eyes without either form of late AMD at baseline, we used a similar strategy to compare the risk of developing new CNV or CGA and change in AMD severity score at 5 years in eyes with or without a cilioretinal artery. Finally, in fellow eyes of patients with AMD who have a cilioretinal artery in only 1 eye, we compared the incidence of CNV or CGA using McNemar tests, and AMD severity score at baseline and change at 5 years using paired-samples t tests. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM).

Results

Participant Demographics

Of the 3762 AREDS participants in the online database, 3647 had color fundus photographs in which the cilioretinal artery could be graded (Figure). Among these patients, the mean (SD) age was 69.0 (5.0) years, with more women than men and mostly never and former smokers (Table 1). Of all participants, 26.9% (n = 982) had a cilioretinal artery in one eye, and 8.4% (n = 305) had the vessel in both eyes. There were no significant differences in the mean age, sex, or smoking status among participants with a cilioretinal artery in neither, 1, or both eyes (Table 1). Interestingly, there was a significant difference in the distribution of AREDS category among the 3 groups, with a lower proportion of patients with cilioretinal arteries in the more late AMD categories (Table 1). Post hoc analyses of contingency tables demonstrated a lower proportion of AMD category 1 (22.9% vs 25.2% or 29.5%; P = .03) and higher proportion of AMD category 4 (19.2% vs 16.3% or 15.4%; P = .02) in patients with no cilioretinal artery, and a higher proportion of AMD category 1 in patients with cilioretinal arteries in both eyes (29.5% vs 22.9% or 25.2%; P = .02).

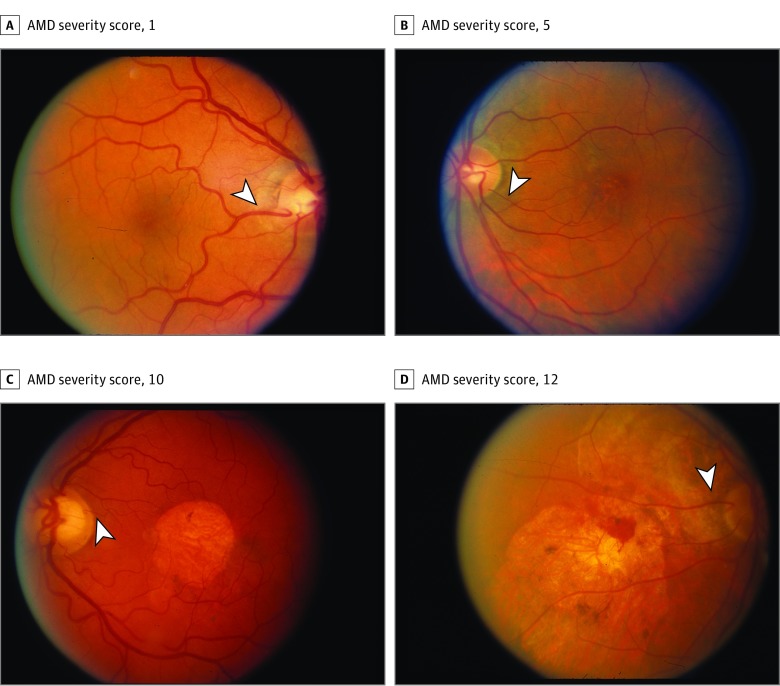

Figure. Fundus Photographs.

Fundus photographs of eyes with cilioretinal arteries and varying age-related macular degeneration (AMD) severity scores in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS). Various examples of cilioretinal arteries (arrowheads) can be seen in eyes with AMD severity score of 1 (A), AMD severity score of 5 (B), AMD severity score of 10 (C; central geographic atrophy), and AMD severity score of 12 (D; choroidal neovascularization and central geographic atrophy).

Table 1. Baseline Demographics of AREDS Participants With and Without Cilioretinal Arteries.

| Demographic | No. (%) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total AREDS Patients With Graded FPs (n = 3647) |

AREDS Patients Without a Cilioretinal Artery (n = 2360) |

AREDS Patients With a Cilioretinal Artery in 1 Eye (n = 982) |

AREDS Patients With a Cilioretinal Artery in Both Eyes (n = 305) |

||

| Age, mean (SD) | 69.0 (5.0) | 69.1 (5.1) | 68.8 (4.9) | 68.9 (4.8) | .31 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1592 | 1026 (43.5) | 423 (43.1) | 143 (46.9) | .48 |

| Female | 2055 | 1334 (56.5) | 559 (56.9) | 162 (53.1) | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 1694 | 1083 (45.9) | 482 (49.1) | 129 (42.3) | .19 |

| Former | 1700 | 1106 (46.9) | 438 (44.6) | 156 (51.1) | |

| Current | 252 | 171 (7.2) | 61 (6.2) | 20 (6.6) | |

| AMD category | |||||

| 1 | 878 | 541 (22.9) | 247 (25.2) | 90 (29.5) | .03 |

| 2 | 808 | 504 (21.4) | 234 (23.8) | 70 (23.0) | |

| 3 | 1302 | 863 (36.6) | 341 (34.7) | 98 (32.1) | |

| 4 | 659 | 452 (19.2) | 160 (16.3) | 47 (15.4) | |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; AREDS, Age-Related Eye Disease Study; FP, fundus photograph.

Association of Cilioretinal Artery With AMD Status at Baseline

Because we hypothesized that the protective effect of a cilioretinal retinal artery is specific to the eye, rather than individual patients, we analyzed AMD severity at baseline in eyes with or without a cilioretinal artery. We reviewed 48 864 macular field (field 2) fundus photographs from 7252 individual eyes, of which 5 eyes were determined to be ungradeable from fundus photographs of any visits. Of the 7247 eyes, 6966 eyes had AMD severity score available at randomization (eFigure in the Supplement), of which 1531 eyes (22.0%) had a cilioretinal artery and 1180 eyes (16.9%) showed a cilioretinal artery that visibly traversed the central macula. The prevalence of CNV was significantly lower in eyes with a cilioretinal artery (5.0% vs 7.6%; OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51-0.85; P = .001), while the prevalence of CGA was similar in both groups (1.1% vs 0.8%; OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.76-2.32; P = .31), even after adjustment for age, sex, and smoking status (Table 2; eTable 1 in the Supplement). The proportion of eyes with neither form of late AMD was also significantly higher in eyes with a cilioretinal artery (94.1% vs 91.7%; OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.11-1.77; P = .004) (Table 2). Whether the cilioretinal artery visibly traversed the central macula showed no difference in the prevalence of CNV (4.8% vs 5.6%; P = .37) or CGA (0.9% vs 1.8%; P = .18). In the 6424 eyes without late AMD at randomization, the mean (SD) AMD severity score was also lower in those with a cilioretinal artery than those without (3.00 [2.35] vs 3.19 [2.40]; OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02) (Table 2; eTable 2 in the Supplement). These data suggest that the presence of a cilioretinal artery is associated with a less severe AMD phenotype, with a lower prevalence of CNV, but not CGA.

Table 2. Baseline AMD Status in AREDS Eyes With and Without a Cilioretinal Artery.

| Status | No. (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Eyes (n = 6966) |

Cilioretinal Artery Absent (n = 5435) |

Cilioretinal Artery Present (n = 1531) |

|||

| AMD status | |||||

| No late AMD | 6424 (92.2) | 4894 (91.7) | 1440 (94.1) | 1.40 (1.11-1.77) | .004 |

| CNV | 489 (7.0) | 412 (7.6) | 77 (5.0) | 0.66 (0.51-0.85) | .001 |

| CGA | 63 (0.9) | 46 (0.8) | 17 (1.1) | 1.33 (0.76-2.32) | .31 |

|

Eyes at Risk (n = 6424) |

Cilioretinal Artery Absent (n = 4984) |

Cilioreretinal Artery Present (n = 1440) |

|||

| AMD severity score, mean (SD) | 3.15 (2.39) | 3.19 (2.40) | 3.00 (2.35) | 0.84 (0.73-0.97) | .02 |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; AREDS, Age-Related Eye Disease Study; CGA, central geographic atrophy; CNV, choroidal neovascularization; OR, odds ratio.

Based on multivariate binomial logistic regression (AMD status) or linear regression (AMD severity score) using generalized estimating equations, accounting for both eyes per patient, and adjusted for age, sex, and smoking status.

Association of Cilioretinal Artery With AMD Progression at 5 Years

At the 5-year follow-up, 6319 of 6424 eyes without late AMD at baseline and at risk of progression had AMD severity scores available for analysis (eFigure in the Supplement). Among these eyes at risk with no late AMD at baseline, 327 (5.2%) developed CNV and 162 (2.6%) developed CGA (Table 3). Eyes with a cilioretinal artery showed a lower rate of progression to CNV (4.1% vs 5.5%; OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.56-1.00; P = .05) but not CGA (2.2% vs 2.7%; OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.56-1.23; P = .35), and a greater proportion of eyes that did not develop any form of late AMD (93.8% vs 92.1%; OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.00-1.64; P = .05) (Table 3; eTable 1 in the Supplement). Again, the proximity of the cilioretinal artery to the central macula did not affect the rate of CNV development (4.1% vs 4.2%; P = .18). The mean (SD) change in AMD severity score was not significantly different between eyes with and without a cilioretinal artery (0.65 [1.55] vs 0.73 [1.70]; P = .11) (Table 3; eTable 2 in the Supplement). Hence, while the presence of a cilioretinal artery also appears to reduce progression to CNV over 5 years, there was no clear effect on the nonneovascular aspects of the disease.

Table 3. 5-Year AMD Progression in AREDS Eyes With and Without a Cilioretinal Artery.

| Status | No. (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyes at Risk (n = 6319) |

Cilioretinal Artery Absent (n = 4901) |

Cilioretinal Artery Present (n = 1418) |

|||

| AMD status | |||||

| No late AMD | 5843 (92.5) | 4513 (92.1) | 1330 (93.8) | 0.75 (0.56-1.00) | .05 |

| CNV | 327 (5.2) | 269 (5.5) | 58 (4.1) | 0.83 (0.56-1.23) | .35 |

| CGA | 162 (2.6) | 131 (2.7) | 31 (2.2) | 1.28 (1.00-1.64) | .05 |

| Change in AMD severity score, mean (SD) | 0.71 (1.67) | 0.73 (1.70) | 0.65 (1.55) | 0.93 (0.84-1.02) | .11 |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; AREDS, Age-Related Eye Disease Study; CGA, central geographic atrophy; CNV, choroidal neovascularization; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Based on multivariate binomial logistic regression (AMD status) or linear regression (AMD severity score) using generalized estimating equations, accounting for both eyes per patient, and adjusted for age, sex, and smoking status.

Fellow-Eye Comparisons in Participants With a Unilateral Cilioretinal Artery

To better isolate the association of a cilioretinal artery with AMD development and exclude the potential associations with genetic or environmental factors that may influence disease progression, we analyzed the subset of AREDS participants who had a cilioretinal artery in only 1 eye. Of 932 patients with a unilateral cilioretinal artery, the eye with the vessel demonstrated a much lower prevalence of CNV than the fellow eye (4.7% vs 7.2%; P = .01) and a lower mean (SD) AMD severity score (3.41 [2.89] vs 3.67 [2.35]; P = .004), but no difference in CGA (1.0% vs 0.9%; P > .99) at randomization (Table 4). In the 791 AREDS participants who had a unilateral cilioretinal artery, neither eye had late AMD at baseline and an AMD severity score documented for both eyes at 5 years; however, we found no clear difference in rates of CNV development (1.9% vs 2.5%; P = .44), CGA (1.8% vs 2.3%; P = .42) or change in AMD severity score (1.35% vs 1.50%; P = .18) (Table 4). Nevertheless, while the association may not be detectable in this smaller subset of patients at 5 years, the presence of a cilioretinal artery appears to be protective against CNV and not GA in the larger baseline cohort.

Table 4. AMD Status and Progression in AREDS Participants With a Cilioretinal Artery in Only 1 Eye.

| Status | No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eye With Cilioretinal Artery (n = 932) |

Fellow Eye Without Cilioretinal Artery (n = 932) |

||

| Prevalence of late AMD at baseline | |||

| AMD status | |||

| No late AMD | 882 (94.6) | 852 (91.4) | .01 |

| CNV | 44 (4.7) | 72 (7.2) | .01 |

| CGA | 9 (1.0) | 8 (0.9) | >.99 |

| AMD severity score, mean (SD) | 3.41 (2.89) | 3.67 (2.35) | .004 |

|

Eye at Risk With Cilioretinal Artery (n = 791) |

Fellow Eye at Risk Without Cilioreretinal Artery (n = 791) |

||

| Progression to late AMD at 5 y | |||

| AMD status | |||

| No late AMD | 763 (96.5) | 754 (95.3) | .19 |

| CNV | 15 (1.9) | 20 (2.5) | .44 |

| CGA | 14 (1.8) | 18 (2.3) | .45 |

| Change in AMD severity score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.51 (1.35) | 0.59 (1.50) | .18 |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; AREDS, age-related eye disease study; CGA, central geographic atrophy; CNV, choroidal neovascularization; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Despite the wide prevalence of AMD, little is known about the mechanisms that trigger progression from drusen in early-intermediate AMD, to CNV, or CGA in late AMD. A vascular role in the pathogenesis of AMD has been postulated previously.17 Friedman6 hypothesized that increased scleral rigidity owing to atherosclerosis increases resistance to blood flow and impairs choroidal venous drainage, resulting in RPE dysfunction and lipoprotein accumulation. Age-related macular degeneration has been linked to hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and stroke in large-scale clinical studies.18,19,20 Progression to neovascular AMD involves proangiogenic factors such as VEGF induced by hypoxia and ischemia. Reduced choroidal blood flow and choriocapillaris dropout have also been documented in both early and late AMD.7,8 Although some experts argue that choriocapillaris loss may be secondary to outer retinal degeneration, several lines of evidence suggest that changes in the choroidal microvasculature may be the incipient event, particularly in neovascular AMD.7

While the choroid’s role in AMD continues to be debated, even less is known about the association between the retinal vasculature and AMD. In a small case-control study published more than 20 years ago, the presence of a cilioretinal artery was noted to be lower in a small cohort of eyes with CNV compared with patients with central serous chorioretinopathy.21 A cilioretinal artery was also associated with less subretinal fluid in patients with neovascular AMD.22 In our study, we used the large, publicly available data set of AREDS fundus photograph and found (1) a lower proportion of late AMD categories among AREDS participants with at least 1 ciliorertinal artery, (2) a lower prevalence and 5-year incidence of CNV in eyes with a cilioretinal artery, and (3) lower rates of CNV in the eye with the vessel compared with fellow eyes in patients with a unilateral cilioretinal artery. This consistent association from different approaches, particularly in the subgroup analysis of fellow eyes, provides a replication of results, and further strengthens the conclusions of our study. We noted that the lower CNV prevalence and AMD severity score at baseline were more pronounced than differences in CNV incidence and AMD severity score change at 5 years, possibly because the protective effect occurs over a long period and because fewer patients had adequate follow-up compared with the cohort at randomization. In fact, we also investigated whether the protective effect of the cilioretinal artery would be more pronounced among the subgroup of patients with AMD category 3 or 4 at baseline who are at higher risk for developing late AMD. In this subanalysis of 3736 eyes, we found that CNV prevalence at randomization was similarly lower in eyes with a cilioretinal artery (10.1% vs 13.9%; OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55-0.91; P = .007) but that the lower 5-year CNV incidence among the 3133 eyes at risk did not reach statistical significance (8.5% vs 10.7%; OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.57-1.06; P = .11). Our study also cannot account for potential interactions with oral antioxidants in the AREDS study because the treatments were systemic and the possible influence of a cilioretinal artery is specific to the eye. Nevertheless, our results suggest a protective effect of a cilioretinal artery against CNV but not CGA and supports a contributing role of the retinal circulation to the development of neovascular AMD.

Cilioretinal arteries belong to the posterior ciliary arterial system, usually arising from the peripapillary choroid or directly from 1 of the short posterior ciliary arteries. The prevalence of cilioretinal arteries has been reported in up to 40% of normal eyes, depending on detection method.23,24,25 In our cohort of eyes with AMD, we found only 22.0% (n = 1531) of graded eyes had a cilioretinal artery. In addition, only 26.9% of AREDS patients (n = 982) had a cilioretinal artery in 1 eye and 8.4% (n = 305) had the vessel in both eyes, compared with a bilateral occurrence rate of 14.6% to 17% of normal individuals reported in literature,23,26 hence providing further support for a protective effect from the cilioretinal artery.

In contrast to the retinal vasculature, the choroid provides most of the oxygen delivered to the retina, using high blood flow and a steep gradient of oxygen tension to overcome the RPE/Bruch membrane barrier.27 Although the watershed zone lies within the inner nuclear layer, soft drusen or Bruch membrane thickening in AMD may impair oxygen supply from the choroid, disrupting the hemodynamic balance between retinal and choroidal circulation.21,28 We speculate that the retinal circulation may partly compensate for this impairment and that the cilioretinal artery could enhance perfusion of the central macula and protect against the development of CNV.

Limitations

Studies by Hayreh showed that the area supplied by cilioretinal arteries vary widely,23 with some supplying the entire retina24,25,26 and even ones that lack a central retinal artery completely.27 We attempted to determine whether the anatomic proximity of the cilioretinal artery to the central macula showed a greater protective effect but did not find a difference. We suspect that the area perfused by a cilioretinal artery is broader than the visible vessel course, so that our study is partly limited by the use of fundus photography alone for identifying the cilioretinal artery. In contrast, fluorescein angiography is more sensitive, can more accurately distinguish these vessels from intraneural branches of the central retinal artery, and can map the perfusion area of cilioretinal arteries. Also, the AREDS definitions of late AMD do not account for noncentral GA, which warrant further investigation for their relationship with the retinal vasculature. Future studies that use a more robust analysis of retinal vasculature, possibly with the use of optical coherence tomography angiography, may circumvent some limitations of our analysis.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, our study is the largest evaluation of cilioretinal arteries in patients with AMD to date and showed a lower prevalence of CNV and lower AMD severity in eyes with a cilioretinal artery. While this association does not indicate causality, these findings shed some light on the vascular contribution to AMD pathogenesis and warrants further investigation into the role of the retinal circulation in the development of neovascular AMD.

eTable 1. Clinical Factors Associated With Neovascular AMD at baseline and at 5 Years, Including Presence of a Cilioretinal Artery

eTable 2. Clinical Factors Associated With AMD Severity Score at baseline and at 5 years, Including Presence of a Cilioretinal Artery

eFigure. Flow Chart Demonstrating Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) Subject Data Analyzed

References

- 1.Curcio CA, Johnson M, Rudolf M, Huang JD. The oil spill in ageing Bruch membrane. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(12):1638-1645. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mettu PS, Wielgus AR, Ong SS, Cousins SW. Retinal pigment epithelium response to oxidant injury in the pathogenesis of early age-related macular degeneration. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33(4):376-398. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sparrow JR, Duncker T. Fundus autofluorescence and RPE lipofuscin in age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Med. 2014;3(4):1302-1321. doi: 10.3390/jcm3041302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson DH, Radeke MJ, Gallo NB, et al. The pivotal role of the complement system in aging and age-related macular degeneration: hypothesis re-visited. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(2):95-112. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn P, Qian Y, Dentchev T, et al. Disruption of ceruloplasmin and hephaestin in mice causes retinal iron overload and retinal degeneration with features of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(38):13850-13855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405146101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman E. A hemodynamic model of the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(5):677-682. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)70906-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLeod DS, Grebe R, Bhutto I, Merges C, Baba T, Lutty GA. Relationship between RPE and choriocapillaris in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(10):4982-4991. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullins RF, Johnson MN, Faidley EA, Skeie JM, Huang J. Choriocapillaris vascular dropout related to density of drusen in human eyes with early age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(3):1606-1612. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhutto I, Lutty G. Understanding age-related macular degeneration (AMD): relationships between the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch’s membrane/choriocapillaris complex. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33(4):295-317. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS): design implications: AREDS report no. 1. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20(6):573-600. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(99)00031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report No. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1417-1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randomized A; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group . A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report No. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1417-1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group The Age-Related Eye Disease Study system for classifying age-related macular degeneration from stereoscopic color fundus photographs: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study Report Number 6. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(5):668-681. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(01)01218-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis MD, Gangnon RE, Lee LY, et al. ; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group . The Age-Related Eye Disease Study severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 17. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(11):1484-1498. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.11.1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorentzen SE. Incidence of cilioretinal arteries. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1970;48(3):518-524. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1970.tb03753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beasley TM, Schumacker RE. Multiple regression appraoch to analyzing contingency tables: post hoc and planned comparison procedures. J Exp Educ. 1995;64(1):79-93. doi: 10.1080/00220973.1995.9943797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutty G, Grunwald J, Majji AB, Uyama M, Yoneya S. Changes in choriocapillaris and retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 1999;5:35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong TY, Klein R, Sun C, et al. ; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study . Age-related macular degeneration and risk for stroke. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(2):98-106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-2-200607180-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan Y, Mo J, Klein R, et al. Age-related macular degeneration is associated with incident myocardial infarction among elderly Americans. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(4):732-737. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyman L, Schachat AP, He Q, Leske MC; Age-Related Macular Degeneration Risk Factors Study Group . Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(3):351-358. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.3.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winther-Tham C, Lindblom B. Presence of cilioretinal arteries in eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1994;72(3):397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebraheem A, Uji A, Abdelfattah NS, Nittala MG, Sadda S, Le PV. Relationship between the presence of a cilioretinal artery and subretinal fluid in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;2(5):469-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayreh SS. The cilioretinal arteries In: Hayreh SS, ed. Ocular Vascular Occlusive Disorders. Basel, Switzerland: Springer; 2014:55-64. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayreh SS. Acute retinal arterial occlusive disorders. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30(5):359-394. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegde V, Deokule S, Matthews T. A case of a cilioretinal artery supplying the entire retina. Clin Anat. 2006;19(7):645-647. doi: 10.1002/ca.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsa CF, Cheeseman EW Jr, Maumenee IH. Demonstration of exclusive cilioretinal vascular system supplying the retina in man: vacant discs. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1998;96:95-106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salzmann M. The Anatomy and Histology of the Human Eyeball in the Normal State: Its Development and Senescence. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1912. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim LA, Li D, McHugh KJ, Kwark L, Farsiu S, Saint-Geniez M A model of retinal oxygenation to predict conversion to neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Paper presented at: American Society of Retinal Specialists Annual Meeting; 2017; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Clinical Factors Associated With Neovascular AMD at baseline and at 5 Years, Including Presence of a Cilioretinal Artery

eTable 2. Clinical Factors Associated With AMD Severity Score at baseline and at 5 years, Including Presence of a Cilioretinal Artery

eFigure. Flow Chart Demonstrating Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) Subject Data Analyzed