Abstract

This study uses US community cohort data to assess BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing among medically underserved Medicare beneficiaries with breast cancer, ovarian cancer, or both.

Identifying pathogenic germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes can affect therapeutic and preventive recommendations for individuals with cancer. It is unclear whether medically underserved individuals are afforded the option to test for such mutations. We assessed BRCA1 and BRCA2 test uptake in a cohort of medically underserved Medicare beneficiaries with breast cancer, ovarian cancer, or both.

Methods

The analytic cohort was drawn from the Southern Community Cohort Study, a prospective study of 84 513 participants (66% black, 30% white) recruited in 2002-2009 from community health centers across 12 states in the southeastern United States1 (federally funded clinics serving areas and populations that lack access to primary care). Half of the cohort was covered by Medicare (80% in fee-for-service).

Women diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer while enrolled in Medicare Part B were identified through linkage with state cancer registries and Medicare claims from 2000 to 2014. Eligibility for Medicare coverage of BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing, based on family history and patient or tumor characteristics, was determined using cancer registry data, pathology reports, and family history. Medical records were reviewed for the frequency of genetic services referrals. Medicare Part B claims were used to ascertain BRCA1 and BRCA2 test receipt, as described in Lynch et al2: (1) those with a BRCA1- and BRCA2-specific Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition, code (81162, 81211-81217) or, before 2013, (2) those with methodology-based codes (83891, 83898, 83904, 83909, 83912) paid to Myriad laboratories (the only clinical laboratory in the United States at the time offering BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing), with a diagnostic code of breast or ovarian cancer or family history of these cancers.3 Because Medicare criteria for BRCA1 and BRCA2 test coverage broadened in December 2006 (per national recommendations4), we divided participants into 2 periods based on diagnosis date (March 2000-November 2006 and December 2006-June 2014) before assessing eligibility.

Temporal trends in test rate were assessed by the Cochran-Armitage test. A 2-sided P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using Stata (StataCorp), version 14.0. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Vanderbilt University; written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Results

Of 49 642 female cohort study participants, 2002 were diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer from 2000 to 2014; 751 were covered by Medicare Part B at diagnosis. After excluding women who died before 6 months postdiagnosis (n = 33), the final cohort consisted of 718 women (62% black and 33% white). Mean age was 64.0 years (SD, 9.1) at breast cancer diagnosis (n = 689) and 62.5 years (SD, 9.5) at ovarian cancer diagnosis (n = 30). Annual income of less than $15 000 was reported by 62% of women; 30% had less than a high school education.

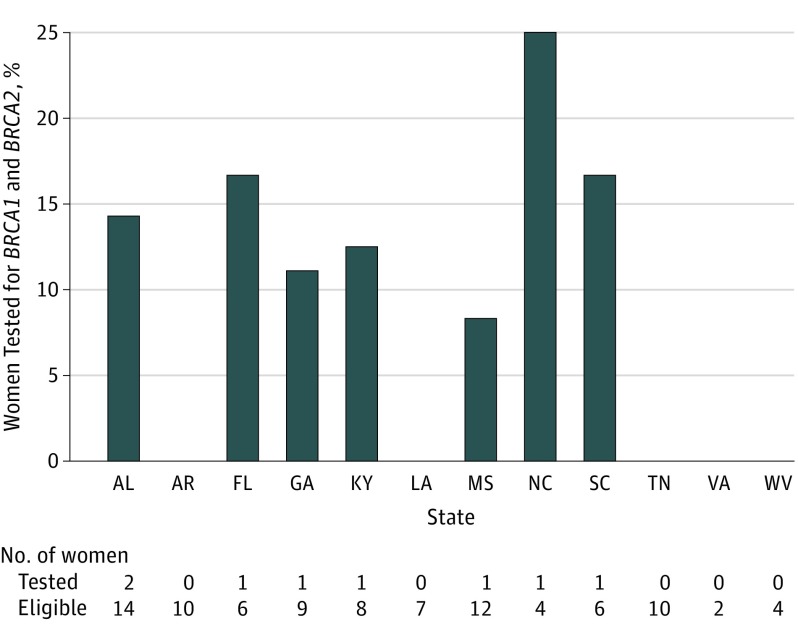

Medicare criteria for BRCA1 and BRCA2 test coverage was met by 92 women (12.8%); only 8 (8.7%) were tested over a median follow-up time of 4.9 years (interquartile range [IQR], 2.5-7.7) postdiagnosis. Median time between diagnosis and test claim date was 117 days (IQR, 34-415). Test rates increased over time, from 0 of 14 women (0%) in 2000-2004, to 2 of 40 women (5% [95% CI, 0.6%-17.0%]) in 2005-2009, to 6 of 38 women (15.8% [95% CI, 6.0%-31.3%]) in 2010-2014 (P for trend = .04). No state exceeded a test rate of 25%; 5 states had a test rate of 0 (Figure). Medical record review for 48 of 92 eligible women revealed that less than 10% of treating physicians documented a need for genetic services; none recorded referral to genetic counseling.

Figure. BRCA1 and BRCA2 Testing Rates Among Eligible Women by State.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on BRCA1 and BRCA2 test rates in a cohort of medically underserved women with breast or ovarian cancer. Test uptake was low among eligible women residing in the southeastern United States, less than the rate of 52.9% reported in a study of test-eligible women with breast cancer (2013-2014) from Georgia and Los Angeles County.5

The low test rate observed could be due to several factors, including lack of patient interest, physician recommendation, or resources. Limitations include lack of complete medical records for all test-eligible women, potential inaccuracy of medical records, small sample size, and no data on second-degree cancer family history, likely leading to underestimates of eligibility. Novel strategies are needed to ensure that medically underserved women with cancer receive appropriate referral and access to genetic testing.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. The Southern Community Cohort Study: investigating health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1)(suppl):26-37. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch J, Berse B. Methods to identify BRCA testing in claims data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):133-134. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization The ICD-10: classification of mental and behavioural disorders. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/bluebook.pdf?ua=1. Accessed June 25, 2018.

- 4.Daly MB, Pilarski R, Berry M, et al. . NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian: version 2: 2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:9-20. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurian AW, Griffith KA, Hamilton AS, et al. . Genetic testing and counseling among patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. JAMA. 2017;317(5):531-534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]