Abstract

This study uses Medicare part B billing data to compare trends in the use of filgrastim and its biosimilars among beneficiaries between 2014 and 2016.

Biologic pharmaceuticals are complex, high-cost therapeutics used to treat severe and chronic conditions.1 Biosimilar biological products can increase access to therapy and lower health care costs. The development and approval of biosimilar biologics in the United States was made possible by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act passed in 2010. As of June 1, 2018, 10 biosimilars had been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).2 This study evaluated uptake of the first approved biosimilar biologic, filgrastim-sndz (Zarxio), relative to its originator filgrastim product (Neupogen). These products share multiple indications for neutropenia and malignancy. Tbo-filgrastim (Granix), a stand-alone alternative biologic with a single indication, was also evaluated.

Methods

All filgrastim administrations of any dose between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2016, in Medicare Part B claims were identified using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System billing codes. Beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare fee for service from at least 6 months before to at least 10 days after administration. Cohorts were defined by the filgrastim product administered; beneficiaries were included in multiple cohorts if they received multiple products during the study period. Beneficiary demographics and prevalence of indicated conditions were evaluated. This descriptive study was approved as an FDA surveillance activity by the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research institutional review board liaison. Least squares regression was used to depict the utilization trend. A standardized mean difference threshold of 0.1 was used to highlight larger differences between cohort characteristics. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

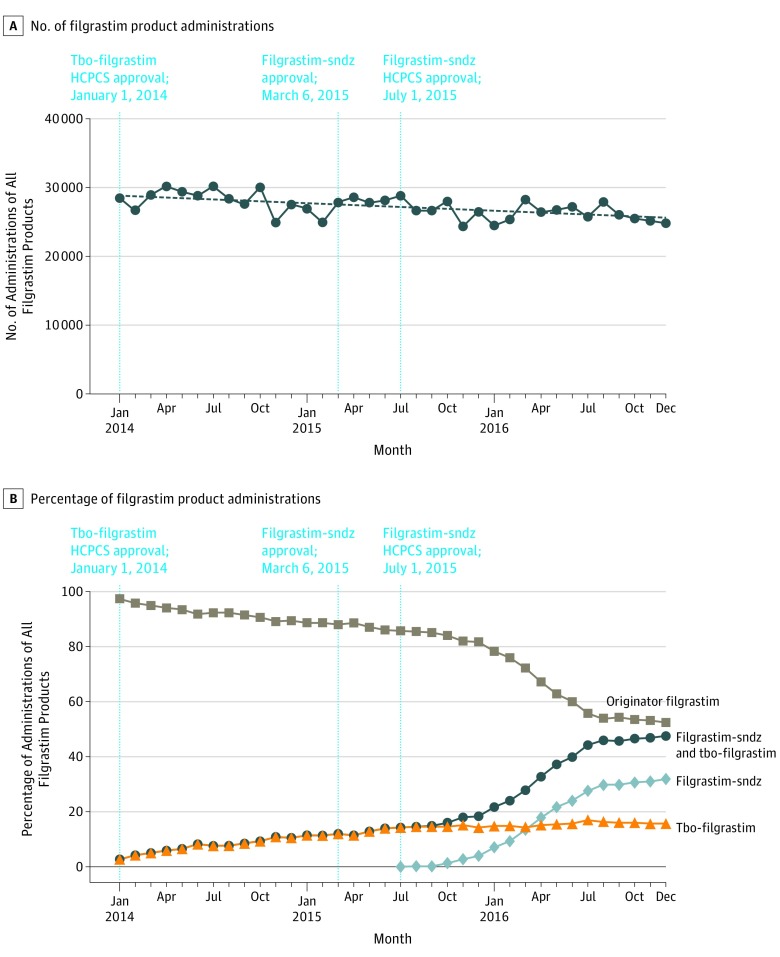

Monthly administrations of any filgrastim product decreased by 13%, from 28 520 in January 2014 to 24 898 in December 2016 (Figure, A). Monthly administrations of filgrastim-sndz increased to 32% of all filgrastim use and tbo-filgrastim increased to 16%, while the originator filgrastim product declined from 97% to 52% (Figure, B). Initial uptake of filgrastim-sndz was rapid, with monthly use surpassing tbo-filgrastim in March 2016.

Figure. Trends in All Filgrastim Administrations.

The figure summarizes the number (A) and percentage (B) of administration of all filgrastim products (filgrastim [originator], filgrastim-sndz, and tbo-filgrastim) for each month during the study period from the study start to study end dates (January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016). Given that the use of filgrastim and alternative filgrastim products cannot be observed in the Medicare data until the approval of a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code, the study start date was restricted to the tbo-filgrastim HCPCS approval date (January 2014) rather than the drug approval date (August 2012). Therefore, tbo-filgrastim use between the drug approval date and the HCPCS approval date is not included in this study. To capture all filgrastim administrations through late 2016, the Medicare data were evaluated in September 2017. The red and blue broken lines indicate the US FDA and HCPCS code approval dates for tbo-filgrastim and filgrastim-sndz, respectively.

Beneficiaries who received filgrastim-sndz were on average slightly older. Product choice also differed by geographic region and original Medicare enrollment status (Table). Among beneficiaries who received filgrastim-sndz, 22% had previously received the originator filgrastim and 73% were new users.

Table. Demographic Characteristics of Filgrastim Usersa.

| Characteristics | No. (%) | Maximum SMDb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filgrastim (originator) | Tbo-filgrastim | Filgrastim-sndz | ||

| No. of eligible beneficiaries | 86 040 | 19 083 | 9955 | |

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 71.0 (9.8) | 70.6 (10.1) | 72.0 (8.9) | 0.16c |

| <65 | 11 830 (14) | 3019 (16) | 1098 (11) | 0.14c |

| 65-74 | 44 009 (51) | 9675 (51) | 5096 (51) | 0.01 |

| 75-84 | 25 077 (29) | 5291 (28) | 3071 (31) | 0.07 |

| ≥85 | 5124 (6) | 1098 (6) | 690 (7) | 0.05 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 39 497 (46) | 8622 (45) | 4428 (44) | 0.03 |

| Female | 46 543 (54) | 10 461 (55) | 5527 (56) | 0.03 |

| Raced | ||||

| White | 72 421 (84) | 16 063 (84) | 8538 (86) | 0.04 |

| Black | 8052 (9) | 1735 (9) | 779 (8) | 0.05 |

| Other | 5567 (6) | 1285 (7) | 638 (6) | 0.01 |

| Census regione | ||||

| West | 15 640 (18) | 4567 (24) | 2187 (22) | 0.14c |

| Midwest | 18 395 (21) | 4725 (25) | 2122 (21) | 0.08 |

| South | 35 763 (42) | 6036 (32) | 4409 (44) | 0.26c |

| Northeast | 15 907 (18) | 3742 (20) | 1234 (12) | 0.20c |

| Unknown/other | 335 (<1) | 13 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 0.08 |

| Original Medicare statusf | ||||

| Aged (without ESRD) | 66 602 (77) | 14 129 (74) | 7984 (80) | 0.15c |

| Disabled (without ESRD) | 17 057 (20) | 4158 (22) | 1832 (18) | 0.08 |

| ESRD | 2381 (3) | 796 (4) | 139 (1) | 0.17c |

| Dual Medicare/Medicaid status | ||||

| Dual eligible | 13 319 (15) | 3260 (17) | 1406 (14) | 0.08 |

| Not dual eligible | 72 721 (85) | 15 823 (83) | 8549 (86) | 0.08 |

| Associated filgrastim indicationsg | ||||

| Nonmyeloid malignancy and chemotherapy | 61 863 (72) | 13 315 (70) | 7278 (73) | 0.07 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia and chemotherapy | 838 (1) | 204 (1) | 106 (1) | 0.01 |

| Nonmyeloid malignancy, chemotherapy, and bone marrow transplantation | 42 (<1) | 16 (<1) | 4 (<1) | 0.02 |

| Bone marrow harvest | 1940 (2) | 282 (1) | 111 (1) | 0.09 |

| Neutropenia | 7357 (9) | 2303 (12) | 1063 (11) | 0.12c |

| No labeled indication observed | 14 000 (16) | 2963 (16) | 1393 (14) | 0.06 |

| Previous filgrastim use | ||||

| None | 84 059 (98) | 14 470 (76) | 7274 (73) | 0.74c |

| Filgrastim originator | 4305 (23) | 2217 (22) | 0.01 | |

| Tbo-filgrastim | 1475 (2) | 277 (3) | 0.07 | |

| Filgrastim-sndz | 479 (1) | 242 (1) | 0.07 | |

| Multiple filgrastim types | 27 (<1) | 66 (<1) | 187 (2) | 0.19c |

Beneficiaries were included if they (1) received a filgrastim injection between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2016; (2) were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A/B fee for service from 6 months prior to administration through 10 days after administration, and (3) did not receive the cohort-defining drug for 6 months prior to filgrastim administration. The first of each type of filgrastim administration satisfying these requirements was selected as the beneficiary’s index administration. These eligibility requirements allow beneficiaries to enter multiple filgrastim product cohorts.

The standardized mean difference (SMD) standardizes comparisons by describing differences in means using units of the pooled standard deviation. A threshold of 0.1 was used to identify larger differences. Only the largest SMDs comparing differences across filgrastim product groups are reported.

SMD >0.1.

Race information is taken from the beneficiary race code variable in the Medicare Beneficiary Summary file.

Region is defined by the US Census Bureau’s census regions.

Beneficiaries can enter Medicare because of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), age (≥65 years), or disability.

Identification of each filgrastim indication was based on the best available definition using Medicare claims data; medical record confirmation for presence of each indication was not included in the study scope.

The prevalence of indications was similar across all products despite tbo-filgrastim’s single indication for patients with nonmyeloid malignancies receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. This indication was associated with 70% to 73% of claims across all products.

Discussion

Substantial uptake of alternative filgrastim products occurred in 2014-2016, including among beneficiaries previously receiving the originator product. The more rapid uptake of filgrastim-sndz over the stand-alone biologic does not appear to be driven by the products’ list prices, as the tbo-filgrastim discount from the originator product was similar to or higher than3 the initial discount of 15% for filgrastim-sndz.4 The use of tbo-filgrastim beyond its labeled indication may result from clinicians’ familiarity with product use outside the US approval system, accepted practices, product availability, or other factors. Although biosimilar uptake rates in the United States mirror the experience of some European Union countries,5 the decline in filgrastim use differs from the increase in the United Kingdom.6 Although this study looked at filgrastim administrations billed only through Medicare Part B, a small percentage of overall filgrastim claims are billed through Part D instead. Additionally, presence of indications was identified with claims data definitions; no medical record confirmation was available. Data on filgrastim utilization can inform future research and policy as the number of approved biosimilar products increases.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Megerlin F, Lopert R, Taymor K, Trouvin JH. Biosimilars and the European experience: implications for the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1803-1810. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research list of licensed biological products. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/UCM560162.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 3.Royzman I. United States: the value of being highly similar: first US biosimilar. http://www.mondaq.com/unitedstates/x/391742/food+drugs+law/The+Value+of+Being+Highly+Similar+First+US+Biosimilar. Accessed February 18, 2018.

- 4.FDANews Sandoz launches Zarxio at 15 percent lower price than Neupogen. https://www.fdanews.com/articles/173036-sandoz-launches-zarxio-at-15-percent-lower-price-than-neupogen. Accessed February 18, 2018.

- 5.Grabowski H, Guha R, Salgado M. Biosimilar competition: lessons from Europe. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(2):99-100. doi: 10.1038/nrd4210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics Delivering on the Potential of Biosimilar Medicines: The Role of Functioning Competitive Markets March 2016. https://www.medicinesforeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMS-Institute-Biosimilar-Report-March-2016-FINAL.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2018.