Key Points

Question

Are anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens, and pazopanib active in advanced epithelioid sarcoma (ES)?

Finding

This multi-institutional case series included 115 patients with advanced ES treated with anthracycline-based regimens (85), gemcitabine-based regimens (41), or pazopanib (18) between 1990 and 2016 at 17 sarcoma centers in Europe, the United States, and Japan. The response rate and the median progression-free survival (PFS) in the anthracycline-group were 22% and 6 months; 27% and 4 months in the gemcitabine-group; 0 and 3 months with pazopanib.

Meaning

Anthracycline-based and gemcitabine-based regimens are moderately active in advanced ES, with similar response rates and PFS, whereas the activity of pazopanib seemed limited.

This observational study examines the activity of anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens, and pazopanib in patients with advanced epithelioid sarcoma.

Abstract

Importance

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is an exceedingly rare malignant neoplasm with distinctive pathologic, molecular, and clinical features as well as the potential to respond to new targeted drugs. Little is known on the activity of anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens, and pazopanib in this disease.

Objective

To report on the activity of anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens, and pazopanib in patients with advanced ES.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Seventeen sarcoma reference centers in Europe, the United States, and Japan contributed data to this retrospective analysis of patients with locally advanced/metastatic ES diagnosed between 1990 and 2016. Local pathological review was performed in all cases to confirm diagnosis according to most recent criteria.

Exposures

All patients included in the study received anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens, or pazopanib.

Main Outcome and Measures

Response was assessed by RECIST. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were computed by Kaplan-Meier method. Classic and proximal subtypes were defined based on morphology (according to 2013 World Health Organization guidelines).

Results

Overall, 115 patients were included, 80 (70%) were men and 35 (30%) were women, with a median age of 32 years (range, 15-77 years). Of the 115 patients with ES, 85 were treated with anthracycline-based regimens, 41 with gemcitabine-based regimens, and 18 with pazopanib. Twenty-four received more than 1 treatment. Median follow-up was 34 months. Response rate for anthracycline-based regimens was 22%, with a median PFS of 6 months. One complete response (CR) was reported. A trend toward a higher response rate was noticed in morphological proximal type (26%) vs classic type (19%) and in proximal vs distal primary site (26% vs 18%). The response rate for gemcitabine-based regimens was 27%, with 2 CR and a median PFS of 4 months. In this group, a trend toward a higher response rate was reported in classic vs proximal morphological type (30% vs 22%) and in distal vs proximal primary site (40% vs 14%). In the pazopanib group, no objective responses were seen, and median PFS was 3 months.

Conclusions and Relevance

This is the largest retrospective series of systemic therapy in ES. We confirm a moderate activity of anthracycline-based and gemcitabine-based regimens in ES, with a similar response rate and PFS in both groups. The value of pazopanib was low. These data may serve as a benchmark for trials of novel agents in ES.

Introduction

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a rare sarcoma subtype, with an incidence rate of 0.02 per 100 000 and 0.05 per 100 000 in Europe and the United States, respectively.1 World Health Organization classification distinguishes 2 morphological variants of ES: the classic type and the proximal type, both predominantly integrase interactor 1 (INI1) deficient.2,3,4

The prognosis in ES is serious, especially for proximal type, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 50%.1 In metastatic patients, the reported median survival is approximately 12 months.5,6,7,8,9

The current knowledge on the activity of commonly used drugs for sarcoma in ES is based on limited retrospective studies.8,10,11,12,13 This is particularly relevant today, when new target agents potentially active in this disease are under evaluation.14

The aim of this international, collaborative study, including 17 referral sarcoma centers in Europe, the United States, and Japan participating in the World Sarcoma Network effort, was to report on the activity of anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens, and pazopanib in adult patients with advanced ES.

Methods

Population

We considered all patients with locally advanced/metastatic ES, diagnosed between January 1990 and June 2016, treated with anthracycline-based, gemcitabine-based regimens, or pazopanib. Patients treated with adjuvant/neoadjuvant intent were excluded. Approval by the institutional review board of each institution was obtained, and written informed consent was obtained as required by local regulation.

Study Design

Data were extracted from clinical databases. The diagnosis and morphological subtype were reviewed and confirmed by each institutional sarcoma pathologist. Treatment response was assessed according to RECIST 1.1.15

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize population characteristics. Comparisons between response rates were made using Fisher exact tests.

Progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were estimated by using Kaplan-Meier method, distributions by group were compared through log-rank tests. Progression-free survival was calculated from the treatment start to the first documented evidence of progressive disease (PD), death owing to any cause, or last follow-up. Patients undergoing surgery after medical treatments were censored at the time of PD after surgical resection or at the last follow-up. Overall survival was calculated from the treatment start to the time of death from any cause or the last follow-up. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out with SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc) and R statistical software (version 3.4.0, R Foundation).

Results

Population

One-hundred-fifteen patients with locally advanced/metastatic ES treated with an anthracycline-based regimen, gemcitabine-based regimen, or pazopanib were identified. Among them, 80 (70%) were men and 35 (30%) were women. The median age in the population was 32 years (range, 15-77 years). The median follow-up was 34 months (interquartile range [IQR], 22-210 months). The median OS was 17.8 (IQR, 9.5-33.1) months. Integrase interactor 1 was deficient in all evaluable cases. The Table summarizes patient characteristics.

Table. Population Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracycline-Based | Gemcitabine-Based | Pazopanib | |

| No. of patients | 85 | 41 | 18 |

| INI-1 IHC statusa | |||

| Deficient | 59 (69) | 31 (76) | 17 (94) |

| Unavailable | 26 (31) | 10 (24) | 1 (6) |

| Age, median (range), y | 32 (15-77) | 34 (15-76) | 31 (15-67) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 61 (72) | 26 (63) | 13 (72) |

| Female | 24 (28) | 15 (37) | 5 (28) |

| Primary siteb | |||

| Distal | 34 (40) | 20 (49) | 10 (56) |

| Proximal | 51 (60) | 21 (51) | 8 (44) |

| Histological type | |||

| Classic | 43 (51) | 23 (56) | 11 (61) |

| Proximal | 42 (49) | 18 (44) | 7 (39) |

| Stage | |||

| Locally advanced | 14 (17) | 1 (2) | 3 (16.7) |

| Locoregional lymphnodal involvement | 15 (18) | 7 (17) | 2 (11.1) |

| Metastatic | 56 (66) | 33 (81) | 13 (72.2) |

Abbreviations: IHC, immunohistochemistry; INI-1, integrase interactor 1.

By immunohistochemical analysis.

Distal primary sites: hand, forearm, foot. Proximal primary sites: head, neck, trunk, arm, axilla, thigh, groin, buttock, urogenitalia.

Treatment Response and Outcome

Eighty-five, 41, and 18 patients were included in the anthracycline group, gemcitabine group, and pazopanib group, respectively. Twenty-four patients received more than 1 of the selected treatments. eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement report treatment details.

Anthracycline-Based Regimens

Best RECIST response for anthracycline-based regimens was 1 complete response (CR, 1%), 18 (21%) partial response (PR), 45 (53%) stable disease (SD), and 21 (25%) PD. The response rate was 22%.

The median PFS was 6 (IQR, 2.3-10.4) months. The median PFS in responding patients was 9 months (IQR, 4.6-20.6), 7 in proximal type (IQR, 3-21), and 9 in classic type ES (IQR, 7-not evaluable [NE]). The median PFS in nonresponding patients was 5 months (IQR, 2.2-9.2), 4 in proximal type (IQR, 2-9), and 5 in classic type ES (IQR, 3-10). The median OS (all lines of therapy considered together) was 16 months (IQR, 8.4-28.6).

Gemcitabine-Based Regimens

Best RECIST response for gemcitabine-based regimens was 2 (5%) CR, 9 (22%) PR, 16 (39%) SD, and 14 (34%) PD. The response rate was 27%.

The median PFS was 4 (IQR, 2.0-11.9) months. The median PFS in responding patients was 16 months (IQR, 7.1-NE), 20 in proximal type (IQR, 13-NE), and 10 in classic type ES (IQR, 7-NE). The median PFS in nonresponding patients was 3 months (IQR, 1.7-6.2), 3 in both proximal type and classic type. The median OS was 19 months (IQR, 8.9-37.3).

Pazopanib

Best RECIST response with pazopanib was 9 (50%) SD and 9 (50%) PD. Two prolonged SD were observed (27 and 21 months). The median PFS and OS were 3 (IQR, 2.1-11.2) and 14 (IQR, 5-33.1) months, respectively.

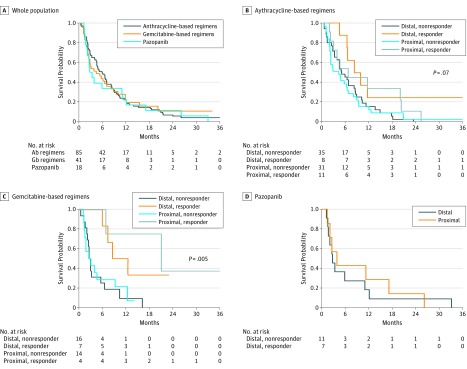

eTable 3 in the Supplement reports response rate, median PFS, and median OS by subtype, primary site, and response to treatment. eTable 4 in the Supplement reports population outcome. The Figure shows Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS.

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Curves .

Abbreviations: Ab, anthracycline based; Gb, gemcitabine based. A, Kaplan-Meier curves for overall progression-free survival by treatment group. B, Progression-free survival according to treatment response and morphologic subtype in advanced epithelioid sarcoma patients treated with anthracycline-based regimens (n = 85); C, gemcitabine-based regimens (n = 41); and D, pazopanib (n = 18).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this international retrospective study collected the largest series currently available of patients with advanced ES treated with systemic therapy. One hundred fifteen patients were included. Anthracycline-based regimens (response rate, 22%) and gemcitabine-based regimens (response rate, 27%) are active in a proportion of patients with ES. A trend toward a higher response rate to anthracycline-based regimens was noticed in pathologic proximal type compared with classic type ES, and in patients with anatomically proximal tumor sites. However, duration of response was low, particularly in proximal type ES. In the gemcitabine-based treatment group, the response rate was slightly higher in patients with morphological classic type ES and distal primary sites. No responses were seen with pazopanib and PFS was low.

Given the rarity of ES, collaborative retrospective efforts are of major relevance to provide clinical guidance. With all the limitations of a retrospective study, our case series is the largest available on the activity of systemic therapies for patients with ES. Updated follow-up was available for more than 90% of patients, though with some limitations (since the date of last radiological assessment was unknown in some cases, patients were censored at the time of the last follow-up). Pathologic diagnosis was confirmed by a dedicated sarcoma pathologist and INI1 status was known in most cases.

In our series anthracycline-based regimens were associated with an response rate of 22% and a 6-month median PFS. Of 3 published retrospective studies, results are conflicting about tumor response rate to anthracycline (ranging from 0 to 43%) and PFS (3 to 8 months).8,10,13 In our series, we observed responses both in classic type (19%) and in proximal type (26%). However, the median PFS in responding patients was low (9 months), particularly for proximal type ES. Our data might therefore encourage the use of anthracyclines in the proximal type, especially if some integration with surgery is foreseen.

With gemcitabine-based regimens, we observed an response rate of 27% and a median PFS of 4 months, confirming what was previously reported by Pink et al10 (response rate, 58%; PFS, 8 months). The responses observed by Pink and colleagues were similar in both subtypes, whereas in our study gemcitabine-based regimens appeared slightly more active in classic type ES (30% vs 22%) and distal primary site. A favorable PFS was observed in responding patients of both subtypes, especially in the proximal type subgroup. In distal type ES the natural history of disease may be a confounding factor.

The activity of pazopanib in our study was limited. Notably, pazopanib was mainly used in further line and in a limited number of patients. A long-lasting PR in a proximal type ES (INI1 undetermined) treated in first-line has been reported.11 Although we cannot exclude the activity of pazopanib in some cases, it seems inferior to anthracycline-based and gemcitabine-based regimens.

Conclusions

Although the number of patients was low, we observed signs of a differential activity of anthracycline-based and gemcitabine-based regimens between the 2 ES variants. Unfortunately, we were not able to further break down distal ES according to their more or less aggressive morphologic appearance, in a disease regarded today as high-grade by definition. Indeed, a degree of heterogeneity can be observed upfront and across relapses. A further subtype-adapted grading system based on pathologic features and its correlation with treatment response would be interesting to explore. We also hope that this report will provide a benchmark for future trials on medical agents in this disease.

eTable 1. Treatment details

eTable 2. Regimens used and corresponding response rate

eTable 3. Response rate, median progression-free survival, and median overall survival by morphological subtype, primary site, and response to treatment

eTable 4. Population outcome

References

- 1.Frezza AM, Botta L, Pasquali S, et al. An epidemiological insight into epithelioid sarcoma (ES): the open issue of distal-type (DES) versus proximal type (PES). Presented at the European Society of Medical Oncology Annual Meeting, Madrid, Spain, September, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher CDMBJ, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(4):-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenca M, Rossi S, Lorenzetto E, et al. . SMARCB1/INI1 genetic inactivation is responsible for tumorigenic properties of epithelioid sarcoma cell line VAESBJ. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(6):1060-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. . Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French sarcoma group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131(2):222-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, Umeda T, Yokoyama R, Hirohashi S. Proximal type epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(7):655-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asano N, Yoshida A, Ogura K, et al. . Prognostic value of relevant clinicopathologic variables in epithelioid sarcoma: a multi-institutional retrospective study of 44 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(8):2624-2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones RL, Constantinidou A, Olmos D, et al. . Role of palliative chemotherapy in advanced epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35(4):351-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jawad MU, Extein J, Min ES, Scully SP. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with epithelioid sarcoma: 441 cases from the SEER database. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(11):2939-2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pink D, Richter S, Gerdes S, et al. . Gemcitabine and docetaxel for epithelioid sarcoma: results from a retrospective, multi-institutional analysis. Oncology. 2014;87(2):95-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irimura S, Nishimoto K, Kikuta K, et al. . Successful Treatment with Pazopanib for Multiple Lung Metastases of Inguinal Epithelioid Sarcoma: A Case Report. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8(3):378-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tlemsani C, Dumont S, Ropert S, et al. Vinorelbine-based chemotherapy in metastatic epithelioid sarcoma. Presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Chicago, June, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casanova M, Ferrari A, Collini P, et al. ; Italian Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee . Epithelioid sarcoma in children and adolescents: a report from the Italian Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee. Cancer. 2006;106(3):708-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gounder MM, Stacchiotti S, Schöffski P, et al. Phase 2 multicenter study of the EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat in adults with INI1 negative epithelioid sarcoma (NCT02601950). Presented at ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. . New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Treatment details

eTable 2. Regimens used and corresponding response rate

eTable 3. Response rate, median progression-free survival, and median overall survival by morphological subtype, primary site, and response to treatment

eTable 4. Population outcome