Abstract

This cohort study investigates overall survival among patients with newly diagnosed metastatic cervical cancer who received chemotherapy alone compared with those who received chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy.

Definitive pelvic chemoradiation is the standard of care for locally advanced cervical cancer.1 However, the role of definitive local radiation therapy for metastatic cervical cancer has not been established. In addition, there is growing evidence that local therapies may be associated with an increase in survival among patients with some types of metastatic cancers.2,3,4,5 In this study, we evaluated overall survival among patients with metastatic cervical cancer treated with chemotherapy alone vs pelvic chemoradiation.

Methods

The National Cancer Database was used to identify patients with newly diagnosed metastatic cervical cancer who received chemotherapy with and without radiation therapy. Patients who received no treatment or treatment with radiation therapy alone, who underwent surgery, or who had missing baseline variables were excluded. Patients who received pelvic external beam radiationtherapy with or without brachytherapy were considered in the chemoradiation therapy group. Overall survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, log-rank test, Cox proportional hazards models, landmark analysis, and propensity score–matched analyses using variables including radiation, age, year of diagnosis, race, comorbidity score, grade, clinical tumor stage and nodal stage, facility type, insurance, and metastatic site (distant lymph node, distant organ, or both). Overall survival was further analyzed by radiation dose (total dose, ≥45 Gy vs <45 Gy) and by radiation type (external beam radiation therapy plus brachytherapy vs external beam radiation therapy alone). Subgroup survival analyses were done by age, comorbidity score, clinical tumor stage and nodal stage, and metastatic site. All statistical analyses were done using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), with a 2-sided P ≤ .05 considered as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed in January 2018. Studies involving the National Cancer Database have been classified as not human subjects research by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, and therefore this study was exempt from institutional review board review. All patients were deidentified in this study.

Results

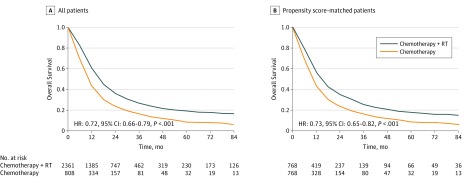

From 2004 to 2014, among 3169 patients with metastatic cervical cancer (mean [SD] age, 53.6 [12.9] years; age range, 19-90 years), 808 received chemotherapy alone and 2361 received pelvic chemoradiation. At a median follow-up of 13.3 months (range, 0.1-151 months), having received chemoradiation was associated with improved survival on univariate analysis (hazard ratio [HR], 0.65 [95% CI, 0.60-0.71]; P < .001) and multivariate analysis (HR, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.66-0.79]; P < .001) compared with having received chemotherapy alone (Figure and Table). Propensity score-matched analysis demonstrated superior median survival (14.4 [95% CI, 12.8-15.7] vs 10.6 [95% CI, 9.7-11.3] months; P < .001) among patients receiving chemoradiation. Median survival was significantly longer among patients who received therapeutic radiation therapy with a dose greater than or equal to 45 Gy (18.5 [95% CI, 17.4-19.9] vs 10.2 [95% CI, 9.4-11.5] months) and external beam radiation therapy plus brachytherapy (27.5 [95% CI, 24.5-31.3] vs 12.9 [95% CI, 12.2-13.8] months) than it was among those who received palliative radiation therapy (doses <45 Gy) and external beam radiation therapy alone (all P < .001). On subgroup analyses, chemoradiation was associated with better survival than chemotherapy alone for all subgroups, including those with distant node–only metastasis (HR, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.54-0.77]; P < .001), organ-only metastasis (HR, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.61-0.82]; P < .001), and both nodal and organ metastasis (HR, 0.83 [95% CI, 0.70-0.98]; P = .02).

Figure. Overall Survival Among Patients With Metastatic Cervical Cancer Who Received Chemotherapy With or Without Pelvic Radiation.

Comparison of overall survival among patients who received chemotherapy and radiation therapy (RT) vs patients who received chemotherapy alone among all patients (n = 3169) (A) and among propensity score–matched patients (n = 1536) (B).

Table. Survival Analysis for All Patients and Propensity Score-Matched Patients.

| Treatment | No. of Patients | Median Survival (95% CI), mo | 2-y OS, % | Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariable | ||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI)a | P Value | ||||

| All patients | 3169 | ||||||

| Chemotherapy alone | 808 | 10.1 (9.1-10.9) | 23 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Pelvic RT Plus Chemotherapy | 2361 | 15.6 (15.0-16.5) | 36 | 0.65 (0.60-0.71) | <.001 | 0.72 (0.66-0.79) | <.001 |

| EBRT<45 Gy Plus Chemotherapy | 681 | 10.2 (9.4-11.5) | 22 | 0.95 (0.85-1.06) | .33 | 0.95 (0.84-1.06) | .32 |

| EBRT≥45 Gy Plus Chemotherapy | 1501 | 18.5 (17.4-19.9) | 42 | 0.56 (0.50-0.61) | <.001 | 0.63 (0.57-0.70) | <.001 |

| EBRT/BT Plus Chemotherapy | 670 | 27.5 (24.5-31.3) | 55 | 0.40 (0.35-0.45) | <.001 | 0.50 (0.44-0.57) | <.001 |

| EBRT alone Plus Chemotherapy | 1691 | 12.9 (12.2-13.8) | 29 | 0.79 (0.72-0.87) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.73-0.89) | <.001 |

| Concurrent CRT | 1781 | 16.4 (15.2-17.8) | 38 | 0.63 (0.57-0.69) | <.001 | 0.70 (0.63-0.79) | <.001 |

| Nonconcurrent CRTb | 580 | 14.3 (13.1-15.4) | 30 | 0.72 (0.64-0.81) | <.001 | 0.76 (0.69-0.83) | <.001 |

| Propensity-matched patientsc | 1536 | ||||||

| Chemotherapy alone | 768 | 10.6 (9.7-11.3) | 24 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Pelvic RT Plus Chemotherapy | 768 | 14.4 (12.8-15.7) | 35 | 0.72 (0.64-0.80) | <.001 | 0.73 (0.65-0.82) | <.001 |

| EBRT<45 Gy Plus Chemotherapy | 257 | 9.0 (7.5-11.0) | 24 | 1.05 (0.88-1.25) | .55 | 1.01 (0.85-1.21) | .87 |

| EBRT≥45 Gy Plus Chemotherapy | 461 | 17.6 (15.7-20.7) | 40 | 0.61 (0.53-0.68) | <.001 | 0.63 (0.55-0.72) | <.001 |

| EBRT/BT Plus Chemotherapy | 183 | 30.0 (21.6-36.9) | 55 | 0.42 (0.34-0.50) | <.001 | 0.50 (0.41-0.61) | <.001 |

| EBRT alone Plus Chemotheapy | 585 | 12.2 (11.3-13.7) | 29 | 0.86 (0.76-0.97) | .01 | 0.83 (0.73-0.93) | .002 |

Abbreviations: BT, brachytherapy; CRT, chemoradiation; EBRT, external beam radiation; HR, hazard ratio; NCDB, National Cancer Database; OS, overall survival; RT, radiation therapy.

Multivariate HRs are adjusted for the same factors analyzed in the primary analysis, as described in the Methods.

Sequential chemoradiation could not be defined because the time of last chemotherapy is not available in the NCDB.

Propensity analysis was done by 1-to-1 nearest-neighbor matching, and the caliper width was 0.05 times the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score.

Discussion

Radiation therapy and surgery were included in the 2017 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline for metastatic cervical cancer despite limited clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of these therapies. We identified 176 patients who received hysterectomy with chemotherapy, and they had significantly longer survival than did patients who received chemotherapy alone (median survival, 23.2 [95% CI, 18.3-27.9] vs 10.1 [95% CI, 9.1-10.9] months; P < .001), which supports that definitive local therapies (radiation therapy and surgery) may benefit patients with metastatic cervical cancer. To our knowledge, this analysis represents the largest reported cohort of patients with metastatic cervical cancer who received local therapies.

To account for potential selection biases between responder and nonresponder (ie, immortal time bias), we performed sequential landmark analysis, which demonstrated significant improvement in survival among long-term survivors at 1 or more, 2 or more, and 3 or more years (all P < .05). This finding suggests that the benefit of pelvic radiation therapy in the study was not attributable to immortal time bias.6 In addition, by using the time of treatment (chemotherapy or radiation therapy) initiation, we found that 75% of patients (1781 of 2361) who received chemoradiation received concurrent chemoradiation and that they had slightly better survival than did patients who received nonconcurrent chemoradiation (Table), which helped to rule out the selection bias that radiation therapy was selectively delivered to patients who received chemotherapy first and had good response. This study has several limitations. The information for specific chemotherapy agents, salvage therapies, performance status, and disease-specific survival is not available in the National Cancer Database. Despite these limitations, the results in this analysis are intriguing.

Conclusions

Newly diagnosed metastatic cervical cancer managed with definitive pelvic radiation therapy and chemotherapy was associated with substantially longer survival than treatment with chemotherapy alone. Prospective trials evaluating definitive local radiation therapy for metastatic cervical cancer are warranted.

References

- 1.Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, et al. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1137-1143. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ning MS, Ahobila V, Jhingran A, et al. Outcomes and patterns of relapse after definitive radiation therapy for oligometastatic cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148(1):132-138. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ioffe YJ, Massad LS, Powell MA, et al. Survival of cervical cancer patients presenting with occult supraclavicular metastases detected by FDG-positron emission tomography/CT: impact of disease extent and treatment. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2018;83(1):83-89. doi: 10.1159/000458706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rusthoven CG, Jones BL, Flaig TW, et al. Improved survival with prostate radiation in addition to androgen deprivation therapy for men with newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2835-2842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez DR, Blumenschein GR Jr, Lee JJ, et al. Local consolidative therapy versus maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer without progression after first-line systemic therapy: a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1672-1682. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30532-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson JR, Cain KC, Gelber RD. Analysis of survival by tumor response. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1(11):710-719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.11.710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]