Key Points

Question

What clinical and laboratory markers are associated with relapse of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa?

Findings

In this case series of 21 patients with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, 4 of 10 patients in the relapse group had pretreatment cutaneous ulcers compared with none of the 11 in the nonrelapse group. Compared with the nonrelapse group, patients with relapse had elevated serum C-reactive protein levels, absolute neutrophil counts, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios, and elevated systemic immune-inflammation indices.

Meaning

In pretreatment status, these laboratory factors may be associated with relapse in cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa.

Abstract

Importance

In cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (CPAN), less aggressive treatments can be selected, because CPAN is not associated with life-threatening or progressive outcomes. Although patients with a recurrent clinical course may require additional immunosuppressive therapies, no pretreatment factors associated with a worse prognosis in CPAN have been reported.

Objective

To identify clinical or laboratory markers associated with relapse of CPAN.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective case series was performed at a dermatology clinic of a tertiary referral center in Okayama, Japan, from October 1, 2001, through April 30, 2017. Of 30 patients identified with CPAN, the 21 with histopathologic evidence of disease were eligible and enrolled in the study.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The medical database was examined for sex, age at diagnosis, affected anatomical sites, type and extent of skin lesion, laboratory data, initial therapies, duration of follow-up, and current status. Relapse was defined as the first reoccurrence or new onset of cutaneous disease that required further escalation of treatment with prednisolone at a dosage of greater than 20 mg/d and/or add-on use of immunosuppressant therapy, more than 6 months after initial treatment. The pretreatment factors were statistically evaluated between the groups without and with relapse.

Results

The 21 patients included 5 males and 16 females with a median age of 49 years (range, 11-74 years) at diagnosis. The median follow-up was 42 months (range, 8-374 months). Pretreatment cutaneous ulcer was significantly associated with relapse between the 2 groups (0 of 11 in the nonrelapse group vs 4 of 10 in the relapse group; χ21 = 4.67; P < .05). In the laboratory test results, significantly higher mean (SD) values were observed in the relapse group for C-reactive protein level (0.23 [2.00] vs 6.03 [3.10] mg/dL; standard error of the mean [SEM], 3.40 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.01-10.8 mg/dL; P = .01), absolute neutrophil count (ANC) (3.4 × 103/μL [1.1 × 103/μL] vs 6.0 × 103/μL [3.2 × 103/μL]; SEM, 2.9 × 103/μL; 95% CI, 1.9 × 103/μL to 14.6 × 103/μL; P = .001), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (1.4 [0.8] vs 2.8 [0.9]; SEM, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-4.9; P = .002), and systemic immune-inflammation index (5.1 × 105 [3.9 × 105] vs 11.7 × 105 [7.7 × 105]; SEM, 7.3 × 105; 95% CI, 3.3 × 105 to 31.1 × 105; P = .007). The estimated 2-year cumulative relapse rate was significantly high in the patients with blood ANC of greater than 4.9 × 103/μL compared with 4.9 × 103/μL or less (9 of 10 [90%] vs 2 of 11 [18%]; 95% CI, 6%-72%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Pretreatment status of cutaneous ulcer, the serum C-reactive protein level, the blood ANC, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and the systemic immune-inflammation index are associated with a worse prognosis in CPAN.

This case series identifies clinical and laboratory markers that may be associated with relapse among patients with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa.

Introduction

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (CPAN) is a rare form of necrotizing vasculitis involving small and medium arteries that affects skin preferentially.1,2,3,4 Based on the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference of 2012 on the classification of the vasculitides, CPAN has been reclassified as cutaneous arteritis in single-organ vasculitis.5 The clinical course of CPAN is usually not life-threatening or progressive. Occasionally, extracutaneous symptoms such as malaise, arthralgia, and neuropathy may occur.3,6

Patients with CPAN and a recurrent clinical course may require additional immunosuppressive therapy after initial treatment. Prognostic markers of CPAN relapse have been undetermined. We conducted the present retrospective analysis to investigate and identify such potential markers.

Methods

Patients

Thirty patients with CPAN who were treated at Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan, from October 1, 2001, through April 30, 2017, were examined. Histopathologic diagnosis consisted of necrotizing vasculitis involving small and medium arteries in the deep dermal to subcutaneous fat of the affected skin. To rule out systemic disease, we checked laboratory findings, including levels of antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and complement. Computed tomography, visceral angiography, and endoscopy of the gastrointestinal tract were also examined, when indicated. Of the 30 patients, 21 were eligible for the study and enrolled (Table 1). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Okayama University Hospital, and all patients provided written informed consent for their data to be used, in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1. List of Clinical Features and Initial Therapies of 21 Japanese Patients.

| Patient No./Sex/Decade of Age at Onset | Cutaneous Manifestation | Localization | Neuropathy | Arthropathy | Initial Therapy | Follow-up, mo | Current Status/Therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Leg | Thigh | Trunk | Arm | Head/Neck | |||||||

| 1/M/50s | Indurated erythema; livedo; cutaneous ulcer; purpura | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | Prednisone, 30 mg/d | 374 | Death due to brain hemorrhage |

| 2/M/30s | Indurated erythema; livedo; cutaneous ulcer; purpura | + | + | + | + | + | − | +a | Ticlopidine hydrochloride, cilostazol, and aspirin | 335 | Prednisone, 5 mg/d, and warfarin |

| 3/F/20s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | Prednisone, 45 mg/d | 296 | PSL4 |

| 4/F/10s | Indurated erythema | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | Intravenous pulse methylprednisolone and prednisone, 45 mg/d | 243 | Complete response |

| 5/F/60s | Indurated erythema; livedo; purpura | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | Prednisone, 50 mg/d | 49 | Death due to infection |

| 6/F/30s | Indurated erythema | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | NSAIDs | 31 | Complete response |

| 7/F/50s | Indurated erythema; livedo; purpura | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | Prednisone, 20 mg/d | 74 | Complete response |

| 8/M/40s | Indurated erythema; livedo; cutaneous ulcer | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | Prednisone, 30 mg/d, aspirin, sarpogrelate hydrochloride and colchicine, and azathioprine sodium | 103 | Prednisone, 8 mg/d, endoxan, and warfarin |

| 9/F/10s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | NSAIDs | 28 | Complete response |

| 10/F/50s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | Prednisone, 40 mg/d, endoxan pulse, and diaminodiphenyl sulfone benzoate, 50 mg/d | 95 | Betamethasone, 1.8 mg/d, aspirin, and tocopherol acetate |

| 11/F/10s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | Aspirin | 78 | Complete response |

| 12/F/40s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | Prednisone, 20 mg/d, and aspirin | 64 | Aspirin |

| 13/M/60s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | Prednisone, 15 mg/d, and aspirin | 27 | Prednisone, 7 mg/d, and aspirin |

| 14/M/60s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | Prednisone, 30 mg/d, aspirin, and clopidogrel bisulfate | 42 | Prednisone, 5 mg/d, aspirin, and clopidogrel bisulfate |

| 15/F/60s | Indurated erythema; livedo; cutaneous ulcer | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | Prednisone, 10 mg/d | 25 | Death due to cancer |

| 16/F/20s | Livedo | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | Prednisone, 20 mg/d, aspirin, and clopidogrel bisulfate | 28 | Complete response |

| 17/F/20s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | − | − | - | − | − | − | Prednisone, 20 mg/d, aspirin, and clopidogrel bisulfate | 19 | Aspirin and clopidogrel bisulfate |

| 18/F/40s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | Aspirin and clopidogrel bisulfate | 19 | Aspirin and clopidogrel bisulfate |

| 19/F/60s | Indurated erythema | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | Prednisone, 10 mg/d, aspirin, and clopidogrel bisulfate | 11 | Prednisone, 7.5 mg/d, aspirin, and clopidogrel bisulfate |

| 20/F/70s | Indurated erythema; livedo | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | Prednisone, 20 mg/d | 10 | Prednisone, 3 mg/d, and asprin |

| 21/F/50s | Livedo | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | Prednisone, 30 mg/d, endoxan, aspirin, and clopidogrel bisulfate | 8 | Aspirin and clopidogrel bisulfate |

Abbreviations: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; minus sign, absent; plus sign, present.

Indicates marked hydrarthrosis of bilateral knees and ankles joints.

We used the medical records of the 21 patients to determine each patient’s sex, age at diagnosis, affected anatomical sites, the type and extent of skin lesions, laboratory data, initial therapies, duration of follow-up, and current status. We also examined the following pretreatment blood indices: the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, systemic immune-inflammation index (SII; calculated as the product of the neutrophil count and the platelet count divided by the lymphocyte count7), and red cell distribution width.

In the present study, we defined relapse as the first reoccurrence or new onset of cutaneous disease that required further escalation of treatment with prednisone at a dosage of more than 20 mg/d and/or additional use of immunosuppressants observed more than 6 months after the initial therapy. This definition was based on the proposed European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for clinical studies in 2007.8

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney test and the Pearson χ2 test for the comparisons of clinical and examination variables between the groups with and without relapse, with a significance level of P < .05. The cumulative relapse rate was calculated based on the time from the date of the start of the initial therapy to the date of the first relapse as described above.

We estimated the 2-year cumulative relapse rate between groups with blood ANC above and below the median using the Kaplan-Meier method; statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp). We used the log-rank test in univariate analyses to estimate the 2-year cumulative relapse rates.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the 21 patients are summarized in Table 1. The 5 male and 16 female patients (M:F ratio, 0.3) had a median age of 49 years (range, 11-74 years) at diagnosis. The median observation period was 42 months (range, 8-374 months). The 11 patients in the nonrelapse group (M:F ratio, 0.1) had a median age of 48 years (range, 14-67 years), and the 10 patients in the relapse group (M:F ratio, 0.7) had a median age of 51 years (range, 11-65 years).

The clinical manifestations of the patients included indurated erythema in 19 (90%), livedo in 18 (86%), purpura in 5 (24%), and cutaneous ulcer in 4 (19%) (Table 1). The lower limbs were mainly affected in 19 patients (90%); upper limbs, 11 (52%); and the trunk, 5 cases (24%). A significant between-group difference was detected only in cutaneous ulcers (0 of 11 in the nonrelapse group vs 4 of 10 in the relapse group; χ21 = 4.67; P = .04). Eleven patients (52%) had neuralgia localized to the affected skin, and 10 (48%) had arthralgia; the rates between groups were not significantly different (Table 2). In the laboratory test results of the patients, significantly higher mean (SD) values were observed in the relapse group for CRP level (0.23 [2.00] vs 6.03 [3.10] mg/dL; standard error of the mean [SEM], 3.40 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.01-10.8 mg/dL; P = .01) (to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 95.2381), ANC (3.4 × 103/μL [1.1× 103/μL] vs 6.0× 103/μL [3.2× 103/μL]; SEM, 2.9× 103/μL; 95% CI, 1.9× 103/μL to 14.6× 103/μL; P = .001) (to convert to ×109 per liter, multiply by 0.001), NLR (1.4 [0.8] vs 2.8 [0.9]; SEM, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-4.9; P = .002), and SII (5.1 × 105 [3.9 × 105] vs 11.7 × 105 [7.7 × 105]; SEM, 7.3 × 105; 95% CI, 3.3 × 105 to 31.1 × 105; P = .007) (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics and Laboratory Data at Diagnosis.

| Characteristic | Study Group | Between-Group Difference (95% CI)a | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonrelapse (n = 11) | Relapse (n = 10) | |||

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Male | 1 (9) | 4 (40) | 1 [Reference] | .15 |

| Female | 10 (91) | 6 (60) | 6.67 (0.75-53.40) | |

| Purpura, No. (%) | ||||

| Absent | 9 (82) | 7 (70) | 1 [Reference] | .64 |

| Present | 2 (18) | 3 (30) | 1.93 (0.29-12.60) | |

| Cutaneous ulcer, No. (%) | ||||

| Absent | 11 (100) | 6 (60) | 1 [Reference] | .04 |

| Present | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | ∞ (1.53 to ∞) | |

| Neuralgia, No. (%) | ||||

| Absent | 7 (64) | 3 (30) | 1 [Reference] | .20 |

| Present | 4 (36) | 7 (70) | 4.08 (0.70-23.80) | |

| Arthralgia, No. (%) | ||||

| Absent | 7 (64) | 4 (40) | 1 [Reference] | .40 |

| Present | 4 (36) | 6 (60) | 2.63 (0.48-14.50) | |

| ANC, mean (SD), ×103/μL | 3.4 (1.1) | 6.0 (3.2) | 2.9 (1.9-14.6) | .001 |

| ALC, mean (SD), ×103/μL | 1.9 (0.8) | 1.9 (1.5) | 0.9 (1.0-4.5) | .94 |

| PLT, mean (SD), ×105/μL | 3.2 (0.68) | 4.2 (0.12) | 1.0 (2.1-6.6) | .31 |

| NLR, mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.9) | 1.2 (1.1-4.9) | .002 |

| PLR, mean (SD) | 160 (83.0) | 196 (68.1) | 78.1 (70.5-405.0) | .55 |

| SII, mean (SD), ×105b | 5.1 (3.9) | 11.7 (7.7) | 7.3 (3.3-31.1) | .007 |

| RDW, mean (SD), % | 14.2 (1.20) | 13.5 (1.1) | 1.3 (11.8-16.0) | .31 |

| ESR, mean (SD), mm/h | 25.0 (34.8) | 47.0 (35.2) | 37.2 (5.0-124.0) | .31 |

| CRP level, mean (SD), mg/dL | 0.23 (2.00) | 6.03 (3.10) | 3.4 (0.01-10.8) | .01 |

Abbreviations: ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLT, platelet count; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; RDW, red cell distribution width; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index.

SI conversion factors: To convert ALC and ANC to ×109 per liter, multiply by 0.001; CRP to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 95.2381.

Calculated as an odds ratio for categorical data and SEM for continuous data.

Calculated as the product of the neutrophil count and the platelet count divided by the lymphocyte count.7

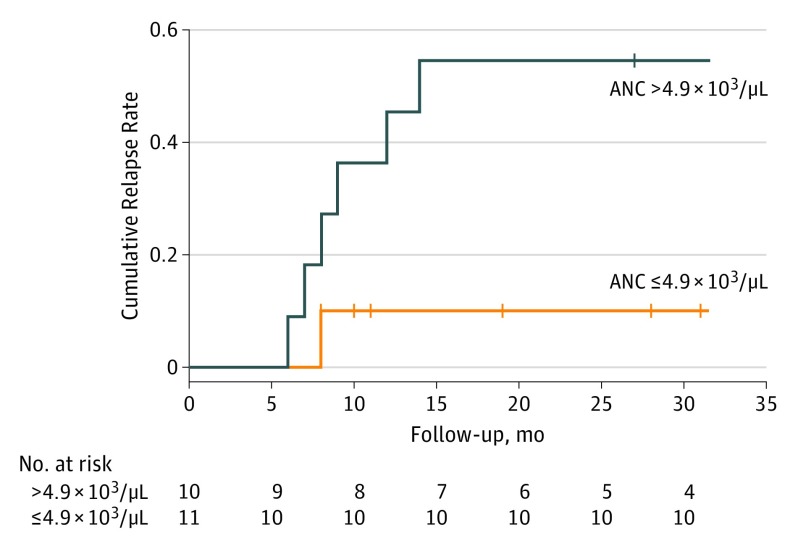

The patients’ initial therapies included prednisone in 15 (71%), cyclophosphamide in 2 (10%), azathioprine sodium in 1 (5%), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in 2 (10%), colchicine in 1 (5%), antithrombotic agents in 11 (52%), and diaminodiphenyl sulfone in 1 (5%). Three patients (14%) died of CPAN-unrelated causes. None had experienced progression to the systemic form during the observation period. The estimated 2-year cumulative relapse rate was significantly high in the patients with blood ANC above 4.9 × 103/μL compared with those with blood ANC of 4.9 × 103/μL or less (9 of 10 [90%] vs 2 of 11 [18%]; 95% CI, 6%-72%) (Figure).

Figure. Time to First Relapse After Initial Therapy by Blood Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC).

This Kaplan-Meier plot compares patients with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa and ANC values greater than 4.9 × 103/μL (n = 10) vs 4.9 × 103/μL or less (n = 11). To convert ANC values to × 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001.

Discussion

Female predominance in CPAN was reported in several studies,1,2,4,6 as well as in our cohort. Rarely, CPAN progresses to a systemic form.9 In our cohort, no patient experienced disease-specific death or progression to the systemic form during the follow-up period.

Peripheral polyneuropathy was observed in 11 patients (52%); arthralgia was observed in 10 (48%). Without exception, these symptoms were localized to the CPAN-affected skin. No patients had mononeuritis multiplex.

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa is commonly treated with antithrombotic therapies, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), colchicine, diaminodiphenyl sulfone, or warfarin potassium.1,2,4,6,10 Patients with CPAN refractory to conservative treatments may require more intensive therapeutic approaches. In our series, 16 patients (76%) were initially treated with oral prednisone, and 3 (14%) were treated with immunosuppressants. Monotherapy with antithrombotic agents (n = 2) and NSAIDs (n = 2) showed beneficial effects in 4 patients (19%).

Our analysis indicates that the clinical status of pretreatment cutaneous ulcer may be associated with a worse prognosis for CPAN involved in relapse. Other clinical symptoms such as neuropathy and arthropathy were not associated with relapse in this retrospective analysis.

Since 2005, pretreatment blood indices such as the NLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and SII were developed as clinically useful markers reflecting the general conditions of host inflammatory and immunity.7,11,12,13,14 They are variously used as prognostic predictors for cancer, metabolic syndrome, and several inflammatory conditions and for evaluating cardiovascular risk and events. In the present study, the elevated serum CRP level, blood ANC, NLR, and SII may also be associated with worse prognosis. The estimated 2-year cumulative relapse rate was significantly high in our patients with a blood ANC of above 4.9 × 103/μL.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include its retrospective design, the single tertiary medical center population, and low statistical power caused by the small sample size, which may be involved in selection biases. A multivariate regression analysis to determine independent risk factors that may influence relapse could not be applied in this study.

Conclusions

The presence of 1 or more cutaneous ulcers before treatment may be associated with a worse prognosis in CPAN. The serum CRP level, blood ANC, NLR, and SII may be useful markers of relapse of disease in patients with CPAN.

References

- 1.Daoud MS, Hutton KP, Gibson LE. Cutaneous periarteritis nodosa: a clinicopathological study of 79 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136(5):706-713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura T, Kanazawa N, Ikeda T, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: revisiting its definition and diagnostic criteria. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301(1):117-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan AJ, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a comprehensive review. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(7):750-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Criado PR, Marques GF, Morita TC, de Carvalho JF. Epidemiological, clinical and laboratory profiles of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa patients: report of 22 cases and literature review. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(6):558-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishiguro N, Kawashima M. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a report of 16 cases with clinical and histopathological analysis and a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2010;37(1):85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong JH, Huang DH, Chen ZY. Prognostic role of systemic immune-inflammation index in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(43):75381-75388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellmich B, Flossmann O, Gross WL, et al. EULAR recommendations for conducting clinical studies and/or clinical trials in systemic vasculitis: focus on anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(5):605-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen KR. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a clinical and histopathological study of 20 cases. J Dermatol. 1989;16(6):429-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawakami T, Soma Y. Use of warfarin therapy at a target international normalized ratio of 3.0 for cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):602-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horne BD, Anderson JL, John JM, et al. ; Intermountain Heart Collaborative Study Group . Which white blood cell subtypes predict increased cardiovascular risk? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(10):1638-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buyukkaya E, Karakas MF, Karakas E, et al. Correlation of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with the presence and severity of metabolic syndrome. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;20(2):159-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ha KS, Lee J, Jang GY, et al. Value of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in predicting outcomes in Kawasaki disease. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(2):301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mei Z, Shi L, Wang B, et al. Prognostic role of pretreatment blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 66 cohort studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;58:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]