This cohort study uses a self-completed questionnaire by respondents in the French NutriNet-Santé study to evaluate the association between a Mediterranean anti-inflammatory dietary profile and the severity of psoriasis.

Key Points

Question

Is there an association between the adherence to an anti-inflammatory Mediterranean diet and the onset and/or severity of psoriasis?

Findings

This prospective, web-based questionnaire study of 35 735 respondents from the French NutriNet-Santé cohort, of whom 3557 had psoriasis, found a statistically significant inverse association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and severity of psoriasis, after adjustment for sociodemographic variables and confounding factors including age, sex, physical activity, body mass index, tobacco use, educational level, a history of cardiovascular disease, and depression.

Meaning

The Mediterranean diet may slow the progression of psoriasis, so an optimized diet should be part of the multidisciplinary management of moderate to severe psoriasis.

Abstract

Importance

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to reduce chronic inflammation and has a positive effect on the risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events. Thus, we hypothesized a positive effect on the onset and/or severity of psoriasis.

Objective

To assess the association between a score that reflects the adhesion to a Mediterranean diet (MEDI-LITE) and the onset and/or severity of psoriasis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The NutriNet-Santé program is an ongoing, observational, web-based questionnaire cohort study launched in France in May 2009. The present study was performed within the framework of the NutriNet-Santé program, with data collected and analyzed between April 2017 and June 2017. Patients with psoriasis were identified via a validated online self-completed questionnaire and then categorized by disease severity: severe psoriasis, nonsevere psoriasis, and psoriasis-free. Data on dietary intake (including alcohol) were gathered during the first 2 years of participation in the cohort to calculate the MEDI-LITE score (ranging from 0 for no adherence to 18 for maximum adherence). Potentially confounding variables (eg, age, sex, physical activity, body mass index, tobacco use, and a history of cardiovascular disease) were also recorded. Analyses used adjusted multinomial logistic regression to estimate the risk of having severe psoriasis or nonsevere psoriasis compared with being psoriasis-free.

Results

Of the 158 361 total NutriNet-Santé participants, 35 735 (23%) replied to the psoriasis questionnaire. The mean (SD) age of the respondents was 47.5 (14.0) years; 27 220 (76%) of the respondents were women. Of these 35 735 respondents, 3557 (10%) individuals reported having psoriasis. The condition was severe in 878 cases (24.7%), and 299 (8.4%) incident cases were recorded (those arising more than 2 years after participant inclusion in the cohort). After adjustment for confounding factors, a significant inverse relationship was found between the MEDI-LITE score and having severe psoriasis: odds ratio (OR), 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55-0.92 for the MEDI-LITE score’s second tertile (score of 8 to 9); and OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.59-1.01 for the third tertile (score of 10 to 18).

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients with severe psoriasis displayed low levels of adherence to the Mediterranean diet; this finding supports the hypothesis that the Mediterranean diet may slow the progression of psoriasis. If these findings are confirmed, adherence to a Mediterranean diet should be integrated into the routine management of moderate to severe psoriasis.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory disease that affects 1% to 2% of the general population of all ages.1 It is thought that in genetically predisposed individuals, psoriasis is triggered by environmental factors that vary over the course of life, such as trauma, infections, stress, smoking, and the consumption of certain drugs and alcohol.2 Patients with psoriasis show a greater prevalence of obesity3 and metabolic syndrome,4 both of which confer a higher cardiovascular risk.5 Inflammation could be the link between psoriasis and obesity.3 Diet can play an important role in psoriasis. It includes many proinflammatory (eg, saturated fatty acids, heme, iron) and anti-inflammatory (eg, dietary fibers, some polyphenols) bioactive compounds.6,7 A proinflammatory diet has been associated with an increase in the incidence and severity of several inflammatory disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and rheumatoid disease.8,9 Furthermore, recent studies have shown that adherence to a healthy diet (such as the Mediterranean diet) may reduce the risk of long-term systemic inflammation10 and thus the risk of metabolic syndrome,11 cardiovascular events,12 and other chronic inflammatory diseases.12 The Mediterranean diet is characterized by a high proportion of fruits and vegetables, legumes, cereals, bread, fish, fruit, nuts, and extra-virgin olive oil, which is an important source of monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA). The consumption of meat, dairy products, eggs, and alcohol is low to moderate.13 One possible explanation for the Mediterranean diet’s ability to reduce chronic, systemic inflammation relates to the anti-inflammatory properties of dietary fibers, antioxidants, and polyphenols—all significantly present in the Mediterranean diet.14 The association between the Mediterranean diet and a lower incidence of chronic inflammatory diseases (eg, atherogenesis, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn disease) has also been supported by intervention studies.10,15,16

These dietary factors might also have an effect on the onset and/or severity of psoriasis. A review of the literature suggests that a diet rich in anti-inflammatory nutrients reduces the severity of psoriasis.17 Indeed, it has been previously reported that a low consumption of MUFA is the main predictor of the clinical severity of psoriasis; MUFA might act as an adjunctive mechanism to decrease inflammation in patients with psoriasis.18 Several studies have also reported that vitamin D may play a role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis owing to its role in proliferation and maturation of keratinocytes.19 In fact, most studies have evaluated the role of individual foods and/or nutrients (rather than a particular overall diet or healthy lifestyle) in the development of psoriasis.20

The objective of the present study was therefore to assess the association between a score that reflects the adhesion to a rather anti-inflammatory Mediterranean diet (the MEDI-LITE score21) and the onset and/or severity of psoriasis.

Methods

Study Population and Design

The present study was performed within the framework of the NutriNet-Santé program, an ongoing, observational, web-based cohort study launched in France in May 2009. Participants 18 years or older with access to the internet are eligible for the cohort. All questionnaires are completed online using a dedicated website (https://www.etude-nutrinet-sante.fr/). The NutriNet-Santé study’s rationale, design, and methodology have been described elsewhere.22 In brief, NutriNet-Santé participants provide information on sociodemographic lifestyle and anthropometric factors, health status, physical activity, and diet at the time of enrollment in the cohort and each year thereafter. The NutriNet-Santé study is being performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures have been approved by the institutional review board at the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research and the National Data Protection Commission. All participants gave their electronic, informed consent.

Case Ascertainment

A specific, validated, 11-item, online self-questionnaire on psoriasis was distributed to the whole NutriNet-Santé cohort (158 361 participants) on January 10, 2017 (eTable 1 in the Supplement).23 The participants’ responses enabled us to identify cases of psoriasis and assess disease severity when present. We also identified incident cases of psoriasis (defined as those arising more than 2 years after inclusion in the cohort), to evaluate the participants’ MEDI-LITE scores before the onset of psoriasis.

Participants were classified into 3 groups: severe psoriasis, nonsevere psoriasis, and no psoriasis. The definition of severe psoriasis was based on both physicians’ reports and patients’ outcomes: a history of hospitalization, the use of systemic medications, a self-rating of “very severe” or “severe” disease, and a self-rating of a “very severe” or “severe” impact on quality of life.

Dietary Data Collection and MEDI-LITE Score Computation

Dietary intakes were assessed every 6 months through a series of 3 nonconsecutive, validated, web-based, 24-hour dietary records, randomly assigned over a 2-week period.24,25,26 Participants reported all foods and beverages consumed during a 24-hour period.21,27,28 For each participant, we calculated the average consumption (in grams per day) for the food groups of interests (fruits, vegetables, legumes, meat, fish, cereals, olive oil, and dairy products), macronutrient and micronutrient intakes (vitamins A, C, D, and E; manganese; selenium; zinc; fiber; carbohydrates; lipids; proteins; ω-3 [omega-3], and ω-6), and alcohol intake. A Mediterranean diet adherence score (MEDI-LITE) was calculated for each participant using the average of 3 to 15 dietary records gathered during the first 2 years after inclusion. MEDI-LITE was developed by Sofi et al21 in 2014 and is based on a large-scale meta-analysis of cohort studies of the link between the Mediterranean diet and health status. The MEDI-LITE score was validated in 2017 by comparing its metrological characteristics with those of the previously validated and widely used MedDietScore.29

The MEDI-LITE score ranges from 0 (no adherence) to 18 (full adherence) and includes 3 different categories of consumption (1 for each food group composing the Mediterranean diet).

Data Collection for Covariates

At baseline and during follow-up, self-questionnaires were used to collect information on sociodemographic,30 anthropometric,31,32 lifestyle, and medical factors: sex, age, educational level, smoking habits, body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), physical activity (as assessed by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire),33 medication use, a history of cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, angina, acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery angioplasty, transient ischemic attack, or stroke), diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, IBD, and depressive symptoms (defined as a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [CES-D] score ≥16; the CES-D was incorporated into the NutriNet-Santé study in 2016).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were reported as median (interquartile range) or mean (SD). Qualitative variables were reported as the number (percentage) of participants. The characteristics of the participants who completed the psoriasis questionnaire were compared with those of the participants who did not reply (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Unadjusted comparisons among the severe psoriasis, nonsevere psoriasis, and no psoriasis groups were based on an analysis of variance for quantitative variables and on the χ2 test for qualitative variables. Multinomial logistic regression models with the MEDI-LITE score as the main exposure were adjusted for patient-related covariates (in tertiles, ranging from minimum to maximum adherence; tertile 1, a MEDI-LITE score of 0-7; tertile 2, a score of 8-9; tertile 3a score of 10-18). Analysis was performed on the basis of 4 models:

Model 1, adjusted for age and sex;

Model 2, adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, and educational level;

Model 3, adjusted for age, sex BMI, smoking status, physical activity, educational level, and baseline history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and hypertriglyceridemia; and

Model 4, adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, educational level, and baseline history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and depressive symptoms.

The results of the multivariable analyses for the MEDI-LITE score were presented as continuous variables and (assuming that the nonlinear hypothesis held true) in tertiles.

Sensitivity Analyses

To minimize selection bias, the sensitivity analyses (1) included only participants with physician-diagnosed psoriasis and (2) excluded those with other diseases with a predetermined genetic basis similar to that of psoriasis and known to be related to diet (eg, IBD and/or ongoing systemic treatment with methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, and/or biologics).

To limit classification bias, the second sensitivity analysis included only participants with severe psoriasis who reported a history of hospitalization and/or the use of systemic therapy.

Finally, we restricted our analyses to incident cases of psoriasis; this limited the influence of confounding factors that may have modified dietary behavior after the diagnosis of psoriasis and that had not been taken into account in our final model.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05. All analyses were performed with SAS software (SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1, SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

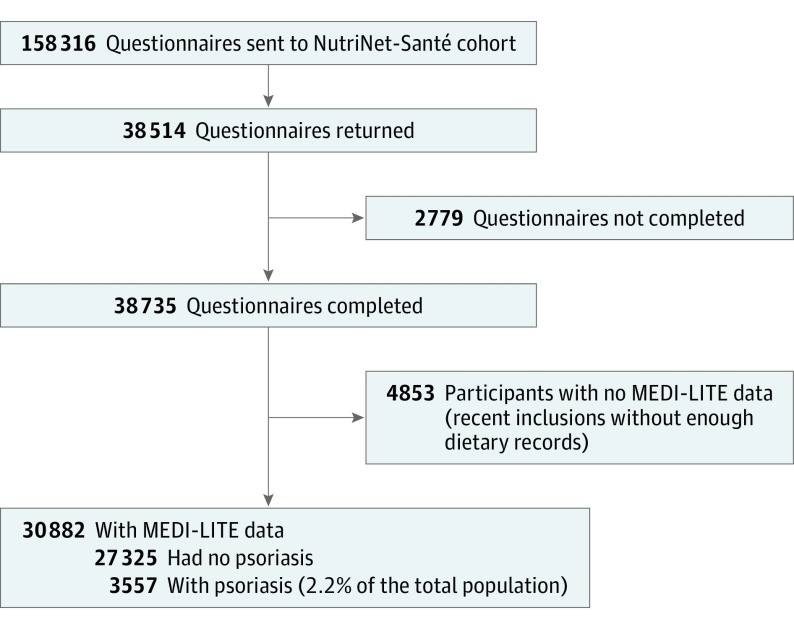

Among the 35 735 participants (22.6% of the all cohort) who replied to the optional online psoriasis questionnaire, 27 220 were women (76.2%), and 8515 were men (23.8%), with a mean (SD) age of 47.5 (14.0) years (Figure and Table 1). The participants who completed the psoriasis questionnaire (ie, responders) did not differ significantly from the nonresponders except that the nonresponder group had a younger mean age and a higher proportion of active smokers (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Figure. Study Flowchart.

A total of 35 735 respondents of the 158 361 NutriNet-Santé participants replied to the psoriasis optional questionnaire. Of these, 4853 participants with no MEDI-LITE data were excluded, and 3557 individuals had psoriasis.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) (n = 35 735) |

|---|---|

| Psoriasis | 3557 (9.95) |

| Diagnosed by a dermatologist | 2032 (57.13) |

| Diagnosed by a physician (dermatologists and others) | 3096 (87.03) |

| Age at onset, mean (SD), y | 29.5 (16.61) |

| Incident psoriasis | 299 (0.83) |

| Severe psoriasisa | 878 (2.46) |

| Previous hospitalization for psoriasis | 23 (0.65) |

| Systemic treatment for psoriasis | 431 (12.12) |

| Psoriasis reported by the patient as severe or very severe | 399 (21.23) |

| Impact on daily life reported as severe or very severe | 448 (23.84) |

| Topical-only treatment or alternative medicine | 2775 (78.02) |

| Psoriasis still active at the time of the questionnaire | 1872 (52.63) |

Participants with severe psoriasis were defined as those who reported a history of hospitalization, the use of systemic treatment, self-reported severe or very severe psoriasis, and/or a severe or very severe impact on quality of life.

Data on the MEDI-LITE score and the different food groups and nutrients were available for 30 882 patients. The 4853 participants with missing data (corresponding to 13.6% of the responders) had recently joined the cohort and thus lacked sufficient dietary records; accordingly, they were excluded from the analyses. The groups of included and excluded persons did not differ significantly with regard to sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities (ie, age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, educational level, health status, and personal medical history; data not shown).

A total of 3557 patients indicated that they had psoriasis, corresponding to 10.0% of the responders, and 2.2% of the whole NutriNet-Santé population. Of the 3557 patients with psoriasis, 878 (corresponding to 24.7%) reported severe psoriasis and 299 (8.4%) had incident psoriasis (arising more than 2 years after inclusion in the cohort).

Factors Associated With the Severity of Psoriasis

The results of the univariate analyses are summarized in Table 2. Patients with severe psoriasis had a higher risk of having a MEDI-LITE score of 0 to 7 (first tertile, low adherence to the Mediterranean diet) (n = 339; 46%) compared with patients with no severe psoriasis (n = 839; 36%) and patients with no psoriasis (n = 9915; 36%). As detailed in Table 2, associations were also noted for sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, educational level, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, and depression.

Table 2. Univariate Analyses in the Study Population of 30 882 Survey Respondentsa.

| Characteristic | Psoriasis Statusb | P Valuec | Missing Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe (n = 746, 2.4%) | Nonsevere (n = 2308, 7.5%) | None (n = 27 828, 90.1%) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46.75 (0.5) | 48.32 (0.3) | 47.81 (0.1) | .03 | NA |

| Female | 574 (76.9) | 1663 (72.1) | 21 310 (76.6) | <.001 | NA |

| BMI | |||||

| <25 | 459 (61.6) | 1473 (63.8) | 19 661 (70.7) | NA | 11 (0) |

| 25-30 | 172 (23.1) | 565 (24.5) | 6023 (21.6) | NA | NA |

| >30 | 114 (15.3) | 269 (11.7) | 2135 (7.7) | <.001 | NA |

| Physical activity | |||||

| High | 235 (36.5) | 701 (34.5) | 8555 (34.7) | .89 | 3559 (11.5) |

| Moderate | 265 (41.2) | 884 (43.5) | 10 725 (43.5) | NA | NA |

| Low | 144 (22.4) | 447 (22) | 5367 (21.8) | NA | NA |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 322 (43.2) | 1008 (43.7) | 14 462 (51.9) | <.001 | NA |

| Former | 292 (39.1) | 949 (41.1) | 10 010 (35.9) | NA | NA |

| Current | 132 (17.7) | 351 (15.2) | 3356 (12.1) | NA | NA |

| Education | |||||

| Primary | 25 (3.6) | 60 (2.8) | 698 (2.7) | .08 | 2273 (7.3) |

| Secondary | 128 (18.2) | 371 (17.3) | 4318 (16.8) | NA | NA |

| Higher | 549 (78.2) | 1707 (79.8) | 20 753 (80.5) | NA | NA |

| Medical history | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 38 (5.6) | 59 (2.6) | 581 (2.1) | <.001 | NA |

| Arterial hypertension | 106 (14.2) | 336 (14.6) | 3095 (11.1) | <.001 | NA |

| Diabetes | 30 (4.0) | 66 (2.9) | 590 (2.1) | <.001 | NA |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 20 (2.7) | 54 (2.3) | 479 (1.7) | .005 | NA |

| Depression, mean (SD) CES-D scored | 12.65 (0.4) | 10.72 (0.2) | 9.88 (0.1) | <.001 | 11 501 (37.2) |

| MEDI-LITE score | |||||

| Continuous score, mean (SD) | 7.9 (0.08) | 8.3 (0.05) | 8.4 (0.01) | <.001 | NA |

| Tertile 1 (0-7) | 339 (45.5) | 839 (36.3) | 9915 (35.6) | <.001 | NA |

| Tertile 2 (8-9) | 217 (29) | 751 (32.5) | 9114 (32.7) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3 (10-18) | 190 (25.5) | 718 (31.1) | 8799 (31.6) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MEDI-LITE, Mediterranean Diet Adherence score.

Data on the MEDI-LITE score and the different food groups and nutrients were available for 30 882 respondents.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are reported as number (percentage) of participants.

P value from a χ2 or Fisher exact test.

Depression is defined as a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) score ≥16.

In a multivariable analysis, the MEDI-LITE score was significantly and inversely associated with the severity of psoriasis in models 1, 2, and 3 (supporting data reported in Table 3). There was also an association found in model 4, but the association was not statistically significant (Table 3). Participants with severe psoriasis had a lower MEDI-LITE score (ie, less adherence to the Mediterranean diet) than participants with nonsevere psoriasis and psoriasis-free participants.

Table 3. Multivariable Analyses in the Total Study Population.

| Modela | Psoriasis Severityb | OR (95%CI)c | P Value for Trend | Continuous, OR (95%CI)c | P Value Linear | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertile 1 (n = 11 093) | Tertile 2 (n = 10 082) | Tertile 3 (n = 9707) | |||||

| Model 1 (n = 30 882) | Nonsevere | 1 [Reference] | 0.97 (0.88-1.08) | 0.96 (0.86-1.06) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | <.001 |

| Severe | 1 [Reference] | 0.70 (0.59-0.84) | 0.64 (0.53-0.77) | 0.92 (0.89-0.95) | |||

| Model 2 (n = 25 401) | Nonsevere | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (0.91-1.14) | 1.09 (0.97-1.23) | <.001 | 1.01 (0.98-1.03) | .01 |

| Severe | 1 [Reference] | 0.73 (0.60-0.89) | 0.73 (0.59-0.89) | 0.94 (0.91-0.98) | |||

| Model 3 (n = 25 401) | Nonsevere | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (0.91-1.15) | 1.09 (0.97-1.23) | .005 | 1.01 (0.98-1.03) | .01 |

| Severe | 1 [Reference] | 0.74 (0.61-0.90) | 0.74 (0.60-0.91) | 0.94 (0.91-0.98) | |||

| Model 4 (n = 21 180) | Nonsevere | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (0.88-1.19) | 1.08 (0.93-1.26) | .06 | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | .16 |

| Severe | 1 [Reference] | 0.71 (0.55-0.92) | 0.78 (0.59-1.01) | 0.955 (0.911-1.002) | |||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); MEDI-LITE, Mediterranean diet adherence score; OR, odds ratio.

Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, and educational level. Model 3 was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, educational level, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and hypertriglyceridemia. Model 4 was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, educational level, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and depressive symptoms.

Reference is no psoriasis.

The MEDI-LITE score range for tertile 1 was 0 to 7; for tertile 2 it was 8 to 9; for tertile 3 it was 10 to 18. Odds ratios (95% CIs) were estimated using multinomial logistic regression and adjusted for matching variables.

Sensitivity Analyses

The results of the multivariable analyses were similar when we considered only patients participants diagnosed with psoriasis by a physician (whether a dermatologist or not; n = 2655 cases of psoriasis, including 712 severe cases) or a dermatologist in particular, (n = 1755, including 566 severe cases), and excluded participants with IBD and/or systemic treatment (sample: 731 severe psoriasis, 2275 nonsevere psoriasis, and 27 571 psoriasis-free participants). Likewise, similar results were obtained when the definition of severe psoriasis was based solely on a history of hospitalization and/or systemic therapy for psoriasis (sample: n = 441). Finally, a multivariable analysis of the 299 cases of incident psoriasis yielded much the same odds ratios as the analysis of the total population (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

The present study of the MEDI-LITE score revealed an inverse association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and the severity of psoriasis. This association was still present after adjustment for sociodemographic variables, history of cardiovascular disease, and depression. Thus, patients with severe psoriasis adhered less strongly to the Mediterranean diet; this finding may support the hypothesis that the Mediterranean diet is associated with less severe psoriasis (as proven for other inflammatory diseases).15,16

To our knowledge, only 1 study has reported an association between psoriasis and the Mediterranean diet. In a cross-sectional study, Barrea et al34 found an association between the adherence to the Mediterranean diet on one hand and the severity of psoriasis (as assessed by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index) and serum C-reactive protein levels on the other. Indeed, the proportion of individuals with low adherence to the Mediterranean diet was higher in a group of patients with psoriasis than in a psoriasis-free control group matched for age, sex, and BMI. However, the study’s design and small sample size (n = 62 patients with psoriasis) constitute major limitations.34

Our present results from a cross-sectional observational study neither prove the existence of a direct, causal relationship between psoriasis and diet nor provide mechanistic information on the relationship. However, a number of hypotheses can be justifiably considered.

First, a proinflammatory diet might trigger psoriasis. The results of a recent study emphasized the major impact of nutrition on the immune system.35 The lymphoid organs and the cells of the immune system (most of which are present in the gastrointestinal tract) are directly influenced by the environment in general and food in particular, from embryogenesis onwards. Notably, polyunsaturated fatty acids, ω-3 fatty acids, folates, and vitamins A, D, and E may have a special role by virtue of their anti-inflammatory actions.14,17 Furthermore, a specific diet may alter the intestinal microbiota and thus promote inappropriate immune responses (eg, alteration of the T-regulatory cell–T helper cell type 17 balance) that can trigger digestive and systemic autoimmune diseases. In managing IBD, an anti-inflammatory diet with high probiotic and ω-3 contents might be of value because of its direct action on the intestinal microbiome.8 Also, diet can alter the expression of various immunity-related genes through epigenetic modification; this constitutes an additional link between the environment, nutrition, and disease.35 Changes in Western diets over recent decades (eg, to include highly processed foods that are low in micronutrients) might explain the increased incidence of allergic, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases.35 In the present study, there seems to be an inverse association between MEDI-LITE score and severity of incident cases of psoriasis. The absence of significance could be explained by a lack of power: of the 299 incident cases of psoriasis, severe psoriasis was limited to 69.

Second, a proinflammatory diet might aggravate psoriasis. It is already known that consumption of a proinflammatory diet is linked to an increased risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome36—both of which are associated with more severe psoriasis37 and a higher cardiovascular risk. A growing body of evidence supports the presence of multiple associations among obesity, metabolic syndrome, and psoriasis, and there is probably a bidirectional association between obesity and psoriasis.3 Indeed, the severities of psoriasis, metabolic syndrome, and systemic inflammation are interrelated. For example, Vadakayil et al38 have reported higher serum C-reactive protein levels in patients with severe psoriasis and/or metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, more severe systemic inflammation may be associated with high blood pressure, the dysregulation of blood lipids, and disorders of carbohydrate metabolism—all of which would aggravate the symptoms of psoriasis.39 Hence, in patients with psoriasis, a proinflammatory diet would probably accentuate systemic inflammation and worsen the skin lesions. In line with this hypothesis, several interventional studies have shown that dietary measures can decrease the severity of psoriasis.14,17,40

Third, psoriasis might directly and causally alter eating behavior. This potential reverse causality bias cannot be excluded in the present study owing to the cross-sectional design of the survey. Environmental factors (such as sociodemographic factors and depression) are known to have an impact on diet quality.41 In the present study, our multivariate analyses took account of the main confounding factors and did not modify the results of unadjusted analysis. However, other confounding factors may have been present. Indeed, published studies of the association between psoriasis and various foods and nutrients14,15 might induce patients to modify their eating behaviors—despite the absence of formal guidelines. In a recent study,42 1206 patients with psoriasis filled out a dietary questionnaire; 86% of the participants stated that they had changed their diet (eg, with a decrease in alcohol and carbohydrate intakes, and an increase in fruit, vegetable, and vitamin D intakes) to improve their skin condition.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study had a number of strengths and limitations. The strengths include the large sample in NutriNet-Santé cohort and the high accuracy of the food records. Indeed, food consumption was evaluated through at least 3 food surveys and a large food database (with more than 3300 items); this allowed intra-individual variability to be taken into account.43

The fact that NutriNet-Santé participants are all volunteers may limit the present results’ generalizability; the cohort participants are likely to be more concerned about their health status than the general population. However, 87% of the NutriNet-Santé participants having reported psoriasis stated that this had been diagnosed by a physician, which minimizes classification bias. Furthermore, the psoriasis questionnaire used in the present study was derived from a self-questionnaire with known, validated metrological properties; in the previous study,23 patients who reported “having a psoriasis” and “it was diagnosed by a physician” accurately reported their diagnosis, with high sensitivity (93%) and specificity (98%). The prevalence of psoriasis was estimated at 2.2% (n = 3557 out of 158 361), assuming that the participants who did not reply did not have a psoriasis; such prevalence is expected in a French population.1 The association between severe psoriasis and low adherence to the Mediterranean diet persisted after adjustment for known confounding factors, thus minimizing residual confounding bias. The severity of psoriasis was defined using both usual physicians’ assessment (hospitalization and systemic treatment for psoriasis) and patients’ self-reported severity. However, similar results were obtained when the definition of severe psoriasis was based solely on a history of hospitalization and/or systemic therapy with psoriasis medications, thus minimizing classification bias. Nevertheless, the proportion of missing data for depression was high (37%): the CES-D score that we took into account was incorporated into the NutriNet-Santé program in 2016 and thus was not administered to all participants. We did not use a multiple imputation method because of the high proportion of missing data (37%).44

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present results suggest an inverse association between a Mediterranean (anti-inflammatory) diet and the severity of psoriasis. This association was independent of a number of sociodemographic variables and confounding medical factors. Further prospective observational studies and randomized clinical trials are needed to confirm these results, and experimental data are needed to establish the mechanistic links between psoriasis and diet. If these findings are confirmed, an optimized diet should be part of the multidisciplinary management of moderate to severe psoriasis, with a view to increasing therapeutic effectiveness.

eTable 1. Self-questionnaire on psoriasis

eTable 2. Comparison of responders (n=35,735) with non-responders (n=146,321)

eTable 3. Multivariate analyses in the incident population

References

- 1.Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):496-509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trojacka E, Zaleska M, Galus R. Influence of exogenous and endogenous factors on the course of psoriasis [in Polish]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2015;38(225):169-173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:e54. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2012.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voiculescu VM, Lupu M, Papagheorghe L, Giurcaneanu C, Micu E. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome—scientific evidence and therapeutic implications. J Med Life. 2014;7(4):468-471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahwan KT, Kimball AB. Psoriasis and cardiovascular disease. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(6):1227-1242. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrea L, Nappi F, Di Somma C, et al. Environmental risk factors in psoriasis: the point of view of the nutritionist. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(5):743. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13070743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Hébert JR. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(8):1689-1696. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013002115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, Ma Y, Baldwin KR, Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report. Nutr J. 2014;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semerano L, Julia C, Aitisha O, Boissier MC. Nutrition and chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84(5):547-552. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akbaraly TN, Shipley MJ, Ferrie JE, et al. Long-term adherence to healthy dietary guidelines and chronic inflammation in the prospective Whitehall II study. Am J Med. 2015;128(2):152-160.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salas-Salvadó J, Guasch-Ferré M, Lee C-H, Estruch R, Clish CB, Ros E. Protective effects of the Mediterranean diet on type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. J Nutr. 2016;jn218487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esposito K, Giugliano D. Mediterranean diet for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):674-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. ; Mediterranean Diet Foundation Expert Group . Mediterranean diet pyramid today: science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(12A):2274-2284. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guida B, Napoleone A, Trio R, et al. Energy-restricted, ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids-rich diet improves the clinical response to immuno-modulating drugs in obese patients with plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized control clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(3):399-405. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto Y, Sugioka Y, Tada M, et al. Monounsaturated fatty acids might be key factors in the Mediterranean diet that suppress rheumatoid arthritis disease activity: the TOMORROW study. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(2):675-680. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marlow G, Ellett S, Ferguson IR, et al. Transcriptomics to study the effect of a Mediterranean-inspired diet on inflammation in Crohn’s disease patients. Hum Genomics. 2013;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-7-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, Debbaneh M, Koo J, Liao W. Diet and psoriasis, part III: role of nutritional supplements. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):561-569. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0658-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrea L, Savanelli MC, Di Somma C, et al. Vitamin D and its role in psoriasis: an overview of the dermatologist and nutritionist. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(2):195-205. doi: 10.1007/s11154-017-9411-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson PB. Is dietary supplementation more common among adults with psoriasis? results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(1):159-165. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sofi F, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Mediterranean diet and health status: an updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(12):2769-2782. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013003169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hercberg S, Castetbon K, Czernichow S, et al. The NutriNet-Santé Study: a web-based prospective study on the relationship between nutrition and health and determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phan C, Ezzedine K, Lai C, et al. Agreement between self-reported inflammatory skin disorders and dermatologists’ diagnosis: a cross-sectional diagnostic study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(10):1243-1244. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lassale C, Castetbon K, Laporte F, et al. Correlations between fruit, vegetables, fish, vitamins, and fatty acids estimated by web-based nonconsecutive dietary records and respective biomarkers of nutritional status. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(3):427-438.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, Méjean C, et al. Comparison between an interactive web-based self-administered 24 h dietary record and an interview by a dietitian for large-scale epidemiological studies. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(7):1055-1064. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Moulenc N, Deheeger M, Preziozi P, et al. Validation of the food portion size booklet used in the SU.VI.-MAX study [in French]. Cah Nutr Diét. 1996;31:158-164. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnault N, Caillot L, Keal C.. Food Composition Table, NutriNet-Sante Study [in French]. Paris, France: Les editions INSERM/Economica; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Black AE. Critical evaluation of energy intake using the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake: basal metabolic rate: a practical guide to its calculation, use and limitations. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(9):1119-1130. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sofi F, Dinu M, Pagliai G, Marcucci R, Casini A. Validation of a literature-based adherence score to Mediterranean diet: the MEDI-LITE score. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2017;68(6):757-762. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2017.1287884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergnaud AC, Touvier M, Méjean C, et al. Agreement between web-based and paper versions of a socio-demographic questionnaire in the NutriNet-Santé study. Int J Public Health. 2011;56(4):407-417. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0257-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lassale C, Péneau S, Touvier M, et al. Validity of web-based self-reported weight and height: results of the NutriNet-Santé study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e152. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Touvier M, Méjean C, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Comparison between web-based and paper versions of a self-administered anthropometric questionnaire. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(5):287-296. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9433-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.IPAQ Group Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). http://www.ipaq.ki.se. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- 34.Barrea L, Balato N, Di Somma C, et al. Nutrition and psoriasis: is there any association between the severity of the disease and adherence to the Mediterranean diet? J Transl Med. 2015;13:18. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0372-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Rosa V, Galgani M, Santopaolo M, Colamatteo A, Laccetti R, Matarese G. Nutritional control of immunity: Balancing the metabolic requirements with an appropriate immune function. Semin Immunol. 2015;27(5):300-309. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vahid F, Shivappa N, Karamati M, Naeini AJ, Hebert JR, Davoodi SH. Association between Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) and risk of prediabetes: a case-control study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2017;42(4):399-404. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kothiwala SK, Khanna N, Tandon N, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular changes in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis and their correlation with disease severity: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(5):510-518. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.183638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vadakayil AR, Dandekeri S, Kambil SM, Ali NM. Role of C-reactive protein as a marker of disease severity and cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(5):322-325. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.164483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emchenko IaA. Dependence of clinical and laboratory indicators of the level of systemic inflammation in patients with psoriasis of moderate severity with concomitant metabolic syndrome [in Russian]. Georgian Med News. 2014;(236):43-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jensen P, Christensen R, Zachariae C, et al. Long-term effects of weight reduction on the severity of psoriasis in a cohort derived from a randomized trial: a prospective observational follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(2):259-265. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.125849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viñuales I, Viñuales M, Puzo J, Sanclemente T. Sociodemographic factors associated with adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern in elderly people [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2016;51(6):338-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a US national survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(2):227-242. doi: 10.1007/s13555-017-0183-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fassier P, Zelek L, Lécuyer L, et al. Modifications in dietary and alcohol intakes between before and after cancer diagnosis: results from the prospective population-based NutriNet-Santé cohort. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(3):457-470. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Self-questionnaire on psoriasis

eTable 2. Comparison of responders (n=35,735) with non-responders (n=146,321)

eTable 3. Multivariate analyses in the incident population