Abstract

This cross-sectional survey study investigates how older US adults want their health care clinicians to frame discussions about stopping routine cancer screening.

Clinical practice guidelines recommend against routine cancer screening in older adults in whom the potential harms of screening outweigh the benefits, which are often defined by specific age or life expectancy thresholds.1,2 However, many older adults who meet these thresholds for stopping routine screening continue to undergo screening for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers.3 One contributor to this discrepancy may be that clinicians are uncomfortable discussing cancer screening cessation. This project aimed to identify older adults’ preferred communication strategies for clinicians to use when discussing stopping cancer screening.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey using a probability-based online panel (KnowledgePanel) representative of US adults. KnowledgePanel is a product of GfK, a survey research firm, and panel members are recruited by random digit dialing and address-based sampling. Among 1272 eligible panel members (aged ≥65 years, English-speaking) invited to participate, 881 (69.3%) completed the survey in November 2016. We used the best-worst scaling method to test the participants’ preferences for 13 different phrases that a clinician may use to explain why a patient should not undergo a routine cancer screening test.4 The phrases were identified from previous qualitative interviews with older adults and primary care physicians5,6 and literature review (Figure). Participants were randomized to questions about prostate or breast cancer screening or colorectal cancer screening. As noted at the beginning of the online survey, completion of the survey served as consent to participate in the research study. This project was approved by a Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

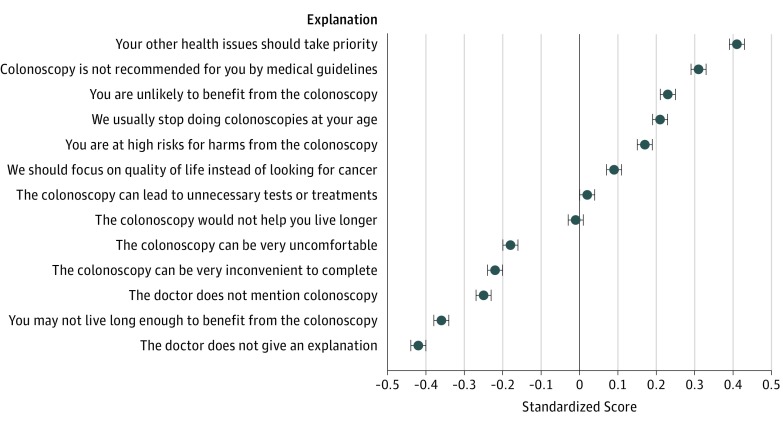

Figure. Relative Preference of 881 Older Adults Regarding 13 Phrases a Clinician May Use to Explain Stopping Routine Cancer Screening.

Standardized scores indicating the strength of preference range from −1.0 (worst) to 1.0 (best). Surveys asked about colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer screening, with questions differing only in the name of the test. The term colonoscopy was used in surveys that asked about colorectal cancer screening; mammogram, in surveys that asked about breast cancer screening; and prostate-specific antigen (PSA), in surveys that asked about prostate cancer screening.

Best-worst scaling is a stated-preference research method that allows relative preferences to be quantified and compared across objects, which is not possible with traditional Likert scales.4 We constructed 13 choice tasks, each displaying 4 of the 13 phrases, and asked participants to choose 1 best phrase and 1 worst phrase in each choice task. A standardized score was calculated for each phrase by dividing the sum of assigned values (1 each time a phrase was chosen as best, −1 each time chosen as worst) by the number of times the phrase was presented in the survey. The score indicates the relative strength of the preference for a phrase and ranges from −1.0 (least preferred) to 1.0 (most preferred). Survey weights were applied to adjust for nonresponse and oversampling of African Americans. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp).

Results

The mean (SD) age of the 881 participants was 73.4 (6.1) years, and 464 (55.2%) were female. Five hundred seventy-six participants (77.2%) were white, non-Hispanic; 216 (8.8%) were African American, non-Hispanic; 47 (8.2%) were Hispanic; and 42 (5.8%) were of another race/ethnicity. Six hundred thirty-one participants (66.0%) had undergone a mammogram or prostate-specific antigen test within the preceding 2 years or a colonoscopy within the preceding 10 years (Table). The most preferred phrase to explain stopping cancer screening was “your other health issues should take priority” (mean score, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.39-0.43), and the least preferred option was “the doctor does not give an explanation” (score, −0.42; 95% CI, −0.44 to −0.40) (Figure). Other more preferred phrases included references to guidelines, older age, the lack of benefit, and the high risk for harm from the screening test. Less preferred were phrases that mentioned life expectancy, the discomfort or inconvenience of the screening test, and the clinician not bringing up a discussion of cancer screening. Separate analyses by cancer screening type found minimal differences in the preference rankings or the standardized scores of the phrases across cancer screening types.

Table. Characteristics of 881 Study Participantsa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 73.4 (6.1) |

| Female sex | 464 (55.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 576 (77.2) |

| African American, non-Hispanic | 216 (8.8) |

| Hispanic | 47 (8.2) |

| Other | 42 (5.8) |

| Survey type | |

| Breast cancer screening | 232 (27.7) |

| Prostate cancer screening | 208 (22.5) |

| Colorectal cancer screening | 441 (49.8) |

| Has ever had a mammogram or PSA test or colonoscopyb | 744 (81.2) |

| Has had an up-to-date mammogram or PSA test or colonoscopyc | 631 (66.0) |

| Physician has recommended stopping mammogram or PSA test or colonoscopy | 76 (9.7) |

| Estimated life expectancy, yd | |

| >10 | 631 (68.9) |

| 4-10 | 180 (27.0) |

| <4 | 17 (4.1) |

| Educational level | |

| Did not complete high school | 61 (14.4) |

| Completed high school | 271 (33.3) |

| <4 y College | 243 (24.1) |

| College graduate or postgraduate degrees | 306 (28.2) |

| Health literacy, mean (SD), scoree | 13.1 (2.1) |

| Numeracy, mean (SD), scoref | 13.8 (3.5) |

| Screening attitude: “I plan to get screened for breast/prostate/colorectal cancer for as long as I live” | |

| Strongly agree | 81 (7.9) |

| Somewhat agree | 219 (24.0) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 260 (29.3) |

| Somewhat disagree | 190 (22.9) |

| Strongly disagree | 76 (10.4) |

| Not applicable owing to history of cancer | 52 (5.5) |

Abbreviation: PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Means and percentages are weighted.

Participants randomized to breast cancer screening questions were asked about receipt of mammogram; participants randomized to prostate cancer screening questions, prostate-specific antigen test; and participants randomized to colorectal cancer screening questions, colonoscopy.

Up-to-date mammogram and PSA test were defined to be within 2 years; up-to-date colonoscopy, within 10 years.

According to the mortality risk index developed by Cruz et al (JAMA. 2013;309[9]:874-876), a median life expectancy of greater than 10 years is defined as a mortality risk of less than 50% across 10 years; a median life expectancy of between 4 and 10 years is defined as a greater than 50% mortality risk across 10 years and less than 50% mortality risk across 4 years; a median life expectancy of less than 4 years is defined as a greater than 50% mortality risk across 4 years.

Health literacy was measured using a validated 3-item scale developed by Chew et al (Fam Med. 2004;36[8]:588-594). Possible scores range from 3 to 15; higher scores indicate greater health literacy.

Subjective numeracy was measured using a validated 3-item scale developed by McNaughton et al (Med Decis Making.2015;35[8]:932-936). Possible scores range from 3 to 18; higher scores indicate greater numeracy.

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to characterize and quantify older adults’ preferences for how clinicians can discuss stopping breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer screenings. Although the study relied on a hypothetical scenario, this approach allowed us to elicit perspectives from a large national sample. Consistent with results from an earlier qualitative study,5 we found that the most preferred explanation centered on a priority shift to focus on other health issues. Explanations that mentioned guidelines and that mentioned older age were also highly rated, whereas mentioning life expectancy ranked low. Clinical practice guidelines increasingly advocate using life expectancy to inform cancer screening recommendations,1,2 and our findings highlight the importance of communicating these guidelines in language that is acceptable to and preferred by patients. In particular, framing the discussion around lack of benefit, without necessarily mentioning life expectancy, may be a more appealing communication strategy. Simply omitting discussion about cancer screening as a way to stop screening was not a preferred approach, which raises an ethical dilemma about whether an opportunity to discuss stopping cancer screening should at least be offered by clinicians.

References

- 1.Harris RP, Wilt TJ, Qaseem A; High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians . A value framework for cancer screening: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):712-717. doi: 10.7326/M14-2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotwal AA, Schonberg MA. Cancer screening in the elderly: a review of breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer screening. Cancer J. 2017;23(4):246-253. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royce TJ, Hendrix LH, Stokes WA, Allen IM, Chen RC. Cancer screening rates in individuals with different life expectancies. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1558-1565. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best-worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ. 2007;26(1):171-189. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences about cancer screening cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1121-1128. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL II, Cayea D, Boyd C, Feeser S, Pollack CE. Discussion strategies that primary care clinicians use when stopping cancer screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):e221-e223. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]