Key Points

Question

Does a telephone call from a nurse after routine pediatric discharge prevent use of urgent health care services?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 966 children discharged from a general medicine hospital service, children randomized to the intervention had similar reutilization rates for urgent health care services compared with children randomized to standard discharge.

Meaning

Telephone calls from a nurse after pediatric discharge do not result in decreased reutilization rates for urgent health care services.

Abstract

Importance

Families often struggle after discharge of a child from the hospital. Postdischarge challenges can lead to increased use of urgent health care services.

Objective

To determine whether a single nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge decreased the 30-day reutilization rate for urgent care services and enhanced overall transition success.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This Hospital-to-Home Outcomes (H2O) randomized clinical trial included 966 children and adolescents younger than 18 years (hereinafter referred to as children) admitted to general medicine services at a free-standing tertiary care children’s hospital from May 11 through October 31, 2016. Data were analyzed as intention to treat and per protocol.

Interventions

A postdischarge telephone call within 4 days of discharge compared with standard discharge.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the 30-day reutilization rate for urgent health care services (ie, unplanned readmission, emergency department visit, or urgent care visit). Secondary outcomes included additional utilization measures, as well as parent coping, return to normalcy, and understanding of clinical warning signs measured at 14 days.

Results

A total of 966 children were enrolled and randomized (52.3% boys; median age [interquartile range], 2.4 years [0.5-7.8 years]). Of 483 children randomized to the intervention, the nurse telephone call was completed for 442 (91.5%). Children in the intervention and control arms had similar reutilization rates for 30-day urgent health care services (intervention group, 77 [15.9%]; control group, 63 [13.1%]; P = .21). Parents of children in the intervention group recalled more clinical warning signs at 14 days (mean, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.7-2.0] in the intervention group; 1.5 [95% CI, 1.4-1.6] in the control group; ratio of intervention to control, 1.2 [95% CI, 1.1-1.3]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Although postdischarge nurse contact did not decrease the reutilization rate of postdischarge urgent health care services, this method shows promise to bolster postdischarge education.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02081846

This randomized clinical trial examines whether a single nurse-led telephone call decreased 30-day reutilization rates for urgent care services and enhanced overall transition success among children discharged from a general medicine service of a children’s hospital.

Introduction

Families frequently encounter challenges as they transition home after a pediatric hospitalization. Parents and caregivers report being in a “fog” during hospitalization, which impedes processing and acting on information.1 As a result, families desire reassurance and a clear understanding of whom to call in case concerns arise after discharge.1 Addressing postdischarge barriers may reduce reutilization rates for health care services and improve other outcomes that families consider important. Postdischarge transition interventions have largely focused on children with chronic illness.2 Few interventions designed to improve the transition from hospital to home for patients and their families have focused on acute general pediatric conditions.

Postdischarge telephone calls are a common approach used to smooth hospital-to-home transitions. For adult patients, telephone calls may decrease readmission rates3 or improve the transition quality, even when reutilization rates are not changed.4 Furthermore, efforts to reduce readmission events recommend postdischarge telephone calls for at-risk adults.5,6 In pediatric populations, the utility of these telephone calls is poorly understood. Telephone calls identify postdischarge issues after pediatric hospitalization.7 However, in children hospitalized with asthma, a postdischarge telephone call coupled with enhanced education increased reutilization rates in one study8 but decreased them in another.9 Despite the lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of a postdischarge telephone call in reducing reutilization rates, telephone calls have been adopted by a large readmission reduction collaborative to prevent reutilization.10 Thus, we sought to systematically assess the effects of a postdischarge telephone call on reutilization events for urgent health care services, parental coping, and recall of important clinical information after standard pediatric discharge through a randomized clinical trial (RCT).

Methods

Trial Design, Participants, and Setting

We conducted a 2-arm RCT. Children and adolescents younger than 18 years (hereinafter referred to as children) admitted to the hospital medicine services at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), Cincinnati, Ohio, a free-standing tertiary care children’s hospital, from May 11 through October 31, 2016, were eligible. CCHMC is the only admitting pediatric facility in the metropolitan region; hospital medicine teams are responsible for all nonsubspecialty pediatric admissions. We included children with standard discharges who would not require skilled nursing after discharge. We excluded children not discharged home, living outside of the 7-county hospital primary catchment area in Ohio and Kentucky, requiring postdischarge skilled nursing services (eg, central line care), or without an English-speaking parent or caregiver (hereinafter referred to as parent). Children hospitalized at the main CCHMC campus or the 42-bed satellite community campus were eligible. The institutional review board of CCHMC approved the study. All parents provided written informed consent. The study protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Pretrial Context

The first Hospital-to-Home Outcomes (H2O) trial was a 2-arm RCT designed to assess the effectiveness of a 1-time, nurse-led transitional home visit after hospital discharge among children who would not otherwise qualify for skilled nursing visits.11 Prior focus group work1 indicated that some families prefer a telephone call to an in-person visit. We recognized that telephone calls may be more feasible and scalable given the adoption in national readmission reduction work. Thus, we adapted the in-home visit intervention to be administered by telephone. At the conclusion of enrollment of the first H2O trial, we began recruitment for this second trial.

Recruitment and Randomization

We approached participants during their hospitalization near the time of anticipated hospital discharge.12,13 Research assistants approached potentially eligible, randomly selected families using computer-generated lists. If a parent was unavailable, the research assistant continued recruitment attempts until the parent could be contacted or the child was discharged.14

Once a parent consented and completed the baseline survey, enrolled participants were randomized 1:1 to the intervention or the control group using a permuted block randomization approach with 2 stratification factors. We stratified on neighborhood poverty because transition experiences can vary for families from neighborhoods with different socioeconomic status.15 Neighborhood poverty is also associated with limited access to health care services.16,17 We used the census definition of poverty areas as census tracts where at least 20% of the population lives below the federal poverty level.18 We also stratified on state of residency (Ohio vs Kentucky) owing to potential differences in utilization patterns by state of residency.

Blinding

Participants were informed of treatment assignment at the time of randomization so that intervention families would expect a postdischarge telephone call from a nurse. Research assistants blinded to treatment assignment conducted the 14-day outcome telephone survey.

Intervention

For the telephone call intervention, we preserved key content from the in-home visit, including explicit reassurance and condition-specific education about recovery. Certified pediatric registered nurses with experience in home care called families using standardized, condition-specific templates. Telephone calls were designed to assess the patient and, when appropriate, reassure the parent of the child’s recovery. The calls reinforced discharge teaching instructions and provided families with a list of clinical red flags tailored to their child’s diagnosis that, when present, would indicate the need to seek further medical care.19 Nurses with clinical concerns contacted the discharging inpatient attending physician or primary care clinician or referred the child to seek additional care at the primary care office or emergency department (ED) (eAppendices 1-3 in Supplement 2). Telephone calls were attempted within 48 hours of discharge and must have been completed within 96 hours per study protocol.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was unplanned 30-day use of acute health care services, defined as a composite measure that included unplanned readmissions, ED visits, and urgent care visits (reutilization rate). Unplanned readmissions were identified using a previously validated definition.20 We obtained data from hospital administrative sources and augmented it with regional administrative data that captures most inpatient and ED facilities in our region.21

Secondary outcomes consisted of additional reutilization events and patient- and family-centered outcomes collected by a research assistant via 14-day telephone survey. Utilization outcomes included a 14-day measure of unplanned use of health care resources (including an unplanned visit to a physician’s office, urgent care, ED, or unplanned readmission). This outcome was considered positive if administrative data indicated or the parent reported reutilization. We also examined 30-day unplanned readmission and 30-day ED visits separately. Patient- and family-centered outcomes, chosen based on prior focus group findings and stakeholder input,1,15,22 included coping as measured by the validated Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale,23 parent-reported days until return to normalcy, and parent-reported knowledge of red flags or clinical warning signs.

Statistical Analysis

We enrolled 966 children, which would allow us to detect a 7% absolute change in readmission from a control event rate of 20% with 80% power at a type I error rate of 0.05. For all outcomes, we performed an intention-to-treat analysis, including everyone randomized except for withdrawn participants, and a per protocol analysis, including randomized participants without a major protocol violation. We defined major protocol violations as not meeting eligibility criteria after randomization, not completing the 14-day outcome telephone call within the allotted time window, and, for intervention participants, not completing the nurse call within 96 hours of discharge.

We analyzed reutilization rates using logistic regression. For parent coping (Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale scores), we used a general linear model. For return to normalcy, we used a censored Poisson model with a bound set at 15 days for those parents who reported their routines had not yet returned to normal at the 14-day outcome assessment telephone call. For recall of red flags, we used a Poisson model with the number of potential correct answers for the child’s specific condition as a covariate. All models included the variables of neighborhood poverty and state of residency. We performed analyses with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc) and Stata (version 14; StataCorp LP) software.

Results

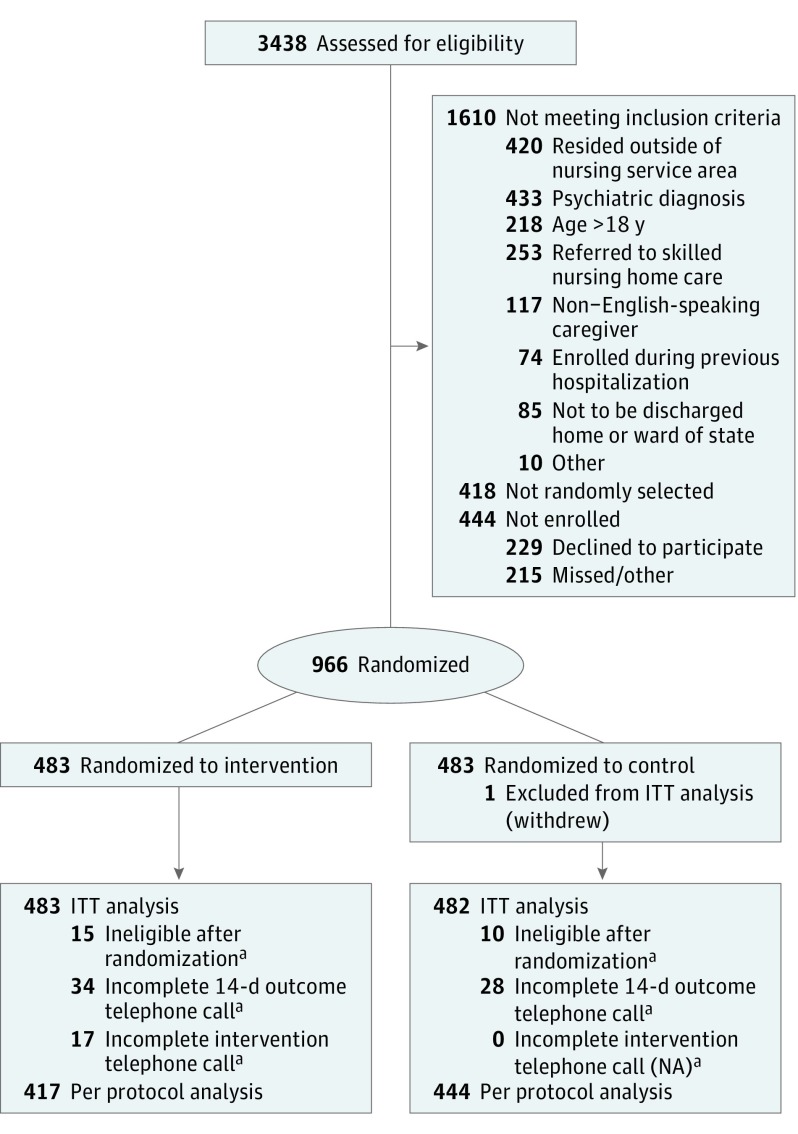

Of 3438 admissions screened as eligible, 1410 patients were approached for the study; of those, 966 (68.5% of those approached) were enrolled and randomized (505 boys [52.3%] and 461 girls [47.7%]; median [interquartile range] age, 2.4 years [0.5-7.8 years]) (Figure). We withdrew 1 participant owing to a consent issue. Age, neighborhood poverty, and state of residence were similar between groups of children who were enrolled and randomized, not enrolled, and refused participation (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Demographic characteristics were similar between the intervention and control groups (Table 1) (309 [64.0%] and 311 [64.7%], respectively, were white; 251 [52.1%] and 239 [49.9%], respectively, had public insurance). The most common primary discharge diagnosis categories25 among enrolled children included respiratory diseases (285 [29.5%]), diseases of skin and subcutaneous tissue (113 [11.7%]), and conditions originating in the perinatal period (107 [11.1%]) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Figure. Hospital-to-Home Outcomes CONSORT Flow Diagram.

ITT indicates intention to treat; NA, not applicable.

aReasons are given in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Table 1. Population Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Study Populationa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to Treat | Per Protocol | |||

| Intervention Group (n = 483) | Control Group (n = 482) | Intervention Group (n = 417) | Control Group (n = 444) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 2.4 (0.5-7.8) | 2.4 (0.5-7.8) | 2.3 (0.5-7.8) | 2.4 (0.5-7.3) |

| Female, No. (%) | 246 (50.9) | 214 (44.4) | 220 (52.8) | 194 (43.7) |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||

| White | 309 (64.0) | 311 (64.7) | 263 (63.1) | 287 (64.8) |

| Black | 117 (24.2) | 102 (21.2) | 104 (24.9) | 92 (20.8) |

| Other | 57 (11.8) | 68 (14.1) | 50 (12.0) | 64 (14.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, No. (%) | 13 (2.7) | 20 (4.2) | 9 (2.2) | 19 (4.3) |

| Insurance, No. (%) | ||||

| Private | 222 (46.1) | 231 (48.3) | 196 (47.1) | 214 (48.4) |

| Public | 251 (52.1) | 239 (49.9) | 213 (51.2) | 220 (49.8) |

| Self-pay/other | 9 (1.9) | 8 (1.7) | 7 (1.7) | 8 (1.8) |

| Reported primary care access (P3C score24), No. (%) | ||||

| Less than almost always adequate access (<75) | 87 (18.1) | 77 (16.1) | 75 (18.0) | 70 (15.9) |

| Almost always adequate access (75-99) | 205 (42.5) | 200 (41.9) | 178 (42.8) | 188 (42.7) |

| Perfect access (100) | 190 (39.4) | 200 (41.9) | 163 (39.2) | 182 (41.4) |

| Neighborhood poverty, No. (%) | ||||

| <20% | 348 (72.1) | 349 (72.4) | 302 (72.4) | 324 (73.0) |

| ≥20% | 135 (28.0) | 133 (27.6) | 115 (27.6) | 120 (27.0) |

| Home address, No. (%) | ||||

| Ohio | 382 (79.1) | 381 (79.0) | 331 (79.4) | 355 (80.0) |

| Kentucky | 101 (20.9) | 101 (21.0) | 86 (20.6) | 89 (20.1) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; P3C, Parent’s Perceptions of Primary Care.

Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Intervention

The intervention was completed within 96 hours of discharge in 442 of 483 participants (91.5%). The primary reason for an incomplete intervention telephone call was the inability to reach the family after discharge. Nurses referred 22 children (4.6%) for further care to their primary care clinician (19 children), the ED (4 children), or ongoing home care (1 child); some children were referred to more than 1 additional care source.

Follow-up

Reutilization data were obtained for all enrolled participants. Most parents (901 of 965 [93.4%]) completed the 14-day follow-up call (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Intention-to-Treat Analysis

Primary Outcome

We included 965 children in the intention-to-treat analysis after removing 1 withdrawn child. The 30-day unplanned acute reutilization rate was 15.9% (77 participants) in the intervention group and 13.1% (63 participants) in the control group (odds ratio, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.88-1.81; P = .21) (Table 2).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Utilization Outcomes.

| Outcome by Analysis | No./Total No. (%) | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||

| Intention to treat | |||

| 30-d Reutilization ratea | 77/483 (15.9) | 63/482 (13.1) | 1.26 (0.88-1.81) |

| 30-d Unplanned readmissions | 32/483 (6.6) | 27/482 (5.6) | 1.20 (0.71-2.03) |

| 30-d ED use | 35/483 (7.2) | 35/482 (7.3) | 1.00 (0.61-1.63) |

| 14-d Reutilization rate including outpatient clinic visitsb | 71/483 (14.7) | 72/482 (14.9) | 0.98 (0.69-1.40) |

| Per protocol | |||

| 30-d Reutilization ratea | 60/417 (14.4) | 56/444 (12.6) | 1.17 (0.79-1.73) |

| 30-d Unplanned readmissions | 23/417 (5.5) | 24/444 (5.4) | 1.03 (0.57-1.86) |

| 30-d ED use | 26/417 (6.2) | 30/444 (6.8) | 0.92 (0.53-1.58) |

| 14-d Reutilization rate including outpatient clinic visitsb | 54/417 (12.9) | 68/444 (15.3) | 0.82 (0.56-1.21) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; OR, odds ratio.

Primary outcome includes unplanned readmission, ED visit, and urgent care use.

Includes parent report of unplanned readmission, ED visit, urgent care use, and unscheduled outpatient appointments or administrative data indicating unplanned readmission, ED visit, and urgent care use.

Secondary Outcomes

Children randomized to the intervention compared with the control arm had similar 30-day rates of unplanned readmission (32 [6.6%] for intervention vs 27 [5.6%] for control) and ED use (35 [7.2%] for intervention and 35 [7.3%] for control). They also had similar 14-day reutilization rates, including unplanned physician’s office visits (71 [14.7%] for intervention vs 72 [14.9%] for control) (Table 2). Most children visited their primary care physicians in the 2 weeks after hospitalization (including planned and unplanned visits: 337 of 458 [73.6%] in the intervention group and 341 of 460 [74.1%] in the control group). Coping scores (measured by the Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale) and the number of days until return to normalcy were similar in the intervention and control groups. Intervention parents recalled significantly more red flags than those in the control group (mean, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.7-2.0] vs 1.5 [95% CI, 1.4-1.6]; ratio of intervention to control, 1.2 [95% CI, 1.1-1.3]) (Table 3). In total, 124 of 458 parents in the intervention group (27.1%) accurately recalled 3 or more red flags compared with 88 of 460 control parents (19.1%).

Table 3. Secondary Patient- and Family-Centered Outcomes.

| Outcome by Analysis | Mean (95% CI) | Difference or Ratio of Means (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||

| Intention to treata | |||

| PDCDS scoreb | 14.3 (12.8 to 15.8) | 15.2 (13.7 to 16.7) | −0.9 (−2.7 to 0.9) |

| Time until return to normalcy, dc | 3.9 (3.5 to 4.2) | 4.2 (3.8 to 4.6) | 0.92 (0.81 to 1.06) |

| No. of red flags recalledd,e | 1.8 (1.7 to 2.0) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) |

| Per protocolf | |||

| PDCDS scoreb | 13.3 (11.8 to 14.9) | 14.8 (13.3 to 16.3) | −1.4 (−3.2 to 0.3) |

| Time until return to normalcy, dc | 3.7 (3.3 to 4.1) | 4.2 (3.8 to 4.6) | 0.88 (0.76 to 1.00) |

| No. of red flags recallede | 1.9 (1.7 to 2.0) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) |

Abbreviation: PDCDS, Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale.

Includes 457 intervention and 460 control participants (owing to failure to complete the 14-day telephone call), unless otherwise indicated.

Score ranges from 0 to 100, with high scores indicating more difficulty coping. Marginal means and differences in the PDCDS score are obtained from linear regression models, adjusted for stratification factors (neighborhood poverty and state). The 95% CIs for the difference include the null-hypothesized value of 0.

Marginal means and ratio for time until return to normalcy are obtained from censored Poisson regression models with a bound at 15 days for those parents who had not returned to normal at the 14-day call, adjusted for stratification factors. The 95% CIs for the ratio include the null-hypothesized value of 1.

Includes 458 intervention participants.

Marginal means and ratio for number of red flags recalled are obtained from Poisson regression models, adjusted for stratification factors and the number of potentially correct answers for the patient’s condition. The 95% CIs for the ratio exclude the null-hypothesized value of 1.

Includes 417 intervention and 444 control participants.

Per Protocol Analysis

For the per protocol analysis, we included 417 children in the intervention group and 444 children in the control group. Child-level reasons for exclusions (totals from intervention and control arms combined) included ineligibility after randomization (n = 25), failure to complete the 14-day outcome assessment telephone call (n = 62), and failure to complete the intervention (n = 17) (Figure). There are no comparable control exclusions for the 17 intervention children excluded owing to intervention nonadherence. Protocol-level exclusions are displayed in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Outcomes

The 30-day reutilization rates for health care services were similar in the 2 groups (odds ratio, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.79-1.73) (Table 2). Analyses of secondary outcomes in the per protocol population were similar to those in the intention-to-treat population. Parents in the intervention group recalled significantly more red flags at 14 days (mean, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.7-2.0] in intervention vs 1.5 [95% CI, 1.4-1.6] in control; ratio of intervention to control, 1.2 [95% CI, 1.1-1.4]) (Tables 2 and 3). Of note, parents in the intervention group reported fewer days until returning to a normal routine compared with parents in the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant (3.7 [95% CI, 3.3-4.1] days vs 4.2 [95% CI, 3.8-4.6] days; ratio of intervention to control, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.76-1.00]).

Discussion

In an RCT of children admitted to general pediatric hospital medicine teams, a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after discharge did not affect reutilization rates for health care services; however, parents in the intervention recalled significantly more clinical warning signs or red flags at 14 days. Our high adherence rate in the intervention group indicates excellent acceptability of a postdischarge telephone call from a nurse.

Prior studies of postdischarge transition telephone calls have often been limited by observational design or evaluation in combination with other interventions without the ability to evaluate the effectiveness of the telephone call separately.26 Our current work, designed as an RCT of a single intervention, was intended to overcome this literature gap for the general pediatric population. Our results do not indicate that a postdischarge telephone call decreases reutilization rates for standard discharges. A small prior observational study of postdischarge telephone calls in a general pediatric population demonstrated that postdischarge telephone calls could identify ongoing challenges, although such telephone calls were not significantly associated with change in reutilization rates.27

The results of both H2O trials have interesting similarities and differences (Table 4).11 The first H2O trial compared a postdischarge in-home nurse visit with standard discharge. In both trials, children randomized to the intervention groups had higher odds of unplanned 30-day use of health services than the control groups (1.33 in the first H2O trial; 1.26 in the present H2O trial). In the first H2O trial, this difference was statistically significant; however, in the present work, the higher odds are not significant. In addition to differences associated with administration of the intervention by telephone vs in person, there are differences in study design. The first H2O trial included patients discharged from hospital medicine, neurology, or neurosurgical teams. In the present trial, we only recruited patients from the hospital medicine services because neurology teams were trialing postdischarge telephone calls outside this study. We recruited from a broader service area in the present trial compared with the first H2O trial, including our community hospital site and children who lived in another state (Kentucky) within our hospital’s primary catchment area. Children from Kentucky were excluded in the first trial owing to nursing licensing restrictions on in-home visits. Another difference between the 2 trials relates to postdischarge coping. Parents in the control group in this trial had much less difficulty coping after discharge than parents in the control group of the first H2O trial. The differences in postdischarge coping between the 2 trials may reflect secular trends at our hospital or a difference in patient population. Despite these differences, the 2 interventions (ie, home visit and telephone call) yielded similar point estimates of higher odds of reutilization at 30 days. Together, these trials highlight that postdischarge interventions failed to prevent urgent health care reutilization after standard pediatric discharge.

Table 4. Comparisons of H2O Trials.

| Characteristic | First H2O Trial11 | Second (Present) H2O Trial |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | One-time postdischarge in-home nurse visit, within 96 h | One-time postdischarge telephone call, within 96 h |

| Population | Children with standard discharge by hospital medical teams or neurosciences team at main CCHMC campus | Children with standard discharge by hospital medical teams at main CCHMC campus or satellite campus |

| Recruitment area | Children living in hospital primary service area in the state of Ohio | Children living in hospital primary service area in the states of Ohio and Kentucky |

| Refused to enroll, % | 35 | 16.2 |

| Randomized to intervention, % | 87 | 91.5 |

| 30-d Reutilization rate, % | ||

| Intervention group | 17.8a | 15.9 |

| Control group | 14.0a | 13.1 |

| PDCDS score, meanb | ||

| Intervention group | 20.4 | 14.3 |

| Control group | 21.2 | 15.2 |

| Time until normalcy, mean, d | ||

| Intervention group | 4.2 | 3.9 |

| Control group | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| No. of red flags recalled, mean | ||

| Intervention group | 1.9a | 1.8a |

| Control group | 1.6a | 1.5a |

Abbreviations: CCHMC, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; H2O, Hospital-to-Home Outcome; PDCDS, Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale.

Statistically significantly different in intention-to-treat analysis.

Score ranges from 0 to 100, with high scores indicating more difficulty coping.

We designed our intervention to address challenges that families identified as postdischarge concerns in the prior focus groups.1 Families desire information on postdischarge care, including information on who to call if problems arise. Families desire reassurance when their child is recovering appropriately. We designed the intervention to provide these elements to families, assuming that addressing these barriers and desires would subsequently reduce reutilization rates. Although this family-centered design would, in theory, decrease difficulty coping and speed return to normal routines, these phenomena were not observed in either H2O study. Instead, any potential positive effects of reassessment and reassurance on postdischarge coping may have been negated by other intervention effects. Postdischarge interventions initiated from the discharging hospital may enhance access back to the ED instead of the primary care office. The list of red flags or warning signs provided to patients in the intervention could heighten vigilance, disrupt a sense of normalcy, or prompt some families to seek care beyond what they would have done without these lists.

In both H2O trials, parents in the intervention arm recalled more red flags than parents in the control group. Although the absolute effect size of this difference is small, at 2 weeks post discharge 27.1% of parents randomized to a telephone call accurately recalled 3 or more red flags compared with 19.1% of control parents. The clinical relevance of retaining more red flags at 2 weeks is unclear. Among children hospitalized with asthma, a parent’s ability to demonstrate more asthma knowledge was associated with an increased risk of readmission.28 Nevertheless, parents in the prior postdischarge focus group stressed the need for clear warning signs after discharge. They reported that the “fog” of a hospitalization impedes retention of information when preparing for discharge and reentering their home environment.1 Parents’ ability to recall these warning signs indicates the closing of a caregiver-perceived transition gap. A nurse-led encounter, by telephone or in the home, increases a parent’s ability to remember warning signs 2 weeks after discharge and may be leveraged as an effective method for delivering education.

As a potential means to enhance education, feasibility and acceptability of interventions are important considerations. The nurse-led postdischarge telephone call has a high level of acceptability. Only 229 of 1410 families approached for enrollment (16.2%) refused study participation (Figure). Comparatively, 34.6% refused enrollment in the first H2O in-home nurse-visit RCT.11,14 In addition, the intervention completion rate was greater in the telephone call trial, with intervention completion in 91.5% compared with intervention completion in 87.2% of families in the first H2O trial with in-home visits. In this trial, with accounting for the lower refusal rates as well as the higher intervention completion rates, postdischarge telephone calls seemed more acceptable to families than in-home nurse visits.

Our inability to decrease postdischarge reutilization rates for acute health care after a nontargeted intervention (ie, not focused solely on a high-risk population) is important from a health policy standpoint. In the previous focus groups with families,1 parents did not identify prevention of reutilization as a concern during the postdischarge transition period. These interventions, designed to address family-perceived barriers to transitions through a visit or a telephone call, did not decrease reutilization rates, perhaps because we do not fully understand what drives the use of health care services in the postdischarge period. Therefore, hospital quality readmission metrics may not be well aligned with family desires for improved postdischarge transitions.

Limitations

This trial should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, the trial was performed in a real-world clinical setting. Throughout the trial, ongoing efforts sought to enhance the readability of discharge instructions provided to families before leaving the hospital, including signs and symptoms to seek additional care.29 These improvements would have affected patients in the intervention and control arms equally. The differences in recalling red flags seems particularly notable because controls received clear messages regarding warning signs during this trial through standard discharge processes. Second, although research assistants making outcome telephone calls were blinded to random assignment, nurses providing the intervention and families were not blinded. Intervention families may have behaved differently because they knew they would be receiving a postdischarge telephone call. Finally, our control reutilization rate was 13.1%, but our power calculations were based on 20% because we did not yet have the results of the first H2O trial during our design of this trial. Given that the telephone call and the in-home visit findings had point estimates in the same direction (toward increased reutilization rates), lack of power likely does not explain not finding a significant decrease in reutilization rates.

Conclusions

A 1-time nurse-led telephone call did not result in a decrease in urgent 30-day reutilization events in children admitted to a general pediatric hospital service with standard discharges. However, parents who received the telephone call were better able to recall clinical red flags or warning signs 2 weeks after discharge.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Characteristics of Children Enrolled, not Enrolled, and Refused

eTable 2. Primary Discharge Diagnosis Category

eTable 3. Reasons for Per Protocol Exclusions by Type of Event (Protocol-Level Exclusions)

eAppendix 1. Bronchiolitis Nurse Telephone Call Guide

eAppendix 2. General Diagnoses Nurse Telephone Call Guide

eAppendix 3. Red Flag Templates

References

- 1.Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. ; H2O Study Group . The family perspective on hospital to home transitions: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):-. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):251-260. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong FK, Chow SK, Chan TM, Tam SK. Comparison of effects between home visits with telephone calls and telephone calls only for transitional discharge support: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2014;43(1):91-97. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soong C, Kurabi B, Wells D, et al. Do post discharge phone calls improve care transitions? a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams MV, Coleman E. BOOSTing the hospital discharge. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):209-210. doi: 10.1002/jhm.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Society of Hospital Medicine Project BOOST: Better Outcomes for Older Adults Through Safe Transitions: implementation guide to improve care transitions. http://tools.hospitalmedicine.org/Implementation/Workbook_for_Improvement.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2017.

- 7.Wu S, Tyler A, Logsdon T, et al. A quality improvement collaborative to improve the discharge process for hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20143604. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis AM, Benson M, Cooney D, Spruell B, Orelian J. A matched-cohort evaluation of a bedside asthma intervention for patients hospitalized at a large urban children’s hospital. J Urban Health. 2011;88(suppl 1):49-60. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9517-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng DK, Chow PY, Lai WP, Chan KC, And BL, So HY. Effect of a structured asthma education program on hospitalized asthmatic children: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Int. 2006;48(2):158-162. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2006.02185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Children’s Hospitals’ Solutions for Patient Safety SPS prevention bundles: readmissions. http://www.solutionsforpatientsafety.org/wp-content/uploads/SPS-Prevention-Bundles.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 11.Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley H, et al. Post-discharge nurse home visits and reutilization: the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) Trial [published online June 22, 2018]. Pediatrics. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White CM, Statile AM, White DL, et al. Using quality improvement to optimise paediatric discharge efficiency. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428-436. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tubbs-Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Simmons JM, et al. ; H2O Study Group . Testing a post-discharge nurse-led transitional home visit in acute care pediatrics: the Hospital-to-Home Outcomes (H2O) study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(4):915-925. doi: 10.1111/jan.12882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauers-Ford HS, Gold JM, Statile AM, et al. ; H2O Study Group . Improving recruitment and retention rates in a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):e20162770. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AF, Solan LG, Brunswick SA, et al. Socioeconomic status influences the toll paediatric hospitalisations take on families: a qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(4):304-311. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auger KA, Kahn RS, Simmons JM, et al. Using address information to identify hardships reported by families of children hospitalized with asthma. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(1):79-87. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AF, Huang B, Simmons JM, et al. Role of financial and social hardships in asthma racial disparities. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):431-439. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United States Census Bureau Living in poverty areas. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2014/comm/cb14-123_poverty_areas.html. Published June 30, 2014. Accessed May 6, 2017.

- 19.Pickler R, Wade-Murphy S, Gold J, et al. ; H2O Study Group . A nurse transitional home visit following pediatric hospitalizations. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46(12):642-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auger KA, Mueller EL, Weinberg SH, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-112.e1, 2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Health Collaborative Healthbridge analytics. http://healthcollab.org/hbanalytics/. Accessed August 11, 2017.

- 22.Sauers-Ford HS, Simmons JM, Shah SS; H2O Study Team . Strategies to engage stakeholders in research to improve acute care delivery. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):123-125. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss M, Johnson NL, Malin S, Jerofke T, Lang C, Sherburne E. Readiness for discharge in parents of hospitalized children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2008;23(4):282-295. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seid M, Varni JW, Bermudez LO, et al. Parents’ perceptions of primary care: measuring parents’ experiences of pediatric primary care quality. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):264-270. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Chronic condition indicator. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Accessed March 17, 2017.

- 26.Jayakody A, Bryant J, Carey M, Hobden B, Dodd N, Sanson-Fisher R. Effectiveness of interventions utilising telephone follow up in reducing hospital readmission within 30 days for individuals with chronic disease: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):403. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1650-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heath J, Dancel R, Stephens JR. Postdischarge phone calls after pediatric hospitalization: an observational study. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(5):241-248. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2014-0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auger KA, Kahn RS, Davis MM, Simmons JM. Pediatric asthma readmission: asthma knowledge is not enough? J Pediatr. 2015;166(1):101-108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unaka N, Statile A, Jerardi K, et al. Improving the readability of pediatric hospital medicine discharge instructions. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):551-557. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Characteristics of Children Enrolled, not Enrolled, and Refused

eTable 2. Primary Discharge Diagnosis Category

eTable 3. Reasons for Per Protocol Exclusions by Type of Event (Protocol-Level Exclusions)

eAppendix 1. Bronchiolitis Nurse Telephone Call Guide

eAppendix 2. General Diagnoses Nurse Telephone Call Guide

eAppendix 3. Red Flag Templates