Abstract

This population-based study examines the changes in enrollment in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program since institution of the Affordable Care Act.

Increases in health insurance coverage after 2013 varied by state-level policy choices under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).1,2 Larger increases were observed in states adopting the Medicaid expansion to adults,1,2 and Medicaid enrollment grew more in states using state-based marketplaces.2 Another policy dimension on which states differed was marketplace authority to enroll publicly eligible applicants in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The ACA’s “no wrong door” policy requires all marketplaces to assess whether applicants are eligible for Medicaid/CHIP, but only requires state-based marketplaces to enroll publicly eligible applicants. States relying on federally facilitated marketplaces (including those with state-federal partnership or federal information technology support) can opt to defer final enrollment authority to state-level Medicaid/CHIP agencies.3 Take-up of public coverage in these states could be dampened if Medicaid/CHIP-eligible applicants face process delays, process errors, or reversals in applicants’ assessed eligibility. We consider the role of marketplace policy in early years of the adult Medicaid expansion, comparing changes in the probability that Medicaid/CHIP-eligible children and parents living in expansion states enrolled in public coverage across marketplace structure and enrollment authority.

Methods

We used data from the American Community Survey between 2013 and 2015 for children (age, 0-18 years) and parents living in states that adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion.4 Samples were restricted to nondisabled US citizens who were simulated to be eligible for Medicaid/CHIP.5 We used linear-probability models to measure percentage point changes in public coverage over time and compared those changes across different state-level marketplace policies (state-based, federally facilitated with authority to enroll Medicaid/CHIP-eligible applicants, and federally facilitated without enrollment authority) for 3 policy-relevant groups: Medicaid/CHIP-eligible children below 400% of the federal poverty level, parents below 400% of the federal poverty level who were already Medicaid eligible prior to the ACA, and parents at 0% to 138% of the federal poverty level who became Medicaid-eligible via the ACA expansion to adults. All models included state-fixed effects, controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, language, educational level, employment, marital status, and family structure, and cluster at the state-level for SEs. Public coverage was measured as having any public coverage during the year. The study was approved by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. All results reported were significant at the P < .05 level or higher. Analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 15 (StataCorp).

Results

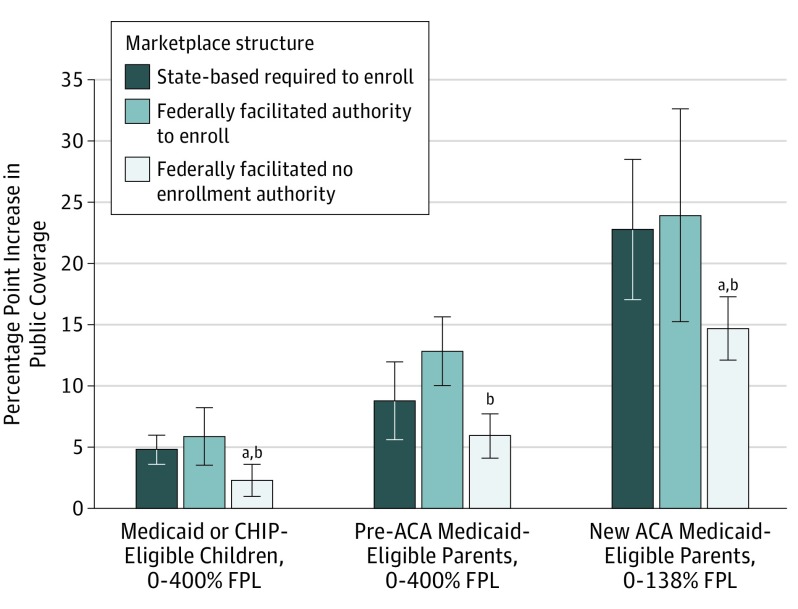

Take-up of public coverage increased for all sample groups between 2013 and 2015 (Figure). Magnitude varied across eligibility groups and within eligibility groups by marketplace structure. Gains were largest among newly eligible parents, but take-up also increased among pre-ACA–eligible parents and children. For example, in states running state-based marketplaces, public coverage increased by 22.8 percentage points (95% CI, 17.1-28.5) among newly eligible parents, by 8.8 percentage points (95% CI, 5.7-12.0) for previously eligible parents, and 4.8 percentage points (95% CI, 3.6-6.0), for previously eligible children.

Figure. Changes in Public Coverage by Marketplace Policy; Medicaid- or CHIP-Eligible Children and Parents in Expansion States, American Community Survey, 2013-20154.

Linear probability estimates of changes in public coverage obtained using sample weights. Percentage-point changes are obtained from the coefficient estimates of the following variables: year 2015 indicator and an interaction between year 2015 and an indicator for each marketplace structure. The model controls for state-fixed effects, age, race, ethnicity, sex, language, educational level, employment, marital status, and family structure. Percentage point increases between 2013 and 2015 are significantly different from zero at the 5% level for all samples and all marketplace structures. Bars indicate 95% CIs calculated from SEs cluster-corrected at the state level. ACA indicates Affordable Care Act; CHIP, Children's Health Insurance Program; FPL, federal poverty level.

aA significant within-sample difference at the 5% level between state-based and both types of federally facilitated marketplaces.

bA significant within-sample difference at the 5% level between federally facilitated marketplaces with and without enrollment authority.

Marketplace policy results indicate that increases in public coverage for all groups were smallest in states with no marketplace authority to enroll Medicaid/CHIP-eligible applicants. For example, among newly eligible parents, the coverage gain was 14.7 percentage points (95% CI, 12.1-17.1) in states with no enrollment authority compared with 22.8 percentage points (95% CI, 17.1-28.5) in states with state-based marketplaces and 23.9 percentage points (95% CI, 15.2-32.6) in states with federally facilitated marketplaces that enrolled applicants. There were no significant differences between state-based and federally facilitated marketplaces with enrollment authority.

Discussion

Previous work found that states running state-based marketplaces had greater increases in Medicaid/CHIP enrollment than states running federally facilitated marketplaces.2 Limitations of our research include the potential for measurement error in simulated eligibility for Medicaid/CHIP, misreported insurance coverage in ACS, and inability to identify unmeasured factors that occurred contemporaneously with implementation of ACA policies studied.

Our results suggest that streamlining Medicaid/CHIP enrollment may have played a substantial role in increased take-up of public coverage. Increases were larger in states where Medicaid/CHIP enrollment occurred within the marketplace, regardless of whether the marketplace was state-based or federally facilitated. Furthermore, once we account for marketplace enrollment authority, there were no longer differences between state-based marketplaces and federally facilitated marketplaces with enrollment authority. The findings of this study highlight program coordination as a potential tool for child health policy, by reaching the eligible uninsured and increasing joint parent-child Medicaid coverage.5,6

References

- 1.Kenney G, Haley J, Pan C, Lynch V, Buettgens M. Medicaid/CHIP participation rates rose among children and parents in 2015. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/90346/2001264-medicaid-chip-pariticipation-rates-rose-among-children-and-parents-in-2015_1.pdf. Published May 2017. Accessed December 14, 2017.

- 2.Rosenbaum S, Schmucker S, Rothenberg S, Gunsalus R Streamlining Medicaid enrollment: the role of health insurance marketplaces and the impact of state policies. Commonwealth Fund Issue Brief. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/mar/medicaid-enrollment-marketplaces. Published March 2016. Accessed December 14, 2017.

- 3.Medicaid Program Eligibility Changes under the Affordable Care Act of 2010, 77 Fed. Reg. 57, 17144 (March 23, 2012) (codified at 42 CFR pts 431, 435, and 457). https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-03-23/pdf/2012-6560.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2017. [PubMed]

- 4.United States Census Bureau American Community Survey Design and Methodology (January 2014). Version 2. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/methodology/design_and_methodology/acs_design_methodology_report_2014.pdf. Published January 30, 2014. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- 5.Hudson JL, Moriya AS. Medicaid expansion for adults had measurable “Welcome Mat” effects on their children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1643-1651. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkataramani M, Pollack CE, Roberts ET. Spillover effects of adult Medicaid expansions on children’s use of preventive services. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20170953. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]