Abstract

This study assesses the association of infective endocarditis with mortality from 1999 to 2016 among people who inject drugs in the United States.

Deaths from opioid abuse have increased markedly among an otherwise young and healthy population.1 Approximately a million people used heroin in the United States in 2016, 2 times more than the number who used heroin in the entire period between 2002 and 2013.2 Because people who inject drugs (PWID) are at risk for bacteremia, we hypothesized that their mortality from infective endocarditis has increased.

Methods

Using the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Multiple Cause-of-Death database, we analyzed US death certificates, which contain 1 to 20 underlying causes of death, between 1999 and 2016. We included all infective endocarditis deaths in people aged 15 to 64 years using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes I33, I38, and B37.6, with diagnoses associated with intravenous drug abuse, psychoactive substance abuse, or acute hepatitis C (ICD10 codes T40.0-T40.4, T40.6, F11, F13-F16, F19, X42, and B17.1) in the multiple causes of death field. Comparisons were performed using χ2 test.

The University Hospitals and Case Western Reserve University waived institutional review board permission because the data are publicly available. Also, informed consent was not applicable because all patient information was deidentified and anonymous.

Results

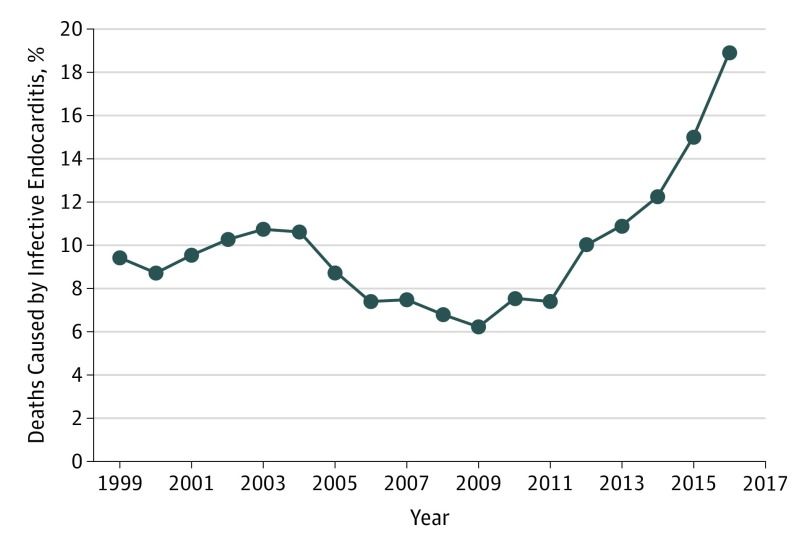

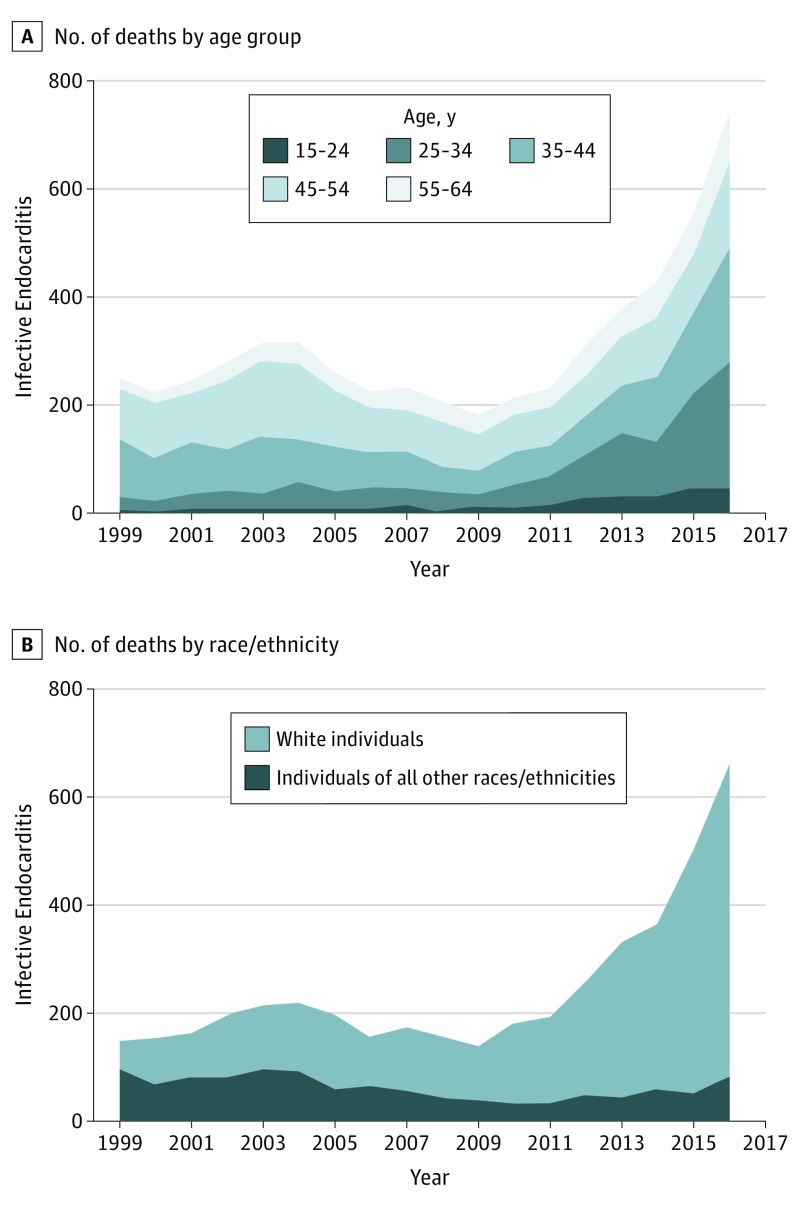

Of 55 212 deaths from infective endocarditis, 5607 (10.2%) occurred in PWID. Infective endocarditis deaths among PWID increased 3-fold from 1999 (n = 249) to 2016 (n = 746) (Figure 1), compared with a 1.5-fold increase in deaths caused by infective endocarditis in general. The proportion of infective endocarditis deaths in PWID increased from 249 of 2636 patients (9.4%) in 1999 to 746 of 3944 (18.9%) in 2016 (P < .001). Among PWID who died of infective endocarditis, the proportion of patients younger than 35 years rose from 12.4% (n = 31/249) in 1999 to 37.4% (n = 279/746) in 2016 (P < .001; Figure 2), and the proportion of white individuals rose from 60.2% (n = 150/249) in 1999 to 88.9% (n = 663/746) in 2016 (P < .001). The underlying cause of death was infective endocarditis (n = 1319; 23.5%), drug use (n = 3037; 54.2%), septicemia (ICD10 code A41; n = 86; 1.5%), stroke/intracranial hemorrhage (ICD10 codes I60-I64; n = 125; 2.2%), and ischemic heart disease (ICD10 codes I20-I25; n = 121; 2.2%).

Figure 1. Rising Infective Endocarditis Mortality Among People Who Inject Drugs (1999-2016).

Figure 2. Infective Endocarditis Mortality Among People Who Inject Drugs by Age Group and Race (1999-2016).

Discussion

The opioid crisis has created a national public health emergency. Although PWID die most commonly of anoxic brain injury,3 infective endocarditis is a potentially fatal complication caused by contaminated syringes.4 Even in nonfatal cases, infective endocarditis can result in sepsis, the need for valve replacement, and heart failure, leading to high morbidity-mortality health care expenditure.5 In this study, we demonstrate a disproportionate increase in infective endocarditis deaths among young white PWID from 1999 to 2016 without a corresponding rise in all-cause infective endocarditis mortality. While we only address fatal cases, infective endocarditis hospitalizations among PWID have also increased.6

Although our findings appear linked to the opioid crisis, there are other putative explanations. For example, more virulent and resistant microorganisms may have increased lethality of infective endocarditis in PWID. Also, previously treated patients who had infective endocarditis who subsequently died from overdose may confound our findings. Lastly, because death certificates may lack accuracy in cause of death attribution, direct causality of infective endocarditis deaths to opioid use cannot be ascertained.

Taken together, our findings should prompt clinicians to be vigilant when treating PWID with fevers and to use a low threshold to initiate antibiotic therapy to mitigate further infective endocarditis fatalities.

References

- 1.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(5051):1445-1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahrnsbrak R, Bose J, Hedden SL, Lipar RN, Park-Lee E, Tice P Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2016. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.htm#fig15. Published September 2017. Accessed May 3, 2018.

- 3.Darke S, Zador D. Fatal heroin ‘overdose’: a review. Addiction. 1996;91(12):1765-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathew J, Addai T, Anand A, Morrobel A, Maheshwari P, Freels S. Clinical features, site of involvement, bacteriologic findings, and outcome of infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(15):1641-1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischauer AT, Ruhl L, Rhea S, Barnes E. Hospitalizations for endocarditis and associated health care costs among persons with diagnosed drug dependence—North Carolina, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(22):569-573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deo SV, Raza S, Kalra A, et al. Admissions for infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(14):1596-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]