Key Points

Question

Is first-trimester first abortion associated with an increase in women’s risk of first-time antidepressant use?

Findings

In this cohort study of 396 397 women born in Denmark between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 1994, women who had a first abortion had a higher risk of first-time antidepressant use compared with women who did not have an abortion. However, for women who had a first abortion, the risk was the same in the year before and the year after the abortion and decreased as time from the abortion increased.

Meaning

Having a first abortion is not associated with an increase in a woman’s risk of first-time antidepressant use.

Abstract

Importance

The repercussions of abortion for mental health have been used to justify state policies that limit access to abortion in the United States. Much earlier research has relied on self-report of abortion or mental health conditions or on convenience samples. This study uses data that rely on neither.

Objective

To examine whether first-trimester first abortion or first childbirth is associated with an increase in women’s initiation of a first-time prescription for an antidepressant.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study linked data and identified a cohort of women from Danish population registries who were born in Denmark between January 1, 1980, and December 30, 1994. Overall, 396 397 women were included in this study; of these women, 30 834 had a first-trimester first abortion and 85 592 had a first childbirth.

Main Outcomes and Measure

First-time antidepressant prescription redemptions were determined and used as indication of an episode of depression or anxiety, and incident rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated comparing women who had an abortion vs women who did not have an abortion and women who had a childbirth vs women who did not have a childbirth.

Results

Of 396 397 women whose data were analyzed, 17 294 (4.4%) had a record of at least 1 first-trimester abortion and no children, 72 052 (18.2%) had at least 1 childbirth and no abortions, 13 540 (3.4%) had at least 1 abortion and 1 childbirth, and 293 511 (74.1%) had neither an abortion nor a childbirth. A total of 59 465 (15.0%) had a record of first antidepressant use. In the basic and fully adjusted models, relative to women who had not had an abortion, women who had a first abortion had a higher risk of first-time antidepressant use. However, the fully adjusted IRRs that compared women who had an abortion with women who did not have an abortion were not statistically different in the year before the abortion (IRR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.38-1.54) and the year after the abortion (IRR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.45-1.62) (P = .10) and decreased as time from the abortion increased (1-5 years: IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.19-1.29; >5 years: IRR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.05-1.18). The fully adjusted IRRs that compared women who gave birth with women who did not give birth were lower in the year before childbirth (IRR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.43-0.50) compared with the year after childbirth (IRR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.88-0.98) (P < .001) and increased as time from the childbirth increased (1-5 years: IRR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.47-1.56; >5 years: IRR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.91-2.09). Across all women in the sample, the strongest risk factors associated with antidepressant use in the fully adjusted model were having a previous psychiatric contact (IRR, 3.70; 95% CI, 3.62-3.78), having previously obtained an antianxiety medication (IRR, 3.03; 95% CI, 2.99-3.10), and having previously obtained antipsychotic medication (IRR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.81-1.96).

Conclusions and Relevance

Women who have abortions are more likely to use antidepressants compared with women who do not have abortions. However, additional aforementioned findings from this study support the conclusion that increased use of antidepressants is not attributable to having had an abortion but to differences in risk factors for depression. Thus, policies based on the notion that abortion harms women's mental health may be misinformed.

This study of a large cohort of Danish women examines the association between first-trimester first abortion or first childbirth with risk of a first-time prescription for an antidepressant.

Introduction

The purported mental health effects of having an abortion are used to justify state policies that limit access to abortion in the United States despite studies and reviews that have failed to show that having an abortion has a causal effect on mental health.1,2,3,4,5,6 Proponents of the view that having an abortion harms mental health cite research showing a greater prevalence of depression among women who have had an abortion compared with women who have not.7 One shortcoming of many studies in the field is their reliance on self-report of both abortion and mental health problems, which is subject to both faulty memory and social desirability in reporting.8,9

Two recent studies used the Danish population registries to examine the association between abortion and psychiatric admission.3,4 They found no increase in such admissions after having a first abortion, whereas psychiatric admissions increased after first childbirth. Psychiatric admissions to secondary and tertiary health care centers reflect severe disorders; thus, the generalizability of such findings to milder mental health epiosdes (eg, depression) is limited. Mild to moderate mental health episodes, which are more common than severe mental health episodes and are generally treated in primary care settings, are the focus of this study.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine the association between first abortion and first time obtaining antidepressant medication, which is an indicator of an episode of depression or anxiety,10 and compare it with the association between childbirth and first antidepressant use. By examining first antidepressant use as our outcome, we gain a broader understanding of the association between abortion and subsequent mental health conditions. In addition, we examine the risk of having vs not having a first abortion on first time antidepressant use over time to test whether the risk of depression after having a first abortion varies over time. Finally, we examine models adjusted for age and calendar year and models that also adjust for other factors shown to confound the association between abortion and subsequent mental health conditions.5,11

Methods

Study Population

We used data for all women born in Denmark between January 1, 1980, and December 30, 1994, who did not die or emigrate from Denmark before their 18th birthday or study entry. Follow-up time started on the woman’s 18th birthday or January 1, 2000, whichever came last. Follow-up ended at the date of first obtaining an antidepressant, date of emigration from Denmark, date of death, or December 31, 2012, whichever came first. Women who had an antidepressant prescribed before the study period began were excluded from the study. In addition, of the remaining women, those who had a childbirth or abortion before age 18 were also excluded from this study, since women who obtain abortions before this age require consent from their parents or legal guardians. This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Maryland Internal Review Board; the Danish Protection Agency; the Danish National Board of Health; and Statistics Denmark. All data were deidentified.

Measures

Outcome: Antidepressant Use

The main outcome was a first prescription for antidepressants, which earlier research has shown is an indicator of mild to moderate depression or anxiety.10,12 Redemption of prescriptions for antidepressant medication was defined through the Danish National Prescription Registry, which contains records of all prescriptions for drugs dispensed from Danish pharmacies after 1994.13 The relevant information for this study was the World Health Organizaton standardized Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code (N06A), the generic name, the package size, the formulation, the quantity dispensed, and the date of transaction of each drug.

Variables and Covariates

First-trimester first abortions were identified through the Danish National Patient Registry,14 which has information on treatment at all medical hospitals in Denmark, including dates and codes for inpatient admissions since 1970 and outpatient contacts since 1995. This registry includes information on all induced abortions performed in Denmark except those performed at private clinics in 2005 or later (55 of 15 103 total abortions in 2005; 0.4%).15 Induced first-trimester abortions were identified as the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), code O04. This variable was a time-varying factor and took on the values of abortion vs no abortion.

Using the Danish Civil Registry System,16 we identified whether and when women had a first childbirth during the study period. This variable was a time-varying factor and took on the values of childbirth vs no childbirth.

We included the time-varying covariates of age and calendar year, preexisting mental health disorders, parental mental health disorders, and physical health and the time-invariant covariate of socioeconomic status at age 15 years. Age, calendar year, socioeconomic status, preexisting mental health disorders, and parental mental health disorders have been found to be associated with having an abortion, mental health disorders after pregnancy, or antidepressant use.3,5,11,17 The Charlson Comorbidity Index was used as an indicator for physical health, and poor physical health is associated with depression.18

Age and the calendar year were drawn from the Danish Civil Registry System.16 Using the Integrated Database for Longitudinal Labor Market Research,19 we identified each parent’s level of education at the woman’s 15th birthday as a measure of women’s socioeconomic status at age 15 years. In the Danish registries, there are 10 possible levels of education, ranging from completing 8 to 10 grade levels up to completing a PhD. A level in the middle titled “medium cycle higher education,” which is typical of professions such as social worker, nurse, or police officer, was used as the reference category.

We included 3 measures to assess the woman’s mental health history: (1) prior inpatient or outpatient psychiatric admission (all ICD-10 codes in chapter F, mental and behavioral disorders), (2) prior use of antipsychotic medications (ATC code N05A), and (3) prior use of antianxiety medications (ATC codes N05C, N05BA, and N0AE01). The first was identified from the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry,20 and the latter 2 were identified from the Danish National Prescription Registry.14

We identified whether either parent of the woman had a psychiatric inpatient or outpatient admission by using the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry.20

We computed a Charlson Comorbidity Index,21,22 an indicator of somatic disease burden, for each woman by using the Danish National Patient Registry.14 The Charlson Comorbidity Index consists of 19 severe, chronic diseases, each assigned a weight from 1 to 6 corresponding to the relative risk of mortality from the disease. Total possible scores range from 0 to 37. The Charlson Comorbidity Index is calculated by summing all the weights. We coded women into a score of 0, a score of 1, and a score of 2 or more on this index.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted 2 sets of analyses. First, survival analysis was used to examine the risk of redeeming antidepressant medication associated with a first abortion (vs no abortion) and a first childbirth (vs no childbirth). For these analyses, we examined incidence rate ratios (IRRs) associated with the time-varying factors of abortion (vs no abortion) and childbirth (vs no childbirth), similar to other studies in this area.3,4,23 Furthermore, to examine whether the risk of first antidepressant use associated with abortion or childbirth changed from before to after the exposure and as time since each exposure increased, we examined a basic model that estimated the risk in the year before each exposure, the year after each exposure, more than 1 to 5 years after each exposure, and more than 5 years after each exposure relative to not being exposed (ie, no abortion for the abortion exposure and no childbirth for the childbirth exposure), and we included only the time-varying covariates of age and cohort (calendar year). In another fully adjusted model, we added the time-varying covariates of prior psychiatric admissions, prior antianxiety medications, prior antipsychotic medications, parental history of psychiatric admissions, and the woman’s Charlson Comorbidity Index and the time-invariant covariate of parental educational level when the woman was 15 years of age to the basic model.

To more closely examine antidepressant use around the time of abortion and childbirth, our second set of analyses examined incidence rates (IRs) of first-time antidepressant use in the year before and year after an abortion and in the year before and year after a childbirth in 2-month increments. This allowed us to see whether the antidepressant use varied bimonthly in the 12 months before to 12 months after the abortion and similarly in the 12 months before to 12 months after the childbirth. We also examined IRRs using the 11th and 12th month before the abortion or childbirth as the reference, adjusting for age and calendar year, allowing us to see whether the incidence of antidepressant use was higher at any time during the first 12 months after an abortion or childbirth.

Results

A total of 396 397 women were included in this study. Of these, 17 294 (4.4%) had a record of at least 1 first-trimester abortion and no children, 72 052 (18.2%) had at least 1 childbirth and no abortions, 13 540 (3.4%) had at least 1 abortion and 1 childbirth, and 293 511 (74.1%) had neither an abortion nor a childbirth. Of 396 397 women overall, 59 465 (15.0%) women redeemed at least 1 antidepressant prescription; among 30 834 women who had an abortion, 5705 (18.5%) initiated antidepressant use after a first abortion; among 85 592 women who gave birth, 10 825 (12.7%) initiated antidepressant use after a first childbirth.

The number of women who redeemed antidepressant prescriptions by study variables and the unadjusted IR of redeeming antidepressant prescriptions per 1000 woman-years at risk are presented in Table 1. Relative to the 365 563 women who had no abortion (IR, 22.5; 95% CI, 22.3-22.7), women’s rate of redeeming antidepressant prescriptions was higher in the year before (IR, 45.7; 95% CI, 43.3-48.3), the year after (IR, 49.6; 95% CI, 47.1-52.3), more than 1 to 5 years after (IR, 40.5; 95% CI, 39.1-42.0), and more than 5 years after (IR, 36.5; 95% CI, 34.6-38.5) an abortion. However, the rate of new antidepressant use was the same in the year before and year after and decreased with increasing time after the abortion. Relative to the 310 805 women who had no childbirth (IR, 22.6; 95% CI, 22.4-22.8), women’s unadjusted rate of redeeming antidepressant prescriptions was lower during the year before childbirth (IR, 11.1; 95% CI, 10.3-11.9), similar during the year after childbirth (IR, 22.1; 95% CI, 21.0-23.2), and increased with increasing time after 1 year after childbirth (>1 to 5 years after childbirth: IR, 36.0; 95% CI, 35.1-36.9; >5 years after childbirth: IR, 49.7; 95% CI, 47.8-51.6).

Table 1. Study Variables by First-Time Antidepressant Use.

| Variable | No. of Women With First Redeemed Antidepressant Prescription (n = 59 465) | Woman-Years at Risk of First Redeemed Antidepressant Prescription (n = 2 502 659) | Unadjusted Rate of New Redeemed Antidepressant Prescriptions per 1000 Woman-Years at Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abortion | |||

| No abortion | 52 475 | 2 336 237 | 22.5 (22.3-22.7) |

| Year before abortion | 1285 | 28 115 | 45.7 (43.3-48 .3) |

| Year after abortion | 1372 | 27 653 | 49.6 (47.1-52.3) |

| >1-5 y After abortion | 2986 | 73 767 | 40.5 (39.1-42.0) |

| >5 y After abortion | 1347 | 36 887 | 36.5 (34.6-38.5) |

| Childbirth | |||

| No childbirth | 48 176 | 2 132 471 | 22.6 (22.4-22.8) |

| Year before childbirth | 814 | 73 569 | 11.1 (10.3-11.9) |

| Year after childbirth | 1436 | 65 090 | 22.1 (21.0-23.2) |

| >1-5 y After childbirth | 6459 | 179 585 | 36.0 (35.1-36.9) |

| >5 y After childbirth | 2580 | 51 944 | 49.7 (47.8-51.6) |

| History of psychiatric contact | |||

| No | 45 616 | 2 374 605 | 19.2 (19.0-19.4) |

| Yes | 13 849 | 128 054 | 108.2 (106.4-110.0) |

| History of receiving antianxiety medication | |||

| No | 48 853 | 1 386 075 | 20.5 (20.3-20.7) |

| Yes | 10 612 | 116 584 | 91.0 (89.3-92.8) |

| History of receiving antipsychotic medication | |||

| No | 56 448 | 2 486 341 | 22.7 (22.5-22.9) |

| Yes | 3017 | 16 318 | 184.9 (178.4-191.6) |

| Maternal history of psychiatric contact | |||

| No | 50 940 | 2 291 742 | 22.2 (22.0-22.4) |

| Yes | 8525 | 210 916 | 40.4 (39.6-41.3) |

| Paternal history of psychiatric contact | |||

| No | 52 242 | 2 317 045 | 22.6 (22.4-22.7) |

| Yes | 7223 | 185 614 | 38.9 (38.0-39.8) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Indexa | |||

| 0 | 53 309 | 2 329 096 | 22.9 (22.7-23.1) |

| 1 | 4832 | 137 674 | 35.1 (34.1-36.1) |

| ≥2 | 1324 | 35 888 | 36.9 (35.0-38.9) |

Scoring for the Charlson Comorbidity Index is explained in the Variables and Covariates subsection of the Measures subsection of the Methods section.

Survival Analysis

Results from the survival analysis are presented in Table 2. In the basic and fully adjusted models, relative to women who had not had an abortion, women who had a first abortion had a higher risk of first-time antidepressant use. However, this risk of first-time use of antidepressant medication was similar in the year before an abortion (basic model: IRR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.73-1.93; fully adjusted model: IRR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.38-1.54) and after an abortion (basic model: IRR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.87-2.08; fully adjusted model: IRR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.45-1.62), and it decreased with increasing time after the abortion (for >1 to 5 years, basic model: IRR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.55-1.67; for >1 to 5 years, fully adjusted model: IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.19-1.29; for >5 years, basic model: IRR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.39-1.56; and for >5 years, fully adjusted model: IRR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.05-1.18). Furthermore, the association between abortion and first antidepressant use decreased from the basic model to the fully adjusted model, indicating that these other factors are confounding the association between having an abortion and antidepressant use.

Table 2. Adjusted Incident Rate Ratios (95% CI) of Antidepressant Use by Time Relative to First Abortion and First Childbirth.

| Variable | Basic Modela | Fully Adjusted Modelb |

|---|---|---|

| Abortion | ||

| No abortionc | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Year before abortion | 1.83 (1.73-1.93) | 1.46 (1.38-1.54) |

| Year after abortion | 1.97 (1.87-2.08) | 1.54 (1.45-1.62) |

| >1-5 y After abortion | 1.61 (1.55-1.67) | 1.24 (1.19-1.29) |

| >5 y After abortion | 1.47 (1.39-1.56) | 1.12 (1.05-1.18) |

| Childbirth | ||

| No childbirthc | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Year before childbirth | 0.52 (0.49-0.56) | 0.47 (0.43-0.50) |

| Year after childbirth | 1.06 (1.01-1.12) | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) |

| >1-5 y After childbirth | 1.82 (1.77-1.87) | 1.52 (1.47-1.56) |

| >5 y After childbirth | 2.81 (2.68-2.94) | 1.99 (1.91-2.09) |

| History of psychiatric contact | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 3.70 (3.62-3.78) | |

| History of receiving antianxiety medication | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 3.03 (2.96-3.10) | |

| History of receiving antipsychotic medication | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 1.88 (1.81-1.96) | |

| Maternal history of psychiatric contact | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 1.21 (1.18-1.24) | |

| Paternal history of psychiatric contact | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 1.25 (1.22-1.29) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Indexd | ||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | |

| 1 | 1.24 (1.21-1.28) | |

| ≥2 | 1.17 (1.11-1.24) |

Model includes abortion, childbirth, age, and cohort (calendar year).

Model includes abortion, childbirth, age, cohort (calendar year), history of psychiatric contact, history of receiving antianxiety medication, history of receiving antipsychotic medication, maternal and paternal history of psychiatric illness, and mother’s and father’s educational level when the woman was 15 years old.

Excluding the year before the first childbirth or abortion.

Scoring for the Charlson Comorbidity Index is explained in the Variables and Covariates subsection of the Measures subsection of the Methods section.

Relative to women with no childbirth, women who gave birth had a lower risk of first-time antidepressant use in the year before childbirth (basic model: IRR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.49-0.56; fully adjusted model: IRR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.43-0.50) and a slightly higher risk in the basic adjusted model (IRR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.12) but a lower risk in the fully adjusted model in the year after childbirth (IRR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.88-0.98). More than 1 year after childbirth, childbirth increased women’s likelihood of using antidepressants (for >1 to 5 years, basic model: IRR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.77-1.87; for >1 to 5 years, fully adjusted model: IRR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.47-1.56; for >5 years, basic model: IRR, 2.81; 95% CI, 2.68-2.94; and for >5 years, fully adjusted model: IRR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.91-2.09). Across all women in the sample (N = 396 397), the strongest risk factors associated with antidepressant use (Table 2) in the fully adjusted model were having a previous psychiatric contact (IRR, 3.70; 95% CI, 3.62-3.78), having previously obtained an antianxiety medication (IRR, 3.03; 95% CI, 2.99-3.10), and having previously obtained antipsychotic medication (IRR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.81-1.96).

Risk Factors and Rates of Antidepressant Use

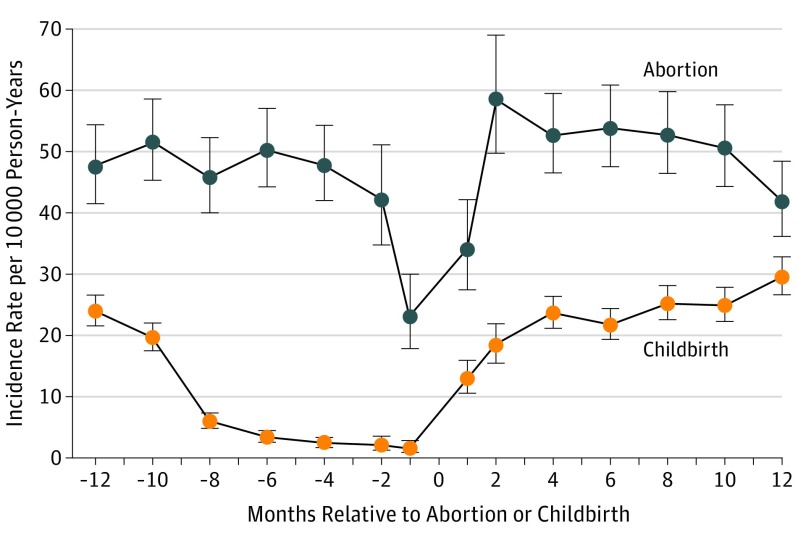

Rates of antidepressant use, assessed in 2-month increments, were relatively stable during the year before and year after an abortion, with a decrease immediately preceding and just after the procedure (Figure 1). Rates of new antidepressant use varied from the year before to the year after childbirth. The incidence of new antidepressant use was lower during pregnancy than it was just before pregnancy or after childbirth.

Figure 1. Incidence Rates of Obtaining a First Antidepressant Prescription Before and After Having an Abortion and Before and After Childbirth.

The negative numbers indicate the number of months before the abortion or childbirth. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

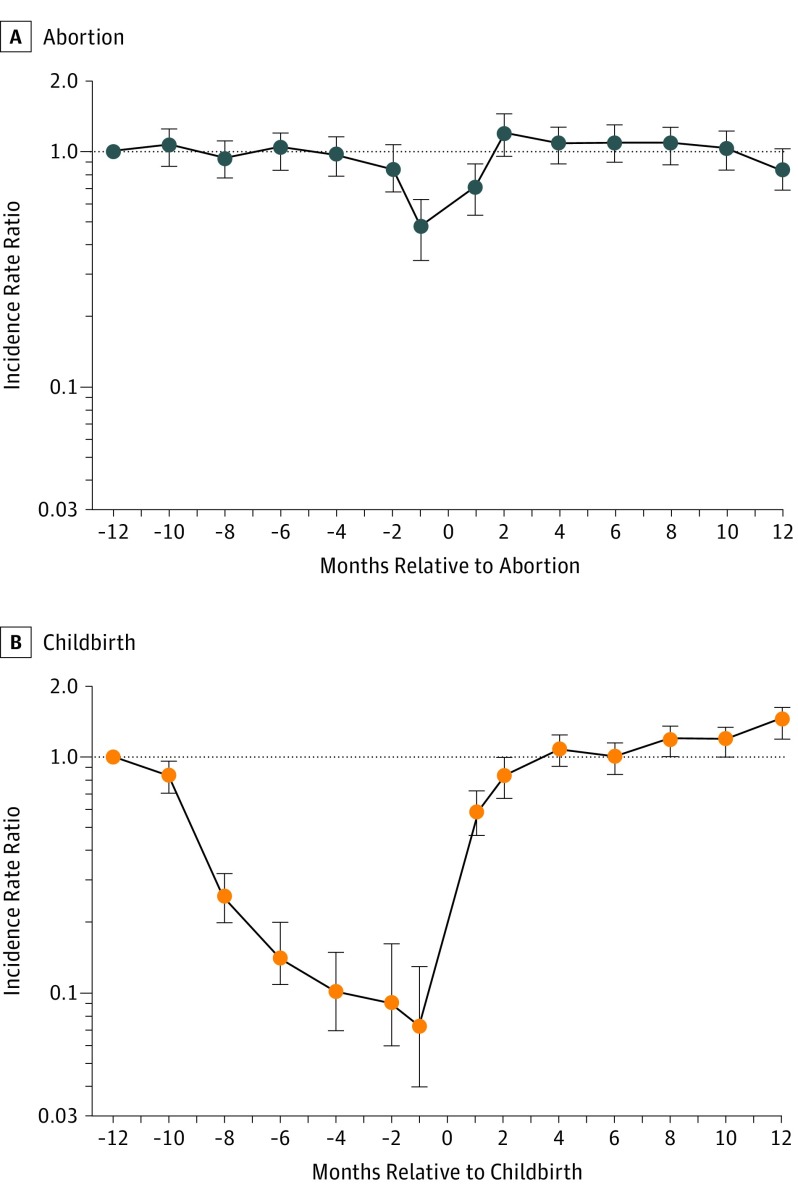

Figure 2 presents age-adjusted and calendar-year–adjusted IRRs of first-time antidepressant use in bimonthly increments from the year before and year after having an abortion and the year before and year after childbirth compared with the 11th and 12th month before the respective pregnancy outcome. Figure 2A shows that, compared with the 11th and 12th month before an abortion, there was less likelihood of first-time antidepressant use in the month before and month after an abortion and no other differences in likelihood of use when compared with other months in this 24-month period. Figure 2B shows that, compared with risk during the 11th and 12th month before childbirth, women’s risk of antidepressant use was lower during the remaining months before childbirth (ie, during pregnancy) and in the first month after childbirth but was higher in the 11th and 12th months after childbirth.

Figure 2. Incident Rate Ratios of Obtaining a First Antidepressant Prescription Before and After Having a First-Trimester Abortion or Childbirth.

A, Data for women who had a first-trimester first abortion. B, Data for women who had a first childbirth. Both models are adjusted for age and calendar year. The negative numbers indicate the number of months before the abortion or childbirth. The horizontal line indicates the reference group of 11 to 12 months before the abortion or childbirth. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

Using data on abortion, childbirth, and antidepressant prescriptions collected over time and not by self-report, we examined risk of antidepressant use associated with a first abortion during the first trimester and childbirth. Compared with women who did not have an abortion, those who had an abortion had a higher rate of antidepressant use. A close look at the data, however, suggests that the higher rates of antidepressant use had less to do with having an abortion than with other risk factors for depression among women who had an abortion. That is, the increased risk of depression did not change from the year before to the year after an abortion. And contrary to previous claims that abortion has long-term adverse effects,24 the risk of depression decreased as more time elapsed after the abortion. Furthermore, the risk of first-time antidepressant use for all times relative to an abortion decreased in the fully adjusted model relative to the basic model. This finding indicates that preexisting mental health conditions and the other covariates are confounding the association between abortion and antidepressant use, which supports other research findings.5,11,25 Had we been able to consider other factors related to abortion and antidepressant use, such as intimate partner violence or a recent breakup,5,11,26 the association may have been reduced further and not have been statistically significant, as other research has found.5,6,11 Moreover, the strongest risk factors for first-time antidepressant use were indicators of earlier mental health problems. Taking all of these results together, it is possible that mental health problems may lead women to have unintended pregnancies and abortions, as other research has found.5,27

Compared with not having a childbirth, having a childbirth was associated with a decreased risk of antidepressant use in the year before childbirth and in the year after childbirth. Nevertheless, absolute rates of antidepressant use increased in the year after childbirth compared with the year before childbirth, and the risk of first-time antidepressant use in the year after childbirth was greater than the risk in the year before childbirth relative to not giving birth. These results support other findings that have shown that the rate of antidepressant use during a pregnancy that ends in childbirth is lower during pregnancy than in the postpartum period.28,29 It is not clear whether this is due to a lower risk of mental disorders during pregnancy or to a greater reluctance to take medication during pregnancy than in the postpartum period. In contrast to our finding that the risk of antidepressant use decreased as the time after the abortion increased, the risk of antidepressant use increased with increasing time after childbirth.

While the analyses do not directly compare the risk of antidepressant use among women who have an abortion with that among women who give birth, the analyses do compare patterns of antidepressant use around a first abortion vs around a first childbirth. We find that, in the year before and in the year after a first abortion, IRs of new antidepressant use are higher than in the year before and in the year after a first childbirth. However, as mentioned, the rate did not change from the year before to the year after an abortion, although it did increase from the year before to the year after a childbirth. We used the group of women who gave birth because that is the alternative to having an abortion, recognizing that the pattern of antidepressant use around childbirth may have been different if we had information on pregnancy intention. Indeed, other research has considered intention by comparing women who were seeking an abortion and obtained one vs those who were denied one and found that women who were denied an abortion initially had higher levels of anxiety symptoms than women who received an abortion; this difference in levels of anxiety symptoms did not persist over a 5-year follow-up period.6 Similar levels of depressive symptoms were found shortly after an abortion was sought and throughout a 5-year follow-up period.6 These findings illustrate that, when pregnancy intention is considered and the abortion and delivery groups are similar in terms of other life circumstances, having an abortion is not associated with a higher likelihood of mental health problems.

Limitations

A limitation of the existing research is that, owing to confidentiality policies, we have only the month and year of childbirth. Thus, we were only able to examine IRs (Figure 1) and IRRs (Figure 2) in 2-month increments in the year before and the year after an abortion or childbirth. Nevertheless, we expect findings would be similar had we been able to use 1-month increments. Another limitation is that we do not know the reasons for the antidepressant prescriptions. While antidepressants are most likely to have been prescribed for depression or anxiety,10,12 they may have been prescribed for other reasons, such as insomnia or pain.10

Finally, it is not clear whether the results can be generalized to other contexts. Indeed, results may differ where access to abortion is legally restricted or where antidepressants are not widely accessible. Little research on abortion and mental health has been conducted in places were abortion is highly restricted. Nevertheless, our conclusions are similar to those of other research conducted in the United States using nationally representative data.5,11

Conclusions

Women who have abortions are more likely to use antidepressants compared with women who do not have abortions. However, 3 findings support the conclusion that increased use of antidepressants is not attributable to having had an abortion but to differences in risk factors for depression. First, if having an abortion is causally related to depression, one would expect a higher rate of first antidepressant use after the procedure than before the procedure, yet rates of antidepressant use were no higher in the year after having an abortion than in the year before having an abortion. Second, if there are lagged effects of abortion, one would expect an increase in the rate of depression over time, but rates of antidepressant use decreased as more time elapsed. Finally, the differences in rates of antidepressant use between women who had an abortion and women who did not have an abortion were substantially reduced when adjusted for earlier mental health conditions, parental mental health conditions, parental educational level, and physical health. This suggests that, compared with women who do not have an abortion, women who have an abortion may be at higher risk of depression after undergoing the procedure because they were at higher risk to begin with. Consequently, policies based on the notion that having an abortion harms women’s mental health may be misinformed.

References

- 1.Major B, Appelbaum M, Beckman L, Dutton MA, Russo NF, West C. Abortion and mental health: evaluating the evidence. Am Psychol. 2009;64(9):863-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Induced abortion and Mental Health: a Systematic Review of the Mental Health Outcomes of induced Abortion, Including Their Prevalence and Associated Factors. London, UK: Academy of Medical Royal Colleges; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Lidegaard Ø, Mortensen PB. Induced first-trimester abortion and risk of mental disorder. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(4):332-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Lidegaard Ø, Mortensen PB. First-time first-trimester induced abortion and risk of readmission to a psychiatric hospital in women with a history of treated mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinberg JR, McCulloch CE, Adler NE. Abortion and mental health: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2, pt 1):263-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biggs MA, Upadhyay UD, McCulloch CE, Foster DG. Women’s mental health and well-being 5 years after receiving or being denied an abortion: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(2):169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman PK. Abortion and mental health: quantitative synthesis and analysis of research published 1995-2009. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(3):180-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones RK, Kost K. Underreporting of induced and spontaneous abortion in the United States. Stud Fam Plann. 2007;38(3):187-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannell CF, Marquis KH, Laurent A. A summary of studies of interviewing methodology. Vital Health Stat 2. 1977;69(69):i-viii, 1-78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong J, Motulsky A, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Abrahamowicz M, Tamblyn R. Treatment indications for antidepressants prescribed in primary care in Quebec, Canada, 2006-2015. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2230-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberg JR, Finer LB. Examining the association of abortion history and current mental health. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(1):72-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noordam R, Aarts N, Verhamme KM, Sturkenboom MCM, Stricker BH, Visser LE. Prescription and indication trends of antidepressant drugs in the Netherlands between 1996 and 2012. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(3):369-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):38-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legalt Provokerede Aborter 2005 (oreløbig opgørelse). Copenhagen, Denmark: Sundhedsstyrelsen; 2006:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jerman J, Jones RK, Onda T. Characteristics of U.S. Abortion Patients in 2014 and Changes Since 2008. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2016. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/characteristics-us-abortion-patients-2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timmermans B. The Danish Integrated Database for Labor Market Research: towards demystification for the English speaking audience. DRUID Working Paper No. 10-16. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46451548_The_Danish_Integrated_Database_for_Labor_Market_Research_Towards_Demystification_for_the_English_Speaking_Audience.

- 20.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash TL, Sørensen HT. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson Comorbidity Index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:83-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM. Abortion and mental health disorders: evidence from a 30-year longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(6):444-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Speckhard AC, Rue VM. Postabortion syndrome: an emerging public health concern. J Soc Issues. 1992;48(3):95-119. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1992.tb00899.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Ditzhuijzen J, Ten Have M, de Graaf R, Lugtig P, van Nijnatten CHCJ, Vollebergh WAM. Incidence and recurrence of common mental disorders after abortion. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:200-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones RK, Frohwirth L, Moore AM. More than poverty: disruptive events among women having abortions in the USA. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2013;39(1):36-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall KS, Kusunoki Y, Gatny H, Barber J. The risk of unintended pregnancy among young women with mental health symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2014;100:62-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munk-Olsen T, Gasse C, Laursen TM. Prevalence of antidepressant use and contacts with psychiatrists and psychologists in pregnant and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(4):318-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munk-Olsen T, Maegbaek ML, Johannsen BM, et al. Perinatal psychiatric episodes: a population-based study on treatment incidence and prevalence. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(10):e919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]