Key Points

Question

Did the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Medicaid primary care payment increase change physician participation in Medicaid or Medicaid service volume?

Findings

In a longitudinal analysis of 2012 to 2015 data from 20 723 primary care physicians, the payment increase had no association with participation in Medicaid or Medicaid service volume in aggregate or for physician subpopulations. This null result was robust to sensitivity analyses, including different model specifications and date ranges.

Meaning

The payment increase did not have the intended outcomes. The limited duration and design of the policy may have dampened its potency.

Abstract

Importance

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) increased 2013 to 2014 Medicaid payment rates for qualifying primary care physicians (PCPs) and services to higher Medicare payment levels, with the goal of improving primary care access for Medicaid enrollees.

Objectives

To evaluate the payment increase policy and to assess whether it was associated with changes in Medicaid participation rates or Medicaid service volume among PCPs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study used 2012 to 2015 IMS Health aggregated medical claims and encounter data from PCPs eligible for the payment increase practicing in all states except Alaska and Hawaii and included 20 723 PCPs with observations in each month from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2015. Data are for professional services performed in ambulatory settings, including office, hospital outpatient department, and emergency department. Regression models were used to test whether outcomes differed in months subject to higher payment rates relative to months before the increase and after the expiration of the increase in some states. The models controlled for time-invariant physician characteristics and time-varying characteristics, such as Medicaid enrollment. Interaction terms were included to estimate differential associations in subgroups of states (eg, by Medicaid managed care penetration) and physicians (eg, by specialty).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Physician-month records subject to higher Medicaid payment rates were flagged using state-specific implementation and end dates for the payment increase. Five outcomes were measured for each physician-month observation, including (1) an indicator for seeing any patients enrolled in Medicaid, (2) an indicator for seeing more than 5 patients enrolled in Medicaid, (3) the Medicaid share of total patients, (4) a count of new patient evaluation and management visits furnished to patients enrolled in Medicaid, and (5) a count of existing patient evaluation and management visits furnished to patients enrolled in Medicaid.

Results

Among 20 723 PCPs, the payment increase had no association with PCP participation in Medicaid or Medicaid service volume. The estimated average marginal effects for all 5 outcomes were not statistically distinguishable from 0. This null result was robust to sensitivity analyses, including different time trend specifications and analyses focusing on the payment increase implementation and expiration time frames. Descriptively, the Medicaid share of patients increased by about 25% from 2012 to 2015, although the share did not increase differentially in states and months subject to higher payment rates.

Conclusions and Relevance

The limited duration and design of the payment increase may have dampened its effectiveness. Future efforts to improve access through payment changes or other means can benefit from better understanding of the outcomes of this policy.

This longitudinal analysis evaluates the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Medicaid primary care payment increase policy and assesses whether it was associated with changes in Medicaid participation rates or Medicaid service volume among primary care physicians.

Introduction

One of the provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) increased 2013 to 2014 Medicaid payment rates for specific services delivered by primary care practitioners to higher Medicare payment levels. This payment increase was intended to improve access to primary care for new and existing Medicaid enrollees through the then nationwide expansion of Medicaid eligibility in 2014. All else being equal, higher payment rates were expected to incentivize some nonparticipating primary care practitioners to start seeing patients enrolled in Medicaid and encourage already participating physicians to accept patients newly enrolled, as well as provide more services to Medicaid enrollees. The payment increase was financed using only federal funds and was implemented by state Medicaid programs. Although Congress did not act to extend the increase beyond 2014, some states continued to pay higher rates, and current proposals to permit individuals to buy into Medicaid coverage include resumption of the ACA payment increase.

Before the increase, Medicaid payments for primary care and other services were lower than Medicare and private payment rates in most states, despite a statutory requirement that rates be sufficient to enlist enough health care providers such that access to care for Medicaid enrollees mirrors access for the general population in the same area.1 Low Medicaid rates together with other factors (eg, payment delays and paperwork) deter some physicians from providing care to patients enrolled in Medicaid,2 particularly for practices that can reach capacity with patients with other coverage. In 2011, one-third of physicians nationwide did not accept new Medicaid enrollees, with the primary reason cited as low payment rates.3,4 Rhodes et al5 found that Medicaid enrollees’ ability to schedule a new appointment with a primary care practice was 27 percentage points less than for patients with private insurance.

The payment increase was in effect in 2013 to 2014 and applied to primary care practitioners and services under fee-for-service and managed care Medicaid. To receive higher rates, practitioners had to self-attest to their eligibility, specifically that they were board certified in a primary care specialty or provided above a threshold volume of primary care services. States collected attestation forms and identified eligible primary care practitioners to managed care organizations where appropriate.6,7,8 Qualifying practitioners received the enhanced rates for evaluation and management (E&M) services (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes 99201-99499) and vaccine administration (CPT codes 90460-90461, 90471-90473, and successor codes).

The magnitude of the payment increase relative to preincrease rates was considerable in most states. Using fee-for-service fee schedules, which may underestimate Medicaid managed care rates, Zuckerman and Goin9 estimated that payments would increase by 73% in aggregate, ranging from no change in Alaska and North Dakota to a near doubling of payment rates in Rhode Island, New York, California, and Michigan.

The payment increase and its full federal funding ended at the end of 2014. Fifteen states and the District of Columbia then opted to continue paying for Medicaid primary care services at higher rates (although sometimes at levels in between the rates before and during the 2013 to 2014 payment increase); 1 other state—Alaska—paid Medicaid rates that were higher than Medicare rates prior to the payment increase and continued to do so through calendar year 2015.6

Increasing Medicaid provider payments is one approach to increasing access. Other ways to pursue this goal include investments in health centers, an increase in the workforce supply in underserved communities via the National Health Service Corps, or telemedicine. A key question that should inform the discussion of the use of payment rates to improve access is whether the ACA payment increase had the intended outcomes of increased Medicaid participation among physicians and higher levels of primary care services for new and existing Medicaid enrollees.

There is limited evidence to date on the effectiveness of the policy. Polsky et al10 and Candon et al11 applied an audit design to record availability and waiting times for appointments before, during, and after the payment increase in 10 states. They found that, while waiting times revealed no significant change across the 2 audit periods, there was an increase in appointment availability for Medicaid patients that scaled with the magnitude of the payment increase. This approach had several limitations. First, the researchers studied appointment availability in states with mandated Medicaid managed care and practices participating in managed care and thus could not draw conclusions on the associations of the policy in other states or for fee-for-service Medicaid. Second, their investigations explored appointment availability among existing Medicaid health care providers and did not account for changes in participating clinics since the policy’s initiation. Third, there are important differences between appointment availability and realized visits.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC)6 and RAND Corporation8 reports describing the experiences of Medicaid administrators, collected through semistructured interviews, suggest smaller changes from the payment increase. These reports highlight implementation issues, including delays in implementing the provision, practitioner self-attestation, and managed care complexity, that may have dulled the effectiveness of the payment increase. Overall, state Medicaid programs reported that they did not have enough data to evaluate the associations of the payment increase, although anecdotally they reported 0% to 1% increases in Medicaid participation and 0% to 7% increases in primary care service volume.6

Methods

This study used claims data from primary care physicians (PCPs) to evaluate the associations of the payment increase with Medicaid participation and service volume. We tracked a stable panel of physicians from all states except Alaska and Hawaii before, during, and after the payment increase was in effect. We used time-series regression to test whether physician claims activity differed in months subject to higher payment rates relative to months before the increase and after the expiration of the increase in some states.

Claims data report the actual use of specific health care services targeted by the payment increase and thus offer a clearer signal on whether the policy had its intended outcome compared with physician self-report of Medicaid participation, administrative enrollment data, or audit studies, all of which may overestimate actual participation and use. While claims data provide more nuanced information on the extent to which physicians treat Medicaid enrollees than can be typically collected from these other sources, additional steps are needed to translate the data into practical measures of Medicaid participation, as described herein.

Data Source

We used 2012 to 2015 medical claims and encounter data from IMS Health (IMS), now IQVIA (Danbury, Connecticut, and Research Triangle Park, North Carolina), from a sample of PCPs. IMS aggregates and standardizes submitted electronic claims and encounter data from a convenience sample of clearinghouses and processors. Our data are for professional services performed in the ambulatory setting, including office, hospital outpatient department, and emergency department places of service. The data include counts of services per month with Medicaid fee for service, Medicaid managed care, Medicare, commercial, and other payer categories. Separately, the data include counts of patients per month with services paid by the same payer categories. Payer categories were assigned by IMS based on plan name and other information. Levels and trends in the IMS data are generally similar to those in other sources of physician data, including the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, the American Medical Association Physician Practice Benchmark Survey, and ACAView (eAppendix in the Supplement). The study was approved by RAND Corporation’s Human Subjects Protection Committee. Informed consent was not required or applicable.

Sample

Our initial sample included all 23 992 PCPs contributing to the IMS Health data with a specialty or subspecialty. Of these physicians, 86.4% (20 723) had observations for each of the 48 months from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2015. We used this stable panel of physicians for our analyses. These physicians are distributed across specialty and geography but not necessarily in proportion to the totality of PCPs in the United States.

Poststratification Weighting

Table 1 lists statistics for physicians of the same primary care specialties from SK&A (Irvine, California), a health care marketing firm that maintains a national database of physicians that is used primarily for marketing purposes. The SK&A data generally match other data (eg, the American Medical Association’s Master File and the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System) on the totality of US physicians in terms of specialty and location, particularly for office-based physicians, but the SK&A data are updated more frequently.13,14 The SK&A data suggest that the IMS sample contains about 11% of all US PCPs who qualified for the payment increase through the specialty criterion. We developed poststratification weights to inflate the IMS sample to resemble the universe of PCPs in the SK&A data proportionally in terms of specialty (internal medicine, general practice and family medicine, and pediatrics) and practice state. The specific weight applied to each physician is the count of the SK&A relative to IMS physicians in each combination of specialty and state. The resulting weighted sample matches the 2012 SK&A total number of PCPs and the 2012 SK&A joint distribution of PCPs across specialties and states (Table 1).

Table 1. Primary Care Physician Characteristicsa.

| Variable | % | |

|---|---|---|

| IMS Sample Unweighted (n = 20 723) | SK&A and IMS Sample Weighted (n = 186 164) | |

| Specialty | ||

| Internal medicine | 51.7 | 35.1 |

| General practice and family medicine | 29.6 | 44.0 |

| Pediatrics | 18.7 | 20.9 |

| State Characteristics | ||

| Specific states | ||

| Florida | 9.3 | 6.1 |

| New York | 7.2 | 7.1 |

| Ohio | 6.6 | 3.9 |

| New Jersey | 5.9 | 3.3 |

| California | 5.2 | 11.5 |

| Texas | 5.3 | 6.4 |

| Michigan | 5.1 | 3.8 |

| Georgia | 4.8 | 2.6 |

| Pennsylvania | 4.6 | 4.8 |

| All other states | 46.2 | 50.3 |

| By Medicaid expansion | ||

| Expanded on or before Jan 1, 2014 | 54.8 | 56.1 |

| Did not expand by Jan 1, 2014 | 45.2 | 43.9 |

| Mean Medicaid to Medicare fee ratio in 2012b | 60.9 | 60.8 |

| Mean Medicaid managed care penetration in 2013c | 71.4 | 71.1 |

| By payment bump implementation | ||

| Through fee schedule | 71.4 | 72.5 |

| Not through fee schedule | 28.6 | 27.5 |

| By payment increase continuation | ||

| Continued payment increase | 14.4 | 13.9 |

| Did not continue payment increase | 85.6 | 86.1 |

Source: RAND Corporation (Arlington, Virginia) analysis of IMS Health (now IQVIA, Danbury, Connecticut, and Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) aggregated 2012 to 2015 physician claims data and 2012 SK&A (Irvine, California) data. Some percentages do not sum to 100% because of rounding.

Medicaid to Medicare primary care fee schedule ratios are from the study by Zuckerman and Goin (for The Urban Institute).9

Medicaid managed care penetration is from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services12 (CMS, winter 2015) as summarized on the Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts website (Total Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment, 2014; https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mc-enrollment/), accessed September 30, 2017.

Supplemental State-Level Data

We supplemented the claims data with information from other sources, including state-level Medicaid-to-Medicare fee ratios for primary care services9; state-level Medicaid managed care penetration from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)12; state Medicaid eligibility expansion status as of January 1, 2014, from the Kaiser Family Foundation15; and time-varying data from CMS Medicaid enrollment reports.16 We also used information on payment increase implementation from State Plan Amendment documents submitted to the CMS. The State Plan Amendment documents indicate whether each state’s Medicaid payments include site of service and/or geographic adjustments and whether states implemented the payment increase through a fee schedule adjustment or supplemental payment. We separately received information from the CMS on when the first payments under the State Plan Amendments were made.

Outcomes and Main Regression Models

We measured 5 outcomes for each physician-month observation. These included (1) an indicator for seeing any patients enrolled in Medicaid, (2) an indicator for seeing more than 5 patients enrolled in Medicaid, (3) the Medicaid share of total patients, (4) a count of new patient evaluation and management visits furnished to patients enrolled in Medicaid, and (5) a count of existing patient evaluation and management visits furnished to patients enrolled in Medicaid.

We used physician fixed-effects regression models to estimate the association between the payment increase policy and each outcome (Poisson count models and linear probability models estimated by mean differencing the data at the physician level, as appropriate).17,18,19,20 Each model included a policy variable that varies within each state over time and equals 1 for months in each state subject to higher rates. Each model also controlled for time-invariant physician-level unobservables that may be associated with outcomes, as well as for time-varying Medicaid enrollment and states’ decisions to expand Medicaid eligibility. Our preferred models included study-month indicators to control for shared shocks that could change outcomes irrespective of the payment increase.

Because of variation across state Medicaid programs and the latitude that states and associated managed care organizations had to implement the payment increase, we also included interactions between the policy indicator and 2012 values of other variables of interest, including state-level managed care penetration in quartiles (a proxy for the magnitude of the payment increase based on fee-for-service payment levels in quartiles) and physician specialty. These interaction terms accounted for differential associations of the policy in, eg, states with higher managed care penetration or states that had lower rates (proxied by fee-for-service rates) before the payment increase.

For our main results, we estimated count models for dependent variables with nonzero counts. We used robust SEs clustered at the state level for ordinary least squares models, as well as at the physician level for count models to account for correlations in residuals. Results are reported as estimated average marginal effects.

Sensitivity Analyses

We explored different approaches to modeling the time trend, including (1) linear and quadratic trends rather than study-month indicators and (2) calendar month indicators to address potential seasonality in Medicaid participation and service volume. These sensitivity analyses address the concern that controlling for study-month indicators may absorb some of the associations of the policy in months when the policy was in effect in all states.

We estimated models with state rather than physician fixed effects and models without weights. We also estimated models using subsets of our data, first using data from 2012 to 2013 to avoid possible confounding from the 2014 Medicaid eligibility expansion in some states and next using 2014 to 2015 data to examine the association between the expiration of the payment increases and outcomes. We estimated models using 2014 to 2015 data with and without a set of states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Michigan, Nebraska, Nevada, and South Carolina) that continued paying higher rates in 2015 but where the 2015 rates may have declined relative to the 2014 rates. Finally, we assessed whether inclusion of observations without Medicaid services (rather than only using observations with Medicaid volume) changed count model results.

Results

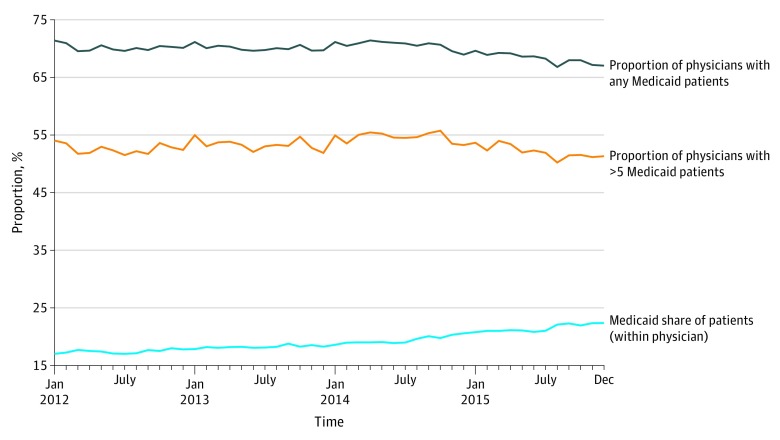

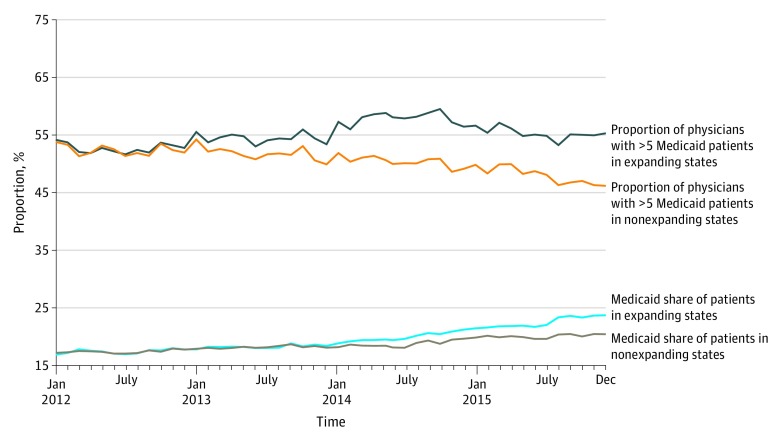

In unadjusted analyses, we found no changes over time (including through the payment increase implementation period) in the proportion of PCPs seeing any patients enrolled in Medicaid or more than 5 patients enrolled in Medicaid and found modest increases in the Medicaid share of patients (Figure 1). The proportion of PCPs seeing more than 5 Medicaid patients per month increased by 0.7% from the first 6 months of 2012 to the last 6 months of 2013 and then declined slightly through the end of 2015, for a net decrease of 0.2% over the full period. The average Medicaid share of patients increased from 15.5% in the first quarter of 2012 to 20.0% in the last quarter of 2015, although the increase was sharpest after the 2014 Medicaid eligibility expansion. Both of these outcomes increased differentially for states that expanded Medicaid eligibility compared with those that did not (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Unadjusted Primary Care Physician Medicaid Participation Measure Trends.

Analysis of IMS Health (now IQVIA, Danbury, Connecticut, and Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) aggregated 2012 to 2015 physician claims data.

Figure 2. Unadjusted Primary Care Physician Medicaid Participation Measure Trends by State Medicaid Expansion Status on January 1, 2014.

Analysis of IMS Health (now IQVIA, Danbury, Connecticut, and Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) aggregated 2012 to 2015 physician claims data.

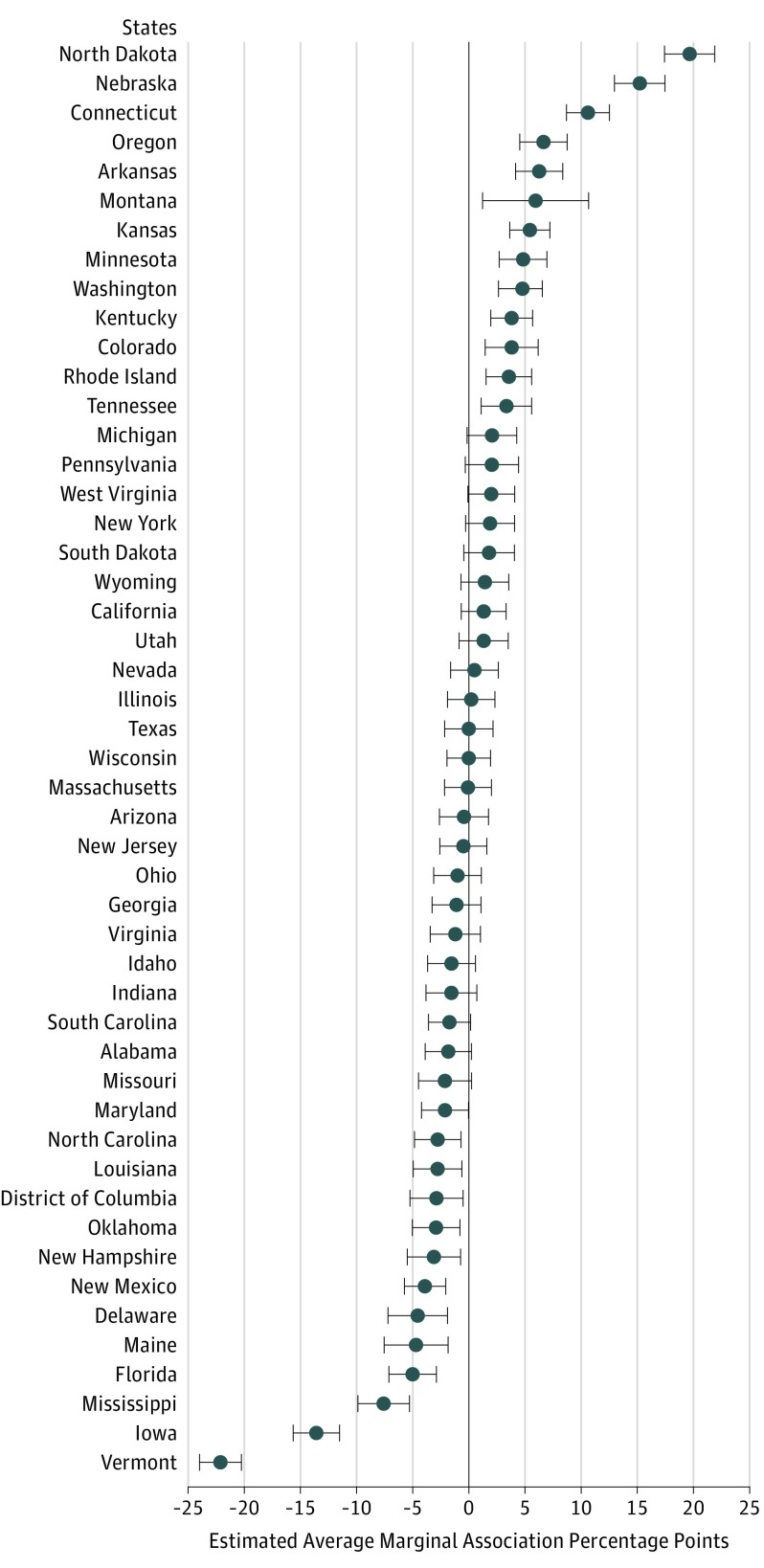

Table 2 lists estimated average marginal effects from regression models. None of the estimated outcomes are statistically significant at the .05 level. In addition, we did not find any average marginal effects that were statistically significantly different from zero in subpopulations of physicians defined by physician or state characteristics. Almost all average marginal effects for differences in state characteristics, including details of implementation of the payment increase and whether the state expanded Medicaid, were also not statistically significant (eTable 1 in the Supplement). In terms of control variables in our models, the coefficient on the Medicaid expansion indicator and enrollment was often positive and significant, suggesting a correlation between Medicaid eligibility expansion and study outcomes. Figure 3 shows the estimated average marginal effects for the share of PCPs with more than 5 patients enrolled in Medicaid per month by state. Estimated outcomes were variable across states, with negative and significant outcomes in 13 states and positive and significant outcomes in 13 states. State results for other outcomes follow a similar pattern (eFigures 1, 2, 3, and 4 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Estimated Change in Study Outcomes From Regression Modelsa.

| Variable | Estimated Average Marginal Effect (SE) |

|---|---|

| Any Medicaid patients, percentage points | 0.202 (1.197) |

| >5 Medicaid patients, percentage points | 0.438 (1.385) |

| Medicaid share of patients, percentage points | 0.034 (0.492) |

| New patient E&M services, No. | −3.071 (1.864) |

| Existing patient E&M services, No. | −0.055 (0.175) |

Abbreviation: E&M, evaluation and management.

Source: RAND Corporation (Arlington, Virginia) analysis of IMS (now IQVIA, Danbury, Connecticut, and Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) aggregated 2012 to 2015 physician claims data.

Figure 3. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by Primary Care Physician Practice State for the More Than 5 Medicaid Patients Outcome.

Analysis of IMS Health (now IQVIA, Danbury, Connecticut, and Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) aggregated 2012 to 2015 physician claims data. Whiskers indicate 95% CIs.

In sensitivity analyses, estimated average marginal effects were not significant in model specifications that included state rather than physician fixed effects or in models that included linear and quadratic trends rather than month fixed effects (eTable 2 in the Supplement). In models controlling for seasonality but without month fixed effects, we found that the proportion of PCPs with more than 5 patients enrolled in Medicaid is about 1 percentage point higher (on a base of about 52% in the preincrease period) in months and states subject to higher rates. We also found some statistically significant differences for this outcome across physician subpopulations, although the magnitudes of these associations were small (1-2 percentage points). We found no statistically significant outcomes of the payment increase from models estimated with 2012 to 2013 or 2014 to 2015 data only. Our main results were substantively unchanged when we omitted poststratification weights and when we used data from all physician month observations (including zeros) for count models.

Discussion

We found that the payment increase had limited association with Medicaid participation or Medicaid service volume based on the metrics defined for this study. This finding is contrary to hypotheses informed by evidence from analyses of cross-sectional data from before the payment increase showing strong positive associations between Medicaid payment and participation rates.4 Factors specific to this policy may have contributed to its limited association, including implementation challenges for states and managed care organizations that delayed payments to physicians, a 2-year policy duration, and the need for physicians to submit documentation to qualify for higher payment. Our empirical findings align with recent qualitative reports6,8 that (in addition to highlighting implementation challenges) found, through interviews with state Medicaid officials, that few of the physicians who enrolled to receive higher payments were new to Medicaid.

Limitations

There are some limitations to our analysis. First, our sample is not a random sample and may not be generalizable to the totality of PCPs in the United States. We address this concern in part by weighting our data to mirror the joint distribution of PCPs by specialty and state of practice. Second, nurse practitioners and physician assistants are not included in our sample. Services furnished by these practitioners but billed under a physician could appear in our data and inflate the apparent response to the payment increase. Third, our data include physician services delivered in the hospital outpatient and emergency department settings, but because of data limitations we are unable to assess whether the payment increase had a differential outcome in these settings. Fourth, we did not have access to payment rates under Medicaid managed care arrangements before the policy, and as a result we did not use an approach that would have linked the magnitude of the payment change to outcomes. However, we group states into quartiles by the generosity of their fee-for-service fee schedules for the purpose of exploring heterogeneous responses. Fifth, among states continuing to pay at higher rates in 2015, we did not differentiate between those paying Medicare rates and those paying rates between prior Medicaid rates and Medicare rates because of difficulties in identifying specific rates from fee schedules. Sixth, while the IMS data include services furnished under managed care arrangements and the total Medicaid volume in IMS roughly aligns with Medicaid volume in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, the IMS data may not capture all Medicaid managed care services. Seventh, while we controlled for states that expanded Medicaid eligibility in 2014, it remains empirically challenging to disentangle the outcomes of these 2 contemporaneous policies.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the ACA payment increase had little or no association with Medicaid participation and service volume. This does not mean that a differently formulated payment policy could not have achieved more robust outcomes or that states spending some of their own funds to maintain higher payment rates are erring. The short duration of the ACA payment increase, its delayed implementation, and its complicated attestation process may have contributed to our results. Policy makers should consider these empirical findings (as well as qualitative research on the outcomes of the payment increase) when designing potential future payment increases and comparing them with other possible strategies to improve access.

eAppendix. Benchmarking the IMS Sample to Other Data Sources

eTable 1. Estimated Average Marginal Effects for Subgroups of Physicians and States

eFigure 1. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by PCP Practice State, Any Medicaid Patient Outcome

eFigure 2. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by PCP Practice State, Medicaid Share of Patients Outcome

eFigure 3. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by PCP Practice State, New Patient E&M Claim Line Count Outcome

eFigure 4. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by PCP Practice State, Existing Patient E&M Claim Line Count Outcome

eTable 2. Estimated Change in Study Outcomes from Regression Models, Alternate Model Specifications

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS Medicaid program: payments for services furnished by certain primary care physicians and charges for vaccine administration under the Vaccines for Children program: final rule. Fed Regist. 2012;77(215):66669-66701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sloan F, Mitchell J, Cromwell J. Physician participation in state Medicaid programs. J Hum Resour. 1978;13(suppl):211-245. doi: 10.2307/145253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommers AS, Paradise J, Miller C. Physician willingness and resources to serve more Medicaid patients: perspectives from primary care physicians. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2011;1(2). doi: 10.5600/mmrr.001.02.a01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1673-1679. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes KV, Kenney GM, Friedman AB, et al. Primary care access for new patients on the eve of health care reform. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):861-869. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) An update on the Medicaid primary care payment increase. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/an-update-on-the-medicaid-primary-care-payment-increase-3/. Published March 2015. Accessed September 30, 2017.

- 7.Galewitz P. Few doctors get higher Medicaid fees. Washington Post May 19, 2013:A04.

- 8.Timbie JW, Buttorff C, Kotzias V, Case SR, Mahmud A. Examining the Implementation of the Medicaid Primary Care Payment Increase. Arlington, VA: RAND Corp; 2017. doi: 10.7249/RR1802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuckerman S, Goin D The Urban Institute. How much will Medicaid physician fees for primary care rise in 2013? evidence from a 2012 survey of Medicaid physician fees. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8398.pdf. Published December 2012. Accessed September 30, 2017.

- 10.Polsky D, Richards M, Basseyn S, et al. Appointment availability after increases in Medicaid payments for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):537-545. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1413299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candon M, Zuckerman S, Wissoker D, et al. Declining Medicaid fees and primary care appointment availability for new Medicaid patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):145-146. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment and Program Characteristics, 2013. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/data-and-systems/medicaid-managed-care/downloads/2013-managed-care-enrollment-report.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed September 30, 2017.

- 13.DesRoches CM, Barrett KA, Harvey BE, et al. The results are only as good as the sample: assessing three national physician sampling frames. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(suppl 3):S595-S601. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3380-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gresenz CR, Auerbach DI, Duarte F. Opportunities and challenges in supply-side simulation: physician-based models. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(2, pt 2):696-712. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser Family Foundation Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/. Published 2015. Accessed September 30, 2017.

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicaid and CHIP enrollment data. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/index.html. Published 2016. Accessed May 15, 2018.

- 17.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications. 8th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Regression Analysis of Count Data. 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013. Econometric Society Monograph 53. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139013567 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene W. The behaviour of the maximum likelihood estimator of limited dependent variable models in the presence of fixed effects. Econom J. 2004;7(1):98-119. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-423X.2004.00123.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matyas L, Sevestre P, eds. The Econometrics of Panel Data: Fundamentals and Recent Developments in Theory and Practice. Berlin-Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2008. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75892-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Benchmarking the IMS Sample to Other Data Sources

eTable 1. Estimated Average Marginal Effects for Subgroups of Physicians and States

eFigure 1. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by PCP Practice State, Any Medicaid Patient Outcome

eFigure 2. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by PCP Practice State, Medicaid Share of Patients Outcome

eFigure 3. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by PCP Practice State, New Patient E&M Claim Line Count Outcome

eFigure 4. Estimated Average Marginal Effects by PCP Practice State, Existing Patient E&M Claim Line Count Outcome

eTable 2. Estimated Change in Study Outcomes from Regression Models, Alternate Model Specifications