Abstract

This study examines how uncompensated care, provision of low-profit services, and financial stability differed between nonprofit and public hospitals in the United States that were participating in the 340B drug pricing plan compared with nonparticipating hospitals in 2015.

The 340B program was initiated in 1992 by the US Congress to allow participating hospitals to generate additional revenue by purchasing certain drugs used for outpatient care at an approximately 22% discount while charging payers the full price.1,2 The program was designed to support hospitals caring for uninsured patients and low-income patients with Medicare and Medicaid coverage, allowing the hospitals to reach “more eligible patients” and provide “more comprehensive services.”2(p3) Although the 340B program was initially targeted to a select group of hospitals, participation has swelled, owing to expanded eligibility in 2004 and 2010 and the program’s popularity.1

Effective January 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reduced Medicare reimbursement to physicians administering discounted drugs acquired by most 340B hospital participants.3 Opponents of reform contend that 340B revenues finance safety-net services,4 whereas supporters contend that most participants do not direct revenue back to safety-net care.5 We examined how uncompensated care, provision of low-profit services, and financial stability differed between nonprofit and public hospital 340B participants and nonparticipants in 2015.

Methods

We linked data from 1224 general acute care nonprofit and public hospitals from the Healthcare Cost Report Information System to 660 hospitals participating in the 340B program from the Health Resource & Services Administration’s provider list in 2015. Our sample was limited to urban hospitals with 100 or more beds that were not affected by eligibility expansions. The sample included nonprofit and public general acute-care hospitals that were not the target of direct eligibility expansions of 340B in 2010 or of indirect eligibility expansions of 340B eligibility through changes to the disproportionate-share hospital percentage adjustment in 2004. The sample excluded 115 hospitals that began participating in the program before 2015 but were no longer participating in 2015, 44 hospitals with missing data on the outcomes, and 21 observations representing more or less than 1 year. Owing to the use of publicly available data, the institutional review board of Vanderbilt University determined that the study was exempt from the need for review.

We compared 340B hospital participants with those that never participated with respect to their patient populations and US Census Bureau–reported community characteristics. We further divided participants into cohorts based on the date when they first registered for the program. We examined differences in uncompensated care, provision of low-profit services, and financial services from the hospitals’ cost reports using multivariable ordinary least-squares regressions with controls adjusting for differences in hospital and community characteristics. Stata, version 14.1 (StataCorp Inc) was used for the statistical analysis; differences are considered significant at P < .05.

Results

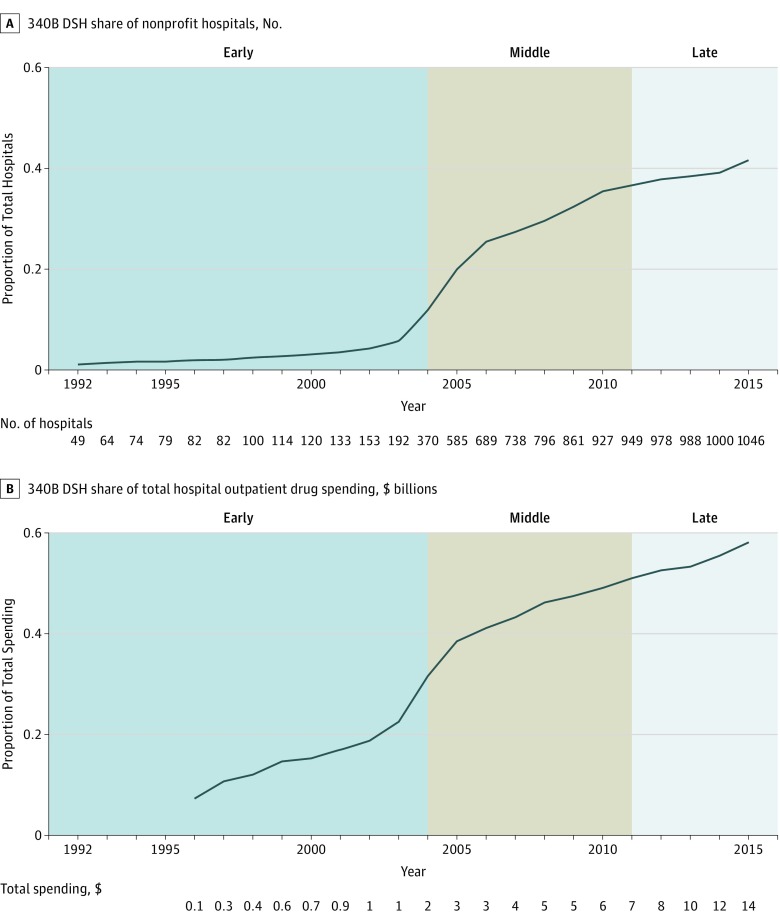

Before 2004 (early participants), fewer than 200 hospitals participated in the 340B program. From January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2010 (intermediate participants), participation increased to 927 hospitals, predominantly among hospitals not targeted by expansions. After 2010 (late participants), participation reached 1046 hospitals, or 41.8% of all 2504 nonprofit and public general acute care hospitals in 2015 (Figure). The 340B participants accounted for 60% ($14 billion) of hospital outpatient drug spending in 2015 nationwide (Figure). Important differences were noted between early and later participants in the 340B program. Early participants were larger (439 vs 338 beds), disproportionately public (81 [51.4%] vs 55 [11.0%]), academic (108 [67.9%] vs 91 [18.2%]), and located in counties with lower income levels (18% vs 15%) and higher levels of uninsured patients (14% vs 12%) when compared with intermediate and late participants (P < .001).

Figure. 340B Participation Among Nonprofit and Public General Acute Care Hospitals.

A, The graph illustrates the share of all nonprofit and public hospitals that are 340B disproportionate-share hospital (DSH) hospitals. B, The graph illustrates the share of all drug spending that originates in 340B institutions. The vertical lines divide the time series into cohorts of participants based on enactment of legislation plausibly affecting hospital finances before 2004 (early); from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2010 (intermediate); and after the enactment of the Medicare Modernization Act, 2011 or later, and after enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (late). Data are from the 1992-2015 Health Care Cost Report Information System and 340B Office of Pharmacy Affairs 304B provider database (N = 90 930). For both graphs, labeled data are the fraction expressed as a level.

In a comparison of all hospitals participating in the 340B program with nonparticipants in 2015, participants were less financial stable (−2.11% vs −1.74%; mean percentage point [PP] difference, 2.34%; 95% CI, −3.44% to −1.24%) and had slightly higher uncompensated care burden (4.10% vs 3.13%; mean adjusted PP difference, 0.08%; 95% CI, 0.38% to 1.26%) but were no more likely to offer low-profit services (48.18% vs 36.88%; mean adjusted PP difference, 5.33%; 95% CI, −0.54% to 11.21%) (Table).

Table. Adjusted Differences in Uncompensated Care, Low-Profit Service Provision, and Operating Margins Between 340B and Non-340B Disproportionate Share Hospitals Not Affected by Eligibility Expansionsa.

| Participation Cohort | Estimate (95% CI), %b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Marginc,d | Uncompensated Care Burdenc,e | Offers Low-Profit Servicesf | |

| Participants vs nonparticipants | −2.34 (−3.44 to −1.24) | 0.08 (0.38 to 1.26) | 5.33 (−0.54 to 11.21) |

| Cohort-specific differences | |||

| Early vs nonparticipants | −5.74 (−9.86 to −1.63) | 2.04 (1.21 to 2.87) | 8.79 (0.17 to 17.41) |

| Intermediate vs nonparticipants | −1.76 (−3.31 to −0.21) | 0.60 (0.22 to 0.98) | 5.88 (−1.46 to 13.21) |

| Late vs nonparticipants | −1.87 (−3.54 to −0.19) | 0.68 (0.14 to 2.62) | 2.17 (−7.62 to 11.96) |

Data are from the 2015 Healthcare Cost Report Information System and 340B Office of Pharmacy Affairs 304B Provider Database. Includes 340B participating (n = 660) and nonparticipating (n = 564) urban hospitals with 100 or more beds in 2015.

Derived from ordinary least-squares regressions controlling for hospital characteristics, including number of beds, measures of the county-level age distribution in 5-year age categories, academic status measured by 100 or more full-time resident equivalents, county-level poverty and uninsured rates, and state of location. Urban status and number of beds were reported by the hospital to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for reimbursement purposes through the Heathcare Cost Report Information System.

Adjusted for outlier values by winsorizing each outcome at the 5th and 95th percentiles.

Defined as the percentage of hospital revenue net of contractual allowance than can be retained as income.

Defined as the sum of hospital charity care and bad debt expenses divided by the hospital’s total expenses, including all uncompensated care provided by the hospital on its campus and not off-campus facilities.

Defined as operating an inpatient psychiatric facility or department or offering a burn care unit.

When we compared early participants with nonparticipants, the former spent more of their budget on uncompensated care (5.94% vs 3.13%; adjusted mean PP difference, 2.04%; 95% CI, 1.21% to 2.87%) and were more likely to offer low-profit services (62.89% vs 36.88%; adjusted mean PP difference, 8.79%; 95% CI, 0.17% to 17.41%) despite operating at a relative loss (−6.65% vs 2.11%; mean adjusted PP difference, −5.74%; 95% CI, −9.86% to −1.63%). Intermediate (3.59% vs 3.13%; mean adjusted PP difference, 0.60%; 95% CI, 0.22% to 0.98%) and late (3.31% vs 3.13%; mean adjusted PP difference, 0.68%; 95% CI, 0.14% to 2.62%) participants provided slightly more uncompensated care than did nonparticipants while operating at a relative loss (0.40% vs 2.11%; mean adjusted PP difference, −1.76%; 95% CI, −3.31% to −0.21%). However, neither intermediate (44.89% vs 36.88%; mean adjusted PP difference, 5.88%; 95% CI, −1.46% to 13.21%) nor late (39.53% vs 36.88%; mean adjusted PP difference, 2.17%; 95% CI, −7.62% to 11.96%) participants were more likely to offer low-profit services.

Discussion

As of 2015, 41.8% of all nonprofit and public general acute-care hospitals participated in the 340B program. Although participating hospitals provided more uncompensated care and low-profit services to patients despite worse finances than nonparticipants, later participants—most hospitals—spent less of their budget on uncompensated care and were more financially stable compared with earlier participants. Our results should be interpreted as descriptive owing to unmeasured confounding, and some of our outcome measures may be reported with error.6

Recent reimbursement reforms will likely have different effects across 340B participants. Targeting cuts might mitigate potential adverse effects on participants that provide a large amount of charitable medical care and operate at a substantial loss.

References

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: Overview of the 340B Drug Pricing Program. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/may-2015-report-to-the-congress-overview-of-the-340b-drug-pricing-program.pdf?sfvrsn=0. May 2015. Accessed July 21, 2017.

- 2.Mulcahy AW, Armstrong C, Lewis J, Mattke S. The 340B Prescription Drug Discount Program Origins, Implementation, and Post-Reform Future. RAND Corporation. 2014. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE121.html. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Program: Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment Systems and Quality Reporting Programs. Vol CMS-1678-P. https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2017-14883.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

- 4.American Hospital Association. Hospital Groups File Lawsuit to Stop Significant Payment Cuts for 340B Hospitals. https://www.aha.org/presscenter/pressrel/2017/111317-pr-340b-lawsuit.shtml. Accessed November 14, 2017.

- 5.Ross C. Trump takes on hospitals: the facts behind fight over 340B drug discounts. https://www.statnews.com/2017/11/06/340b-drug-discounts-fight/. November 6, 2017. Accessed December 31, 2017.

- 6.Kane NM, Magnus SA. The Medicare Cost Report and the limits of hospital accountability: improving financial accounting data. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2001;26(1):81-105. doi: 10.1215/03616878-26-1-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]