Abstract

Background

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) cause a considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide especially in children. However, there are few studies of the etiological structure of ARIs in Russia. In this work, we analyzed the etiology of ARIs in children (0–15 years old) admitted to Novosibirsk Children’s Municipal Clinical Hospital in 2013–2017.

Methods

We tested nasal and throat swabs of 1560 children with upper or lower respiratory infection for main respiratory viruses (influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza virus types 1–4, respiratory syncytial virus, metapneumovirus, four human coronaviruses, rhinovirus, adenovirus and bocavirus) using a RT-PCR Kit.

Results

We detected 1128 (72.3%) samples were positive for at least one virus. The most frequently detected pathogens were respiratory syncytial virus (358/1560, 23.0%), influenza virus (344/1560, 22.1%), and rhinovirus (235/1560, 15.1%). Viral co-infections were found in 163 out of the 1128 (14.5%) positive samples. We detected significant decrease of the respiratory syncytial virus-infection incidence in children with increasing age, while the reverse relationship was observed for influenza viruses.

Conclusions

We evaluated the distribution of respiratory viruses in children with ARIs and showed the prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus in the etiological structure of infections. This study is important for the improvement and optimization of diagnostic tactics, control and prevention of the respiratory viral infections.

Introduction

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) pose a significant public health problem worldwide, causing considerable morbidity and mortality among people of all age groups [1]. Children are on average infected two to three times more frequently than adults. [2]. There are more than 200 respiratory viruses that can cause ARIs. Human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV), human rhinovirus (HRV), human metapneumovirus (HMPV), human parainfluenza virus (HPIV), human enterovirus (EV), influenza virus (IFV), human coronavirus (HCoV), adenovirus (HAdV), and human bocavirus (HBoV) are the most common viral agents associated with ARIs, accounting for around 70% of ARIs [3, 4]. The frequency of mixed respiratory viral detection varies from 10% to 30% in hospitalized children [5–7]. In addition, several new human respiratory viruses have been described in recent years, including human metapneumovirus [8, 9], human bocavirus [10], and novel human coronaviruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [11], human coronaviruses NL63 (HCoV-NL63), HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1) [12], and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS—CoV) [13].

Although the majority of ARIs are associated with respiratory viruses, antibiotics are often used in the clinical treatment of ARIs. As children with ARIs often have similar clinical symptoms, studying the clinical hallmarks of children with virus-related ARIs and the spectrum of respiratory viruses will help in developing more accurate treatments for ARIs [14]. Rapid diagnosis is important not only for timely treatment starting but also for the detection of a beginning influenza epidemic and the avoidance of unnecessary antibiotic treatment [15, 16].

Western Siberia plays a key role in ecology, epizootiology and epidemiology of emerging diseases. This territory was involved in the circulation of A/H5N1 and A/H5N8 avian influenza viruses in 2005–2017 [17, 18]. These viruses were spread by wild birds’ migration. In Western Siberia migratory flyways of birds’ wintering in different regions of the world: South East Asia, Central Asia, Middle East, Hindustan, Europe, and Africa—cross. For this reason, there is high probability of the emergence of humans and animal influenza viruses reassortants, as well as emergence of local outbreaks of human morbidity caused by uncommon variants of influenza viruses. Furthermore, Novosibirsk is the largest transport hub in this part of Russia with numerous international connections, that is important for the spread of ARIs [19, 20].

The prevalence of respiratory viruses among children with ARIs differs in different regions and varies over time [21–25]. Thus, to better understand the epidemiology of Acute Respiratory Infections in Novosibirsk region, we investigated etiology of ARIs in children admitted to Novosibirsk Children’s Municipal Clinical Hospital in 2013–2017.

Materials and methods

Ethics issues

All aspects of the study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "Research Center of Clinical and Experimental Medicine" (2013–23). Accordingly, written informed consent was obtained from parents prior to sample taking.

Patients and specimens

Children 0-15years of age were enrolled in the study within 3 days of illness onset and had at least two of the following symptoms: fever, sore throat, cough, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, sputum, shortness of breath, lung auscultation abnormalities, tachypnea, and chest pain. Paired nasal and throat swabs were collected from each patient admitted to Novosibirsk Children’s Municipal Clinical Hospital by hospital nurses. A total of 1560 samples collected during four epidemic seasons of 2013–2017 (October–April) were enrolled to the study. The epidemiological and clinical information including case history, symptoms, physical signs, and examination were included in a standardized questionnaire. The samples were placed immediately in viral transport medium (Eagle MEM, BSA and antibiotics) and stored at 4–8°C prior transportation to the laboratory (not more than 24 hours). Detection of respiratory viruses was performed immediately after delivery to the laboratory. All specimens were tested for 15 common respiratory viruses, including influenza virus types A, B (IFVA and IFVB), human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) types 1–4, human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV), human metapneumovirus (HMPV), four human coronaviruses (HCo), human rhinovirus (HRV), human adenovirus (HAdV) and human bocavirus (HBoV), using a real-time PCR assay-kit.

Nucleic acid extraction and reverse transcription

Viral nucleic acids were extracted from nasal and throat swabs using RNA/DNA extraction kit «RIBO-sorb» (Interlabservice, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted viral nucleic acid was immediately used to perform the reaction of reverse transcription using commercial kit "REVERTA-L" (Interlabservice, Russia).

Virus detection

Detection of respiratory viruses, including HPIV 1–4, HRSV, HMPV, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoVNL63, HCoV-HKU1, HRV, HAdV, and HBoV was performed using a RT-PCR Kit «AmpliSens ARVI-screen-FL» (Interlabservice, Russia), and IFVA and IFVB virus detection was performed using a RT-PCR Kit « AmpliSens Influenza virus A/B-FL» (Interlabservice, Russia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Positive and negative controls were included in each run.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed chi-square test (two by two table) was performed to compare the infection rates for respiratory viruses among different age groups. P-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Totally, 1560 samples collected from patients with ARIs during the period from December 2013 to April 2017 were enrolled in the investigation. There were 824 males (52.8%) and 736 females (47.2%), and the patient’s ages ranged from 3 months to 15 years. The most numerous age group (43.2%) was between 1 and 3 years old. The age distribution is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics of 1560 children with ARIs in Novosibirsk Children’s Municipal Clinical Hospital from 2013 to 2017.

| Characteristics of the population | ARI (%)* Total N = 1560 |

Infected (%)** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total infection N = 1128 |

Single infection N = 965 |

Co-infection N = 163 |

|||

| Gender | Male | 824 (52.8) | 601 (72.9) | 504 (61.2) | 97 (11.7) |

| Female | 736 (47.2) | 527 (71.6) | 461 (62.6) | 66 (9.0) | |

| Age group (years) | < 1 | 325 (20.8) | 237 (72.9) | 194 (59.7) | 43 (13.2) |

| 1–3 | 674 (43.2) | 523 (77.6) | 436 (64.7) | 87 (12.9) | |

| 4–6 | 259 (16.6) | 201 (77.6) | 178 (68.7) | 23 (8.9) | |

| ≥ 7 | 302 (19.4) | 167 (55.3) | 157 (52.0) | 10 (3.3) | |

*- Proportion of each group in all the samples

**—Proportion of virus-positive samples in each gender or age group

Detection of respiratory viruses

Among 1560 samples, 1128 (72.3%) were found positive for at least one virus, and 432 (27.7%) were negative for all respiratory viruses tested (Table 1). There was no significant difference in the incidence of respiratory viral infection between boys (601/824; 72.9%) and girls (527/736; 71.6%) (χ2 = 0.345, p>0.05). The respiratory virus positive rate appeared to decrease with age. The lowest positive rate was observed in the age group of more than 6 years old (167/302; 55.3%), while the positive rates in age groups less than 6 years old were more than 70% (Table 1). Statistically significant difference was observed between the age group of more than 6 years old and other age groups (χ2 = 54.113, p<0.01). No statistically significant difference was observed among the age groups less than 1 year old, 1–3 years, and 4–6 years.

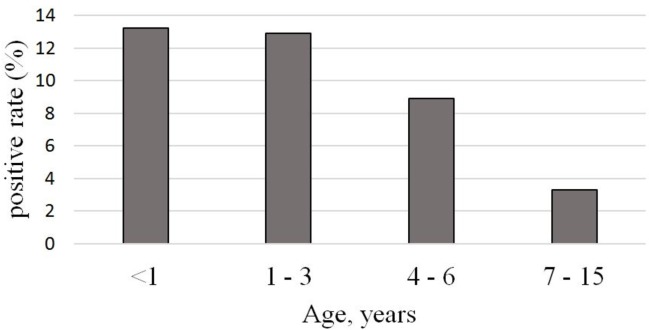

Among all the samples, single infections accounted for 61.9% (965/1560), while co-infections accounted for 10.4% (163/1560) with the lowest rate of incidence in children more than 6 years old compared to children younger than 6 years (χ2 = 20.389, p<0.01) (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Viral co-infection rate in different age groups.

Viral etiology

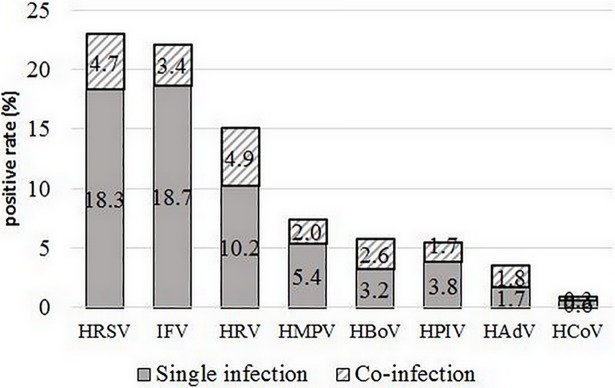

HRSV and IFV were the most frequently detected viruses with high incidence of 23.0% (358/1560) and 22.1% (344/1560), respectively, among all patients with ARIs. HRV was detected in 15.1% (235/1560), followed by HMPV, HPIV and HBoV with the detection rates higher than 5.0%. The positivity rates of HCoV and HAdV were lower than 5.0% (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Detection rates of viral pathogens in single and co-infections in children with ARIs (2013–2017).

Age and gender distribution

The data were analyzed with regard to the age and gender distribution of virus infection. No difference in the etiological distribution of viral pathogens was observed between males and females.

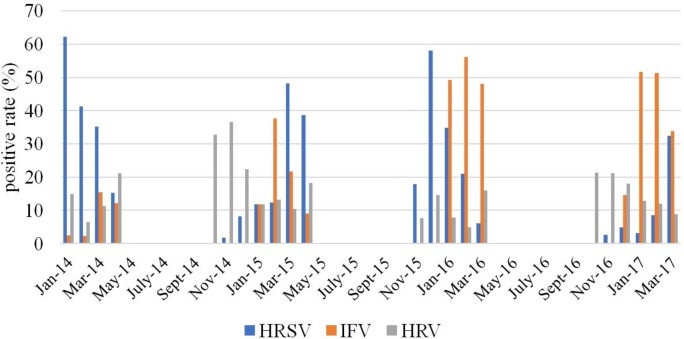

Among detected respiratory viruses, HRV, HPIV, HCoV, and HAdV did not have statistically significant difference in the distribution among the different age groups. HMPV was detected in age group less than 1 year old much more frequently than in children 1–3 years old (χ2 = 4.986, p<0.05) and 7–15 years old (χ2 = 8.174, p<0.05). HBoV was significantly more frequently observed in children younger than 3 years old compare with children of 4–15 years old (χ2 = 28.523, p<0.005). The incidence of HRSV decreased significantly with increasing age (p < 0.05) dropping from 35.1% in children younger than 1 year old to 5.3% in the school-age children (7–15 years old group), while the reverse relationship was observed for IFV (Fig 3).

Fig 3. The distribution of respiratory viruses in different age groups.

Seasonal distribution

The data were analyzed with regard to the seasonality. Overall, virus detection positive rate did not differ significantly between seasons, ranging from 71.3% to 73.3%. Fig 4 illustrates the monthly distribution of the most frequently detected viruses (HRSV, HRV and IFV) from 2013 to 2017. We have observed no considerable activity of Influenza viruses in 2013–2014 epidemic season, but increasing activity detected in subsequent years with peaks in February 2015, February 2016 and January and February 2017. HRSV exhibited marked peaks during each season: in January 2014, March 2015, December 2015 and March 2017. For HRV monthly distribution was relatively constant with only one clear peak in October–November 2014 (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Monthly distribution of HRSV, HRV and IFV.

Multiple infections

Co-infections with two or more viruses were detected in 163 out of the 1128 (14.5%) positive samples (Table 1). Dual infections accounted for 11.4% (129/1128) of all positive samples and three viruses were detected in 3.1% (34/1128) of positive samples. Most co-infected patients were 0–6 years of age (12.2%, 153/1258) versus children older than 6 years (3.4%, 10/292). No significant difference was found for incidence of co-infections between the age group less than 1 year (13.2%, 43/325), 1–3 years (12.9%, 87/674), and 4–6 years (8.9%, 23/259). The most common combinations were HRSV/HRV, and IFV/HRSV, which amounted to 13.5% (22/168) and 12.3% (20/163) of all cases of co-infection respectively. Co-infection rate of each individual virus detected varied significantly. DNA viruses, HAdV and HBoV, most often appeared in co-infections, with 52.7% (29/55) of adenovirus detection and 45.1% (41/91) of bocavirus detection. HRV was the most often co-infected with HBoV (34.1%, 14/41) and HAdV (31%, 9/29). We have not detected any case of simultaneous infection of HAdV and HBoV. All occurring combinations of viruses are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Detection of single and co-infection cases among 1560 children with ARIs in Novosibirsk Municipal Clinical Hospital from 2013 to 2017.

| Virus detected | IFV | HRSV | HRV | HPIV | HMpV | HCoV | HAdV | HBoV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFV | 291 | 20 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| HRSV | 285 | 22 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |

| HRV | 158 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 9 | 14 | ||

| HPIV | 60 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||

| HMpV | 84 | 0 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| HCoV | 9 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| HAdV | 26 | 0 | ||||||

| HBoV | 50 | |||||||

| Dual infections | 50 | 66 | 66 | 24 | 27 | 4 | 22 | 35 |

| Triple infections | 3 | 7 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Total | 344 | 358 | 235 | 87 | 115 | 13 | 55 | 91 |

Influenza viruses in etiology of ARIs

IFV was one of the most frequently detected viruses among children with ARIs with detection rate 22.1% (344/1560). The lowest detection rate of IFV was in the less than 1 year old age group (5.8%, 19/325). The incidence of IFV increased significantly with increasing patients’ age (p-value < 0.0001) showing 32.6% (183/561) in children older than 3 years.

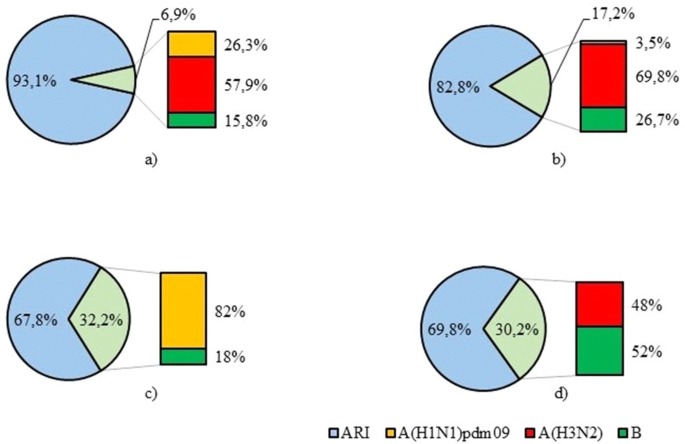

During the study period the lowest influenza activity was investigated in 2013–2014 with positivity rate 6.9% of all positive samples. In 2014–2015 influenza virus detection was 17.2% while in 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 the detection rates were much higher and amounted to 32.2% and 30.2% respectively. Influenza А(H3N2) virus was predominant in 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 accounting for 57.9% and 69.8% of all influenza virus detections while in 2015–2016 82% of influenza viruses were A(H1N1)pdm09. We did not reveal any influenza А(H3N2) viruses during 2015–2016 epidemic season. In 2016–2017 influenza type B detections (52%) predominating over type A (48%). Of influenza A viruses, all of them were A(H3N2) viruses (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Distribution of influenza A and B viruses in 2013–2017. a) 2013–2014 epidemic season. b) 2014–2015 epidemic season. c) 2015–2016 epidemic season. d) 2016–2017 epidemic season.

Discussion

Acute respiratory infections are a serious health and economic problem, causing high morbidity and significant economic losses due to temporary disability payments and medical costs. Children are the most vulnerable group to the development of the disease. As several authors mentioned previously [26], ARIs can lead to serious diseases such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia and sometimes even cause death in infants and children worldwide. Nevertheless, most of the data on the epidemiological features and etiological structure of ARIs were from more-developed countries, and less is known about the etiology of ARIs in Russia. In the present study, we examined the viral etiology of ARIs in hospitalized children in Novosibirsk by Real-Time RT-PCR assay.

We detected at least one of the tested viruses in 72.3% (1128/1560) of the samples. In similar studies conducted in different regions of the world, the virus detection rate ranged from less than 50% to 75% [27–29]. For example, in studies performed in China, the proportion of positive samples in children with ARIs ranged from 37.6% to 78.7% [15, 17, 30, 31]. The previous study of respiratory infections among children in European part of Russia revealed the 71.5% detection rate of respiratory viruses [32].

The percentage of the respiratory viruses’ detection varies in different years in different regions, which may be associated with climatic and environmental factors, population distribution, economic status and diagnostic methods used [1]. In addition, seasonality of sampling can also lead to differences in the level of viruses’ detection in various studies. Thus, Ju X. et al. carried out a study continuously from July 2011 through July 2013 and found 48.66% of samples to be positive for at least one respiratory virus [33]. In contrast, we collected samples only during epidemic seasons of ARIs, so the positivity rate in our study was considerably higher. Furthermore, acute respiratory infections can be caused by viruses that are not yet known, as well as bacteria that have not been included in these studies [14].

We found that the prevalence of respiratory viruses did not differ between boys and girls (72.9% and 71.6% respectively), which confirms the absence of a gender-based susceptibility to respiratory viral infections [14]. However, we observed a decrease in the respiratory viruses’ detection rate with age, with the lowest detection rate in school-age children compared to children under 7 years of age (55.3% versus 76.4%, respectively). These data are consistent with findings obtained in other regions of Russia [32] and it may be due to decreased sensitivity to respiratory virus infections in older children.

Etiology of ARIs and the respiratory virus prevalence varies in different studies. In the United States, IFV, HRSV and HPIV were the most frequently detected [34]. Studies conducted in France have shown that metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus are the most common [35]. IFV, HRSV and HRV were the most commonly detected respiratory viruses among children with ARIs in most regions of China [14]. The study of ARIs etiologic structure showed that HRSV, HRV, HPIV and IFV were registered significantly often among children in western part of Russia [32].

In our study the most common viruses detected were HRSV and IFV, followed by HRV. The age distribution of ARIs indicated that children under 3 years old were more likely to be infected by HRSV confirmed the importance of RSV in children with ARIs, especially in children < 4 years of age [36–39]. We observed a high rate of HRSV-detections in 2013–2014 (44.4%), while in 2016–2017 it was less than 10% which could be due to the annual variation in the circulation pattern of HRSV. Such year-to-year variation in the epidemiological patterns of viral infections confirms importance of the long-term study of the ARIs epidemiology [40].

Influenza virus is one of the major causative agents of respiratory disease in humans and may lead to serious illness [41]. In temperate countries influenza outbreaks usually occur during the winter season. Finally, in our study, IFV (344/1560, 22.1%) was the second most frequent detected pathogen with markable seasonality in winter months. During the 2013–2014 epidemic season, influenza virus detection rate was low—6.9% of all respiratory viruses, which was in accordance with the official influenza surveillance results of Ministry of Health, Russia [42]. In our study in 2014–2015, influenza viruses were detected in 17.2% among all respiratory viruses. Among those, the percentage of influenza A virus accounted for 73.3% and influenza B virus made up 26.7% of all detected influenza viruses. At the same time, in Russia influenza B was the main etiological agent, accounting for 50.6% of all detected influenza viruses. In 2015–2016, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus was predominant in Russia, accounting for 79% of all influenza-positive samples consistent with our results (82%). In 2016–2017 influenza A(H3N2) virus was dominant in Russia detected in 61.3% of all influenza virus cases [42]. In our study influenza A and B viruses were detected with approximately the same frequency (48% and 52% respectively).

With the introduction of molecular techniques, the detection of multiple co-infecting viruses has become common, though the prevalence of each virus varies between studies [43]. In our study detection rate of viral co-infection was 14.5% among the positive samples. According to the previous reports, the incidence of viral co-infection in children can reach 30% [44]. Co-infection is most often found in children under the age of 5, due to the immaturity of the immune system and, thus, greater susceptibility to infection [45]. In our study, we significantly more frequently detected cases of simultaneous infection with two or more viruses in children under 7 years of age compared with children of school age (12.2% versus 3.4%), while there was no significant difference in the incidence of viral co-infection between the age groups of 0–1 year, 1–3 years and 4–6 years.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in our study we investigated the etiological structure of acute respiratory viral infections in hospitalized children in Novosibirsk, Russia, and evaluated age and seasonal distribution of the various respiratory viruses. Systematic monitoring of respiratory viruses is necessary to better understand the structure of respiratory infections. Such studies are important for the improvement and optimization of diagnostic tactics, as well as measures for the control and prevention of the respiratory viral infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank the clinicians of Novosibirsk Children’s Municipal Clinical Hospital for their assistance with sample collection. We thank Dr. Galina Skosyreva and Elena Timofeeva (Department of propaedeutic of childhood diseases, Novosibirsk State Medical University, Novosibirsk, Russia) for their assistance with sample collection.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by a grant of Russian Scientific Foundation (project # 17-44-07001). KSh research activities have been supported by this grant. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wang H, Zheng Yu, Deng J, Wang W, Liu P, Yang F, et al. Prevalence of respiratory viruses among children hospitalized from respiratory infections in Shenzhen, China. Virol J. 2016; 13:39 10.1186/s12985-016-0493-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams BG, Gouws E, Boschi-Pinto C, Bryce J, Dye C. Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002; 2:25–32; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kusel MM, de Klerk NH, Holt PG, Kebadze T, Johnston SL, Sly PD. Role of respiratory viruses in acute upper and lower respiratory tract illness in the first year of life: a birth cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006; 25:680–686; 10.1097/01.inf.0000226912.88900.a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brittain-Long R, Nord S, Olofsson S, Westin J, Anderson LM, Lindh M. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of respiratory tract infections. J Clin Virol. 2008; 41:53–56; 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu Y, Wang S, Zhang L, Xu C, Bian C, Wang Z, et al. Epidemiology of human respiratory viruses in children with acute respiratory tract infections in Jinan, China. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013; 2013:210490 10.1155/2013/210490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sentilhes AC, Choumlivong K, Celhay O, Sisouk T, Phonekeo D, Vongphrachanh P, et al. Respiratory virus infections in hospitalized children and adults in Lao PDR. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013; 7(6):1070–78; 10.1111/irv.12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tecu C, Mihai ME, Alexandrescu VI, Orăşeanu D, Zapucioiu C, Ivanciuc AE, et al. , Single and multipathogen viral infections in hospitalized children with acute respiratory infections. Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol. 2013; 72(4), 242–9; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, Kuiken T, de Groot R, Fouchier RA, et al. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med. 2001. June;7(6):719–24; 10.1038/89098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feuillet F, Lina B, Rosa-Calatrava M, Boivin G. Ten years of human metapneumovirus research. J Clin Virol. 2012. February;53(2):97–105. 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.10.002 Epub 2011 Nov 9; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005. September; 102(36):12891–6. Epub 2005 Aug 23. 10.1073/pnas.0504666102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003. May 15;348(20):1967–76. Epub 2003 Apr 10; 10.1056/NEJMoa030747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pyrc K, Berkhout B, van der Hoek L. The novel human coronaviruses NL63 and HKU1. J Virol. 2007 Apr;81(7):3051–7. Epub 2006 Nov 1; 10.1128/JVI.01466-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman CM, Frieman MB. Coronaviruses: Important Emerging Human Pathogens. J Virol. 2014. May;88(10):5209–12. 10.1128/JVI.03488-13 Epub 2014 Mar 5; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong W, Chen Q, Hu Y, He D, Liu J, Yan H. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of respiratory viral infections in children in Shanghai, China. Arch Virol. 2016. July;161(7):1907–13. 10.1007/s00705-016-2866-z Epub 2016 May 2; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper SA, Bradley JS, Englund JA, File TM, Gravenstein S, Hayden FG, et al. Seasonal influenza in adults and children—diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 48:1003–32. 10.1086/598513 ; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low D. Reducing antibiotic use in influenza: challenges and rewards. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008. April; 14(4):298–306. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01910.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharshov K, Romanovskaya A, Uzhachenko R, Durymanov A, Zaykovskaya A, Kurskaya O, Ilinykh P, Silko N, Kulak M, Alekseev A, Zolotykh S, Shestopalov A, Drozdov I. Genetic and biological characterization of avian influenza H5N1 viruses isolated from wild birds and poultry in Western Siberia. Arch Virol. 2010. July; 155(7):1145–1150; 10.1007/s00705-010-0676-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee DH, Sharshov K, Swayne DE, Kurskaya O, Sobolev I, Kabilov M, Alekseev A, Irza V, Shestopalov A. Novel Reassortant Clade 2.3.4.4 Avian Influenza A(H5N8) Virus in Wild Aquatic Birds, Russia, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017. February; 23(2):359–360. 10.3201/eid2302.161252 Epub 2017 Feb 15; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilyicheva T, Sobolev I, Susloparov I, Kurskaya O, Durymanov A, Sharshov K, Shestopalov A. Monitoring of influenza viruses in Western Siberia in 2008–2012. Infect Genet Evol. 2013. December; 20:177–87. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.08.025 Epub 2013 Sep 5; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Marco MA, Delogu M, Sivay M, Sharshov K, Yurlov A, Cotti C, Shestopalov A. Virological evaluation of avian influenza virus persistence in natural and anthropic ecosystems of Western Siberia (Novosibirsk Region, summer 2012). PLoS One. 2014. June 27; 9(6): e100859 10.1371/journal.pone.0100859 eCollection 2014; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang G, Hu Y, Wang H, Zhang L, Bao Y, Zhou X. High incidence of multiple viral infections identified in upper respiratory tract infected children under three years of age in Shanghai, China. PLoS One. 2012; 7(9):e44568 10.1371/journal.pone.0044568 Epub 2012 Sep 7; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang G, Yu D, Mao N, Zhu Z, Zhang H, Jiang Z, et al. Viral etiology of acute respiratory infection in Gansu Province, China, 2011. PLoS One. 2013. May 14;8(5): e64254 10.1371/journal.pone.0064254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai XY, Wang Q, Lin GY, Cai ZW, Lin CX, Chen PZ, et al. Respiratory virus infections among children in South China. J Med Virol. 2014. July; 86(7):1249–55. 10.1002/jmv.23931 Epub 2014 Mar 12; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter J, Panayiotou C, Tryfonos C, Koptides D, Koliou M, Kalogirou N, et al. Aetiology of Acute Respiratory Tract Infections in Hospitalised Children in Cyprus PLoS One. 2016. January 13; 11(1): e0147041 10.1371/journal.pone.0147041 eCollection 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khor CS, Sam IC, Hooi PS, Quek KF, Chan YF. Epidemiology and seasonality of respiratory viral infections in hospitalized children in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: a retrospective study of 27 years. BMC Pediatr. 2012. March 20; 12:32 10.1186/1471-2431-12-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsukagoshi H, Ishioka T, Noda M, Kozawa K, Kimura H. Molecular epidemiology of respiratory viruses in virus-induced asthma. Front Microbiol. 2013. September 12;4:278 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierangeli A, Gentile M, Di MP, Pagnotti P, Scagnolari C, Trombetti S, et al. Detection and typing by molecular techniques of respiratory viruses in children hospitalized for acute respiratory infection in Rome, Italy. J Med Virol. 2007; 79:463–8. 10.1002/jmv.20832 ; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hombrouck A, Sabbe M, Van Casteren V, Wuillaume F, Hue D, Reynders M, et al. Viral aetiology of influenza-like illness in Belgium during the influenza A(H1N1)2009 pandemic. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012. June;31(6):999–1007. 10.1007/s10096-011-1398-4 Epub 2011 Sep 8; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlaudecker EP, Heck JP, Macintyre ET, Martinez R, Dodd CN, McNeal MM, et al. Etiology and seasonality of viral respiratory infections in rural Honduran children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012; 31:1113–8. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31826052eb ; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng J, Kong W, Guo D, Liu M, Wang Y, Zhu H, et al. The epidemiology and etiology of influenza-like illness in Chinese children from 2008 to 2010. J Med Virol. 2012. April; 84(4):672–8. 10.1002/jmv.22247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Wei Q, Tan A, Wang L. Epidemiological analysis of respiratory viral etiology for influenza-like illness during 2010 in Zhuhai, China. Virol J. 2013. May 7; 10:143 10.1186/1743-422X-10-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lvov NI, Pisareva MM, Maltsev OV, Buzitskaya JV, Afanasieva VS, Mikhailova MA, et al. [The features of ARVD etiological structure in different age and professional population groups in Saint-Petersburg during 2013–2014 epidemic season]. Journal of Infectology. 2014; 6(3): 62–70. Russian; [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ju X, Fang Q, Zhang J, Xu A, Liang L, Ke C. Viral etiology of influenza-like illnesses in Huizhou, China, from 2011 to 2013. Arch Virol. 2014. August; 159(8):2003–10. 10.1007/s00705-014-2035-1 Epub 2014 Mar 9; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hasman H, Pachucki CT, Unal A, Nguyen D, Devlin T, Peeples ME, et al. Aetiology of influenza-like illness in adults includes parainfluenzavirus type 4. J Med Microbiol. 2009. April; 58(Pt 4):408–13. 10.1099/jmm.0.006098-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falchi A, Turbelin C, Andreoletti L, Arena C, Blanchon T, Bonmarin I, et al. Nationwide surveillance of 18 respiratory viruses in patients with influenzalike illnesses. A pilot feasibility study in the French Sentinel network. J Med Virol. 2011. August; 83(8):1451–7. 10.1002/jmv.22113 Epub 2011 Jun 2; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Do AH, van Doorn HR, Nghiem MN, Bryant JE, Hoang TH, Do QH, et al. Viral etiologies of acute respiratory infections among hospitalized Vietnamese children in Ho Chi Minh City, 2004–2008. PLoS One. 2011. March 24; 6(3): e18176 10.1371/journal.pone.0018176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He Y, Lin GY, Wang Q, Cai XY, Zhang YH, Lin CX, et al. A 3-year prospective study of the epidemiology of acute respiratory viral infections in hospitalized children in Shenzhen, China Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2014. July; 8(4):443–51. 10.1111/irv.12257 Epub 2014 May 14; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurgel RQ, Bezerra PG, Duarte Mdo C, Moura AÁ, Souza EL, Silva LS, et al. Relative frequency, Possible Risk Factors, Viral Codetection Rates, and Seasonality of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Among Children With Lower Respiratory Tract Infection in Northeastern Brazil. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016. April; 95(15): e3090 10.1097/MD.0000000000003090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Homaira N, Luby SP, Hossain K, Islam K, Ahmed M, Rahman M, et al. Respiratory Viruses Associated Hospitalization among Children Aged< 5 Years in Bangladesh: 2010–2014. PLoS One. 2016. February 3;11(2): e0147982 10.1371/journal.pone.0147982 eCollection 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delangue J, Roca Sanchez Y, Piorkowski G, Bessaud M, Baronti C, Thirion-Perrier L, et al. Viral aetiology influenza like illnesses in Santa Cruz, Bolivia (2010–2012). Virol J. 2014. February 24;11:35 10.1186/1743-422X-11-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005. November; 5(11):718–25; 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70270-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.rospotrebnadzor.ru [Internet]. On the outcome of the epidemic season of influenza and ARIs [cited 2018 June 3]. Available from: http://www.rospotrebnadzor.ru/deyatelnost/epidemiological-surveillance/;

- 43.Cebey-López M, Herberg J, Pardo-Seco J, Gómez-Carballa A, Martinón-Torres N, Salas A, et al. Viral Co-Infections in Pediatric Patients Hospitalized with Lower Tract Acute Respiratory Infections. PLoS One. 2015. September 2; 10(9): e0136526 10.1371/journal.pone.0136526 eCollection 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asner SA, Science ME, Tran D, Smieja M, Merglen A, Mertz D. Clinical Disease Severity of Respiratory Viral Co-Infection versus Single Viral Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2014. June 16; 9(6): e99392 10.1371/journal.pone.0099392 eCollection 2014; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huo X, Qin Y, Qi X, Zu R, Tang F, Li L, et al. Surveillance of 16 respiratory viruses in patients with influenza-like illness in Nanjing, China. J Med Virol. 2012. December; 84(12):1980–4. 10.1002/jmv.23401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.