Abstract

Introduction:

Research has often been viewed as a passive process by which participants enroll in studies developed by researchers. It is becoming clearer that to understand the nuances of mood episodes and how to prevent them, we need to conduct large clinical trials that have the power to investigate moderators and mediators, or catalysts and mechanisms of change. MoodNetwork, the first online, patient-centered research community for individuals with mood disorders, aims to change the way that traditional research has been conducted by involving patients, their caregivers, and advocates in the process of research. The aim of this report is to share lessons learned from developing MoodNetwork.

Methods:

Participants enroll by completing a demographic survey and consent form. Once enrolled, participants are encouraged to complete optional surveys about their mood disorders and areas of research priority. Stakeholder and advocacy partners developed the website, web-based surveys, and recruitment materials.

Results:

MoodNetwork has enrolled 4103 participants to date. Of this sample, 96.9% report experiencing depression and 79.7% endorse symptoms of mania or hypomania. Participants rated reducing stigma and alleviating symptoms as their 2 largest research priorities. Recruitment has been slower than expected. Recruiting a diverse sample has been challenging, and this impacts the Network’s ability to conduct comparative effectiveness research studies.

Discussion:

We discuss lessons learned from recruiting individuals with mood disorders to MoodNetwork, an innovative approach to conducting clinical trials. We identify and review 5 strategies for increasing enrollment as well as future directions.

Key Words: MoodNetwork, mood disorders, patient-centered

One in 5 adults has a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder, ∼17% (12% for men and 25% for women) of whom are diagnosed with major depressive disorder and 2%–4% with bipolar disorder.1–3 The yearly costs of depression and bipolar disorder in the United States are $100 billion and $151 billion, respectively.4,5 Mood disorders are associated with decreased earnings,6 increased use of health care for other medical conditions, and premature death.7,8 Mood disorders can be chronic and difficult to treat; even after multiple, sequential interventions, only 50% of those with depression9 and 30% with bipolar disorder10 achieve remission.

Clinical research investigating interventions, such as those designed to treat mood disorders and other mental health conditions, has traditionally been conducted through carefully controlled trials.11 However, typical research trials are limited in their ability to generalize findings to the larger population due to study restrictions, such as limited inclusion and extensive exclusion criteria and geographical limitations.12 Such studies often do not allow for comparative arms that are representative of a real clinical care setting, or they examine outcomes that the patients in the population under study do not find helpful or want prioritized.11,13 Patient-centered methodological approaches, such as comparative effectiveness research, allow researchers to address this inability to generalize studies while also including patients with expertise through experience in the research process.14

MoodNetwork is an innovative approach to conducting clinical research for mood disorders that is designed to address typical research trial barriers. It is a collaboration of clinicians, researchers, patients, caregivers, and other advocates that form an online community designed to conduct comparative effectiveness research on mood disorders. MoodNetwork aims to address the difficulties in treating mental health conditions by giving individuals an opportunity to openly discuss their conditions, challenge the stereotypes associated with mental illness, and suggest clinical practices and research topics. By bringing together a large, diverse group of individuals with mood disorders interested in focusing on patient-reported outcomes and patient priorities in research, MoodNetwork has the potential to identify and investigate the factors that are of most importance to study participants. The primary aim of this report is to share lessons learned from developing MoodNetwork; a secondary aim is to examine trends in enrollment and discuss future directions for the Network.

METHODS

Participants

IRB approval was obtained before beginning the study. As of June 1, 2017, MoodNetwork has enrolled 4103 participants between the ages of 18 and 86. Online informed consent was obtained before collecting any study information. Participants were excluded if they were under the age of 18.

Procedure

The founders of MoodNetwork collaborated with clinicians, researchers, patients, caregivers, and key patient advocacy groups to develop a website that promotes inclusion, equality, and a balanced perspective on mood disorders. Patient stakeholders from various backgrounds serve on MoodNetwork’s team, including leaders from the International Bipolar Foundation (IBPF), Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA), Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA), National Organization for People of Color Against Suicide (NOPCAS), and National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). These stakeholder and advocacy group members developed the website, web-based surveys, and recruitment materials with the goal of reducing stigma and maximizing the generalizability of content to participants with mood disorders.

Assessments

When participants enroll in MoodNetwork, they provide demographic information, such as race, ethnicity, age, marital status, and sex. Once enrolled, participants are able to complete several types of tools and surveys. These include a research priorities survey, which asks participants to select research topics that are of importance to them, as well as questionnaires designed to help track mood. In addition to questionnaire data, qualitative data are collected from MoodNetwork forums, which serve as a portal for open discussions for all MoodNetwork participants.

RESULTS

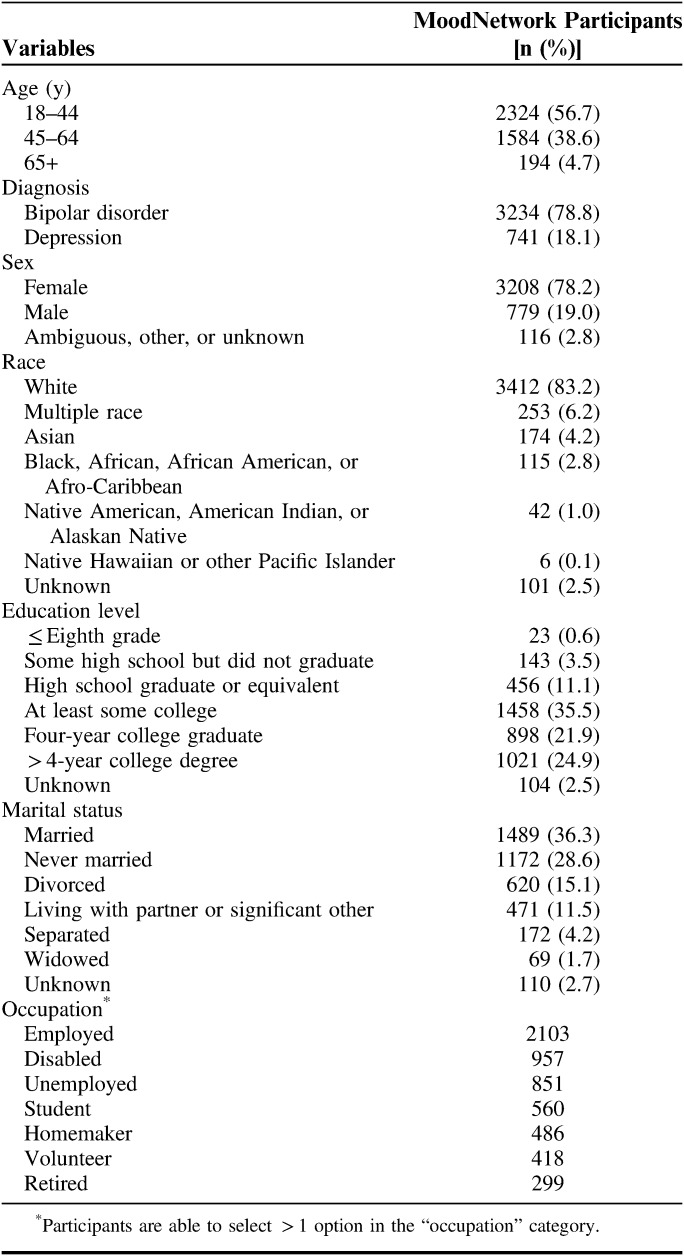

Most (96.9%) MoodNetwork participants report experiencing depression at some point in their lives, and 79.7% endorse past episodes of mania or hypomania. The mean age of participants is 42 (SD=13.0; range, 18–86). The majority of the sample is female (78.2%), with 19.0% being male, 0.5% ambiguous sex, and 2.3% other or unknown (Table 1). The MoodNetwork sample consists of mostly white participants (83.2%).

TABLE 1.

MoodNetwork Participant Demographics

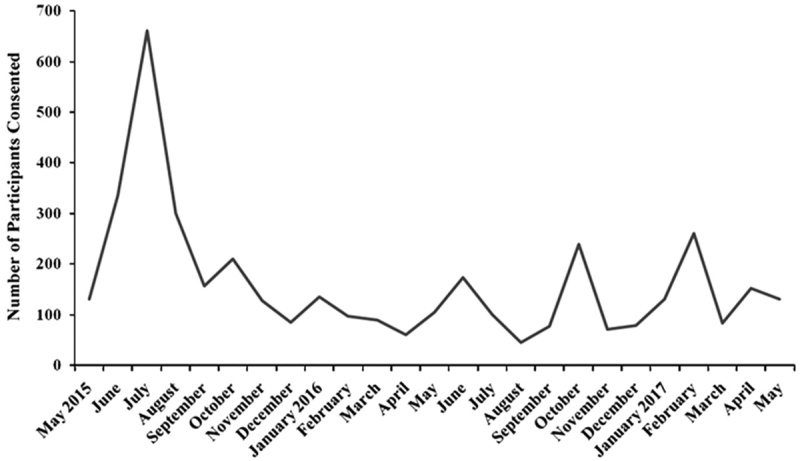

Figure 1 shows enrollment over time for MoodNetwork. After an initial spike in recruitment in the first 60 days (10 participants/d) as individuals from our advocacy partners joined, enrollment has been steady (5 participants/d).

FIGURE 1.

MoodNetwork enrollment per month (2015–2017).

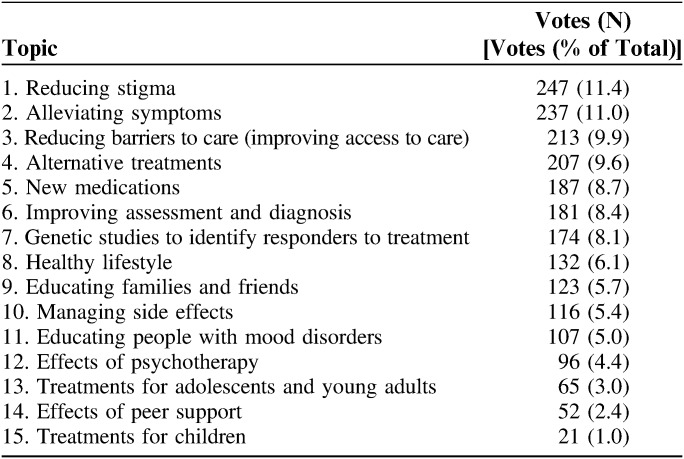

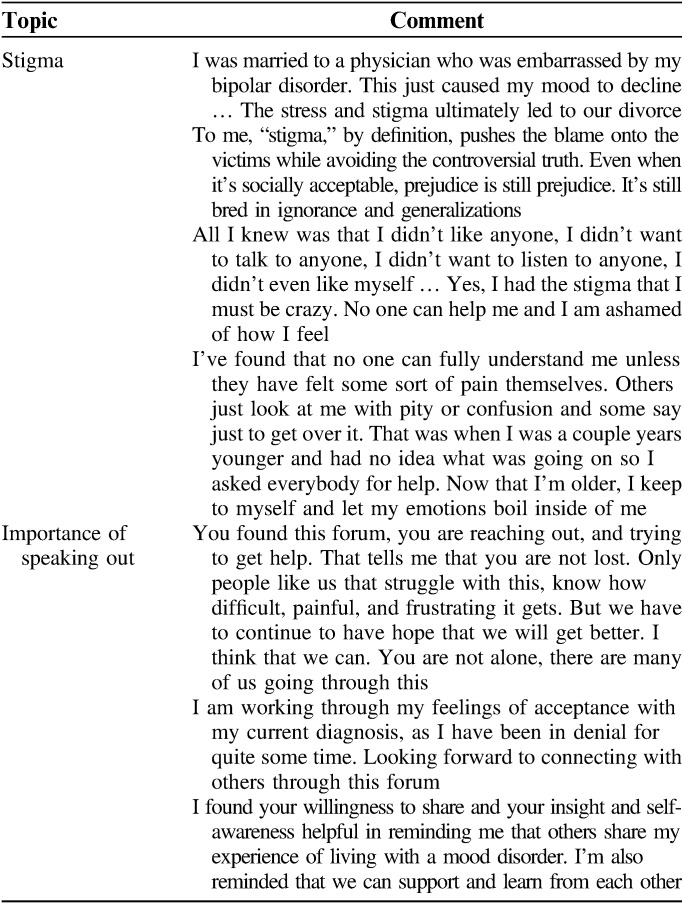

The 3 most important research topics voted on by participants are reducing stigma (11.4% of votes), alleviating symptoms (11.0%), and reducing barriers to care (9.9%; Table 2). Participants provide qualitative data with their forum responses, such as through comments on stigma and their loneliness in living with these conditions (Table 3). Stakeholders involved in the study help generate strategies to address gaps brought up by qualitative feedback (forums) and quantitative responses (surveys), which include strategies that they perceive as key to reducing stigma and increasing enrollment within the MoodNetwork community. Using the “research priorities” survey, MoodNetwork participants and stakeholders have prioritized mental health stigma, an issue that continues to be a national and global problem and impacts the treatment and research of mood disorders.

TABLE 2.

Preferred Research Topics for MoodNetwork

TABLE 3.

Selected Qualitative Feedback From MoodNetwork Participants

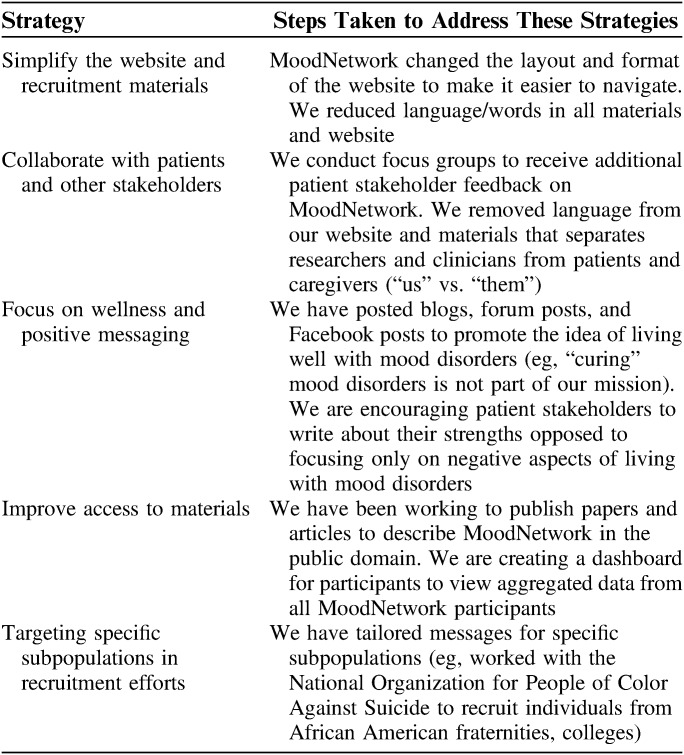

The 5 main strategies that may help facilitate recruitment to MoodNetwork and other online programs that adopt this innovative approach to research are: (1) simplifying the language of the website and recruitment materials; (2) removing messaging that separates researchers and clinicians from patients and caregivers (“us” vs. “them”); (3) focusing on wellness and positive messaging; (4) improving access to materials developed by MoodNetwork and its collaborators by widely disseminating them through our advocacy partners; and (5) targeting recruitment toward specific subpopulations to increase their representation (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Strategies for Reducing Stigma and Encouraging People to Speak Out

DISCUSSION

MoodNetwork has recruited a relatively large sample (ie, over 4000) of individuals with mood disorders to provide longitudinal patient-reported outcomes. Consistent with other online registries, 78.2% of participants are female. In addition, 78.8% have self-reported bipolar disorder rather than major depressive disorder, and racial and ethnic diversity are limited. The underrepresentation of these populations is explained by previous research indicating that minority populations and men are less likely to seek care for mental health conditions.15–17

MoodNetwork’s original recruitment goal was to enroll a community of 20,000 individuals with mood disorders. We are underenrolled, and progress toward this goal has been slower than anticipated. Our enrollment data, stakeholder input, and research priorities suggest that new strategies that target minority groups and individuals with depression could bolster recruitment for MoodNetwork, especially because a necessary component of this innovative research approach is generalizability to all people with mood disorders. In addition, participants indicate how they heard about the Network when they first register for the community. We use these data to focus our recruitment efforts on common referral sources.

As evidenced by participants’ research priorities, decreasing stigma is an important future direction for MoodNetwork. Stigma surrounding mental health conditions has been linked to increased depression, poorer quality of life, low self-esteem, and fewer employment opportunities.18–20 Moreover, in our effort to build MoodNetwork, we have consistently received feedback that people are nervous to join, as they do not want to be affiliated with a Network about mood disorders. Thus, MoodNetwork has realized that, to continue to embrace an innovative approach to patient-centered research, we must focus on reducing the stigma surrounding mood disorders.

On the basis of input from our stakeholders, MoodNetwork identified 5 strategies to reduce stigma within the MoodNetwork community (Table 4). We believe that a focus on increasing the diversity of MoodNetwork will help reduce stigma by creating an open community that represents the universal nature of mood disorders. In representing a diverse community of individuals with mood disorders to both potential participants and current participants, MoodNetwork will communicate the important message that no person is alone in his or her diagnosis. MoodNetwork has worked closely with its stakeholder partners to use these strategies. For example, patients with depression or bipolar disorder often have difficulties with concentration, focus, and retention of details. To address this, we streamlined language throughout the MoodNetwork website to ensure that it is presented in small, easy-to-read chunks. We worked closely with our patient partners to determine the best way to present information to the specific population studied by MoodNetwork. We also keep all video material <5 minutes long. To promote a collaborative research environment, we ask patient partners what they want MoodNetwork to focus on in future research projects (Table 3). We also focus on and promote using positive language that describes living well with mood disorders as opposed to calling these conditions illnesses or saying that people with these conditions need to be cured. Finally, MoodNetwork plans on making aspects of the website that are currently for members only, such as surveys and feedback, available to the public or any visitor of MoodNetwork (before signing up or enrolling), as our stakeholders believe that this is key to building trust in the MoodNetwork team and project and encouraging more participants to enroll.

Perhaps most noteworthy, we have shifted our focus from large-scale, general messaging to “get everyone” with a mood disorder to targeting specific subpopulations, such as African American male fraternities, individuals with unipolar depression, and men through the Australian men’s network. This strategy has helped improve recruitment of both men and members of minority groups, but given that we are targeting smaller groups of people, these campaigns tend to bring in fewer participants. However, recognizing and understanding that stigma and anxiety surrounding mood disorders could be contributing to slower enrollment, our team of stakeholders, patient partners, clinicians, and researchers feels that we need targeted, meaningful, patient-centered messaging to create trust and promote understanding of MoodNetwork’s mission.

MoodNetwork is actively working with its stakeholders and participants to create a community of individuals with mood disorders to participate in comparative effectiveness research. We hope to give patients who may feel disenfranchised by their conditions a voice by encouraging them to discuss their experiences and share their priorities for future research. This is a necessary component to building the Network and represents a new way of conducting research on mood disorders. MoodNetwork is only as strong as its numbers. We have learned that stigma has greatly contributed to slower recruitment and thus, has stalled this innovation in research. By engaging a large and diverse group of participants at MoodNetwork, we hope to further understand the issue of stigma and how to reduce it through systematic investigation and comparative effectiveness research.

Footnotes

Supported by Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Grant PPRN-1306-04925.

L.G.S.: has served in the past year as a consultant for United Biosource Corporation, Clintara, Bracket, and Clinical Trials Network and Institute; and receives royalties from New Harbinger. She has received grant/research support from NIMH, PCORI, AFSP, and Takeda. T.D.’s research has been funded by NIH, NIMH, NARSAD, TSA, IOCDF, Tufts University, DBDAT, Cogito Corporation, Sunovion, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Harvard Medical School. He has received honoraria, consultation fees and/or royalties from the MGH Psychiatry Academy, Brain Cells Inc., Clintara, LLC., Systems Research and Applications Corporation, Boston University, the Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research, the National Association of Social Workers Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Medical Society, Tufts University, NIDA, NIMH, Oxford University Press, Guilford Press, and Rutledge. He has also participated in research funded by DARPA, NIH, NIMH, NIA, AHRQ, PCORI, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, The Forest Research Institute, Shire Development Inc., Medtronic, Cyberonics, Northstar, and Takeda. A.A.N.: is a consultant for the Abbott Laboratories, Alkermes, American Psychiatric Association, Appliance Computing Inc. (Mindsite), Basliea, Brain Cells Inc., Brandeis University, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clintara, Corcept, Dey Pharmaceuticals, Dainippon Sumitomo (now Sunovion), Eli Lilly and Company, EpiQ, L.P./Mylan Inc., Forest, Genaissance, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman LaRoche, Infomedic, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medavante, Merck, Methylation Sciences, Naurex, NeuroRx, Novartis, Otsuka, PamLabs, Parexel, Pfizer, PGx Health, Ridge Diagnostics Shire, Schering-Plough, Somerset, Sunovion, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Targacept, and Teva; consulted through the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute (CTNI) for Astra Zeneca, Brain Cells Inc., Dianippon Sumitomo/Sepracor, Johnson and Johnson, Labopharm, Merck, Methylation Science, Novartis, PGx Health, Shire, Schering-Plough, Targacept and Takeda/Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals. He receives grant/research support from American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, AHRQ, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cederroth, Cephalon, Cyberonics, Elan, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Lichtwer Pharma, Marriott Foundation, Mylan, NIMH, PamLabs, PCORI, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Stanley Foundation, Takeda, and Wyeth-Ayerst. Honoraria include Belvoir Publishing, University of Texas Southwestern Dallas, Brandeis University, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Hillside Hospital, American Drug Utilization Review, American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology, Baystate Medical Center, Columbia University, CRICO, Dartmouth Medical School, Health New England, Harold Grinspoon Charitable Foundation, IMEDEX, Israel Society for Biological Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University, MJ Consulting, New York State, Medscape, MBL Publishing, MGH Psychiatry Academy, National Association of Continuing Education, Physicians Postgraduate Press, SUNY Buffalo, University of Wisconsin, University of Pisa, University of Michigan, University of Miami, University of Wisconsin at Madison, World Congress of Brain Behavior and Emotion, APSARD, ISBD, SciMed, Slack Publishing and Wolters Klower Publishing ASCP, NCDEU, Rush Medical College, Yale University School of Medicine, NNDC, Nova Southeastern University, NAMI, Institute of Medicine, CME Institute, ISCTM. He was currently or formerly on the advisory boards of Appliance Computing Inc., Brain Cells Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Johnson and Johnson, Takeda/Lundbeck, Targacept, and InfoMedic. He owns stock options in Appliance Computing Inc., Brain Cells Inc., and Medavante; has copyrights to the Clinical Positive Affect Scale and the MGH Structured Clinical Interview for the Montgomery Asberg Depression Scale exclusively licensed to the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute (CTNI). The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglun P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dilsaver SC. An estimate of the minimum economic burden of bipolar I and II disorders in the United States: 2009. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Insel TR. Assessing the economic costs of serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:663–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, et al. Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:703–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy JM, Burke JD, Jr, Monson RR, et al. Mortality associated with depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon W. Premature mortality from general medical illnesses among persons with bipolar disorder: a review. Psych Serv. 2015;60:147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rush JA, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR* D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleurence R, Selby JV, Odom-Walker K, et al. How the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is engaging patients and others in shaping its research agenda. Health Aff. 2013;32:393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ, Nierenberg AA, et al. Can phase III trial results of antidepressant medications be generalized to clinical practice? A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet. 2009;374:86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tinetti ME, Studenski SA. Comparative effectiveness research and patients with multiple chronic conditions. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2478–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akincigil A, Olfson M, Siegel M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in depression care in community-dwelling elderly in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alegría M, Chatterji P, Wells K, et al. Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Psych Serv. 2015;59:1264–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:616–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, et al. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roeloffs C, Sherbourne C, Unützer J, et al. Stigma and depression among primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]